This publication of a special issue of the American Journal of Public Health, which focuses on suicide in veterans and service members, is occurring when America has been at war for over a decade. Over this time, suicide in veterans and service members has become a national concern. This can be documented in a number of ways. For one, a search of the Medline database for articles indexed under the expanded subject heading “suicide” and the text words “veteran” or “veterans” identified one article in the year 2000 and three in 2001, but 23 in 2009 and 33 in 2010. For another, a search of the New York Times archives for “veteran” and “suicide” followed by review of the citations identified three articles referring to suicide among American veterans in 2000 and one in 2001, but 11 in 2009 and 15 in 2010. Perhaps most significantly, the 2001 US National Strategy for Suicide Prevention1 did not address suicide in military and veteran populations. However, the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, the public–private partnership charged with revising the strategy, was structured to ensure relevant input. The partnership's public sector cochair is the Secretary of the Army; it includes representatives of the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and relevant support groups on its Executive Committee; and it has formed a work group on military and veterans issues.

There are a series of possible reasons for the recognition of suicide in military and veteran populations as a national priority. As Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF), the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, have gone on, suicide rates have increased in active duty service members, including those who have recently returned from deployment. The American public has responded, in part, to support the troops, and, in part, to ensure that America recognizes the full measure of the costs of war. A number of stories of individual suicides have been widely reported; each one speaks for itself, demonstrating the tragedy and suffering associated with each death. Specifically for VA, there have been a substantial number of reports of problems with mental health services and calls for improvement. There have also been reports recognizing the innovative nature of the VA's programs for suicide prevention. One summary of recent activities2 stated, “In the past few years the Department of Veterans Affairs has become one of the most vibrant forces in the US suicide prevention movement, implementing multiple levels of innovative and state of the art interventions, backed up by a robust evaluation and research capacity.” Anticipating the formation of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention and the revision of the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, the same document included the recommendation to: “Evaluate and assess practices being implemented in the VA for dissemination to the broader healthcare delivery system.1,2

The VA's current suicide prevention program began with the approval of its Mental Health Strategic Plan by the Under Secretary for Health in 2004. The plan was motivated by the recommendations of the 2003 release of the report of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health,3 and by early recognition of the mental health problems facing veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. It included 242 actions that could be factored into 6 domains, including increasing access and capacity, integrating mental health with primary care, transforming mental health specialty care into recovery-oriented services, and implementing evidence-based practices, as well as prioritizing services for returning veterans and suicide prevention. To promote the implementation of the strategy, VA established the Mental Health Initiative as a way to complement its usual mechanisms for funding clinical services with targeted funding for mental health enhancements. This led to an increase in core mental health staff on a national level by 50%, from about 14 000 in 2005 to 21 000 by the end of 2010; approximately half of the increase occurred between 2005 and the end of 2008, and half since then. Moreover, as a means for translating a time-limited strategic plan into the sustained operation of enhanced programs, the strategy led to approval of the Handbook on Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics,4 a policy document that specifies requirements for those services that must be available to all veterans with mental health conditions, and those that must be provided at each medical center and at very large, large, mid-sized, and small community-based outpatient clinics.

Implementation of VA's suicide prevention program was based on the principle that prevention requires ready access to high quality mental health services within the health care system, supplemented by two additional components; first, public education and awareness promoting engagement for those who need help, and second, availability of specific services addressing the needs of those at high risk. Implementation began approximately one year after the Mental Health Initiative was established, after enhancements in access and capacity for the mental health system were already moving ahead. Establishing the program included creating a national office for suicide prevention, partnering with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and its Lifeline to add a centrally located veterans’ call center to the national 800–273-TALK crisis line and funding suicide prevention coordinators with support staff in each VA medical center and in the largest of the outpatient clinics. The crisis line has been the focus for public information campaigns that promoted use of the crisis line for veterans. Thus, it serves as a tangible symbol for the availability of VA as a source for care as well as a component of VA services. Responders in the VA crisis center can access medical records of those seeking help, and they can refer them to the suicide prevention coordinator at the closest VA medical center. The suicide prevention coordinators at each facility receive referrals from the crisis line, facilitate coordination and care of suicidal patients within the facility, and conduct outreach to providers and stakeholders in the community. Thus, VA's program includes two types of hub and spoke networks to help veterans engage in care. The national system includes the crisis center as a hub and the suicide prevention coordinators as spokes. The local systems include the suicide prevention coordinators as hubs and both VA and community providers as spokes.

Other actions included policy requirements for screening all VA patients for mental health conditions at least annually, with follow-up evaluations of the risk for suicide in those who screen positive; for identifying veterans at high risk for suicide and for ensuring that they receive enhanced care; and for using safety planning5 as an intervention for those at high risk. Additional components of the system included two centers for research, education, and clinical innovation, and extensive evaluation activities within the office of suicide prevention and in the mental health program. Parts of the system that are still evolving include collaborations with the DoD; extensions of the crisis line to include Internet chat and texting services, a self-assessment component on the Internet, and systems for surveillance for suicide attempts.

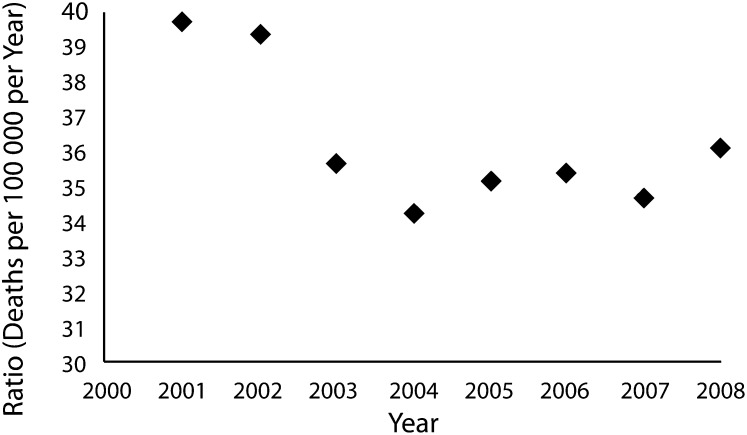

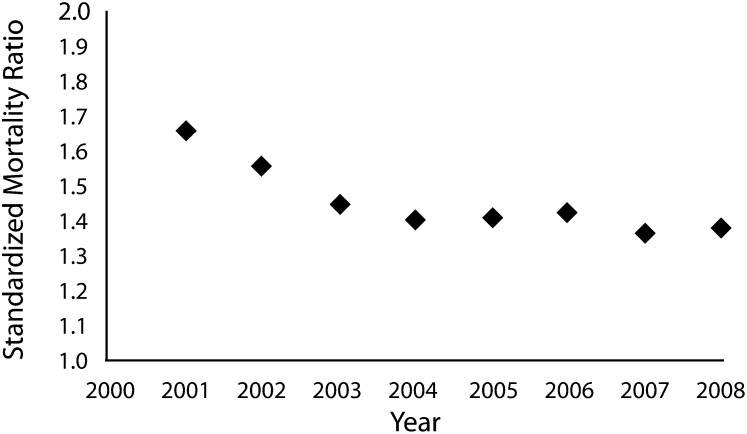

It is important to evaluate the impact on veterans of all that has happened since the start of OEF/OIF. At this time, there are no definitive national listings of veterans across eras of service, and it is not possible to determine the annual count or rate for deaths from suicide among the entire veteran population. However, data are available for veterans who have utilized clinical services in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the VA's health care system (see McCarthy et al.6 for methods). For veterans utilizing VHA services, rates and standardized mortality ratios (rates relative to age- and gender-matched people from the US population) decreased from fiscal year 2001, before the start of the war in Afghanistan, to 2008, the most recent year for which data were available as of the end of fiscal year 2011 (Figures 1 and 2). During this time, the number of veterans served per year increased from approximately 4.0 million to 5.3 million, and the number of suicides increased from 1609 to 1909. The suicide rate decreased by 9%, and the standard mortality ratio by 14%. The decrease appeared to begin in 2002 or 2003, before the VA Mental Health Strategic Plan, the Mental Health Initiative, and the implementation of VA's current program for suicide prevention. Rates and standard mortality ratios remained more or less constant since 2003, during a period of intense improvements in mental health and suicide prevention activities.

FIGURE 1—

Suicide rates for veterans using Veterans Affairs (VA) health care relative to other age- and gender-matched Americans: 2001–2008.

FIGURE 2—

Standardized mortality ratios for veterans using VA health care relative to other age- and gender-matched Americans: 2001–2008.

What events in 2002 or 2003 could explain the decrease in suicide rates in VHA? It is possible to develop two hypotheses, one related to specific legislation and the other to a “yellow ribbon” effect related to increases in community support. The Veterans Millennium Health Care Act (Public Law 106–117), enacted in 1999 and implemented over subsequent years, provided for increases in VHA services, including mental health services and other benefits. However, the increases were modest relative to subsequent enhancements. Moreover, the need for the Mental Health Strategic Plan and subsequent enhancements were apparent to VA leadership through evaluations of the system after the act was implemented. Therefore, the yellow ribbon hypothesis appears to be more likely. According to this hypothesis, the decrease in suicide rates that began in 2002 or 2003 could be attributed to the start of the war, the way that it changed the public's view of military service and of veterans, and, probably, the way it led to changes in veterans’ perceptions of the way America valued their history of service. Conceptually, this hypothesis is supported by models in which strengthening the sense of belonging to a valued community or group can protect against suicide.7 Empirically, it is supported by observations that perceived social support (including community support) is associated with decreased suicidal ideation in National Guard Members returning from OEF/OIF.8

The yellow ribbon hypothesis suggests a number of secondary questions: do the increased rates of suicide in active duty personnel reflect the sum of opposing effects, a direct effect that is increasing rates, and an indirect effect mediated through increased support that is decreasing rates? Have the hypothesized yellow ribbon effects been persistent, or were they responsible for the initiation of a decline in suicide that has been sustained through other factors, such as clinical programs? What will happen at the end of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq if there are decreases in public support for service members and veterans?

Regardless of the reasons for the decline in suicide rates, the substantial changes that occurred before the implementation of VA's mental health enhancements and its suicide prevention program complicate VA's evaluations of these programs. VA is continuing to follow rates as data from additional years become available. It is also pursuing other strategies, including evaluations of specific subpopulations and studies of the associations between regional variability in program implementation and outcomes. At the same time, it continues to enhance its suicide prevention activities.

Assuming for moment that the yellow ribbon hypothesis is valid, there may be important lessons to be drawn from the observed decrease in suicide rates. First, it may be important to reframe the discussion of the war-related increases in national concerns about the health and well-being of service members and veterans as previously summarized. In a sense, the increase in national concerns about service members and veterans may have constituted an intervention. In this context, supporting our troops and our veterans is not only a matter of patriotism; it is a matter of public health. Second, the magnitude of the yellow ribbon effects observed in veterans appears to be at least as great as the effects of large-scale and broad-based interventions in an integrated health care system. Therefore, observation from the VA during a unique era in our nation's history may provide support for the importance of public health models for suicide prevention. Key questions that remain are about how the yellow ribbon hypothesis can be tested, and, if validated, how the findings can be translated into generalizable public health interventions.

Acknowledgments

Analyses of suicide rates and standard mortality ratios were conducted by the VA Serious Mental Illness Treatment Resource and Evaluation Center, Ann Arbor, MI.

Note. I. Katz is an employee of the Department of Veterans Affairs The opinions expressed in this editorial are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect policies or positions of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and objectives for action. Public Health Service. Publication ID SMA01-3517, 2001. Available at: http://www.SAMHSA.gov/prevention/suicide.aspx. Accessed January 3, 2012.

- 2.Suicide Prevention Resource Center and Suicide Prevention Action Network USA. Charting the Future of Suicide Prevention: A 2010 Progress Review of the National Strategy and Recommendations for the Decade Ahead. Available at: http://library.sprc.org. Accessed January 3, 2012.

- 3.President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Final Report to the President. 2003. Publication ID SMA03–3832. Available at: http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/mentalhealthcommission/reports/reports.htm. Accessed January 3, 2012.

- 4.Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration. Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics. Handbook 1160.01. 2008. Available at: http://www.va.gov/vhapublications/index.cfm. Accessed January 3, 2012.

- 5.Department of Veterans Affairs. SPRC Best Practices Registry: Section III. Adherence to Standards. Safety Plan Treatment Manual to Reduce Suicide Risk. Veterans: Veteran Version. 2011. Available at: http://www2.sprc.org/sites/sprc.org/files/SafetyPlan.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2012.

- 6.McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Kim HM, Ilgen M, Zivin K, Blow FC. Suicide mortality among patients receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration health system. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1033–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:575–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pietrzak RH, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Johnson DC, Southwick SM. Risk and protective factors associated with suicideal ideation in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:102–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]