Abstract

The US National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (National Strategy) described 11 goals across multiple areas, including suicide surveillance. Consistent with these goals, the Department of Defense (DoD) has engaged aggressively in the area of suicide surveillance.

The DoD's population-based surveillance system, the DoD Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) collects information on suicides and suicide attempts for all branches of the military. Data collected includes suicide event details, treatment history, military and psychosocial history, and psychosocial stressors at the time of the event.

Lessons learned from the DoDSER program are shared to assist other public health professionals working to address the National Strategy objectives.

THE US NATIONAL STRATEGY for Suicide Prevention1 (National Strategy) provided a framework for action in the United States. This “roadmap” directed a coordinated approach to suicide prevention for both public and private sectors that has guided efforts to modify attitudes, policies, and services. The National Strategy was published in 2001 and included 11 goals in areas that range from developing broad-based support for suicide prevention to improving entertainment and news media portrayals of suicidal behavior. Goal 11 was “Improve and Expand Surveillance Systems” and was the focus of this article.

Since the release of the National Strategy, the military has experienced a rising suicide rate,2 and Department of Defense (DoD) leaders have dedicated significant effort toward improving all areas of the suicide prevention mission, including surveillance approaches.3 The DoD surveillance program provides an example of one approach to addressing surveillance challenges related to suicide. The purpose of this article was to review the DoD's suicide surveillance program, the DoD Suicide Event Report (DoDSER), and suggest how this effort can inform broader public health initiatives seeking to address some of the surveillance concerns detailed in the National Strategy.

DOD SUICIDE EVENT REPORT

Historically, the military services (Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps) collected suicide surveillance data through separate systems. Each system had its own strengths and limitations. Aggregated DoD-level analyses were not possible because the same data points were not collected with standardized items. In addition, it was not possible to compare the services’ data.

The DoD identified a standardized suicide surveillance system as a key goal. In the first phase of development, a collaborative plan was developed to synchronize surveillance efforts across services while also seeking to maintain flexibility to address service-specific needs. The general requirements included a web-based data management application, analytic reporting features, and standardized data collection items. The data collection process was developed to build on processes the services had used previously. The Army's surveillance software was optimized to meet the needs for the DoDSER application. Barriers and facilitators of success are described in the section on “Lessons for Other Public Health Initiatives.”

Data Collection

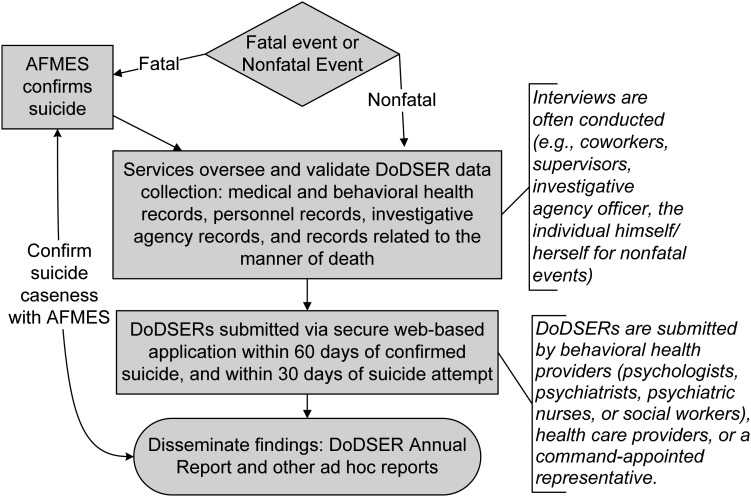

The ultimate objective of the DoDSER program is to provide data that can help refine suicide prevention approaches and ultimately prevent suicides. To accomplish this, the military services ask designated professionals to collect standardized records after suicides and other suicide behaviors, review the records for information related to the DoDSER items, and submit the information via the secure online web application (Figure 1). DoDSERs are submitted for suicides as determined by the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System, and for suicide attempts that result in a hospitalization or evacuation from a combat theater; suicide attempts are defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Self Directed Violence Classification System. Data collected includes detailed demographics, suicide event details, treatment history, military and psychosocial history, and information about other potential risk factors, such as psychosocial stressors at the time of the event. The comprehensive nature of the DoDSER can be seen in the summary of the DoDSER items in Table 1. The items are reviewed annually in collaboration with the services and updated on January 1 of each year. Additional details about the development and implementation of the DoDSER system and data collection process have been reported elsewhere.4

FIGURE 1—

Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) process flowchart.

Note. AFMES = Armed Forces Medical Examiner System.

The following section reviews the National Strategy's assessment of the status of suicide surveillance in the United States. We then describe some of the National Strategy surveillance objectives and how the DoDSER program attempts to address some of the concerns for the DoD.

SUICIDE SURVEILLANCE CHALLENGES AND OBJECTIVES IN THE NATIONAL STRATEGY

The National Strategy defined surveillance as “the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis and interpretation of health data with timely dissemination of findings.”1(p204) Quality surveillance data can be used to “track trends in rates, to identify new problems, to provide evidence to support activities and initiatives, to identify risk and protective factors, to target high risk populations for interventions, and to assess the impact of prevention efforts.”1(p117)

The National Strategy provided a brief review of the status of suicide surveillance at the time of its writing and noted numerous concerns. For instance, there were significant limitations noted for the use of death certificates for surveillance purposes. Death certificates had misclassifications of deaths and suicides, a limited amount of information included, and missing information. Suicide prevention efforts would be improved by the availability of more comprehensive and systematically collected information.

Problems associated with existing sources of information on suicide attempts (e.g., trauma registries and uniform hospital discharge datasets) were also documented. Most of the problems with these data sources resulted from the fact that they were designed for other purposes. Therefore, the resulting data had problems, such as incomplete case capture or incomplete information about the circumstances surrounding the suicide attempt. In addition, systems utilized different definitions for a “suicide attempt” and other self-harm behaviors, therefore creating problems with standardization, comparison, and synthesis of data.

Based on these problems, several objectives were set related to suicide surveillance. The following section provides an overview of the objectives and how DoDSER addressed some of the concerns for the DoD.

National Strategy Objectives and the DoDSER

Enhance the quality and quantity of data available.

Overall, the surveillance goals were “designed to enhance the quality and quantity of data available at the national, state, and local levels on suicide and attempted suicide and ensure that the data are useful for prevention purposes.”1(p120) To that end, the National Strategy aimed to increase the routine collection of information for follow-back studies on suicides. Follow-back studies include data such as information about the decedent, event details, and antecedents of the suicide, which are collected from several sources, such as a review of records and personal interviews. To address the need for more comprehensive suicide data, the National Strategy promoted the development of a national reporting system that would supplement death certificate data with other sources of information, such as medical examiner and law enforcement records.

The DoDSER system was developed to improve the quality and quantity of data available for the DoD. As described previously, the DoDSER collects comprehensive information, including event details and antecedents from a variety of records and personal interviews. In response to the challenge to provide useful data for both national and local needs, the DoDSER software was developed to provide user-defined reports. Individuals with local or “national” (service or DoD-wide) responsibilities can select DoDSER variables of interest and generate numeric and graphical outputs to support suicide prevention needs related to their region of responsibility.

Increase the number of hospitals that collect information about self-harm behaviors.

The National Strategy noted that hospital data on suicide behaviors could provide an extremely valuable tool for suicide research and surveillance. The National Strategy focused on the use of external cause of injury codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision5 (ICD-10), as a mechanism to obtain additional hospital data on suicides and self-inflicted injuries.

The DoDSER system was launched in 2008 and initially required data collection for only suicides. In 2010, however, the requirement expanded to include suicide attempts that “require hospitalization or evacuation from the wartime theater.”6 Some services exceeded this standard and collected DoDSER data on other self-harm behaviors. Typically, the individual collecting the data coordinates closely with (or works on) an inpatient psychiatric ward. All of the applicable items described in the box on this page are collected for suicide attempts consistent with the National Strategy's intent of expanding surveillance capabilities for suicide attempts requiring hospitalization.

List of variables included in the 2010 DoDSER

| Event Information | Planned/premeditated | Had orders to deploy |

| Event type | Observed and intervened | Suicide event related to |

| Suicide (suicide, suicide attempt, self harm, suicidal ideation) | Suicide note | deployment |

| Communicated self harm | Describe additional relevant info | |

| Event date | Primary motivation for suicidal | |

| Event time | behavior for suicide behavior | Personal History |

| Duty environment /status | Victim of | |

| Patient Information | Sequence of events | Physical abuse or assault |

| Name | Sexual abuse or assault | |

| Social security number | Medical History | Emotional abuse or assault |

| Date of birth | Seen in medical treatment | Sexual harassment |

| Sex | facility | Perpetrator of |

| Racial category | Utilized substance abuse | Physical abuse or assault |

| Specific ethnic group | services | Sexual abuse or assault |

| Current marital status | Utilized family advocacy | Emotional abuse or assault |

| Education | program | Sexual harassment |

| Religious preference | Utilized chaplain services | Life Stressors |

| Residence | Utilized outpatient behavioral | Childhood/developmental |

| Resided alone | health Utilized inpatient | history |

| Have minor children | behavioral health | History of |

| Involved in community support | History of traumatic brain injury | Failed intimate relationship |

| List psychiatric diagnoses | Failed relationship other | |

| Military Information | List psychotropic medications | Spousal suicide |

| Component/Military status | Prior self injurious events | Family suicide |

| Primary job code | Received suicide prevention | Suicide by friend |

| Working in primary job code | trainings | Death of spouse or family |

| Duty status | Elaborate on treatment history | member |

| Pay grade | Death of friend | |

| Permanent duty station | Military History | Physical health problem |

| Permanent duty assignment | Court martial proceedings | Chronic spousal or family |

| Unit identification code | Article 15 | severe illness |

| Date of entry into the military | Administrative separation | Excessive debt or bankruptcy |

| Date of rank | proceedings | Job problems |

| Assigned to warrior transition | AWOL/Unexcused absence | Supervisor or coworker issues |

| unit | Medical evaluation board | Poor work performance review |

| Length of time in unit | Civil legal problems | or evaluation |

| Geographic location of event | Non-selection for advanced | Unit or workplace hazing |

| Setting | schooling, promotion, or | Family history of mental illness |

| command | Gun in home or immediate | |

| Event Information | Elaborate on life stressors | environment |

| Hospitalization (inpatient outpatient mental health evaluation/treatment evacuation) | Elaborate on additional details | |

| Deployment History | ||

| How many deployments | Provider Information | |

| Primary method used | Deployment location (most recent last 3) | Respondent's qualifications and contact information |

| Alcohol used during the event | Start dates | |

| Drugs used during the event | End dates | |

| Intended to die | Rest & Recuperation Dates | |

| Self-inflicted injuries | Obtained a waiver to deploy | |

| Death-risk gambling | Experienced direct combat |

Increase the use of annual reports on suicide and suicide attempts.

The National Strategy aimed to increase the number of states that produced an annual report that described the magnitude of the problem. It argued that annual reports would help track trends, identify new problems, and prioritize prevention refinements.

The DoD's National Center for Telehealth and Technology (T2) led the effort to develop the DoDSER program and is required to produce a comprehensive annual report.6 At the time of this writing, three annual reports have been completed and released publically as a resource for the public health community (available at http://www.t2health.org).

Increase knowledge about suicide behaviors in the population.

Obtaining population-based estimates of even the basic frequency of suicide attempts is extremely challenging. The National Strategy sought to increase the number of nationally representative surveys that include items about suicide behaviors to help fill this gap.

The DoDSER program has not attempted to conduct a national survey, but a small proof-of-concept study to collect DoDSER control data, including history of previous self-harm behaviors, was conducted. In the initial phase, soldiers were randomly selected from a large Army installation to conduct a DoDSER interview and provide permission to review their records. The business process was refined, and a second iteration was initiated at the time of this writing. Successful collection of DoDSER control data would provide an extremely valuable resource for analyzing suicide risk factors.

Conduct pilot projects that link data from separate systems.

Linking datasets from separate surveillance systems can increase valuable analytic options exponentially. The National Strategy acknowledged the administrative and privacy barriers posed by this objective and also recommended potential solutions, such as probabilistic matching procedures.

The DoDSER is similar to the CDC National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). Both systems use some similar data sources and seek to provide more comprehensive information about suicides than is typically contained in death certificates. The NVDRS eventually hopes to provide national representation, and it is now operational in 18 states. T2 is currently collaborating with the CDC to conduct probabilistic matching studies of the DoDSER and NVDRS data to examine how the systems may inform one another. Early results support the value of such approaches.

LESSONS FOR OTHER PUBLIC HEALTH INITIATIVES

Internal and external reviews of the DoDSER program identified a number of strengths and growth opportunities. In its short history since 2008, the program has undergone systematic reviews by the Congressionally mandated DoD Suicide Prevention Task Force,3 the RAND Corporation review of the DoD's suicide prevention program,7 and others. In general, these reports praised the DoDSER program as an important advancement in the DoD, and all offered helpful recommendations. The DoDSER system has undergone continuous quality improvement based on these reviews and other DoD experiences with the system. The following section describes some of the primary lessons learned. This information is intended to assist other public health professionals seeking to implement surveillance programs that are consistent with the National Strategy.

Collaborative Partnerships Are Key to the Implementation Phase

Implementation of a new population-based surveillance program is daunting. Challenges range from resourcing, to privacy requirements, to policy needs. Numerous stakeholders and complex business processes must be addressed appropriately. The success of the implementation phase of the DoDSER program was due in large part to a unique collaborative team that shared a vision for what was needed. Each of the services’ suicide prevention program managers played a key role in consensus decisions that focused on the primary needs of the services while demonstrating flexibility on secondary issues. Assistance was provided by the corresponding privacy office and by DoD policymakers and leadership. Significant concerns by any one of a number of groups could have hindered or halted the development of the DoDSER program. Building consensus among key stakeholders early in the implementation phase is critical to success.

Prioritize Resources for Information Management/Information Technology Requirements

An active population-based surveillance system (e.g., one that does not simply rely on existing administrative data) requires a data collection methodology involving numerous individuals over a huge geographic area. Before the development of the DoDSER, several of the military services attempted surveillance procedures without a software tool. All of these efforts proved very challenging, and some failed. For the DoDSER program, a web application provides a key data collection solution for the worldwide surveillance mission; DoDSERs are submitted from Europe, Iraq, Afghanistan, and other locations around the world. The software also serves as a platform to provide users other resources. The skills required for software development, frequent software refinements, and database management suggests that information management and information technology expertise should not be underestimated.

Standardization of an Active Surveillance System Is Challenging

The most common DoDSER recommendation from the systematic reviews of the DoD's suicide prevention program was to improve standardization. Formal research can often create carefully controlled, standardized data collection procedures, but operational surveillance programs face additional challenges and must make multiple tradeoffs. To help improve standardization, the DoDSER program recently added a multimedia training module to the web application, refined the coding manual, and piloted a standardized nomenclature shared by the DoD, Department of Veterans Affairs, and CDC. Identifying feasible approaches to ensure high quality data must be a top priority for any surveillance program.

Weigh the Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Existing Systems and Personnel

The DoDSER system leverages existing DoD personnel to perform data collection responsibilities. This approach has major advantages. The program is extremely cost effective since the use of dedicated personnel to conduct interviews and analyze records would require a major investment. In addition, the current solution permitted the DoD to launch the program several years ahead of other models that would have required staffing solutions. The disadvantages are primarily associated with the fact that DoDSER data collection is an “extra duty.” Behavioral health providers, for example, sometimes manage heavy case loads and manage multiple priorities. The services’ DoDSER program managers must frequently contact providers to emphasize the importance of timely, accurate data submission. These limitations can be mitigated by requesting feedback from personnel, ensuring the data have local value, and working to obtain and maintain “buy in.” Cooperation can be increased when data collectors know how the data are used, or better yet, can access and use the data themselves.

Plan to Educate Consumers of the Data

As described previously, one of the primary surveillance goals of the National Strategy was to address the need for more comprehensive data. When reporting surveillance data, it is always important to educate those using the data about the limitations and interpretive considerations inherent in the data. In a comprehensive system where some data are highly objective and reliable and other data are more subjective, the challenge is amplified. The DoDSER system represents a reasonable approach to collecting information about a topic that is extremely difficult to study, with a strong emphasis on carefully educating consumers of the data.

Intense Administrative Challenges Are Worth the Effort

The experience with the DoDSER data supports the National Strategy priorities; surveillance data are extremely valuable and the challenges are “worth it.” DoDSER data has been used extensively to try to improve suicide prevention in the DoD. For example, the DoD Suicide Prevention Task Force Report cited DoDSER data to support numerous recommendations that will reshape the suicide prevention programs in the DoD. In addition, the National Institute of Mental Health and the Army are partnering to conduct the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Service Members (Army STARRS), the largest suicide study ever conducted in the military. The DoDSER data are serving as one of their most important datasets for their retrospective study. Furthermore, the DoDSER data are used routinely to support senior leaders’ decisions, as well as the efforts of the services’ Suicide Prevention Programs.

CONCLUSION

The National Strategy's surveillance goal aimed to increase the quality and quantity of suicide surveillance data. The DoD worked rapidly in recent years to launch a surveillance program that was consistent with many of the National Strategy's objectives. The lessons learned from this initiative might be useful to other public health initiatives, as well as to leaders who are reviewing and revising the National Strategy for the future.

Acknowledgments

Many individuals and organizations facilitated the development and implementation of the DoDSER program. We are grateful to the services’ behavioral health providers and Command appointed representatives who collect and verify suicide event data and later complete DoDSERs. We also thank the services’ Suicide Prevention Program Managers (SPPMs) and DoDSER Program Managers who oversee the DoDSER data collection process to ensure data integrity and program compliance. In particular, Major Michael McCarthy (Air Force SPPM), Amy Millikan (Manager, Behavioral and Social Health Outcomes Program), Walter Morales (Army SPPM), John Wills (Army DoDSER Program Manager), Lieutenant Commander Andrew Martin (Marine Corps SPPM), and Lieutenant Commander Bonnie Chavez (Navy SPPM) are integral to DoDSER program success. We are also indebted to Lynne Oetjen-Gerdes and Captain Joyce Cantrell, MD, MPH, of the Mortality Surveillance Division of the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System for their support of the DoDSER program.

References

- 1.National Strategy for Suicide Prevention Goals and Objectives for Action. Center for Mental Health Services (US); Office of the Surgeon General (US). Rockville, MD: US Public Health Service; 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuehn BM. Soldier suicide rates continue to rise: military, scientists work to stem the tide. JAMA. 2009;301(11):1111–1113 doi:10.1001/jama.2009.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Challenge and the Promise: Strengthening the Force, Preventing Suicide and Saving Lives: Final Report of the Department of Defense Task Force on the Prevention of Suicide by Members of the Armed Forces. Available at: http://www.health.mil/dhb/downloads/Suicide%20Prevention%20Task%20Force%20final%20report%208-23-10.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2011

- 4.Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Kinn JTet al. DoD Suicide Event Report: Calendar Year 2009 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology, 1–198. 2010. Available at: http://t2health.org/programs/dodser. Accessed November 27, 2011

- 5.International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Plans), Performing the Duties of the Under Secretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) Memorandum, “Standardized Reporting of Department of Defense Suicides and Department of Defense Suicide Event Report,” October 14, 2009.

- 7.Ramchand R, Acosta J, Burns RM, Jaycox LH, Pernin CG. The War Within: Preventing Suicide in the U.S. Military. Monograph Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]