Abstract

Objectives. We examined the role of sleep disturbance in time to suicide since the last treatment visit among veterans receiving Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services.

Methods. Among 423 veteran suicide decedents from 2 geographic areas, systematic chart reviews were conducted on the 381 (90.1%) who had a VHA visit in the last year of life. Veteran suicides with a documented sleep disturbance (45.4%) were compared with those without sleep disturbance (54.6%) on time to death since their last VHA visit using an accelerated failure time model.

Results. Veterans with sleep disturbance died sooner after their last visit than did those without sleep disturbance, after we adjusted for the presence of mental health or substance use symptoms, age, and region.

Conclusions. Findings indicated that sleep disturbance was associated with time to suicide in this sample of veterans who died by suicide. The findings had implications for using the presence of sleep disturbance to detect near-term risk for suicide and suggested that sleep disturbance might provide an important intervention target for a subgroup of at-risk veterans.

Sleep disturbance is prevalent in and strongly associated with a variety of psychiatric and medical conditions.1,2 Several reviews3–5 and commentaries6–8 have highlighted associations of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Insomnia (difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep) and nightmares are the sleep disturbances most commonly associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors, although some work suggests that sleep disordered breathing and periodic limb movement disorder may also pose risks.9

Until recent years, empirical data were almost entirely based on studies of suicidal ideation and nonlethal suicide attempts, with unclear generalization to suicide deaths (hereafter referred to as “suicide”). There is, however, small but growing empirical literature linking sleep disturbance and suicide from cohort studies and investigations using postmortem case–control designs. A Finnish national cohort study of 21 to 64 year-old adults was linked with Finland’s National Death Registry to analyze the association of nightmares and suicide over a mean follow-up of approximately 14 years.10 In adjusted models, the relative risk (RR) for suicide was 1.57 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.12, 2.19) for occasional nightmares and 2.05 (95% CI = 1.06, 3.97) for frequent nightmares compared with the no nightmares referent group. Adjusted analyses were not conducted. In Japan, a community cohort of adults aged 30 to 79 years were surveyed, with a mean follow-up of approximately 7 years.11 Difficulty maintaining sleep was associated with suicide with an age-adjusted RR of 2.4 (95% CI = 1.3, 4.3) and a fully adjusted RR of 2.1 (95% CI = 1.1, 3.9). A 10-year, multisite, observational cohort of older adults (age ≥ 65 years) in the United States was used to compare suicides to control participants drawn from the larger sample.12 Higher sleep quality scores were found to be protective from suicide with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.72 (95% CI = 0.58, 0.87). A Canadian postmortem case–control investigation compared adults who killed themselves during an episode of major depressive disorder to living patients of comparable age and gender with major depressive disorders.13 In unadjusted models, insomnia symptoms were associated with suicide (OR 2.37; 95% CI = 1.21, 4.66), and this remained a significant finding after adjusting for the presence of other psychopathologies (OR 1.78; 95% CI = 1.22, 2.58). In a US case–control study of adolescent suicide,14 hypersomnia and insomnia distinguished suicides from control participants in unadjusted analyses. In adjusted analyses, insomnia in the past week was associated with suicide at a statistically significant level (OR 5.3; 95% CI = 1.4, 20.4). Although samples, methods, and types of sleep disturbance varied across these studies, the findings consistently indicated an association of sleep disturbances to suicide.

We are aware of no other published empirical studies of sleep disturbance and suicide in a veteran population. VHA is the largest integrated health care system in the United States. Veterans who receive VHA care are at increased risk for suicide compared with the US general population.15 More than 1800 VHA users die by suicide each year, representing at least 5% of suicides in the United States annually. Accordingly, suicide prevention among veterans is both a national and VHA priority.16 Sleep disturbances are prevalent in military returnees from Iraq and Afghanistan with posttraumatic stress disorder17 or with mild traumatic brain injury.18 Moreover, VHA users have high rates of sleep disturbance overall,19 compelling the study of sleep disturbance and suicide in this population.

The purpose of our study was to examine sleep disturbance and suicide in a sample of veterans who used Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services and died by suicide. More specifically, we focused on the impact of sleep disturbance on time to death among veteran suicide decedents by comparing a subgroup of suicide decedents with sleep disturbance to a subgroup without sleep problems. Another analysis of this sample showed that mental disorders predicted time to suicide,20 informing our approach to examine sleep disturbance in time to death in the present study.

METHODS

We collected data from all 423 veterans who died by suicide between fiscal years 2000 and 2006 and who received VHA services in Veterans Integrated Service Network 2 (VISN 2), which is located in upstate New York and north central Pennsylvania (n = 130), or from VISN 11 (n = 293), which is located in central Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and northwest Ohio. Of these 423 veteran suicide decedents, 381 (90.8%) received VHA services during their last year of life. All had complete data on the variables included in the final analysis, although 2 participants were missing data for race/ethnicity.

Procedure

Data for the study were obtained in a 2-step process. First, identification of veterans was carried out by the VISN 11 Serious Mental Illness Training, Research, and Education Center, which created a National Suicide Registry by linking data from the VHA National Patient Care Database and the National Center for Health Statistic’s (NCHS) National Death Index (NDI). The NDI is considered the “gold standard” for mortality assessment information because data are derived from death certificates filed in state vital statistics offices and checked for accuracy by NCHS.21 The registry contains information on all patients identified from the NPCD who used VHA services in fiscal years 2000 to 2007, did not have any record of VHA service use in fiscal year 2008 or 2009, and were subsequently identified to have died by suicide by cross-matching to the NDI using social security number, last name, first name, middle initial, date of birth, race/ethnicity, gender, and state of residence. Previously established procedures were used to identify “true” matches.22 Data for the present study were drawn from this registry for veterans receiving care from VHA in VISN 2 or VSIN 11 from 2000 to 2006.

The second step in obtaining data used the VHA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which contains demographic information and all clinical notes about care provided within the VHA system. Notes can be written in free form or using templates and typically include information about the patient’s presenting problem and the type of care provided. CPRS data provide information about symptoms, stressors, and disorders that may or may not be tied to specific visit encounters or treatment plans.

Chart reviews of CPRS records of each of the identified suicide decedents were conducted at the Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention located at the VA Medical Center in Canandaigua, New York. When demographic data were not available in the expected CPRS data fields (e.g., race/ethnicity), the record was searched for references to such data. A chart review tool developed for a previous study of veterans treated for depression23 was used to systematically assess and extract data on documented symptoms of depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorders, illicit drug use, prescription drug misuse, mania, schizophrenia, and sleep disturbance symptoms in the year before suicide. Symptoms were recorded whether they reached a diagnostic threshold or not, necessitating the use of chart reviews (as opposed to relying merely on aggregate electronic data). Inter-rater agreement on reported variables ranged from substantial to outstanding and are provided in the following; readers may reference Britton et al.20 on this issue for agreement on additional variables not reported here.

For each patient record, we used 2 or more independent coders who, after initial coding, met to compare results and resolve discrepancies to create a consensus record for use in analyses. When a clear consensus could not be reached, the coding decisions were staffed at a weekly consensus conference. Percentage agreement was calculated to assess the inter-rater reliability between independent raters.

Measures

Number of days between last visit and death.

The primary outcome for the study was date of the last visit in CPRS, and date of death from the NDI was used to calculate days between last visit and death, which served as the primary outcome variable.

Sleep disturbance.

Chart reviews identified information on documented sleep complaints. The sleep item assessed the presence of sleep problems in patients’ charts. Coders were instructed to code sleep symptoms if any of a wide variety of sleep problems was noted, including trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, sleeping too much, as well as waking up too early. Patients were also identified as having sleep problems if sleep aids were prescribed or if a sleep diagnosis was documented. In assessments based on sleep medications alone, an inclusive approach was used for the “last year,” whereby sleep symptoms were documented if sleep aids were prescribed at any time during the year. For the last visit codes, a more conservative approach was taken. Namely, when use of prescription sleep medications was accompanied by a notation that the patient was sleeping well or sleep was improved, these were coded as having no sleep symptoms at the last visit. Average percentage agreement between raters for sleep disturbance was 89.3% for last year codes and 86.2% for last visit codes.

Psychiatric symptoms.

Chart reviews assessed documented symptoms whether they reached a diagnostic threshold (e.g., depressive symptoms) as well as diagnoses (e.g., depressive disorder), referred to from here forward simply as symptoms. Average percentage agreement between pairs of raters on symptoms was as follows: depression (95.0% last year, 84.7% last visit), mania (93.7% last year, 96.4% last visit), anxiety (90.5% last year, 89.9% last visit), psychotic symptoms (94.3% last year, 93.4% last visit), alcohol use disorder (87.2% last year, 85.3% last visit), illicit drug use (91.0% last year, 91.6% last visit), and misuse of prescription drugs (85.8% last year, 92.4% last visit). Results of the chart review were dichotomized to create 2 categories, individuals with and without symptoms of mental disorders, which included substance use.

Data Analysis

The comparison of interest was between suicide decedents with sleep disturbance in the year preceding death and those without sleep disturbance. Unadjusted comparisons between these groups were made using the χ2 test. For comparisons with sample sizes less than 5, we used the Fisher exact 2-sided test.

To identify variables that would be entered into the multivariate analysis, we conducted univariate Cox proportional hazard regression models. Variables that were statistically associated with time to death (P < .05) were entered into the multivariate model. Backward elimination was used to trim the model because it avoided the potential biases of forward selection procedures.24,25

Variables that were statistically associated with time to death (P < .05) were kept in the model. Diagnostics revealed that sleep problems violated the proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model. Although treating sleep as a time-varying covariate was an option, we decided to use an accelerated failure time (AFT) model because such models make no proportionality assumption and they model the survival time rather than hazard rate, allowing estimation of the actual time after contact to suicide rather than the chance of instantaneous failure over the follow-up.26 In a cohort where all persons died and the probability of death was 1, the time to event might provide a more informative outcome than would the instantaneous probability of death. To fit the AFT data with a survival distribution most appropriate to the data, we compared several different distributions with the Akaike Information Criterion statistic,27 which identified the log-normal AFT model to be a better fit than the log-logistic, Weibull, and Gompertz models.28 We reran all univariate and multivariate analyses using the log-normal AFT model and only reported these results. As is the practice in reporting results from AFT models, we reported survival time as time ratios with 95% CIs, where values less than 1 represented a decrease in survival time (and values greater than 1 represented a prolonged survival time).26 Median time to event for the referent group (those without sleep disturbance) was calculated from the reverse log of the model intercept coefficient (i.e., exp[coefficient]); median time to event for the sleep disturbance group was exp(intercept coefficient minus absolute value of sleep coefficient). All analyses were conducted with STATA 10 (Stata Corporation: College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Of the 381 suicide decedents analyzed, 173 (45.4%) had clinician-documented sleep disturbance, and 208 (54.6%) had no recorded sleep problems. Age, gender, minority status, and the presence of psychiatric or substance abuse symptoms were associated with sleep problems (Table 1), whereas no such associations were present for VISN or region.

TABLE 1—

Demographics of Veterans Health Administration Suicide Decedents With and Without Sleep Disturbance: VISN 2 and VISN 11, Fiscal Year 2000–2006

| Variables | With Sleep Disturbance, No. (%) | Without Sleep Disturbance, No. (%) | χ2 | P |

| Gender | 6.06 | .03a | ||

| Male | 164 (94.8) | 206 (99.0) | ||

| Female | 9 (5.2) | 2 (1.0) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 5.66 | .02 | ||

| White | 150 (86.7) | 159 (76.4) | ||

| Minority | 23 (13.3) | 47 (22.6) | ||

| Age, y | 25.87 | < .001a | ||

| 18–34 | 3 (1.7) | 8 (3.8) | ||

| 35–54 | 45 (26.0) | 26 (12.5) | ||

| 55–74 | 88 (50.9) | 85 (40.9) | ||

| ≥ 75 | 37 (21.4) | 89 (42.8) | ||

| Region | 0.45 | .5 | ||

| VISN 2 | 51 (29.5) | 68 (32.7) | ||

| VISN 11 | 122 (70.5) | 140 (67.3) | ||

| Diagnosisb | 72.69 | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 157 (90.8) | 104 (50.0) | ||

| No | 16 (9.2) | 104 (50.0) |

Note. VISN = Veterans Integrated Service Network. For veterans with a sleep disturbance, the sample size was n = 173 (45.4%); for veterans without sleep disturbance, the sample size was n = 208 (54.6%).

Calculated via the Fisher exact test.

Diagnosis was the presence of psychiatric or substance abuse symptoms or diagnosis.

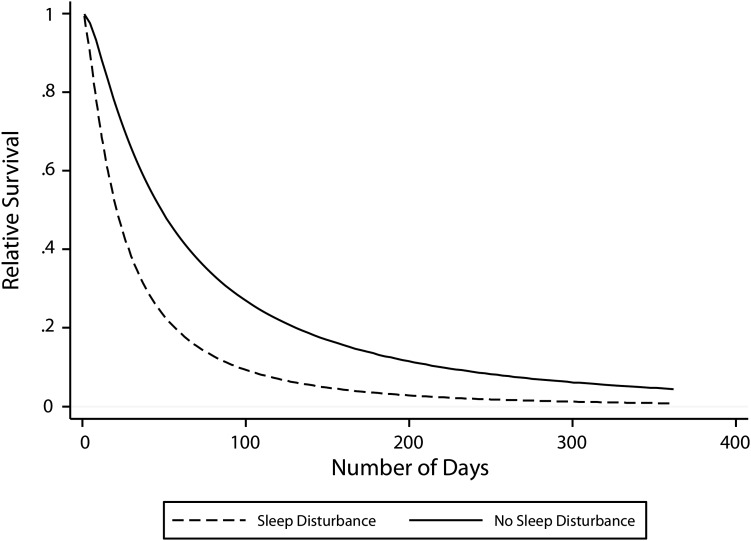

In univariate log-normal AFT analyses, sleep problems, psychiatric or substance abuse symptoms, gender, and VISN or region had significant associations with time to death. Accordingly, these 5 variables were entered into the multivariate analysis (Table 2). Following backward elimination, gender and age did not contribute to the model and were removed. The final model for time to death included sleep disturbance, psychiatric or substance abuse symptoms, and VISN or region. Sleep disturbance predicted a 57% loss in survival time after control for the presence of psychiatric or substance abuse symptoms and region (Table 2). Specifically, the average veteran without sleep problems died 174 days after their last contact with VHA (exp[5.16]), whereas the average veteran with sleep problems died 75 days after their last contact (exp[5.16–0.84]). A survival curve was plotted to illustrate the survival rates for both groups over the follow-up period (Figure 1).

TABLE 2—

Survival Time Ratios for the Log-normal Accelerate Failure Time (AFT) Model for Veteran Suicides With and Without Sleep Disturbance: VISN 2 and VISN 11, Fiscal Year 2000–2006

| Univariate Analyses |

Multivariate Analysis |

|||

| Variable | Coefficient | Survival Time Ratio (95% CI) | Coefficient | Survival Time Ratio (95% CI) |

| Sleep | −1.01 | 0.36 (0.28, 0.47) | −0.84 | 0.43 (0.33, 0.56) |

| Diagnosis | −0.92 | 0.40 (0.30, 0.52) | −0.62 | 0.54 (0.40, 0.71) |

| Age Group | −0.05 | 0.95 (0.80, 1.13) | … | … |

| Gender | 0.89 | 2.45 (1.10, 5.42) | … | … |

| White | −0.30 | 0.74 (0.52, 1.04) | … | … |

| VISN 2 | −0.44 | 0.64 (0.48, 0.86) | −0.45 | 0.64 (0.49, 0.82) |

| Constant | …a | … | 5.16 | … |

Note. CI = confidence interval; VISN = Veterans Integrated Service Network.

The intercept varied depending on the univariate model.

FIGURE 1—

Survival time preceding suicide among veterans with and without sleep disturbance: VISN 2 and VISN 11, Fiscal Year 2000–2006.

Note. VISN = Veterans Integrated Service Network. The dashed line is sleep disturbance in the year preceding death; the solid line represents no sleep disturbance in the year preceding death.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we examined the contribution of sleep disturbance to time to death after the last visit in a sample of veterans in VHA care that died by suicide. The group with recorded sleep disturbance died more quickly after their last visit, after control for the presence of age, region, and symptoms of several mental disorders that conferred risk for suicide, including substance use disorders. The central finding that sleep disturbance predicted shorter time to suicide among suicide decedents provided important information on clinician-observed risk factors for imminent suicide risk and had implications for suicide prevention and treatment efforts.

Although numerous studies examined the heterogeneity among suicide decedents by comparing subgroups of suicides,29–31 this might be the first such undertaking to compare suicide decedents on the basis of sleep disturbance. Given the considerable heterogeneity among individuals who died by suicide,29,30 including among veterans,31 it was suggested that prevention and treatment efforts be tailored to distinct subgroups of vulnerable patients who might require different prevention and intervention strategies.32 Veterans receiving VHA services who present with sleep disturbance, particularly in the face of other suicide risk factors, might represent one such subgroup.

Limitations of the study included data derived from chart reviews, and although coding between raters was done reliably, information about the reliability, validity, or completeness of the information contained in the charts was not available, and it was not possible in this study to control for charting practices of providers. Although a strength of the study was the ability to control for a number of factors, some conditions such as traumatic brain injury and a number of specific mental disorders were not available for analyses. In addition, generalizability to VHA patients in other regions of the country who were not sampled was unclear, as was generalizability to non-VHA samples. The study also did not distinguish among types of sleep disturbance. Finally, unlike studies that assessed sleep disturbance as a risk factor for suicide using a nonsuicide comparison group, in our study, all veterans died by suicide, ruling out inferences about sleep disturbance as a causal risk factor for suicide.

To our knowledge, the present analysis was the first to examine the heterogeneity among suicide decedents using sleep disturbance as the probe and adds to the small but growing literature on sleep disturbance and suicide. Looking forward, there are several reasons to accelerate research on sleep disturbance and suicide. First, because sleep disturbances may also precede depression,33 such disturbances provide an opportunity to begin monitoring early in the development of a recognized risk for suicide. Second, we believe that veterans generally may be more ready to acknowledge sleep disturbances before reporting psychiatric symptoms such as depression or anxiety, although this idea requires empirical study. Third, the strong association between sleep disturbance and time to suicide also indicates a potential entrée for novel preventive interventions. Efficacious and evidence-based approaches for major sleep disorders are available34 and appear to have an impact on reducing psychiatric symptoms that are associated with suicide (e.g., depression and anxiety)35–38; therefore, the mechanisms of action may work through multiple pathways. Research is therefore needed to test the potential of sleep interventions as viable standalone or adjuvant suicide prevention interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), VISN 2 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention.

The authors would like to thank Heather Walters for training the coders, Liam Cerveny, Suzanne Dougherty, Sharon Fell, Elizabeth Schifano, and Patrick Walsh for conducting the chart reviews, and Brady Stephens for creating and managing the database.

Note. VA had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the article; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Human Participant Protection

The study protocol was approved by the Syracuse VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.Pigeon WR. Insomnia as a risk factor for disease. : Buysee DJ, Sateia MJ, Insomnia: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2010: 31–41 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Riedel BW, Bush AJ. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep. 2007;30:213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X, Buysse DJ. Sleep and youth suicidal behavior: a neglected field. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:288–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singareddy RK, Balon R. Sleep and suicide in psychiatric patients. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2001;13:93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernert RA, Joiner TE. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: a review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:735–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agargun MY, Besiroglu L. Sleep and suicidality: do sleep disturbances predict suicide risk? Sleep. 2005;28:1039–1040 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohyama J. More sleep will bring more serotonin and less suicide in Japan. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75(3):340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pigeon WR, Caine ED. Insomnia and the risk for suicide: does sleep medicine have interventions that can make a difference? Sleep Med. 2010;11:816–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakow B, Artar A, Warner TDet al. Sleep disorder, depression, and suicidality in female sexual assault survivors. Crisis. 2000;21:163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanskanen A, Tuomilehto J, Viinamaki H, Vartiainen E, Lehtonen J, Puska P. Nightmares as predictors of suicide. Sleep. 2001;24:844–847 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujino Y, Mizoue T, Tokui N, Yoshimura T. Prospective cohort study of stress, life satisfaction, self-rated health, insomnia, and suicide death in Japan. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Jones MPet al. Risk factors for late-life suicide: a prospective, community-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:398–406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGirr A, Renaud J, Seguin Met al. An examination of DSM-IV depressive symptoms and risk for suicide completion in major depressive disorder: a psychological autopsy study. J Affect Disord. 2007;97:203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:84–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Kim HM, Ilgen M, Zivin K, Blow FC. Suicide mortality among patients receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration Health System. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1033–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blue Ribbon Report Group Report of the blue ribbon work group on suicide prevention in the Veteran population. 2008. Available at: http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/Blue_Ribbon_Report-FINAL_June-30-08.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2011

- 17.Friedman MJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder among military returnees from Afghanistan and Iraq. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:586–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA. Mild traumatic brain injury in US soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:453–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mustafa M, Erokwu N, Ebose I, Strohl K. Sleep problems and the risk for sleep disorders in an outpatient veteran population. Sleep Breath. 2005;9:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Britton PC, Ilgen MA, Valenstein M, Knox K, Claassen CA, Conner KR. Differences between veteran suicides with and without psychiatric symptoms. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 1):S125–S130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, Hynes DM. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:462–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valenstein M, Kim HM, Ganoczy Det al. Higher-risk periods for suicide among VA patients receiving depression treatment: prioritizing suicide prevention efforts. J Affect Disord. 2009;112:50–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauerbrei W, Royston P, Binder H. Selection of important variables and determination of functional from for continuous predictors in multivariate model building. Stat Med. 2007;26:5512–5528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei LJ. The accelerated failure time model: a useful alternative to the Cox regression model in survival anlysis. Stat Med. 1992;11:1871–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretical Approach. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleves MA, Gould WW. An Introduction to Survival Analysis Using Stata. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Herrmann JH, Forbes NT, Caine ED. Relationships of age and axis I diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1001–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rich CL, Fowler RC, Fogarty LA, Young D. San Diego suicide study. 3. Relationships between diagnoses and stressors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:589–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ilgen MA, Conner KR, Valenstein M, Austin K, Blow FC. Violent and nonviolent suicide in veterans with substance-use disorders. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:473–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan KJ, Harrow M. Psychosis and functioning as risk factors for later suicidal activity among schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients: a disease-based interactive model. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29:10–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige Bet al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pigeon WR, Crabtree VM, Scherer MR. The future of behavioral sleep medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:73–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fava M, McCall WV, Krystal Aet al. Eszopiclone co-administered with fluoxetine in patients with insomnia coexisting with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1052–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, Pedro-Salcedo MGS, Kuo TF, Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31:489–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJet al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:928–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulmer C, Bosworth H, Edinger J, Calhoun P, Almirall D. A brief intervention for sleep disturbance in PTSD: pilot study findings. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:206 [Google Scholar]