Abstract

Purpose

To report retinal findings for healthy newborn infants imaged with hand held Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT).

Design

Prospective observational case series.

Methods

Thirty-nine full term newborn infants had dilated retinal examinations by indirect ophthalmoscopy and retinal imaging by handheld SD-OCT, without sedation, at the Duke Birthing Center.

Results

Of the 39 infants imaged, 44% (17/39) were male. Race/ethnicity composition was 56% white, 38% black, 3% Asian, and 3% Hispanic. Median gestational age was 39 weeks (range 36 to 41). Six of the 39 infants (15%) had bilateral subfoveal fluid on SD-OCT not seen by indirect ophthalmoscopy. Eight infants (21%) had retinal hemorrhages noted on dilated retinal examination, 1 of which had subretinal fluid on SD-OCT. Subretinal fluid was noted on follow up examination to have resolved on SD-OCT 1 to 4 months later. Infants with bilateral subretinal fluid had an older gestational age compared to infants without subretinal fluid (median 40.4 vs. 39.1 weeks, respectively, P=0.03) and were more likely to have had mothers with diabetes (2/6 vs. 0/33, respectively, P=0.02). Vaginal versus C-section delivery was not significantly different between the two groups.

Conclusions

Some healthy full term infants have bilateral subfoveal fluid not obvious on dilated retinal examination. This fluid resolves within several months. The visual significance of this finding is unknown, but clinicians should be aware it is common when evaluating newborn infants for retinal pathology using SD-OCT.

Introduction

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) provides reproducible retinal morphology and cross-sectional tissue measurements in vivo in a rapid, non-invasive, non-contact manner.1 Hand-held OCT is well tolerated by children and infants, and is more sensitive than clinical examination in detecting macular pathology. 2, 3

OCT has been used to identify clinically important retinal pathologies in premature infants, including retinoschisis,4–6 foveal hypoplasia,6, 7 intraretinal cysts,6, 8 preretinal neovascularization,5, 9 and retinal detachment.5, 10 Macular holes,11 hemorrhagic retinoschisis,12, 13 vitreoretinal traction and epiretinal membranes11, 12 were identified in Shaken Baby Syndrome using OCT, and in some cases influenced surgical management. Hand-held SD-OCT was also valuable in characterizing foveal hypoplasia in the eyes of infants with ocular and oculocutaneous albinism14, 15 and in neonates with systemic diseases such as liver failure.16 While hand-held SD-OCT may be performed during examination under anesthesia, anesthesia is not necessary to obtain useful images in infants and cooperative children.2

Establishing a normative database of SD-OCT findings in healthy full term newborn infants is an important prerequisite for the proper diagnosis of retinal pathology using SD-OCT in this population. We are not aware of any report on SD-OCT imaging of healthy full term neonates to date (PubMed Mesh search terms: Optical coherence tomography AND Infant). In this study, a cohort of healthy full term infants was examined by hand-held SD-OCT and indirect ophthalmoscopy shortly after birth.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Thirty-nine healthy full term infants were included in a prospective observational study. The study involved dilated retinal examination by indirect ophthalmoscopy and retinal imaging by hand-held SD-OCT, without sedation, at the Duke Birthing Center between August 2010 and October 2010. Infants’ and mothers’ medical records were reviewed for health history, delivery history, pregnancy history, gestational age of the infant at birth based on reconciliation of menstrual and ultrasound dating criteria, birthweight, and maternal age at the time of delivery. Infants were eligible for the study if they were born at 36 weeks gestation or later and did not have known systemic disease. If ocular abnormalities were identified in the original eye examination, parents were offered a repeat examination monthly until the findings resolved.

Procedures

All infants had both eyes dilated by instillation of one drop of cyclomydril (phenylephrine hydrochloride 1% and cyclopentolate 0.2%), or cyclopentolate 0.5% and phenylephrine 2.5% were given to those infants with darkly pigmented irides. Following pupillary dilation, a pediatric ophthalmologist (MTC or SFF) performed a clinical examination including indirect ophthalmoscopy with a 28-Diopter lens and without an eyelid speculum.

A portable hand-held SD-OCT unit (Bioptigen Inc., Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) was used to image both eyes of all subjects following the age-customized method for SD-OCT in infants described by Maldonado et al2, which allows imaging without sedation or a lid speculum. With this approach, multiple series of double-volumetric 800 A-scans × 80 B-scans centered on the optic nerve or fovea, measuring approximately 7 × 7 mm, were captured. Among the first 7 subjects, 2 infants were noted to have the unexpected finding of bilateral subretinal fluid at the foveal center. Because the clinician was aware of the SD-OCT results, diagnosis using indirect ophthalmoscopy during the clinical examination of these 7 subjects was influenced by this knowledge. Starting with subject #8, all infants were examined first with indirect ophthalmoscopy and then with SD-OCT to mask the clinician from the SD-OCT results. A study investigator later graded the images without knowledge of the indirect ophthalmoscopy results. The eyes of 14 infants were identified to have abnormal findings either by SD-OCT or indirect ophthalmoscopy, and these subjects were therefore offered a repeat examination in the clinic approximately 1 month later, including repeat SD-OCT imaging. Those infants with persistent pathology on either the dilated retinal examination or SD-OCT were asked to return monthly until the abnormality resolved. Infants who were examined at 3 months of age or older underwent the preferential-looking test17 for an assessment of visual function, performed by a masked trained orthoptist with age-matched normal ranges based on previous studies18.

Image Processing

SD-OCT images were converted into Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format and qualitatively graded in OSIRIX medical imaging software (OSIRIX Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland) for the presence or absence of each retinal layer and for any pathologic abnormality present. Subretinal fluid was defined as an area of hyporeflectivity between the neurosensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium. A cystoid space was defined as a distinctive area of hyporeflectivity within the neurosensory retina, extending in 3 dimensions and causing associated distortion of retinal layers. The highest quality scan containing the fovea, based on a subjective assessment of resolution and volume, was selected for quantitative analysis for each imaging session from each eye.

To quantify retinal features, the retinal layers were semi-automatically segmented on a single central scan using the MATLAB-based (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) software DOCTRAP19 v10.2 (Duke University). A custom MATLAB script was implemented on the segmentation output to acquire measurements for retinal thickness and dimensions of retinal pathology.

Statistics

Subjects with bilateral subretinal fluid on SD-OCT were compared to subjects without subretinal fluid with respect to antenatal history (maternal diabetes and maternal age), birth outcomes (length of labor and mode of delivery), postnatal characteristics (gestational age at birth calculated from reconciliation of menstrual and ultrasound dating criteria, birthweight, head circumference, APGAR scores, race, and sex), and other retinal parameters by SD-OCT (presence of persistent inner retinal layers, total central foveal thickness, and foveal thickness of the neurosensory retina). Comparison of categorical variables was performed using the Fisher’s Exact test and comparison of continuous variables was performed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. All statistics performed on ocular findings were adjusted for two eyes from each subject using a generalized estimating equations approach. All statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Patient Demographic Characteristics

Of the 39 newborn infants recruited for the study, 17 (43.5%) were male, 22 (56.4%) were white, 15 (38.5%) were black, 1 (2.6%) was Asian, and 1 (2.6%) was Hispanic. One additional Asian male infant was recruited but later withdrawn by his parents prior to completion of the examination. The median gestational age of the infants was 39 weeks (range 36 to 41). All infants were examined within the first 2 days of life. Five infants received follow-up examinations on time (4 infants at 1 month and 1 infant at both 1 and 2 months). An additional 2 infants did not return to the clinic at the requested 1 month follow up and instead came at later dates (1 infant at 2 months only and 1 infant at 4 months only). (Table 1 and Supplemental Table available at AJO.com)

Table 1.

Newborn subjects with subfoveal fluid (n=6): Demographic, prenatal and delivery history, as well as retinal findings (both clinical and by Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography).

| # | Demographics | Systemic Findings | Delivery | Eye | Retinal Findings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | PMA (weeks) |

Birth- weight (grams) |

Race | Maternal | Infant | Type & Events |

Labor length (hrs) |

Clinical Exam |

SDOCT | Follow up of abnormal findings (months) |

||

| 4 | M | 41 | 3825 | W | Gest DM | none | C/S | 11:00 | R | * | SRF | less SRF (1), resolved SRF (2) |

| L | * | SRF | less SRF (1); resolved SRF (2) |

|||||||||

| 7 | F | 40 | 3635 | B | HTN, DM, obesity |

none | C/S | 11:00 | R | * | SRF | resolved SRF (4) |

| L | * | SRF | resolved SRF (4) | |||||||||

| 11 | M | 40 | 3695 | W | none | none | V | 1:27 | R | normal | SRF | lost to follow up |

| L | normal | SRF | lost to follow up | |||||||||

| 15 | M | 41 | 3060 | W | AMA | none | V | 3:00 | R | normal | SRF | resolved SRF (1) |

| L | normal | SRF | resolved SRF (1) | |||||||||

| 17 | M | 40 | 3760 | W | none | none | V | 1:57 | R | RH | SRF | lost to follow up |

| L | RH | SRF | lost to follow up | |||||||||

| 22 | F | 39 | 3315 | W | AMA | none | V | 11:38 | R | normal | SRF | resolved SRF (2) |

| L | normal | SRF | resolved SRF (2) | |||||||||

M=male, F=female, W=white, B=black, Gest DM=gestational diabetes, HTN=hypertension, AMA=advanced maternal age (>34 yo), C/S=C section, V=vaginal, Labor length=time (in hours) from rupture of membranes to complete delivery, R=right eye, L=left eye,

Early in study examiner was not blinded to the SDOCT results during dilated retinal exams, therefore assessment of possible presence of subretinal fluid was not valid. In those cases, retina appeared otherwise normal, RH=retinal hemorrhages, SDOCT=Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography, SRF=subretinal fluid, NA=not applicable.

Subject Prenatal and Delivery History

Twenty-four infants were born by vaginal delivery without vacuum or forceps and 15 were born by Caesarean section (C-section). One infant was born following shoulder dystocia (#12). Two infants were noted to have facial bruising (#24 and #30), and another two infants were noted to have meconium upon delivery (#19 and #32). All infants were otherwise healthy. (Table 1 and Supplemental Table available at AJO.com)

Retinal findings by Indirect Ophthalmoscopy

Fifteen eyes (8/39 infants or 21%) had retinal hemorrhages noted on dilated retinal examination by standard indirect ophthalmoscopy. Hemorrhages were approximately ¼ to ½ disk diameter in size and appeared intraretinal, discreet, and most dense in the temporal arcades; however, two extended to the macula (#26 and #30). All 8 infants (100%) with retinal hemorrhages were born vaginally compared to 39% (12/31) of infants without retinal hemorrhages (P=0.012). Only 1 infant (#17) with ocular retinal hemorrhages on clinical examination also had bilateral subretinal fluid on SD-OCT. (Table 1 and Supplemental Table available at AJO.com)

No infants with bilateral subretinal fluid noted on SD-OCT had recognizable subretinal fluid or abnormal macular clinical findings on dilated ophthalmoscopic examination when the clinician was blinded to the imaging results. Four eyes of 3 additional infants had the equivocal appearance of foveal elevation based on lighter foveal pigmentation and abnormal contour on dilated ophthalmoscopic examination, without foveal abnormality seen on SD-OCT. (Supplemental Table available at AJO.com)

Retinal Imaging at birth by SD-OCT

All 39 infants tolerated SD-OCT imaging well, with adequate foveal images for the identification of subfoveal fluid obtained in all subjects. An additional infant was removed from the study because the parents became nervous during the SD-OCT imaging and decided that they did not wish to proceed. That infant appeared comfortable during imaging, however. The median total central foveal thickness (including subretinal fluid, if present) for all 78 eyes (39 infants) was 85 (range 55 to 303) microns. Six of the 39 infants (15%) had bilateral subfoveal fluid noted on SD-OCT during the initial imaging session (without definitive subretinal fluid seen on clinical dilated retinal examination). (Figure 1) Subretinal fluid was hyporeflective and without intrafluid turbid or hyperreflective material. The overlying outer retina was hyperreflective. Among eyes with subretinal fluid at the initial SD-OCT examination, the median height and width of subretinal fluid was 28 microns (range 6 – 143) and 651 microns (range 421 – 1907), respectively. The median total central foveal thickness (including subretinal fluid) was 109 microns (range 62 – 303) for eyes of infants with bilateral subretinal fluid vs. 82.5 microns (range 55 – 293) for eyes of infants without bilateral subretinal fluid (P=0.056). Median thickness of the neurosensory retina (measured from the inner retinal border to the outermost edge of the photoreceptor outer segments) at the fovea was 102.5 microns (range 88 – 160) for eyes of infants with bilateral subretinal fluid, and this was significantly greater than that of those eyes without fluid (78 microns, range 55 – 121, P=0.003).

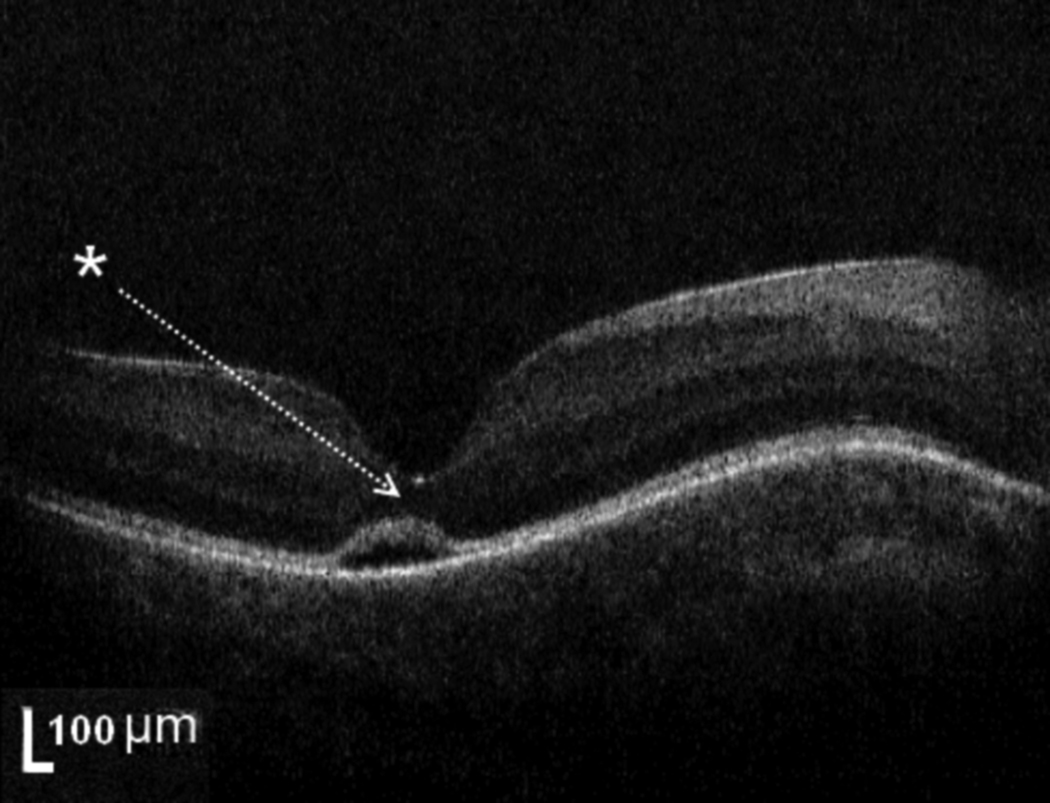

Figure 1. Example of typical SD-OCT from healthy full term newborn infant with subretinal fluid.

This represents a typical amount of subretinal fluid (subject #7, right eye, height 33 microns, median subretinal fluid height 27.5 microns for all 6 infants with fluid). Six of 39 (15%) healthy full term infants imaged with hand-held SD-OCT demonstrate bilateral subretinal fluid at the foveal center. Note the deformation of the photoreceptor layer (white arrow) above the pocket of SRF. In this example, no persistent inner retinal layers are seen at the foveal center. Due to the presence of subretinal fluid, it is difficult to assess the inner segment/outer segment band.

Seventy-two eyes (in 38 subjects) had SD-OCT of sufficient quality for analysis of persistent inner retinal layers at the fovea at the initial examination. Among the 12 eyes (6 infants) with subretinal fluid detected on SD-OCT, 11/12 eyes (5/6 infants, 83%) had SD-OCT of sufficient quality for analysis of the inner retinal layers at the fovea. Of these, 7/11 eyes (4/5 infants, 80%) had persistent inner retinal layers at the fovea on SD-OCT (Figures 1–2). Among the 66 eyes (33 infants) without subretinal fluid detected on SD-OCT, 61/66 eyes (32/33 infants, 97%) had SD-OCT of sufficient quality for analysis of inner retinal layers at the fovea. Of these, 34/61 eyes (19/32 infants, 59%) had persistent inner retinal layers at the fovea on SD-OCT (Figure 3). The proportion of infants with at least 1 eye with persistent inner retinal layers did not significantly differ between the infants with and without bilateral subretinal fluid (80% vs. 59%, respectively, P=0.63).

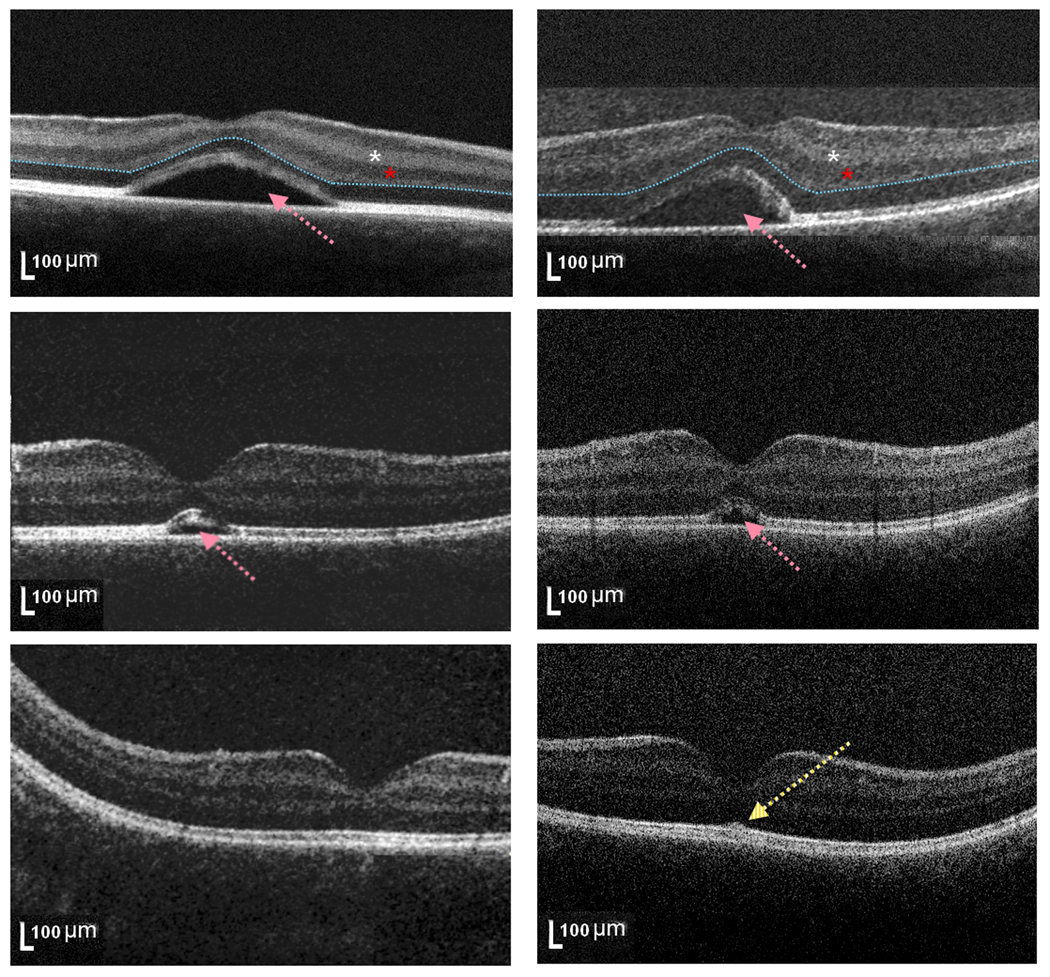

Figure 2. Subretinal fluid reabsorption in healthy full term newborn infant.

SD-OCT scans at the foveal center for the right (left column) and left (right column) eye from subject #4 at birth (top, subretinal fluid height 140 and 143 microns, respectively), 1 month (middle, subretinal fluid height 71 and 55 microns, respectively) and 2 months (bottom, no subretinal fluid appreciated) of age. This subject had an unusually large amount of subretinal fluid (pink arrows). Note a residual slight central elevation of the inner segment/outer segment band at 2 months of age, without subretinal fluid (bottom, yellow arrow). At birth (top), this infant had persistent inner retinal layers (including inner plexiform and inner nuclear layers, white and red asterisk, respectively) at the foveal center, while later scans demonstrated absence of inner retinal layers at the foveal center. The blue dashed line (top) marks the border between inner and outer retinal layers.

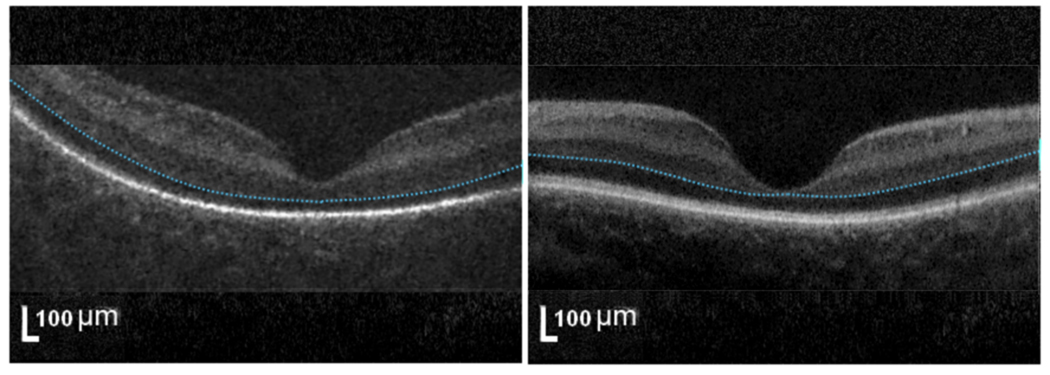

Figure 3. Foveal morphology at birth for healthy full term newborn infants without subretinal fluid.

The eyes of full term newborn infants demonstrated different stages of foveal maturation on SD-OCT. SD-OCT scan at the foveal center from subject #9 (left, underdeveloped) has a well-formed foveal pit but remnants of inner retinal layers (above blue dashed line) while subject #32 (right, developed) has no inner retinal layers at foveal center.

In one case (#20), one irregular intraretinal cystoid structure was noted parafoveally in each eye, measuring 450 microns in width at its widest diameter and 50 microns in height in the inner nuclear layer. This finding was not visualized by indirect ophthalmoscopy; the eyes of this infant demonstrated neither intraretinal hemorrhages on indirect ophthalmoscopy examination nor subretinal fluid on SD-OCT imaging. (Supplemental Table available at AJO.com)

Associated findings in eyes of infants with subretinal fluid

Four of the 6 infants (67%) with bilateral subretinal fluid were born vaginally, while the remaining 2 infants underwent the first stage of labor for 11 hours prior to C-section for failure to progress. Both infants with bilateral subretinal fluid who underwent C-section (#4 and #7) had a history of maternal prenatal diabetes (no infants without bilateral subretinal fluid had a prenatal history of maternal diabetes, P=0.02). Infants with bilateral subretinal fluid had a significantly higher gestational age at birth (based on reconciliation of both menstrual and ultrasound dating criteria) compared to infants without subretinal fluid (median 40.4 vs. 39.1 weeks, respectively, P=0.03). Otherwise, the two groups did not demonstrate statistically significant differences in sex or race distribution, head circumference, APGAR scores, mode of delivery, birthweight, total length of labor, or maternal age. (Tables 1 and 2)

Table 2.

Comparison of non-ocular characteristics of full term newborn infants with vs. without subretinal fluid demonstrated by Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging.

| Factors | Subretinal Fluid (n=6) | No Subretinal Fluid (n=33) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 4 (67%) male | 13 (39%) male | 0.37 |

| Race | 5 (83%) White 1 (17%) Black |

17 (52%) White 14 (42%) Black 1 (3%) Asian 1 (3%) Hispanic |

0.55 |

| Gestational Age | 40.4 (39.4–40.9) weeks | 39.1 (36.1–41.6) weeks | 0.03* |

| Birthweight | 3665 (3060–3825) grams | 3305 (2125–3920) grams | 0.06 |

| Head Circumference | 34.7 (±0.61) cm | 34.11 (±1.32) cm | 0.39 |

| APGAR at 1 minute | 9 (7–9) | 9 (4–9) | 0.84 |

| APGAR at 5 minutes | 9 (range 8–9) | 9 (8–9) | 0.38 |

| Type of Delivery | 4 (67%) vaginal 2 (33%) C-section |

19 (58%) vaginal 14(42%) C-section |

1.00 |

| Total length of Labor | 7.0 (1.5–11.6) hours | 1.9 (0–26.5) hours | 0.13 |

| Maternal Diabetes | 2 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 0.02* |

| Maternal age | 30 (25–40) years | 29 (18–41) years | 0.40 |

P< 0.05, continuous variables are presented as mean (± standard deviation) for normally distributed variables and median (minimum-maximum) for others

Retinal examination of infants with bilateral subretinal fluid at follow-up by SD-OCT and Indirect Ophthalmoscopy

Three infants with bilateral subretinal fluid received a follow up retinal examination and SD-OCT one month later. At that time, 2 infants (#15 and #22) were found to have normal appearing foveas in both eyes while 1 infant (#4) was found to have persistent but diminished subretinal fluid in both eyes compared with the initial exam (fluid height decreased from 140 to 71 microns in the right eye, and from 143 to 55 microns in the left eye; fluid width decreased from 1839 to 544 microns in the right eye, and from 1907 to 621 microns in the left eye). Although the subretinal fluid had completely resolved in both eyes of this infant on additional SD-OCT imaging at 2 months of age, the appearance of the inner segment/outer segment photoreceptor junction was not entirely normal compared to other scans of similarly aged infants without subretinal fluid (Figure 2). A fourth infant (#7) with bilateral subretinal fluid by SD-OCT at birth did not return for a follow up examination until 4 months of age, at which point both eyes showed normal-appearing foveas by SD-OCT and retinal examination; the eyes were aligned and vision was normal by the preferential-looking test (binocular vision 4.7 cycles/degree, normal for age). (Table 1)

Discussion

Six of the 39 healthy full term newborn infants (15%) had the unexpected finding of bilateral subfoveal fluid on SD-OCT 1 to 2 days after delivery. To our knowledge, there have been no published reports of foveal detachments in this population (PubMed Mesh search terms: Optical coherence tomography AND Infant; Retinal Detachment AND Infant, Newborn NOT Retinopathy of Prematurity). Subfoveal fluid has been documented by SD-OCT in the eyes of 2 infants (ages 13 and 24 months, respectively) with shaken baby syndrome; however, multiple additional retinal pathologies were also noted, suggesting a differing mechanism from the cases in the present study.20 Maldonado and colleagues described normal macular SD-OCT findings in the eyes of a single, healthy, full term, 1-month-old newborn infant as well as 3 additional full term infants under 1 year of age.21 The relatively low incidence (15% of infants) and transient nature (resolving within a few months) likely explains why this phenomenon has not been observed in previous SDOCT studies of full term infants.

Parafoveal cystoid structures and epiretinal membranes have been previously documented by SDOCT imaging in premature infants; however, subfoveal fluid was not reported in those patients.8 Another study identified bilateral foveal cystoid structures and unilateral extrafoveal subretinal fluid by SDOCT in a full term infant with hemochromatosis and liver failure.16 The current study had one case of a single parafoveal small cystoid structure bilaterally without subretinal fluid in a full term newborn, unlike the numerous cystoid structures seen in previous studies.

Only 1 of 6 infants with bilateral subretinal fluid by SD-OCT imaging also had retinal hemorrhages on clinical examination, suggesting different causes for these 2 findings. While delivery by C-section appears to have a protective effect on intraretinal hemorrhages in the present and prior studies,22, 23 delivery method (vaginal or C-section) was not associated with the presence of subretinal fluid by SD-OCT in this study (P=1.00). Moreover, the 2 infants with bilateral subretinal fluid who were born by C-section did not undergo the second stage of labor, when passage through the birth canal would have put the infant at similar risks to vaginal delivery.

The cause of subfoveal fluid in the eyes of healthy, full term infants is unknown. There was no evidence of inflammatory or vascular disease, optic pit, or choroidal hemangioma in any of these infants’ eyes. One possible mechanism is central serous retinopathy, a phenomenon which has been noted in women during their 3rd trimester of pregnancy, with resolution within the first few months after delivery.24 Alternatively, bilateral serous retinal detachments have been documented on ophthalmoscopic examination of infants in cases of maternal preeclampsia, and a similar pathogenesis may be occurring here.25 However, these findings were not seen in healthy infants, and there was no evidence of preeclampsia in any mothers in the present study. Finally, this may be a normal variation in healthy infants at birth, unrelated to any maternal or infant pathology.

Could subfoveal fluid be a normal part of retinal development? We do not believe that the subretinal fluid observed in healthy newborns by SD-OCT is an early stage of normal retinal development for several reasons. The infants in this study with bilateral subfoveal fluid on SD-OCT tended to be post dates rather than premature. Furthermore, previous studies reporting the SD-OCT findings of premature infants did not document this phenomenon.4–10, 21 Infants with bilateral subretinal fluid did not significantly differ from infants without bilateral subretinal fluid in the prevalence of persistent inner retinal layers at the foveal center, an important sign of premature retinal development26–28.

The visual consequences of the subfoveal fluid are unknown. All 4 infants who had subsequent retinal examination and SD-OCT imaging demonstrated resolution of subretinal fluid by 1 to 4 months of age. Fifteen percent of healthy newborn babies in this cohort had subretinal fluid in both eyes. Myopia occurs at a similar rate (15% to 22.2%) in adult populations29–34. Other ocular diseases occur at a lower rate in the general population including amblyopia (0.8–3%)30, 35–37 and strabismus (0.8–3.3%)30, 35, 36, 38. Clinically significant visual acuity deficit is therefore an unlikely consequence of transient subfoveal fluid just after birth. In addition, the infant with subretinal fluid and the longest follow up (4 months) in this study had normal ocular alignment and normal vision for age by the preferential-looking test. Follow up studies are needed to determine the visual and refractive outcomes for this population.

The present study has several limitations. Mothers of infants with bilateral subretinal fluid had a higher rate of diabetes than other mothers in this study. However, we are cautious to draw conclusions on fetal and maternal risk factors for subretinal fluid from such a limited sample size. In addition, not all infants with bilateral subretinal fluid received follow up examinations, and clinical assessment of visual function was limited in these young infants. Although clinical retinal examination by indirect ophthalmoscopy failed to detect the subretinal fluid or parafoveal cysts seen on SD-OCT in all cases (once the clinician was appropriately masked to the SD-OCT results), it is possible that these subclinical findings are all destined to resolve without long-standing visual or architectural ramifications for the infant’s retina. On the other hand, hand-held SD-OCT was noninvasive, and infants tolerated the imaging well, demonstrating that this technology is a useful clinical tool for detecting retinal macular abnormalities in the eyes of newborn infants.

The significance of subfoveal fluid in the eyes of healthy newborn infants is unknown, and the fluid appears to resolve by 1 to 2 months of age. Longer follow up would clarify the functional consequences of transient subfoveal fluid, if any. As more clinicians utilize hand-held SD-OCT to evaluate young infants for retinal disease and morphology, they should be aware that subfoveal fluid is a common SD-OCT finding in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements/Disclosure

Funding/Support: Angelica and Euan Baird; The Hartwell Foundation; Grant Number 1UL1 RR024128-01 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. This work is also supported by a grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Toth receives research support through Duke University from Alcon Laboratories, Bioptigen, Genentech, National Institutes of Health, Research to Prevent Blindness; is an advisory board consultant for Alcon Laboratories and Genentech; and receives royalties through Duke University from Alcon and potentially Bioptigen. Duke University has an equity interest in Bioptigen. Drs. Toth and Farsiu have a patent pending on OCT image processing techniques. Dr. Farsiu receives research support through Duke University from Bioptigen. Dr. Freedman is a consultant for Pfizer.

Author contributions: Design of the study (MTC, RSM, RVO, CAT, SSS, GMP, GKS, SFF); conduct of the study (MTC, RSM, RVO, BC, SFF); collection of data (MTC, RSM, BC, SFF); management of data (MTC, RSM, RVO, BC, CAT, SSS); analysis of data (MTC, RSM, CAT, RVO, SJC, SF, DKW, SSS, SFF); interpretation of data (MTC, RSM, CAT, RVO, DKW, GMP, GKS, SSS, SFF); manuscript preparation (MTC, RSM, SFF, CAT); manuscript review and approval (all authors)

Statement about conformity with author information: This study and data accumulation were approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from parents of all participating infants. This study is in accordance with HIPAA regulations.

Other acknowledgements: None.

Biography

Michelle Trager Cabrera, MD

Dr. Cabrera is completing a fellowship in pediatric ophthalmology at the Duke Eye Center. She received a Bachelors degree in Biological Sciences from Stanford University, graduating with honors and joining Phi Beta Kappa. She then completed both medical school and ophthalmology residency at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Cabrera’s research interests have recently focused on pediatric retinal disease. She will be joining the faculty at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental material available at AJO.com

References

- 1.Ho J, Sull AC, Vuong LN, et al. Assessment of artifacts and reproducibility across spectral- and time-domain optical coherence tomography devices. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(10):1960–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maldonado RS, Izatt JA, Sarin N, et al. Optimizing hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging for neonates, infants, and children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(5):2678–2685. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Luo CK, Materin MA, Shields JA. Optical coherence tomography in children: analysis of 44 eyes with intraocular tumors and simulating conditions. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2004;41(6):338–344. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20041101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muni RH, Kohly RP, Charonis AC, Lee TC. Retinoschisis detected with handheld spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in neonates with advanced retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):57–62. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavala SH, Farsiu S, Maldonado R, Wallace DK, Freedman SF, Toth CA. Insights into advanced retinopathy of prematurity using handheld spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(12):2448–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi MM, Trese MT, Capone A., Jr Optical coherence tomography findings in stage 4A retinopathy of prematurity: a theory for visual variability. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(4):657–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lago A, Matieli L, Gomes M, et al. Stratus optical coherence tomography findings in patients with retinopathy of prematurity. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70(1):19–21. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492007000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AC, Maldonado R, Sarin N, O’Connell RV, Wallace DK, Freedman SF, Cotton M, Stinnett SS, Toth CA. Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography as an Adjunct to Indirect Ophthalmoscopy for Retinopathy of Prematurity. Retina. 2011 doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821dfa6d. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinekar A, Sivakumar M, Shetty R, et al. A novel technique using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (Spectralis, SD-OCT+HRA) to image supine nonanaesthetized infants: utility demonstrated in aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Eye (Lond) 2010;24(2):379–382. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel CK. Optical coherence tomography in the management of acute retinopathy of prematurity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(3):582–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott AW, Farsiu S, Enyedi LB, Wallace DK, Toth CA. Imaging the infant retina with a hand-held spectral-domain optical coherence tomography device. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(2):364–373. e362. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sturm V, Landau K, Menke MN. Optical coherence tomography findings in Shaken Baby syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(3):363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koozekanani DD, Weinberg DV, Dubis AM, Beringer J, Carroll J. Hemorrhagic Retinoschisis in Shaken Baby Syndrome Imaged with Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010:1–3. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100215-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong GT, Farsiu S, Freedman SF, et al. Abnormal foveal morphology in ocular albinism imaged with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(1):37–44. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McAllister JT, Dubis AM, Tait DM, et al. Arrested development: high-resolution imaging of foveal morphology in albinism. Vision Res. 2010;50(8):810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maldonado RS, Freedman SF, Cotten CM, Ferranti JM, Toth CA. Reversible retinal edema in an infant with neonatal hemochromatosis and liver failure. J AAPOS. 2011;15(1):91–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson SG, Mohindra I, Held R. Visual acuity of infants with ocular diseases. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93(2):198–209. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer DL, Fulton AB, Rodier D. Grating and recognition acuities of pediatric patients. Ophthalmology. 1984;91(8):947–953. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu SJ, Li XT, Nicholas P, Toth CA, Izatt JA, Farsiu S. Automatic segmentation of seven retinal layers in SDOCT images congruent with expert manual segmentation. Opt Express. 2010;18(18):19413–19428. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.019413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muni RH, Kohly RP, Sohn EH, Lee TC. Hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography finding in shaken-baby syndrome. Retina. 2010;30(4 Suppl):S45–S50. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181dc048c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maldonado RS, O’Connell RV, Sarin N, Freedman SF, Wallace DKCM, Winter KP, Stinnett SS, Chiu SJ, Izatt JA, Farsiu S, Toth CA. Dynamics of human foveal development after premature birth. Ophthalmology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.028. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emerson MV, Pieramici DJ, Stoessel KM, Berreen JP, Gariano RF. Incidence and rate of disappearance of retinal hemorrhage in newborns. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(1):36–39. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes LA, May K, Talbot JF, Parsons MA. Incidence, distribution, and duration of birth-related retinal hemorrhages: a prospective study. J AAPOS. 2006;10(2):102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sunness JS, Haller JA, Fine SL. Central serous chorioretinopathy and pregnancy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(3):360–364. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090030078043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sihota R, Bose S, Paul AH. The neonatal fundus in maternal toxemia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1989;26(6):281–284. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19891101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendrickson AE, Yuodelis C. The morphological development of the human fovea. Ophthalmology. 1984;91(6):603–612. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Springer AD, Hendrickson AE. Development of the primate area of high acuity. 1. Use of finite element analysis models to identify mechanical variables affecting pit formation. Vis Neurosci. 2004;21(1):53–62. doi: 10.1017/s0952523804041057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuodelis C, Hendrickson A. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the human fovea during development. Vision Res. 1986;26(6):847–855. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(86)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahi JS, Cumberland PM, Peckham CS. Myopia Over the Lifecourse: Prevalence and Early Life Influences in the 1958 British Birth Cohort. Ophthalmology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attebo K, Mitchell P, Cumming R, Smith W, Jolly N, Sparkes R. Prevalence and causes of amblyopia in an adult population. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(1):154–159. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)91862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourne RR, Dineen BP, Ali SM, Noorul Huq DM, Johnson GJ. Prevalence of refractive error in Bangladeshi adults: results of the National Blindness and Low Vision Survey of Bangladesh. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(6):1150–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nangia V, Jonas JB, Sinha A, Matin A, Kulkarni M. Refractive error in central India: the Central India Eye and Medical Study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(4):693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng CY, Hsu WM, Liu JH, Tsai SY, Chou P. Refractive errors in an elderly Chinese population in Taiwan: the Shihpai Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(11):4630–4638. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schellini SA, Durkin SR, Hoyama E, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors in a Brazilian population: the Botucatu eye study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009;16(2):90–97. doi: 10.1080/09286580902737524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chia A, Dirani M, Chan YH, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in young singaporean chinese children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(7):3411–3417. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jamali P, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Younesian M, Jafari A. Refractive errors and amblyopia in children entering school: Shahrood, Iran. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86(4):364–369. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181993f42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in African-American and Hispanic preschool children: the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(10):1990–2000. e1991. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in white and African American children aged 6 through 71 months the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2128–2134. e2121–e2122. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.