The MITD1 is an largely uncharacterized MIT domain–containing protein. This protein localizes to the midbody, with its recruitment dependent on selective interactions with a number of ESCRT-III proteins. These interactions are required for proper abscission.

Abstract

Diverse cellular processes, including multivesicular body formation, cytokinesis, and viral budding, require the sequential functions of endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRTs) 0 to III. Of these multiprotein complexes, ESCRT-III in particular plays a key role in mediating membrane fission events by forming large, ring-like helical arrays. A number of proteins playing key effector roles, most notably the ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities protein VPS4, harbor present in microtubule-interacting and trafficking molecules (MIT) domains comprising asymmetric three-helical bundles, which interact with helical MIT-interacting motifs in ESCRT-III subunits. Here we assess comprehensively the ESCRT-III interactions of the MIT-domain family member MITD1 and identify strong interactions with charged multivesicular body protein 1B (CHMP1B), CHMP2A, and increased sodium tolerance-1 (IST1). We show that these ESCRT-III subunits are important for the recruitment of MITD1 to the midbody and that MITD1 participates in the abscission phase of cytokinesis. MITD1 also dimerizes through its C-terminal domain. Both types of interactions appear important for the role of MITD1 in negatively regulating the interaction of IST1 with VPS4. Because IST1 binding in turn regulates VPS4, MITD1 may function through downstream effects on the activity of VPS4, which plays a critical role in the processing and remodeling of ESCRT filaments in abscission.

INTRODUCTION

The endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery has been implicated in a number of cellular processes, including multivesicular body (MVB) formation, viral budding, and abscission during cytokinesis (reviewed in Hurley, 2010; Hurley and Hanson 2010; Henne et al., 2011; Schmidt and Teis, 2012). Components of the ESCRT machinery include ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III, the ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities (AAA) protein VPS4, the ALIX homodimer, and associated regulatory proteins. ESCRT-III comprises at least 12 structurally related subunits in humans, comprising charged MVB proteins 1–7 (CHMP1–7) and increased sodium tolerance-1 (IST1). These proteins adopt closed (autoinhibited) and open conformations that are associated with monomeric or oligomeric states, respectively (Lata et al., 2008; Bajorek et al., 2009b). ESCRT-III subunits form membrane-bound helical filaments, which promote changes in membrane structure, mediating membrane fission in a number of cellular contexts (reviewed in Hurley, 2010; Hurley and Hanson 2010; Henne et al., 2011; Guizetti and Gerlich, 2012; Schmidt and Teis, 2012).

ESCRT-III proteins harbor helical domains known as present in microtubule-interacting and trafficking molecules (MIT)–interacting motifs (MIMs) in their C-terminal regions that interact with MIT domains present in a variety of proteins. MIT domains are asymmetrical three-helix bundles, and many MIT domain–containing proteins are recruited to cellular compartments via interactions of their MIT domains with MIMs of specific ESCRT-III proteins (Obita et al., 2007; Stuchell-Brereton et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2008; Agromayor et al., 2009; Osako et al., 2010). The effector functions of proteins harboring MIT domains typically depend on other regions of the proteins, for example, the AAA domains of VPS4 and spastin (reviewed in Hill and Babst, 2012; Lumb et al., 2012). Several ESCRT-III– and MIT domain–containing proteins are mutated in inherited neurological disorders, including frontotemporal dementia and hereditary spastic paraplegia (Skibinski et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2007; Blackstone, 2012), emphasizing further the importance of ESCRT-dependent cellular processes.

The specificity of ESCRT interactions is highlighted by multiple modes of interaction, with different specificities among the various ESCRT subunits and MIT proteins (Morita, 2012) mediated at the structural level by distinct interaction interfaces (Obita et al., 2007; Stuchell-Brereton et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2008). Although in many cases the reasons for this high degree of specificity are not clear, it seems reasonable to postulate that different ESCRTs play roles in recruitment of various effector proteins throughout the cell via interactions with MIT domains. The specificity of interaction with various MIT domain–containing proteins underscores the importance of determining the roles of various ESCRTs in different cellular processes.

Here we investigate the role of a largely uncharacterized protein MITD1, which harbors an MIT domain at its N-terminus but without other known interaction or effector motifs. We describe the self-interaction of the MITD1 protein and investigate the roles of its oligomerization and ESCRT-III interactions during cytokinesis.

RESULTS

Identification of MITD1 as an ESCRT-III–interacting protein

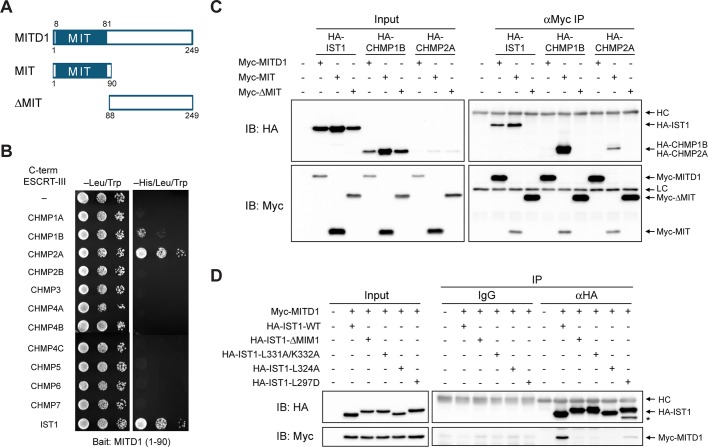

MITD1 is a 249–amino acid protein with an N-terminal MIT domain but no other known motifs (Figure 1A). There are clear homologues in Caenorhabditis elegans, Danio rerio, and Drosophila melanogaster, but not in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The MIT domain of human MITD1 (also known as LOC129531) was shown previously to interact with the MIM domain of the recently identified ESCRT-III protein IST1 (Agromayor et al., 2009), as well as with CHMP2A (Tsang et al., 2006). To examine whether the MIT domain of MITD1 interacts with MIM domains of other ESCRT-III subunits, we conducted yeast two-hybrid interaction tests using the 12 known human ESCRT-III proteins, comprising CHMP1–7 and IST1 (Renvoisé et al., 2010), as prey. The MITD1 MIT domain bait showed robust interactions with C-terminal constructs harboring MIM domains of CHMP1B, CHMP2A, and IST1 (Figure 1B). An interaction with CHMP1A was noted at longer growth times, but there was no interaction with other ESCRT-III subunits detected (Figure 1B and unpublished data).

FIGURE 1:

MIT domain of MITD1 selectively binds ESCRT-III proteins. (A) Schematic diagram showing the domain architecture of MITD1 and deletion mutants used in this study. Boundary amino acid residues are indicated. (B) Yeast two-hybrid interactions of the MIT domain of MITD1 with C-terminal MIM domains of ESCRT-III proteins were assayed using the HIS3 reporter (sequential 10-fold yeast dilutions are shown). (C) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated Myc-MITD1 constructs and HA-tagged IST1, CHMP1B, or CHMP2A. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc antibodies and immunoblotted (IB) for HA and Myc epitopes. (D) Interactions of Myc-MITD1 with various HA-IST1 MIM deletions and structure-based mutations were examined using coIP assays with HA-epitope antibodies or control immunoglobulin G (IgG). Immunoblotting was performed with HA- and Myc-epitope antibodies as indicated. An asterisk denotes a probable degradation product. HC, IgG heavy chain; LC, IgG light chain.

We confirmed the strongest yeast-two hybrid interactions in HEK293 cells using coimmunoprecipitation experiments. The isolated MIT domain (residues 1–90) of MITD1 interacted with full-length IST1, CHMP1B, and CHMP2A, whereas a MITD1 deletion mutant (residues 88–249) lacking the MIT domain did not (Figure 1, A and C). Of interest, although full-length MITD1 interacted detectably with IST1, full-length MITD1 did not bind CHMP1B or CHMP2A, despite the fact that both CHMP1B and CHMP2A interacted strongly with the isolated MIT domain of MITD1 (Figure 1C). This may reflect different degrees of autoinhibition among overexpressed ESCRT-III subunits (Yang et al., 2008; Bajorek et al., 2009b).

To establish whether the interactions of MITD1 with ESCRT-III proteins are mediated by MIM motifs of ESCRT-III proteins, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays using structure-based MIM mutants of IST1, mutating residues critical for the interaction of IST1 and VPS4A (Bajorek et al., 2009a). Because IST1 has two distinct MIM motifs (MIM1 and MIM2), we generated mutants for each MIM. All MIM1 mutations tested (ΔMIM1, L331A/K332A, and L324A) abolished the IST interaction with MITD1 (Figure 1D). A MIM2 mutation (L297D) also resulted in a significant reduction in binding to MITD1 (Figure 1D). These data indicate that IST1 interacts with MITD1 through its MIM motifs, particularly MIM1. Taken together, these results demonstrate that MITD1 binds to specific ESCRT-III proteins through selective MIT–MIM interactions.

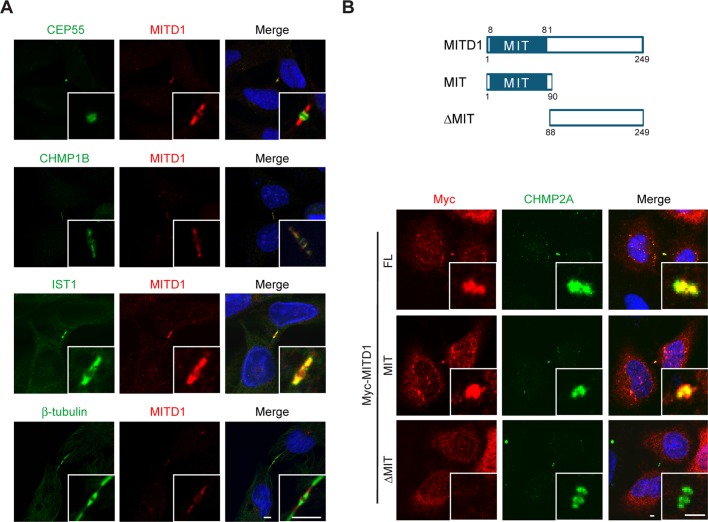

MITD1 localizes to the midbody through its MIT domain

To determine the subcellular localization of MITD1, particularly in dividing cells, we coimmunostained HeLa cells for endogenous MITD1 along with midbody marker proteins. When midbodies were stained using anti-CEP55 antibodies, we found that MITD1 localized at the periphery of CEP55 (Figure 2A, top); CEP55 localized to the Flemming body at the center of the midbody (Fabbro et al., 2005). CHMP1B and IST1 colocalized completely with MITD1, but the MITD1 signal did not track along microtubules labeled with anti–β-tubulin antibodies within the midbody (Figure 2A). Of interest, the MITD1 signal was observed at midbodies only when they appeared very thin (data not shown), suggesting that MITD1 may be recruited to the midbody during the terminal stage of abscission. This proposed recruitment timing is similar to that previously described for VPS4 (Morita et al., 2007).

FIGURE 2:

During cytokinesis, MITD1 localizes at the periphery of midbodies through its MIT domain. (A) HeLa cells were coimmunostained for endogenous MITD1 (red) and the indicated midbody marker proteins (green). Merged images are at the right, with DAPI nuclear staining in blue. Insets are enlarged images of the midbody region. Bars, 5 μm. (B) Top, schematic diagram showing the domain architecture of MITD1 and deletion mutants used; bottom, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated Myc-MITD1 constructs and coimmunostained for Myc-epitope (red) and endogenous CHMP2A (green). Merged images with DAPI are at the right. Insets are enlarged images of the midbody region. FL, full length. Bars, 2 μm.

To identify the domain required for midbody localization of MITD1, we examined the localization of transiently expressed full-length MITD1 or else truncation mutants in HeLa cells. Overexpressed full-length MITD1 and the isolated MIT domain of MITD1 colocalized with endogenous CHMP2A at the midbody (Figure 2B). However, ΔMIT MITD1 did not localize to the midbody. Thus the MIT domain is necessary and sufficient for midbody localization of MITD1.

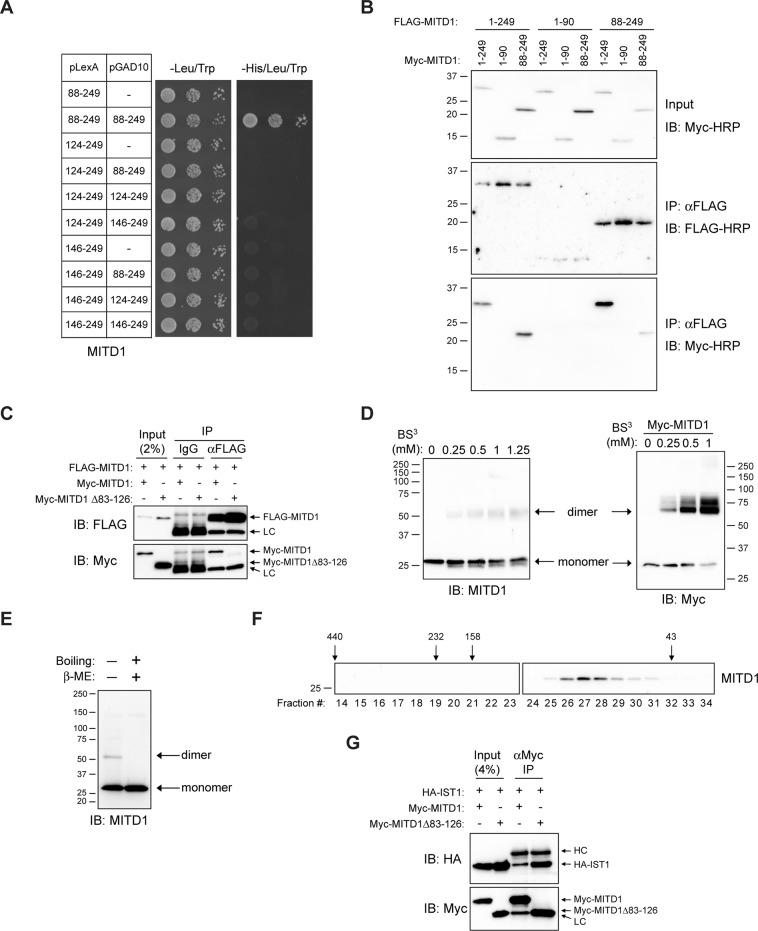

MITD1 is an oligomeric protein

To identify possible functions of MITD1, we performed yeast two-hybrid screening of a human brain library with the reporter strain NMY70 bearing the pLexA-N-ΔMIT MITD1(88–249) bait plasmid. From 1.87 × 107 yeast diploids screened, we recovered 59 prey constructs, comprising fragments of 10 different proteins. The highest number, 17, represented MITD1 itself (unpublished data). Of the 10 different proteins, only MITD1 could be confirmed as a bona fide interactor upon subsequent resynthesis of each prey, followed by retesting. As shown in Figure 3A, we generated various N-terminal deletion mutants in order to determine the minimal domain required for self-assembly. No deletion mutants tested beyond 88–249 showed positive interactions. We infer from these data that the residues 88–123 are necessary for self-assembly of MITD1.

FIGURE 3:

MITD1 can self-assemble through its C-terminal domain. (A) Yeast two-hybrid interactions between the indicated deletion mutants of MITD1 (boundary amino acid residues shown) were tested using the HIS3 reporter (sequential 10-fold yeast dilutions). (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated MITD1 constructs, and extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG-conjugated beads then immunoblotted (IB) for FLAG or Myc epitopes. (C) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated MITD1 constructs and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies or control IgG. Precipitates were then immunoblotted. (D) HEK293 cell lysates were treated with the indicated concentrations of BS3 and subjected to immunoblot analysis as indicated. (E) Cell lysates were prepared under the conditions shown and subjected to immunoblotting using anti-MITD1 antibodies. (F) Gel-exclusion FPLC was performed to determine the native size of endogenous MITD1. Aliquots of each fraction were immunoblotted with anti-MITD1 antibodies. Elution peaks for marker proteins (in kilodaltons) are across the top. (G) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with HA-IST1 and either full-length MITD1 or MITD1 Δ83–126. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibodies and analyzed by immunoblotting. In B, D, E, and F, sizes of protein standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated.

We performed coimmunoprecipitation assays with differential epitope tags to confirm the self-assembly of MITD1 in HEK293 cells. FLAG-tagged full-length and N-terminally truncated proteins coprecipitated with both Myc-tagged full-length and N-terminally truncated proteins (Figure 3B). However, the MITD1 MIT-domain construct (residues 1–90) did not interact with full-length MITD1 or any of the deletion constructs (Figure 3B). This result indicates that the C-terminal domain of MITD1 is necessary and sufficient for self-assembly. On the basis of the yeast-two hybrid results in Figure 3A, we constructed an MITD1 deletion mutant lacking residues 83–126. Although FLAG-tagged full-length MITD1 interacted with Myc-tagged full-length MITD1, it did not interact with the Myc-tagged MITD1 Δ83–126 mutant (Figure 3C), consistent with the yeast two-hybrid results. This further demonstrates that residues between 83 and 126 are required for self-assembly of MITD1 in cells.

Oligomerization of MITD1 was also examined by chemical cross-linking using bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3). For both endogenous and overexpressed MITD1 proteins, in BS3-treated lysates an additional band was observed at ∼60 kDa, consistent with the predicted size of a homodimer, in addition to the monomer at ∼29 kDa (Figure 3D). To investigate further the self-association of MITD1, we prepared protein samples under nonreducing conditions. When cell lysates were prepared for SDS–PAGE under nonreducing conditions (without β-mercaptoethanol) and not boiled, we observed the higher–molecular weight band in addition to the monomer band (Figure 3E). Using gel-exclusion fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC), we found that endogenous MITD1 eluted at a higher calculated molecular weight (∼77 kDa) than its monomer size (Figure 3F). Taken together, these results indicate that MITD1 exists as a homo-oligomer in vivo, most likely a dimer.

To assess the significance of MITD1 self-assembly, we tested whether self-association of MITD1 affects its interaction with IST1 (Figure 3G). We compared the binding of IST1 to MITD1 full-length and MITD1 Δ83–126 by coimmunoprecipitation. Both the MITD1 Δ83–126 mutant and full-length MITD1 bound to IST1, indicating that oligomerization is not required for this interaction. However, in these studies, we cannot rule out the possibility that oligomerization might modulate the interaction with IST1. We could not perform similar interaction studies of MITD1 with CHMP1B and CHMP2A because full-length MITD1 did not interact with these ESCRT-III subunits in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Figure 1C).

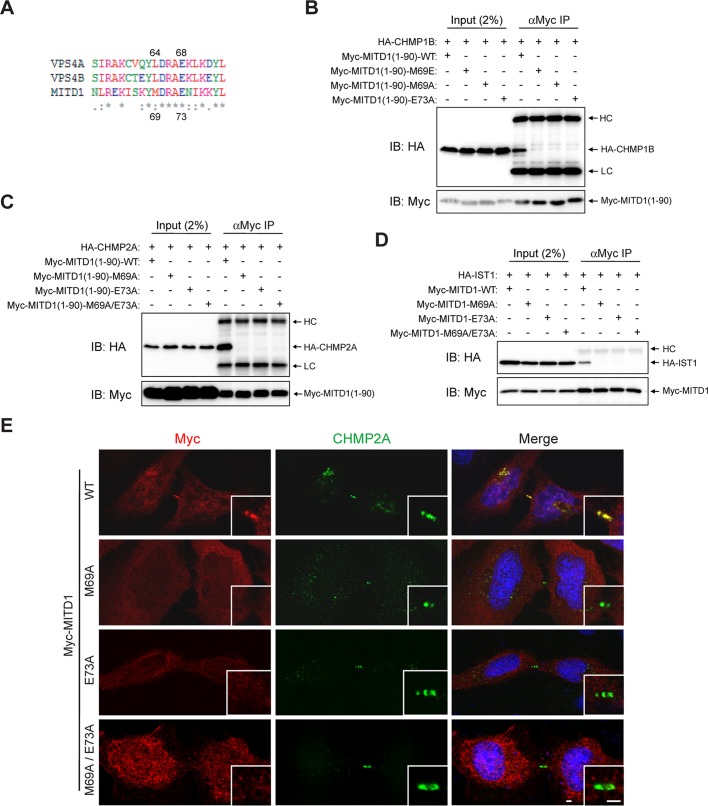

Recruitment of MITD1 to the midbody is regulated by ESCRT-III interactions

VPS4 recognizes and binds to the MIM motif of Vps2, the yeast orthologue of CHMP2, through critical residues in its MIT domain (Obita et al., 2007). When we aligned the MIT domain sequences of human VPS4A/B and MITD1 using ClustalW2 (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2), we found that a number of VPS4 residues required for interaction with Vps2 are identical to those in MITD1 (Figure 4A). Among these residues, we substituted Met-69 and Glu-73 of MITD1 with Ala because their corresponding residues, Leu-64 and Glu-68 of VPS4, form key interactions with the αC helix of CHMP2/Vps2 (Obita et al., 2007). When these missense mutants were overexpressed, the interactions of MITD1 with ESCRT-III proteins were abolished (Figure 4, B–D). From these results, we conclude that the MITD1 interface for ESCRT-III interaction is similar to that of VPS4 with CHMP2/Vps2.

FIGURE 4:

VPS4 residues required for ESCRT-III interaction are highly conserved in MITD1 and important for MITD1 midbody localization and ESCRT-III interaction. (A) Amino acid sequences of MIT domains of human MITD1 and VPS4A/B were aligned using ClustalW2. An asterisk indicates fully conserved residues. Colon indicates conservation between groups of strongly similar properties. Period indicates conservation between groups of weakly similar properties. (B–D) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc antibodies. Precipitates were then immunoblotted (IB) with anti–HA- and anti–Myc-epitope antibodies. (E) HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated Myc-MITD1 constructs and immunostained for Myc epitope (red) and CHMP2A (green). Insets are enlarged images of midbody regions. HC, IgG heavy chain; LC, IgG light chain; WT, wild type. Bars, 2 μm.

As shown in Figures 1C and 2B, the MIT domain of MITD1 is required for both its interactions with ESCRT-III proteins and its localization to the midbody. To establish whether the interactions between MITD1 and ESCRT-III mediate the midbody localization of MITD1, we investigated the subcellular localization of the structure-based MITD1 mutants that do not bind ESCRT-III. Whereas wild-type MITD1 was recruited to the midbody, none of the tested mutants (M69A, E73A, and M69A/E73A) were recruited to the midbody (Figure 4E). These data support the hypothesis that the recruitment of MITD1 to the midbody is mediated by specific interactions with ESCRT-III subunits.

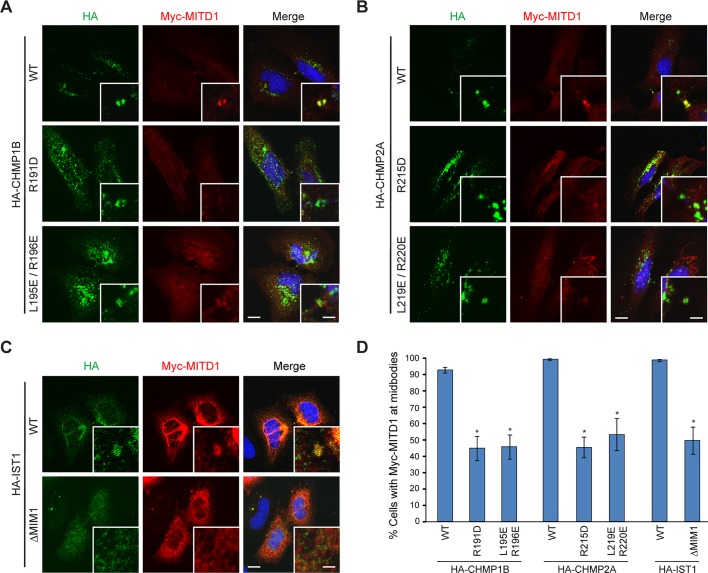

MIT domains interact with MIM motifs within ESCRT-III proteins. Our data demonstrating that mutations in the MIT domain of MITD1 inhibit its localization to the midbody prompted us to examine whether mutations in MIM domains of ESCRT-III proteins also affect the recruitment of MITD1 to the midbody. The MIT domain of VPS4 recognizes a (D/E)xxLxxRLxxL(K/R) motif within several ESCRT-III proteins (Obita et al., 2007; Stuchell-Brereton et al., 2007). On the basis of this motif, we introduced mutations into MIM domains of CHMP1B, CHMP2A, and IST1. When wild-type hemagglutinin (HA)-CHMP1B and HA-CHMP2A were coexpressed with Myc-MITD1 in HeLa cells, the ESCRT-III proteins and Myc-MITD1 localized to midbodies (Figure 5, A, B, and D). Even though all the ESCRT-III MIM mutants tested (R191D and L195E/R196E for CHMP1B, R215D and L219E/R220E for CHMP2A) localized to midbodies, the population of cells with Myc-MITD1 at the midbody was significantly decreased in MIM mutant–overexpressing cells (Figure 5, A, B, and D).

FIGURE 5:

MIM domains of ESCRT-III proteins regulate midbody localization of MITD1. (A–C) Myc-MITD1 was transfected into HeLa cells along with the indicated HA-tagged CHMP1B (A), CHMP2A (B), or IST1 (C) constructs. Cells were fixed and immunostained for HA (green) and Myc (red) epitopes. Merged images with DAPI staining are to the right. Insets are enlarged images of midbody regions. (D) Among cells expressing HA-tagged ESCRT-III proteins at the midbody, cells with Myc-MITD1 at the midbody were counted (50 cells per group, n = 3 independent experiments). Graphs express means ± SEM. *p < 0.05. WT, wild type. Bars, 10 μm, 2 μm (insets).

As can be seen in Figure 5C, MITD1 formed bundle-like structures when overexpressed along with IST1 wild-type or the MIM2 L297D mutant, but none of the IST1 MIM1 mutants (ΔMIM1, L324A, and L331A/K332A) induced these bundles (Figure 5C and unpublished data). These results mirror the MITD1–IST1 interaction and MITD1 midbody recruitment data. Although the nature of these bundled structures remains unclear, because MITD1 is an oligomer and ESCRT-III proteins can form large helical arrays, we speculate that their overexpression and interaction may nucleate or stabilize such higher-order structures.

MITD1 is required for efficient abscission

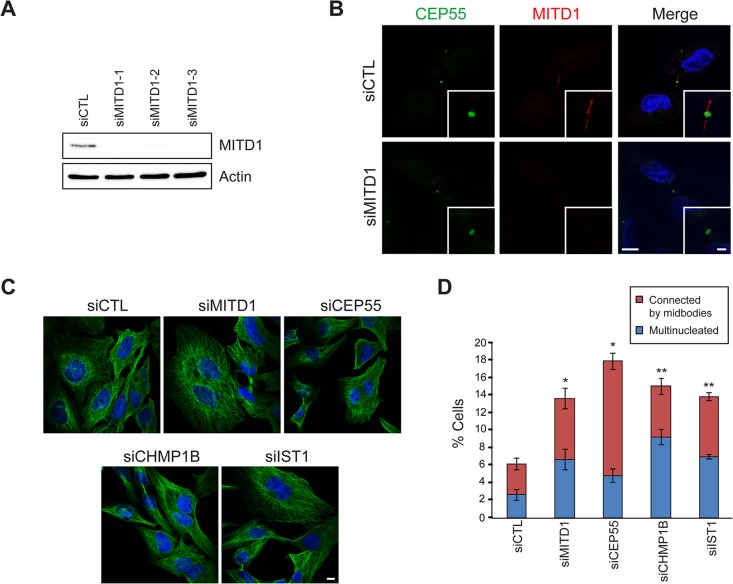

To investigate the role of MITD1 in cytokinesis, we depleted endogenous MITD1 using small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections. Three different siRNAs against MITD1 were examined, with similar results, to lessen the likelihood of off-target effects (Figure 6A). When HeLa cells transfected with siRNA against MITD1 were stained with anti-MITD1 antibodies, the immunoreactive signal was not present at the midbody or elsewhere in the cell (Figure 6B). Depletion of MITD1 resulted in a significant increase in the number of cells interconnected by midbodies, as well in as the percentage of multinucleated cells (Figure 6, C and D). This phenotype was highly comparable to that seen upon depletion of other proteins known to function in the abscission phase of cytokinesis (Fabbro et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2008; Agromayor et al., 2009; Bajorek et al., 2009a; Connell et al., 2009).

FIGURE 6:

MITD1 is involved in cytokinesis. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA (siCTL) or three different siRNAs against MITD1 (siMITD1). Cells were lysed and immunoblotted for MITD1. Actin levels were monitored to control for protein loading. (B) After the indicated siRNA transfections, cells were fixed and immunostained for CEP55 (green) and MITD1 (red). Merged images with DAPI staining are to the right. Insets are enlarged images of midbody regions. (C) HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were stained with β-tubulin antibodies (green) and DAPI (blue). (D) Cells interconnected by midbodies and multinucleated cells were counted based on DAPI and β-tubulin staining as shown in C. Five hundred cells per group were analyzed in three independent experiments and graphed (means ± SEM). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Bars, 10 μm (B, C), 2 μm (inset in B).

To characterize further the cytokinesis defects caused by MITD1 depletion, we performed time-lapse imaging of cell division for 16 h, beginning 32 h after siRNA transfection. Most control siRNA–treated cells (n = 65) that entered mitosis went through normal mitosis and completed abscission (197 ± 17 min; Figure 7, A and B, and Supplemental Movie S1). However, only 6% of MITD1-depleted cells (n = 49) completed cytokinesis successfully. The majority of MITD1-depleted cells underwent normal mitosis until the abscission phase; the period to complete abscission was extremely prolonged in these cells (511 ± 31 min; Figure 7, A and B, and Supplemental Movie S2). Even so, of the 49 MITD1-depleted cells examined, 16 cells failed to form midbodies (unpublished data). In these cells, chromosomes were segregated properly, and a cleavage furrow was observed; midbodies did not appear, and soon after formation of the cleavage furrow, the cells fused to form binucleated cells.

FIGURE 7:

Differential effects of MITD1 on cytokinesis and EGFR degradation. (A) Confocal time-lapse imaging of HeLa cells transfected with control (siCTL) or MITD1 (siMITD1) siRNA. Elapsed times (minutes) are provided in each panel. White arrowheads mark midbodies connecting two cells. Bars, 10 μm. (B) Time required to complete cytokinesis was measured from 65 control and 49 MITD1-depleted cells in three independent experiments (means ± SEM). ****p < 0.0001. (C) HeLa cells transfected with control (siCTL) or MITD1 (siMITD1) siRNA were serum starved and stimulated with EGF for the indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with EGFR, MITD1, and β-tubulin antibodies. (D) Graphical representation of quantified intensities of EGFR protein bands from three independent experiments.

Given that most ESCRT machinery proteins are also implicated in MVB biogenesis, we examined a role for MITD1 in this process by studying the degradation of the activated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Depletion of MITD1 by siRNA had no effect on EGFR degradation (Figure 7, C and D). This result is consistent with previous reports that depletion of IST1 does not affect EGFR degradation but does affect the completion of cytokinesis (Agromayor et al., 2009). From these data, we infer that the cytokinetic defects caused by MITD1 depletion are not an indirect consequence of disturbing functions of ESCRT proteins on MVB biogenesis.

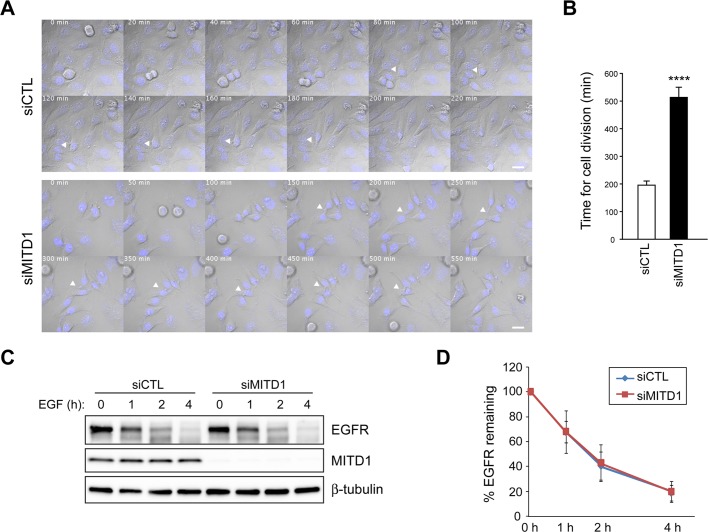

As shown in Figure 4, MITD1 mutants that could not bind to ESCRT-III proteins were not recruited to the midbody. We examined whether the midbody localization of endogenous MITD1 is dependent on CHMP1B, IST, or both. Depletion of CHMP1B or IST1 did not inhibit the formation of midbodies (Figure 8A). However, MITD1 was not recruited to midbodies efficiently when either CHMP1B or IST1 was depleted individually. Because depletion of CHMP1B or IST1 did not decrease protein levels of MITD1 (Supplemental Figure S1), we conclude that CHMP1B and IST1 do not affect MITD1 protein stability but rather the recruitment of MITD1 to the midbody.

FIGURE 8:

Midbody recruitment of MITD1 is regulated by ESCRT-III. (A) HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were stained for endogenous MITD1 (green) and β-tubulin (red). Cells with MITD1 signal enriched at midbodies were counted from 100 cells per group, n = 3 independent experiments. Graphs express means ± SEM. ***p < 0.001. (B, C) HeLa cells were transfected with control (siCTL) or MITD1 (siMITD1) siRNA and costained for CHMP2A (red) along with CHMP1B (B) or IST1 (C) (green). Merged images with DAPI staining are at the right. Insets are enlargements of midbody regions. Bars, 5 μm.

Depletion of MITD1 perturbed efficient abscission (Figure 6). Given that ESCRT machinery proteins are important players at the midbody to complete abscission, we examined whether depletion of MITD1 affects the midbody recruitment of ESCRT proteins. First, we tested the localization of CEP55, which is important in organizing the Flemming body and recruits a series of ESCRT proteins such as Tsg101 and ALIX to the midbody (Morita et al., 2007; Caballe and Martin-Serrano, 2011). CEP55 was clearly present at the Flemming body after MITD1 depletion (Figure 6B and Supplemental Figure S2A). Next we examined the midbody recruitment of the ESCRT-III proteins that had been identified as strong interacting partners of MITD1. The midbody recruitment of CHMP1B, CHMP2A, and IST1 was not affected by MITD1 depletion (Figure 8, B and C, and Supplemental Figures S2A and S3). The midbody localization of CHMP5, another ESCRT-III protein, was also not disturbed (Supplemental Figure S2B). To examine whether midbody composition is compromised in MITD1-depleted cells, we observed the localization of Aurora B, a mitotic kinase that functions at the midzone, and MKLP1, a subunit of the centralspindlin complex, after MITD1 depletion. Although the region of Aurora B distribution at the midzone tended to become more elongated, Aurora B and MKLP1 localized properly (Supplemental Figure S2C). These results indicate that depletion of MITD1 does not compromise generally the formation and composition of the midbody but instead induces cytokinetic defects directly as a result of impairment of MITD1 function.

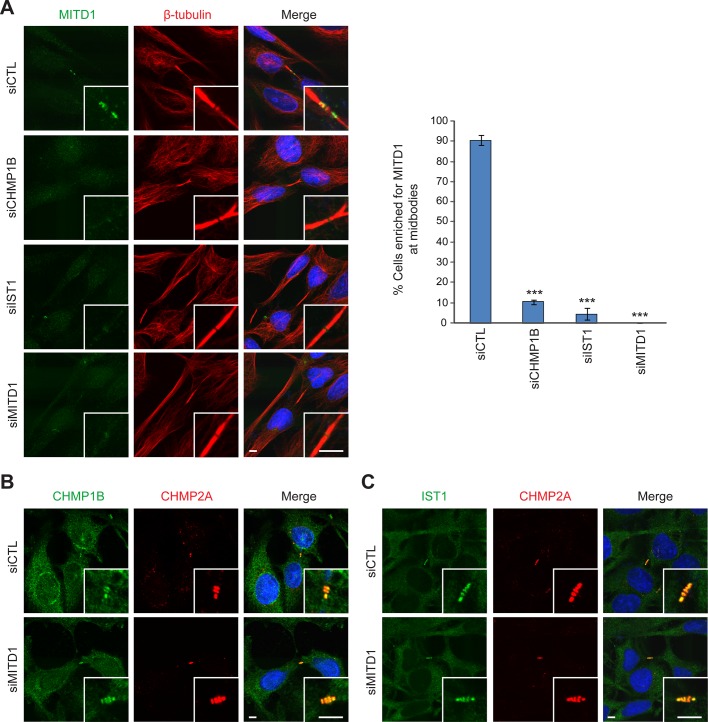

To analyze the effects of different MITD1 mutation on cytokinesis, we generated siRNA-resistant forms of MITD1 by introducing four silent point mutations into the sequence targeted by the MITD1 siRNA. These were used to establish HeLa cell lines stably expressing wild-type MITD1 or else mutants deficient in interaction with ESCRT-III and midbody localization, allowing us to examine whether recruitment of MITD1 to the midbody is required for proper cytokinesis. All stable cell lines expressed similar levels of ectopic proteins, resistant to the effects of MITD1 siRNA as compared with those of endogenous MITD1 proteins (Figure 9A). Endogenous MITD1 proteins were depleted in MITD1 siRNA–transfected cells, whereas levels of siRNA-resistant MITD1 proteins were equivalent to those in control cells. We examined the subcellular localization of stably expressed MITD1 proteins by immunostaining after first depleting endogenous MITD1 via siRNA transfection. Stably expressed, wild-type MITD1 localized to the midbody in a manner highly similar to that of endogenous MITD1 visualized in empty-vector–expressing cells (Figure 9B). All MITD1 mutants defective in ESCRT-III interaction failed to localize properly to the midbody. By contrast, the MITD1 Δ83–126 mutant defective in oligomerization localized to the midbody normally.

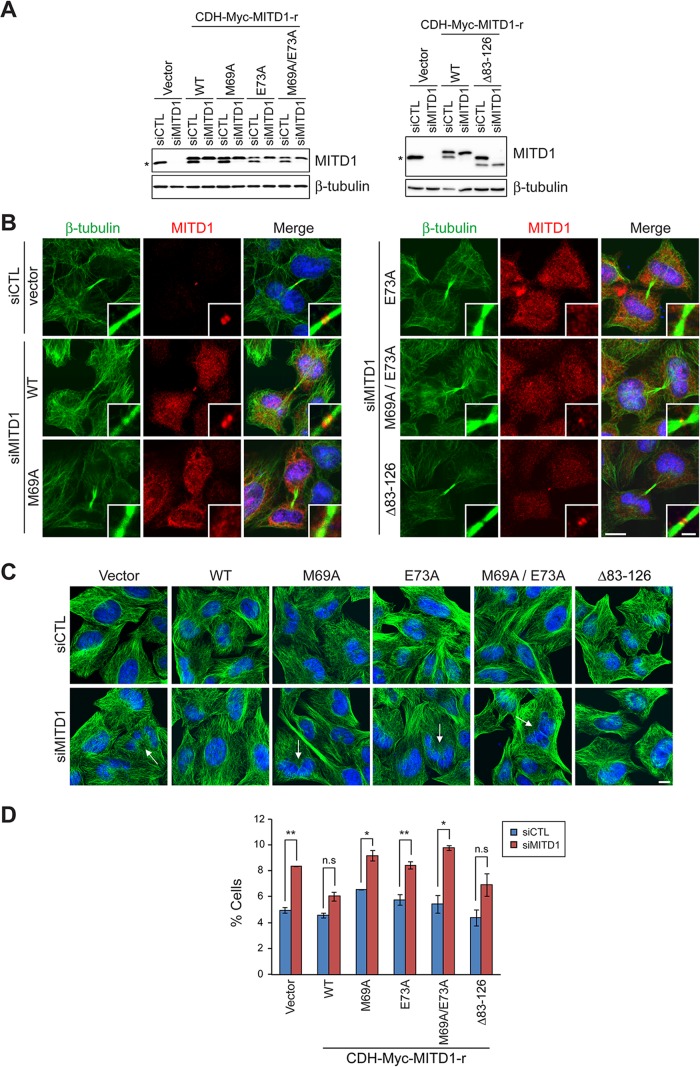

FIGURE 9:

Recruitment of MITD1 to the midbody by ESCRT-III is required for completion of cytokinesis. (A) HeLa cells stably expressing empty vector or the indicated Myc-tagged, siRNA-resistant MITD1 constructs were transfected with either control (siCTL) or MITD1 (siMITD1) siRNA. Cells were lysed 48 h later, and extracts were immunoblotted for MITD1 (endogenous and recombinant) or β-tubulin. An asterisk denotes endogenous MITD1. (B) Localizations of stably expressed recombinant proteins were examined by staining siMITD1-transfected cells with MITD1 (red) and β-tubulin (green) antibodies. For comparisons with endogenous MITD1, cells stably expressing empty vector were transfected with siCTL and stained with indicated antibodies. Merged images with DAPI staining are to the right. (C) HeLa cells stably expressing empty vector or various MITD1 constructs were transfected with siCTL or siMITD1 and stained with β-tubulin (green) antibodies. Arrows indicate multinucleated cells. (D) Cells interconnected by midbodies and multinucleated cells were counted based on DAPI and β-tubulin staining as shown in C. Five hundred cells per group were analyzed in three independent experiments. Graphs express means ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; n.s., not significant. Bars, 10 μm (B, C), 2 μm (inset in B).

We examined whether the abscission defects caused by depletion of MITD1 could be rescued by various MITD1 mutants by counting the multinucleated cells and cells interconnected by midbodies. As expected, wild-type MITD1 rescued the phenotype in MITD1 siRNA–transfected cells (Figure 9, C and D). However, none of the MITD1 MIT-domain mutants defective in ESCRT-III interaction could rescue the cytokinetic defects. From these results, we conclude that the recruitment of MITD1 to the midbody by ESCRT-III proteins is required for completion of cytokinesis.

The effects of the MITD1 Δ83–126 mutant on rescuing cytokinetic defects were also examined (Figure 9, C and D). Because the MITD1 Δ83–126 mutant rescued the cytokinetic defects caused by depletion of MITD1, we postulated that self-assembly of MITD1 is not required for its effects on cytokinesis. However, there was a clear trend toward incomplete rescue, and it is possible that MITD1 oligomerization plays a modulatory role.

MITD1 competes with VPS4 for interaction with IST1

To investigate the mechanistic role of MITD1 in the completion of cytokinesis, we examined whether MITD1 regulates the recruitment of VPS4 to the midbody by ESCRT-III. IST1 interacts with VPS4 and regulates its localization and assembly (Dimaano et al., 2008). Because MITD1 also binds IST1 strongly, we examined whether the dosage of MITD1 affects the interaction between IST1 and VPS4 in cells. When only IST1 and VPS4 were overexpressed in HEK293 cells, VPS4 exhibited a strong interaction with IST1 (Figure 10A). However, when MITD1 was overexpressed as well, binding of VPS4 to IST1 was significantly decreased. Given that MITD1 does not bind VPS4 directly (Supplemental Figure S4), MITD1 might inhibit the interaction between IST1 and VPS4 by competitively binding to IST1.

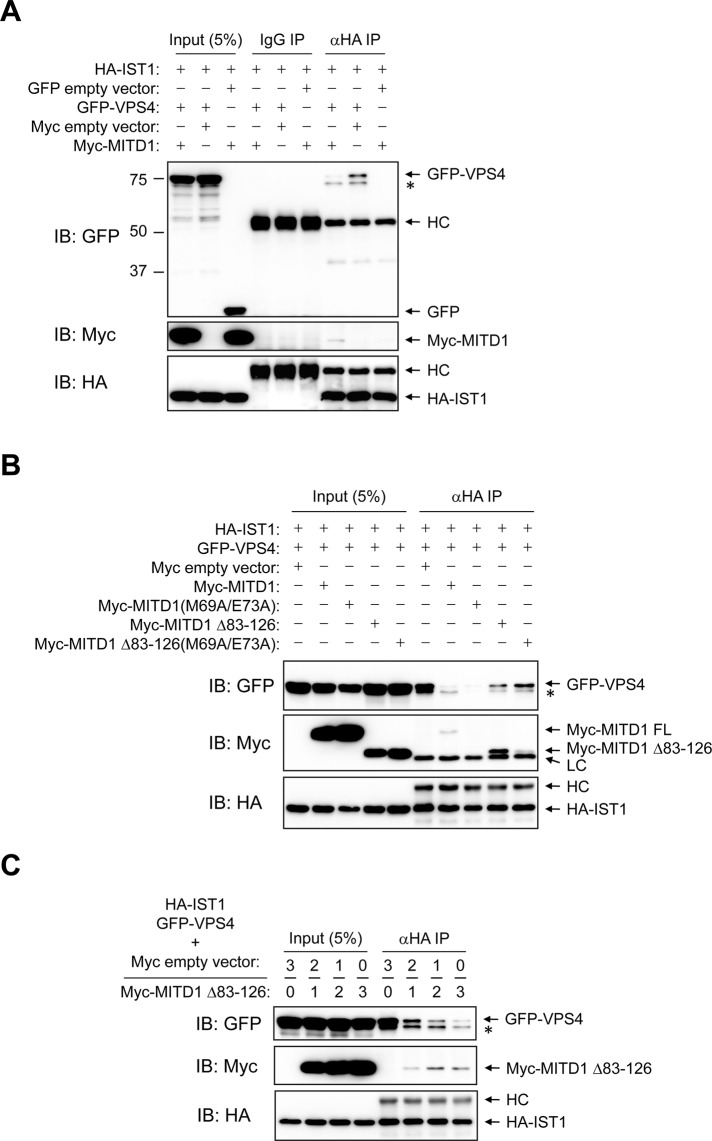

FIGURE 10:

MITD1 competes with VPS4 for binding to IST1. (A, B) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated constructs. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti–HA-epitope antibodies or control IgG. Immunoblotting (IB) was performed with GFP, Myc-epitope, and HA-epitope antibodies as indicated. (C) HA-IST1 and GFP-VPS4 constructs were cotransfected into HEK293 cells with Myc-empty vector or Myc-MITD1 Δ83–126. Molar ratios of Myc-empty vector and Myc-MITD1 Δ83–126 DNA are shown along the top. The amount of GFP-VPS4 DNA was held constant, whereas the amount of Myc-MITD1 Δ83–126 DNA was varied. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with HA-probe antibodies. Immunoblotting (IB) was performed for GFP, Myc epitope, and HA epitope as indicated. An asterisk denotes a probable degradation product or modified form of GFP-VPS4. HC, IgG heavy chain; LC, IgG light chain.

To test this hypothesis, we examined an MITD1 mutant (M69A/E73A) that cannot bind to IST1, in comparison with wild-type MITD1. Against initial expectations, the MITD1 (M69A/E73A) mutant showed the same inhibitory effect on binding of VPS4 to IST1 (Figure 10B). Even so, there was the possibility that MITD1 self-assembly could inhibit its binding activity to IST1, as shown earlier in Figure 3G. Thus we produced another mutant, MITD1 Δ83–126 (M69A/E73A), which cannot oligomerize and cannot bind to IST1, for comparison with the MITD1 Δ83–126 protein that binds IST1 in cells (Figure 3G). Surprisingly, MITD1 Δ83–126 showed a milder inhibition than wild-type MITD1 even though it binds IST1 more robustly (Figure 10B). When MITD1 Δ83–126 (M69A/E73A) was cotransfected, the amount of VPS4 binding to IST1 was increased to a greater degree than when MITD1 Δ83–126 was cotransfected (Figure 10B). These results suggest that IST1-binding activity and oligomerization of MITD1 can negatively regulate the interaction of VPS4 with IST1.

We confirmed this negative regulatory effect of MITD1 by using a competition assay. MITD1 Δ83–126 was used in the experiment instead of wild-type MITD1 because it binds IST1 more effectively. Although the amount of GFP-VPS4 DNA was held constant, the amount of Myc-MITD1 Δ83–126 DNA was varied, with the total DNA transfected kept constant with the addition of Myc empty vector (Figure 10C). As the amount of MITD1 Δ83–126 was increased, VPS4 binding to IST1 was decreased. The same competition assay was done using the AAA spastin because spastin also harbors an MIT domain and binds to IST1 (Agromayor et al., 2009; Renvoisé et al., 2010). However, the binding activity of spastin to IST1 was unaffected by MITD1 Δ83–126 (Supplemental Figure S5), showing that MITD1 might selectively regulate VPS4 binding to IST1. Taken together, our results demonstrate that MITD1 competes with VPS4 for interaction with IST1. Given that IST1 interaction alters VPS4 function, this suggests a mechanistic role for MITD1 in the abscission phase of cytokinesis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the high-affinity, selective interactions of the MIT domain of MITD1 with a number of ESCRT-III subunits: IST1, CHMP1B, and CHMP2A. Using structure-based mutations to investigate the role of ESCRT-III interactions selectively, we found that MITD1 is recruited to midbodies during the abscission phase of cytokinesis by ESCRT-III, and this recruitment is required for efficient abscission. Of interest, depletion of either CHMP1B or IST1 in HeLa cells dramatically reduced MITD1 recruitment to midbodies, suggesting that there is little redundancy or excess capacity among the ESCRT-III subunits.

A recurring theme among ESCRT-III proteins is that they likely are present in an autoinhibited conformation in cells (Lata et al., 2008; Bajorek et al., 2009b). This autoinhibition may be released as ESCRT-III forms multimeric circular arrays during cytokinesis (Hanson et al., 2008), permitting interactions of ESCRT-III MIMs with MIT domain–containing proteins such as the AAAs spastin and VPS4 and probable adaptor proteins such as spartin (Renvoisé et al., 2010; Hill and Babst, 2012; Lumb et al., 2012) in a regulated manner. Along these lines, we found that co-overexpression of ESCRT-III with MITD1 resulted in large, intracellular, bundle-like structures with the cells. We speculated that because MITD1 is an oligomer as well, it may be able to modulate the assembly/disassembly of ESCRT-III higher-order structures. Consistent with this notion, we did not uncover any interactions other than self-interactions in a yeast two-hybrid screen using a MITD1 construct lacking the MIT domain as bait, and it has no known motifs other than its MIT domain. Furthermore, residues required for VPS4 interaction with CHMP2 are also required for the MITD1–ESCRT-III interactions reported here, and thus we postulated that MITD1 interactions may inhibit VPS4 interaction with ESCRT-III complexes and thus their subsequent disassembly.

In fact, we present direct evidence that MITD1 can selectively interfere with IST1 binding to VPS4 but not with the AAA spastin, which severs microtubules, providing specific regulation of VPS4 activity. One explanation for this difference is that canonical MIT–MIM interactions (including those of VPS4) occur through an interface between helices α2 and α3 of the MIT domain, with an affinity in the range of Kd ≈ 30 μM by surface plasmon resonance (Stuchell-Brereton et al., 2007). However, the noncanonical interaction of spastin with CHMP1B and IST1 occurs at a larger interface between MIT helices α1 and α3, with a substantially binding higher affinity in the range of Kd ≈ 4–12 μM (Yang et al., 2008). In fact, the spastin–IST1 interaction has among the highest reported MIT–MIM binding affinities, with Kd = 4.6 μM (Renvoisé et al., 2010). The dramatic difference in MIT–MIM binding affinities provides a compelling explanation for the differential effects of MITD1 on VPS4 and spastin interactions with IST1.

We focused on the effects of MITD1 on abscission during cell division and in fact did not find any effect of MITD1 depletion on other ESCRT-mediated functions such as EGFR degradation in cells. Increasingly, it is being recognized that ESCRT dynamics between, for example, viral budding and cytokinesis can be quite distinct, which might reflect differences in spatiotemporal regulation of VPS4 function. Thus a simpler ESCRT-III disassembly and recycling cycle may occur in MVB sorting and viral budding, with a more protracted and defined ESCRT-III filament remodeling during cytokinesis (Mueller et al., 2012). In this scenario modulation of VPS4 activity would be crucial, with proteins such as MITD1 playing specific regulatory roles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructs

The human MITD1 coding sequence (GenBank NM_138798) comprising residues 1–90 was cloned into the EcoRI site of yeast two-hybrid bait vector pGBKT7 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Full-length MITD1 and various deletion mutants were cloned into the mammalian expression vectors pGW1-Myc (Zhu et al., 2003) and pCMV-Tag2B (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Amino acid numbering for IST1 throughout this article refers to isoform d (GenBank NP_001257906).

The pGAD10 and pGADT7 prey vectors (Clontech) for CHMP1-7 and IST1 were described previously (Yang et al., 2008; Renvoisé et al., 2010). CHMP1B, CHMP2A, and IST1 were also cloned into the mammalian expression vector pGW1-HA, producing a HA tag at the N-terminus (Zhu et al., 2003). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)–tagged human VPS4A was a gift from W. Sundquist (Garrus et al., 2001). Human spastin (M87 isoform) tagged with Myc at the N-terminus was described in Yang et al. (2008). Point mutations were introduced using QuikChange (Agilent Technologies). For producing lentivirus, wild-type and various mutants of MITD1 were cloned into the EcoRI site of pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro lentiviral vector (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA; the sequence for the c-Myc epitope was cloned into the XbaI and EcoRI sites). All MITD1 lentiviral constructs were modified to introduce siRNA-resistant silent mutations against the siMITD1 #2 target sequence. All vector constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Yeast two-hybrid studies

Yeast two-hybrid assays using the AH109 yeast strain were performed as described previously (Rismanchi et al., 2008; Park et al., 2010), and the ESCRT-III prey constructs were described in Yang et al. (2008) and Renvoisé et al. (2010). A yeast two-hybrid screen was conducted commercially using MITD1 (88–249) cloned into the EcoRI site of the pLexA-N vector. Reporter strain NMY70 harboring this bait was used to screen a normalized human brain library prepared in the pGADT7-recAB prey vector (complexity 3.2 × 106). Of 1.87 × 107 diploids screened, 59 putative interactors were successfully rescued and sequenced (DualSystems Biotech, Schlieren, Switzerland).

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used against MITD1 (Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL), CHMP2A (Proteintech Group), EGFR (1005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), MKLP1 (N-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and HA epitope (Y-11; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Mouse monoclonal antibodies were used against IST1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), β-tubulin (IgG1, clone D66; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), actin (clone AC-40; Sigma-Aldrich), Aurora B (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), Myc epitope (clone 9E10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), HA probe (F-7; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GFP (clones 7.1 and 13.1; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), and FLAG epitope (clone M2; Sigma-Aldrich). Mouse polyclonal CEP55 and CHMP1B antibodies were obtained from Abnova (Taipei City, Taiwan). Goat polyclonal CHMP5 antibodies were obtained from Abcam. Goat monoclonal Myc antibodies were obtained from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX). To avoid signals from mouse light chain, horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies against Myc-epitope (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and FLAG-epitope (Sigma-Aldrich) were used in Figure 3B.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa and HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Transfection was performed by using GenJet Plus (SignaGen Laboratories, Rockville, MD) for plasmid DNA and Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for siRNA as manufacturer's instructions. The siRNA sequences used were as follows: MITD1 #1, 5′-GUGCUGUUGGAAGUUCAAUACUCUU-3′; MITD1 #2, 5′-AAGAGUAUUGAACUUCCAACAGCAC-3′; MITD1 #3, 5′-UACAUGACCGAGAAAUUAGGUUCAA-3′; Cep55, 5′-GGAACAACAGAUGCAGGCAUGUACU-3′; CHMP1B, 5′-UCGACCUCAACAUGGAGCUGCCGCA-3′ (Yang et al., 2008); and IST1, 5′-CCAGUCAGAAGUGGCUGAGUUGAAA-3′ (Renvoisé et al., 2010). Control siRNAs were obtained from Ambion (Austin, TX).

Generation of stable HeLa cell lines

HEK293 cells were cotransfected with pCMV-dR8.2 dvpr, pCMV-VSV-G (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) and the respective pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro-Myc-based constructs. The next day, lentivirus was harvested from the culture media and frozen at −80°C. HeLa cells were infected with the indicated virus, and 24 h later they were incubated with 2 μg/ml puromycin for 2–3 d for selection.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

HeLa cells seeded on cover slips were fixed with cold methanol for 10 min. The fixed cells were blocked with 5% donkey serum in PBST (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Triton X-100) for 20 min at room temperature. Then cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 5% donkey serum diluted in PBST for 2 h, washed four times with PBST, incubated with Alexa Fluor anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) diluted in 5% donkey serum in PBST for 30 min, and washed with PBST four times. For nuclear staining, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) solution was applied for 5 min. Cells were mounted on a slide glass using Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL). Cells were observed using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a 63×/1.4 numerical aperture Plan-Apochromat lens, and image acquisition and processing were performed using ZEN 2009 software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging). Images were edited using Photoshop 7.0 and Illustrator CS2 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Statistical significance was assessed using Student's t test.

For live-cell imaging experiments, HeLa cells were cultured on glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA), and cotransfected with siRNA and pmaxGFP (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) to label transfected cells. At 30 h posttransfection, cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) for 3 min and washed twice, and warm media was applied. Time-lapse recordings were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope (Zeiss/PeCon [Erbach, Germany] XL LSM 710S1 live-cell incubator system with TempModule S, CO2 Module S1, and Heating Unit XL S) fitted under thermostat conditions (37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified chamber). Images were acquired with a 40×/1.4 numerical aperture Plan-Apochromat oil differential interference contrast (DIC) objective as one picture of 1-μm z-stacks at 10-min intervals, together with a single DIC reference image for 16 h. Images were exported in 8-bit TIFF format using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). For quantification, DIC images were used to determine the timing of mitosis. Images were processed using ImageJ and Photoshop 7.0 software.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

For immunoprecipitation studies, HEK293 cells were collected in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitor cocktail) for 30 min, clarified by centrifugation (4°C, 14,000 × g, 30 min), and incubated with antibodies (1 μg) at 4°C overnight. Protein A/G PLUS-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added for 1 h, and then beads were washed three times with lysis buffer. Bound proteins were resolved on SDS–PAGE gels and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Zhu et al., 2003), and images were obtained and processed using the ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Chemical cross-linking and gel-exclusion FPLC

HEK293 cells were washed three times with cold PBS to remove amine-containing culture media and proteins. Cells were then scraped in cold PBS and homogenized. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation and then treated with BS3 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) on ice for 2 h (Zhu et al., 2004). To quench the reaction, 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was added to a final concentration of 30 mM for 15 min at room temperature. Cross-linked products were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting.

FPLC was performed as described previously with minor modifications (Zhu et al., 2003, 2004). Samples were applied to a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) at a flow rate of 0.25 ml/min in PBS. Fractions (0.25 ml) were collected, and aliquots were subjected to immunoblotting. Protein standards (Sigma-Aldrich and GE Healthcare) in PBS were applied to the column to generate a standard curve, from which the native molecular weight for endogenous MITD1 was estimated.

EGFR degradation assay

HeLa cells transfected with either control siRNA or MITD1 siRNA were serum starved in the presence of cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) for 1 h and treated with EGF (0.5 μM) in the presence of cycloheximide and serum. At the indicated times, cells were washed rapidly with PBS, lysed with Laemmli sample buffer, and analyzed by immunoblotting. To quantify the degradation of EGFR, the intensity of EGFR immunoreactive bands at each time point was measured using Image Lab 3.0.1 software (Bio-Rad). The intensity of EGFR was normalized to the intensity of the corresponding β-tubulin immunoreactive band.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Nagle and D. Kauffman (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke DNA Sequencing Facility) for DNA sequencing. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, and the National Institutes of Health Clinical Research Training Program (to A.T.).

Abbreviations used

- AAA

ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities

- BS3

bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate

- CHMP

charged MVB protein

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- ESCRT

endosomal sorting complex required for transport

- FPLC

fast protein liquid chromatography

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IST1

increased sodium tolerance-1

- MIM

MIT-interacting motif

- MIT

present in microtubule-interacting and trafficking molecules

- MVB

multivesicular body

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E12-04-0292) on September 26, 2012.

REFERENCES

- Agromayor M, Carlton JG, Phelan JP, Matthews DR, Carlin LM, Ameer-Beg S, Bowers K, Martin-Serrano J. Essential role of hIST1 in cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1374–1387. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajorek M, Morita E, Skalicky JJ, Morham SG, Babst M, Sundquist WI. Biochemical analyses of human IST1 and its function in cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009a;20:1360–1373. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajorek M, Schubert HL, McCullough J, Langelier C, Eckert DM, Stubblefield WM, Uter NT, Myszka DG, Hill CP, Sundquist WI. Structural basis for ESCRT-III protein autoinhibition. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009b;16:754–762. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone C. Cellular pathways of hereditary spastic paraplegia. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:25–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballe A, Martin-Serrano J. ESCRT machinery and cytokinesis: the road to daughter cell separation. Traffic. 2011;12:1318–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell JW, Lindon C, Luzio JP, Reid E. Spastin couples microtubule severing to membrane traffic in completion of cytokinesis and secretion. Traffic. 2009;10:42–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimaano C, Jones CB, Hanono A, Curtiss M, Babst M. Ist1 regulates Vps4 localization and assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:465–474. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbro M, et al. Cdk1/Erk2- and Plk1-dependent phosphorylation of a centrosome protein, Cep55, is required for its recruitment to midbody and cytokinesis. Dev Cell. 2005;9:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrus JE, et al. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell. 2001;107:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizetti J, Gerlich DW. ESCRT-III polymers in membrane neck constriction. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson PI, Roth R, Lin Y, Heuser JE. Plasma membrane deformation by circular arrays of ESCRT-III protein filaments. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:389–402. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD. The ESCRT pathway. Dev Cell. 2011;21:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CP, Babst M. Structure and function of the membrane deformation ATPase Vps4. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JH. The ESCRT complexes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45:463–487. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.502516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JH, Hanson PI. Membrane budding and scission by the ESCRT machinery: it's all in the neck. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:556–566. doi: 10.1038/nrm2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lata S, Roessle M, Solomons J, Jamin M, Göttlinger HG, Svergun DI, Weissenhorn W. Structural basis for autoinhibition of ESCRT-III CHMP3. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:818–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-A, Beigneux A, Ahmad ST, Young SG, Gao F-B. ESCRT-III dysfunction causes autophagosome accumulation and neurodegeneration. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1561–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumb JH, Connell JW, Allison R, Reid E. The AAA ATPase spastin links microtubule severing to membrane modelling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita E. Differential requirements of mammalian ESCRTs in multivesicular body formation, virus budding and cell division. FEBS J. 2012;279:1399–1406. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita E, Sandrin V, Chung H-Y, Morham SG, Gygi SP, Rodesch CK, Sundquist WI. Human ESCRT and ALIX proteins interact with proteins of the midbody and function in cytokinesis. EMBO J. 2007;26:4215–4227. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller M, Adell MAY, Teis D. Membrane abscission: first glimpse at dynamic ESCRTs. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R603–R605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obita T, Saksena S, Ghazi-Tabatabai S, Gill DJ, Perisic O, Emr SD, Williams RL. Structural basis for selective recognition of ESCRT-III by the AAA ATPase Vps4. Nature. 2007;449:735–739. doi: 10.1038/nature06171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osako Y, Maemoto Y, Tanaka R, Suzuki H, Shibata H, Maki M. Autolytic activity of human calpain 7 is enhanced by ESCRT-III-related protein IST1 through MIT-MIM interaction. FEBS J. 2010;277:4412–4426. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Zhu P-P, Parker RL, Blackstone C. Hereditary spastic paraplegia proteins REEP1, spastin, and atlastin-1 coordinate microtubule interactions with the tubular ER network. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1097–1110. doi: 10.1172/JCI40979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renvoisé B, Parker RL, Yang D, Bakowska JC, Hurley JH, Blackstone C. SPG20 protein spartin is recruited to midbodies by ESCRT-III protein Ist1 and participates in cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3293–3303. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-10-0879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rismanchi N, Soderblom C, Stadler J, Zhu P-P, Blackstone C. Atlastin GTPases are required for Golgi apparatus and ER morphogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1591–1604. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O, Teis D. The ESCRT machinery. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R116–R120. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibinski G, et al. Mutations in the endosomal ESCRT III-complex subunit CHMP2B in frontotemporal dementia. Nat Genet. 2005;37:806–808. doi: 10.1038/ng1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuchell-Brereton MD, Skalicky JJ, Kieffer C, Karren MA, Ghaffarian S, Sundquist WI. ESCRT-III recognition by VPS4 ATPases. Nature. 2007;449:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature06172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang HTH, Connell JW, Brown SE, Thompson A, Reid E, Sanderson CM. A systematic analysis of human CHMP protein interactions: additional MIT domain-containing proteins bind to multiple components of the human ESCRT III complex. Genomics. 2006;88:333–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Rismanchi N, Renvoisé B, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Blackstone C, Hurley JH. Structural basis for midbody targeting of spastin by the ESCRT-III protein CHMP1B. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1278–1286. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P-P, Patterson A, Lavoie B, Stadler J, Shoeb M, Patel R, Blackstone C. Cellular localization, oligomerization, and membrane association of the hereditary spastic paraplegia 3A (SPG3A) protein atlastin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49063–49071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P-P, Patterson A, Stadler J, Seeburg DP, Sheng M, Blackstone C. Intra- and intermolecular domain interactions of the C-terminal GTPase effector domain of the multimeric dynamin-like GTPase Drp1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35967–35974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.