Abstract

The mechanisms by which glucose regulates the activity of glucose-inhibited (GI) neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) are largely unknown. We have previously shown that AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) increases nitric oxide (NO) production in VMH GI neurons. We hypothesized that AMPK-mediated NO signaling is required for depolarization of VMH GI neurons in response to decreased glucose. In support of our hypothesis, inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) or the NO receptor soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) blocked depolarization of GI neurons to decreased glucose from 2.5 to 0.7 mM or to AMPK activation. Conversely, activation of sGC or the cell-permeable analog of cGMP, 8-bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cGMP), enhanced the response of GI neurons to decreased glucose, suggesting that stimulation of NO-sGC-cGMP signaling by AMPK is required for glucose sensing in GI neurons. Interestingly, the AMPK inhibitor compound C completely blocked the effect of sGC activation or 8-Br-cGMP, and 8-Br-cGMP increased VMH AMPKα2 phosphorylation. These data suggest that NO, in turn, amplifies AMPK activation in GI neurons. Finally, inhibition of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) Cl− conductance blocked depolarization of GI neurons to decreased glucose or AMPK activation, whereas decreased glucose, AMPK activation, and 8-Br-cGMP increased VMH CFTR phosphorylation. We conclude that decreased glucose triggers the following sequence of events leading to depolarization in VMH GI neurons: AMPK activation, nNOS phosphorylation, NO production, and stimulation of sGC-cGMP signaling, which amplifies AMPK activation and leads to closure of the CFTR.

Keywords: soluble guanylyl cyclase; guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate; cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator; glucose-sensing neurons; membrane potential sensitive dye

the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), which contains the arcuate and ventromedial (VMN) nuclei, is critical for regulating energy and glucose homeostasis (22). Within the VMH, specialized glucose-sensing neurons change their electrical activity in response to changes in extracellular glucose concentration (16, 24, 28). Glucose-excited (GE) neurons increase, whereas glucose-inhibited (GI) neurons decrease, their action potential frequency as glucose levels rise (23). Like the pancreatic β-cell, the ATP-sensitive K+ channel mediates glucose sensing in VMH GE neurons (23, 28). Less is known about the ion channel involved in glucose sensing by GI neurons; however, our previous data suggest that glucose inhibits VMH GI neurons via the activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) Cl− conductance (9, 23).

The cellular fuel sensor 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) confers glucose sensitivity to VMH GI neurons (5, 16, 18). Fuel deficit increases the AMP-to-ATP ratio and activates AMPK (13). Depolarization of VMH GI neurons by decreased glucose is mimicked by the AMPK activator 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside (AICAR) and blocked by the AMPK inhibitor compound C (5, 16, 18). Moreover, AMPK activation mediates the fasting-induced increase in the response of VMH GI neurons to decreased glucose (18). Thus the level of AMPK activation is a critical determinant of glucose sensitivity in VMH GI neurons. However, the downstream signaling pathway by which AMPK regulates glucose sensing in GI neurons is unclear.

It is well established that AMPK inhibits the CFTR in a variety of cells (11, 26). This is consistent with our observations that decreased glucose depolarizes GI neurons by inhibiting a Cl− channel. This Cl− channel is likely to be the CFTR (9). Decreased glucose and AMPK activation also increase the production of the gaseous neurotransmitter nitric oxide (NO) by neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) in VMH GI neurons (5). Cultured VMH neurons from hyperglycemic rats neither increase NO production nor depolarize in response to decreased glucose. AMPK activation restored NO production in these neurons (4). These data suggest that NO may mediate the effects of AMPK in VMH GI neurons. Many of the effects of NO are mediated by activation of the NO receptor soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) and the production of guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) (3, 12). An elegant study by Lira et al. (14) demonstrated that activation of the NO-sGC-cGMP pathway caused an amplification of AMPK activity that was necessary for AMPK-mediated changes in glucose transporter GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle cells. Thus the present study tests the hypothesis that a similar interaction between AMPK and NO via the sGC-cGMP signaling pathway is required for inhibition of the CFTR and depolarization of VMH GI neurons in response to decreased glucose. This hypothesis was tested using cultured VMH neurons stained with membrane potential-sensitive dye, electrophysiological recordings of GI neurons in brain slices, and VMH immunoblots for phosphorylated AMPKα2, nNOS, and CFTR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male, 4- to 6-wk-old C57/BL6 mice (Taconic Laboratories, Germantown, NY) or Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on 0700–1900). Animals were weaned at 21 days of age and tested at 4–6 wk of age. Standard rodent chow (Purina 5001) and water were provided ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the New Jersey Medical School.

Preparation of Cultured Neurons

On the day of the experiment, C57/BL6 mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) and then transcardially perfused with ice-cold oxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) perfusion solution composed of the following (in mM): 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 7 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 28 NaHCO3, 7 glucose, 1 ascorbate, and 3 pyruvate, pH 7.4, with osmolarity adjusted to ∼300 mosmol/kgH2O. Brains were removed and placed in slushy perfusion solution, and coronal hypothalamic sections (250–350 μm) containing the VMH were cut using a vibratome (Vibratome Series 1000 cutting system, St. Louis, MO). Hypothalamic sections were maintained at 34°C in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing 5 mM glucose (in mM: 127 NaCl, 1.9 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 1.3 MgCl2, and 2.4 CaCl2, pH 7.4, with osmolarity adjusted to ∼300 mosmol/kgH2O with sucrose) for 30 min. Slices were transferred to normal oxygenated room temperature aCSF (2.5 mM glucose) for an additional 30 min before dissociation.

As described previously (28), brain slices were placed in Hibernate A/B27 medium containing 2.5 mM glucose (Brainbits, Carlsbad, CA). The VMH was dissected and digested in Hibernate A with papain (final concentration 20 U/ml) for 30 min in a 37°C rotating platform water bath rotating at 100 rpm. The tissue was then rinsed with Hibernate A/B27 and subjected to gentle trituration. After trituration, the cell suspension was centrifuged and the pellet resuspended in growth medium (Neurobasal; Invitrogen, Springfield, IL). Neurons were plated in growth medium with Fluoresbrite beads and incubated in glucose levels seen in the brain of fed (2.5 mM) or fasted (0.7 mM) rats (7, 25, 26). The beads were used for later data normalization.

Measurement of Membrane Depolarization Using Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader Membrane Potential Dye

Neurons were visualized on an Olympus BX61 WI microscope with a ×10 objective equipped with a red filter for fluorometric imaging plate reader membrane potential dye (FLIPR-MPD) visualization (excitation, 548 nm; emission, 610–675 nm). FLIPR-MPD (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. Incubation of VMH neurons in 1.75% FLIPR-MPD at 37°C in extracellular solution (composition in mM: 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 2.5 glucose, pH 7.4) began 30 min before and continued throughout the duration of all experiments. Previous work showed that this concentration of FLIPR-MPD produced detectable fluorescence without causing toxicity (18).

Images were captured at 1-min intervals over the course of each experiment using a charge-coupled device camera (Cool Snap HQ; Photometrics). Images were acquired and analyzed using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging). The fluorescence intensity of each image (expressed as gray scale units per pixel) was normalized to that of the coincubated fluorescent beads. Images were captured both before and after the extracellular test conditions were changed. In experiments evaluating the effects of test compounds on the response to decreased glucose, the initial extracellular recording (or bath) solution containing 2.5 mM glucose was exchanged 5 min after initiation of image acquisition with an identical solution containing 0.7 mM glucose. In these experiments, the test compound was present in both the 2.5 and 0.7 mM glucose-containing solutions. For single compound experiments, VMH cultures were preexposed for 30 min in the specific test compound. For agonist-antagonist studies, neuronal cultures were first incubated with the antagonist [7-nitroindazole (7-NINA), 1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo(4,3-a)quinoxalin (ODQ), or compound C] followed by 30 min in a combination of antagonist and agonist [7-NINA/AICAR, ODQ/AICAR, CC/5-(1-(phenylmethyl)-H-indazol-3-yl)-2-furanmethanol (YC-1), ODQ/YC-1]. In experiments evaluating the effect of a given compound on the membrane potential of VMH GI neurons in the absence of changing glucose, the test compound was added to extracellular solution containing 2.5 mM glucose 5 min after initiation of image acquisition. Test compounds then remained in the extracellular fluid throughout the imaging procedure.

As described previously, an average percent change of >11% in FLIPR-MPD fluorescence intensity between 10 and 20 min post-glucose change [%ΔFLIPR-MPD (10–20)] defined a depolarized neuron (18). Cell viability was confirmed at the end of each experiment by a 5-min exposure to 200 μM glutamate; neurons were considered to be viable if glutamate exposure increased FLIPR-MPD fluorescent intensity by at least 20%. Only glutamate-responsive neurons were used. The percentage of depolarized neurons [%ΔFLIPR-MPD (10–20) >11%] per culture dish was recorded for each treatment.

Electrophysiological Recording

Brain slices containing the VMH were prepared from Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) as described for Preparation of cultured neurons. Slices (300 μm) were maintained in oxygenated aCSF. Viable neurons were visualized and studied under infrared differential-interference contrast microscopy with a Leica DMLFS microscope equipped with a ×40 long-working-distance water-immersion objective. Current-clamp recordings (standard whole cell recording configuration) from neurons in the VMN were performed using a MultiClamp 700A (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and analyzed using pCLAMP 9 software. During recording, brain slices were perfused at 10 ml/min with normal oxygenated aCSF. Borosilicate pipettes (1–3 MΩ; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) were filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM) 128 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 4 KOH, 10 HEPES, 4 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, and 2 Na2ATP, pH 7.2. Osmolarity was adjusted to 290–300 mosmol/kgH2O with sucrose. Input resistance (IR) was calculated from the change in membrane potential in response to small 500-ms hyperpolarizing pulses (−20 pA) given every 3 s. Junction potential between the bath and the patch pipette was nulled before the formation of a gigaohm seal. Membrane potential and action potential frequency were allowed to stabilize for 10–15 min after the formation of a gigaohm seal. Neurons whose access resistance exceeded 20 MΩ were rejected. The membrane response was measured only after membrane potential and action potential frequency stabilized following each treatment. This value was compared with controls measured immediately before treatment. Extracellular glucose levels were altered and chemicals added as indicated.

CFTR Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis for Phosphorylated and Total nNOS, AMPK, and CFTR

CFTR immunoprecipitation.

VMH samples were lysed at 0°C in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaF, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.2 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 2 μg/ml aprotinin). Membrane fractions of whole cell lysate were obtained via repeated freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen and at 37°C. Lysates were precleared with Pansorbin 10% (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), diluted in 1× RIPA buffer, and incubated with a polyclonal antibody against CFTR (1 μg/200 μl; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 12 h at 4°C, followed by pulldown with protein A/G Plus-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h at 4°C under constant agitation. Eluted protein is subjected to immunoblot analysis as stated below.

Immunoblotting of phosphorylated AMPK, nNOS, and CFTR.

VMH lysate as prepared above or immunoprecipitated lysate samples were electrophoresed and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Immunodetection with the following primary antibodies was performed for 12 h at 4°C: anti-nNOS (1:1,000; Millipore), anti-phospho-nNOS (1:1,000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-phospho-AMPKα (Thr172, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-AMPKα2 (1:1,000; Abcam), and anti-CFTR (1:1,000; Cell Signaling). CFTR phosphorylation was determined using the serine/threonine Omni-phos kit (1:1,000; Millipore). Visualization was performed using relevant secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and the SuperSignal Pico ECL kit (Thermo) and was quantified using Scion Image. Results are presented as percentages of control after normalization to glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) or total nNOS, AMPK, or CFTR where applicable.

Chemicals

The AMPK activator AICAR (0.5 mM; Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto, ON, Canada) and the cGMP analog 8-bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cGMP; 2 mM; Tocris, Ellisville, MO) were prepared in extracellular solution. The AMPK inhibitor compound C (10 μM; Calbiochem), the NOS inhibitors 7-NINA (10 μM; Tocris) and NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA; 0.1 mM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor ODQ (10 μM; Tocris), the guanylyl cyclase activator YC-1 (10 μM; Cayman Chemicals; Ann Arbor, MI), or the CFTR channel modulator gemfibrozil (20 μM; Sigma) were prepared as 1,000× stocks in DMSO. Stock solutions were diluted so that the final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1%. Initial studies showed that DMSO did not change FLIPR-MPD fluorescence under conditions of constant glucose and did not alter the number of detectable depolarized neurons observed with glucose concentration reduction.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test or a Student's t-test, with P < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

nNOS is Required for Depolarization of GI Neurons in Response to Decreased Glucose and AMPK Activation

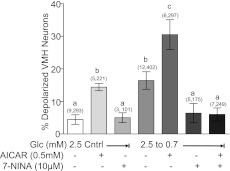

We have previously shown that a decrease in extracellular glucose concentration from 2.5 to 0.7 mM was the threshold glucose decrease required for detection of GI neurons using %ΔFLIPR-MPD (10–20) as an index of depolarization (18). An increase in the percentage of detectable GI neurons in response to this glucose decrease indicated increased responsiveness to decreased glucose, and conversely, a decrease in the percentage of GI neurons indicated impaired detection of decreased glucose. The maximal number of GI neurons was detected in response to decreased glucose from 2.5 to 0.5 mM or when glucose was decreased from 2.5 to 0.7 mM in the presence of AICAR (18). The experimental manipulations in the current study are based on these previous results. The effects of the nNOS inhibitor 7-NINA on the number of VMH neurons that increased their FLIPR-MPD fluorescence in response to decreased glucose from 2.5 to 0.7 mM or AICAR are shown in Fig. 1. As we showed previously (18), AICAR increased the percentage of GI neurons observed in 2.5 mM glucose to that observed when glucose was lowered from 2.5 to 0.7 mM. A further increase in the percentage of GI neurons was observed when AICAR was combined with decreased glucose from 2.5 to 0.7 mM. 7-NINA alone did not change the number of GI neurons detected in 2.5 mM glucose (P > 0.05). However, 7-NINA reduced the number of VMH GI neurons detected as glucose was reduced from 2.5 to 0.7 mM in the presence and absence of AICAR to background levels (Fig. 1; P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of depolarized neurons in ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) cultures from mice. In 2.5 mM glucose, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside (AICAR) increased whereas 7-nitroindazole (7-NINA) did not change the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons. Decreasing glucose from 2.5 to 0.7 mM increased the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons. Decreasing glucose in the presence of AICAR significantly increased the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons compared with that observed when glucose was decreased alone. 7-NINA inhibited the effect of decreasing glucose on depolarization of VMH neurons in the presence or absence of AICAR. Glc, glucose. Data are means ± SE and show the percentage of glucose-inhibited (GI) neurons per culture dish. The number of dishes used and number of cells analyzed are shown in parentheses above each bar (no. of dishes, no. of cells). Each dish comprised cells pooled from at least 3 mice. a,b,cP < 0.05, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other.

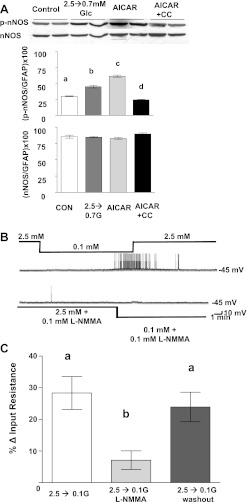

Immunoblots of VMH tissue using a specific mouse phospho-nNOS antibody showed that both decreasing glucose from 2.5 to 0.7 mM or the presence of AICAR in 2.5 mM glucose significantly increased the level of nNOS phosphorylation (Fig. 2A; P < 0.001). Because AICAR is known to have non-AMPK-mediated effects (19), AICAR was coapplied with compound C to confirm that increases in nNOS phosphorylation were mediated specifically via AMPK activation. Compound C reversed the increase in nNOS phosphorylation seen in the presence of AICAR (Fig. 2A). Total nNOS (Fig. 2A) and GFAP levels (data not shown) were unaffected by any of the above treatments.

Fig. 2.

A: a representative immunoblot (top) of phosphorylated neuronal nitric oxide synthase (p-nNOS) and total nNOS performed on hypothalamic slices containing the VMH from mice. Both reducing glucose to 0.7 mM or adding AICAR (0.5 mM) to 2.5 mM glucose increased nNOS phosphorylation compared with control tissue tested in 2.5 mM glucose. There was no change in nNOS phosphorylation of tissue cotreated with AICAR (0.5 mM) and compound C (CC; 30 μM). Total nNOS levels were the same in all treatment groups. Each lane contains VMH from an individual mouse. Immunoblots of p-nNOS and total nNOS (bottom) were measured using densitometry and quantitated relative to glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) levels (n = 6). a,b,c,dP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other. B: consecutive current-clamp recordings from a VMH GI neuron in a brain slice from a rat. Resting membrane potential is noted at right of each trace. Downward deflections represent the membrane voltage response to a constant hyperpolarizing pulse. The membrane voltage response is directly proportional to the change in input resistance (IR). Decreasing extracellular glucose levels from 2.5 to 0.1 mM causes hyperpolarization, decreased IR, and decreased action potential frequency (top trace). The NOS inhibitor NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA) blocked the response to decreased glucose (bottom trace). C: IR of VMH GI neurons in brain slices from rats (n = 15). Decreasing glucose from 2.5 to 0.1 mM significantly increased the IR of GI neurons; this was blocked by l-NMMA. The effect of l-NMMA was reversed on washout. **P < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other (1-way repeated-measures ANOVA within the same neuron).

We next confirmed our results using FLIPR-MPD with patch-clamp recordings of VMH GI neurons in brain slices, the gold standard method for evaluation of the glucose sensitivity of VMH GI neurons (9, 23–25). Figure 2B shows that the nonspecific NOS inhibitor l-NMMA (0.1 mM) blocked depolarization and increased action potential frequency of a GI neuron in response to decreased glucose. Furthermore, the increase in input resistance in response to decreased glucose from 2.5 to 0.1 mM was reduced from 28 ± 5 to 7 ± 3% in the presence of 0.1 mM l-NMMA (P < 0.01; Fig. 2C). The effect of l-NMMA was completely reversed by washout (Fig. 2C). Thus data obtained using FLIPR-MPD in cultured VMH neurons, patch clamp recordings of VMH GI neurons and immunoblots of VMH nNOS phosphorylation all indicate that nNOS activation is required for GI neurons to depolarize in response to decreased glucose or AMPK activation.

sGC-cGMP Signaling Pathway is Required for Depolarization of VMH GI Neurons in Response to AICAR and Decreased Glucose

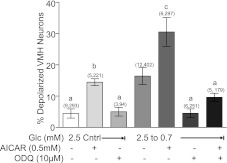

The number of GI neurons detected in VMH cultures as glucose was decreased from 2.5 to 0.7 mM was reduced in the presence of the sGC inhibitor ODQ (Fig. 3 ; P < 0.05). ODQ (10 μM) did not change the number of GI neurons detected in 2.5 mM glucose (Fig. 3; P > 0.05). Moreover, ODQ blocked depolarization of GI neurons in response to decreased glucose in the presence of AICAR (Fig. 3; P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of depolarized neurons in VMH cultures from mice. AICAR increased whereas ODQ did not change the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons observed in 2.5 mM glucose. Decreasing glucose from 2.5 to 0.7 mM increased the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons. AICAR significantly increased the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons observed in response to decreased glucose. ODQ inhibited the effect of decreasing glucose on VMH neuron depolarization in the presence and absence of AICAR. Data are means ± SE and show the percentage of GI neurons per culture dish. The number of dishes used and number of cells analyzed are shown in parentheses above each bar (no. of dishes, no. of cells). Each dish comprised cells pooled from at least 3 mice. a,b,cP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other. Note that the data shown in the second, fourth, and fifth bars are identical to those shown in Fig. 1 and are repeated to aid in visualizing the effects of ODQ.

In contrast to the sGC inhibitor ODQ, incubating VMH neurons with the sGC activator YC-1 (10 μM) increased the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons in 2.5 mM glucose (Fig. 4 ; P < 0.001). Furthermore, reducing glucose in the presence of YC-1 significantly increased the number of detectable GI neurons compared with reducing glucose alone (Fig. 4; P < 0.01) Compound C blocked the effect of reduced glucose on the depolarization of GI neurons in the presence and absence of YC-1 (P < 0.01).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of depolarized neurons in VMH cultures from mice. 5-(1-(Phenylmethyl)-H-indazol-3-yl)-2-furanmethanol (YC-1) significantly increased the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons, whereas compound C (Cmpd C) had no effect in 2.5 mM glucose. YC-1 significantly increased the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons observed when glucose was reduced from 2.5 to 0.7 mM. Cmpd C reversed the effect of reduced glucose on VMH neurons both in the presence and absence of YC-1. Data are means ± SE and show the percentage of GI neurons per culture dish. The number of dishes used and number of cells analyzed are shown in parentheses above each bar (no. of dishes, no. of cells). Each dish comprised cells pooled from at least 3 mice. a,b,c,dP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other.

The addition of the cell-permeable cGMP analog 8-Br-cGMP (2 mM) in 2.5 mM glucose significantly increased the number of depolarized GI neurons (Fig. 5 ; P < 0.01). Moreover, reducing glucose in the presence of 8-Br-cGMP significantly increased the number of depolarized GI neurons above that seen with 8-Br-cGMP or decreased glucose alone (Fig. 5; P < 0.01). Compound C blocked the effect of decreasing glucose in the presence of 8-Br-cGMP (Fig. 5; P < 0.01). The number of depolarized GI neurons observed when 8-Br-cGMP was added to 2.5 mM glucose was the same in the presence and absence of ODQ (+ODQ: 19 ± 3%, 7 dishes, 310 cells; −ODQ: 15 ± 4%, 5 dishes, 240 cells, P > 0.05), confirming that ODQ was acting via sGC inhibition. Finally, immunoblots of VMH tissue showed that both YC-1 and 8-Br-cGMP increased AMPK α2-subunit phosphorylation (Fig. 6 ; P < 0.01).

Fig. 5.

Percentage of depolarized neurons in VMH cultures from mice. 8-Bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cGMP) significantly increased the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons in 2.5 mM glucose as well as when glucose was reduced from 2.5 to 0.7 mM. This was completely blocked by Cmpd C. Data are means ± SE and show the percentage of GI neurons per culture dish. The number of dishes used and number of cells analyzed are shown in parentheses above each bar (no. of dishes, no. of cells). Each dish comprised cells pooled from at least 3 mice. a,b,cP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other.

Fig. 6.

A representative immunoblot of phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase α2-subunit (pAMPKα2) and total AMPKα2 performed on hypothalamic slices containing the VMH from mice. In 2.5 mM glucose, both 8-Br-cGMP (2 mM) and YC-1 (10 μM) increased AMPK phosphorylation compared with untreated control tissue. There was no difference in total AMPK levels between treatment groups. Each lane contains VMH from an individual mouse. Immunoblots (n = 6) of pAMPK (B) and total AMPK (C) were measured using densitometry and quantitated relative to GFAP levels. a,bP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other.

CFTR Cl− Conductance is a Downstream Target of AMPK-NO Signaling in VMH GI Neurons

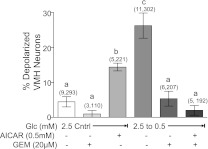

Gemfibrozil binds specifically to the CFTR (27). Using patch-clamp recordings, we previously have shown that gemfibrozil prevents Cl− channel closure in response to decreased glucose (9). In the present study, we show that gemfibrozil blocked the effect of decreased glucose from 2.5 to 0.5 mM in the presence and absence of AICAR (Fig. 7 ; P < 0.01). Gemfibrozil did not change the percentage of depolarized VMH neurons in 2.5 mM glucose (Fig. 7). The maximal glucose decrease used in the present study illustrates that gemfibrozil completely blocks detection of all VMH GI neurons.

Fig. 7.

Percentage of depolarized neurons in VMH cultures from mice. Gemfibrozil (Gem) had no effect on VMH neurons in 2.5 mM glucose; however, gemfibrozil inhibited depolarization in response to decreased glucose from 2.5 to 0.5 mM in the presence and absence of AICAR. Data are means ± SE and show the percentage of GI neurons per culture dish. The number of dishes used and number of cells analyzed are shown in parentheses above each bar (no. of dishes, no. of cells). a,b,cP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other.

Immunoblots of VMH tissue show that decreased glucose increases CFTR phosphorylation (Fig. 8A ; P < 0.001). AMPK inhibition with compound C inhibited the effect of decreased glucose on CFTR phosphorylation (Fig. 8A; P < 0.01). In contrast, AICAR in 2.5 mM glucose increased CFTR phosphorylation (Fig. 8A; P < 0.01). 8-Br-cGMP also increases CFTR phosphorylation in VMH tissue, and this was blocked by compound C (Fig. 8B; P < 0.001). Neither decreasing glucose nor 8-Br-cGMP affected the level of total CFTR (Fig. 7, A and B). Finally, nNOS inhibition with 7-NINA significantly inhibited CFTR phosphorylation in response to deceased glucose (Fig. 8C; P < 0.01). 7-NINA did not affect the level of total CFTR.

Fig. 8.

Representative immunoblots of phosphorylated cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (pCFTR) and total CFTR performed on hypothalamic slices containing the VMH from mice. A: reducing glucose (G) from 2.5 to 0.7 mM increased CFTR phosphorylation. Application of CC (30 μM) inhibited the effect of decreased glucose on CFTR phosphorylation, whereas AICAR (0.5 mM) stimulated CFTR phosphorylation. There was no difference in total CFTR levels between treatment groups. Each lane contains VMH from an individual mouse. Immunoblots of pCFTR were measured using densitometry, and pCFTR was quantitated relative to total CFTR levels. a,b,c,dP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other. B: 8-Br-cGMP (2 mM) in 2.5 mM glucose increased CFTR phosphorylation. Coapplication of CC (30 μM) inhibited the effect of 8-Br-cGMP on CFTR phosphorylation. There was no difference in total CFTR levels between treatment groups. Each lane contains VMH from an individual mouse. Immunoblots of pCFTR were measured using densitometry and quantitated relative to total CFTR levels. a,b,cP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other. C: reducing glucose increased CFTR phosphorylation. Reducing glucose in the presence of 7-NINA inhibited the effect of decreasing glucose on CFTR phosphorylation. There was no difference in total CFTR levels between treatment groups. Each lane contains VMH from an individual mouse. Immunoblots of pCFTR and total CFTR were measured using densitometry and quantitated relative to total CFTR levels. a,b,cP < 0.01, bars with different letters represent values statistically different from each other.

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that NO production and activation of the sGC-cGMP signaling pathway by AMPK, in turn, increases AMPK activity. This NO-sGC-cGMP-mediated amplification of AMPK activity is required for depolarization of VMH GI neurons in response to decreased glucose. Furthermore, our data support our hypothesis that GI neurons depolarize as a result of closure of the CFTR Cl− conductance. We (18) recently showed that the response of VMH GI neurons to decreased glucose is enhanced after fasting. In contrast, the response of VMH GI neurons to decreased glucose is reduced under conditions where central hypoglycemia detection is impaired (15, 25). Thus VMH GI neurons may play a key role in the detection of energy deficit (e.g., fasting, hypoglycemia) and initiation of compensatory mechanisms. The signaling cascade mediating the interaction between AMPK and NO is a possible therapeutic target for restoring normal glucose sensitivity to GI neurons under conditions where it is impaired (e.g., following recurrent insulin-hypoglycemia).

These studies were based on the work of Lira et al. (14) in skeletal muscle cells as well as our own studies (5) implicating AMPK and NO in glucose sensing in VMH GI neurons. Our previous studies (5) showed that AMPK phosphorylates nNOS and increases NO production in VMH GI neurons in response to decreased glucose. AMPK also phosphorylates and activates nNOS in skeletal muscle (6). Lira et al. (14) then showed that the NO donor S-nitroso-N-penicillamine (SNAP) increases GLUT4 mRNA expression and that AMPK inhibition blocked this effect. These data pointed to an amplification of AMPK activity by NO in skeletal muscle cells. We hypothesized that a similar interaction occurred in VMH GI neurons. The data from the present study strongly support this hypothesis.

First, we have extended our earlier findings by showing that nNOS activation by AMPK is required for depolarization of VMH GI neurons in response to decreased glucose. This conclusion is strengthened by the consistency between data obtained from patch-clamp recordings of VMH GI neurons in brain slices, membrane potential dye imaging in cultured VMH neurons, and immunoblots of VMH tissue. Such consistency in results is important due to the limitations of each technique. Patch-clamp recording of VMH GI neurons directly monitors the changes in electrical activity and cellular resistance. The fact that the cells remain “in situ,” at least with respect to their immediate interactions with adjacent cells, is also a plus. However, it is always possible that these interactions influence the results. A benefit of the membrane potential dye imaging technique is that we are able to screen much larger populations of neurons than with electrophysiology. On the other hand, we have thus far been unable to measure a concentration-response relationship using this technique. Therefore, we must quantify our responses as the number of cells responding. The current data are consistent with our previous work (18) showing that the number of depolarized (GI) neurons in response to a maximal stimulus does not change and lend confidence to the results. Finally, immunoblots of VMH tissue verify the cellular target of the various pharmacological agents. However, single-cell resolution is not possible. Thus, although there are limitations of each technique used in the present study, the results taken together provide strong support for our hypotheses.

Our data also show that the sGC-cGMP signaling pathway mediates the effect of NO on GI neurons. Both the sGC activator YC-1 and the cGMP analog 8-Br-cGMP depolarize GI neurons and enhance their response to decreased glucose. On the other hand, inhibition of sGC with ODQ blocks depolarization of GI neurons in response to decreased glucose or AICAR. Thus decreased glucose activates AMPK, which then increases NO production via nNOS activation. NO binds to its receptor, sGC, leading to cGMP production. cGMP ultimately leads to closure of the CFTR Cl− conductance and depolarization in VMH GI neurons.

The effects of YC-1 and 8-Br-cGMP on depolarization of GI neurons in response to decreased glucose are completely blocked by the AMPK inhibitor compound C. Moreover, YC-1 and 8-Br-cGMP increase VMH AMPKα2 phosphorylation. Because YC-1 and 8-Br-cGMP also act downstream of AMPK and nNOS, these data clearly suggest that, as Lira et al. (14) found in skeletal muscle, the NO-sGC-cGMP pathway also increases AMPK activation in response to decreased glucose in VMH GI neurons. This amplification of AMPK by NO signaling may explain the exponential relationship between glucose concentration change and neuronal excitability of GI neurons we found using patch-clamp recordings (24). Similar signaling pathways in both skeletal muscle and GI neurons suggest that other signaling pathways used by skeletal muscle also may be applicable in GI neurons.

The question then arises as to how the NO-sGC-cGMP pathway regulates AMPK activity and apparently primes this enzyme to respond to energy deficit. It is well established that phosphorylation by upstream kinases [e.g., LKB-1 or calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKKβ)] is necessary for AMPK activation in skeletal muscle and neurons (13, 30). Moreover, our observation that nNOS inhibition blocks the effect of AMPK activation with AICAR suggests that cGMP activates an upstream kinase of AMPK. This is consistent with Lira et al. (14), who found that nNOS inhibition blocked AICAR-induced GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle. A recent study by Zhang et al. (31) clearly demonstrated that NO-induced AMPK phosphorylation in endothelial cells required CAMKKβ. Thus we speculate that NO-sGC-cGMP signaling activates CAMKKβ in VMH GI neurons.

It is important to note that in addition to the sGC-cGMP signaling pathway, NO also can activate AMPK through its effects on intracellular ATP levels and the generation of reactive oxygen species. For instance, NO reduces intracellular ATP levels through inhibition of creatinine kinase (10) and cytochrome c oxidase (7). However, AICAR activation of AMPK (13), as well as NO production (14) and depolarization of VMH-GI neurons (5), is independent of changes in intracellular energy status. Thus the requirement of nNOS activity for AICAR-induced GI neuronal depolarization argues that although NO may reduce intracellular ATP levels, a more direct effect of NO on AMPK also exists. Finally, NO production also causes the formation of reactive oxygen species such as peroxynitrite (ONOO−). ONOO− can activate AMPK independently of changes in cellular ATP levels (32). Hence, we cannot rule out this alternative mechanism for NO to activate AMPK in theses studies.

For many years we have known that decreased glucose inactivated a Cl− conductance to depolarize GI neurons; however, the identity of this Cl− conductance remained elusive (23, 24). We hypothesized that the CFTR Cl− conductance might play a role in glucose sensing in GI neurons, because it is the only metabolically sensitive Cl− conductance described in the literature (29). Furthermore, our recent electrophysiological data showing that gemfibrozil prevented inactivation of a Cl− conductance in GI neurons in response to decreased glucose supported this hypothesis (9). Our current data showing that gemfibrozil prevents depolarization of VMH GI neurons in response to decreased glucose or AICAR provide much stronger support that the CFTR Cl− conductance is the final target of AMPK activation in VMH GI neurons leading to depolarization.

Our data are consistent with studies showing that AMPK inactivates the CFTR in other tissues (11, 26). However, it must be noted that gemfibrozil has nonspecific effects. Gemfibrozil belongs to the family of clofibric acid analogs that are used to lower triglycerides (1). The mechanism underlying this effect is unclear but is unlikely to involve CFTR; that is, gemfibrozil inhibits hepatic palmitoyl CoA hydrolase (20) and activates both hepatic and cortical peroxisome proliferator and activator receptor-α (PPARα) (21). Moreover, although clofibric acid analogs do bind CFTR, they can either open or close the channel depending on enantiomer and tissue type (8). Our electrophysiology data indicating that the effects of gemfibrozil reverse at the Cl− equilibrium potential (9) and the literature suggesting that CFTR is the only Cl− channel associated with gemfibrozil (27) support our conclusions regarding the CFTR. Moreover, we have now shown that decreased glucose, AICAR, and 8-Br-cGMP phosphorylate the CFTR. The effects of decreased glucose and 8-Br-cGMP are blocked by nNOS and AMPK inhibition, respectively, further strengthening our conclusions. Finally, it has been shown that cGMP has AMPK-independent effects on the CFTR; however, these studies indicate that cGMP activates CFTR (2). Direct activation of CFTR by cGMP is not consistent with our results. Thus the most likely explanation for our results is that the sGC-cGMP pathway inhibits the CFTR via AMPK activation, although clearly further studies involving techniques such as small interfering RNA are needed to define the role of the CFTR in glucose sensing.

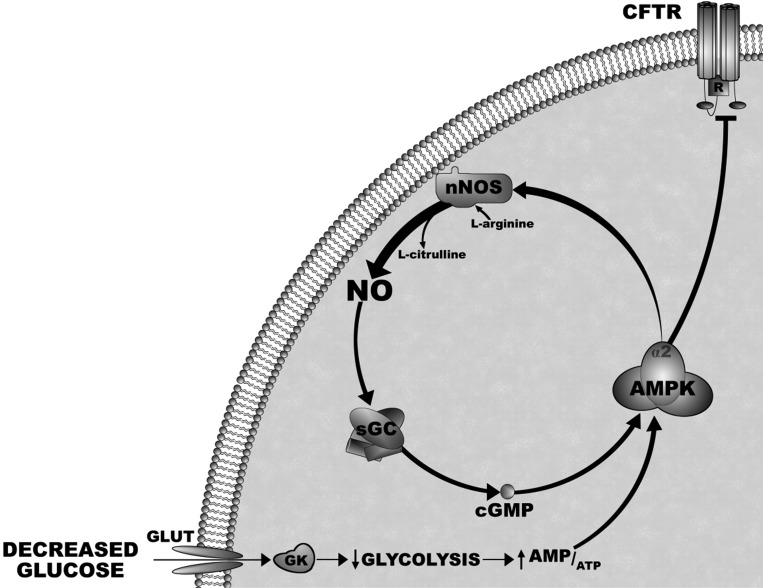

In summary, these data in combination with our previous findings provide strong evidence for the signal transduction pathway by which glucose regulates the activity of VMH GI neurons (Fig. 9) ; that is, decreased glucose activates AMPK. AMPK activation phosphorylates nNOS and increases NO production. NO binds to its receptor, sGC, and leads to cGMP production. cGMP increases the level of AMPK activation, possibly through an upstream kinase, and causes inactivation of the CFTR Cl− conduction. Closure of this Cl− conductance causes depolarization of GI neurons. We (9, 18) and others (17) have shown that GI neurons make up a significant percentage (∼40%) of the population of neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons in the arcuate nucleus. Moreover, the response of NPY-GI neurons to decreased glucose is enhanced following a fast (18). Conversely, the response of VMH GI neurons to decreased glucose is impaired under conditions where the ability of the brain to detect hypoglycemia is impaired (15, 25). Therefore, maintaining appropriate glucose sensitivity in VMH GI (and/or NPY-GI) neurons may be critical for the brain to detect and compensate for energy and/or glucose deficit. The AMPK-NO-AMPK signaling pathway is a putative therapeutic target for normalizing the glucose sensitivity of GI neurons under pathological conditions.

Fig. 9.

Diagram of the signaling pathway by which decreased glucose regulates action potential frequency of VMH GI neurons. Decreased extracellular glucose leads to decreased glucose uptake, metabolism, and ATP production, resulting in AMPK activation. AMPK activation phosphorylates nNOS and increases the production of NO via the conversion of l-arginine to l-citrulline. NO binds to its receptor, soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), and leads to cGMP production. cGMP increases the level of AMPK activation. This amplification of AMPK activity inactivates the CFTR Cl− conduction. Closure of this Cl− conductance causes depolarization of GI neurons and leads to neurotransmitter release. GK, glucokinase.

GRANTS

This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health Grants 2RO1 DK55619 (to V. H. Routh) and R21 HL089771 (to A. Beuve) and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Research Award 1-2007-13 (to V. H. Routh).

REFERENCES

- 1. Banks WA, Coon AB, Robinson SM, Moinuddin A, Shultz JM, Nakaoke R, Morley JE. Triglycerides induce leptin resistance at the blood-brain barrier. Diabetes 53: 1253–1260, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berger HA, Travis SM, Welsh MJ. Regulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel by specific protein kinases and protein phosphatases. J Biol Chem 268: 2037–2047, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boehning D, Snyder SH. Novel neural modulators. Annu Rev Neurosci 26: 105–131, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canabal DD, Potian JG, Duran RG, McArdle JJ, Routh VH. Hyperglycemia impairs glucose and insulin regulation of nitric oxide production in glucose-inhibited neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R592–R600, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canabal DD, Song Z, Potian JG, Beuve A, McArdle JJ, Routh VH. Glucose, insulin and leptin signaling pathways modulate nitric oxide synthesis in glucose-inhibited neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1418–R1428, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen ZP, McConell GK, Michell BJ, Snow RJ, Canny BJ, Kemp BE. AMPK signaling in contracting human skeletal muscle: acetyl-CoA carboxylase and NO synthase phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E1202–E1206, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cleeter MWJ, Cooper JM, rley-Usmar VM, Moncada S, Schapira AHV. Reversible inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, by nitric oxide: Implications for neurodegenerative diseases. FEBS Lett 345: 50–54, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conte-Camerino D, Mambrini M, DeLuca A, Tricarico D, Bryant S, Tortorella V, Bettoni G. Enantiomers of clofibric acid analogs have opposite actions on rat skeletal muscle chloride channels. Pflügers Arch 413: 105–107, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fioramonti X, Contie S, Song Z, Routh VH, Lorsignol A, Penicaud L. Characterization of glucosensing neuron subpopulations in the arcuate nucleus: Integration in NPY and POMC networks? Diabetes 56: 1219–1227, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gross WL, Bak MI, Ingwall JS, Arstall MA, Smith TW, Balligand JL, Kelly RA. Nitric oxide inhibits creatine kinase and regulates rat heart contractile reserve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 5604–5609, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hallows KR, Raghuram V, Kemp BE, Witters LA, Foskett JK. Inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by novel interaction with the metabolic sensor AMP-activated protein kinase. J Clin Invest 105: 1711–1721, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jaffrey SR, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a neural messenger. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 11: 417–440, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab 1: 15–25, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lira VA, Soltow QA, Long JH, Betters JL, Sellman JE, Criswell DS. Nitric oxide increases GLUT4 expression and regulates AMPK signaling in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1062–E1068, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCrimmon RJ, Song Z, Cheng H, McNay EC, Weikart-Yeckel C, Fan X, Routh VH, Sherwin RS. Corticotrophin-releasing factor receptors within the ventromedial hypothalamus regulate hypoglycemia-induced hormonal counterregulation. J Clin Invest 116: 1723–1730, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mountjoy PD, Bailey SJ, Rutter GA. Inhibition by glucose or leptin of hypothalamic neurons expressing neuropeptide Y requires changes in AMP-activated protein kinase activity. Diabetologia 50: 168–177, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muroya S, Yada T, Shioda S, Takigawa M. Glucose-sensitive neurons in the rat arcuate nucleus contain neuropeptide Y. Neurosci Lett 264: 113–116, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murphy BA, Fioramonti X, Jochnowitz N, Fakira K, Gagen K, Contie S, Lorsignol A, Penicaud L, Martin WJ, Routh VH. Fasting enhances the response of arcuate neuropeptide Y-glucose-inhibited (GI) neurons to decreased extracellular glucose. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C746–C756, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qin S, Ni M, De Vries GW. Implication of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase in inhibition of TNF-α- and IL-1β-induced expression of inflammatory mediators by AICAR in RPE cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49: 1274–1281, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sanchez R, Alegret M, Adzet T, Merlos M, Laguna J. Differential inhibition of long-chain acyl-CoA hydrolases by hypolipidemic drugs in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol 43: 639–644, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sanguino E, Ramon M, Roglans N, Alegret M, Sanchez RM, Vazquez-Carrera M, Laguna JC. Gemfibrozil increases the specific binding of rat-cortex nuclear extracts to a PPRE probe. Life Sci 73: 2927–2937, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 404: 661–671, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Song Z, Levin BE, McArdle JJ, Bakhos N, Routh VH. Convergence of pre- and postsynaptic influences on glucosensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Diabetes 50: 2673–2681, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Song Z, Routh VH. Differential effects of glucose and lactate on glucosensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Diabetes 54: 15–22, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Song Z, Routh VH. Recurrent hypoglycemia reduces the glucose sensitivity of glucose-inhibited neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus nucleus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R1283–R1287, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walker J, Jijon HB, Churchill T, Kulka M, Madsen KL. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase reduces cAMP-mediated epithelial chloride secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G850–G860, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walsh KB, Wang C. Effect of chloride channel blockers on the cardiac CFTR chloride and L-type calcium currents. Cardiovasc Res 32: 391–399, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang R, Liu X, Hentges ST, Dunn-Meynell AA, Levin BE, Wang W, Routh VH. The regulation of glucose-excited neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus by glucose and feeding-relevant peptides. Diabetes 53: 1959–1965, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winter MC, Sheppard DN, Carson MR, Welsh MJ. Effect of ATP concentration on CFTR Cl− channels: a kinetic analysis of channel regulation. Biophys J 66: 1398–1403, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Witczak C, Sharoff C, Goodyear L. AMP-activated protein kinase in skeletal muscle: from structure and localization to its role as a master regulator of cellular metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 3737–3755, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang J, Xie Z, Dong Y, Wang S, Liu C, Zou MH. Identification of nitric oxide as an endogenous activator of the AMP-activated protein kinase in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 283: 27452–27461, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32. Zou MH, Hou XY, Shi CM, Kirkpatick S, Liu F, Goldman MH, Cohen RA. Activation of 5′-AMP-activated kinase is mediated through c-Src and phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity during hypoxia-reoxygenation of bovine aortic endothelial cells: role of peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem 278: 34003–34010, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]