Abstract

The synthesis, comprehensive linear photophysical characterization, two-photon absorption (2PA), steady-state and time-resolved stimulated emission depletion properties of a new fluorene derivative, (E)-1-(2-(di-p-tolylamino)-9,9-diethyl-9H-fluoren-7-yl)-3-(thiophen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (1), are reported. The primary linear spectral properties, including excitation anisotropy, fluorescence lifetimes, and photostability, were investigated in a number of aprotic solvents at room temperature. The degenerate 2PA spectra of 1 were obtained with an open aperture Z-scan and two-photon induced fluorescence methods, using a 1-kHz femtosecond laser system, and maximum 2PA cross-sections of ~400–600 GM were obtained. The nature of the electronic absorption processes in 1 was investigated by DFT-based quantum chemical methods implemented in the Gaussian 09 program. The one- and two-photon stimulated emission spectra of 1 were measured over a broad spectral range using a femtosecond pump probe–based fluorescence quenching technique, while a new methodology for time-resolved fluorescence emission spectroscopy is proposed. An effective application of 1 in fluorescence bioimaging was demonstrated via one- and two-photon fluorescence microscopy images of HCT 116 cells containing the dye encapsulated micelles.

Keywords: fluorene derivatives, two-photon absorption, two-photon stimulated emission depletion, time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy, bioimaging

Introduction

The development of new organic molecules with efficient two-photon absorption (2PA) and stimulated emission depletion (STED) properties is a subject of enhanced scientific and technological interest for the manifold promising areas of nonlinear optical applications, such as 3D optical data storage and microfibrication,[1–4] two-photon–induced fluorescence microscopy (2PFM),[5, 6] two-photon optical power limiting,[7, 8] high-resolution molecular spectroscopy,[9] light amplification of stimulated emission,[10, 11] etc. Investigations of the electronic structure of organic molecules and the nature of their spontaneous and stimulated intramolecular vibronic transitions have allowed for the designing of efficient 2PA compounds with high fluorescence quantum yields and large STED cross-sections in the region of interest.[12–14] The strategy for the development of effective 2PA molecules and the corresponding experimental methods for 2PA cross-section determination are well established and widely used,[15–17] in contrast to STED spectroscopic techniques, which can be utilized in nonlinear-optical measurements.[18, 19] It is worth noting that stimulated emission processes in organic molecules have great potential for a number of the practical applications mentioned above and need to be investigated further. One of the promising methods among these investigations is a fluorescence-quenching methodology described previously by Lakowicz.[20, 21] This method is based on the quenching of fluorescence emission which can occur within a single excitation pulse, or can be accomplished by a separate time-delayed laser pulse with corresponding wavelength. This technique allows investigations of ultrafast processes occurring in the excited states of fluorophores,[22, 23] as well as the most accurate determination of corresponding one- and two-photon stimulated emission cross-sections using high intensity pico- and femtosecond laser pulses.[14, 24] Based on these data, one- and two-photon STED spectra can be evaluated for further development in some practical areas, such as high-resolution multiphoton fluorescence microscopy,[25, 26] upconverting lasing,[27, 28] superfluorescent labels for bioimaging,[29, 30] etc. Among the tremendous number of organic compounds with efficient nonlinear-optical properties, fluorene derivatives are promising organic structures with high potential for most of the known laser-based spectroscopic applications.[16, 31, 32]

In this paper, the STED properties of a new fluorene derivative, (E)-1-(2-(dip-tolylamino)-9,9-diethyl-9H-fluoren-7-yl)-3-(thiophen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (1), were investigated by a fluorescence-quenching femtosecond technique along with the comprehensive linear photophysical, photochemical, and 2PA characterizations of 1 in a broad variety of organic solvents at room temperature. Values of 2PA and stimulated-emission cross-sections of 1 were obtained in a broad spectral range with a 1-kHz tunable femtosecond laser system by open aperture Z-scan,[33] two-photon induced fluorescence (2PF),[34] and pump-probe fluorescence-quenching methods,[14] respectively. A time-resolved fluorescence spectrum method, based on STED pump-probe methodology, was proposed for the first time, and the values of the fast solvate relaxation constants for 1 in low viscosity media were evaluated. The nature of the electronic structure of 1 was also investigated using quantum-chemical calculations with DFT-based methods implemented in the Gaussian 09 program package.[35] High-fluorescence quantum yields, efficient 2PA and STED cross-sections, and good photochemical stability reveal the high potential of 1 for application in a number of important nonlinear-optical areas of use, including high-resolution STED microscopy.[25, 26] A high potential of 1 for application in bioimaging was shown via one- and two-photon fluorescence microscopy of epithelial colorectal carcinoma HCT 116 cells encapsulated in Pluronic® F-127 micelles.

Results and Discussion

Linear spectral and photochemical properties of 1

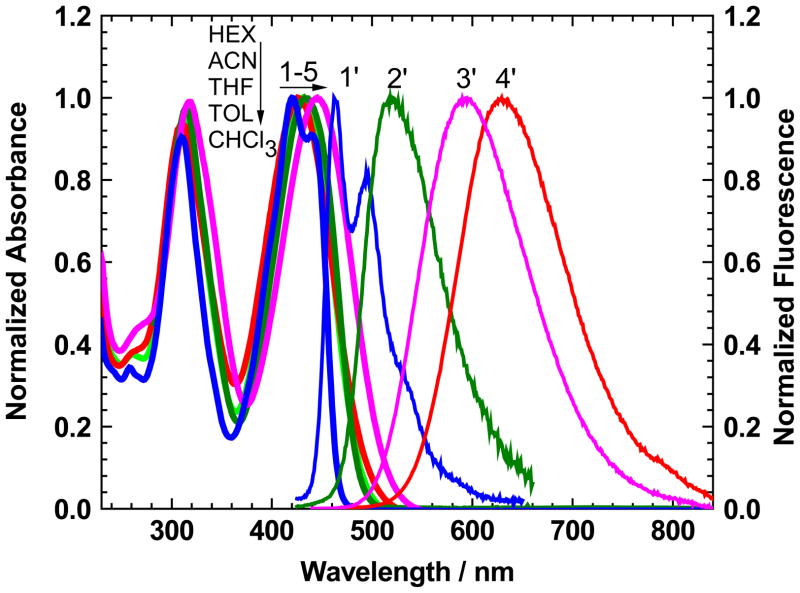

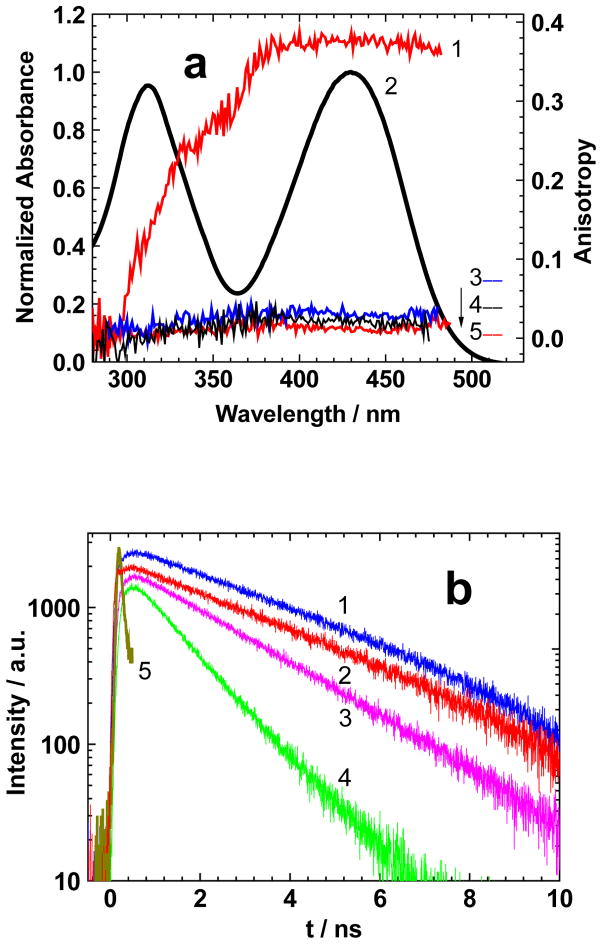

The linear absorption and fluorescence spectra of 1 in hexane (HEX), toluene (TOL), chloroform (CHCl3), tetrahydrofuran (THF), and acetonitrile (ACN), along with the main photophysical and photochemical parameters, are presented in Figure 1 and in Table 1, respectively. The steady-state absorption spectra exhibited a weak dependence on the solvent properties, and a structureless shape was observed in all of the investigated aprotic solvents, except for nonpolar HEX. Well-defined vibronic absorption peaks were observed in the main long-wavelength absorption band of 1 (360 – 480 nm) in HEX solutions (Figure 1, curve 1), with spacings associated with C-C vibrations (~ 1080 cm−1). The fluorescence spectra of 1 were independent of the excitation wavelength, λex in the whole absorption range and exhibited a strong solvatochromic behavior with a maximum Stokes shift greater than ~180 nm in CHCl3 (curve 4′). The values of fluorescence quantum yields, Φ, were sufficiently high (0.64 – 1.0) in all of the investigated solvents (except for polar ACN, see Table 1) and independent of λex in the spectral range 280 – 480 nm. These results were consistent with nice overlapping of the absorption and corrected excitation spectra of 1 in a broad spectral range. This finding implies a strict correspondence to Kasha’s rule,[36] which states that fluorescence transitions occur from the lowest excited state S1, and all other direct transitions Sn → S0 are negligible (S0 and Sn are the ground and a highly excited electronic state, respectively). The excitation anisotropy spectra of 1, r(λ), (Figure 2a, curves 1, 3–5) reveal the nature of the main long-wavelength absorption band. A constant value of anisotropy in the spectral range 380 nm ≤λex ≤ 470 nm corresponds to a single electronic transition S0 → S1, which is responsible for the main absorption band. In viscous polyTHF (pTHF), the maximum fundamental anisotropy value, r ≈ 0.38, is close to the theoretical limit,[36] which is indicative of nearly parallel orientation of the absorption, S0 → S1, and emission, S1 → S0, transition dipole moments, μ01 and μ10, respectively. Fluorescence emission processes in 1 exhibited a single exponential decay in all of the investigated solvents (Figure 2b), with corresponding lifetimes in the range 1 – 4 ns (Table 1). These values of fluorescence lifetimes, τ, were also calculated as: τcal = τR · Φ, where τR is the radiative lifetime obtained by the Strickler-Berg equation.[37] An acceptable correlation between experimental τ and calculated, τcal, lifetimes (presented in Table 1), along with a weak dependence of the steady-state absorption spectra on solvent polarity (Figure 1), are indicative of the absence of the strong specific solute-solvent interaction of 1 in the employed aprotic solvents. In the most polar ACN, a strong decrease in the fluorescence quantum yield was observed, and the experimental value of lifetime could not be determined with acceptable accuracy with the experimental equipment used. The values of rotational correlation time, θ≈ 190 ps, and the effective rotational volume of 1 in THF, V ≈ 160 Å3, were estimated from equation 2 (see Experimental Section) based on the assumption of equal values of the fundamental anisotropies, r0, of 1 in viscous pTHF and nonviscous THF and using fluorescence lifetimes and anisotropy data. The relatively fast rotation and small rotational volume of 1 allow for the assumption of the “in-plane” character of the molecular rotation and slipping boundary conditions in solute-solvent dynamics.[38] The processes of the photochemical decomposition of 1 exhibited the first order of the photochemical reaction in TOL, CHCl3 THF, and ACN, with corresponding quantum yields, Φph, in the range of ~ (1–4) · 10−5 (Table 1), which is of a sufficiently high level of molecular photostability for its practical applications. In nonpolar HEX, the value of Φph dramatically increased, and a complicated photochemical kinetic was observed. Detailed photochemical investigations were beyond the scope of this paper.

Figure 1.

Normalized steady-state absorption (1–5) and fluorescence (1′-4′) spectra of 1 in HEX (1, 1′), TOL (4, 2′), CHCl3 (5, 4′), THF (3, 3′), and ACN (2).

Table 1.

Main linear photophysical parameters of 1 in solvents with different polarity Δf and viscosity η: absorption, and fluorescence, , maxima, Stokes shifts, maxima extinction coefficients, εmax, fluorescence quantum yields, Φ, experimental, τ, and calculated, τcal, fluorescence lifetimes and photochemical decomposition quantum yields, Φph.

| N/N | HEX | TOL | CHCl3 | THF | ACN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δf[a] | 3·10−4 | 0.0135 | 0.148 | 0.209 | 0.305 |

| η, cP | 0.31 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.34 |

| , nm | 420 ±1 | 433 ±1 | 445 ±1 | 430 ±1 | 427 ±1 |

| , nm | 462 ±1 | 520 ±1 | 629 ±1 | 593 ±1 | 540 ±2 |

| Stokes shift, cm−1 (nm) | 2160 ±100 (42 ±2) | 3860 ±100 (87 ±2) | 6570 ±100 (184 ±2) | 6390 ±100 (163 ±2) | 4900 ±100 (113 ±6) |

| εmax *10−3, M−1cm−1 | 47 ±3 | 30 ±2 | 27 ±2 | 37 ±2 | 36 ±2 |

| Φ | 0.64 ±0.05 | 1.0 ±0.05 | 0.9 ±0.05 | 1.0 ±0.05 | 0.01 ±0.003 |

| τ, ns [b] | 1.15 ±0.08 | 2.3 ±0.08 | 3.5 ±0.08 | 3.8 ±0.08 | - |

| τcal, ns | 1.82 ±0.2 | 3.37 ±0.3 | 3.88 ±0.3 | 4.0 ±0.3 | 0.03 ±0.01 |

| Φph * 105 | 60 ±1 | 3 ±0.5 | 2.6 ±0.5 | 1.3 ±0.2 | 3.7 ±0.5 |

Orientation polarizability Δf = (ε − 1)/(2 ε + 1) − (n2 − 1)/(2n2 + 1) (ε and n are the dielectric constant and refraction index of the medium, respectively).

All experimental values of lifetimes were obtained with a goodness-of-fit parameters χ2 ≥ 0.99.

Figure 2.

(a) Excitation anisotropy spectra of 1 in pTHF (1), THF (5), TOL (3), HEX (4), and normalized absorbance in THF (2). (b) Fluorescence lifetime decay curves for 1 in THF (1), CHCl3 (2), TOL (3), HEX (4), and Instrument Response Function (5).

Quantum-chemical calculations

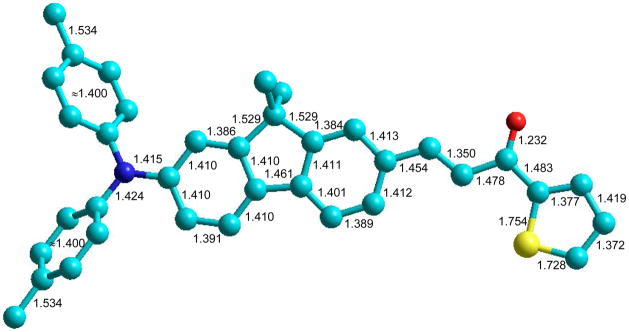

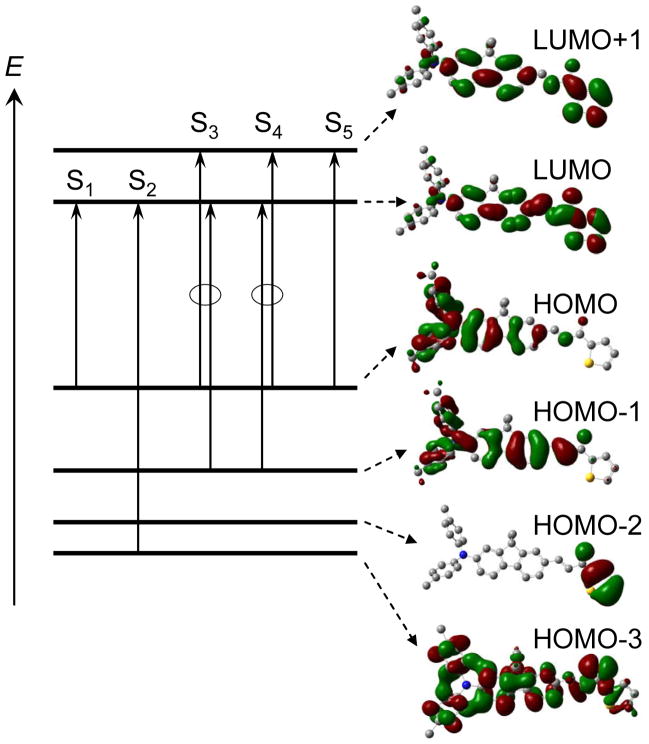

The optimized molecular geometry of 1 is presented in Figure 3 and reveals nearly equalized bond lengths of 1.40 ± 0.01 Å in all of the benzene rings, while the lengths of the bonds in the external chain show considerable alternation. As follows from these calculations, both phenyl substituents at the nitrogen atom are turned out at 44°; the rest of the optimized molecular structure is planar and exhibits sufficiently small rotational barriers (~ 2 kcal/mol) between fluorene moiety and whole external substituents. The values of oscillator strengths, fOS, main configurations and transition dipoles μij, (i = 0, 1; j = 2, 3, …) among the first 6 singlet electronic levels S0, S1, …, S5), along with the shape of the corresponding molecular orbitals (MO), are presented in Table 2 and Figure 4, respectively. As follows from the data in Figure 4, both phenyl substituents of the nitrogen atom do not take part in the LUMO and LUMO+1, whereas the thiophene ring contributes considerably in the lowest vacant MO. At the same time, the highest occupied MOs (HOMO and HOMO-1) are nearly insensitive to such chemical modifications of the fluorene moiety. The local orbital, HOMO-2, includes atoms of the thiophene ring only and does not participate in the main electronic transitions. The first electronic transition is described by one pure configuration and is connected with the long-wavelength band in the linear absorption, which is in good agreement with the steady-state (anisotropy spectrum (Figure 2a, curve 1). The calculated oscillator strength of the second transition (S0 → S2), fOS ≈ 0, and therefore, this transition cannot be observed in linear absorption. In contrast, the values of the oscillator strengths of the next two transitions S0 → S3 and S0 → S4 are sufficiently large and are comparable with the intensity of the main long-wavelength absorption band, which also reveals good correspondence between the calculated data and the observed short-wavelength absorption contour (Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Optimized molecular geometry of 1 obtained with the DFT/6–31(d,p)/B3LYP method (bond lengths in Å). Ethyl groups are replaced with CH3 for simplicity.

Table 2.

Calculated energies of the electronic transitions, Eij, oscillator strengths, fOS, and transition dipoles, μij, (i = 0, 1; j = 2, 3, …) of 1, (TDDFT/6–31(d,p)/B3LYP).

| Transition | Eij, eV | fOS | μij, D | Main configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 → S1 | 2.57 | 0.631 | 10.02 | 0.99 |HOMO→LUMO> |

| S0 → S2 | 3.21 | 0.000 | 0.0001 | 0.98 |HOMO3−→LUMO> |

| S0 → S3 | 3.58 | 0.735 | 7.34 | 0.90 |HOMO→LUMO+1> |

| −0.38 |HOMO− 1→LUMO> | ||||

| S0 → S4 | 3.69 | 0.269 | 4.37 | 0.40 |HOMO→LUMO+1> |

| +0.88 |HOMO−1→LUMO> | ||||

| S0 → S5 | 3.87 | 0.015 | 1.01 | 0.95 |HOMO→LUMO+1> |

| S1 → S2 | 0.64 | 0.043 | 4.22 | 0.98 |HOMO3−→HOMO> |

| S1 → S3 | 1.01 | 0.003 | 0.29 | 0.90 |LUMO→LUMO+1> |

| −0.38 |HOMO−1→HOMO> | ||||

| S1 → S4 | 1.12 | 0.623 | 12.08 | 0.40 |LUMO→LUMO+1> |

| +0.88 |HOMO−1→HOMO> | ||||

| S1 → S5 | 1.30 | 0.018 | 1.91 | 0.95 |LUMO→LUMO+1> |

Figure 4.

Main electronic transitions and corresponding molecular orbitals of 1.

2PA properties of 1

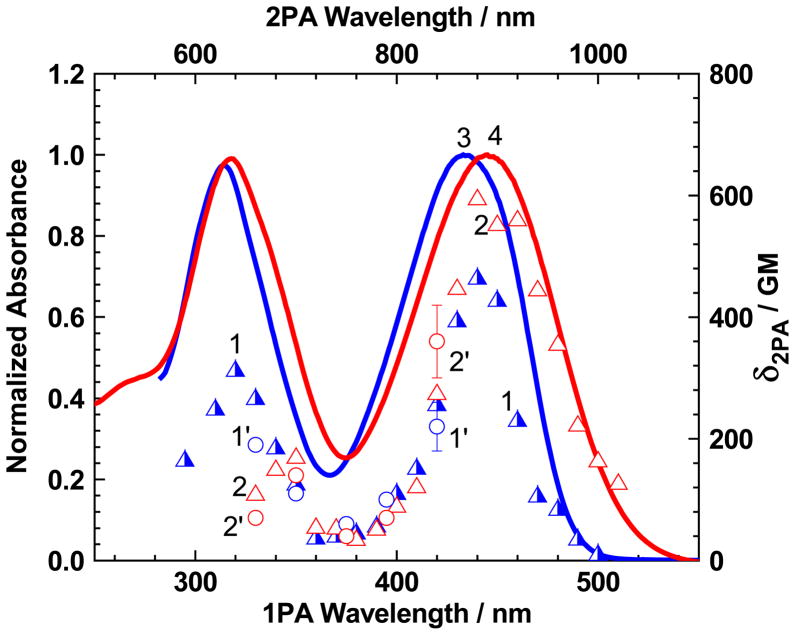

The degenerate 2PA spectra of 1 (Figure 5) were investigated in a broad spectral range (590–1020 nm), in solvents of different polarity by open aperture Z-scan[33] and 2PF[34] methods. A good agreement between the experimental 2PA cross-section values, δ2PA, obtained by two independent nonlinear optical methodologies was observed in the spectral range 660–840 nm. An unsymmetrical compound 1 exhibited two well-defined 2PA bands at λex ≈ 640–680 nm and 880–900 nm, with maximal cross-sections δ2PA ≈ 200–350 GM and 400–600 GM, respectively, and revealed a weak dependence of 2PA efficiency on solvent polarity. The shape of these spectra is typical for unsymmetrical fluorene derivatives,[39, 40] where a relatively strong2PA band overlaps with the main one-photon–allowed long-wavelength absorption contour. The nature of this band can be attributed to the possible changes in the stationary dipole moment of 1, Δμ01, under electronic excitation, S0 → S1, in accordance with the expression, based on simplified three-level model of 2PA processes:[41]

Figure 5.

Degenerate 2PA spectra of 1 in TOL (1, 1′) and CHCl3 (2, 2′), obtained by 2PF (1, 2 - triangles) and open-aperture Z-scan (1′, 2′ - circles) methods. Normalized linear absorption spectra of 1 in TOL (3) and CHCl3 (4).

| (1) |

where ; vex = c/λex; μ0f, and μ1f are the transition dipoles moments for S0 → Sf and S1 → Sf electronic transitions, respectively (Sf is the final electronic state); Δμ0f = μ00 − μff is the difference in the stationary dipole moments of the ground and final electronic states, respectively; Γ01 is the damping constant related to the transition frequency ; α and β are the angles between the vectors μ01, μ1 f and Δμ0 f, μ0 f, respectively; g(2vex) is the normalized Lorentzian shape function; and n is the refractive index of the medium. Eq. (1) is based on the sum over state (SOS) approach [42] and for 2PA excitation S0 → S1 gives δ2 PA ~ |Δμ01|2 |μ01|2 (1 + 2 cos2 α2) · g(2 νexc). The calculated values of the maximum 2PA cross-sections of 1, for the most intensive two-photon transitions S0 → S1, S0 → S2, and S0 → S4, are presented in Table 3. These cross-sections were obtained by eq. (1) using corresponding dipole moments from Table 2, calculating change in the stationary dipole moment of 1 under electronic excitation S0 → S1, Δμ01 ≈ 5.4 D, and damping constant Γ01 = 0.1 eV. As follows from the comparison of the experimental and calculated 2PA data, the best agreement is observed for S0 → S2 and S0 → S4 two-photon transitions. The noticeable difference between calculated and experimental 2PA cross-sections for S0 → S1 transition may be of concern with some underestimation of the change in the stationary dipole moments of 1.

Table 3.

Maximum values of calculated, , and experimental, δ2PA, 2PA cross sections of 1.

| Two-photon transition | , GM | δ2PA, GM |

|---|---|---|

| S0 →S1 | 120 | 400 – 600 |

| S0 →S2 | 90 | 50–100 |

| S0 →S4 | 300 | 200–350 |

A potential of 1 for practical application in 2PFM can be estimated based on Figure of Merit, FM = Φ · δ2PA/Φph, introduced previously in ref.[31] As follows from the data in Tables 1 and 3, the values of FM for compound 1 can be estimated as ~106 − 6·107, which are comparable with the best examples of the 2PA fluorescence labels.[43] High values of FM make fluorene derivative 1 a promising candidate for 2PFM applications using commercial femtosecond Ti:Sapphire lasers.

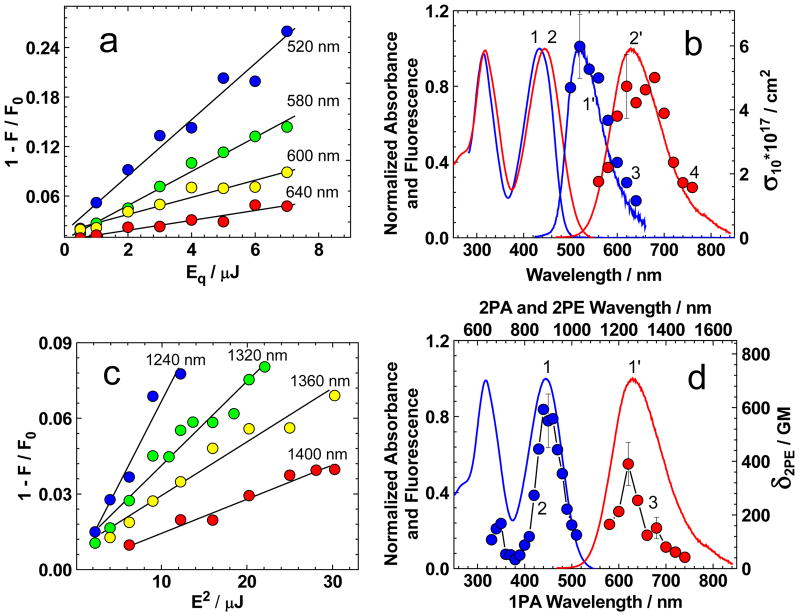

One- and two-photon STED spectra of 1

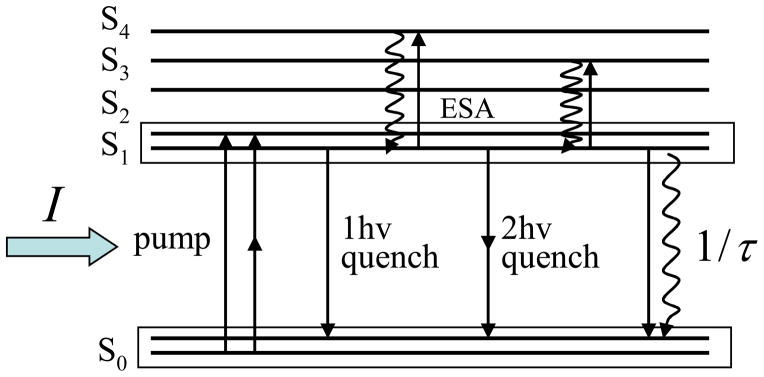

The steady-state and time-resolved STED spectra of 1 were investigated in TOL and CHCl3. A schematic diagram of the main spontaneous and stimulated transitions in 1 that occurred after electronic excitation is depicted in Figure 6. The values of one- and two-photon stimulated emission cross-sections (σ10 (λq) and σ2PE (λq), correspondingly) were obtained in a broad spectral range by a fluorescence quenching pump-probe method,[24] using femtosecond laser pulses. In the case of the steady-state STED measurements, a constant value of time delay between pump and probe beam, τD = 20 ps ≪ τ, was used, assuming that all excited state vibrational and solvate relaxation processes of 1 were finished in 20 ps, and after that, the observed STED spectra should be constant in time. The nature of STED processes for one- and two-photon stimulated emission transitions were determined from the experimental dependences 1 − IF/IF0 ~ σ10 (λq)· qEP and , presented in Figures 7a and 7c, respectively (IF and IF0 are the integral fluorescence intensities observed from one excitation pulse in the presence and absence of the quenching beam, correspondingly; λq is the quenching wavelength and qEP is the energy of the quenching pulse). Similar dependences were obtained for each quenching wavelength λq. A linear character of these dependences reveals the pure one- and two-photon nature of corresponding stimulated emission processes, occurring in 1 under the employed experimental conditions. The one-photon STED spectra of 1 in TOL and CHCl3 (Figure 7b, curves 3, 4) exhibited maximal cross-sections σ10 (λ) ~ (5–6) · 10−17 cm2 and were sufficiently close to the corresponding steady-state fluorescence contours (curves 1′, 2′). These maxima of σ10(λ) reveal small long-wavelength shifts ~10–20 nm relative to the maxima of fluorescence spectra, IF (λ), which is in good agreement with the theoretical prediction: σ10 (λ) ~ λ4· IF (λ).[44] It is worth mentioning that the absolute values of stimulated emission cross-sections σ10 (λ) exhibit sufficiently large deviation from the corresponding ground state absorption cross-sections, σ01 (λ) ≈ (1–1.2) · 10−16 cm2 (for 1 in TOL and CHCl3), which could be evidence of a strong influence of the solvate relaxation processes on the shape of the excited-state potential energy of 1. The two-photon STED spectrum of 1 was obtained only in CHCl3 (Figure 7d, curve 3), where the linear dependences were observed (Figure 7c). The maximum values of the two-photon stimulated emission cross-sections, , were less than the ground-state 2PA cross-sections, , and a small short wavelength shift of relative to the steady-state fluorescence contour was observed. It can be assumed that the nature of the two-photon STED spectrum of 1 is similar to the observed long-wavelength band in the 2PA spectrum (Figure 7d, curve 2) and is determined by the product: , where is the transition dipole of stimulated emission S1 → S0 and Δμ10 is the change in the corresponding stationary dipole moments of S1 and S0 electronic states, respectively. In TOL solution of 1, the efficiency of two-photon stimulated emission processes was not determined by the fluorescence quenching method due to the extremely low degree of two-photon fluorescence quenching. This result is not completely understandable and may be concerned with efficient ground-state three-photon absorption at ~1300 nm, which, in part, compensates for fluorescence quenching processes.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the main spontaneous and stimulated transitions in 1.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence quenching dependences 1 − IF/IF0 = f (qEP) (a) and (c) of 1 in TOL (a) and CHCl3 (c) for corresponding quenching wavelengths λq. Solid black lines are linear fittings (a, c). One-photon STED spectra of 1 (b, curves 3, 4, blue and red circles) in TOL (3, blue circles) and CHCl3 (4, red circles). 2PA spectrum (d, curve 2) and two-photon STED spectrum (d, curve 3) of 1 in CHCl3. Normalized absorption spectra (b, curves 1, 2; d, curve 1) and fluorescence spectra (b, curve 1′, 2′; d, curve 1′) of 1 in TOL (b, curves 1, 1′) and CHCl3 (b, curves 2, 2′; d, curve 1′).

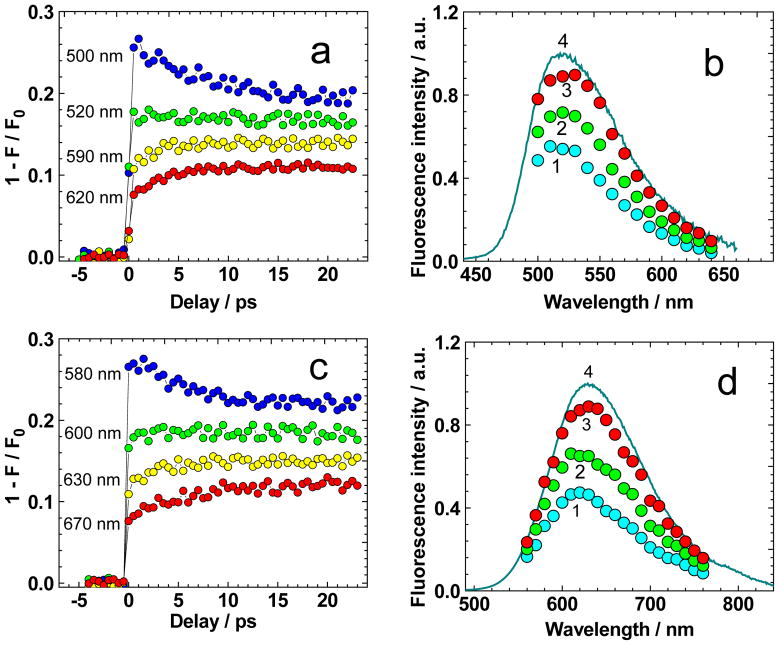

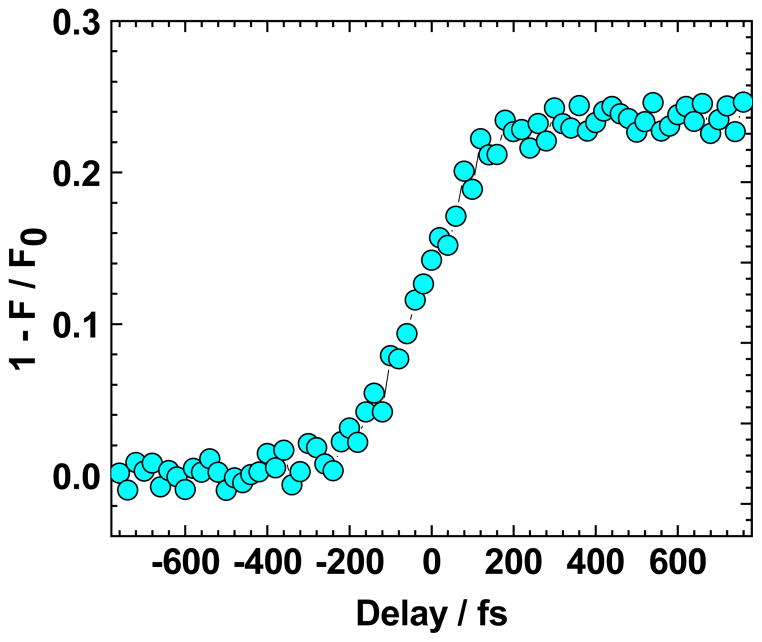

The time-resolved one-photon STED spectra of 1 were determined from the transient quenching efficiency curves, 1 − IF/IF0 = f (τD) (Figure 8a, c), obtained for different λq, and presented in Figure 8b, d. As follows from these data, the degree of fluorescence quenching decreases with time for short quenching wavelength, , and increases for in the picosecond time scale. This finding means a possibility exists to reveal instantaneous stimulated emission contours, σ10 (λ), which reflect picosecond solvate relaxation processes. Time-resolved one-photon STED spectra of 1 exhibit maximal long-wavelength shifts up to ~15–20 nm, with corresponding relaxation time ~5–7 ps, which are typical for the solvate relaxation processes of organic molecules in low-viscosity solvents at room temperature.[36] It should be mentioned that the femtosecond fluorescence quenching method is the most accurate methodology for the determination of the molecular stimulated-emission cross-sections, which are important parameters for STED microscopy applications. At the same time, high-intensity femtosecond laser pulses cannot realize more than ~50 % depopulation of the excited state S1 due to a short pulse duration τq ≪ τV (τV is the vibrational relaxation time in S0). This finding means that nano- and picosecond laser pulses are more preferable for the development of high-resolution STED microscopy systems.[45]

Figure 8.

Transient quenching dependences 1 − IF/IF0 = f (τD) (a, c) of 1 in TOL (a) and CHCl3 (c) for corresponding quenching wavelengths λq. Time-resolved one-photon STED spectra of 1 (b, d) for τD = 0 ps (1, cyan circles), 2 ps (2, green circles), and 6 ps (3, red circles) in TOL (b) and CHCl3 (d). Normalized fluorescence spectra (b, d, curves 4) of 1 in TOL (b) and CHCl3 (d).

One- and two-photon bioimaging

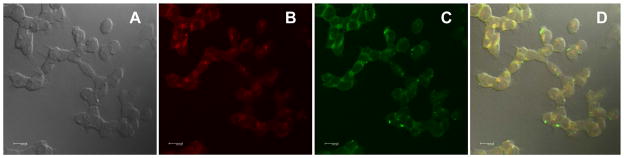

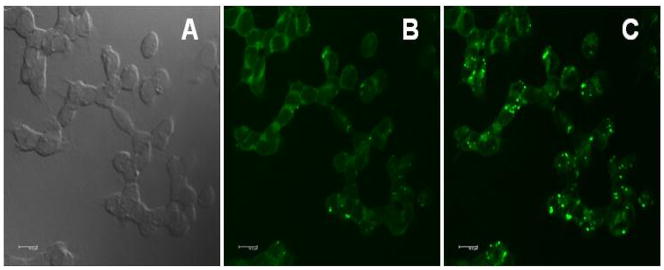

We previously demonstrated that encapsulation of hydrophobic 2PA probes in Pluronic® F-127 is a feasible method for delivering fluorescent probes into the lysosomes of HCT 116 cells.[46, 47] Pluronic® F-127 is a nonionic, surfactant polyol (molecular weight approximately 12,500 daltons) that has been found to facilitate the solubilization of water-insoluble dyes and other materials in physiological media.[48] Probe 1 was encapsulated in Pluronic® F-127, and upon formation of micelles was incubated with HCT 116 cells. In order to demonstrate the potential utility of probe 1 for 2PFM cellular imaging, its cell viability was evaluated. Viability assays in an epithelial colorectal carcinoma cell line, HCT 116, were conducted via the MTS assay (Figure S1 shows the viability data for HCT 116 cells after treatment with several concentrations of dye-encapsulated micelles for 24 h). The data indicate that probe 1 has low cytotoxicity (~ 95% viability) over a concentration range from 1 to 30 μM, appropriate for cell imaging. To determine the location of the probe 1 in the cell, a colocalization study of probe 1 with well-known lysosomal selective dye (Lysotracker Red) in HCT 116 cells was conducted. One-photon fluorescence images, collected for Lysotracker Red and probe 1, are shown in Figure 9b and c, respectively, as well as the differential interference contrast (DIC) image (Figure 9a), along with the overlap image of a, b, and c (Figure 9d). One can observe in Figure 9d, the colocalization of both probes suggesting a similar uptake mechanism for both the Lysotracker dye and probe 1. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated within Slidebook 5.0, imaging processing software. The correlation coefficient of probe 1 relative to LysoTrackerRed is higher than 0.8, supporting lysosomal colocalization. 2PFM imaging (Figure 10c) revealed remarkable contrast when compared to the one-photon fluorescence (Figure 10b), suggesting the potential that this probe-micelle formulation has in bioimaging.

Figure 9.

Confocal fluorescence images of HCT 116 cells incubated with 2PA probe 1 encapsulated in Pluronic® F-127 (20 μM, 1 h) and Lysotracker Red (75 nM, 1 h). DIC (a), one-photon fluorescence image showing Lysotracker Red (b) and 2PA probe 1 encapsulated in Pluronic® F-127 micelles (c). (d) Colocalization (overlay of B and C). 10 μm scale bar.

Figure 10.

One-and two-photon fluorescence micrographs of HCT 116 cells incubated with probe 1 encapsulated in Pluronic® F-127 (20 μM, 1 h). DIC (a), one-photon fluorescence (b), and two-photon fluorescence images (c), 80 MHz, 75 fs pulse width tuned to 700 nm, 63x objective. 10 μm scale bar.

Conclusion

The synthesis, linear photophysical, and nonlinear optical properties of new push-pull fluorene derivative 1, with a strong electron-donor di-p-tolylamine group and electron-acceptor acetylthiophene, were investigated in a number of organic solvents at room temperature as a potential fluorescent label for 2PFM applications. The steady-state absorption spectra of 1 exhibited weak dependence on solvent properties, while fluorescence emission revealed strong solvatochromic behavior with a maximum Stokes shift of more than 180 nm in CHCl3. The values of fluorescence quantum yields of 1 in different media are high (~0.6–1.0) and independent of excitation wavelength in a whole spectral range of absorption. Fluorescence lifetimes corresponded to a single exponential decay and were in good agreement with theoretical predictions, based on the Strickler-Berg approach. The excitation anisotropy spectra of 1 revealed only one electronic transition S0 → S1 in the main long-wavelength absorption band, relatively fast rotational correlation time in low-viscosity solvents, θ ≈ 190 ps, and small effective rotational molecular volume V ≈ 160 Å3, which could be associated with slipping boundary conditions in solute-solvent dynamics. The degenerate 2PA spectra of 1 were obtained by two independent methods and exhibited two well-defined 2PA bands. The strongest one was observed in the spectral range λex ≈ 880–900 nm with maximal cross-sections δ2PA ≈ 400–600 GM and corresponded to the linear long-wavelength absorption contour. That is suitable for practical applications of 1 in 2PFM with commercially available femtosecond Ti:sapphire laser systems.

The electronic structure of 1 was analyzed based on the results of TDDFT quantum-chemical calculations, and the nature of the main electronic transitions responsible for linear and nonlinear optical properties was determined. The steady-state one- and two-photon stimulated emission spectra of 1 were obtained over a broad spectral region and a maximum two-photon cross section δ2PE ≈ 400 GM was shown. This value is close to the corresponding ground-state 2PA cross-sections in the main linear absorption band of 1, which presumably reflects the two-photon nature of these processes. The time-resolved one-photon STED spectra were obtained for the first time using a femtosecond fluorescence quenching method. The spectral shifts of the stimulated emission contours, σ10 (λ), up to 20 nm, were observed within a time period of 5–7 ps due to the solvate relaxation processes. It seems that the presented fluorescence quenching methodology is a promising and relatively simple way of estimating the time-resolved fluorescence spectra of organic molecules. The potential application of 1 in bioimaging was demonstrated via one- and two-photon fluorescence microscopy of epithelial colorectal carcinoma HCT 116 cells encapsulated in Pluronic® F-127 micelles. Based on these results, a new fluorene derivative 1, exhibiting relatively large 2PA and two-photon stimulated emission cross-sections, high-fluorescence quantum yield, and photochemical stability, has good potential for 2PFM applications as a fluorescent label, including STED bioimaging microscopy.

Experimental Section

Materials and synthetic methods

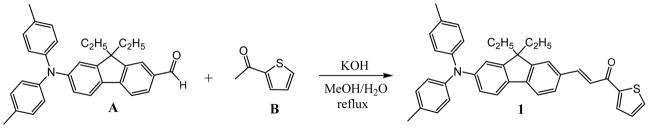

We report the preparation of a new push-pull fluorene derivative bearing a strong electron-donor di-p-tolylamine group and acetylthiophene as an electron acceptor. The preparation of the push-pull compound 1 was carried out using commercially available 1-(thiophen-2-yl)ethanone (B) and aldehyde derivative A, as shown in Scheme 1. Claisen-Schmidt condensation was performed in MeOH and KOH under reflux-affording compound 1 in 45% yield. The analysis of the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra confirmed the expected molecule. Synthesis of 7-(di-p-tolylamino)-9,9-diethyl-9H-fluorene-2-carbaldehyde (A) will be described elsewhere. 1-(Thiophen-2-yl)ethanone (B) was commercially available. The 1H and 13C NMR measurements were performed using a Varian 500 NMR spectrometer at 500 MHz with tetramethysilane (TMS) as the internal reference. For 1H (referenced to TMS at δ = 0.0 ppm) and for 13C (referenced to CDCl3 at δ = 77.0 ppm), the chemical shifts of 1H and 13C spectra were interpreted with the support of CS ChemDraw Ultra, version 11.0. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) analysis was performed in the Department of Chemistry, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of chromophore 1.

Synthesis of (E)-1-(2-(di-p-tolylamino)-9,9-diethyl-9H-fluoren-7-yl)-3-(thiophen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (1)

1-(Thiophen-2-yl)ethanone (0.14 g, 1.12 mmol) was added to the solution of KOH (0.075 g, 1.34 mmol) in MeOH/H2O 5:1 (20 mL). After dissolution 7-(di-p-tolylamino)-9,9-diethyl-9H-fluorene-2 carbaldehyde (0.50 g, 1.12 mmol) was added to the mixture and stirred for 48 h at reflux. A solid-product precipitate was filtered, washed with hexane, and dried. Recrystallization in hexanes provided yellow solid 0.27 g (45% yield), m.p. 172–173 °C, 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.95 (s, 1H), 7.92 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (d, J = 5Hz, 1H), 7.61 (s, 2H), 7.54 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H)7.45 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (t, J =5 Hz, 1H), 7.06-7.01 (m, 8H), 6.98 (dd, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 2.32 (s, 6H), 2.01-1.88 (m, 4H), .382-0352 (t, J = 15 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 182.1, 152.0, 150.4, 148.6, 145.8, 145.4, 145.0, 144.6, 134.4, 133.5, 132.5, 132.4, 131.5, 129.8, 128.3, 128.1, 124.4, 122.6, 122.0, 120.8, 119.9, 119.2, 117.4, 56.0, 32.6, 20.8, 8.5 ppm. HRMS-ESI theoretical m/z [M+H]+ = 554.24, found 554.25, theoretical m/z [M+Na]+ = 576.24, found 576.23.

Linear photophysical and photochemical characterization

The linear steady-state absorption, excitation, fluorescence, and excitation anisotropy spectra of 1 were investigated in spectroscopic grade HEX, TOL, CHCl3, THF and ACN at room temperature. The steady-state absorption measurements were carried out using an Agilent 8453 UV-visible spectrophotometer and 10-mm path length quartz cuvettes with dye concentrations C ~ (2–4) · 10−5 M. The steady-state excitation, fluorescence, and excitation anisotropy spectra were obtained with a PTI QuantaMaster spectrofluorimeter in a photon-counting regime using 10-mm spectrofluorometric quartz cuvettes with C ≤ 10−6 M. All excitation and fluorescence spectra were corrected for the spectral responsivity of the PTI excitation and detection system, respectively. Excitation anisotropy measurements were performed in the “L-format” configuration,[36] and a weak emission of pure solvent and scattered light were extracted. The fundamental anisotropy value of 1 r0, was determined in viscous pTHF, in which the rotational correlation time, θ = ηV/(kT) ≫ τ (τ, V, k, and T are the viscosity of solvent, effective rotational molecular volume, Boltzmann’s constant, and absolute temperature, respectively) and experimentally observed anisotropy:[36]

| (2) |

The values of fluorescence quantum yields, Φ, of 1 were determined in low concentrated solutions (C ~ 10−6 M) by a standard relative method with 9,10-diphenylanthracene in cyclohexane as a reference (Φ ≈ 0.95).[36] Fluorescence lifetimes of 1, τ, were obtained using a time-correlated single-photon counting PicoHarp 300 system with time resolution ≈ 80 ps. Linear polarized femtosecond excitation, oriented by the magic angle, was used in the lifetime measurements to avoid the effect of rotational molecular movement on τ. The quantum yields of the photochemical decomposition of 1, Φph, were determined under cw one-photon excitation with a LOCTITE 97034 UV lamp (excitation wavelength, λex ≈ 405 nm, average irradiance ≈ 90 mW/cm2) by the absorption method described previously.[49]

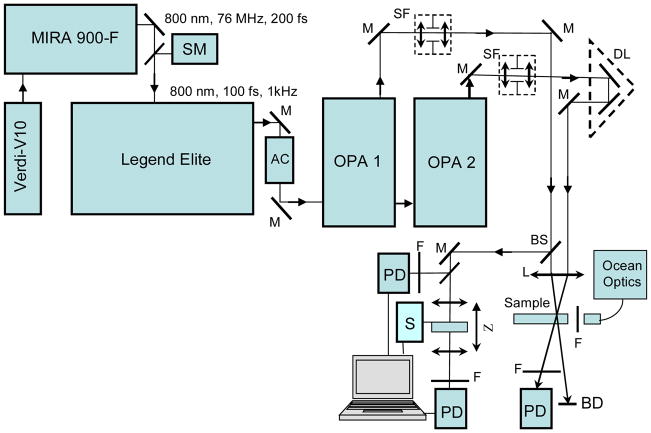

2PA and STED measurements

The investigations of the 2PA and STED properties of 1 were performed with a femtosecond laser system (Coherent, Inc.), schematically depicted in Figure 11. The output of a Ti:Sapphire laser (Mira 900-F, tuned to 800 nm, with a repetition rate, f = 76 MHz, average power ≈ 1.1 W and pulse duration, τ ≈ 200 fs), pumped by the second harmonic of cw Nd3+:YAG laser (Verdi-10), was regeneratively amplified with a 1-kHz repetition rate (Legent Elite USP) providing ≈ 100 fs pulses (FWHM) with energy ≈ 3.6 mJ/pulse. This output at 800 nm was split in two separate beams with average power ≈ 1.8 W each and pumped two ultrafast optical parametric amplifiers (OPerA Solo (OPA), Coherent Inc.) with a tuning range 0.24-20 μm, τP ≈ 100 fs (FWHM), and pulse energies, EP, up to ≈ 100 μJ. A single laser beam from the first OPA was used for direct 2PA cross-section measurements by the open-aperture Z-scan method.[33] The same laser exit was coupled with a PTI QuantaMaster spectrofluorimeter (this part is not shown in Figure 11), and the relative 2PF method[34] was used for 2PA measurements, as well as Rhodamine B in methanol and fluorescein in water (pH=11) as standards.[50] The quadratic dependence of 2PF intensity on the excitation power was confirmed for each excitation wavelength, λex. The investigation of the steady-state and time-resolved STED spectra of 1 were performed based on the pump-probe fluorescence quenching technique,[24] using two laser beams from the separate OPA systems simultaneously pumped at 800 nm (Figure 11). The fluorescence quenching method is based on one- or two-photon stimulated emission transitions S1 → S0 (S0 and S1 are the ground and first excited electronic states of 1, respectively), which can depopulate electronic state S1 (after a short time delay, τD ≪ τ, following the excitation) and decrease the fluorescence intensity observed perpendicular to the excitation beam. The first (pump) beam from OPA was set at 400 nm (τP ≈ 100 fs; f = 1 kHz; EP ≈ 1 μJ) and was used for one-photon fluorescence excitation of 1. The second (quenching) beam from another OPA was delayed by a M-531.DD optical line with a retroreflector and was tuned in a broad spectral range (quenching wavelengths 440 nm ≤ λq ≤ 1600 nm; quenching pulse duration, τq ≈ 100 fs; f = 1 kHz; quenching pulse energies, 0.5 μJ ≤ qEP ≤ 8 μJ). The integral fluorescence intensities from the investigated solutions of 1 were observed perpendicularly to the excitation beam and were measured with an H4000 fiber optic spectrometer (Ocean Optics Inc.). In the case of one-photon STED transitions (λq belongs to the fluorescence region of 1), the pumping and quenching laser beams, with vertically oriented linear polarizations, were focused on the waists of the radiuses p r0 ≈ 0.5 mm and qr0 ≈ 0.2 mm (HW1/eM), respectively, and were recombined at a small angle (< 5°) in a 1-mm path length flow quartz cuvette with a sample solution. Two-photon STED transitions (λq/2 belongs to the fluorescence region of 1) were realized in a similar excitation and quenching geometry with p r0 ≈ 0.18 mm and q r0 ≈ 0.1 mm (HW1/eM), respectively. The optimum optical density of the investigated solutions at λex was in the range 0.3 – 0.4. The efficiency of the fluorescence quenching processes is characterized by the degree of fluorescence quenching, 1 − IF/IF0, where IF and IF0 are the integral fluorescence intensity observed from one excitation pulse in the presence and absence of the quenching beam, respectively. In the case of one-photon quenching, this value can be expressed as:[14]

Figure 11.

Simplified schematic diagram of the experimental setup: SM - spectrometer; AC - optical autocorrelator; M - 100% reflection mirrors; BS - beam splitter; SF - space filters; DL - optical delay line with retro-reflector; PD -calibrated Si and/or InGaAs photodetectors; L - focusing lenses; F - set of neutral and/or interferometric filters; S -step motor; Sample – 1-mm flow quartz cuvette with investigated solutions; Z - Z-scan setup; BD - beam dump. Additional details are presented in the text.

| (3) |

where σ10 (λq), h, c are the one-photon stimulated emission cross-section at λq, Planck’s constant, and velocity of light in a vacuum, respectively. In the case of the two-photon fluorescence-quenching process, equation (3) can be written as:[14]

| (4) |

where δ2PE (λq) is the two-photon stimulated emission cross-section at λq. Equations (3) and (4) were obtained under several reasonable approximations that corresponded to the employed experimental conditions (Gaussian spatial and temporal shapes of the pumping and quenching beams; constant field approximation; spectral independence of the fluorescence quantum yield of 1; sufficiently high photochemical stability of the investigated solutions, etc.) and described previously in detail.[14] The slopes of the linear experimental dependences 1 − IF/IF0 ~ σ10 (λq) · qEP and were used for the determination of the σ10 (λq) and δ2PE (λq) cross-sections. It should be mentioned that the linearity of these dependences can serve as a proof of the one- or two-photon nature of the observed STED processes and was confirmed for each excitation wavelength. Also, it is important to emphasize that one-photon excited state absorption (ESA) processes cannot affect the efficiency of fluorescence quenching in cases in which the value of the fluorescence quantum yield is independent of the excitation wavelength. This means that direct radiationless transitions from highly excited electronic states to S0 are negligible, and additional ESA processes cannot decrease fluorescence intensity. The steady-state one- and two-photon STED spectra of 1 were obtained for the constant value of τD = 20 ps, which is an optimal time delay for the investigation of organic molecules with nanosecond fluorescence lifetimes.[14, 24] It was reasonable to assume that a negligible amount of fluorescence photons were emitted in the time period of 20 ps after excitation, and all excited state vibrational and solvate relaxation processes in 1 were finished.[36] The time-resolved STED spectra of 1 were obtained for one-photon stimulated emission transition by tuning of λq in the fluorescence spectral range and for a varied time delay between the pump and quench pulses in the range 0 – 20 ps. The time-resolution of the used experimental setup was approximately 300 fs. Typical dependence 1 − IF/IF0 = f (τD), determining the time resolution of this system, is shown in Figure 12, with the step in τD ≈ 6.7 fs. It should be mentioned that no photochemical or other accumulative effects were observed in the flow sample solutions under the experimental conditions.

Figure 12.

Typical dependence 1 − IF/IF0 = f (τD) for 1 in TOL (λq ≈ 520 nm).

Computational details

Quantum-chemical calculations of the electronic structure of 1 were performed with the Gaussian 09 program package.[35] The ground state geometry was optimized by the DFT/6–31(d,p)/B3LYP method. The time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT/6–31(d,p)/B3LYP) was employed to obtain molecular orbitals, excitation energies, oscillator strengths, and steady-state and transition dipoles for the optimized structure. The values of 2PA cross-sections were estimated by the well-known expression of Ohta et al.,[41] based on the SOS approach and the simplified three-level model of 2PA processes.[42]

Preparation methodologies of dye-encapsulated micelles, cell incubation and fluorescence bioimaging

Encapsulation of probe 1 in Pluronic® F-127

A solution containing 12.5 mg of Pluronic® F-127 in 5mL of PBS buffer (pH= 7.4) was mixed with a solution containing dye 1 (2.5 mg) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 h to slowly evaporate the CH2Cl2. The mixture was filtered through a Whatman 2 μm pore size disposable filter to generate stock solution. The concentration of stock solution was 252 μM, estimated by absorption spectra.

Cell culture and incubation

HCT 116 cell (purchased from America Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in RPMI-1640, supplemented with 10% FBS, and 1% peniclin, 1% streptomycin, at 37 °C, in a 95% humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. N° 1 round 12 mm coverslips were treated with poly-D-lysine, to improve cell adhesion, and washed (3×) with PBS buffer solution. The treated cover slips were placed in 24-well plates and 40,000 cells/well were seeded and incubated for 36 h before incubation with the dye. From a 252 μM stock solution of Pluronic® F-127 encapsulated dye 1 a 20 μM solution in culture media was freshly prepared and also a 75 nM solution of Lysotracker Red (Invitrogen). These solutions were used to incubate the cells for 1 h. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS three times, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 10 min, and incubated twice with NaBH4 (1mg/mL) in PBS at room temperature for 10 min. The cells were then washed with PBS twice and mounted on microscopy slides with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) mounting media for imaging.

One-photon and two-photon fluorescence imaging

One- and two-photon images were recorded on a Leica TCS SP5 II laser-scanning confocal microscope system. For one-photon imaging, cells were excited at 405 nm. Fluorescence was collected in a range from 450 nm to 550 nm. The confocal pinhole was applied for better image quality. Two-photon fluorescence imaging was recorded on Leica TCS SP5 microscope system coupled to a tunable Coherent Chameleon Vision S laser (80 MHz, modelocked, 75 fs pulse width, tuned to 700 nm). Two-photon induced fluorescence was collected with a water immersion 63x objective (HCX Pl APO CS 63.0×1.20 WATER UV).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the Institute of Bioimaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health (1 R15 EB008858-01), the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (grant 1.4.1.B/153), the National Science Foundation (ECCS-0925712, CHE-0840431, and CHE-0832622), and the National Academy of Sciences (PGA-P210877) for their support of this work.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/ or from the author.

Contributor Information

Prof. Kevin D. Belfield, Email: belfield@mail.ucf.edu.

Mykhailo V. Bondar, Email: mbondar@mail.ucf.edu.

References

- 1.Kawata S, Kawata Y. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1777–1788. doi: 10.1021/cr980073p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yanez CO, Andrade CD, Yao S, Luchita G, Bondar MV, Belfield KD. Appl Mater Interf. 2009;1:2219–2229. doi: 10.1021/am900587u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendonca CR, Correa DS, Marlow F, Voss T, Tayalia P, Mazur E. Appl Phys Lett. 2009;95:113309/113301–113303. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corredor CC, Huang ZL, Belfield KD, Morales AR, Bondar MV. Chem Mater. 2007;19:5165–5173. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding JB, Takasaki KT, Sabatini BL. Neuron. 2009;63:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moneron G, Hell SW. Opti Express. 2009;17:14567–14573. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.014567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin TC, Chen YF, Hu CL, Hsu CS. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:7075–7080. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlot M, Izard N, Mongin O, Riehl D, Blanchard-Desce M. Chem Phys Lett. 2006;417:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reisner DE, Field RW, Kinsey JL, Dai HL. J Chem Phys. 1984;80:5968–5978. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lattante S, Barbarella G, Favaretto L, Gigli G, Cingolani R, Anni M. Appl Phys Lett. 2006;89 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi T, Savatier JB, Jordan G, Blau WJ, Suzuki Y, Kaino T. Appl Phys Lett. 2004;85:185–187. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulygin AD, Bykova EE, Zemlyanov AA, Zemlyanov AA. Russian Physics Journal. 2009;52:862–870. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebane A, Drobizhev M, Makarov NS, Beuerman E, Zhao Y, Spangler CW. Proc SPIE. 2010;7599:75990W/75991–75912. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belfield KD, Bondar MV, Yanez CO, Hernandez FE, Przhonska OV. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:7101–7106. doi: 10.1021/jp902060m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hales JM, Matichak J, Barlow S, Ohira S, Yesudas K, Brédas JL, Perry JW, Marder SR. Science. 2010;327:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1185117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He GS, Tan LS, Zheng Q, Prasad PN. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1245–1330. doi: 10.1021/cr050054x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rumi M, Perry JW. Adv Opt Photon. 2010;2:451–518. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wildanger D, Rittweger E, Kastrup L, Hell SW. Opt Express. 2008;16:9614–9621. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.009614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W, Niu H. Phys Rev. 2011;A 83:023830/023831–023835. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusba J, Lakowicz JR. J Chem Phys. 1999;111:89–99. doi: 10.1063/1.479256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I, Kusba J, Bogdanov V. Photochem Photobiol. 1994;60:546–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gryczynski IK, Gryczynski J, Malak Z, Lakowicz H, JR J Fluoresc. 1998;8:253–261. doi: 10.1023/A:1022561801704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gryczynski IBV, Lakowicz JR. J Fluoresc. 1993;3:85–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00865322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belfield KD, Bondar MV, Morales AR, Padilha LA, Przhonska OV, Wang X. ChemPhysChem. 2011;12:2755–2762. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blom H, Rönnlund D, Scott L, Spicarova Z, Widengren J, Bondar A, Aperia A, Brismar H. BMC Neuroscience. 2011;12:16, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagerl UV, Bonhoeffer T. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9341–9346. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0990-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hao F, Zhang X, Tian Y, Zhou H, Li L, Wu J, Zhang S, Yang J, Jin B, Tao X, Zhou G, Jiang M. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:9163–9169. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbotto A, Beverina L, Bozio R, Bradamante S, Ferrante C, Pagani GA, Signorini R. Adv Mater. 2000;12:1963–1967. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belfield KD, Bondar MV, Hernandez FE, Przhonska OV, Wang X, Yao S. PhysChemChemPhys. 2011;13:4303–4310. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01511c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belfield KD, Andrade CD, Yanez CO, Bondar MV, Hernandez FE, Przhonska OV. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:14087–14095. doi: 10.1021/jp107343k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Nguyen DM, Yanez CO, Rodriguez L, Ahn HY, Bondar MV, Belfield KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12237–12239. doi: 10.1021/ja1057423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawlicki M, Collins HA, Denning RG, Anderson HL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3244–3266. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheik-Bahae M, Said AA, Wei TH, Hagan DJ, Van Stryland EW. IEEE J Quantum Electron. 1990;26:760–769. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu C, Webb WW. J Opt Soc Am B. 1996;13:481–491. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery J, JA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam NJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09, Revision A.2. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. Kluwer; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strickler SJ, Berg RA. J Chem Phys. 1962;3:814–822. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu C, Zwanzig R. J Chem Phys. 1974;60:4354–4357. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morales AR, Schafer-Hales KJ, Yanez CO, Bondar MV, Przhonska OV, Marcus AI, Belfield KD. ChemPhysChem. 2009;10:2073–2081. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belfield KD, Bondar MV, Frazer A, Morales AR, Kachkovsky OD, Mikhailov IA, Masunov AE, Przhonska OV. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:9313–9321. doi: 10.1021/jp104450m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohta K, Antonov L, Yamada S, Kamada K. J Chem Phys. 2007;127:084501–084512. doi: 10.1063/1.2753490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orr BJ, Ward JF. Molecular Physics. 1971;20:513–526. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Nguyen DM, Yanez CO, Rodriguez L, Ahn HY, Bondar MV, Belfield KD. Biomed Opt Express. 2010;1:453–462. doi: 10.1364/BOE.1.000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deshpande AV, Beidoun A, Penzkofer A, Wagenblast G. Chem Phys. 1990;142:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leutenegger M, Eggeling C, Hell SW. Opt Express. 2010;18:26417–26429. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.026417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao S, Ahn HY, Wang XH, Fu J, Van Stryland EW, Hagan DJ, Belfield KD. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3965–3974. doi: 10.1021/jo100554j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andrade CD, Yanez CO, Qaddoura MA, Wang X, Arnett CL, Coombs SA, Bassiouni R, Bondar MV, Belfield KD. J Fluoresc. 2011;21:1223–1230. doi: 10.1007/s10895-010-0801-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lemaster JJ, Trollinger DR, QT, Cascio WE, Ohata H. Methods Enzymol. 1999;302:341–356. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)02031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corredor CC, Belfield KD, Bondar MV, Przhonska OV, Hernandez FE, Kachkovsky OD. J Photochem Photobiol C. 2006;184:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makarov NS, Drobizhev M, Rebane A. Opt Express. 2008;16:4029–4047. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.004029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.