Abstract

Cells invest a significant amount of their energy synthesizing proteins, and a large portion of the energy expenditure goes into making ribosomes, the RNA-protein machines at the centre of translation. When ribosomes are damaged in a cell, i.e., during stressful conditions, cells must first recognize the damage and then mount a response. Remme and colleagues show that instead of having to rebuild ribosomes from scratch, bacteria can repair ribosomes by replacing damaged proteins in situ, thereby saving significant time and energy. Given the central role of translation, such repair mechanisms might be widespread in nature.

Being in an automobile accident is a painful experience, not least due to having to face the insurance claims afterwards. Depending on the severity of the wreck, the insurance company decides whether the car is “totalled” or can be repaired. Cells face analogous budgetary concerns when handling their capacity to make proteins. Given its central role in a cell, translation is heavily monitored and regulated, and the translational capacity of a cell can change in minutes or even more quickly (Jones et al., 1987, Ashe et al., 2000). Protein synthesis in all cells occurs on the ribosome, a large macromolecular machine that, in bacteria, is about 2.5 MDa, and almost twice as big in eukaryotes. A bacterium such as Escherichia coli can spend large portions of its energy budget simply assembling ribosomes de novo (Keener & Nomura, 1996).

The ribosome is composed of 3–4 large RNAs that are central to its function. However, it’s also clear that ribosomal proteins make significant contributions to all of the steps of translation, from the entry of mRNA into the ribosome (Takyar et al., 2005) and mRNA decoding (Schmeing et al., 2009) to peptidyl transfer (Voorhees et al., 2009) and the exit of the synthesized protein from the ribosomal exit tunnel (Seidelt et al., 2009). Given that partially functional ribosomes can be lethal to cells (Thompson et al., 2001, Ali et al., 2006), it would make sense that cells closely monitor ribosomes to ensure that they are functioning correctly. Remme and colleagues tackled the question of how cells handle ribosome damage by looking at the E. coli ribosome, both in vitro and in vivo. Their results suggest that ribosome repair is likely an important strategy for cell survival.

In their first experiments, Remme and co-workers exploited a well-established method to inactivate ribosomes by chemical modification of cysteine residues in ribosomal proteins. The authors then incubated the chemically damaged ribosomes with undamaged ribosomal proteins in conditions compatible with ribosome assembly. Some proteins were exchanged in the process, and the ribosomes were restored to nearly wild-type levels of activity. Extending the experiments to see what happens inside living cells, Remme and colleagues then stressed E. coli cells by letting them grow into stationary phase, when chemical damage accumulates (Nystrom, 2004), and when de novo ribosome assembly is negligible (Molin et al., 1977). Under these in vivo conditions, a significant number of ribosomal proteins were found to be replaced.

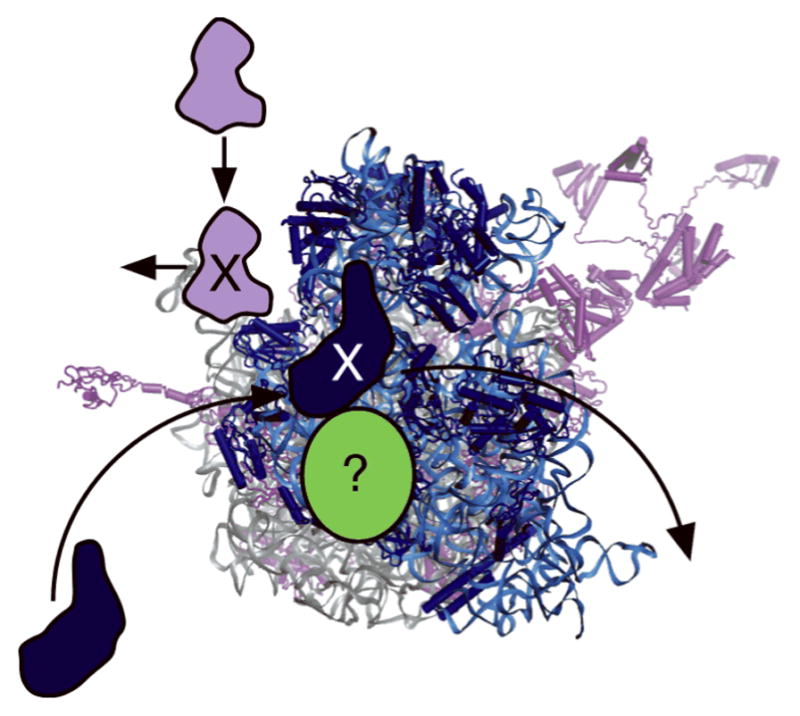

In all, Remme and colleagues documented the exchange of many more ribosomal proteins in vivo than in vitro, suggesting that both passive and active mechanisms likely play a role in ribosome repair (Figure 1). It will be important in future experiments to identify the factors responsible for active exchange of ribosomal proteins in vivo, and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. For example, are proteases and chaperones involved in repair, and are there energy-consuming steps? Another outstanding question is whether such repair mechanisms are conserved in other organisms.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of ribosome repair in Escherichia coli. Some ribosomal proteins can exchange spontaneously, whereas others might require active mechanisms, as indicated by the question mark.

Some clues to the generality of the phenomenon of ribosome repair can be gleaned from observations on other macromolecular assemblies. Another complicated machine that is repaired in situ is photosystem II, which has a half-life of only a few minutes due to photo damage. Instead of replacing the entire complex, the damaged protein D1 in photosystem II is removed from the complex and a new copy is co-translationally inserted (Mulo et al., 2008). The mechanism of repair has not been worked out in detail, but seems to involve both proteases that help to clear the damaged D1 protein, and chaperones that stabilize the partially disassembled photosystem while it is being repaired. An analogous process might be required for ribosomes.

The results of Remme and colleagues suggest that ribosomes are more dynamic and possibly more heterogeneous than is generally appreciated. Other recent data consistent with ribosome heterogeneity and ribosome repair span the phylogenetic spectrum from E. coli to yeast to mammals. E. coli cells treated with the antibiotic kasugamycin begin to lose proteins from the ribosomes, and selectively translate leaderless mRNAs (Kaberdina et al., 2009). Notably, the formation of protein-deficient ribosomes seems to result from changes in pre-existing ribosomes, as opposed to synthesis of new ribosomes (Kaberdina et al., 2009). In yeast, many of the genes for ribosomal proteins are duplicated. The paralogous genes are functionally non-equivalent, suggesting that yeast ribosomes are functionally heterogeneous (Komili et al., 2007). Finally, evidence is accumulating that ribosome repair might be quite prevalent in the brain. For example, mRNAs for ribosomal proteins are located in dendrites, far from the site of ribosome assembly (Zhong et al., 2006). Future work is certain to unravel more interesting examples of how cells budget their energy to make the best use of ribosomes that they have already assembled.

References

- Ali IK, Lancaster L, Feinberg J, Joseph S, Noller HF. Deletion of a conserved, central ribosomal intersubunit RNA bridge. Mol Cell. 2006;23:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe MP, De Long SK, Sachs AB. Glucose depletion rapidly inhibits translation initiation in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:833–848. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PG, VanBogelen RA, Neidhardt FC. Induction of proteins in response to low temperature in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2092–2095. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2092-2095.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaberdina AC, Szaflarski W, Nierhaus KH, Moll I. An unexpected type of ribosomes induced by kasugamycin: a look into ancestral times of protein synthesis? Mol Cell. 2009;33:227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keener J, Nomura M. Regulation of Ribosome Synthesis. In: Neidhardt FC, Curtiss R III, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Chapter 90 Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Komili S, Farny NG, Roth FP, Silver PA. Functional specificity among ribosomal proteins regulates gene expression. Cell. 2007;131:557–571. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molin S, Von Meyenburg K, Maaloe O, Hansen MT, Pato ML. Control of ribosome synthesis in Escherichia coli: analysis of an energy source shift-down. J Bacteriol. 1977;131:7–17. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.1.7-17.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulo P, Sirpio S, Suorsa M, Aro EM. Auxiliary proteins involved in the assembly and sustenance of photosystem II. Photosynth Res. 2008;98:489–501. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystrom T. Stationary-phase physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:161–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeing TM, Voorhees RM, Kelley AC, Gao YG, Murphy FVt, Weir JR, Ramakrishnan V. The crystal structure of the ribosome bound to EF-Tu and aminoacyl-tRNA. Science. 2009;326:688–694. doi: 10.1126/science.1179700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidelt B, Innis CA, Wilson DN, Gartmann M, Armache JP, Villa E, Trabuco LG, Becker T, Mielke T, Schulten K, Steitz TA, Beckmann R. Structural Insight into Nascent Polypeptide Chain-Mediated Translational Stalling. Science. 2009 Oct 29;2009 doi: 10.1126/science.1177662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takyar S, Hickerson RP, Noller HF. mRNA helicase activity of the ribosome. Cell. 2005;120:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Kim DF, O’Connor M, Lieberman KR, Bayfield MA, Gregory ST, Green R, Noller HF, Dahlberg AE. Analysis of mutations at residues A2451 and G2447 of 23S rRNA in the peptidyltransferase active site of the 50S ribosomal subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9002–9007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151257098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees RM, Weixlbaumer A, Loakes D, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V. Insights into substrate stabilization from snapshots of the peptidyl transferase center of the intact 70S ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:528–533. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J, Zhang T, Bloch LM. Dendritic mRNAs encode diversified functionalities in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]