Abstract

CD4+ T helper (TH) cells have crucial roles in orchestrating adaptive immune responses. TH2 cells control immunity to extracellular parasites and all forms of allergic inflammatory responses. Although we understand the initiation of the TH2-type response in tissue culture in great detail, much less is known about TH2 cell induction in vivo. Here we discuss the involvement of allergen- and parasite product-mediated activation of epithelial cells, basophils and dendritic cells and the functions of the cytokines interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-25, IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin in the initiation and amplification of TH2-type immune responses in vivo.

CD4+ T cells are crucially involved in adaptive immune responses. Naive CD4+ T cells differentiate into at least four types of T helper (TH) cells1— TH1, TH2, TH17 and inducible regulatory T cells — in response to different infectious agents, commensal microorganisms or self antigens. TH2 cells are indispensable for host immunity to extracellular parasites, such as helminths. They are also responsible for the development of asthma and other allergic inflammatory diseases.

TH2 cells function both through their production of various TH2 cell-associated cytokines, including interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, IL-9, IL-13 and IL-25 (also known as IL-17E), and through their homing to specific tissue compartments. TH2 cells regulate B cell class switching to IgE through their production of IL-4. IgE immune complexes activate innate immune cells (including basophils and mast cells, resulting in their degranulation) by cross-linking high-affinity Fc receptors for IgE (FcεRI) on the surface of these cells. Activated basophils and mast cells secrete various products, including cytokines, chemokines, histamine, heparin, serotonin and proteases, which result in smooth muscle constriction, vascular permeability and inflammatory cell recruitment. The expression of FcεRI by these cells is further enhanced by IgE cross-linking, providing a powerful amplification mechanism of IgE-mediated TH2-type effector responses. TH2 cells also migrate to the lung or intestinal tissues where they recruit eosinophils (through IL-5) and mast cells (through IL-9) leading to tissue eosinophilia and mast cell hyperplasia. By directly acting on epithelial cells (through IL-4, IL-9 and IL-13) and smooth muscle cells (through IL-4 and IL-13), TH2 cells induce mucus production, goblet cell metaplasia and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR). TH2-type cytokines also act on T cells (through IL-4, IL-9 and IL-25), macrophages (through IL-4 and IL-13) and IL-5- and/or IL-13-producing non-B non-T cells (NBNT cells) (through IL-25). TH2 cells may have effects on many other cell types, as IL-4 receptor (IL-4R) and IL-13R are widely expressed throughout the body and, in most instances in which they have been studied, are functional (based on their ability to induce signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) phosphorylation following ligation). TH2 cells also produce amphiregulin1 (an epidermal growth factor family member) and IL-24, which has antitumour effects2. The production of many other cytokines, including IL-2 (REF. 3), IL-10 (REFS 2,4) and IL-21 (REF. 5), is not unique to TH2 cells but these cytokines may participate in mediating and/or regulating the functions of TH2 cells; however, they will not be discussed in detail in this Review.

In addition to being an important TH2-type effector cytokine, IL-4 has a crucial role in the differentiation of TH2 cells in vitro6,7. Through its action on STAT6, IL-4 upregulates the expression of GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3), the master regulator for TH2 cell differentiation8,9, and STAT6 activation is necessary and sufficient for IL-4-mediated GATA3 upregulation10,11. T cell receptor (TCR) signalling can also induce GATA3 expression12. Other signalling pathways, such as that initiated by Notch activation13 and by activation of the WNT signalling pathway through β-catenin and T cell factor 1 (TCF1)14, have been reported to promote GATA3 expression and to lead to the induction of TH2 cell responses in vivo either by allowing IL-4-independent TH2 cell differentiation or by inducing TCR-driven IL-4 production by naive CD4+ T cells. However, whether the Notch and WNT pathways directly control GATA3 transcription or indirectly elevate GATA3 function through their effects on other key factors requires more detailed study.

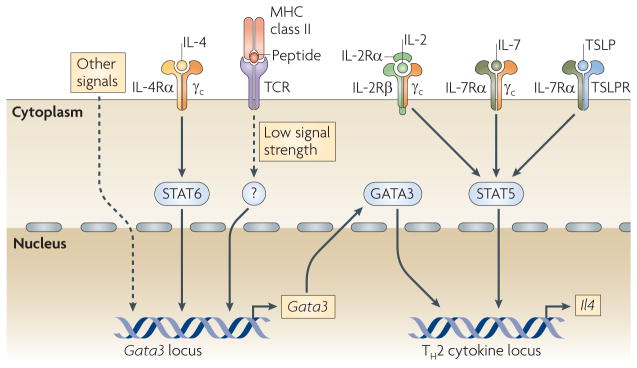

STAT5 activation induced by IL-2 is also crucial for TH2 cell differentiation in vitro 15,16. Neutralization of IL-2 results in the developmental failure of IL-4-producing cells even when IL-4 is exogenously provided and normal cell proliferation is observed15. Introduction of constitutively active STAT5A bypasses the requirement of IL-2 for TH2 cell differentiation. In vivo, activation of STAT5 can be promoted by IL-2, IL-7 and/or thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)3. Strong STAT5 activation may lower the concentration of GATA3 needed for inducing TH2 cell responses. Introduction of constitutively active STAT5A into naive CD4+ T cells in vitro allows TH2 cell differentiation even when the cells are cultured in the absence of IL-4 and in the presence of the TH1 cell-inducing cytokine IL-12 (REF. 16). Although the concentration of GATA3 remains low in such cultures, GATA3 is still essential for TH2 cell differentiation, as constitutively active STAT5A fails to induce TH2 cells differentiation in the absence of Gata3 (REF. 17). Thus, GATA3 expression and STAT5 activation are two crucial elements for TH2 cell differentiation. Indeed, both GATA3 and STAT5 bind to key elements in the TH2 cytokine locus16 (FIG. 1).

Figure 1. TH2 cell differentiation requires both GATA3 expression and STAT5 activation.

GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3) and activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) bind to crucial regulatory elements of the T helper 2 (TH2) cytokine locus and are indispensable for interleukin-4 (IL-4) production and thus TH2 cell differentiation. IL-2, IL-7 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) activate STAT5. Several pathways are involved in regulating GATA3 expression. IL-4, through the activation of STAT6, is important for GATA3 upregulation in vitro. Low signal strength T cell receptor (TCR) activation induces GATA3 expression in an IL-4- and STAT6-independent manner. Other signalling pathways, including the Notch and WNT pathways, have been reported to regulate Gata3 transcription, although whether their effect is direct is currently being investigated. γc, common cytokine receptor γ-chain; R, receptor.

Although the functions of TH2 cells and the requirements of cytokines and transcription factors for their differentiation have been extensively studied in vitro, the factors that initiate and amplify TH2 cell responses in vivo have only recently begun to be clarified. Some TH2-associated cytokines, including TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33, have been shown to be important in certain TH2-associated disease models. Here, we discuss the activation of immune cells including epithelial cells, basophils and dendritic cells (DCs) by allergens and helminth-derived products, and how IL-4, TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33 produced by these cells promotes the development of TH2 cell responses in vivo.

Innate sensing of allergens and helminths

Adaptive immune responses depend on signals from innate immune cells. Discrimination of self versus non-self and danger versus non-danger signals by innate cells and the type of initial activation of these cells determines the nature and magnitude of adaptive immune responses. The first step in the initiation of TH2 cell responses occurs at the tissue sites, including skin, lungs and gut, where allergens or parasites are encountered and the products of allergens and helminths are sensed.

The house dust mite (HDM) allergen is usually contaminated with low levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). It has been shown that low levels of LPS enhance TH2-type responses to inhaled antigens, whereas high levels of LPS result in TH1 cell responses18. Recently, it has been reported that Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression by lung cells (probably lung epithelial cells), but not DCs, is necessary and sufficient for HDM allergen-mediated DC activation and TH2 cell differentiation19. Following activation through TLR4, lung epithelial cells produce TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33 (FIG. 2). How the amount of LPS influences the pattern of cytokine production by lung epithelial cells is not known. Activated lung epithelial cells also produce chemokines, such as CC-chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20), that recruit lung DCs to the airways. Once DCs are activated in the airways under the influence of the LPS-responsive airway epithelial cells, they migrate to the draining lymph nodes where they present antigens to T cells, which subsequently differentiate into TH2 cells. Interestingly, the main HDM allergen, Der p 2, is structurally homologous to MD2 (also known as LY96), a molecule that is required for LPS binding to TLR4 (REF. 20). Therefore, it is possible that Der p 2 induces allergic inflammation in a TLR4-dependent but MD2-independent manner through the activation of airway epithelial cells and the production of TH2-associated cytokines.

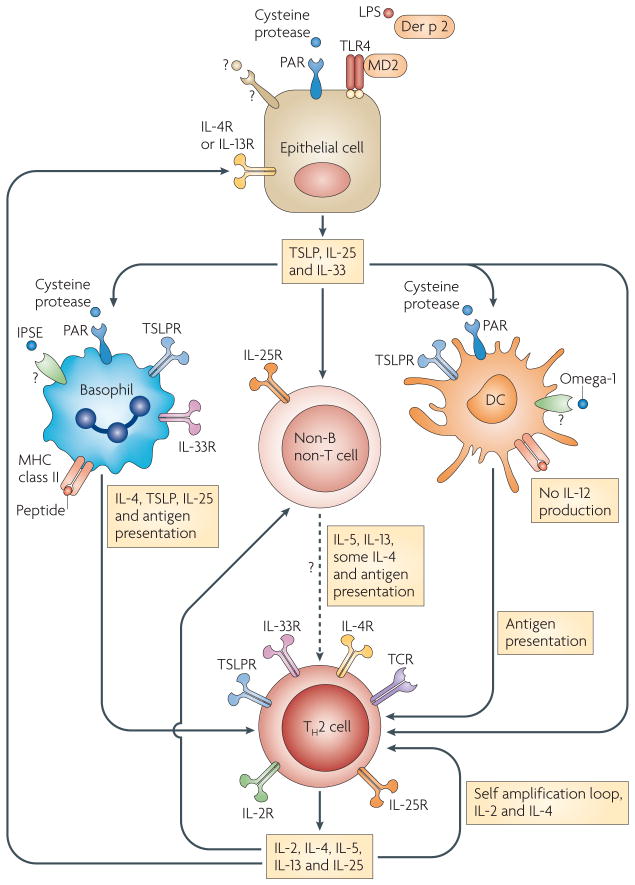

Figure 2. Cytokines have crucial roles in the initiation and amplification of TH2-type immune responses.

Cysteine protease- and/or lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-containing allergens, as well as helminth products, can activate lung and intestinal epithelial cells to produce thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), interleukin-25 (IL-25) and IL-33, which initiate T helper 2 (TH2)-type immune responses by acting on basophils, dendritic cells (DCs) and/or non-B non-T cells. The allergen Der p 2 is structurally homologous to MD2, a component of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signalling complex. A high dose of Der p 2 enhances allergic inflammation in a TLR4-dependent MD2-independent manner. Some cysteine proteases and helminth products, such as IL-4-inducing principle of Schistosoma mansoni eggs (IPSE), can also directly stimulate basophils to produce TSLP and IL-4. Omega-1, a component of S. mansoni egg antigen, modulates DC function to favour a TH2 cell promoting phenotype. Basophils, DCs and possibly other cells can serve as antigen-presenting cells to drive TH2 cell differentiation under the influence of various cytokines such as TSLP, IL-4 and IL-25. Cytokines produced by TH2 cells, including IL-2, IL-4 and IL-25, can self-amplify the differentiation process. At the effector stage, TH2 cells and epithelial cells may further amplify TH2-type responses through a cytokine-mediated positive regulatory loop. Although they are not shown in the figure, other immune cells, including natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, γδ T cells, macrophages, B cells, eosinophils and mast cells, may also participate in the initiation and amplification of TH2-type responses by creating a TH2-biased cytokine environment. In addition, IL-4 may induce IL-12 production by DCs105 or kill TH2-inducing DCs106, suggesting there are also negative regulatory mechanisms for TH2-type immune responses. PAR, protease-activated receptor; R, receptor; TCR, T cell receptor.

Many allergens are cysteine proteases. In vitro treatment of basophils with the cysteine protease papain results in their production of IL-4 and TSLP21 (FIG. 2). Basophils are transiently recruited to the draining lymph nodes in response to allergen challenge and their local production of IL-4 and/or TSLP may explain how TH2 cell responses are stimulated by cysteine protease-containing allergens. The expression of TSLP can also be induced in cells of a human airway epithelial cell line treated with papain or trypsin; IL-4 further promotes such induction22. The effect of trypsin on a human epithelial cell line is mediated by protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2), whereas the induction of TSLP by papain only partially depends on PAR2.

Omega-1 (REFS 23,24), a T2 ribonuclease glycoprotein derived from Schistosoma mansoni egg antigen (SEA), has recently been reported to be a potent TH2 cell-inducing factor (FIG. 2). Omega-1 functions by inhibiting DC activation and lowering the strength of the TCR-dependent signals that naive CD4+ T cells receive, thus enhancing GATA3 production and TH2 cell differentiation (BOX 1). Omega-1 also suppresses IL-12 production by DCs, diminishing TH1 cell induction and, importantly, it induces TH2 cell differentiation in vivo in the absence of IL-4 signalling. How DCs sense omega-1 activity is not known.

Box 1. TCR signal strength regulates T cell differentiation.

T cell receptor (TCR) signal strength regulates T helper 1 (TH1) and TH2 cell differentiation65,101,102. Weak TCR signalling favours TH2 cell differentiation, whereas strong TCR signalling results in TH1 cell differentiation102. When naive CD4+ T cells are stimulated in vitro with low concentrations of cognate peptide12,65,66, they preferentially develop into TH2 cells. Such TH2 cell differentiation can also be achieved by stimulating naive CD4+ T cells with higher concentrations of altered peptide ligands67. The induction of interleukin-4 (IL-4)-producing cells by weak TCR stimulation seems to be also dependent on CD28-mediated co-stimulation66, which is required for the production of IL-2, an essential cytokine for inducing IL-4 production in vitro. Weak TCR stimulation induces IL-4-independent GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3) upregulation and early IL-4 production12. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation in response to TCR signalling strength has a crucial role in regulating TH1 and TH2 cell differentiation12. When naive CD4+ T cells are stimulated with low concentrations of cognate peptide, weak and transient ERK activation is observed. Such weak ERK activation is necessary for inducing sufficient amounts of IL-2 needed for further TH2 cell polarization but is not sufficient to repress TCR-mediated GATA3 induction. When naive CD4+ T cells are stimulated with high concentrations of cognate peptide, ERK activation is high and prolonged. Such strong ERK activation suppresses TCR-mediated GATA3 upregulation and IL-2-mediated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) phosphorylation, two crucial events for inducing IL-4 production, as blockade of the ERK pathway by an ERK kinase inhibitor allows the T cells stimulated with high concentrations of peptide to increase GATA3 transcription and to mediate STAT5 activation in response to IL-2, resulting in IL-4-independent early IL-4 production12.

Although omega-1 seems to be responsible for much of the ability of SEA to induce TH2 cell differentiation in vitro, omega-1-depleted SEA can still induce TH2 cell differentiation in vivo. It has been reported that the IL-4-inducing principle of S. mansoni eggs (IPSE) can mediate FcεRI-dependent IL-4 production by basophils25. Other components of SEA such as lacto-N-fucopentaose III may also be responsible for eliciting TH2 cell responses in vivo26. Specific components from other parasites such as Trichuris muris and Nippostrongylus brasiliensis that are responsible for the induction of TH2-type responses have not been identified. Whether all helminths produce agents that favour TH2 cell differentiation by diminishing TCR signalling strength in a manner similar to omega-1 is not known.

Epithelial cells, basophils and DCs

Lung, skin and intestinal epithelial cells are not only physical barriers to invaders, but also produce cytokines in response to allergens18 and products of helminths27. In humans, epithelial cells, especially keratinocytes from patients with atopic dermatitis, express high levels of TSLP28. Lung epithelial cells respond to HDM and cysteine proteases by producing TSLP18,22. In addition, T. muris infection induces TSLP production by intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), which correlates with nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation in IECs27. Deletion of the NF-κB regulator IκB kinase-β (IKKβ) in IECs reduces their TSLP expression during T. muris infection; T. muris-infected mice in which IKKβ is not expressed in IECs fail to develop TH2-type responses and to expel the helminth, implying a central role for this pathway in T. muris-mediated TH2 cell differentiation.

As mentioned earlier, basophils can produce IL-4 and TSLP in response to cysteine protease allergens or IPSE. Basophils are also effective antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and can promote the differentiation of naive T cells into effector TH2 cells both in vitro and in vivo. It has been reported that when acting as APCs, basophils favour TH2 cell responses, whereas DCs mainly induce TH1 cell responses when the same antigen is presented29. The lower level of MHC class II molecule expression by basophils compared with DCs is consistent with the observation that low-strength TCR signalling results in TH2 cell differentiation.

Administration of antigen–IgE immune complexes induces TH2-type responses both through the FcεRI-mediated activation of basophils and the targeting of antigen to these cells, promoting their role as APCs29. In the papain allergen-induced model of TH2 cell differentiation, basophils seem to be necessary and sufficient as the APCs for TH2 cell induction; DCs are apparently not required30. However, for ovalbumin–alum-induced TH2 cell responses in vivo, DCs have been shown to be crucial31. Similarly, conditional depletion of airway DCs abolishes eosinophilic airway inflammation to inhaled antigen, implying that DCs are essential for the development of asthma32,33. Interestingly, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin with ribonuclease activity serves as an endogenous alarmin to activate myeloid DCs through the TLR2–myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (MYD88) pathway and promotes TH2 cell responses34,35.

The role of basophils during T. muris infection seems to be more complex; depletion of basophils results in failure of helminth expulsion, and mice in which MHC class II expression is restricted to DCs have impaired immunity to T. muris36. However, in mice in which MHC class II expression is restricted to DCs, blocking of interferon-γ (IFNγ) restores TH2 cell-mediated immunity, suggesting that in the absence of IFNγ, basophils are not essential for TH2 cell development. Indeed, depletion of DCs resulted in fewer primed CD4+ T cells than in wild-type mice that had been infected with T. muris, although TH2-type cytokine production was not altered36. By contrast, other APCs, such as macrophages and B cells, are not essential for T. muris-induced TH2 cell responses and worm expulsion36,37. These results suggest that both basophils and DCs are involved in the immune responses to T. muris; however, whether basophils can actually process and present T. muris antigens to CD4+ T cells in vivo remains to be determined.

Basophils are recruited to the draining lymph node two days after exposure to SEA36; however, the overall role of basophils during S. mansoni infection has not been assessed. As omega-1-treated DCs are sufficient to induce TH2 cell responses, basophils may not be as important for the initial TH2 cell-biased immune response in S. mansoni infection as in T. muris infection. It has been recently reported that the recruitment of basophils to the draining lymph nodes after N. brasiliensis infection completely depends on IL-3; however, Il3−/− mice or mice depleted of basophils develop normal TH2 cells38. There are also numerous reports showing that DCs are important APCs during TH2 cell responses to allergens and helminths39–47.

Thus, epithelial cells and basophils have important roles in the initiation of TH2 cell responses by producing TH2-associated cytokines in response to allergen or helminth-derived products. Basophils are also involved in the initiation of some TH2 cell responses by serving as APCs. However, the differential requirements for basophils or DCs as APCs for the induction of TH2 cell responses seem to depend on the nature of the antigens or helminths and/or the particular adjuvant used.

IL-4 and TH2 cell differentiation

Traditionally, IL-4 has been viewed as the keystone of the TH2 cell response. However, although the IL-4–STAT6 pathway is crucial for TH2 cell induction in vitro and in some in vivo models of TH2-associated disease, including allergen-induced AHR and T. muris infection48–50, this pathway is dispensable in other in vivo TH2 cell responses (see below).

Initial sources of IL-4 in vivo

IL-4, through its activation of STAT6, upregulates GATA3 expression8,9,17,51 and also suppresses TH1 and TH17 cell responses, partly through the upregulation of growth factor independent 1 (GFI1), a transcriptional repressor of IFNγ and IL-17 production52. Identifying the initial source of IL-4 is crucial to understanding the initiation of IL-4-dependent TH2 cell responses.

Natural killer T (NKT) cells produce large amounts of IL-4 immediately after TCR engagement53. However, mice lacking NKT cells such as CD1d- and β2-microglobulin-deficient mice can mount normal TH2 cell responses in various in vivo models, including those of helminth infections and induction of AHR54. A report showed that NKT cells were essential for allergen-induced AHR but were not required for TH2 cell differentiation in this model, implying that they orchestrate or mediate the effector response rather than TH2 cell induction55. These investigators have also reported that there are large numbers of NKT cells in the bronchial alveolar lavage fluid of patients with asthma, suggesting that NKT cell-derived cytokines may have an important role in human asthma56.

It has long been known that basophils produce large amounts of IL-4 when activated by FcεR1 cross-linking or through other cell surface receptors, both in mice57,58 and in humans59. Recent reports have shown that basophils transiently enter lymph nodes during immune responses to papain21 and that they are essential for IgE production and TH2 cell responses in mice immunized with papain30; however, whether IL-4 production is the sole or even main mechanism through which basophils induce these TH2 cell responses in vivo is still uncertain.

Naive CD4+ T cells can also produce IL-4 independently of IL-4 signalling when they are activated. In response to peptide stimulation, naive CD4+ T cells from TCR-transgenic IL-4Rα-deficient mice secrete amounts of IL-4 sufficient to induce TH2 cell differentiation, particularly when IFNγ and IL-12 are absent from the culture60. In vitro, autocrine and/or paracrine IL-4 induces and consolidates TH2 cell differentiation12,61, but whether it does so in vivo is not known.

IL-4-independent TH2 cell responses

Although the IL-4–IL-4R–STAT6 pathway is not essential for all forms of TH2 cell differentiation in vivo58,62–64, GATA3 activation is necessary17,51. TCR signalling may directly induce GATA3 expression, and this is particularly true when naive CD4+ T cells are stimulated in vitro with low concentrations of cognate peptide12,65,66 or with higher concentrations of altered peptide ligands67 (BOX 1). It is likely that low TCR signal strength also favours TCR-mediated induction of GATA3 expression in vivo and may result in IL-4-independent TH2 cell differentiation, although that has not been directly shown.

Other TH2 cell-promoting cytokines

In addition to IL-4, other cytokines, including TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33, have crucial roles in the induction of some TH2 cell responses in vivo. Depending on the TH2 cell-associated model under study, the relative importance of each cytokine varies, similar to the involvement of IL-4 in different settings. Below, we discuss the functions of these cytokines in allergen-induced TH2 cell responses, as well as during different helminth infections.

Functions of TSLP: initiation, amplification or both?

TSLP is produced by epithelial cells, mast cells and basophils21,28,68,69. Its expression is increased in the lungs of mice with airway inflammation, and lung-specific overexpression of TSLP induces TH2-related airway inflammation suggesting that TSLP can be an initiator of allergic airway inflammation68. In addition, treatment of human airway epithelial cells with IL-4 and IL-13 results in the upregulation of TSLP expression70, suggesting that an IL-4–TSLP or IL-13–TSLP loop may be involved in the amplification of TH2 cell responses (FIG. 2). Furthermore, the basophil-mediated TH2 cell response to papain is partially dependent on TSLP production by basophils21. During helminth infection, however, TSLP is only crucial for TH2 cell responses to some parasites (see below).

TSLP acts on CD4+ T cells, presumably through its activation of STAT5 (REFS 3,71,72). TSLPR-deficient mice fail to develop allergic responses to inhaled antigen; instead, these mice developed strong TH1 cell responses. Transferring wild-type CD4+ T cells into TSLPR-deficient mice restores their allergic responses, implying that the function of TSLP in this model is mainly through its direct action on CD4+ T cells73. A more recent study reported that TSLP has a crucial role in a TH2-mediated allergic skin inflammation model by acting exclusively on CD4+ T cells74. In TSLPR-deficient mice, there was decreased infiltration of eosinophils and less production of TH2 cell-associated cytokines in the skin. However, no widespread defect in DC maturation or in TH2 cell development was evident, suggesting that TSLP affects already differentiated TH2 cells to control their effector cytokine production. It has been recently reported that human CD4+ T cells express low levels of TSLPR and respond to TSLP poorly. The effects of IL-7 (which shares a receptor subunit with TSLP) on human CD4+ T cells are much more robust than those of TSLP in terms of inducing STAT5 phosphorylation and promoting T cell proliferation, suggesting the effects of TSLP on human CD4+ T cells are limited75. However, because much of the effect of TSLP may occur in tissues, a careful evaluation of CD4+ T cells from human skin, lung and gut for TSLPR expression is needed before a definitive conclusion on this important point is reached.

TSLP also acts on other immune cells. TSLP-treated human DCs produce TH2 cell-attracting chemokines, including CCL17 and CCL22 (REF. 28), that bind to CC-chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4), which is expressed by TH2 cells 76,77. These TSLP-treated DCs can also prime naive human CD4+ T cells to preferentially become TH2 cells28. TSLP-treated DCs upregulate OX40L cell surface expression and blockade of the OX40L–OX40 interaction diminishes TH2 cell cytokine production induced by TSLP-treated DCs in vitro45. Although OX40L–OX40 interaction is important for TH2 cell responses, TH1 cell responses may also require OX40L–OX40 interaction; all activated T cells upregulate OX40 expression. However, it is possible that the signalling triggered by OX40L has a unique role in promoting TH2 cell differentiation in the absence of IL-12 (REF. 45). Given that TSLP also suppresses IL-12 production by DCs, this may be the main mechanism through which TSLP biases DCs towards inducing TH2-type responses45,78,79. However, in the presence of CD40L–CD40 signalling, TSLP can still stimulate human DCs to induce TH2 cell differentiation without blocking IL-12 production, suggesting TSLP also affects other DC functions80. TSLP produced by epithelial cells also activates mast cells81. Interestingly, TSLP has been reported to increase the number of IL-4-producing basophils in the peripheral blood36, which may have an important role in certain TH2 cell responses.

In contrast to the need for TSLP in allergic airway inflammation, it is not required for TH2 cell responses to some helminths, such as Heligmosomoides polygyrus and N. brasiliensis. TSLPR-deficient mice have normal TH2 cell differentiation and protective immunity against these parasites78. However, TSLP is required for TH2-type immune responses to T. muris, possibly through its suppression of TH1 cell responses, as neutralization of IL-12 or IFNγ reverses the defect in TH2 cell responses in TSLPR-deficient mice78,79. Intestinal DCs from IEC-specific conditional Ikkb-knockout mice infected with T. muris produce higher levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and the IL-12 and IL-23 subunit p40, which correlates with the increased IFNγ and IL-17 production by CD4+ T cells from these mice27, suggesting that a cytokine (or several cytokines) produced by IECs (possibly TSLP) has an important role in regulating DC function.

Thus, TSLP can regulate the functions of T cells, DCs, mast cells and basophils in allergic responses and helminth infections. The relative importance of TSLP on the function of each cell type may vary in individual TH2-associated models, where the potential TH1 or TH17 cell response varies and thus the need to repress them.

Functions of IL-25: initiation, amplification or both?

IL-25 is an IL-17-related cytokine produced by TH2 cells82. Administration of recombinant IL-25 to naive mice induces IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 production and systemic TH2 cell responses, including IL-4-mediated IgE induction, IL-5-mediated eosinophilia and IL-13-mediated histopathological changes in lungs and gastrointestinal tracts82. Interestingly, IL-25 also induces eosinophilia and histopathological changes in recombination-activating gene (Rag)-knockout mice, which is consistent with the ability of IL-25 to promote IL-5 and IL-13 production by MHC class IIhiCD11clowF4/80lowCD4−CD8− NBNT cells82. IL-4 induction by IL-25 occurs in wild-type but not Rag-knockout mice, indicating that IL-25 induction of IL-4 production requires B and/or T cells. It has been recently reported that adipose tissue-associated LIN−KIT+SCA1+IL-7Rα+ NBNT cells produce IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-2 plus IL-25 stimulation83. Such cells are present in Rag-knockout mice but not in mice deficient for the common cytokine receptor γ-chain (γc), and these cells are crucial for IL-13-mediated goblet cell hyperplasia83.

IL-25-deficient mice infected with N. brasiliensis show delayed worm expulsion and induction of IL-5 and/or IL-13, whereas administration of IL-25 results in accelerated worm expulsion through the induction of TH2-associated cytokines made by KIT+FcεRI− NBNT cells84. Whether the NBNT cells capable of producing TH2-associated cytokines that were reported by three groups82–84 are the same population requires further investigation. Furthermore, whether such cells can be APCs during TH2-type immune responses to allergens or helminth products is not known. Interestingly, administration of IL-25 induces worm expulsion in Rag1-knockout mice infected with N. brasiliensis84, suggesting that the IL-25-responsive cell population may serve as effector cells and IL-4 and/or IL-13 production by TH2 cells may not be essential. Therefore, IL-25 produced by epithelial cells may initiate TH2-type immune responses by activating innate immune cells, and IL-25 produced by TH2 cells further boosts such an effect.

IL-25-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background fail to expel T. muris, correlating with a decreased TH2- and increased TH1-type response85. Blocking IL-12 and IFNγ in these mice restores their TH2-type response to T. muris and results in worm expulsion. Conversely, administration of IL-25 to AKR mice, which are normally susceptible to T. muris, conveys resistance to infection by the helminth, indicating that IL-25 has an important role in regulating the balance between TH1- and TH2-type responses during parasite infections.

IL-25 is also expressed by allergen-activated epithelial cells and it can directly act on CD4+ T cells to initiate TH2 cell differentiation in an IL-4-dependent manner86. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7) produced by airway epithelial cells during allergic inflammation dramatically increases the activity of IL-25 by cleaving it87. Mmp7-knockout mice have less AHR, which correlates with reduced TH2-type cytokine production in response to allergen challenge, suggesting IL-25 cleavage by MMP7 may be important for AHR induction.

Activated human basophils, eosinophils and mast cells express IL-25, which can upregulate GATA3 expression in human memory TH2 cells. Increased IL-25 and IL-25R expression have been detected in patients with asthma suggesting that IL-25 may serve as an amplification factor in human allergic diseases88.

Functions of IL-33: initiation, amplification or both?

IL-33 is a member of the IL-1 family89; one component of its receptor, ST2 (also known as IL-1RL1), is selectively expressed by the TH2 subset of TH cells90,91. Administration of IL-33 to naive mice induces splenomegaly, eosinophilia, increased serum IgE, IL-5 and IL-13 production, and histopathological changes in lungs and gastrointestinal tract89. Blocking IL-33 function by an ST2 fusion protein decreases eosinophilic airway inflammation, which is positively correlated with a decrease in IL-4 and IL-5 expression91. Although some strains of ST2-deficient mice displayed substantial reduction in pulmonary granuloma formation in response to SEA injection, consistent with reduced IL-5 expression and eosinophil infiltration in these mice92, other strains of ST2-deficient mice cleared N. brasiliensis infection normally93.

IL-33 is upregulated during the early phase of T. muris infection, and administration of IL-33 results in increased TSLP production94. IL-33 together with IL-3 can directly act on human basophils to induce IL-4 production95,96 and IL-33 has also been shown to activate mast cells97. IL-13 induces ST2 expression by macrophages and IL-33, in turn, promotes further differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages98. Furthermore, stimulation of TH2 cells with IL-33 together with TSLP or other STAT5 activators results in TCR-independent IL-13 production99. Adipose tissue-associated LIN−KIT+SCA1+IL-7Rα+ NBNT cells also express ST2 and they produce IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-33 (REF. 83). Therefore, IL-33 can initiate and amplify TH2-type responses under certain circumstances.

Thus, IL-4, TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33 are all associated with certain types of TH2-associated immune responses. In the model of TH2-associated inflammation discussed above, one or more of these cytokines produced by epithelial cells or basophils in response to allergens or helminth These cytokines products initiates TH2 cell differentiation. are also involved in the amplification of TH2-type immune responses at later stages by forming positive feedback loops. The cell sources, target cells and the functions of TH2-inducing cytokines are summarized in TABLE 1.

Table 1.

Cytokines involved in the initiation and amplification of TH2-type immune responses

| Cytokine | Induced by | Main source | Main targets | Functions related to TH2-type immune responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | Antigen12,60,61, IPSE25, IgE29, IL-2 (REF. 1), IL-3 (REF. 29), IL-4 (REF. 1), IL-25 (REF. 86) and TSLP71–75 | Naive CD4+ T cells12,60,61, TH2 cells1, NKT cells53 and basophils21,25,29,30,57–59 | T cells6,7, B cells107,108, macrophages109 and epithelial cells22,70 | Induction of TH2-associated cytokines6,7, IgE class switching107,108, alternative macrophage activation109 and induction of TSLP expression22,70 |

| IL-2 | Antigen3 | Activated CD4+ T cells3 | T cells3 | Induction of IL-4 (REFS 15,16), IL-4Rα3 and IL-2Rα3 expression |

| TSLP | Allergens21, helminth-derived products27, IL-4 and IL-13 (REFS 22,70) | Epithelial cells19,22,27,28,68–70, basophils21,69 and mast cells28,69 | DCs28,45,75, T cells71–75, basophils36 and mast cells81 | Suppression of IL-12 production45,78–80 and induction of TH2-associated cytokines 71,72 |

| IL-25 | Allergens19,86, helminth-derived products84,85 and IL-4 (REF. 82) | TH2 cells 82, epithelial cells19,86, basophils88, eosinophils88 and mast cells88 | T cells86 and NBNT cells82–84 | Induction of TH2-associated cytokines82,84,86 |

| IL-33 | Allergens19 and helminth-derived products94 | Epithelial cells19,110, endothelial cells110, airway smooth muscle cells111 and adipocytes112 | TH2 cells 90,91,99, DCs113, basophils95,96, mast cells97, macrophages98,114 and NBNT cells83 | Induction of TH2-associated cytokines89,91,95,96,99, TSLP expression94 and amplification of alternatively activated macrophages98 |

DC, dendritic cell; IL, interleukin; IPSE, IL-4-inducing principle of Schistosoma mansoni eggs; NBNT, non-B non-T; NKT, natural killer T; TH2, T helper 2; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

Putting the ‘TH2 pieces’ together

In vivo functions of IL-4 and TSLP

Both TSLP and IL-4 seem to be important for allergen-induced TH2-type immune responses (FIG. 3). TH2 cell differentiation in response to infection with some parasites, including N. brasiliensis, can occur in a TSLP- or IL-4-independent manner but TH2-type responses to other helminths, such as T. muris, require TSLP and IL-4. It remains to be determined to what extent TH2-type responses that are either IL-4- or TSLP-independent can occur in the absence of both these cytokines.

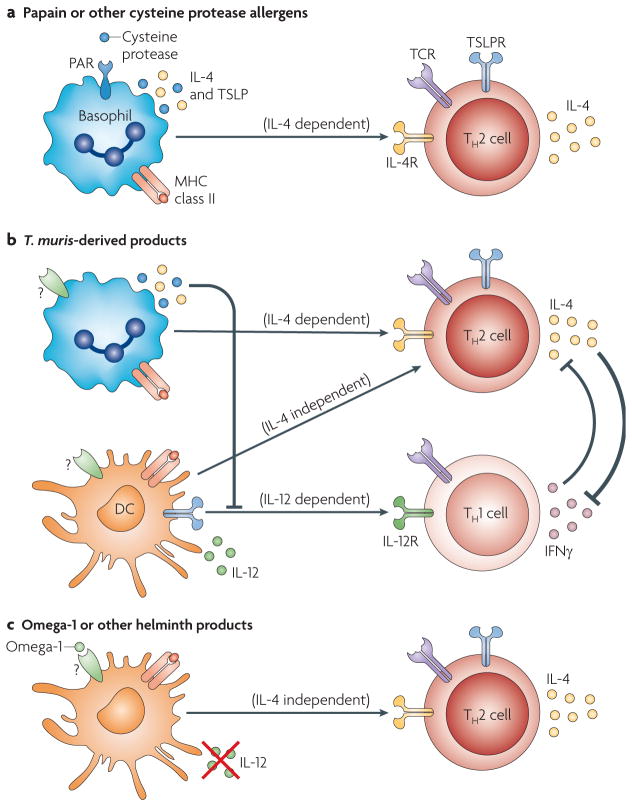

Figure 3. Basophils and dendritic cells, functioning as antigen-presenting cells, are differentially involved in various TH2-type immune responses.

Both basophils and dendritic cells (DCs) are involved in the fate determination of naive CD4+ T cells through cytokine production and antigen presentation; however, the relative importance of these two cell types seem to be different in various models. a | In papain-induced (and possibly other cysteine protease allergen-induced) T helper 2 (TH2)-type responses, basophils seem to be crucial, whereas DCs are not essential. Interleukin-4 (IL-4) and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), produced by activated basophils, are important for such TH2 cell differentiation. b | Different Trichuris muris-derived products may simultaneously activate basophils and DCs. Basophils are predominantly involved in TH2 cell induction, whereas DCs induce both TH1 and TH2 cell differentiation. TSLP produced by basophils may be required for suppressing IL-12 production by DCs, promoting the development of TH2 cell-inducing DCs and inducing IL-4 production by T cells. IL-4 produced either by basophils or T cells is also crucial for inhibiting interferon-γ (IFNγ) production in T cells and amplifying TH2-type responses. c | In some helminth infection models, helminth products including omega-1 can down-modulate the functions of activated DCs and suppress IL-12 production; therefore, IL-4-independent TH2 cell differentiation occurs without the involvement of basophils. TH2-type responses to Nippostrongylus brasiliensis do not require basophils, and such responses are both IL-4 and TSLP independent. PAR, protease-activated receptor; R, receptor; TCR, T cell receptor.

The mouse genetic background influences the initiation of TH1- and TH2-type immune responses (BOX 2). It is known that the balance between IL-4 and IFNγ production determines the resistance or susceptibility of different mouse strains to infection with T. muris. Blocking IL-4 in resistant mice results in a failure of worm expulsion, whereas blocking IFNγ or administration of recombinant IL-4 to susceptible mice induces TH2-type responses and parasite expulsion 48. Therefore, the initiation of TH2-type responses to infection with particular parasites or to allergen exposure differs, possibly because some stimuli that can induce TH2-type responses may also contain components capable of inducing TH1- or TH17-type responses. Simultaneous induction of TH1-, TH2- and TH17-associated responses of different magnitudes in various models results in a differential requirement of certain TH2 cell-inducing factors in the control of TH2-type responses. In cases in which mixed TH1, TH2 and TH17 cell-associated responses are triggered, TSLP and IL-4 may be required to suppress TH1- and TH17-type responses so that a preferential TH2-type response can occur. However, when TH2-type responses are already dominant during initial T cell activation, TSLP and IL-4 may no longer be crucial for TH2 cell differentiation. Changes in the balance of cytokines with cross-regulatory activities (such as IL-4 versus IFNγ, IL-4 versus TGFβ and TSLP versus IL-12) may result in changes of the type of immune responses induced. Therefore, when studying a TH2-type response, other types of responses should also be assessed at the same time.

Box 2. Genetic background influences TH2-type immune responses.

The genetic background of the mice used in models of T helper 2 (TH2)-mediated inflammation has an important role in determining the balance of the TH cell responses. One striking example is the response to Leishmania major infection103. C57BL/6 mice develop a protective TH1-type response but BALB/c mice are susceptible owing to a TH2-biased immune response. Many gene loci involved in TH2-type responses have been identified, one of which is the MYC-induced nuclear antigen (Mina) locus on chromosome 16. MINA is expressed at higher levels in many TH1-biased mice strains, including C57BL/6 mice, than in TH2-biased mice such as BALB/c mice104. MINA binds to the Il4 promoter and represses IL-4 production. Therefore, genetically determined differential expression levels of MINA at an early stage of CD4+ T cell activation may influence the balance between TH1 and TH2 cells. Responses to infection with some helminths such as Trichuris muris also vary among mouse strains. C57BL/6 mice are resistant to T. muris infection owing to the development of protective TH2 cell responses, whereas AKR mice are susceptible because of bias towards TH1 cell responses. The molecule (or molecules) responsible for such a difference remains to be determined.

In vivo functions of basophils and DCs

Basophils have a crucial role in sensing cysteine protease antigens, such as papain (FIG. 3a). However, in response to other TH2-inducing factors, the main function of basophils may be to regulate the balance of TH1 and TH2 cell responses (FIG. 3b). Although DCs can induce both TH1 and TH2 cell responses, basophils seem to function specifically as TH2-promoting APCs. Therefore, basophils are needed to induce more TH2 cells in the models in which TH1 cells are also induced by IL-12-producing DCs. It is also possible that basophils, through TSLP expression, suppress IL-12 production by DCs and/or promote the development of TH2-related DCs. However, if DCs are already conditioned to induce TH2 cell responses, such as in response to the S. mansoni product omega-1, basophils may no longer be essential (FIG. 3c). In this regard, basophils are not crucial APCs during TH2-type responses to T. muris infection when TH1 cell-inducing factors are blocked, and these cells are not essential for TH2-type responses to N. brasiliensis infection38, which are also IL-4 and TSLP independent.

The strength of T cell signalling and the cytokine milieu are two crucial determinants for TH2 cell differentiation. Freshly isolated DCs expressing low levels of MHC class II and B7 molecules (also known as CD80 and CD86) preferentially induce TH2 cell differentiation, whereas TH1 cell differentiation is driven by activated IL-12-producing DCs100. DCs treated with omega-1 do not produce IL-12 and display a resting phenotype. Thus, TH2 cell differentiation occurs when CD4+ T cells receive low-strength TCR signalling, consistent with many in vitro studies. Low levels of MHC class II expression on basophils, in addition to their production of IL-4 and TSLP, may also contribute to the ability of basophils to preferentially induce TH2 cell differentiation.

Conclusions and perspective

The products of allergens and helminths, as the initiators of TH2-type immune responses, are crucial in determining the activation of their target cells and the production of TH2-promoting cytokines by these stimulated cells. Many different cell types, including lung and intestinal epithelial cells, DCs and basophils, are responsible for sensing these products and thus involved in the initiation of TH2-type immune responses in vivo. The initiation of TH2-type responses takes place in the tissue sites where allergens or parasites are encountered. Activated DCs and basophils migrate from tissues to the draining lymph nodes to stimulate proliferation and differentiation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. The amplification of TH2-type responses starts in the lymph nodes when naive CD4+ T cells begin to differentiate towards TH2 cells and continues to occur until the differentiated TH2 cells reach the tissue sites to orchestrate immune responses. At that stage, TH2 cells may directly communicate with epithelial cells and many types of immune cells that are recruited to the tissue sites to further regulate the magnitude of the TH2-type responses. Crosstalk among different cells participating in TH2-type responses through the production of TH2-related cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-25, TSLP and IL-33, results in powerful feedback loops. When over-produced, each of these cytokines can initiate TH2-type responses. In response to allergens or helminths, each of these cytokines can make some contribution to the overall TH2 cell responses but the relative importance of each and the signalling pathways that are induced may vary in different models. In some TH2-associated models, such as T. muris infection in resistant or susceptible mouse strains, the combination of TSLP, IL-25, IL-33 and IL-4 becomes crucial in determining the initiation of the TH2 cell response. Whether T. muris is less efficient than other helminths in inducing TH2-type responses or it is more potent than others in triggering TH1-type responses is not certain; therefore, although valuable, data from T. muris infection studies may not represent the overall principles of in vivo TH2-type immune responses.

The molecular mechanisms for TH2 cell differentiation in vivo are poorly understood. Both GATA3 expression and STAT5 activation are crucial for the initiation of TH2 cell differentiation in vitro. However, TH2 cell differentiation can occur even when GATA3 is expressed at low levels but a strong STAT5 signal is provided. As IL-4 is the only factor known to induce high levels of GATA3 expression in vitro and TH2 cell differentiation often occurs in vivo in the absence of IL-4, it is crucial to determine GATA3 expression levels in TH2 cells generated in vivo in various models. If GATA3 expression is high in TH2 cells that develop in the absence of IL-4 in vivo, then what is inducing GATA3 expression and how? However, it remains possible that the expression GATA3 need not be upregulated especially for IL-4-independent TH2-type responses, although it is essential for these responses. If GATA3 is not upregulated in an IL-4-independent TH2-type response in vivo, focus should then be on studying the regulation of STAT5 activators, such as IL-2, IL-7 and TSLP, and their actions on T cells, which may be a key event for the initiation of TH2-type immune responses.

Future studies should also focus on the molecular mechanisms through which allergens and helminths are sensed by innate immune cells, including epithelial cells and basophils, through which TH2-inducing cytokines IL-4, TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33 are induced in these stimulated innate cells. Understanding the molecular basis for the initiation of TH2 cell differentiation and the cross-regulation between TH2- and other TH-type responses will greatly enhance our ability to design immune interventions and to treat many TH2-related diseases, such as allergic inflammation and chronic parasite infections.

Note added in proof

Two recent reports115,116 on further studies of the IL-25-responsive NBNT cells have shown that these cells are important during the initiation and amplification of TH2-type responses and that they also function as effector cells. By using an Il13–enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) reporter mouse strain, McKenzie and colleagues115 showed that the NBNT cells (designated ‘nuocytes’) comprise 80% of the IL-13-producing cells that are induced in mice treated with IL-25 or IL-33. These cells express inducible T cell co-stimulator (ICOS), ST2, IL-17RB and IL-7Rα, although only a fraction of them express KIT. Nuocytes are induced during helminth infection through the action of IL-25 and IL-33. Such cells enhance T cell responses in an IL-13-independent manner and their expansion requires T cells. By contrast, IL-13 production by these cells is crucial for accelerating worm expulsion. By using KIT and Il4–eGFP as markers, Artis and colleagues116 reported that IL-25 induces both KIT+GFP− and KIT+GFP+ NBNT cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissues. Interestingly, these NBNT cells expressed no or low levels of ST2 and variable levels of IL-7Rα. IL-25-induced KIT+ cells promote TH2-type responses in vivo and rescue the TH2 cell defects in IL-25-deficient mice in response to T. muris infection. IL-25-induced KIT+GFP+ cells give rise only to mast cells after in vitro culture with stem cell factor and IL-3, whereas KIT+GFP− cells can generate mast cells, basophils, macrophages and other CD11b+ cells. KIT+GFP− but not KIT+GFP+ cells express MHC class II molecules and can induce IL-4Rα-mediated TH2 cell differentiation in vitro, suggesting these cells may also be TH2 cell-inducing APCs.

Acknowledgments

The work is supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the US National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- Asthma

A chronic disease of the lung, characterized by airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation. The most common form of the disease, allergic asthma, results from inappropriate immune responses to common allergens in genetically susceptible individuals. Allergic asthma is characterized by infiltration of the airway wall with mast cells, lymphocytes and eosinophils. CD4+ T cells producing TH2-type cytokines are thought to have a crucial role in orchestrating the recruitment and activation of these effector cells of the allergic response

- Airway hyperresponsiveness

Increased narrowing of the airways, initiated by exposure to a defined stimulus that usually has little or no effect on airway function in normal individuals. This is a defining physiological characteristic of asthma

- Non-B non-T cells

(NBNT cells). Cells that are different from basophils, eosinophils, mast cells and NKT cells and can produce IL-5 and IL-13 but little or no IL-4 in response to IL-25 or IL-33 stimulation. They may produce IL-4 in response to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) plus ionomycin stimulation. These cells were described as MHC class IIhiCD11clow F4/80lowCD4−CD8− or KIT+FcεRI− or LIN−KIT+SCA1+IL-7Ra+ST2+ in three different reports, and they may comprise three different cell types

- WNT

A signalling mediator named both for its mutant phenotype in Drosophila melanogaster (Wingless) and for its role as a preferential retrovirus integration site in murine leukaemia virus-induced leukaemias (Int-1). WNT signalling activates the T cell factor 1 (TCF1) and lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1) families of transcription factors by stabilizing their co-activator β-catenin and mobilizing it from the cytoplasm to the nucleus

- Cysteine proteases

Enzymes requiring a cysteine thiol in their catalytic pockets to cleave polypeptides by hydrolysis of the peptide bonds. Common cysteine proteases include papain and bromelain

- β2-microglobulin

(β2m). A single immunoglobulin-like domain that non-covalently associates with the main polypeptide chain of MHC class I molecules. In the absence of β2m, MHC class I molecules are unstable and are therefore found at low levels at the cell surface

- Altered peptide ligands

(APLs). Peptide analogues that are derived from the original antigenic peptide. They commonly have amino acid substitutions at TCR-contact residues. TCR engagement by these APLs usually leads to partial or incomplete T cell activation. Antagonistic APLs can specifically antagonize and inhibit T cell activation that is induced by the wild-type antigenic peptide

- Recombination-activating gene (Rag)-knockout mice

Rag1 and Rag2 are expressed by developing lymphocytes. Mice that are deficient in either RAG protein fail to produce B and T cells owing to a developmental block in the gene rearrangement that is required for receptor expression

- Alternatively activated macrophage

A macrophage stimulated by IL-4 or IL-13 that expresses arginase 1, the mannose receptor and IL-4Rα. There may be pathogen-associated molecular patterns expressed by helminths that can also drive the alternative activation of macrophages

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATABASES

UniProtKB: http://www.uniprot.org

amphiregulin | GATA3 | GFI1 | IL-3 | IL-4 | IL-5| IL-9 | IL-13 | IL-24 | IL-25 | IL-33 | ST2 | STAT5A | STAT6 | TSLP

FURTHER INFORMATION

William E. Paul’s homepage: http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/labs/aboutlabs/li/generalImmunologySection/paul.htm

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

Contributor Information

William E. Paul, Email: wpaul@niaid.nih.gov.

Jinfang Zhu, Email: jfzhu@niaid.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Zhu J, Paul WE. CD4 T cells: fates, functions, and faults. Blood. 2008;112:1557–1569. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pestka S, et al. Interleukin-10 and related cytokines and receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:929–979. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by γc family cytokines. Nature Rev Immunol. 2009;9:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:5771–5777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-21: basic biology and implications for cancer and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:57–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Gros G, Ben-Sasson SZ, Seder R, Finkelman FD, Paul WE. Generation of interleukin 4 (IL-4)-producing cells in vivo and in vitro: IL-2 and IL-4 are required for in vitro generation of IL-4-producing cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:921–929. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swain SL, Weinberg AD, English M, Huston G. IL-4 directs the development of Th2-like helper effectors. J Immunol. 1990;145:3796–3806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang DH, Cohn L, Ray P, Bottomly K, Ray A. Transcription factor GATA-3 is differentially expressed in murine Th1 and Th2 cells and controls Th2-specific expression of the interleukin-5 gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21597–21603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21597. References 8 and 9 are the first two papers to describe GATA3 as the master regulator of TH2 cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurata H, Lee HJ, O’Garra A, Arai N. Ectopic expression of activated Stat6 induces the expression of Th2-specific cytokines and transcription factors in developing Th1 cells. Immunity. 1999;11:677–688. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu J, Guo L, Watson CJ, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. Stat6 is necessary and sufficient for IL-4’s role in Th2 differentiation and cell expansion. J Immunol. 2001;166:7276–7281. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamane H, Zhu J, Paul WE. Independent roles for IL-2 and GATA-3 in stimulating naive CD4+ T cells to generate a Th2-inducing cytokine environment. J Exp Med. 2005;202:793–804. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amsen D, et al. Direct regulation of Gata3 expression determines the T helper differentiation potential of Notch. Immunity. 2007;27:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Q, et al. T cell factor 1 initiates the T helper type 2 fate by inducing the transcription factor GATA-3 and repressing interferon-γ. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:992–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cote-Sierra J, et al. Interleukin 2 plays a central role in Th2 differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3880–3885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400339101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu J, Cote-Sierra J, Guo L, Paul WE. Stat5 activation plays a critical role in Th2 differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:739–748. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu J, et al. Conditional deletion of Gata3 shows its essential function in TH1–TH2 responses. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/ni1128. References 12, 15, 16 and 17 have established the importance of both GATA3 expression and STAT5 activation during both TH2 cell differentiation and lineage commitment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenbarth SC, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-enhanced, Toll-like receptor 4-dependent T helper cell type 2 responses to inhaled antigen. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1645–1651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammad H, et al. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nature Med. 2009;15:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trompette A, et al. Allergenicity resulting from functional mimicry of a Toll-like receptor complex protein. Nature. 2009;457:585–588. doi: 10.1038/nature07548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sokol CL, Barton GM, Farr AG, Medzhitov R. A mechanism for the initiation of allergen-induced T helper type 2 responses. Nature Immunol. 2008;9:310–318. doi: 10.1038/ni1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouzaki H, O’Grady SM, Lawrence CB, Kita H. Proteases induce production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by airway epithelial cells through protease-activated receptor-2. J Immunol. 2009;183:1427–1434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinfelder S, et al. The major component in schistosome eggs responsible for conditioning dendritic cells for Th2 polarization is a T2 ribonuclease (omega-1) J Exp Med. 2009;206:1681–1690. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Everts B, et al. Omega-1, a glycoprotein secreted by Schistosoma mansoni eggs, drives Th2 responses. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1673–1680. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schramm G, et al. Cutting edge: IPSE/α-1, a glycoprotein from Schistosoma mansoni eggs, induces IgE-dependent, antigen-independent IL-4 production by murine basophils in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178:6023–6027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okano M, Satoskar AR, Nishizaki K, Harn DA., Jr Lacto-N-fucopentaose III found on Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens functions as adjuvant for proteins by inducing Th2-type response. J Immunol. 2001;167:442–450. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaph C, et al. Epithelial-cell-intrinsic IKK-β expression regulates intestinal immune homeostasis. Nature. 2007;446:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature05590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soumelis V, et al. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:673–680. doi: 10.1038/ni805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshimoto T, et al. Basophils contribute to TH2-IgE responses in vivo via IL-4 production and presentation of peptide–MHC class II complexes to CD4+ T cells. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:706–712. doi: 10.1038/ni.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sokol CL, et al. Basophils function as antigen-presenting cells for an allergen-induced T helper type 2 response. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:713–720. doi: 10.1038/ni.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kool M, et al. Alum adjuvant boosts adaptive immunity by inducing uric acid and activating inflammatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:869–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambrecht BN, Salomon B, Klatzmann D, Pauwels RA. Dendritic cells are required for the development of chronic eosinophilic airway inflammation in response to inhaled antigen in sensitized mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:4090–4097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambrecht BN, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells induce Th2 responses to inhaled antigen, leading to eosinophilic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:551–559. doi: 10.1172/JCI8107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang D, Biragyn A, Hoover DM, Lubkowski J, Oppenheim JJ. Multiple roles of antimicrobial defensins, cathelicidins, and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin in host defense. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:181–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang D, et al. Eosinophil-derived neurotoxin acts as an alarmin to activate the TLR2–MyD88 signal pathway in dendritic cells and enhances Th2 immune responses. J Exp Med. 2008;205:79–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perrigoue JG, et al. MHC class II-dependent basophil-CD4+ T cell interactions promote TH2 cytokine-dependent immunity. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:697–705. doi: 10.1038/ni.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Else KJ, Grencis RK. Antibody-independent effector mechanisms in resistance to the intestinal nematode parasite. Trichuris muris Infect Immun. 1996;64:2950–2954. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2950-2954.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S, et al. Cutting edge: basophils are transiently recruited into the draining lymph nodes during helminth infection via IL-3, but infection-induced Th2 immunity can develop without basophil lymph node recruitment or IL-3. J Immunol. 184:1143–1147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902447. References 29, 30, 36 and 38 report that basophils are TH2 cell-inducing APCs in some but not all in vivo TH2-associated models. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Taking our breath away: dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of asthma. Nature Rev Immunol. 2003;3:994–1003. doi: 10.1038/nri1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kapsenberg ML. Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. Nature Rev Immunol. 2003;3:984–993. doi: 10.1038/nri1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agrawal S, et al. Cutting edge: different Toll-like receptor agonists instruct dendritic cells to induce distinct Th responses via differential modulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Fos. J Immunol. 2003;171:4984–4989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balic A, Harcus Y, Holland MJ, Maizels RM. Selective maturation of dendritic cells by Nippostrongylus brasiliensis-secreted proteins drives Th2 immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3047–3059. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kane CM, et al. Helminth antigens modulate TLR-initiated dendritic cell activation. J Immunol. 2004;173:7454–7461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amsen D, et al. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ito T, et al. TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1213–1223. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacDonald AS, Maizels RM. Alarming dendritic cells for Th2 induction. J Exp Med. 2008;205:13–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steinman RM. Lasker Basic Medical Research Award. Dendritic cells: versatile controllers of the immune system. Nature Med. 2007;13:1155–1159. doi: 10.1038/nm1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Else KJ, Finkelman FD, Maliszewski CR, Grencis RK. Cytokine-mediated regulation of chronic intestinal helminth infection. J Exp Med. 1994;179:347–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohn L, Homer RJ, Marinov A, Rankin J, Bottomly K. Induction of airway mucus production by T helper 2 (Th2) cells: a critical role for interleukin 4 in cell recruitment but not mucus production. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1737–1747. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohn L, Tepper JS, Bottomly K. IL-4-independent induction of airway hyperresponsiveness by Th2, but not Th1, cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:3813–3816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pai SY, Truitt ML, Ho IC. GATA-3 deficiency abrogates the development and maintenance of T helper type 2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1993–1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308697100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu J, et al. Downregulation of Gfi-1 expression by TGF-β is important for differentiation of Th17 and CD103+ inducible regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:329–341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshimoto T, Paul WE. CD4pos, NK1.1pos T cells promptly produce interleukin 4 in response to in vivo challenge with anti-CD3. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1285–1295. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown DR, et al. Beta 2-microglobulin-dependent NK1.1+ T cells are not essential for T helper cell 2 immune responses. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1295–1304. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akbari O, et al. Essential role of NKT cells producing IL-4 and IL-13 in the development of allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Nature Med. 2003;9:582–588. doi: 10.1038/nm851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akbari O, et al. CD4+ invariant T-cell-receptor+ natural killer T cells in bronchial asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1117–1129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seder RA, et al. Mouse splenic and bone marrow cell populations that express high-affinity Fcε receptors and produce interleukin 4 are highly enriched in basophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2835–2839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Min B, et al. Basophils produce IL-4 and accumulate in tissues after infection with a Th2-inducing parasite. J Exp Med. 2004;200:507–517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacGlashan D, Jr, et al. Secretion of IL-4 from human basophils. The relationship between IL-4 mRNA and protein in resting and stimulated basophils. J Immunol. 1994;152:3006–3016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noben-Trauth N, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. Conventional, naive CD4+ T cells provide an initial source of IL-4 during Th2 differentiation. J Immunol. 2000;165:3620–3625. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noben-Trauth N, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. IL-4 secreted from individual naive CD4+ T cells acts in an autocrine manner to induce Th2 differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1428–1433. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1428::AID-IMMU1428>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jankovic D, et al. Single cell analysis reveals that IL-4 receptor/Stat6 signalling is not required for the in vivo or in vitro development of CD4+ lymphocytes with a Th2 cytokine profile. J Immunol. 2000;164:3047–3055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Finkelman FD, et al. Stat6 regulation of in vivo IL-4 responses. J Immunol. 2000;164:2303–2310. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Voehringer D, Shinkai K, Locksley RM. Type 2 immunity reflects orchestrated recruitment of cells committed to IL-4 production. Immunity. 2004;20:267–277. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Constant S, Pfeiffer C, Woodard A, Pasqualini T, Bottomly K. Extent of T cell receptor ligation can determine the functional differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1591–1596. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tao X, Constant S, Jorritsma P, Bottomly K. Strength of TCR signal determines the co-stimulatory requirements for Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 1997;159:5956–5963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tao X, Grant C, Constant S, Bottomly K. Induction of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells by antigenic peptides altered for TCR binding. J Immunol. 1997;158:4237–4244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou B, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin as a key initiator of allergic airway inflammation in mice. Nature Immunol. 2005;6:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/ni1247. This report, together with reference 28, describes a possible role for TSLP in the initiation of allergic TH2-type responses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu YJ. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: master switch for allergic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:269–273. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kato A, Favoreto S, Jr, Avila PC, Schleimer RP. TLR3- and Th2 cytokine-dependent production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:1080–1087. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Al-Shami A, et al. A role for thymic stromal lymphopoietin in CD4+ T cell development. J Exp Med. 2004;200:159–168. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Isaksen DE, et al. Requirement for stat5 in thymic stromal lymphopoietin-mediated signal transduction. J Immunol. 1999;163:5971–5977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Al-Shami A, Spolski R, Kelly J, Keane-Myers A, Leonard WJ. A role for TSLP in the development of inflammation in an asthma model. J Exp Med. 2005;202:829–839. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.He R, et al. TSLP acts on infiltrating effector T cells to drive allergic skin inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11875–11880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801532105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu N, Wang YH, Arima K, Hanabuchi S, Liu YJ. TSLP and IL-7 use two different mechanisms to regulate human CD4+ T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2111–2119. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. Flexible programs of chemokine receptor expression on human polarized T helper 1 and 2 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bonecchi R, et al. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and chemotactic responsiveness of type 1 T helper cells (Th1s) and Th2s. J Exp Med. 1998;187:129–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Massacand JC, et al. Helminth products bypass the need for TSLP in Th2 immune responses by directly modulating dendritic cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13968–13973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906367106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Taylor BC, et al. TSLP regulates intestinal immunity and inflammation in mouse models of helminth infection and colitis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:655–667. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081499. References 78 and 79 report that TSLP is important for TH2-type responses to T. muris but not other helminth infections. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Watanabe N, et al. Human TSLP promotes CD40 ligand-induced IL-12 production by myeloid dendritic cells but maintains their Th2 priming potential. Blood. 2005;105:4749–4751. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Allakhverdi Z, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is released by human epithelial cells in response to microbes, trauma, or inflammation and potently activates mast cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:253–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fort MM, et al. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity. 2001;15:985–995. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moro K, et al. Innate production of TH2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit+Sca-1+ lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fallon PG, et al. Identification of an interleukin (IL)-25-dependent cell population that provides IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 at the onset of helminth expulsion. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1105–1116. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051615. References 82–84 describe IL-25-responsive NBNT cells that can produce TH2-associated cytokines, especially IL-5 and IL-13. These cells may be crucial during many TH2-type responses in vivo. However, whether all these cells are the same population requires further study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Owyang AM, et al. Interleukin 25 regulates type 2 cytokine-dependent immunity and limits chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2006;203:843–849. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Angkasekwinai P, et al. Interleukin 25 promotes the initiation of proallergic type 2 responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1509–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Goswami S, et al. Divergent functions for airway epithelial matrix metalloproteinase 7 and retinoic acid in experimental asthma. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:496–503. doi: 10.1038/ni.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang YH, et al. IL-25 augments type 2 immune responses by enhancing the expansion and functions of TSLP-DC-activated Th2 memory cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1837–1847. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schmitz J, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. This paper reports that IL-33 is an important TH2-inducing cytokine and one of its receptor subunit is ST2, which is selectively expressed by TH2 cells but not other TH cells as reported in references 90 and 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xu D, et al. Selective expression of a stable cell surface molecule on type 2 but not type 1 helper T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:787–794. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lohning M, et al. T1/ST2 is preferentially expressed on murine Th2 cells, independent of interleukin 4, interleukin 5, and interleukin 10, and important for Th2 effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6930–6935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Townsend MJ, Fallon PG, Matthews DJ, Jolin HE, McKenzie AN. T1/ST2-deficient mice demonstrate the importance of T1/ST2 in developing primary T helper cell type 2 responses. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1069–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoshino K, et al. The absence of interleukin 1 receptor-related T1/ST2 does not affect T helper cell type 2 development and its effector function. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1541–1548. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Humphreys NE, Xu D, Hepworth MR, Liew FY, Grencis RK. IL-33, a potent inducer of adaptive immunity to intestinal nematodes. J Immunol. 2008;180:2443–2449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pecaric-Petkovic T, Didichenko SA, Kaempfer S, Spiegl N, Dahinden CA. Human basophils and eosinophils are the direct target leukocytes of the novel IL-1 family member IL-33. Blood. 2009;113:1526–1534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Suzukawa M, et al. An IL-1 cytokine member, IL-33, induces human basophil activation via its ST2 receptor. J Immunol. 2008;181:5981–5989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Allakhverdi Z, Smith DE, Comeau MR, Delespesse G. Cutting edge: the ST2 ligand IL-33 potently activates and drives maturation of human mast cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:2051–2054. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kurowska-Stolarska M, et al. IL-33 amplifies the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages that contribute to airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6469–6477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guo L, et al. IL-1 family members and STAT activators induce cytokine production by Th2, Th17, and Th1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13463–13468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906988106. This paper reports that IL-33 can induce IL-13 production by TH2 cells in a TCR-independent manner. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stumbles PA, et al. Resting respiratory tract dendritic cells preferentially stimulate T helper cell type 2 (Th2) responses and require obligatory cytokine signals for induction of Th1 immunity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2019–2031. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hosken NA, Shibuya K, Heath AW, Murphy KM, O’Garra A. The effect of antigen dose on CD4+ T helper cell phenotype development in a T cell receptor-αβ-transgenic model. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1579–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Constant SL, Bottomly K. Induction of Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cell responses: the alternative approaches. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]