Abstract

Although researchers argue that single parents perceive more work-family conflict than married parents, little research has examined nuances in such differences. Using data from the 2002 National Study of Changing Workforce (N = 1,430), this study examines differences in home-to-job conflict by marital status and gender among employed parents. Findings indicate that single mothers feel more home-to-job conflict than single fathers, married mothers, and married fathers. Some predictors of home-to-job conflict vary by marital status and gender. Job pressure is related to home-to-job conflict more for single parents than for married parents. Age of children is related to conflict for single fathers only. Whereas an unsupportive workplace culture is related to conflict, especially for married fathers, the lack of spouses’ share of domestic responsibilities is related to conflict, especially for married mothers. These findings indicate that marital status and gender create distinct contexts that shape employed parents’ perceived home-to-job conflict.

Keywords: employed parents, home-to-job conflict, gender, marital status, single parents, work-family conflict

The increase in women’s labor force participation in the latter half of the 20th century has led to great interest among researchers and policy makers in understanding people’s perceptions of work-family conflict—the extent to which people find it difficult to balance work and family responsibilities (Bellavia & Frone, 2005). Much research has investigated specific job and family characteristics that are related to work-family conflict (for reviews, see Bellavia & Frone, 2005; Frone, 2003). Among other characteristics, having minor children at home is a strong predictor of work-family conflict (e.g., Mennino, Rubin, & Brayfield, 2005). Although researchers, policy makers, and the public have been particularly concerned about whether single parents are successfully meeting the dual demands of paid work and family responsibilities (Heymann, 2000), surprisingly little research has systematically investigated whether and how work-family conflict differs between single and married parents.

Researchers tend to argue that single parents may feel more work-family conflict than married parents because they must shoulder the dual demands of paid work and family responsibilities with fewer resources (Avison, Ali, & Walters, 2007; Hertz, 1999). Prior research is unclear, however, whether the resource deficit of single parents is due to the lack of a partner or due to other factors such as a lower socioeconomic status (Kendig & Bianchi, 2008). Furthermore, research on marital status, gender, and parenting behavior has suggested the importance of considering the intersection of marital status and gender when trying to understand distributions of job and family demands among parents (Hook & Chalasani, 2008; Risman, 1998). Little is known, however, about whether single fathers differ from single mothers in home-to-job conflict. In addition, although most researchers focus on differences in the levels of work-family conflict, the predictors of work-family conflict may differ by marital status and gender.

This paper contributes to scholarly work on work-family conflict by examining how the intersection of marital status and gender is related to different levels and predictors of work-family conflict among employed parents, using data from the 2002 National Study of Changing Workforce (NSCW). Between two forms of work-family conflict—i.e., job-to-home conflict and home-to-job conflict (Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1992)—this paper focuses on home-to-job conflict because home-to-job conflict has been less investigated than job-to-home conflict (Dilworth, 2004). Additionally, marital status, a family characteristic, may be more relevant to home-to-job conflict than to job-to-home conflict (Frone, 2003). Drawing on marital status, gender, and parenting behavior research, I argue that parents’ sense of home-to-job conflict is uniquely influenced by the intersection of marital status and gender.

PREDICTORS OF HOME-TO-JOB CONFLICT

Work-family conflict refers to cognitive appraisals that involve the extent to which individuals feel that demands in the paid work domain interfere with their ability to meet demands in the family domain (i.e., job-to-home conflict) or the extent to which demands in the family domain interfere with the ability to meet demands in the paid work domain (i.e., home-to-job conflict) (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Voydanoff, 2005a). As mentioned earlier, this paper focuses on home-to-job conflict. It is important to investigate factors leading to a higher level of home-to-job conflict because it relates to negative outcomes such as absenteeism from work, tardiness, poor job performance, job dissatisfaction, and distress (Frone, 2003; Grzywacz & Bass, 2003).

Voydanoff (2005a) has argued that the fit between demands (e.g., time, strain, and expectations) and resources (e.g., money, instrumental and emotional support, and sense of control) within and between the domains of work and family affects the degree of conflict people feel in balancing work and family lives. Previous studies have identified several family demands and resources that are related to home-to-job conflict. For example, having a larger number of children or having young children at home is related to more home-to-job conflict (Dilworth, 2004; Mennino, Rubin, & Brayfield, 2005). Although time with children is typically conceptualized as a demand (Voydanoff, 2005a), little research has examined how it is related to home-to-job conflict. Time for housework is also conceptualized as a demand, but a previous study did not find its relationship to home-to-job conflict (Stevens, Minnotte, Mannon, & Kiger, 2007). Perhaps whether a spouse or someone else shares daily routines of housework and child care, rather than the amount of time spent on them, may influence the degree of family demands that parents perceive. Perceived support from family and friends—whether parents feel they have access to support for a problem—is an important resource that makes a difference in how easily parents cope with multiple demands (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000).

Although some researchers do not conceptualize job characteristics as direct predictors of home-to-job conflict (see Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1992, as an example of the “domain-specific model”), Voydanoff (2005b) has emphasized that job characteristics can be directly related to home-to-job conflict because of the “boundary-spinning” nature of demands and resources between the work and family domains. For example, parents with greater time demands at paid work may feel greater home-to-job conflict (Voydanoff, 2005b), albeit some studies found this association only for women (Dilworth, 2004; Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). Parents who often take work home, whose jobs require frequent overnight travel, or who feel greater pressure to increase productivity may feel it difficult to meet the required job demands because of their family (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; Voydanoff, 2005b). In contrast, the workplace may provide parents with resources that can be used to cope with demands (Voydanoff, 2005b). Higher earnings allow parents to hire outside help for child care or household chores to reduce daily hassles (Hertz, 1999). How intrinsic job rewards, such as job autonomy and job creativity, relate to home-to-job conflict has been debated. For example, job autonomy or job creativity can be related to less conflict because these job characteristics lead to a greater sense of control that can be used to cope with demanding job aspects (Voydanoff, 2005a). Autonomous or creative jobs, however, tend to provide more responsibilities in the workplace, which can make individuals feel as if their family obligations keep them from devoting as much time and energy as they wish to their job (Schieman, McBrier, & Van Gundy, 2003). Finally, a family-friendly workplace culture may help parents feel less conflict (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; Mennino, Rubin, & Brayfield, 2005; Voydanoff, 2005b).

MARITAL STATUS, GENDER, AND HOME-TO-JOB CONFLICT AMONG PARENTS

As reviewed above, much research has investigated specific family and job characteristics that are related to home-to-job conflict. Despite scientific and policy debates over whether single parents are successfully meeting their dual demands of paid work and family life (Heymann, 2000), little research has focused on how single parents differ from married parents in home-to-job conflict. In some studies, single parents and single adults without minor children were combined as one group (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; Mennino, Rubin, & Brayfield, 2005; Schieman, McBrier, & Van Gundy, 2003), in spite of the marked differences in the levels of family demands between the two groups. Other studies showed that single parents felt more home-to-job conflict than married parents at the descriptive level, but did not further examine the differences at the multivariate level (Avison, Ali, & Walters, 2007; Bellavia & Frone, 2005). Using a Canadian sample, Duxbury, Higgins, and Lee (1994) found no differences in home-to-job conflict between single and partnered parents. Further, McManus, Korabik, Rosin, and Kelloway (2002) found that lower family income was associated with more home-to-job conflict for single mothers than for partnered mothers, suggesting that predictors of home-to-job conflict may differ by marital status. Very little is known about how single fathers differ from other parents in home-to-job conflict. This paper is among the first to assess how the interception of marital status and gender uniquely shapes the levels and the predictors of home-to-job conflict among employed parents.

Differences in Levels of Home-to-Job Conflict

According to Voydanoff’s (2005a) framework, differences in the levels of home-to-job conflict among single mothers, single fathers, married mothers, and married fathers can be accounted for by different levels of demands and resources in the work and family domains among the four groups of parents. Research on marital status, gender, and parenting behavior may help explain such differences. For example, an explanation emphasizes that the structural position of being a lone parent in the household creates higher levels of family demands for single parents than for married parents (Risman & Park, 1988). Not having a spouse is also related to fewer resources in the form of social support. Although some qualitative studies emphasized that single parents can build support networks with family and friends that would compensate for the lack of spouse support (Hertz, 1999), quantitative evidence has indicated that because reciprocity is the norm in social support networks, single parents, who have fewer resources to contribute, may have less access to support networks than married parents (Hogan, Hao, & Parish, 1990). Thus, levels of home-to-job conflict should be similar between single mothers and single fathers and between married mothers and married fathers and higher for single than married parents.

Other research, however, has emphasized the role of gender in determining parents’ family and job demands. Despite the increase in non-traditional gender attitudes, mothers in dual-earner marriages tend to reduce job demands in order to deal with greater family demands, whereas fathers in dual-earner marriages tend to take greater responsibilities for job demands and scale back their family involvement (Moen & Yu, 2000). Single mothers reduce paid work hours to attend to their children, despite their breadwinning role (Hertz, 1999; 2006). In contrast, single fathers are more likely than single mothers to receive help from female relatives or friends with daily housework and child care routines (Hilton, Desrochers, & Devall, 2001). Thus, the idea of primacy of gender suggests that single mothers and married mothers should show similar levels of home-to-job conflict. In addition, single fathers and married fathers should show similar levels of home-to-job conflict. Regarding gender differences in the levels of home-to-job conflict, prior research is inconsistent. Some studies have indicated that women feel more home-to-job conflict than men (Dilworth, 2004; Duxbury et al., 1994; Mennino et al., 2005; Voydanoff, 2005b) because of greater family demands; however, other studies found little gender difference (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; Gutek, Searle, & Klepa, 1991), perhaps because men have greater job demands than women, and greater job demands are related to more home-to-job conflict, which may offset gender differences in home-to-job conflict.

In her study of single fathers, Risman (1998) concluded that the structural position in the household or gender alone could not fully explain parents’ perceptions of breadwinning and caregiving responsibilities. Her argument has been echoed by other researchers who also found that parental time allocations and parenting behaviors were uniquely influenced by the intersection of marital status and gender. For example, Hook and Chalasani (2008) found that single fathers spent less time in paid work and more time with children than married fathers; however, they spent more time in paid work and less time with children than married or single mothers. Hawkins, Amato, and King (2006) also found that single fathers were more likely than married fathers, but less likely than single or married mothers, to be involved in a wide range of children’s activities. Similarly, studies found that single mothers, although more likely than single fathers to cut back paid work demands to attend to children, spent less time in routine housework and more time in paid work than married mothers (Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, 2006; Hook & Chalasani, 2008). These studies suggest the importance of the intersection of marital status and gender in shaping parents’ work-family experiences. Thus, in this study, based on the most recent scholarship on marital status, gender, and parenting, I expect that single mothers, single fathers, married mothers, and married fathers will show different levels of home-to-job conflict, with single mothers feeling the highest level of conflict followed by single fathers, married mothers, and married fathers. These differences will disappear, however, when the levels of demands and resources in the family and job domain are taken into account.

Differences in Predictors of Home-to-Job Conflict

Although researchers have largely focused on differences in the levels of home-to-job conflict by social status, predictors of home-to-job conflict may differ by social status. Duxbury and Higgins (1991), for example, found that predictors of work-family conflict differed by gender. Studies combining identity theory with stress research indicate the degree to which individuals perceive certain role responsibilities as demanding, or perceive certain role resources as scarce, may depend on the extent to which that role is salient to their primary identity (Thoits, 1991). This idea suggests that parents may feel more home-to-job conflict when demands in a less salient role are high because they do not assume responsibilities in the less salient role. As indicated earlier, research has found that the salience of breadwinning and nurturing roles varies by the intersection of gender and marital status (e.g., Hook & Chalasani, 2008). Because of the less salient caregiving responsibilities with higher levels of family demands (e.g., time with children), married fathers may feel more home-to-job conflict than the other three groups of parents. In contrast, because of the less salient breadwinning role, with higher levels of paid work demands (e.g., taking work home, job pressure), married mothers may feel more home-to-job conflict than the other three groups of parents. Regarding resources, parents may feel more home-to-job conflict when resources in a more salient role are low because they assume that they are responsible for the demands in the more salient role and how easily they can handle the demands depends on the levels of resources within the more salient role domain. Thus, with lower levels of job resources (e.g., family-friendly workplace culture), married fathers may feel more home-to-job conflict than the other three groups of parents. In contrast, with lower levels of family resources (e.g., perceived social support), married mothers may feel more home-to-job conflict than the other three groups of parents.

Other Factors

The present analysis takes into account background characteristics that are related to the odds of being a single parent and the levels of home-to-job conflict. Single parenthood is concentrated among young and racial/ethnic minority parents (Kendig & Bianchi, 2008). Younger adults tend to report more home-to-job conflict than older adults, and Whites tend to report more conflict than non-Whites (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; Mennino et al., 2005; Schieman, McBrier, & Van Gundy, 2003). Single parents are more likely to be less educated than married parents (Kendig & Bianchi, 2008). Although a higher level of education is related to more home-to-work conflict (Mennino et al., 2005; Schieman, McBrier, & Van Gundy, 2003), it is also related to the extent that individuals have jobs with greater rewards (Ross & Reskin, 1992), which may be related to less home-to-job conflict.

METHOD

Sample

Data were drawn from the 2002 National Study of the Changing Workforce (NSCW) conducted by Harris Interactive and Families and Work Institute. The 2002 NSCW consists of 3,504 telephone interviews with adults aged 18 or older who were in the civilian labor force and resided in the contiguous 48 states. Calls were made to a stratified unclustered random probability sample generated by random-digit-dial methods. The response rate was about 52% (Bond, Thompson, Galinsky, & Prottas, 2003). The proposed study focused on parents who were living with children under age 18 at least six months per year (n = 1,444). Excluding those who did not answer marital status or home-to-job conflict (n = 14, 0.96%), the sample size is N = 1,430. Several variables had a very small percentage of missing data. To deal with these missing data, I performed a multiple imputation procedure described by Allison (2001). For time variables and annual earnings, to avoid the influence of extreme values, those who reported values above the 95th percentile were assigned the 95th percentile values.

Measures

The dependent variable was home-to-job conflict, measured as the mean response to five questions (α = .80) asking how often in the previous three months (a) their family or personal life kept them from doing as good a job at work as they could; (b) their family or personal life drained them of the energy they needed to do their job; (c) their family or personal life kept them from concentrating on their job; (d) they were not in as good a mood as they would like to be at work because of their personal or family life; and (e) they had not had enough time for their job because of their family (1 = never to 5 = very often).

The independent variable was the interaction of marital status and gender, measured as four dummy variables, including single mothers, single fathers, married mothers, and married fathers. Single parents included those who were separated, divorced, widowed, and never married. NSCW did not distinguish respondents who were married but not living together for reasons other than marital problems. Cohabiting parents (31 fathers and 48 mothers) were included in the married groups because this study focused on the structural aspect of marital status (i.e., the presence of a partner in the household). I examined the same analyses excluding cohabiting parents from the sample with very similar patterns of findings.

Family demands and resources

The number of children under age 18 living in the household ranged from 1 to 6. Age of the youngest child was measured as dummy variables, including ages < 6, ages 6 to 12, and ages 13 to 17. Time with children on workdays and time for housework on workdays were respondents’ self-reports and measured in hours. The degree of taking primary responsibilities in domestic work was the sum of the three questions that asked about three items of domestic work, “In your household, who takes the greatest responsibility for (a) cooking, (b) cleaning, and (c) routine care of children?” (0 = somebody else, including spouse, child, other relative, friend, or paid worker; 1 = respondent shares this responsibility about equally with his/her spouse/partner; 2 = respondent). Perceived support from family and friends was the average response to the two statements, (a) “I have the financial support I need from my family or friends when I have a money problem,” and (b) “I have the support I need from my family and friends when I have a personal problem” (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree).

Job demands and resources

Weekly paid work hours was measured by respondents’ self-report about a typical week. Overnight travel was measured by the number of overnight business trips in the past three months. Taking work home was measured by the question, “How often do you do any paid or unpaid work at home that is part of your job?” (1 = never to 5 = more than once a week). Job pressure was the average of the three statements (α = .53), (a) “My job requires that I work very fast”; (b) “My job requires that I work very hard”; and (c) “I never seem to have enough time to get everything done on my job” (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Job autonomy was the average of the four statements (α = .73), (a) “I have the freedom to decide what I do on my job”; (b) It is basically my own responsibility to decide how my job gets done”; (c) I have a lot of say about what happens on my job”; and (d) “I decide when I take breaks” (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Job creativity was the average of the four statements (α = .71), (a) “My job requires that I keep learning new things”; (b) “My job requires that I be creative”; (c) “The work I do on my job is meaningful to me”; and (d) “My job lets me use my skills and abilities” (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Annual earnings from all paid jobs in the previous year were measured in thousand dollar increments. Family-friendly workplace culture was the average of the four statements about the respondents’ workplace (α = .74), (a) “There is an unwritten rule that you cannot take care of family needs on company time”; (b) “Employees who put their family or personal needs ahead of their jobs are not looked on favorably”; (c) “If you have a problem managing your work and family responsibilities, the attitude at my place of employment is: ‘It’s the employee’s problem, not mine’”; and (d) “Employees have to choose between advancing in their jobs or devoting attention to their family or personal lives” (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree).

Control variables

Age was measured in years. Education was the highest level of schooling (1 = less than high school to 5 = advanced degree). Race/ethnicity was measured as a series of dummy variables, including White, Black, Hispanic, and other race.

Analytical Plan

First, using t-tests (two-tailed), I examined differences in family demands, family resources, job demands, job resources, and home-to-job conflict at the descriptive level among single mothers, single fathers, married mothers, and married fathers. Second, six ordinary-least-squares (OLS) regression models were conducted. Model 1 included control variables (i.e., background characteristics) only. Model 2 examined the associations between family demands and home-to-job conflict with control variables and whether differences in family demands would explain differences in home-to-job conflict among the four groups of parents. Model 3 examined the associations between family resources and home-to-job conflict, controlling for family demands and background characteristics, and whether differences in family resources would explain differences in home-to-job conflict among the four groups of parents. Model 4 examined the associations between job demands and home-to-job conflict with control variables, evaluating whether differences in job demands would explain differences in home-to-job conflict among the four groups of parents. Model 5 examined the associations between job resources and home-to-job conflictcontrolling for job demands and background characteristics. This model evaluated whether differences in job resources would explain differences in home-to-job conflict among the four groups of parents. Model 6 included all variables. Third, to examine whether predictors of home-to-job conflict vary by marital status and gender, interaction terms between each dummy variable of the four groups of parents and each family and job characteristic were included in Model 6. All analyses used weighted data.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The sample consisted of 16.6% single mothers, 4.4% single fathers, 38.6% married fathers, and 40.4% married mothers. As expected, the levels of demands and resources in the family and job domains, as well as home-to-job conflict, varied across the four groups of parents. Single parents, especially single fathers, have a fewer number of children under age 18 living in the household than married parents. Single fathers were less likely to have young children in their households, whereas married fathers were more likely to have young children. Mothers spent more time with children than fathers, regardless of marital status. Time for housework also showed a similar gender pattern, although single fathers spent more time doing housework than married fathers. Single mothers were least likely to have someone else take primary responsibility for cooking, cleaning, and routine care of children, followed by married mothers and then single fathers. Perceived support from family and friends was lower for single parents than married parents with little difference by gender within each group. Fathers worked longer hours than mothers for pay, whereas single mothers worked longer hours than married mothers. Single fathers worked as many hours as married fathers. Fathers had more overnight travel than mothers, and married fathers were more likely than single fathers to travel overnight. Single mothers reported less job pressure but also less job autonomy than other groups. Single mothers and single fathers reported less job creativity than married counterparts. Single mothers earned the least, whereas married fathers earned the most. Single fathers were less likely than single mothers to report a family-friendly work culture, whereas married mothers and married fathers were more likely than single mothers to report a family-friendly work culture. The average score for home-to-job conflict was 2.35 for single mothers, 2.23 for single fathers, 2.14 for married mothers, and 2.15 for married fathers (range = 1 to 5). T-tests indicated that single mothers had significantly higher levels of conflict than the other three groups of parents. The difference between single fathers and married mothers was significant at p <.05 level (result not shown), although the difference between single fathers and married fathers was not significant.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Variables for Total Sample and by Marital Status and Gender.

| Total Sample | Single Mothers | Single Fathers | Married Mothers | Married Fathers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age | 38.81 | (8.83) | 41.24 | (8.96) | 41.24 | (10.94)*** | 38.35 | (7.92)*** | 39.59 | (9.19)*** |

| Education (1–5) | 2.83 | (1.13) | 2.61 | (0.95) | 2.61 | (1.14)** | 2.99 | (0.98)*** | 2.79 | (1.31)** |

| White | 0.72 | (0.45) | 0.64 | (0.45) | 0.64 | (0.53) | 0.78 | (0.38)*** | 0.73 | (0.49)*** |

| Black | 0.12 | (0.33) | 0.26 | (0.41) | 0.26 | (0.49)*** | 0.07 | (0.23)*** | 0.10 | (0.33)*** |

| Hispanic | 0.11 | (0.31) | 0.04 | (0.27) | 0.04 | (0.22) | 0.12 | (0.30) | 0.12 | (0.36) |

| Other race | 0.04 | (0.20) | 0.06 | (0.20) | 0.06 | (0.26) | 0.03 | (0.16)** | 0.05 | (0.24) |

| Family Demands and Resources | ||||||||||

| Youngest child < 6 | 0.42 | (0.49) | 0.25 | (0.44) | 0.25 | (0.48)*** | 0.39 | (0.45) | 0.47 | (0.55)*** |

| Youngest child 6–12 | 0.36 | (0.48) | 0.48 | (0.44) | 0.48 | (0.55)* | 0.36 | (0.44)** | 0.33 | (0.52)*** |

| Youngest child 13–17 | 0.22 | (0.42) | 0.27 | (0.37) | 0.27 | (0.49)* | 0.25 | (0.40)* | 0.20 | (0.44) |

| Number of children < 18 | 1.95 | (1.03) | 1.68 | (0.88) | 1.68 | (0.85)* | 1.89 | (0.92)* | 2.07 | (1.18)*** |

| Daily time with children (in hours) | 2.91 | (1.93) | 2.42 | (1.90) | 2.42 | (1.87)*** | 3.40 | (1.90) | 2.45 | (1.82)*** |

| Daily time for housework (in hours) | 2.41 | (2.22) | 2.14 | (1.89) | 2.14 | (1.26)*** | 2.96 | (1.78) | 1.91 | (2.66)*** |

| Primary domestic responsibilities (0–6) | 3.27 | (2.31) | 4.71 | (1.34) | 4.71 | (1.93)*** | 4.96 | (1.25)*** | 1.32 | (1.48)*** |

| Support from family & friends (1–4) | 3.29 | (0.74) | 3.13 | (0.81) | 3.13 | (0.87) | 3.37 | (0.65)*** | 3.30 | (0.78)*** |

| Job Demands and Resources | ||||||||||

| Weekly work hours | 45.22 | (13.40) | 50.07 | (10.48) | 50.07 | (13.59)*** | 39.49 | (12.20)*** | 49.88 | (13.33)*** |

| Taking work home (1–5) | 2.28 | (1.50) | 1.94 | (1.26) | 1.94 | (1.49) | 2.39 | (1.39)*** | 2.33 | (1.68)*** |

| Number of overnight travel | 1.38 | (3.21) | 1.13 | (1.77) | 1.13 | (3.30)*** | 0.68 | (1.86) | 2.12 | (4.37)*** |

| Job pressure (1–4) | 2.95 | (0.72) | 3.11 | (0.72) | 3.11 | (0.66)*** | 2.92 | (0.67)*** | 3.00 | (0.75)*** |

| Job autonomy (1–4) | 3.07 | (0.78) | 3.04 | (0.75) | 3.04 | (0.93)* | 3.04 | (0.70)*** | 3.14 | (0.84)*** |

| Job creativity (1–4) | 3.47 | (0.59) | 3.41 | (0.60) | 3.41 | (0.61) | 3.46 | (0.54)*** | 3.51 | (0.62)*** |

| Annual earnings (in thousands) | 39.93 | (30.45) | 40.99 | (15.37) | 40.99 | (23.86)*** | 27.86 | (17.85)*** | 52.98 | (38.47)*** |

| Family-friendly culture (1–4) | 2.97 | (0.72) | 2.77 | (0.68) | 2.77 | (0.83)** | 3.07 | (0.65)*** | 2.93 | (0.78) |

| Home-to-Job conflict (1–5) | 2.18 | (0.74) | 2.23 | (0.72) | 2.23 | (0.89)** | 2.14 | (0.66)*** | 2.15 | (0.80)*** |

| N | 1,430 | 238 | 62 | 578 | 552 | |||||

Note. Differences between single mothers and each group of parents are significant at:

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 2 presents results from OLS regression models that examined differences in the levels of home-to-job conflict by marital status and gender. Single mothers were used as the omitted reference group because they showed the highest level of home-to-job conflict at the descriptive level. Model 1, which included background characteristics, indicates that higher levels of education were related to higher home-to-job conflict. Hispanic and other race were related to less home-to-job conflict compared with Whites. Controlling for background characteristics, there was little difference in home-to-job conflict between single fathers and single mothers, whereas married fathers and married mothers showed less home-to-job conflict than single mothers. Differences in home-to-job conflict among single fathers, married mothers, and married fathers were not significant.

Table 2.

Ordinary-Least-Squares Regression Analyses Predicting the Relationships Between the Intersection of Marital Status and Gender and Home-to-Job Conflict.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Marital Status and Gendera | ||||||||||||

| Single fathers | −.115 | (.100) | −.106 | (.101) | −.094 | (.100) | −.189 | (.099) | −.179 | (.099) | −.159 | (.098) |

| Married mothers | −.216 | (.064)*** | −.208 | (.064)** | −.175 | (.064)** | −.239 | (.063)*** | −.226 | (.062)*** | −.193 | (.062)** |

| Married fathers | −.190 | (.062)** | −.061 | (.083) | −.032 | (.082) | −.265 | (.062)*** | −.221 | (.063)*** | −.073 | (.080) |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age | −.002 | (.002) | −.005 | (.003) | −.006 | (.003)* | −.002 | (.002) | .000 | (.002) | −.003 | (.003) |

| Education | .037 | (.019)* | .039 | (.019)* | .049 | (.019)** | −.006 | (.020) | .015 | (.021) | .021 | (.021) |

| Blacka | .032 | (.063) | .030 | (.064) | −.008 | (.063) | .044 | (.062) | −.016 | (.062) | −.041 | (.062) |

| Hispanica | −.160 | (.065)* | −.165 | (.065)* | −.198 | (.064)** | −.128 | (.064)* | −.163 | (.064)* | −.192 | (.064)** |

| Other racea | −.225 | (.097)* | −.229 | (.096)* | −.266 | (.095)** | −.200 | (.094)* | −.233 | (.094)* | −.264 | (.094)** |

| Family Demands | ||||||||||||

| Youngest child < 6a | −.016 | (.050) | −.007 | (.049) | −.002 | (.048) | ||||||

| Youngest child 13–17a | .060 | (.057) | .055 | (.056) | .075 | (.054) | ||||||

| Number of children < 18 | .054 | (.020)** | .049 | (.020)* | .047 | (.020)* | ||||||

| Daily time with children | −.023 | (.012) | −.020 | (.012) | −.010 | (.012) | ||||||

| Daily time for housework | −.002 | (.015) | −.002 | (.015) | −.006 | (.014) | ||||||

| Primary domestic responsibilities | .040 | (.014)** | .040 | (.014)** | .040 | (.014)** | ||||||

| Family Resources | ||||||||||||

| Support from family & friends | −.156 | (.027)*** | −.115 | (.027)*** | ||||||||

| Work Demands | ||||||||||||

| Weekly work hours | .000 | (.002) | .001 | (.002) | .001 | (.002) | ||||||

| Taking work home | .035 | (.015)* | .050 | (.016)** | .045 | (.016)** | ||||||

| Overnight travel | .018 | (.006)** | .020 | (.006)** | .018 | (.006)** | ||||||

| Job pressure | .204 | (.028)*** | .179 | (.029)*** | .165 | (.029)*** | ||||||

| Work Resources | ||||||||||||

| Annual earnings | −.002 | (.001)* | −.002 | (.001) | ||||||||

| Job autonomy | .022 | (.028) | .032 | (.028) | ||||||||

| Job creativity | −.081 | (.037)* | −.060 | (.037) | ||||||||

| Family-friendly culture | −.136 | (.031)*** | −.133 | (.031)*** | ||||||||

| Intercept | 2.351 | (.107)*** | 2.218 | (.156)*** | 2.722 | (.176)*** | 1.791 | (.133)*** | 2.349 | (.184)*** | 2.476 | (.288)*** |

| R2 | .022*** | .035*** | .058*** | .077*** | .102*** | .125*** | ||||||

Omitted groups were single mothers, White, and youngest child 6–12.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Model 2, which included family demands, indicates that having more children was related to more home-to-job conflict, but age of the youngest child was not related to home-to-job conflict. Neither time with children nor time for housework was related to home-to-job conflict. The greater degree of taking primary responsibilities in cooking, cleaning, and child care was related to more home-to-job conflict. When family demands variables were added, differences in home-to-job conflict between married fathers and single mothers became nonsignificant, indicating that married fathers would have felt as much conflict as single mothers if they had shouldered the same level of family demands as single mothers. Only married mothers continued to show lower home-to-job conflict than single mothers. Model 3 added a family resource variable, perceived support from family and friends, which was related to less home-to-job conflict. By adding this variable, the coefficients for married mothers declined 16% (i.e., [1 − (−.175/−.208)] × 100), although remained significant, suggesting that if single mothers had the same levels of perceived support from family and friends as married mothers, the gap in home-to-job conflict between the two groups would have been smaller.

Turning to job characteristics, paid work hours was not related to home-to-job conflict, but taking work home, overnight travel, and job pressure were related to higher home-to-job conflict (Model 4). By adding job demands, the size of coefficients for married mothers and for married fathers increased 11% and 39% (from Model 1 to Model 4), respectively, suggesting that if single mothers had the same levels of job demands as married mothers or married fathers, they would have reported even greater home-to-job conflict. Model 5 added job resources to Model 4. Higher levels of earnings, job creativity, and a family-friendly culture were related to less home-to-job conflict. From Model 4 to Model 5, the size of coefficients for married mothers and married fathers declined 5% and 17%, respectively, indicating that if single mothers had the same level of job resources as married mothers or married fathers, the gaps in home-to-job conflict would have been smaller. Note that without controlling for family characteristics, the coefficient for married fathers remained significant and negative, suggesting that the differences in home-to-job conflict between married fathers and single mothers were attributed more to family characteristics than to job characteristics. Differences between single mothers and married mothers also remained significant. Model 6 shows a full model, adding family demands and family resources to Model 5. It shows that, controlling for background characteristics, family demands, family resources, job demands, and job resources, there were no differences in home-to-job conflict between single mothers and single fathers and between single mothers and married fathers; however, married mothers showed less home-to-job conflict than single mothers.

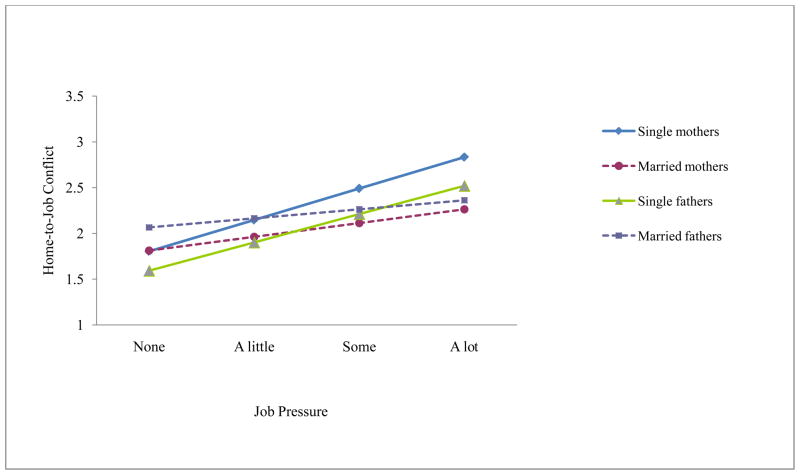

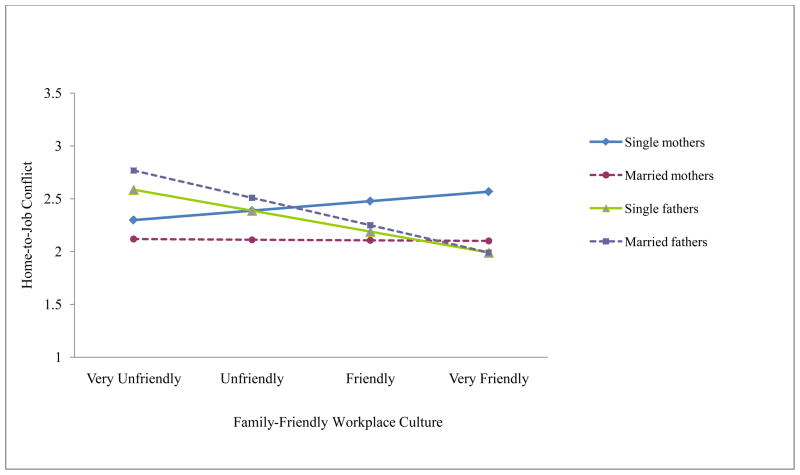

The final sets of analyses examined whether predictors of home-to-job conflict differ by marital status and gender, using interaction terms between each of the four groups of parents and each of the family and job characteristics on home-to-job conflict. Table 3 presents the results for interaction terms that were statistically significant (the complete model is available from the author). To interpret the significant interaction terms, I calculated predicted means for home-to-job conflict for the four groups of parents. Due to page limitation, only two of the six significant results are presented in Figures (the other four figures are available from the author). With these supplemental analyses, I interpreted the results as follows: The coefficient for the interaction of the youngest child aged 13–17 x single fathers was significant and positive. It appears that having older children was related to more home-to-job conflict for single fathers only. The degree of taking primary domestic responsibilities was related to higher home-to-job conflict for married parents, especially for married mothers, but not for single parents. Job pressure was related to higher home-to-job conflict for single mothers and single fathers than for married mothers and married fathers (Figure 1). Job autonomy was related to higher home-to-job conflict for single fathers and married mothers than for single mothers and married fathers. Job creativity was related to lower home-to-job conflict, except for married fathers. Finally, a family-friendly workplace culture was related to less home-to-job conflict for fathers, especially married fathers, whereas it was not related to home-to-job conflict for mothers. Specifically, as shown in Figure 2, among those whose workplaces were very unsupportive, married fathers showed the highest level of home-to-job conflict; however, among those whose workplaces were very supportive, married fathers, along with single fathers and married mothers, showed a lower level of home-to-job conflict than single mothers.

Table 3.

Ordinary-Least-Squares Regression Analyses Assessing Differences in Predictors of Home-to-Job Conflict by Marital Status and Gender among Employed Parents (N = 1,430).

| b | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Family Demands | ||

| Youngest child 13–17 x single fathers | .722 | (.256)** |

| Youngest child 13–17 x married mothers | .145 | (.163) |

| Youngest child 13–17 x married fathers | .060 | (.160) |

| Primary domestic responsibilities x single fathers | .017 | (.065) |

| Primary domestic responsibilities x married mothers | .103 | (.043)* |

| Primary domestic responsibilities x married fathers | .079 | (.042) |

| Job Demands | ||

| Job pressure x single fathers | −.034 | (.193) |

| Job pressure x married mothers | −.193 | (.086)* |

| Job pressure x married fathers | −.244 | (.085)** |

| Job Resources | ||

| Job autonomy x single fathers | .327 | (.137)* |

| Job autonomy x married mothers | .172 | (.085)* |

| Job autonomy x married fathers | .035 | (.081) |

| Job creativity x single fathers | −.275 | (.211) |

| Job creativity x married mothers | .083 | (.110) |

| Job creativity x married fathers | .287 | (.106)** |

| Family-friendly culture x single fathers | −.288 | (.174) |

| Family-friendly culture x married mothers | −.096 | (.102) |

| Family-friendly culture x married fathers | −.348 | (.091)*** |

| R2 | .186*** | |

Note: Omitted reference groups are each of explanatory variables x single mothers. Models include the main effects of all explanatory variables in Model 6 in Table 2 and interaction terms between marital status/gender and each explanatory variable.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Job Pressure and Home-to-Job Conflict by Marital Status and Gender

Figure 2.

Family-Friendly Workplace Culture and Home-to-Job Conflict by Marital Status and Gender

DISCUSSION

Although researchers tend to contend that single parents experience more work-family conflict than married parents, little research has investigated systematically as to how marital status, in conjunction with gender, is related to employed parents’ sense of work-family conflict. This paper advances our understanding of variations in the levels and predictors of work-family conflict by the intersection of marital status and gender, focusing on home-to-job conflict.

As expected, levels of home-to-job conflict vary by the intersection of marital status and gender, with single mothers feeling greater home-to-job conflict than single fathers, married fathers, and married mothers. After controlling for background characteristics, such as age, education, and race/ethnicity, differences in home-to-job conflict between single mothers and single fathers disappeared; however, differences between single mothers and married mothers and fathers remained. The higher level of conflict for single mothers than for married fathers was largely because of greater family demands for single mothers than for married fathers. The difference in home-to-job conflict between single and married mothers was for a different reason—it was partly because of fewer resources such as perceived social support from family and friends. This makes sense, because the majority of dual-earner mothers take primary responsibilities in domestic work (Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, 2006); thus, differences between married and single mothers in housework and child care demands may not be substantial. As found in prior research (e.g., Hogan, Hao, & Parish, 1990), it appears that single parents have less access to reliable social support than married parents. Even after taking background, family, and job characteristics into account, married mothers showed less home-to-job conflict than single mothers, suggesting that some other factors that were not examined in this paper may explain the differences. One important caveat in interpreting the lower level of home-to-job conflict for married mothers is a selection bias. Married mothers are more likely than other groups of parents to be out of the labor force—i.e., to be out of the sample—when they experienced high work-family conflict (Blair-Loy, 2003; Schieman, Milkie, & Glavin, 2009). Thus, the average score of home-to-job conflict for married women found in the present analysis might be underestimated. Regardless, findings suggest that having a spouse at home is a resource that is related to fewer family demands (especially for men) and more support from others to cope with demands, which is related to lower home-to-job conflict.

Findings also indicate that some predictors of home-to-job conflict vary among the four groups of parents, although not always in an expected manner. The extent to which their spouse shares responsibilities for daily domestic work matters more for married mothers’ home-to-job conflict than for the three other groups of parents. This is somewhat in support of the prediction that resources in a more salient role matter because the spouses’ share of domestic responsibilities could be conceptualized as greater resources (rather than fewer demands). This finding is consistent with other research findings that partnership in the division of household labor plays an important role in influencing perceived work-family conflict for dual-earner parents, especially mothers (Hochschild, 1989; Moen & Yu, 2000; Stevens et al., 2007). Married fathers showed different patterns than the three other groups of parents in the associations of job resources to home-to-job conflict. First, as expected, married fathers feel more home-to-job conflict than other parents when the workplace is insensitive to employees’ family needs. There is qualitative evidence in support of this finding that a workplace culture is especially relevant for married fathers’ sense of work-family conflict. Married fathers feel more barriers to asking for workplace support for their family responsibilities than other parents because bosses and coworkers tend to assume that married fathers are not the primary caregivers in their households (Gerson, 1993; Levin & Pittinsky, 1997). Second, unexpectedly, job creativity is related to less home-to-job conflict for other parents, but not for married fathers. As reviewed earlier, prior research has suggested that a creative job, which tends to lead to a higher sense of control, may play a role as coping resources that can be used to deal with stressfulness of work-family demands (Voydanoff, 2005a); however, it also may be related to a higher sense of home-to-job conflict because it provides individuals with more responsibilities in the job domain (Schieman, McBrier, & Van Gundy, 2003). Because of a higher salience of employment and breadwinning role, married fathers may be more likely than the other three groups of parents to show the latter case.

A few other findings reflect different life contexts shaped by the intersection of marital status and gender, although unpredicted. Single fathers are more likely than other parents to feel conflict when they have older children. Prior research has indicated that single fathers are less likely than other parents to live with their children when their children are younger, perhaps because of cultural beliefs that young children need maternal care (Hook & Chalasani, 2008). Because of the lack of experience juggling paid work and caring for young children, single fathers may perceive having teenage children more demanding than do other parents. The findings on variations in the relationships between job autonomy and home-to-job conflict by marital status and gender are harder to interpret. Given the ongoing discussions as to the conceptualization of the role of intrinsic job rewards in shaping home-to-job conflict (Schieman, McBrier, & Van Gundy, 2003), further research is needed to interpret these findings.

One finding indicates marital status effects, not the intersection of marital status and gender effects. With the same levels of job pressure, single mothers and fathers feel more home-to-job conflict than married mothers and fathers. This finding is consistent with findings of some qualitative studies, which found that single parents often face difficult times when their employers require them to work overtime, because it is more challenging for them than for married parents to find someone who can watch their children with a short notice (Heymann, 2000; Levin & Pittinsky, 1997). Another interesting finding for single parents is that whereas having help from their spouses for domestic responsibilities is related to lower levels of home-to-job conflict for married parents, particularly for married mothers, having help from children, relatives, or nonrelatives for domestic responsibilities does not seem to reduce single parents’ sense of home-to-job conflict. This finding is consistent with previous findings of ethnographic studies that emphasize the persistent, powerful notion of the two-parent heterosexual nuclear family as a normative family form (Hertz, 2006; Nelson, 2006). Single parents may rely on other people for family responsibilities when they have to, but they still believe that a spouse or partner is the “proper” person who “should” share work and family obligations with them. In other words, help from people other than a spouse or partner may not be perceived as resources that fully reduce the sense of burden of responsibilities that single parents feel in their households.

Altogether, the findings suggest that single mothers, single fathers, married mothers, and married fathers may perceive not only different levels of work-family conflict but also different family and job characteristics as stressful or helpful in combining paid work and family responsibilities. These findings inform work-family researchers who consider marital status or gender alone may overlook the ways that the intersection of marital status and gender creates unique experiences of work-family conflict for parents. For example, previous findings of inconsistencies in gender differences in work-family conflict may be because those studies did not account for the intersection of marital status and gender. The present study also informs policy makers and employers about the importance of understanding the issues that are unique to and shared among people in different family types. Job pressure, an unsupportive workplace culture, and a lower level of perceived social support are all good predictors of home-to-job conflict. Whereas a lower level of perceived social support is an issue that is common across the four groups of parents, job pressure is especially an issue for single parents, and an unsupportive workplace culture is especially an issue for married fathers. Such nuanced knowledge should be useful to promote workplaces that are responsive to employees’ work-family life in the era of diverse family forms.

The present analysis has limitations that future research should address. Because of the lack of longitudinal data, the causal directions are unclear. The present analysis did not distinguish among continuously married parents, cohabiting parents, and remarried parents. Research has shown, however, that couple dynamics and family interactions differ among those in first marriages, cohabitation, and remarriages (Seltzer, 2000; Sweeney, 2010), suggesting that parents in these different contexts might face different challenges in work-family integration. In addition, past research has suggested that spouses’ emotional support and marital quality, rather than marital status per se, are critical factors influencing home-to-job conflict (Bellavia & Frone, 2005), although this study was unable to examine these factors because of the lack of information about single parents’ relationship quality with non-resident parents. Future research is warranted to further understand the challenges and strategies in employed parents’ work-family lives that may vary by family context and gender.

In conclusion, findings underscore that the intersection of gender and marital status creates distinct contexts that can lead to different constraints facing parents when integrating paid work with family responsibilities. Parents in different positions by marital status and gender vary not only in objective levels of demands and resources, but also in subjective meanings of demands and resources, in the family and job domains. Given the increased diversity of U.S. families, it would be simplistic if researchers and employers assumed that distributions and perceptions of demands and resources in the family and job domains are uniform across employed parents in diverse family contexts.

Acknowledgments

I thank I-Fen Lin, Jan Reynolds, and John Woo for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. I also acknowledge the National Center for Family & Marriage Research at Bowling Green State University for its assistance.

References

- Allison PD. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Avison WR, Ali J, Walters D. Family structure, stress, and psychological distress: A demonstration of the impact of differential exposure. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:301–317. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavia GM, Frone MR. Work-family conflict. In: Barling J, Kelloway EK, Frone MR, editors. Handbook of work stress. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- Blair-Loy M. Competing devotions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, Milkie MA. Changing rhythms of American family life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bond JT, Thompson C, Galinsky E, Prottas D. Highlights of the 2002 National Study of the Changing Workforce. New York: Families and Work Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth JEL. Predictors of negative spillover from family to work. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury LE, Higgins CA. Gender differences in work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1991;76:60–74. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury L, Higgins C, Lee C. Work-family conflict: A comparison by gender, family type, and perceived control. Journal of Family Issues. 1994;15:449–466. [Google Scholar]

- Frone M. Work-family balance. In: Quick JC, Tetrick LE, editors. Handbook of occupational health psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Associations; 2003. pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1992;77:65–78. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerson K. No man’s land: Men’s changing commitments to family and work. New York: Basic Books; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review. 1985;10:76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Bass BL. Work, family, and mental health: Testing different models of work-family fit. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:248–262. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Marks NF. Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5:111–126. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutek B, Searle S, Klepa L. Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1991;76:560–568. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DN, Amato PR, King V. Parent-adolescent involvement: The relative influence of parent gender and residence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz R. Single by chance, mothers by choice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz R. Working to place family at the center of life: Dual-earner and single-parent strategies. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1999;562:16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann J. The widening gap: Why America’s working families are in jeopardy and what can be done about it. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton JM, Desrochers S, Devall EL. Comparison of role demands, relationships, and child functioning in single-mother, single-father, and intact families. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage. 2001;35:29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR. The second shift. New York: Avon; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Hao L, Parish WL. Race, kin networks, and assistance to mother-headed families. Social Forces. 1990;68:797–812. [Google Scholar]

- Hook J, Chalasani S. Gendered expectations? Reconsidering single fathers’ child-care time. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:978–990. [Google Scholar]

- Kendig SM, Bianchi SM. Single, cohabiting, and married mothers’ time with children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1228–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JA, Pittinsky TL. Working fathers: New strategies for balancing work and family. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McManus K, Korabik K, Rosin HM, Kelloway EK. Employed mothers and the work-family interface: Does marital status matter? Human Relations. 2002;55:1295–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Mennino SF, Rubin BA, Brayfield A. Home-to-job and job-to-home spillover: The impact of company policies and workplace culture. The Sociological Quarterly. 2005;46:107–135. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Yu Y. Effective work/life strategies: Working couples, work conditions, gender, and life quality. Social Problems. 2000;47:291–326. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MK. Single mothers “do” family. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:781–795. [Google Scholar]

- Risman BJ. Gender vertigo: American families in transition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Risman BJ, Park K. Just the two of us: Parent-child relationships in single-parent homes. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:1049–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Reskin BF. Education, control at work, and job satisfaction. Social Science Research. 1992;21:134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, McBrier DB, Van Gundy K. Home-to-work conflict, work qualities, and emotional distress. Sociological Forum. 2003;18:137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Milkie MA, Glavin P. When work interferes with life: The social distribution of work-nonwork interference and the influence of work-related demands and resources. American Sociological Review. 2009;74:966–988. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer JA. Families formed outside of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:1247–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens DP, Minnotte K, Mannon SE, Kiger G. Examining the “Neglected side of the work-family interface”: Antecedents of positive and negative family-to-work spillover. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28:242–262. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM. Remarriage and stepfamilies: Strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. On merging identity theory and stress research. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1991;54:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P. Toward a conceptualization of perceived work-family fit and balance: A demands and resources approach. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005a;67:822–836. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P. Work demands and work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: Direct and indirect relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 2005b;26:707–726. [Google Scholar]