Abstract

Intracellular-acting peptide drugs are effective for inhibiting cytoplasmic protein targets, yet face challenges with penetrating the cancer cell membrane. We have developed a lipid nanoparticle formulation that utilizes a pH-sensitive calcium carbonate complexation mechanism to enable the targeted delivery of the intracellular-acting therapeutic peptide EEEEpYFELV (EV) into lung cancer cells. Lipid-calcium-carbonate (LCC) nanoparticles were conjugated with anisamide, a targeting ligand for the sigma receptor which is expressed on lung cancer cells. LCC EV nanoparticle treatment provoked severe apoptotic effects in H460 non-small cell lung cancer cells in vitro. LCC NPs also mediated the specific delivery of Alexa- 488-EV peptide to tumor tissue in vivo, provoking a high tumor growth retardation effect with minimal uptake by external organs and no toxic effects.

Keywords: therapeutic peptide, apoptosis, nanoparticle, calcium carbonate

1. Introduction

Rapid biotechnological growth has made it possible to design therapeutic macromolecules against specific molecular targets [1, 2, 3]. However, the cellular internalization of hydrophilic therapeutics is limited by the hydrophobic interior environment of the phospholipid cellular membrane. Appropriate delivery vectors are necessary to successfully deliver hydrophilic therapeutics to the cell interior.

Intracellular therapeutic peptide delivery is a particularly appropriate strategy for treating cancer; a disease where aberrant cellular proliferation and evasion of apoptotic signaling is mediated by the over-expression of certain characteristic protein factors [4, 5]. Although most peptide anti-cancer drugs act on the extracellular surface of cancer cells, several peptide therapeutics have been developed for intracellular targeting that make use of a cell penetrating peptide (CPP) vector such as TAT, Antennapedia or Polyarginine [6, 7, 8, 9]. These CPP-protein therapeutic conjugates, however, are difficult to manufacture efficiently, encounter challenges in drug-carrier separation, demonstrate limited targeting selectivity, and can cause systemic toxicity [10, 11, 12].

A successful delivery system for transport of intracellular-acting cancer peptide drugs should provoke a long peptide circulation time, maintain the biological activity and stability of the peptide, target the peptide to the tumor site, mediate the uptake of the peptide into the target cancer cells, and successfully release the peptide drug to the cell cytoplasm [13].

Given this criteria, nanoparticles serve as particularly good vector mechanisms for cancer therapeutic transport because their advantageous size allows them to be sequestered in tumor cells due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Small (<100 nm) particles can successfully penetrate into the characteristic leaky vasculature of tumors where they are retained in dense internal connective tissue [14, 15, 16, 17]. PEGylated NPs, in particular, have also shown success at evading parts of the reticuloendothelial system (RES), concentrating NP uptake in the tumor tissue [18, 19].

We have previously delivered siRNA and an anionic therapeutic peptide into the cytoplasm of H460 lung cancer cells by encapsulating the respective drugs into a membrane/core lipid nanoparticle (NP) [5, 18]. Although this particle successfully delivered the encapsulated therapeutic, NP release of the peptide drug within the cytoplasm did not significantly occur. We postulate that the poor drug release was a result of increased retention of the dissociated peptide or protein-encapsulating NPs in the cellular endosome [20]. Recently, we have developed a lipid-apolipoprotein NP platform to successfully deliver a cytochrome c therapeutic peptide conjugated with a membrane-permeable-sequence (MPS) to the cytoplasm of lung cancer cells [21]. Delivered cytochrome c provoked massive cell apoptosis in vitro and resulted in marked tumor growth retardation in vivo, demonstrating proof-of-concept for the potential of nanoparticles to act as potent peptide drug carriers.

It has been reported that calcium phosphate (CaP) and calcium carbonate (CC) can be used to form liposomal NP complexes and facilitate drug delivery [19, 21, 22]. Unlike some polymeric NP platforms, liposomal CC (LCC) particles cause a strong proton sponge effect in the low endosomal pH, resulting in endosomal lysis and rapid dissociation of the NPs into the cell cytoplasm. LCC NPs can also be conjugated with targeting ligands, such as anisamide; a molecule specific to the sigma receptor over-expressed in lung cancer cells.

EEEEpYFELV (EV) is a nonapeptide mimicking the Y845 site of EGFR, a receptor tyrosine kinase which is responsible for STAT5b phosphorylation. The silencing of this characteristic EGFR pathway should lead to diminished EGFR-initiated cell proliferation and increased lung cancer cell apoptosis [5]. In this paper, we will detail the successful encapsulation of the EV peptide in pH-sensitive liposomal calcium carbonate NPs conjugated with an anisamide targeting ligand. We will demonstrate that our LCC NP mediates the successful delivery and release of the EV peptide inside the cytoplasm of H460 non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. We will also show the tumor targeting and therapeutic effect of the LCC NP in an H460 xenograft mouse model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane chloride salt (DOTAP), cholesterol, and 1,2-distearoryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethyleneglycol-2000)] ammonium salt (DSPE-PEG) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). DSPE-PEG-anisamide (AA) and DOPE-glutaric acid were synthesized in our lab (Supplemental Fig. 1). Therapeutic phosphorylated EV peptide (EEEEpYFELV) and control EE scrambled peptide (EpYELFEEVE) were synthesized commercially (Peptide 2.0 Corp. VA). Other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) without further purification.

2.2. Preparation of the LCC-PEG-AA NP

A schematic illustration of the LCC nanoparticle preparation incorporating the EV peptide is shown in Figure 1a. The anionic lipid-coated CC core was prepared with a water-in-oil emulsion method. Briefly, 18 μL of 3% sodium carbonate buffer (pH 8.3) was mixed with the same volume of peptide (2 mg/mL) and was dispersed in 1 mL of a cyclohexane to form a well dispersed water-in-oil emulsion. The calcium solution was prepared by adding 20 μL of a calcium chloride solution (250 mM) to 1 mL of a cyclohexane oil phase. A 25 μL volume of a 25 mg/mL 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3- phosphoethanolamine-N-(glutaryl) (DOPE-glu) solution dissolved in chloroform was added to the calcium phase. After mixing the above two solutions by sonication (15 sec, 3 times), the mixture was centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 1 min to remove the cyclohexane and excess surfactant. The core pellets were dispersed in 500 μL of water for liposomal formation with DOTAP/cholesterol (10 mg/mL). The LCC nanoparticles were further modified with 50 uL of DSPE-PEG-2000 (10 mg/mL) or DSPE-PEG-AA (10 mg/mL). The particle size and zeta potential of the finished LCC NPs were detected in 1 mM KCl using a Malvern ZetaSizer Nano series (Westborough, MA). To measure the loading efficiency of the EV peptide, free EV peptide labeled with Alexa-488 was measured after elimination of unreacted free Alexa-488 and unconjugated EV peptide using a dialysis membrane (MW: 2000). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the LCC NPs were acquired with the use of a JEOL 100CX II TEM (JEOL, Japan). The TEM sample of LCC NPs was prepared on a 300 mesh carbon coated copper grid (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of LCC nanoparticle preparation (a) and TEM imaging of unstained LCC-PEG-AA NPs (b).

2.3. Disruption of the LCC calcium carbonate core under various pH conditions

Calcium carbonate cores were formulated with the EV therapeutic peptide to evaluate whether the calcium complex core rapidly dissociates at a low pH condition. CC cores were added to 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffers of different pH levels (5.5, 6.5 and 7.4). To observe the core disruption, the intensity per second of the nanoparticle solutions was traced using a Malvern ZetaSizer Nano series (Westborough, MA) after incubation of the samples in the respective pH buffers for 30 min. Decreases in particle intensity represented disruption of the inner LCC core. The experiment was duplicated and the data was expressed as a mean average intensity with the standard deviation also represented as error bars.

2.4. Release profile of fluorescently-labeled EV peptide from LCC-PEG-AA NPs under different pH conditions

LCC-PEG-AA NPs encapsulating Alexa-488-EV were incubated for 5 min in 500 μL of phosphate buffers adjusted to different pH levels. Samples were then spun down and the supernatant containing released EV peptide was separated from the NP material pellet and was loaded into a tricine/SDS PAGE gel [5]. After running the samples, the gel was visualized using a Kodak imaging system “FX Pro” for examination of the fluorescence peptide bands released from LCC.

2.5. Cellular uptake of EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs

NCI-H460 human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 100 μg/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). H460 cells were previously shown to be sigma-1 receptor positive and to have a moderate level of EGFR protein expression [23, 24]. H460 cells (1 × 105 per well) were seeded in 24-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) under covered glass for 12 h before treatment. Cells were then treated with a 100 nM final concentration of different LCC formulations at 37 °C for 3 h. After two PBS wash cycles, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma). Cells were imaged with use of a Leica SP2 confocal microscope (Leica, Bannockburn, IL).

2.6. MTT cellular proliferation assay for determination of H460 cell viability after EV in LCC-PEG-AA NP treatment

H460 cells (5 × 105) were incubated with 1 μM of various LCC nanoparticle formulations for 12, 24 or 36 h. At each time interval, cell viability was measured using an MTT assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with lysed cells as a negative control and untreated cells serving as a positive control.

2.7. Flow cytometry for detection of H460 cell apoptosis caused by EV in LCC-PEG-AA NP treatment

Discrimination of apoptotic cellular subpopulations was evaluated using flow cytometry after treatment of H460 cells (5 × 105) with 2 μM of various LCC nanoparticle formulations for 36 hours. After treatment, cells were washed with a binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2). Collected samples were then suspended in 50 μL of calcium binding buffer and 3 μL of Annexin V-FITC (0.5 mg/mL) was added to each sample. After washing with PBS buffer, cells were suspended in 500 μL of calcium binding buffer and PI (5 mg/mL) was added to the solution. Cells were immediately analyzed using a BD FACS Canto™ flow cytometer (BD biosciences, San Jose, CA).

2.8. Tissue distribution of the EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs in vivo

Female nude mice 5–6 weeks of age were purchased from NCI. All work performed on animals was in accordance with the standards of the IACUC committee. NCI-H460 cells (5 × 106 cells) were introduced by intracutaneous injection to the rear side on the back of nude mice. When the tumor measured 0.5 to 0.8 cm in diameter, different formulations of Alexa-488 labeled-EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs were i.v. injected in the mice (400–500 μg/kg) via the tail vein. After 4 h, the mice were sacrificed and their tissues collected and imaged by the IVIS™ Imaging System (Xenogen Imaging Technologies, Alameda, CA). The total average fluorescence intensity of the tumors from each mouse group was quantified using Image J software (tumor area x fluorescence intensity).

2.9. In vivo tumor growth regression after EV in LCC-PEG-AA NP treatment

The NCI-H460 xenograft (40–50 mm2) tumor bearing mice were produced on the 6th d after intradermal injections of 5 × 106 cells in the back side of nude mouse. The mice were randomly assigned to different treatment groups (n=5~6 for each group) and were tail-vein injected every other day with various formulations of EE or EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs (0.36 mg/kg). Tumor growth was monitored every 2 days thereafter and, at the end of the experiment, all mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

2.10. In vivo toxicity of EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs in CD-1 mice

CD-1 mice were randomly divided into 4 groups with 5 mice in each group. The first group was designated as a control group that was i.v. injected with PBS only. The second group was injected with 0.36 mg/kg of free EV peptide. The other two groups were injected with 0.36 mg/kg of EV peptide or EE peptide in various LCC NP formulations, respectively. All treatments were injected in the mice every other day for 10 days. Tumor size in each mouse was measured with a caliper. Two days after the last injection of LCC formulation (Day 16 in Fig. 7), blood samples were collected from the retroorbital puncture and were analyzed immediately for serological parameters. The blood sample tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min, and were then stored at −20°C until analysis for serological parameters could be performed. The serological parameters measured included the following: alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), creatine, BUN (blood urine nitrogen), sodium and calcium levels.

Fig. 7.

Tumor growth retardation effect of EV peptide. Nude mice bearing human H460 tumor were i.v. injected (0.36 mg/kg) every other day with either PBS, free EV peptide, or EE or EV peptide formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs. *: P < 0.05, Mean ± SEM (n=4–5).

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data is expressed as mean ± SEM and was analyzed using Microsoft Excel (office 2007) and Sigma plot Ver. 10 software. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way Analysis of Variation (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett-test for differences among treatment groups (Keyplot ver 2.0 software). Values of P<0.05 were considered significant.

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Characterization of LCC nanoparticle

The calcium carbonate LCC core demonstrated a slightly negative zeta potential (−5 to −10 mV). Size and zeta potential analysis of the complete LCC NPs determined that the NPs exhibit a 50–70 nm diameter and a positive +15 mV zeta potential. The zeta potential difference between the final particle and the LCC core can be attributed to the additional positive charge of the DOTAP/cholesterol external LCC core coating. TEM analysis confirmed that LCC NPs are spherical in shape with a dark calcium carbonate core and an average diameter of 60–70 nm (Fig. 1b). The LCC-PEG-AA NP encapsulation efficiency of Alexa-488 fluorescently-labeled EV peptide was determined to be 65–70% by incubating the particles in different pH buffers and analyzing the released EV quantity on an SDS-PAGE gel. The quantity of peptide, calcium and surfactant in the LCC nanoparticle was optimized at a final respective proportion of 1:180:25 to maximize the simultaneous liposomal encapsulation of both the EV peptide and the calcium carbonate core.

3.2. Disruption of LCC core and release of Alexa-488 fluorescently-labeled EV peptide in different pH environments

LCC core, prepared without the addition of the DOTAP/cholesterol external liposomal layer, was exposed to different pH environments to evaluate the release of fluorescently-labeled EV peptide in an acidic environment representative of the cellular endosome. As shown in figure 2a, LCC cores rapidly dissociate at a low 5.5 pH within five minutes and moderately dissociate at a pH 6.5 condition. It was also determined that the LCC core is stable with negligible breakdown at a pH of 7.4. We verified whether the observed LCC dissociation translates into increased release of the encapsulated Alexa-488 fluorescently-labeled EV peptide. At a pH of 7.4, negligible EV release was observed from sample solutions visualized on a SDS page gel (Fig. 2b). Overall, a pH-dependent trend was observed; greater EV peptide band saturation occurred in LCC NP samples that were incubated in a lower pH environment. The EV peptide band released from LCC NPs at a pH of 5.5 was 3 times stronger than the fluorescent band obtained from LCC NPs incubated at a pH of 6.5.

Fig. 2.

Stability of the pH sensitive calcium carbonate core studied at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 45 min exposure to different pH conditions (pH 5.5, 6.5 or 7.4). The disruption of the formation of calcium cores was measured using dynamic light scattering (average mean value of detected particle intensity per second (%)) (a). Release profiles of Alexa-488-EV peptide formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs under different pH conditions were observed by SDS-PAGE analysis followed by imaging with a KODAK imaging system (b).

3.3. Uptake of LCC NPs encapsulating Alexa-488 fluorescently-labeled EV peptide by H460 cells

H460 cells incubated with LCC-PEG-AA NPs encapsulating Alexa-488 fluorescently-labeled EV peptide demonstrated significant NP uptake and EV localization in the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 3b) when compared to H460 cells treated with free Alexa-488 labeled EV peptide (Fig 3a).

Fig. 3.

EV Peptide uptake by H460 cells. Uptake of Alexa-488-EV peptide formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs was observed by confocal microscopy, 40X (b). Free Alexa-488-EV peptide treated cells were used as the comparative control (a).

3.4. Inhibition of H460 cell proliferation induced by EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs

H460 cells treated with 1 μM of the EV peptide encapsulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs showed a significant 40% reduction in viability compared to an untreated control after 36 h of NP treatment (Fig. 4). In comparison, H460 cells treated with LCP-PEG-AA NPs formulated with the scrambled EE peptide showed a slight 10–12% reduction in cell viability compared to an untreated control. Previously, we have documented that this decrease could be attributed to a mild cytotoxic effect provoked by intracellular delivery of EE [5].

Fig. 4.

MTT assay of H460 cell viability after treatment with 1 μM of EV or EE formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs for different incubation time intervals (12, 24 and 36 h). Viabilities were calculated as compared to an untreated control at each time point. P < 0.05 *.

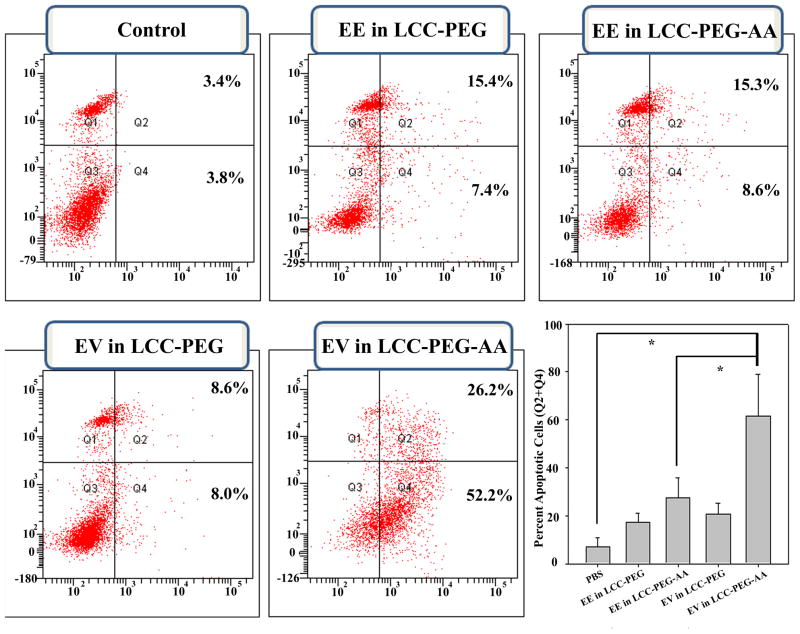

3.5. Apoptotic induction and cell cycle arrest provoked by EV-encapsulating LCC NPs

H460 cells were treated with 2 μM of either the EV or EE peptide in different LCC formulations for 36 h, then the cytotoxic effect of each treatment was evaluated by Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry (Fig. 5). As shown by the combined Q4 and Q2 quadrants of each distribution chart, indicative of early and late apoptotic induction, respectively, H460 cells underwent massive apoptosis (70–80%) after treatment with LCC-PEG-AA NPs encapsulating the EV peptide. In comparison, only about 15% of H460 cells treated with the scrambled EE peptide delivered with either LCC-PEG or LCC-PEG-AA showed apoptotic induction. LCC NPs formulated with EV in the absence of PEG-AA showed a marked decrease in cell targeting, indicating that PEG-AA improves the therapeutic efficacy of the LCC NP in vitro.

Fig. 5.

Cellular apoptosis of H460 lung cancer cells evaluated by flow cytometry. Cells were treated for 36 h with 2 μM of EE or EV peptide formulated in either LCC-PEG NPs or LCC-PEG-AA NPs. A control sample was treated with PBS buffer (pH 7.4). Apoptotic cells (early and late apoptosis) were quantified (right lower panel). P < 0.05 *.

3.6. In vivo tissue distribution of the EV formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs

Nude mice bearing an H460 tumor xenograft were i.v. injected with various formulations of LCC NPs encapsulating a fluorescently-labeled, Alexa-488 EV peptide to evaluate the NP distribution in vivo. Mice treated with LCC NPs including DSPE-PEG showed little fluorescence in the liver and a comparatively greater intensity in the tumor (Fig. 6). NPs produced with DSPE-PEG-AA provoked an even greater tumor fluorescence, with the majority of experimental mice showing no significant fluorescence elsewhere in the body. This data suggests that the tumor was the major site of peptide uptake. This observation is supported by an estimate of the total fluorescence intensity of the tumors from each treatment group (Fig. 6b). Mice treated with EV in LCC-PEG-AA showed a dramatically higher amount of Alexa-488 EV peptide retention compared to mice treated with free EV peptide.

Fig. 6.

Tissue distribution of EV peptide. Major organs were taken from H460 tumor bearing mice 4 h after i.v. injection with Alexa-488-EV peptide formulated in LCC-PEG or LCC-PEG-AA NPs (a). Imaging was performed with use of an IVIS 100 imaging system. Quantification of the total average fluorescence intensity (tumor area x fluorescence intensity) of the tumors from each mouse group was estimated using Image J software (b).

3.7. In vivo tumor growth retardation effect after treatment of H460 xenograft mice with EV formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs

We examined whether the EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs was able to provoke anti-tumor effects after systematic i.v. injection. Figure 7 clearly illustrates a dramatically significant reduction in tumor growth after mouse treatment with EV-encapsulating, LCC-PEG-AA NPs. Xenograft mice treated with free EV peptide or LCC-PEG-AA NPs encapsulating EE peptide showed no significant tumor growth reduction compared to tumor growth observed in mice treated with PBS.

3.8. Serological toxicity evaluation of EV formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs

Biochemical parameters, including AST, ALT and ALP, were measured at the completion of NP treatment to evaluate the toxic effect of the EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs on the liver (Table 1). All measured serological values of the EV in LCC-PEG-AA treated mice were similar to those of the control group. This result demonstrates that there are no significant, prolonged systematic toxic effects induced by EV formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs.

Table 1.

Serological parameters of blood samples taken from CD-1 mice treated with EV formulated in LCC-PEG-AA NPs

| PBS | Peptide | Calcium sol. | LCC-PEG-AA EE |

LCC-PEG-AA EV |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUN (mg/dl) | 21.6 ± 5.2 | 19.0 ± 1.4 | 21.3 ± 3.3 | 22.5 ± 3.4 | 20.5 ± 1.3 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 114.4 ± 0.5 | 117.0 ± 1.4 | 119.0 ± 1.8 | 120.3 ± 1.7 | 119.3 ± 0.9 |

| AST (u/L) | 255.8 ± 128.1 | 165.0 ± 42.4 | 201.8 ± 42.1 | 252.5 ± 111.1 | 198.0 ± 52.7 |

| ALP (u/L) | 86.6 ± 23.1 | 77.5 ±0.7 | 69.3 ± 6.2 | 72.0 ± 27.5 | 61.3 ± 4.3 |

| ALKP (u/L) | 167.8 ± 19.9 | 124.5 ± 9.2 | 139.8 ± 19.5 | 147.3 ± 22.6 | 118.0 ± 10.5 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.3 ± 0.9 | 8.3 ± 0.3 | 8.5 ± 0.1 | 9.8 ± 0.4 | 9.7 ± 0.1 |

4.0. Discussion

Delivery of an intracellular-acting therapeutic by route of receptor mediated endocytosis is difficult because drug carriers often cannot both maintain integrity when trapped inside an endosome and mediate endosomal release of the drug cargo into the cell cytoplasm. It has been shown that cationic drug-carrying polymers enriched with secondary and tertiary amino groups can induce endosomal accumulation of chloride ions, subsequently leading to the rupture of the endosome membrane by increased osmotic pressure, a phenomenon known as the “proton sponge effect” [25]. However, cationic polymers also provoke highly toxic effects, limiting their potential as therapeutic vectors in vivo.

In a previous study, we developed an LPH nanoparticle using cationic protamine to facilitate the delivery of EV peptide into the cytoplasm of H460 cells in vivo [5]. Although the LPH NP was able to successfully penetrate into the cell, minimal EV endosomal release was observed. We have developed the LCC NP, including a calcium complex core, as a completely different delivery system to facilitate improved peptide endosomal release and increased therapeutic efficacy.

Our NP platform operates using a phenomenon similar to the proton sponge effect used to free ingested NPs from the endosome. Compared to the LPH EV NP, the LCC EV NP includes a markedly different type of composition, including an inner calcium core and an overall more compact size. As shown in figure 1a, calcium carbonate can mediate the formation of calcium complexes which are able to tightly bind to negatively charged therapeutics, such as the EV peptide, due to the high affinity of the calcium ions for the carbonyl groups. The LCC NP encapsulates these calcium-drug complexes with an anionic lipid DOPE-glu acting as a surfactant. Figure 1b depicts the homogenous spherical shape and size of the produced LCC NPs which are manufactured with a dense internal calcium core and a faint outer lipid coating.

We postulate that upon receptor-mediated ingestion of our LCC NPs, the calcium complex should moderate an increase of calcium and bicarbonate/carbonate ions in the acidic endosomal environment, causing osmotic swelling. This effect would serve as a novel mechanism facilitating NP escape from the endosome and subsequent drug release to the cytoplasm. To test this concept, we exposed the EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs to different acidic environments and measured the dissociation of the internal calcium complex encapsulating fluorescently-labeled EV peptide. The LCC calcium core complex was easily dissociated in a low pH buffer, releasing EV peptide in a pH-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). At a 5.8 acidic pH representative of the endosomal environment, fluorescently-labeled EV peptide was released from fully formed LCC-PEG-AA NPs in significantly greater amounts than observed at more basic pH levels. Importantly, at a pH of 7.4, a pH condition representative of the bloodstream, negligible core dissociation was detected.

This calcium complex core dissociation and release process may have been aided by the DOTAP/cholesterol lipid coat surrounding the DOPE-glu-calcium complex. Before the addition of DOTAP/cholesterol, the calcium carbonate core should be coated with DOPE-glu because the glutamic acid headgroup of DOPE-glu readily interacts with calcium ions. During the formation of the LCC NP, DOTAP/cholesterol should further coat the core to form the outer leaflet of the coating lipid bilayer, resulting in stable NPs in an aqueous solution. When the LCC NPs disassemble in the endosome, the cationic lipid DOTAP may form ion-pairs with the anionic endosomal lipids, leading to further destabilization of the endosome and the release of peptide cargo into the cytoplasm. The conversion of the LCC’s carbonate to bicarbonate and, finally, to carbon dioxide, may also have provoked additional stress leading to a rupture in the cellular endosome.

The ability of the LCC NP to enter cancer cells and localize in the cell cytoplasm was also demonstrated. As shown by figure 3b, treatment of H460 non-small cell lung carcinoma cells with LCC-PEG-AA NPs resulted in cell uptake and detection of the encapsulated fluorescently-labeled EV peptide in the cell cytoplasm. Successful EV peptide delivery and release into the cytoplasm should induce a therapeutic effect, as EV peptide has been shown to inhibit the phosphorylation of STAT5b [5]. Indeed, figure 4 demonstrates a 40% decrease in H460 cell viability after 36 h of treatment with 1 μM of EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs. H460 cells treated with LCC-PEG-AA showed not only diminished viability, but also a significant increase in apoptosis compared with control formulations (Fig. 5). This indicates that LCC-PEG-AA NPs can facilitate the transport of EV peptide to the cytoplasm where it can interact with its molecular target: the kinase domain of EGFR. It should be noted that LCC-PEG-AA treatment provoked a significant decrease in cell viability at a final dosed EV concentration of 1 μM (Fig. 4). Previously, it has been shown that the IC50 of free EV peptide for inhibiting EGFR activity is about 2 μM [5]. Our result, therefore, implies that LCC-PEG-AA NPS are highly permeable through the cell membrane, provoking more efficient cell uptake and eventual endosomal release of EV when compared to cell uptake of free EV peptide.

In an H460 xenograft mouse model, the LCC-PEG-AA NP demonstrated significant tumor targeting ability, specifically delivering fluorescently-labeled EV peptide to the tumor (Fig. 6a). This tumor targeting effect was partly the result of DSPE-PEG-AA addition to the LCC NP. Sigma receptor is a marker for epithelial cells and is over-expressed in many human lung cancer cells [24, 26, 27, 28]. DSPE-PEG-AA, which contains an anisamide targeting moiety against the sigma receptor, facilitates the specific binding of NP to tumor cells [24]. Indeed, mice treated with NPs formulated without the anisamide targeting ligand showed less EV peptide tumor uptake than mice treated with EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs (Fig 6b).

The therapeutic advantage of the anisamide targeting ligand was more pronounced in an H460 xenograft tumor growth inhibition analysis (Fig. 7). H460 xenograft mice treated with PBS, free EV peptide, or EE in LCC-PEG-AA NPs all showed no significant tumor growth inhibition. In comparison, mice treated with EV in LCC-PEG-AA NPs witnessed a significant decrease in tumor growth over two weeks. Importantly, serological proteins and other factors collected from mice treated with NP formulations were consistently normal, indicating low in vivo toxicity (Table 1). The normal levels of biochemical parameters assessing liver integrity, such as AST, ALP and ALKP, especially indicate the safety of the LCC-PEG-AA NP system.

Overall, our current LCC formulation compares favorably with the previous LPH (Liposome-Protamine-Heparin) formulation which was also used to deliver the EV peptide [5]. The major compositional difference between the two involves the addition of a calcium core for drug encapsulation in the LCC NP. The LPH protamine-heparin complex can readily encapsulate a negatively charged peptide such as EV, yet the loaded NP is not highly sensitive to environmental conditions affecting cargo release. The LCC’s calcium-carbonate core, however, is acid sensitive (Fig. 2) with the ability to moderate a more controlled cargo release at the pH condition commonly found in endosomes. We believe that this acid sensitivity facilitates an increased endosomal release of the EV peptide from the LCC NPs inside tumor cells compared to the intracellular release of EV from LPH NPs.

In addition, the pH-sensitivity may delay the release of EV peptide from the LCC NPs at higher pHs in the bloodstream, as shown by figure 2, concentrating EV peptide release to the intracellular compartments of targeted cancer cells. Using the same in vivo model as observed in the LPH study, figure 6 clearly shows that EV peptide delivered by LCC-PEG-AA NPs is concentrated mainly within tumor cells, with some treated mice showing no EV retention in the liver.

In a previous paper, we show that the EV therapeutic peptide has an IC50 of about 2 μM in inhibiting EGFR kinase, and that the LPH NPs were able to deliver sufficient EV to reach a similar intracellular concentration [5]. Although one expects that the LCC NP will deliver more EV intracellularly than the LPH NP, similar efficacy in tumor growth retardation was observed for both formulations ([5] and Fig. 7 in the current manuscript). One possible reason for the apparent discrepancy is that the LCC NP has already delivered EV to a concentration approximately equal to the IC50 of the drug. Further increase of intracellular EV concentration resulting from LCC delivery would not cause any significant enhancement in tumor growth inhibition.

The most important improvement of the LCC NP involves its potential ability to encapsulate a variety of drugs based on a reverse-emulsion preparation of the internal core. In comparison, the LPH NP relies on charge-charge interaction to capture its cargo, severely limiting the LPH loading capacity of non-highly charged drugs. Overall, compared to the LPH NP, the LCC NP demonstrates a more compact size, an increased pH-controlled peptide-carrier separation (translating to improved intracellular endosomal release), a highly successful tumor growth retardation arrest, a favorable biodistribution, and a more inclusive outlook for delivering non-highly charged therapeutic peptides. The LCC formulation, therefore, improves upon all of the beneficial therapeutic and targeting properties of the LPH system with additional platform flexibility and an expanded therapeutic scope.

Supplementary Material

Structure and synthesis of DOPE-glu. 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3- phosphoethanolamine-N-(glutaryl) was synthesized by reacting 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethenolamine (DOPE) with glutaric anhydride.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants CA129835 and CA149363.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kumar S, Blake SM, Emery JG. Intracellular signaling pathways as a target for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2001;1:307–313. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(01)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matter A. Tumor angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Drug Discov Today. 2001;6:1005–1024. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(01)01939-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lark MW, Morrison KE. Musculoskeletal diseases: novel targets for therapeutic intervention. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:287–290. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bidwell GL, III, Raucher D. Therapeutic peptides for cancer therapy. Part I peptide inhibitors of signal transduction cascades. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6(10):1033–1047. doi: 10.1517/17425240903143745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SK, Huang L. Nanoparticle delivery of a peptide targeting EGFR signaling. J Control Release. 2012;157(2):279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Andaloussi S, Holm T, Langel Ü. Cell-penetrating peptides: mechanisms and applications. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2005;11:3597–3611. doi: 10.2174/138161205774580796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Futaki S, Suzuki T, Ohashi W, Yagami T, Tanaka S, Ueda K, Sugiura Y. Arginine-rich peptides: An abundant source of membrane-permeable peptides having potential as carriers for intracellular protein delivery. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5836–5840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng YL, Liu JJ, Hong RL. Translocation of Liposomes into Cancer Cells by Cell-Penetrating Peptides Penetratin and Tat: A Kinetic and Efficacy Study. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:864–872. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bitler BG, Schroeder JA. Anti-cancer therapies that utilize cell penetrating peptides. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2010;5(2):99–108. doi: 10.2174/157489210790936252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardozo AK, Buchillier V, Mathieu M, Chen J, Ortis F, Ladrière L, Allaman-Pillet N, Poirot O, Kellenberger S, Beckmann JS, Eizirik DL, Bonny C, Maurer F. Cell-permeable peptides induce dose- and length-dependent cytotoxic effects. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2007;1769(9):2222–2234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foerg C, Merkle HP. On the biomedical promise of cell penetrating peptides: limits versus prospects. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97(1):144–62. doi: 10.1002/jps.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Said Hassane F, Saleh AF, Abes R, Gait MJ, Lebleu B. Cell penetrating peptides: overview and applications to the delivery of oligonucleotides. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(5):715–726. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0186-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trabulo S, Cardoso AL, Mano M, Pedroso De Lima MC. Cell penetrating peptides-Mechanisms of cellular uptake and Generation of delivery system. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3(4):961–993. doi: 10.3390/ph3040961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hobbs K, Monsky W, Yuan F, Roberts W, Griffith L, Torchilin VP, Jain R. Regulation of transport pathways in tumor vessels: Role of tumor type and microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4607–4612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, Leunig M, Berk DA, Torchilin VP, Jain RK. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3752–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho K, Wang X, Nie S, Chen(Georgia) Z, Shin DM. Therapeutic Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery in Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1310. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Praetorius NP, Mandal TK. Engineered nanoparticles in cancer therapy. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2007;1(1):37–51. doi: 10.2174/187221107779814104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li SD, Huang L. Nanoparticles Evading The Reticuloendothelial System: Role of The Supported Bilayer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:10:2259–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo S, Huang L. Nanoparticles Escaping RES and Endosome: Challenges for siRNA Delivery for Cancer Therapy. J Nanomater. 2011;2011:12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SK, Foote M, Huang L. The targeted intracellular delivery of cytochrome c protein to tumors using lipid-apolipoprotein nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33:15. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Chen YC, Tseng YC, Huang L. Biodegradable Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticle with Lipid Coating for Systemic siRNA Delivery. J Control Release. 2010;142(3):416–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Yang Y, Huang L. Calcium phosphate nanoparticles with an asymmetric lipid bilayer coating for siRNA delivery to the tumor. J Control Release. 2012;158(1):108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steiner P, Joynes C, Bassi R, Wang S, Tonra JR, Hadari YR, Hicklin DJ. Tumor Growth Inhibition with Cetuximab and Chemotherapy in Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Xenografts Expressing Wild-type and Mutated Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1540. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S, Chen YC, Hackett MJ, Huang L. Tumor-targeted Delivery of siRNA by Self-assembled Nanoparticles. Mol Ther. 2008;16(1):163–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boussif O, Lezoualc’h F, Zanta MA, Mergny MD, Scherman D, Demeneix B, Behr JP. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(16):7297–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aydar E, Palmer CP, Djamgoz BA. Sigma receptors and cancer: possible involvements of ion channels. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5029–5035. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.John CS, Varma VM, McAfee JG, Moody TW. Sigma receptors are expressed in human non-small cell lung carcinoma. Life Sci. 1995;56:2385–2392. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00232-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vilner BJ, John CS, Bowen WD. Sigma-1 and sigma-2 receptors are expressed in a wide variety of human and rodent tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1995;55:408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Structure and synthesis of DOPE-glu. 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3- phosphoethanolamine-N-(glutaryl) was synthesized by reacting 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethenolamine (DOPE) with glutaric anhydride.