Abstract

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium sexually transmitted to more than 90 million individuals each year. As this level of infectivity implies, C. trachomatis is a successful human parasite; a success facilitated by its ability to asymptomatically infect women. Host defense against C. trachomatis in the female genital tract is not well defined, but current dogma suggests infection is controlled largely by TH1 immunity. Conversely, it is well established that TH2 immunity controls allergens, helminths, and other extracellular pathogens that cause repetitive or persistent T cell stimulation but do not induce the exuberant inflammation that drives TH1 and TH17 immunity. As C. trachomatis persists in female genital tract epithelial cells but does not elicit overt tissue inflammation, we now posit that defense is maintained by TH2 immune responses that control bacterial growth but minimize immunopathological damage to vital reproductive tract anatomy. Evaluation of this hypothesis may uncover novel mechanisms by which TH2 immunity can control growth of C. trachomatis and other intracellular pathogens, while confirmation that TH2 immunity was selected by evolution to control C. trachomatis infection in the female genital tract will transform current research, now focused on developing vaccines that elicit strong, and therefore potentially tissue destructive, Chlamydia-specific TH1 immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Host defense

Protection against microbial pathogens is orchestrated by a coordinated system in which innate immune responses supply the first lines of defense and drive the formation of more specialized adaptive immune responses. Depending on the infection, dendritic cells (DC) and other innate immune cells express distinct sets of costimulatory molecules and cytokines that trigger naïve CD4+ T cells to form various types of effector cells, three of which are termed TH1, TH2, and TH17 [1]. Specifically, many intracellular bacteria and viruses induce DC and natural killer (NK) cells to produce interleukin (IL)-12 and interferon (IFN)-γ, which drives TH1 differentiation; helminths and other extracellular pathogens cause innate immune cells to secrete IL-4, which promotes TH2 differentiation; while other bacteria and fungi stimulate DC to produce IL-1, IL-6, and transforming growth factor-β, which induces TH17 differentiation [2-5]. Such specialized adaptive immune responses allow animal hosts to optimize their defenses against a diverse array of naturally encountered pathogens.

Naïve CD4+ T cells stimulated to form TH1 cells then secrete high levels of IFN-γ, activating macrophages (called classical macrophage activation) to phagocytose and eliminate the microbes that triggered TH1 development [6]. TH1 CD4+ T cells also secrete tumor necrosis factor and proinflammatory chemokines that recruit additional leukocytes to active infection sites [7]. However, when TH1 immunity cannot adequately control infection, host defense may be polarized toward TH 2 immune responses that curb TH1-mediated inflammation and inhibit collateral tissue damage [8]. For example, helminths and other extracellular pathogens refractory to phagocytic killing stimulate TH2 CD4+ T cells to secrete IL-4, IL-11, and IL-13, responses that: inhibit TH1 and TH17 cell development, decrease inflammatory cell recruitment, and activate macrophages to promote tissue remodeling and wound healing (called alternative macrophage activation) [9, 10].

Endocervical Chlamydia trachomatis infection

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium, and exclusively a pathogen of humans. With at least 90 million new cases globally each year, this microorganism is the most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection [11]. The highest prevalences of genital tract Chlamydia infection are found among adolescents and young adults, and migration of the organism from the lower to upper female genital tract can cause Fallopian tube damage, and increase the risk for ectopic pregnancy and tubal factor infertility [12]. Persistent infection is another risk factor for phenotypic expression of chlamydial disease [13], and is facilitated by the ability of C. trachomatis to asymptomatically infect women [14]. In fact, without administration of an appropriate antimicrobial, this organism can persist subclinically in genital tract epithelium for years after initial infection [15]. Interestingly, chlamydial infection control programs that augment detection and treatment of asymptomatically individuals concomitantly increase populational susceptibility to infection, suggesting that an earlier eradication of the organism interrupts development of slow-to-form Chlamydia -specific protective immunity [16-18]. Moreover, even though C. trachomatis is a Gram-negative bacterium, its cell wall contains lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that is at least 100-fold less potent than LPS contained in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a Gram-negative bacterium that elicits more robust genital tract inflammation [19]. Collectively, these clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory findings indicate that C. trachomatis is a weakly antigenic parasite that elicits mild inflammatory responses and asymptomatically persists in the female genital tract; thus optimizing its chances for transmission and its survival fitness.

HYPOTHESIS

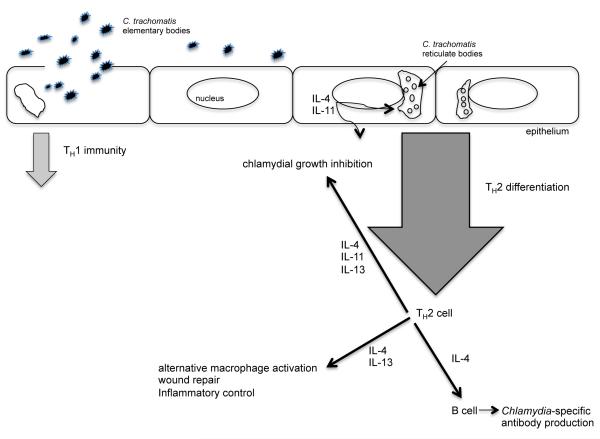

As TH2 differentiation is promoted by weakly antigenic pathogens and pathogens refractory to eradication by TH1 and TH17 immunity, we posit that defense against C. trachomatis in the female genital tract is ultimately regulated by TH2 immune responses that control chlamydial replication and suppress immunopathological damage to vital reproductive tract structures (Figure).

Cartoon depiction of host defense against Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the female genital tract.

Although C. trachomatis acquisition may initially induce TH1 immune responses, we hypothesize that persistent infection elicits responses that suppress TH1 immunity and polarize host defense toward TH2 immunity. In response to persistent infection, we further hypothesize that TH2 CD4+ T cells secrete cytokines, which stimulate Chlamydia-specific antibody production, inhibit chlamydial growth, and activate macrophages that dampen inflammation and promote tissue repair.

TESTING THE HYPOTHESIS

To begin exploration of this hypothesis, we completed immunohistochemical analyses, with antibodies specific for macrophages, NK cells, T cells, B cells, and plasma cells, to characterize the leukocyte subpopulations in paraffin-embedded endometrial tissue from 37 uninfected women and 27 women with C. trachomatis genital tract infection. Among Chlamydia -infected study participants, 17 were diagnosed with endocervical infection alone, and 10 were diagnosed with both endocervical and endometrial infection [20]. Compared to uninfected women, we found that endocervical C. trachomatis infection was associated with significant increases in endometrial T cells, B cells, and plasma cells. As the numbers of endometrial stromal cells positive for CD3 (a pan T cell marker), but not CD8, were increased among these women, our results also implied that CD4+ cells were the T cell subset specifically increased by endocervical C. trachomatis infection. Ascension of C. trachomatis into the upper genital tract elicited even more substantial increase in the numbers of endometrial CD4+ T cells, B cells, and plasma cells compared to when infection was confined to the lower genital tract, although infection in these women was also asymptomatic. While these investigations confirm that cell mediated immunity, including increases in CD4+ T cell numbers, are elicited by C. trachomatis infection of the female genital tract, further work is needed to determine the CD4+ effector cell subsets specifically selected by evolution to combat Chlamydia infection.

Future studies exploring our hypothesis should define which of the transcription factors regulating T cell differentiation are preferentially expressed among CD4+ cells infiltrating the genital tract of women with C. trachomatis infection. TH1 cell differentiation, for example, is associated with expression of T-bet, a transcription factor that is considered the master regulator of the TH1 response [21]. Similarly, TH2 and TH17 immunity is driven by host responses that increase expression of the transcription factors GATA-3 and RORγt, respectively [22]. We hypothesize that acquisition of C. trachomatis is associated, at first, with TH1 differentiation, and increased T-bet expression by genital tract CD4+ T cells. However, as TH1 immunity cannot prevent C. trachomatis from establishing a persistent genital tract infection, host defense is increasing polarized toward TH2 responses that dampen tissue inflammation and inhibit collateral damage to vital reproductive tract anatomy. Thus we also hypothesize that CD4+ T cells in the genital tract of women with chronic C. trachomatis infection will preferentially express GATA-3, the master regulator of TH2 immunity. If our hypotheses are correct, it will then be important to explore if Chlamydia-infected epithelial cells, or perhaps other innate immune cells, are responsible for inducing this TH2 differentiation.

Accordingly, the effector function of Chlamydia-specific CD4+ memory T cells isolated from the blood and genital tract of women with prior or existing genital tract infection should also be examined. As we predict that initial acquisition of C. trachomatis elicits TH1 immunity, a fraction of these CD4+ memory T cells from these women are expected to produce IFN-γ in response to ex vivo stimulation with chlamydial antigen. However, as we hypothesize that host defense against C. trachomatis becomes increasingly polarized toward TH2 immunity, a significant number of Chlamydia-specific CD4+ memory cells are expected to exhibit a TH2 phenotype and produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in response to similar stimulation. We further predict that differentiation of TH2 immune responses in women with persistent C. trachomatis infection will stimulate macrophages to promote tissue remodeling and repair (as opposed to IFN-γ activated macrophages, which show increased microbicidal function) [23-25].

If the studies outlined above determine that host defense in the genital tract of Chlamydia-infected women becomes polarized toward T H2 immunity, other work would need to define if TH2 immunity also controls C. trachomatis replication in genital tract epithelial cells. Previous studies showed the IFN-γ controls growth of Chlamydia species in vitro by inducing the production of indoleamine-2, 3-dioxygenase, an enzyme that degrades tryptophan, and hinders Chlamydia spp. growth by tryptophan starvation [26]. However, there is little evidence to support that Chlamydia-specific TH1 immunity is a biologically relevant response in the genital tract of women, and that chlamydial growth is controlled in vivo by this mechanism. Among the few studies to examine this question, commercial sex workers in Kenya whose peripheral blood mononuclear cells produced IFN-γ in response to ex vivo stimulation with chlamydial antigen had increased resistance to C. trachomatis genital tract re-infection, but this study was unable to assess if these protective TH1 responses were also associated with increased genital tract inflammation and collateral tissue damage [27]. However, there is equally little data supporting greater relevance of another CD4+ T cell subset. Thus, future studies will also need to examine the possibility that TH2 immunity was selected by evolution to defend against C. trachomatis infection in women as a means to prevent prolonged or excessive inflammation from damaging reproductive tract tissue. In conjunction with such studies, however, is the need to explore the possibility that T H2 immune responses can regulate C. trachomatis replication. Although we hypothesize that TH 2 immunity will not curb Chlamydia growth as effectively as TH1-mediated tryptophan starvation, such work has the potential to uncover novel, biologically relevant mechanisms by which TH2 immunity inhibits growth of Chlamydia and other intracellular bacteria. Such possibilities are, of course, now speculative, but they are consistent with observations that indicate C. trachomatis genital tract infection of women is asymptomatic, maintained long-term at low levels of bacterial burden, and only slowly cleared in the absence of antimicrobial administration.

HYPOTHESIS IMPLICATIONS FOR CHLAMYDIAL PATHOGENESIS

If correct, our hypothesis would transform prophylactic C. trachomatis vaccine development, as much of its current focus is based on the results from murine models of infection that suggest strong Chlamydia-specific TH1 immunity will be an essential element of an effective vaccine. However, murine infection rather imprecisely models the pathogenesis of human C. trachomatis endocervical infection. In the first place, most of these mice were intravaginally infected with C. muridarum, a chlamydia species that is not a natural pathogen of the murine reproductive tract [28]. Perhaps because C. muridarum did not evolve as a murine genital tract pathogen, intravaginal infection stimulates strong innate immune responses and the differentiation of TH1 (primarily) and TH17 immunity [29]. This vigorous host response typically clears C. muridarum within 1 month of infection, unlike C. trachomatis, which is more likely to cause chronic infection in women [30]. In the process of eradicating experimental intravaginal infection, TH1 immunity against C. muridarum also causes significant damage to the upper genital tract of mice, including frequent development of hydrosalpinx (a dilated, fluid-filled Fallopian tube) [31]. This is in stark contrast to endocervical infection of women, in which C. trachomatis is only infrequently responsible for upper genital tract damage [32]. Therefore, use of the results from murine models to draw conclusions about the response of women to endocervical C. trachomatis infection has likely overestimated the biological relevance of TH1 immunity.

Although murine infection inadequately models endocervical C. trachomatis infection of women, it has been useful to re-enforce the concepts that animal defense mechanisms co-evolved with a defined set of pathogens and hosts respond to these pathogens in ways that are optimal for host survival fitness. The TH1 response to C. muridarum rapidly clears infection, but is inappropriate, as it was not selected by evolution to prevent Fallopian tube damage [33]. The response to C. trachomatis in the genital tract of women, on the other hand, was selected to prevent uncontrolled bacterial replication from damaging epithelium as well as exuberant inflammation from causing immunopathological destruction of reproductive tract tissue. Because TH2 immunity inhibits the development of more tissue-destructive TH1 and TH17 immunity, it may have bed the response selected by evolution to combat C. trachomatis and other persistent genital tract infections. Although the function of TH 2 immunity in defense against allergens, helminths, and other extracellular pathogens is established, we now hypothesize that TH2 immune responses also dampen the intensity of inflammation elicited by chronic C. trachomatis infection while also controlling the growth of this obligate intracellular bacterium in epithelial tissue of the female genital tract.

HYPOTHESIS IMPLICATIONS FOR VACCINE DEVELOPMENT

C. trachomatis is a ubiquitous sexually transmitted pathogen with a predilection to establish persistent infection, and host defenses in the female genital tract evolved in the constant presence of this bacterium. To optimize the opportunities for survival and transmission, C. trachomatis also evolved to elicit responses that suppress, but do not disarm, host defense. It is quite possible, therefore, that both the character and strength of the immune responses elicited against other sexually transmitted pathogens have been adjusted by evolution to counter the diminution of genital tract inflammatory responses that is sequelae to persistent Chlamydia infection. If our hypothesis is correct, and C. trachomatis stimulates polarization toward TH2 immunity and alternative macrophage activation, then a prophylactic chlamydial vaccine administered to women prior to sexual debut has the potential to heighten reactivity to other sexually transmitted microorganisms, and increase the possibility for immunopathological genital tract damage. Less speculative, development of vaccines that induce strong Chlamydia-specific TH1 memory would similarly increase the probability for collateral tissue damage upon repetitive exposure to C. trachomatis in the female genital tract. Therefore, as ectopic pregnancy and tubal factor infertility are less frequent consequences of C. trachomatis infection in areas of the world that maintain chlamydial infection control programs, development of vaccines that suppress phenotypic expression of disease, versus vaccines that stimulate Chlamydia-specific TH1 memory, may warrant greater emphasis. Though these implications of our hypothesis are both plausible and thought provoking, the more basic and immediate objective should be the elucidation of the specific effector CD4+ T cell subsets induced by genital tract C. trachomatis infection of women, as this is a prerequisite for defining the optimal approach to Chlamydia vaccine development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Pediatrics (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine). Authors declare sponsors had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Sources of support: University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT Authors have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influenced their work to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reiner SL. Development in motion:helper T cells at work. Cell. 2007;129:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:445–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wan YY, Flavell RA. How diverse–-CD4 effector T cells and their functions. J Mol Cell Biol. 2009;1:20–36. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen JE, Maizels RM. Diversity and dialogue in immunity to helminths. Nature Immunol. 2011;11:375–88. doi: 10.1038/nri2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y. The biological functions of T helper 17 celleffector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity. 2008;28:454–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billiau A, Matthys P. Interferon-gamma: a historical perspective. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brodsky IE, Medzhitov R. Targeting of immune signaling networks by bacterial pathogens. Nature Cell Biol. 2009;11:521–26. doi: 10.1038/ncb0509-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham AL, Allen JE, Read AF. Evolutionary causes and consequences of immunopathology. Annu Rev Evol Syst. 2005;36:373–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maizels RM, Yazdanbakhsh M. Immune regulation by helminth parasites: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Nature Rev Immunol. 2003;3:733–44. doi: 10.1038/nri1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anthony RM, Urban JF, Jr, Alem F, Hamed HA, Rozo CT, Boucher JL, Van Rooijen N, Gause WC. Memory TH2 cells induce alternatively activated macrophages to mediate protection against nematode parasites. Nature Med. 2006;12:955–60. doi: 10.1038/nm1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC Grand Rounds: Chlamydia prevention: challenges and strategies for reducing disease burden and sequelae. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:370–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paavonen J, Eggert-Kruse W. Chlamydia trachomatis: impact on human reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5:433–47. doi: 10.1093/humupd/5.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunham RC, Rekart ML. Considerations on Chlamydia trachomatis disease expression. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;55:162–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson HD, Helfand M. Screening for chlamydial infection. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(Suppl 3):95–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molano M, Meijer CJ, Weiderpass E, et al. The natural course of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in asymptomatic Colombian women: a 5-year follow-up study. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:907–16. doi: 10.1086/428287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunham RC, Pourbohloul B, Mak S, White R, Rekart ML. The unexpected impact of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection control program on susceptibility to reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1836–44. doi: 10.1086/497341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rekart ML, Brunham RC. Epidemiology of chlamydial infection: are we losing ground? Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:87–91. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chavez JM, Vicetti Miguel RD, Cherpes TL. Chlamydia trachomatis infection control programs: lessons learned and implications for vaccine development. Inf Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:754060. doi: 10.1155/2011/754060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingalls RR, Rice PA, Qureshi N, Takayama K, Lin JS, Golenbock DT. Theinflammatory cytokine response to Chlamydia trachomatis infection is endotoxin mediated. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3125–30. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3125-3130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reighard SD, Sweet RL, Vicetti Miguel C, et al. Endometrial leukocyte subpopulations associated with Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis genital tract infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:324.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amsen D, Spilankis CG, Flavell RA. How are TH1 and TH2 cells made? Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bettelli E, Korn T, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. Induction and effector functions of TH17 cells. Nature. 2008;453:1051–57. doi: 10.1038/nature07036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages:mechanisms and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 2008;13:453–61. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loke P, Gallagher I, Nair MG, et al. Alternative activation is an innate response to injury that requires CD4+ T cells to be sustained during chronic infection. J Immunol. 2007;179:3926–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caldwell HD, Wood H, Crane D, et al. Polymorphisms in Chlamydia trachomatis tryptophan synthase genes differentiate between genital and ocular isolates. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1757–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen CR, Nguti R, Bukusi EA, et al. Immunoepidemiologic profile of Chlamydia trachomatis infection: importance of heat-shock protein 60 and interferon-gamma. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:591–99. doi: 10.1086/432070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsey KH, Sigar IM, Schripsema JH, et al. Strain and virulence diversity in the mouse pathogen Chlamydia muridarum. Inf Immun. 2009;77:3284–93. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00147-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cain TK, Rank RG. Local Th1-like responses are induced by intravaginal infection of mice with the mouse pneumonitis biovar of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1784–89. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1784-1789.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyairi I, Ramsey KH, Patton DL. Duration of untreated chlamydial genital infection and factors associated with clearance: review of animal studies. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Suppl 2):S96–S103. doi: 10.1086/652393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah AA, Schripsema JH, Imtiaz MT, et al. Histopathologic changes related to fibrotic oviduct occlusion after genital tract infection of mice with Chlamydia muridarum. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:49–56. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000148299.14513.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gottlieb SL, Martin DH, Xu F, Byrne GI, Brunham RC. Summary: The natural history and immunobiology of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection andimplications for Chlamydia control. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Suppl 2):S190–204. doi: 10.1086/652401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boots M. Fight or learn to live with the consequences? Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:248–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]