Abstract

Clostridium difficile testing is shifting from toxin detection to C. difficile detection. Yet, up to 60% of patients with C. difficile by culture test negative for toxins and it is unclear if they are infected or carriers. We reviewed medical records for 7,046 inpatients with a C. difficile toxin test from 2005–2009 to determine the duration of diarrhea and rate of complications and mortality among toxin-positive (toxin+) and toxin− patients. Overall, toxin− patients had less severe diarrhea, fewer diarrhea days and lower mortality (P<0.001, all comparisons) than toxin+ patients. One toxin− patient (n=1/6,121; 0.02%) was diagnosed with pseudomembranous colitis but there were no complications such as megacolon or colectomy for fulminant CDI among toxin− patients. These data suggest that C. difficile-attributable complications are rare among patients testing negative for C. difficile toxins and more studies are needed to evaluate the clinical significance of C. difficile detection in toxin− patients.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, toxin, healthcare associated infection, outcomes, diarrhea

Introduction

C. difficile infection (CDI) is responsible for 25–30% of antibiotic associated diarrhea in healthcare settings and nearly all cases of pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) and megacolon associated with antibiotics (Bartlett 2002); Rupnik et al. 2009). It is estimated that 200,000 to 500,000 cases of CDI occur in acute care facilities in the United States each year affecting up to 1% of U.S. hospital admissions (McDonald et al. 2006; Elixhauser and Jhung 2008; Campbell et al. 2009; Jarvis et al. 2009). Yet, accurate diagnosis of CDI remains a significant barrier to treatment and the optimal test is unclear, despite numerous laboratory comparisons (Cohen et al. 2010; Wilcox et al. 2010; Dubberke et al. 2011; Kufelnicka and Kirn 2011).

For decades, C. difficile toxin tests were accepted as an important laboratory adjunct in the diagnosis of CDI because toxins were believed to be responsible for the majority of clinical manifestations and toxin detection helped distinguish C. difficile carriage from CDI (Viscidi et al. 1981; Gerding et al. 1995). Since then, the essential role of C. difficile toxins in CDI pathogenesis has been confirmed and a relationship between toxin concentration and severity has been observed (Kuehne et al. 2010; Akerlund et al. 2006; Lyras et al. 2009; Rupnik et al. 2009; Ryder et al. 2010). Nonetheless, concern that patients with CDI may be missed by reliance on toxin tests has prompted a movement away from toxin testing towards methods that detect toxigenic C. difficile directly, such as PCR and glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) algorithms (Lemee et al. 2004; Peterson et al. 2007; Reller et al. 2007; Gilligan 2008; Sloan et al. 2008; Eastwood et al. 2009; Cohen et al. 2010; Sharp and Gilligan 2010; Tenover et al. 2010; Wilcox et al. 2010; Kufelnicka and Kirn 2011). These tests are more sensitive for C. difficile in toxinsamples, but may be less specific for CDI (Wilcox et al. 2010; Dubberke et al. 2011; Kufelnicka and Kirn 2011). For example, if 20% of hospitalized patients are colonized with C. difficile (Viscidi et al. 1981; McFarland et al. 1989; Samore et al. 1994; Kyne et al. 2000; Cohen et al. 2010) and most nosocomial diarrhea is unrelated to CDI (McFarland 1995); Bartlett 2002; Garey et al. 2006; Yadav et al. 2009), it seems likely that some patients with diarrhea and C. difficile are carriers with diarrhea due to other causes (Wilcox et al. 2010; Kufelnicka and Kirn 2011). Thus, toxin tests may miss occasional patients with CDI while direct tests for C. difficile may result in overdiagnosis and overtreatment. This dilemma points to a critical unmet need to understand the natural history of toxin− patients to inform the C. difficile test debate.

To address this issue, we reviewed the electronic medical records (EMR) of a large cohort of hospitalized patients tested for C. difficile toxins during a period when other C. difficile tests were not performed. Our goals were to compare the frequency of C. difficile-attributable complications and duration of symptoms among toxin− and toxin+ patients as an indication of the number of CDI patients missed by routine toxin tests. The frequency of CDI treatment was also evaluated in both groups with the assumption that empiric treatment in toxin− patients provides an indication of the level of clinical suspicion for CDI.

Materials and Methods

2005 – 2009 dataset

Records from patients ≥1 year old admitted to the UC Davis Medical Center (UCDMC) from January 1, 2005 – December 31, 2009 with a current procedural test code for C. difficile toxin test were analyzed retrospectively. Using the toxin test results, patients and admissions were classified as C. difficile toxin+ or toxin− including tests performed up to 90 days prior to admission and 90 days after discharge. Repeat toxin test results were included. Administrative data, medical, and laboratory records were used to identify patients with PMC diagnosed by endoscopy or histopathology or a CDI-attributable complication (e.g., megacolon, colectomy for fulminant colitis). Specifically, all records with an ICD-9-CM code for rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy (45.23, 45.24, 45.25, 48.23, 48.24), partial or total colectomy (45.79, 45.80) or megacolon (564.7), and all pathology reports with a diagnosis of PMC were individually reviewed. Pre-existing patient comorbidities were enumerated using software available from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) based on the method of Elixhauser et al. (Elixhauser et al. 1998; AHRQ 2011) and crude mortality 6-months after discharge was assessed from UCDMC records.

2009 subset

For admissions between January 1 and December 31, 2009, the duration and severity of diarrheal symptoms and the frequency of CDI-directed treatment among toxin+ and toxin− patients were also assessed. For each admission, stool counts recorded in the EMR were separated into 16-day test episodes beginning two days prior to the date of sample collection for the toxin test. Episodes were analyzed for the number of diarrhea days defined as ≥3 stools per 24-hour period and classified as severe if any day had ≥10 stools recorded. When stool output was recorded as a volume, we divided the volume by 200 mL to estimate the number of bowel movements per day. Patients (episodes) with a peripheral blood white blood cell count ≥15K cells/mm3 within +/− 3 days of the C. difficile sample collection date were classified as having an a leukocytosis. Inpatient pharmacy data for metronidazole and oral vancomycin dispensing were matched with C. difficile episodes and test dates. For toxin− episodes, metronidazole treatment initiated within the 72 hour period, including the day of stool sample collection +/− one day, was classified by manual chart review into one of three categories: 1) empiric therapy for an enteric process or CDI; 2) unrelated to enteric process or CDI; or 3) undetermined. Metronidazole started outside this period was excluded.

Laboratory

C. difficile toxin testing was performed on fresh, diarrheal stool samples using the Premier C. difficile toxins A & B test (Meridian Bioscience) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Other tests such as toxigenic culture or PCR were not performed during the study period. Formed stool samples were tested on physician request.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was limited to the first toxin+ admission or diarrheal episode in the case of toxin+ patients and the first admission or episode in toxin− patients during the study period. The frequencies of categorical variables, such as sex or the proportion of patients with ≥2 comorbidities, a CDI complication, death, or leukocytosis, etc., were compared using the chisquare or Fisher’s exact tests. Non-parametric continuous variables (e.g., age, hospital days, ICU days, diarrhea days, antibiotic days) were compared using the Mann Whitney U test.

Results

From 2005–2009, 7,046 hospitalized patients ≥1 year old were tested for C. difficile toxins during the study period. Of these, 925 (13.1%) tested positive for C. difficile toxins including 914 (98.8%) new onset CDI cases and 11 (1.2%) recurrences; 6,121 (86.9%) patients tested negative for toxins although it is likely that some of these patients had C. difficile not detected by toxin testing (Lemee et al. 2004; Peterson et al. 2007; Reller et al. 2007; Sloan et al. 2008). The characteristics and outcomes of these patients are summarized in Table 1. Overall, toxin+ and toxin− patients had a similar number of pre-existing comorbidities and differed slightly in their age and sex composition. However, toxin+ patients were more frequently admitted to an ICU as part of their hospitalization, had longer lengths of hospital and ICU stay, and had a higher mortality rate than toxin− patients (P<0.001, all comparisons). Five toxin+ patients had histologically confirmed PMC. One toxin− patient was found to have PMC at autopsy but this was a secondary diagnosis and the patient’s death was attributed to hepatorenal syndrome as a complication of cirrhosis and urosepsis. Two toxin+ patients developed a complication of CDI (megacolon, n=1; fulminant CDI requiring colectomy, n=1). No CDI complications were documented among toxin− patients. Taken together, 7 of 925 (0.8%) of toxin+ patients had biopsy confirmed PMC or a complication of CDI versus 1 of 6,121 (0.02%) of toxin− patients (P<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Complications and mortality for toxin-positive and toxin-negative patients (2005–2009)a

| Toxin-positive | Toxin-negative | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 925 | 6121 | |

| Age (median) | 56 | 54 | <0.05 |

| Female (n) | 416 (45.0%) | 2973 (48.6%) | <0.05 |

| ≥2 Comorbidities (n) | 108(11.7%) | 647 (10.6%) | 0.44 |

| Hospital length of stay (days, median) | 17 | 10 | <0.001 |

| ICU stay (n) | 482(52.1%) | 2462 (40.2%) | <0.001 |

| ICU days (median) | 12 | 8 | <0.001 |

| ≥3 C. difficile tests/admission (n) | 308(33.3%) | 1028 (16.8%) | <0.001 |

| CDI discharge code, 008.45 (n)b | 775 (83.8%) | 68(1.1%) | <0.001 |

| Biopsy confirmed PMC or CDI attributable complication (e.g, megacolon, colectomy) (n)c,d |

7 (0.8%) | 1 (0.02%) | <0.001 |

| Death (All causes, 6-month) (n) | 125 (13.5%) | 556(9.1%) | <0.001 |

Analysis limited to the first admission with ≥1 C. difficile test during the study period

ICD-9-CM code for Clostridium difficile infection

Combined cases identified by review of patients with ICD-9-CM codes for rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy (45.23, 45.24, 45.25, 48.23, 48.24), partial or total colectomy (45.79, 45.80) or megacolon (564.7) or pathologic diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis.

Toxin+: PMC (n=5); toxic megacolon (n=1); colectomy for fulminant CDI (n=1); Toxin-: PMC (n=1)

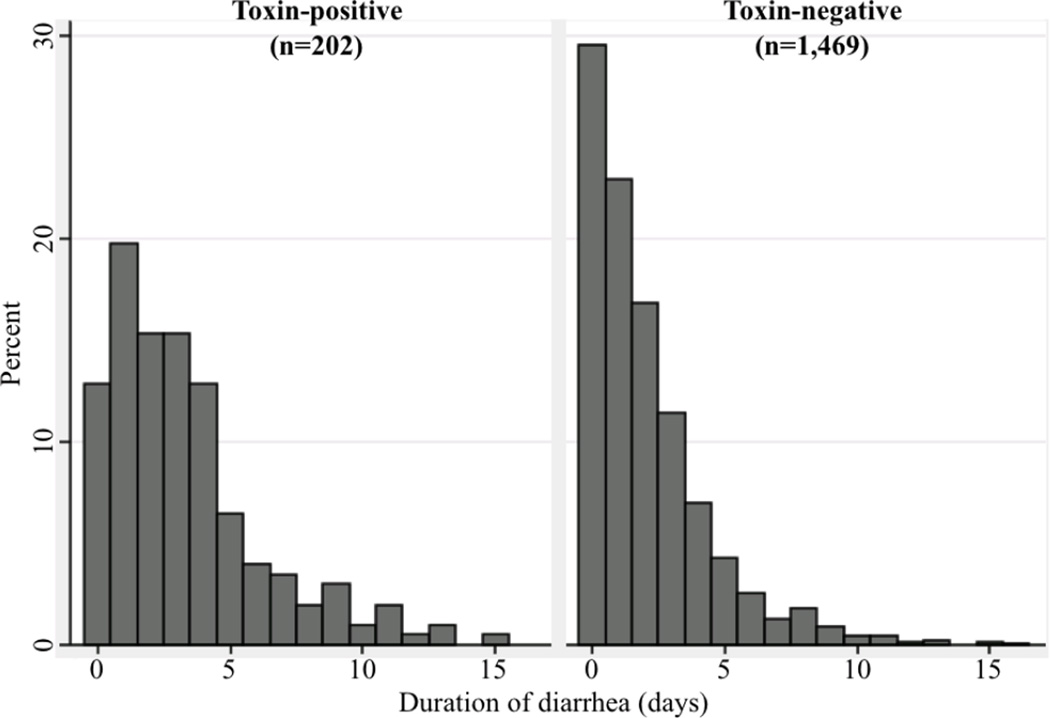

During 2009, 1,671 inpatients had one or more episodes of diarrhea accompanied by a C. difficile toxin test. Using the first positive episode of toxin+ patients and first episode of toxin-patients, 202 (10.7%) toxin+ diarrheal episodes and 1,469 (89.3%) toxin− diarrheal episodes were analyzed. Toxin+ episodes had more days with diarrhea than toxin− episodes (3.3 vs. 2.0 days; P<0.001) and a greater proportion of episodes with severe diarrhea (14.9% toxin+ vs. 8.0% toxin−; P<0.001), leukocytosis (P=0.01), or rectal tube placement (P<0.001) (Table 2). The durations of diarrhea in toxin+ and toxin− episodes are compared in Figure 1. Toxin+ episodes were also longer than the subgroup of toxin− episodes that were treated empirically (n=78, see below) with a mean duration of 3.3 days versus 2.3 days, respectively (P=0.004). To verify that stool count differences were not affected by a recording bias related to the toxin test result, the number of bowel movements during the 48 hours prior to C. difficile toxin testing was also examined. During this period, 35.2% of toxin+ episodes had ≥6 stools during the 48 hours prior to testing versus 27.5% of toxin− episodes (P<0.001), supporting a genuine difference in stool frequency. The median number of tests was 1 in both toxin+ and toxin− episodes but toxin+ episodes had more patients with ≥3 tests/episode (toxin+: n=42/202 (20.8%) vs. toxin−: n=201/1469 (13.7%); P<0.01) indicating that repeat testing was more prevalent among toxin+ patients.

Table 2.

Duration and severity of symptoms for first C. difficile test episode in 1,671 patients (2009)

| Toxin status (patients) | Mean diarrhea daysa [95% CI] |

≥6 stools/ 48 hrs. pre-CDT (%) |

≥10 stools /day (%) |

Rectal tube (%) |

WBC ≥15K/ mm3 (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxin+ (n=202) | 3.3 [2.9, 3.7] | 71 (35.2) | 30(14.9) | 39(19.3) | 85/159(53.5) |

| Toxin− (n= 1,469) | 2.0 [1.9, 2.1] | 404 (27.5) | 118(8.0) | 125(8.5) <0.001 | 569/1330 (42.8) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 |

Diarrhea day defined as ≥3 stools/day during test episode. Medians: Toxin+ = 3 days; Toxin- = 1 day.

Number of episodes with elevated WBC/number with WBC available.

Figure 1.

Duration of diarrhea in toxin-positive and toxin-negative episodes (P<0.001)

Overall, metronidazole or oral vancomycin treatment was started within one day of C. difficile testing in 92.6% (n=187/202) of toxin+ episodes and 14.0% (n=206/1,469) of toxin-episodes (P<0.001) but not all of the toxin− patients received metronidazole as empiric treatment for CDI. Review of the medical records for the 206 toxin− patients with treatment showed that only 5.3% (n=78/1,469) received metronidazole +/− vancomycin empirically for CDI or another enteric process (e.g., parasitic infection, diverticulitis); 7.8% (n=115/1,469) received metronidazole for another specified indication (not CDI); 0.9% (n=13/1,469) received metronidazole without specifying an indication. 86.0% (n=1,263/1,469) of toxin− patients were not treated. In addition to being treated more often, toxin+ patients were treated for a longer period of time in the hospital prior to discharge than toxin− patients who were treated (median duration of inpatient treatment, 5 days (toxin+) versus 2 days (toxin−); P<0.001) and received oral vancomycin more often as well (32.2% of toxin+ episodes versus 1.2% of toxin− episodes; P<0.001).

Discussion

From 2005–2009, we found only one patient among 6,121 toxin− patients (0.02%) with pseudomembranous colitis that was missed by toxin testing and no patients with a documented complication attributable to CDI such as toxic megacolon or fulminant colitis requiring colectomy. Toxin− patients also had a lower rate of mortality at 6 months, shorter hospital lengths of stay, and required less ICU care than toxin+ patients. In our 2009 cohort, toxin-patients had less diarrhea before and after C. difficile testing, and fewer episodes with severe diarrhea or leukocytosis than toxin+ patients, suggesting that toxin− diarrheal episodes were milder. We also evaluated the frequency of empiric treatment among toxin− episodes as an indication of how often physicians’ felt that toxin− patients needed treatment despite a negative test result. Only 5.3% of toxin− episodes were treated empirically in 2009. Taken together, these data suggest that complications of CDI are rare among toxin− patients and toxin− patients have more mild clinical illness than toxin+ patients despite many recent studies emphasizing the number and importance of stool samples with C. difficile that are missed by toxin tests. A hypothesis generated by these results is that toxin−/C. difficile+ patients such as those presumably included among our toxin− patients may be C. difficile carriers who do not need treatment although our study was not designed to answer this question.

As a retrospective study of a period when only a toxin immunoassay was offered clinically, it is a limitation of this study that other tests for C. difficile, such as toxigenic culture, were not performed and the exact number of toxin− patients with C. difficile is unknown. However, we expect that the number of toxin− patients with C. difficile was large and potentially greater than the number of toxin+ patients in light of previous studies (van den Berg et al. 2007; Gilligan 2008; Tenover et al. 2010) and subsequent data from our lab. Recent published studies report sensitivities of 33.3 – 67.5% for the Premier Toxins A & B test relative to toxigenic culture (van den Berg et al. 2007; Gilligan 2008; Tenover et al. 2010) and we recently observed that only 43.3% of stool specimens with C. difficile by real-time PCR (Xpert C. difficile/Epi, Cepheid) or toxigenic culture had toxins detected by the Premier assay at UC Davis (unpublished data). This sensitivity (43.3%) predicts that as many as 1,211 of the toxin− patients in our retrospective cohort may have been C. difficile+ yielding a revised rate of PMC or CDI complication (0.08%) that was still significantly lower than the 0.8% rate that was observed in the toxin+ group between 2005–2009 (P<0.05).

Relatively few studies have examined clinical outcomes in toxin−/C. difficile+ patients but their results generally support the interpretation that most toxin− patients with C. difficile are not actively infected. Gerding et al. found 4 (0.8%) patients with pseudomembranes by endoscopy among 399 toxin− patients of which 3 were positive by toxigenic culture (Gerding et al. 1986). In the same study, the authors noted that 40/43 (93.0%) toxin−/C. difficile+ patients were indistinguishable from controls except for fever (Gerding et al. 1986). At the University of Pittsburgh from 1989–2000, 6 patients with fulminant colitis had a negative toxin assay among 2334 patients with CDI (0.3%) but the number of toxin− and toxin−/C. difficile+ patients was not specified (Dallal et al. 2002). Similarly, Pepin et al. reported that 63 of 1721 (3.7%) CDI cases in Quebec from 1991–2003 were diagnosed by endoscopy or histopathology “without a positive cytotoxin result” but it is not clear if toxin tests were negative for these patients or not performed (Pepin et al. 2004) and toxin−/C. difficile+ patients were not examined. A more recent study limited to cancer patients suggested that toxin+/C. difficile+ and toxin−/C. difficile+ patients were similar in terms of clinical presentation and 30-day mortality but it is unclear how generalizable this study is to other patient populations and other important causes of diarrhea and colitis in cancer patients such as anti-neoplastic agents were not correlated with symptoms (Kaltsas et al. 2012).

Failure to detect toxins may be due to host antibody binding of toxins or low in vivo toxin levels from a lack of toxin production, a low bacterial burden of C. difficile at the time of testing, or a relative predominance of spores versus vegetative cells (Delmee et al. 2005). Rare complications in toxin− patients may also be explained by an excessive host response, preanalytic toxin degradation, or toxin assay insensitivity (Bowman and Riley 1986; Steiner et al. 1997; Tenover et al. 2010; Wilcox et al. 2010). At a higher level, physician testing of minimally symptomatic patients may explain some of our findings including the high proportion of patients with little or no diarrhea and the low rate of complications overall. In a recent evaluation of 150 patients with diarrheal stool samples submitted for toxin testing, only 64% had clinically significant diarrhea and 19% had received laxatives within 48 hours of sample collection, indicating that receipt of a loose stool specimen in the lab is a poor predictor of clinical disease (Dubberke et al. 2011).

This study is unique in examining the frequency of CDI complications, the duration of diarrhea and the frequency of empiric treatment in a large population of patients testing negative for C. difficile toxins. We show that complications of CDI are rare and the duration of diarrhea is shorter in toxin− patients versus toxin+ patients. Thus, while identification of toxin−/C. difficile+ patients may be important for reasons such as infection control (Guerrero et al. 2011), it is unclear at this time whether most toxin− patients with C. difficile are infected or simply carriers. As increasing numbers of laboratories transition to tests that detect C. difficile instead of C. difficile toxins, the incidence of C. difficile is likely to rise dramatically (25–150%) due to detection of C. difficile in samples without detectable toxins. This has major diagnostic, treatment and cost implications for patients, physicians and the healthcare system. Until large-scale clinical outcomes data are available, it may be clinically misleading or inappropriate to assume that all toxin−/C. difficile+ patients have CDI.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This publication was supported in part by Grants Number UL1 RR024146 and TL1 RR024145-06 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

C.R.P. has received materials from Meridian Biosciences, Cepheid and TechLab. All other authors: no conflicts.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Comorbidity Software, Version 3.6, H-CUP. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlund T, Svenungsson B, Lagergren A, Burman LG. Correlation of disease severity with fecal toxin levels in patients with Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and distribution of PCR ribotypes and toxin yields in vitro of corresponding isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:353–358. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.353-358.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:334–339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman RA, Riley TV. Isolation of Clostridium difficile from stored specimens and comparative susceptibility of various tissue culture cell lines to cytotoxin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;34:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RJ, Giljahn L, Machesky K, Cibulskas-White K, Lane LM, Porter K, Paulson JO, Smith FW, McDonald LC. Clostridium difficile infection in Ohio hospitals and nursing homes during 2006. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:526–533. doi: 10.1086/597507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, McDonald LC, Pepin J, Wilcox MH. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA) Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–455. doi: 10.1086/651706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, Sirio CA, Farkas LM, Lee KK, Simmons RL. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235:363–372. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmee M, Van Broeck J, Simon A, Janssens M, Avesani V. Laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea: a plea for culture. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:187–191. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45844-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubberke ER, Han Z, Bobo L, Hink T, Lawrence B, Copper S, Hoppe-Bauer J, Burnham CA, Dunne WM., Jr Impact of Clinical Symptoms on the Interpretation of Diagnostic Assays for Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2887–2893. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00891-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood K, Else P, Charlett A, Wilcox M. Comparison of nine commercially available Clostridium difficile toxin detection assays, a real-time PCR assay for C. difficile tcdB, and a glutamate dehydrogenase detection assay to cytotoxin testing and cytotoxigenic culture methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3211–3217. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01082-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser A, Jhung M. Statistical Brief #50: Clostridium difficile-Associated Disease in U.S. Hospitals, 1993-2005. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey KW, Graham G, Gerard L, Dao T, Jiang ZD, Price M, Dupont HL. Prevalence of diarrhea at a university hospital and association with modifiable risk factors. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1030–1034. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerding DN, Johnson S, Peterson LR, Mulligan ME, Silva J., Jr Clostridium difficileassociated diarrhea and colitis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:459–477. doi: 10.1086/648363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerding DN, Olson MM, Peterson LR, Teasley DG, Gebhard RL, Schwartz ML, Lee JT., Jr Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis in adults. A prospective casecontrolled epidemiologic study. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan PH. Is a two-step glutamate dehyrogenase antigen-cytotoxicity neutralization assay algorithm superior to the premier toxin A and B enzyme immunoassay for laboratory detection of Clostridium difficile? J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1523–1525. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02100-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero DM, Chou C, Jury LA, Nerandzic MM, Cadnum JC, Donskey CJ. Clinical and infection control implications of Clostridium difficile infection with negative enzyme immunoassay for toxin. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:287–290. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis WR, Schlosser J, Jarvis AA, Chinn RY. National point prevalence of Clostridium difficile in US health care facility inpatients, 2008. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltsas A, Simon M, Unruh LH, Son C, Wroblewski D, Musser KA, Sepkowitz K, Babady NE, Kamboj M. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with discordant diagnostic results. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1303–1307. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05711-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne SA, Cartman ST, Heap JT, Kelly ML, Cockayne A, Minton NP. The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection. Nature. 2010;467:711–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufelnicka AM, Kirn TJ. Effective utilization of evolving methods for the laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1451–1457. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:390–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemee L, Dhalluin A, Testelin S, Mattrat MA, Maillard K, Lemeland JF, Pons JL. Multiplex PCR targeting tpi (triose phosphate isomerase), tcdA (Toxin A), and tcdB (Toxin B) genes for toxigenic culture of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5710–5714. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5710-5714.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyras D, O'Connor JR, Howarth PM, Sambol SP, Carter GP, Phumoonna T, Poon R, Adams V, Vedantam G, Johnson S, Gerding DN, Rood JI. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176–1179. doi: 10.1038/nature07822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals, 1996-2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:409–415. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.051064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland LV. Epidemiology of infectious and iatrogenic nosocomial diarrhea in a cohort of general medicine patients. Am J Infect Control. 1995;23:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(95)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, Stamm WE. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:204–210. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901263200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, Villemure P, Pelletier A, Forget K, Pepin K, Chouinard D. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity". CMAJ. 2004;171:466–472. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson LR, Manson RU, Paule SM, Hacek DM, Robicsek A, Thomson RB, Jr, Kaul KL. Detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile in stool samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1152–1160. doi: 10.1086/522185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reller ME, Lema CA, Perl TM, Cai M, Ross TL, Speck KA, Carroll KC. Yield of stool culture with isolate toxin testing versus a two-step algorithm including stool toxin testing for detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3601–3605. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01305-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:526–536. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AB, Huang Y, Li H, Zheng M, Wang X, Stratton CW, Xu X, Tang YW. Assessment of Clostridium difficile infections by quantitative detection of tcdB toxin by use of a real-time cell analysis system. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4129–4134. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01104-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samore MH, DeGirolami PC, Tlucko A, Lichtenberg DA, Melvin ZA, Karchmer AW. Clostridium difficile colonization and diarrhea at a tertiary care hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:181–187. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp S, Gilligan PH. A practical guidance document for the laboratory detection of toxigenicClostridium difficile. ASM Public and Scientific Affairs Board (PSAB) Committee on Laboratory Practices, American Society for Microbiology (ASM); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan LM, Duresko BJ, Gustafson DR, Rosenblatt JE. Comparison of real-time PCR for detection of the tcdC gene with four toxin immunoassays and culture in diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1996–2001. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00032-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner TS, Flores CA, Pizarro TT, Guerrant RL. Fecal lactoferrin, interleukin-1beta, and interleukin-8 are elevated in patients with severe Clostridium difficile colitis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:719–722. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.6.719-722.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover FC, Novak-Weekley S, Woods CW, Peterson LR, Davis T, Schreckenberger P, Fang FC, Dascal A, Gerding DN, Nomura JH, Goering RV, Akerlund T, Weissfeld AS, Baron EJ, Wong E, Marlowe EM, Whitmore J, Persing DH. Impact of strain type on detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile: comparison of molecular diagnostic and enzyme immunoassay approaches. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3719–3724. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00427-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg RJ, Vaessen N, Endtz HP, Schulin T, van der Vorm ER, Kuijper EJ. Evaluation of real-time PCR and conventional diagnostic methods for the detection of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea in a prospective multicentre study. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:36–42. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46680-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viscidi R, Willey S, Bartlett JG. Isolation rates and toxigenic potential of Clostridium difficile isolates from various patient populations. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox MH, Planche T, Fang FC, Gilligan PH. What is the current role of algorithmic approaches for diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection? J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4347–4353. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02028-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav Y, Garey KW, Dao-Tran TK, Kaila V, Gbito KY, DuPont HL. Automated system to identify Clostridium difficile infection among hospitalized patients. J Hosp Infect. 2009;72:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]