Abstract

Long-term acclimation of shade versus sun plants modulates the composition, function and structural organization of the architecture of the thylakoid membrane network. Significantly, these changes in the macroscopic structural organization of shade and sun plant chloroplasts during long-term acclimation are also mimicked following rapid transitions in irradiance: reversible ultrastructural changes in the entire thylakoid membrane network increase the number of grana per chloroplast, but decrease the number of stacked thylakoids per granum in seconds to minutes in leaves. It is proposed that these dynamic changes depend on reversible macro-reorganization of some light-harvesting complex IIb and photosystem II supracomplexes within the plant thylakoid network owing to differential phosphorylation cycles and other biochemical changes known to ensure flexibility in photosynthetic function in vivo. Some lingering grana enigmas remain: elucidation of the mechanisms involved in the dynamic architecture of the thylakoid membrane network under fluctuating irradiance and its implications for function merit extensive further studies.

Keywords: dynamic structure, fluctuating irradiance, grana, lateral heterogeneity, plant thylakoid architecture, thylakoid protein complexes

1. Introduction

The static view of the structural organization of the unique plant thylakoid membrane network inferred from transmission electron micrographs, being but snapshots in time, cannot capture their highly organized and dynamically regulated ultrastructure. To survive and thrive under ever-fluctuating light, plants have evolved long-term acclimation strategies to optimize photosynthetic efficiency and resource utilization [1–3] that are intertwined with vital short-term structural and functional flexibility under fluctuating irradiance [4–7]. Granal stacks in higher plants have been selected during evolution for the integrated, multifaceted advantages and optimization of photosynthesis they confer in diverse and ever-fluctuating light environments [8–11]. In this article, we emphasize that the elaborate dynamic structural changes of more but shorter grana versus fewer but taller grana and vice versa observed in hours, days to seasons in chloroplasts of shade and sun plants are mimicked in seconds to minutes in leaves in response to increasing fluctuating light. Although there have been few examples of snapshots that capture dynamics from experiments with leaves under controlled fluctuating conditions, we suggest that they are caused by the reversible phosphorylation of thylakoid proteins and the various changes associated with non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), the D1 protein repair cycle and the photoprotection of non-functional photosystem II (PSII) under very high irradiance. This highly dynamic regulation of ultrastructure and function of plant thylakoids is intriguing yet still puzzling, especially in the remarkably dynamic three-dimensional architecture of plant thylakoids in vivo. Hence, some lingering grana enigmas concerning the dynamic structural changes in the architecture of the thylakoid network in vivo are also discussed.

2. Supramolecular organization and thylakoid architecture under acclimation and fluctuating irradiance

The highly dynamic structural organization of the continuous thylakoid membrane network of higher plant chloroplasts is intriguing, especially in its elaborate three-dimensional architecture. The continuous thylakoid network that encloses one internal aqueous lumenal space is structurally differentiated into two distinct morphological regions: cylindrical, tightly appressed granal thylakoids (grana stacks) are interconnected by single stromal thylakoids whose outer surfaces face the stroma. This elaborate structural membrane architecture is accompanied by compositional and functional differentiation with respect to the location of the thylakoid pigment–protein complexes termed lateral heterogeneity. PSII/light-harvesting complex II (LHCII) supercomplexes and extra LHCII are mainly segregated in dynamically regulated grana, whereas photosystem I (PSI) and ATP synthase are confined to stromal thylakoids and end granal membranes, while cytochrome (cyt) b6f complexes are reversibly located between stacked and unstacked thylakoid regions ([12–15] and references therein).

Long-term acclimation of plants grown in nature or controlled conditions related to light quantity and quality is well understood [1,2]. With long-term acclimation, the ratio of granal to stromal membrane domains in higher plant chloroplasts is highly variable: the chloroplasts of sun and high-light grown plants have more grana with fewer (5–16) stacked thylakoids per granum, while shade and low-light acclimated plants have fewer grana per chloroplast with more stacked thylakoids, with Alocasia macrorrhiza having giant grana with up to 160 stacked thylakoids [3]. Relative to PSI canopy shade and low-light plants (lower chlorophyll (Chl) a/Chl b ratios) have fewer core PSII complexes served by larger light-harvesting antennae compared with sun and high-light plants (higher Chl a/Chl b ratios) with more core PSII complexes served by smaller light-harvesting antennae; these striking adjustments of the PSII/PSI reaction centre stoichiometry modulate grana stacking [2]. Shade and low-light plants have more chlorophyll for maximal light capture at the expense of electron transport, photophosphorylation and carbon fixation, resulting in lower maximal rates of photosynthesis which saturate at low irradiance. Conversely, sun and high-light plants, being limited in electron transport rather than in light energy capture and conversion, have greater amounts of cyt b6f complexes, ATP synthase and mobile plastoquinone, plastocyanin and ferredoxin, to support greater maximal rates of photosynthesis which saturate at higher irradiance [2]. Many of these modulations of composition are fully reversible [16], and in turn are accompanied by changes in photosynthetic function and thylakoid membrane network organization [2]. These long-term modulations of composition are so beautifully orchestrated that even Chl a/Chl b ratios can serve as simple indices of light intensity acclimation in plants. The Chl a/Chl b ratios of pea leaves are linearly correlated with the content and activity of cyt b6f complex, ATP synthase and Rubisco, but inversely related to LHCII and LHCI content [1,2], and the extent of thylakoid stacking [17].

Acclimation to high irradiance is also linked to the phenomenon of photoinhibition. Although a detailed discussion of photoinhibition is beyond the scope of this article, it should be emphasized that from a functional viewpoint, exposure to excess irradiance brings about a stable, long-term regulation of PSII that may be ‘locked in under sustained high light’, particularly in shade and low-light plants [18,19]. Thus, photoinhibition should be regarded not only as a damaging event, but also as a photoprotective strategy of ecological relevance. Here too, grana may be of critical importance, perhaps preventing premature degradation of D1 and D2 proteins by harbouring non-functional PSIIs deep in appressed thylakoid domains under high irradiance [17].

Besides long-term acclimation (hours, days, weeks or seasons), plants also need reversible, dynamic regulation of photosynthesis from seconds to minutes to allow structure to intertwine with function under fluctuating light quality and quantity. Plants undergo rapid, reversible phosphorylation cycles involving some LHCII and PSII core proteins depending on the interplay between the two main kinases, STN7 and STN8, and their respective phosphatases according to irradiance ([7] and references therein). Low irradiance mainly stimulates phosphorylation of LHCII proteins and, to a lesser extent, some PSII core proteins that cause the STN7 kinase-mediated phosphorylated LHCIIb to laterally migrate from stacked grana to nearby stroma thylakoids, thereby decreasing thylakoid stacking [20,21]. Increasing irradiance induces mainly STN8 kinase-dependent phosphorylation of some PSII core proteins and also the STN7-mediated phosphorylation of the minor antenna complex CP29 [22,23]. Also in high light, the rapid build-up of ΔpH stimulates the activation of violaxanthin de-epoxidase (resulting in accumulation of zeaxanthin) and the protonation of various PSII antenna proteins [4–6]. Together, these cause NPQ, the transformation of LHCII/PSII into a state that dissipates excess light energy. NPQ is accompanied by changes in the structure and organization of the thylakoid membrane [24–26].

3. Dynamic structural changes in grana in leaves under fluctuating irradiance: a grana conundrum

(a). In darkness, antisense Arabidopsis leaves lacking native LHCII trimers have a different thylakoid architecture compared with wild-type leaves

Antisense plants lacking one or more of the six specific PSII antenna Chl a/b proteins usually maintain PSII function but never possess the full orchestral suite of dynamic thylakoid molecular strategies observed in vivo [5]. Arabidopsis antisense plants, asLhcb2, lacking the main LHCIIb trimers involved in grana stacking, increase the content of Lhcb5, which assembles as compensatory Lhcb5 trimers in vivo [27]. These novel trimers function as an alternative PSII antenna enabling somewhat normal macro-organization of PSII supercomplexes to be attained, although the extra LHCIIb-only domains of wild-type chloroplasts are absent. Nevertheless, the asLhcb2 chloroplasts retain well-preserved grana stacking, apparently similar to wild-type chloroplasts [28], although isolated antisense thylakoids are extremely unstable [27,29].

We investigated the architecture of the thylakoid membrane network of chloroplasts within wild-type and asLhcb2 Arabidopsis leaves that were dark-adapted for 15 h, particularly the number of grana per chloroplast and the number of appressed thylakoids per granum. The size and number of grana in two-dimensional thin chloroplast sections from these leaves were assessed by image analysis, according to the method of Rozak et al. [30]. The dark-adapted antisense chloroplasts had an increase of 70 per cent in the number of grana per chloroplast: 63 in antisense chloroplasts compared with 37 in the wild-type (table 1). Concomitantly, in dark-adapted asLhcb2 chloroplasts, the number of appressed thylakoids per granum was diminished by 31 per cent compared with wild-type chloroplasts, resulting in somewhat comparable extents of grana stacking in antisense and wild-type chloroplasts (table 1). Surprisingly, asLhcb2 leaves have smaller chloroplasts (table 1), with each chloroplast possessing more grana with fewer stacked thylakoids per granum than found in wild-type leaves. This unexpected thylakoid profile was not observed visually by Andersson et al. [28] or us until the image analysis was undertaken.

Table 1.

Ultrastructural analysis of chloroplasts of dark-adapted leaves from wild-type and asLhcb2 Arabidopsis, and after 1 h growth light (150 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Fifteen chloroplasts were used for the measurement of height and width in wild-type and asLhcb2, respectively. Values are given as means ± s.e.

| wild-type m | asLhcb2 n | 100 × (n − m)/m | |

|---|---|---|---|

| grana per chloroplast in dark | 37 ± 8 | 63 ± 12 | +70% |

| thylakoids per granum in darka | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | −31% |

| diameter (μm) of grana in dark | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | +2% |

| chloroplast section profile area (μm2) in dark | 15.4 ± 1.5 | 12.2 ± 1.1 | −21% |

| grana per chloroplast in 1 h growth light | 67 | 53 | |

| thylakoids per granum in 1 h growth lightb | 3.9 | 3.9 |

aThe number of thylakoids per granum was calculated by dividing the height by the average thickness of one thylakoid in grana. Granal height, width and cross-sectional area were measured with analySIS program (Olympus Soft Imaging System).

bValues are mean granum sizes calculated from a frequency distribution of the number of thylakoids per granum. Adapted from E-H Kim, PhD thesis, Australian National University, 2006.

Thus, the overall grana membrane architecture of Arabidopsis leaves was profoundly changed in the dark-adapted antisense chloroplasts compared with wild-type chloroplasts. Notably, a gain in grana per chloroplast with a loss of stacked thylakoids per granum, with no difference in the diameter of grana in the dark, means a significant increase in the total granal end membrane area in asLhcb2 chloroplasts compared with that of wild-type chloroplasts.

(b). Dynamic structural changes in Arabidopsis in wild-type and asLhcb2 leaves in response to irradiance

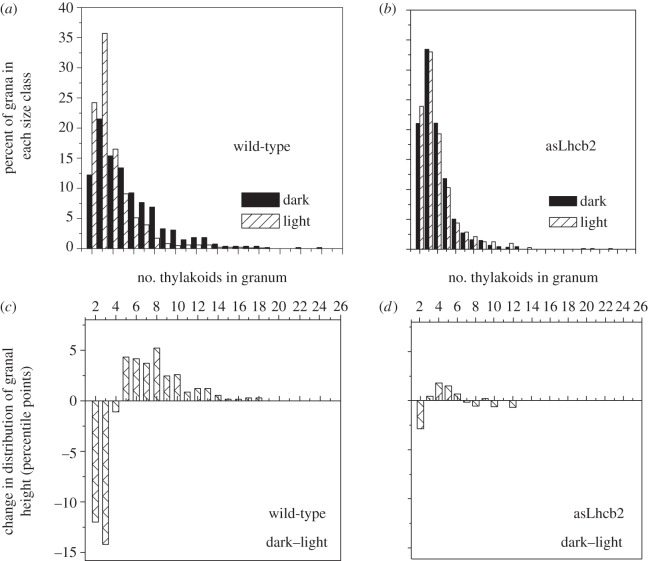

When dark-adapted wild-type Arabidopsis leaves were illuminated under growth light for 1 h to reach steady-state photosynthesis, the number of grana per chloroplast section increased from 37 to 67, while the number of stacked thylakoids per granum decreased from 5.5 to 3.9 (table 1). By contrast, antisense leaves exhibited little or no increase in the number of grana per chloroplast or in the number of stacked thylakoids per granum (table 1). The distribution of granal size (thylakoids per granum) between dark- and light-adapted leaves is shown in figure 1a (for wild-type) and figure 1b (for asLhcb5 leaves). The change in the distribution of granal size in asLhcb2 leaves was hardly shifted between dark and 1 h growth light (figure 1d), in marked contrast to the wild-type (figure 1c). It is remarkable that the grana characteristics of light-adapted plants are now virtually the same in the wild-type and antisense plants. Thus, the antisense plants not only lose the ability to show dynamic changes in grana structure, but also even in the dark-adapted state they resemble the light-adapted state of the wild-type.

Figure 1.

Distribution of granal size (thylakoids per granum) and changes in the distribution of granal size in the dark- and growth light-adapted leaves of wild-type and asLhcb2 Arabidopsis. Granal size distribution: (a) wild-type and (b) asLhcb2. Change in the distribution of granal size from light to dark: (c) wild-type and (d) asLhcb2. The number of grana in each size class was presented as a percentage of the total number of grana in 15 chloroplasts. The total grana number was 551 and 100l in the dark- and light-adapted leaves of wild-type, respectively, and was 951 and 800 in the dark- and light-adapted leaves of asLhcb2, respectively. Adapted from E.-H. Kim, PhD thesis, The Australian National University, 2006.

The explanation of these differences between wild-type and antisense plants resides in the differences in Lhcb and Lhca protein composition. Although Lhcb5-containing S and M trimers accumulate in response to the absence of Lhcb1 and Lhcb2, the additional trimers are absent [27]. Could the loss of these trimers in the antisense plants lead to the constitutive adoption of the light-adapted state found in the wild-type? In the wild-type, the change in grana structure from dark to light almost certainly occurs because of LHCIIb phosphorylation. Therefore, because Lhcb5 lacks a phosphorylation site, it would be predicted that the antisense plants would show no light-induced change in thylakoid stacking. Indeed, the state 1–2 transitions, the expression of changes in antenna organization caused by the reversible LHCIIb phosphorylation, are absent in antisense plants [28]; the plants were found to be locked in state 2, which in wild-type plants is the phosphorylated state. Thus, the depletion of LHCII from the grana, either genetically in the antisense plants or by phosphorylation in the wild-type, underlies the increase in frequency and reduction in size of grana stacks. In addition, the antisense thylakoids also possess an increased content of Lhca1–4 proteins per PSI reaction centre, contributing to a larger PSI antenna, thereby compensating for the absence of phosphorylated LHCII [29]. However, the antisense plants are extremely vulnerable to both rapid ever-changing environmental conditions and very low growth irradiance [31], demonstrating the importance of phosphorylation of LHCII under fluctuating low irradiance and consistent with the requirement for STN7 kinase for optimal growth [7].

(c). Rapid dynamic structural and functional changes in the architecture of the entire thylakoid network in spinach leaves following transitions in irradiance

The remodelling of the grana in Arabidopsis wild-type leaves upon transition from darkness to light is very similar to that observed by Rozak et al. [30], who compared spinach plants before and 10 min after a transition from growth light (300 μmol photons m−2 s−1) with low light or shade (10 μmol photons m−2 s−1 by neutral density shade or self-shading by another leaf). Changes in the overall grana number and size in the attached leaves were quantified by measuring the two-dimensional areas of grana in cross section as seen in transmission electron microscopy thin sections [30]. There is a striking decrease in grana number per chloroplast, but a gain of larger grana (table 2). In particular, transfer to very low irradiance from growth light causes a substantial decrease in the number of grana per chloroplast, but a concomitant increase in the number of appressed thylakoids per grana stack, with a net 9 per cent increase in thylakoid appression (table 2). Consequently, there is a significant decrease in the number of end granal membranes and possibly also the interconnecting stromal thylakoid area. As above, these changes are interpreted in terms of dephosphorylation of LHCII upon transfer to shade, as evidenced by the alteration of the 77 K fluorescence emission spectra [30].

Table 2.

Comparative measurements of the two-dimensional ultrastructural characteristics of chloroplasts from spinach leaves that were light-adapted (2 h at 300 μmol photons −2 s−1) or switched from the light-adapted state to low irradiance/self-shade or higher irradiances. Values are given as means ± s.e.

| light treatment | grana per chloroplast profile | 103 × granum size (µm2) | calculated thylakoid appression (µm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| light-adapted (2 h at 300)a | 44.5 ± 2.1 | 36 ± 1 | 23.4 |

| 10 min of low irradiance (10) | 30.3 ± 1.6 | 49 ± 2 | 25.6 (+9%)b |

| 10 min self-shade (approx. 10) | 32.6 ± 1.4 | 49 ± 2 | 27.5 (+17%) |

| 20 min self-shade (approx. 10) | 30.3 ± 1.6 | 46 ± 2 | 24.0 (+6%) |

| 10 min of 800 μmol m−2 s−1 | 49.2 ± 2.8 | 33 ± 1 | 23.0 (−2%) |

| 10 min of 1500 μmol m−2 s−1 | 46.0 ± 2.0 | 51 ± 2 | 42.0 (+79%) |

aNumbers in brackets in the first column indicate irradiance in μmol photons m−2 s−1.

bValues in parentheses in the last column represent the percentage change from the light-adapted value. From Rozak et al. [30] with permission.

Rozak et al. [30] extended their study to observing plants 10 min after transfer to a moderate irradiance (800 μmol photons m−2 s−1) and also to a very high irradiance (1500 μmol photons m−2 s−1). A shift to moderate irradiance induces a small (statistically not significant) increase in grana per chloroplast and a smaller granal size (table 2), slightly enhancing the character of the growth light state (in comparison with the shade state). In contrast, the shift from growth irradiance to very high irradiance greatly increases granal size with no change in granal frequency. This results in a vast increase in thylakoid appression by 79 per cent relative to that found in the growth irradiance (table 2).

This rapid response to exposure to very high light is intriguing, and deserves further study. Its molecular basis cannot be deduced at present, although we suggest that it is caused by one or more of the biochemical changes that have been recorded upon longer exposure to high irradiance. At high irradiance, the STN7 kinase-mediated phosphorylation of LHCIIb trimers is inhibited [32] and dephosphorylated LHCII would return to the appressed membranes. At the same time, the STN8 kinase induces particularly phosphorylation of certain PSII core proteins, D1, D2, CP43, the PsbH proteins of PSII and the Ca2+-sensing receptor protein [7,23]. As the rate of damage to PSII increases, there is lateral movement of non-functional PSII monomers to nearby stroma-exposed regions for D1 protein repair [33]. A further event occurring in very high light is the phosphorylation of the minor antenna complex CP29 by the STN7 kinase, an event thought to de-stabilize the LHCII/PSII supercomplex [23]. These changes in the balance of phosphoproteins under very high irradiance may well cause the tremendous increase in membrane appression and the accompanying increase in grana size (table 2). However, other features of the thylakoid also change in high light, principally the formation of NPQ. Under the influence of the increased ΔpH, the organization of the PSII/LHCII supercomplexes within stacked granal thylakoids is remodelled; this involves the structural re-organization of some LHCII, which dissociates from PSII supercomplexes, and then is aggregated [5,6,24–26].

The interplay between these responses to high light and how they might influence the granal structure is poorly understood. The return of dephosphorylated LHCIIb proteins to stacked granal domains may help to protect non-functional PSII from further photodamage (via enhancement of NPQ), and elicit some as yet unidentified PSII/LHCII remodelling within the stacked grana domain that is reminiscent of the structural organization found in very low irradiance or darkness. This may be aided by the dissociation of some PSII supercomplexes. Concomitantly, the dominance of phosphorylated PSII core proteins may widen the stromal gap between appressed grana thylakoids to allow photoinactivated PSII supercomplexes in the grana to generate dimeric and then monomeric non-functional PSII units that laterally migrate to nearby stroma-exposed thylakoid domains for D1 protein cycle repair [21,22,33].

(d). Integrated responses of thylakoid membranes to fluctuating irradiance

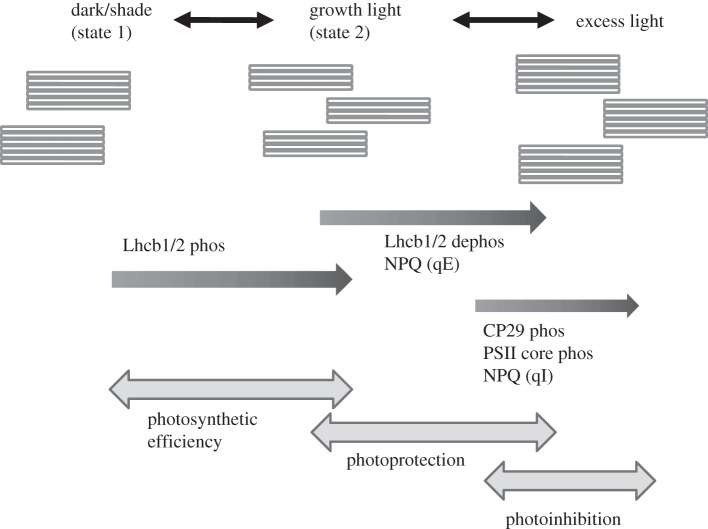

Thus, the number of grana per chloroplast and the number of thylakoids per granum can be reversibly altered within the whole thylakoid membrane network over the entire range of fluctuating irradiances (figure 2). That is, grana provide integrated and multifaceted functional advantages by facilitating mechanisms in a matter of seconds to minutes to cope with rapid fluctuating irradiances that fine-tune the dynamic flexibility of structure with function of the plant thylakoid network in vivo [1,4–6,8,14,15,22–26,30,34,35]. This grand design depends in part on the interplay of the two major kinases that are influenced by light intensity and quality, the STN7-dependent phosphorylation of some LHCII trimers and CP29 versus STN8-dependent phosphorylation of some PSII core proteins, including CP43. These alterations are governed by intricate changes in phosphorylation profiles, according to the redox state of the PQ pool coupled to the redox state of cyt b6f, and stromal redox components beyond PSI [7]. In addition, the ΔpH induces major changes in thylakoid structure that result in NPQ decreasing membrane thickness and inducing LHCIIb aggregation. The extent of each of these events depends upon the initial irradiance, the magnitude of the transition in irradiance and the resulting degree of the rapid perturbation of the redox and energy states of the chloroplast. It should also be remembered that what is low, high or very high irradiance for such dynamic structural changes is different for diverse plant species, and even for the same plant species that have been acclimated mainly to low or high growth irradiance. In all cases, the thylakoid membrane network responds to rapidly maximize the efficiency of photosynthesis in limiting light, while avoiding photodamage in excess light.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the transitions in grana structure and frequency that take place rapidly after a transition in irradiance. Three transition states are depicted—the dark or shaded state (essentially the classical state 1), the state found in steady-state growth light (assumed to be state 2) and the unusual state formed in very high, excess irradiance. Also shown are the major biochemical and organizational changes that are associated with these states, and the estimated irradiance during which they are active. Two types of photoprotection, NPQ, are associated with these different states, rapidly reversible qE and the more sustained qI. These three transition states also mark alteration in photosynthetic physiology: from photosynthetic efficiency, to photoprotection, to the deeper photoprotective state of photoinhibition.

With a dynamic shift from darkness to growth irradiance, fewer grana per chloroplast with more appressed thylakoids per granal stack in dark-adapted attached leaves rapidly reorganize to provide more grana with fewer appressed thylakoids per granal stack to ensure efficient light-harvesting and increased abundance of end granal membranes. Conversely, with a shift from growth irradiance to low light or self-shade, there were fewer grana per chloroplast, but much larger grana. Hence this important structural strategy helps all plants with very different compositions due to acclimation in various light environments to have the same maximum constant quantum yields in limiting light [36,37]. It is thus of particular relevance to note that these rapid short-term, reversible transitions of ultrastructure mimic the long-term, acclimation ultrastructural profiles of shade and low-light plant versus sun and high-light plant chloroplasts. Significantly, alteration in the amount and organization of LHCII in the grana is one of the common biochemical features of both these types of change. Similarly, STN7 kinase is so far the only enzyme known that is common to short-term transitions and long-term acclimation [38].

Clearly, the dynamic macroscopic structural changes of the thylakoid network under fluctuating irradiance need to be further explored. Important questions demand a better understanding of the regulation of flexible three-dimensional molecular architecture of the thylakoid membrane network in vivo, including the following:

— How are more grana per chloroplast with fewer appressed thylakoids per granum converted so rapidly to fewer grana per chloroplast with more appressed thylakoids and vice versa? How does the size of the grana increase so rapidly upon transfer from growth light to very high light? How do the transitions between these very different low light and high light responses occur? These are mind-boggling questions and some insights into the complexity involved have come from structural analysis of chloroplasts in the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated states [39]. Atomic force microscopy, scanning and transmission electron microscopy and confocal imaging reveal marked structural reorganization of the membranes at the interface between the stacked grana and unstacked stromal thylakoids. The reorganization of the membrane architecture is suggested to involve both fission and fusion events similar to those observed in the membranes of mitochondria, Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum [39].

— How do these rapid transitions interface with the acclimation changes that become embedded when the transition in irradiance is sustained?

— Do the chloroplasts of shade-acclimated species differ from those of sun plants in their dynamic ultrastructural responses to fluctuating irradiance? Are the amounts of ‘extra’ Lhcb2 trimers not attached to the PSII/LHCII supercomplexes increased in shade plants?

— In the light, the Mg2+ efflux from the lumen and the cytosol to the stroma is counter-balanced by the Ca2+/H+ antiporter which transports Ca2+ from the stroma to the granal lumen in exchange for a proton efflux [40]. How does this ionic redistribution elicit varying widths of grana lumen and maybe stroma lumen in leaves in darkness or diverse fluctuating irradiances?

— What happens in the LHCII/PSII remodelling in appressed grana thylakoids as dephosphorylated LHCII returns from nearby stroma thylakoid domains upon transition to increasingly high irradiance? Does their reorganization within stacked granal thylakoids enhance photoprotection, particularly of the remaining non-functional PSII centres? Antagonism between LHCIIb phosphorylation and ΔpH-dependent NPQ has been observed, suggesting that dephosphorylation is a prerequisite for maximum quenching [41,42].

‘Given the complexity and pleomorphic nature of the thylakoid lamellar system, deducing its three-dimensional structure from two-dimensional data is precarious’ [15, p. 159]. Further three-dimensional structural studies with leaves under dynamic transient changes in diverse, controlled light conditions are needed.

4. Towards understanding dynamic structural changes in the macroscopic thylakoid structure in vivo: lingering grana enigmas

The exquisite complexity of the three-dimensional architecture of the static thylakoid membrane network is being explored by electron microscope topography [15,43–46]. Recent three-dimensional cryo-tomography work [43–46] confirms the helical model of Paolillo [47] by showing that the stromal thylakoids indeed wind around granal stacks in the form of multiple right-handed helices at an angle of 20–25° with granal membranes. The stromal thylakoids are connected to the appressed granal thylakoids via slits of varying size in the granal margins. These junctional connections between the granal and stromal thylakoids all have slit-like architecture with varying sizes and connect to successive granal pairs by staggered fret-like protrusions. Austin & Staehelin [43] postulate that the ‘tremendous’ width variability in size of the junctional slits may reflect novel, active roles in the functional regulation of many of the dynamic processes of photosynthesis in the context of changes in ultrastructure. However, the first three-dimensional electron tomography microscopy of cryo-immobilized freeze-substituted leaves of dark-adapted lettuce plants led to a model that differs significantly from the prevailing helical models [48]. Instead, grana are built of repeating units that are formed by bifurcations of the stromal lamellar sheets with neighbouring layers connected to each other through bridges located at the bifurcation points at the marginal rim of the grana [15,39,48].

Thus, considerable debate still prevails about the structure of the higher plant thylakoid network, which may be due partly to variation in samples and protocols used in different studies [15]. Further, the use of isolated de-enveloped chloroplasts or even more so isolated thylakoids rather than leaves may disrupt the thylakoid network, but unfortunately leaf sections may often be too large for rapid freezing [49].

These recent insights into the three-dimensional structure of the grana have implication for the relationships between dynamic structural changes and the regulation of photosynthesis, particularly in terms of which specific membrane domains are involved. Current ideas about each of several identified plant thylakoid domains need to be re-examined.

(a). Granal lumen

The granal lumen appears to be narrower (despite its high concentration of PSII oxygen-evolving complex proteins) than the stromal lumen. Kirchhoff et al. [50] examined vitreous sections of unfixed leaf samples of dark- and light-adapted Arabidopsis leaves by cryo-transmission electron microscopy: they demonstrated that the granal thylakoid lumen dramatically expands by 96 per cent from 4.7 nm in the dark to 9.2 nm in the light in vivo. This light-induced expansion of the granal lumen greatly alleviates the restrictions imposed on protein diffusion by increasing protein mobility, especially plastocyanin mobility, in the light; it also aids in the manifold processes associated with the D1 protein repair cycle [50]. This observed expansion of the granal lumen in the light contradicts earlier suggestions following observations on isolated thylakoids [11,51] that the lumen may contract in the light. Conceivably, lumenal contraction or expansion in the light depends on the duration and intensity of illumination. Initially, as Mg2+ exits the lumen driven by a proton influx, the lumenal volume could contract to simultaneously satisfy the conditions of acid–base equilibrium, Donnan equilibrium, osmotic equilibrium and electron neutrality [52]. On the other hand, with prolonged illumination in the presence of Ca2+, the Ca2+/H+ antiporter [40] could accumulate a substantial concentration of Ca2+ accompanied by Cl− in the lumen; such an accumulation of the two ionic species will be accompanied by an influx of water, thereby expanding the lumenal volume.

(b). Granal margins

Recent three-dimensional tomographic data of vitreous sections of intact chloroplasts and plunge-frozen suspensions of isolated thylakoids demonstrated that monomeric ATP synthase is confined to the minimally curved, almost flat stromal regions of end grana membranes and stroma thylakoids [46]. Further three-dimensional tomographic analysis of an isolated granal stack revealed that its granal margins are only 3–4 nm wide [49]. The results from these studies are consistent with the early hypothesis of Murphy [53] that the granal margins are protein-free. Clearly, the granal margins are both too narrow and much too curved to contain membrane-spanning protein complexes. This means that the structural assignment of one of the submembrane fractions isolated by Yeda Press treatment followed by aqueous polymer two-phase partition [54], the so-called granal margins, needs to be reconsidered. Although the composition and functional characterization of ‘granal margin’ fractions have been well demonstrated in many biochemical studies over five decades, their structural assignment as ‘granal margins’ per se is no longer valid.

(c). Stromal thylakoids

Stromal thylakoids are defined as thylakoids whose outer membrane surface is exposed to the stroma, but recent advances in three-dimensional structure suggest that there are instead different regions of stroma-exposed membranes throughout the continuous membrane network: those that are directly linked to granal discs, the junctional connections or frets and the end granal membranes at the top and bottom of each granal stack, which differ from the large sheets of intervening stromal thylakoids that are not so directly linked to granal stacks.

(d). Junctional slits

Recently, the neglected junctional slits that directly link stacked granal thylakoids to stromal lamellae at the granal margins (sometimes glimpsed in two-dimensional electron micrographs as staggered lamellar membrane protrusions from granal thylakoids) are being revealed by three-dimensional cryo-tomography [43,44]. Some stromal thylakoids merge with successive granal discs with approximately 35 nm junctional slits, while others are much wider (approx. 400 nm) so that one stromal thylakoid forms a planar sheet with only one nearby granal disc [43,44]. Are these junctional slits actually the stroma-exposed fraction that has previously been termed ‘granal margins’ [54] and thus the submembrane domain where much of the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation-dependent regulation of excitation energy distribution between PSII and PSI as well as the D1 protein repair cycle occurs?

(e). End granal membranes

The flat stromal-exposed end granal thylakoid sacs are unique; only the outer membrane is exposed to the stroma, while the inner, opposing membrane surface needs to be appressed to the next adjacent grana thylakoid, resulting in different membrane compositions in the opposing membranes facing each other across the lumen of the end granum thylakoid sac. This is an unusual situation. The outer stromal-facing end granal membranes possess monomeric ATP synthase, PSI, cyt b6f and PSIIβ, while the inner opposing membrane facing the lumen contains the oxygen-evolving complexes of the PSII/LHCII arrays.

The transition from darkness to increasing irradiance leads to an increase in end granal membranes seen in the few dynamic structural changes reported here. What functional significance could an increase in end granal membranes have in the rapid restructuring of the entire thylakoid membrane architecture? The more abundant end granal membranes can accommodate more ATP synthase, which would be strategically placed to optimize the proton circuit that drives ATP synthesis. Protons only need to diffuse a short distance to the ATP synthase located in the end granal membranes, when compared with diffusion to an ATP synthase in the distant stromal lamellae. Therefore, an increased abundance of end granal membranes may speed up or increase the efficiency of the proton circuit and photophosphorylation. As for the regulation of linear versus cyclic photophosphorylation under fluctuating irradiance, further experimentation is still needed, not least an accurate method for quantifying cyclic electron flow.

5. Concluding remarks

Although it is not fully understood how the hierarchical assembly of PSII/LHCII supercomplexes in the dark and very low irradiance compares to the hierarchical disassembly of PSII/LHCII supercomplexes under high irradiances, it seems that although functional and structural stability will be enhanced by fewer, but taller grana per chloroplast in the shade and low light, they nevertheless have the capacity for surprisingly highly dynamic structural flexibility in response to transient bursts of high light. This remarkable robustness of plant LHCII/PSII depends on the complementary logic inherent in this marvellous dynamic molecular machine, which is exquisitely regulated both under rapid fluctuating irradiance and long-term acclimation. The structural differentiation of plant thylakoids into stacked granal and unstacked stromal domains is an example of the ‘specialized compartmentation that has occurred during evolution as a strategy to regulate increasingly complicated pathways and achieve both dynamic and long-term control over cellular functions and responses [1]. Thus, grana formation in higher plant chloroplasts fine-tunes photosynthesis by eliciting many dynamic strategies, including the ability to ensure that all plants have constant, high quantum yields at limiting light and balance photochemical utilization with photoprotection by NPQ to regulate maximal linear electron transport, to perform the ingenious D1 protein repair cycle at higher irradiance and to protect non-functional PSIIs ‘parked’ in the stacked granal domains at very high irradiance.

Epilogue

‘We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time’

(T. S. Elliot, The Waste Land 1922)

Acknowledgements

Jan Anderson is extremely grateful to colleagues* who have accompanied her lengthily or briefly during her ‘Why grana’ odyssey in Canberra or on exciting sabbaticals: *Heather Adamson, Bertil Andersson, Eva-Mari Aro, Jack Barrett, Jim Barber, Keith Boardman, Olle Björkman, Jan Brown, Zhong-Xi Chu, Peter Dunkley, John Evans, Robin Hill, Roger Hillier, Peter Horton, Vaughn Hurry, David Goodchild, Eun-Ha Kim, Tony Larkum, Ta-Yan Leong, Paul Levine, Li-Xia Liu, Dick Malkin, Tasso Melis, Gunnar Öquist, Youn-Il Park, John Sinclair, Åke Strid, Cecelia Sundby-Emanuelsson, Bill Thomson, John Thorne and K.C. Woo, particularly her long-time Canberra colleagues, Fred Chow, Barry Osmond and Stephanie McCaffery. We especially also thank Jim Barber, and Brian Gunning for many helpful discussions, and Rob Wise for permission to use data from Rozak et al. [30].

References

- 1.Anderson J. M. 1999. Insights into the consequences of grana stacking of thylakoid membranes in vascular plants: a personal perspective. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 26, 626–639 10.1071/PP99070 (doi:10.1071/PP99070) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson J. M., Chow W. S., Goodchild D. J. 1988. Thylakoid membrane organization in sun/shade acclimation. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 15, 11–26 10.1071/PP9880011 (doi:10.1071/PP9880011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson J. M., Goodchild D. J., Boardman N. K. 1973. Composition of photosystems and chloroplast structure in extreme shade plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 325, 573–585 10.1016/0005-2728(73)90217-X (doi:10.1016/0005-2728(73)90217-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton P., Ruban A. V., Walters R. G. 1996. Regulation of light harvesting in green plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 655–684 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.655 (doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.655) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horton P., Johnson M. P., Perez-Bueno M. L., Kiss A. Z., Ruban A. V. 2008. Photosynthetic acclimation: does the dynamic structure and macro-organisation of photosystem II in higher plant grana membranes regulate light harvesting states? FEBS J. 275, 1069–1079 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06263.x (doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06263.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruban A. V., Johnson M. P., Duffy C. D. P. 2012. The photoprotective molecular switch in the photosystem II antenna. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 167–181 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.007 (doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tikkanen M., Aro E.-M. 2012. Thylakoid protein phosphorylation in dynamic regulation of photosystem II in higher plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 232–238 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.05.005 (doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.05.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horton P. 1999. Are grana necessary for light harvesting regulation? Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 26, 659–669 10.1071/PP99095 (doi:10.1071/PP99095) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow W. S., Kim E.-H., Horton P., Anderson J. M. 2005. Granal stacking of thylakoid membranes in higher plant chloroplasts: the physicochemical forces at work and the functional consequences that ensue. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 4, 1081–1090 10.1039/b507310n (doi:10.1039/b507310n) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullineaux C. W. 2005. Function and evolution of grana. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 521–525 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.09.001 (doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2005.09.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson J. M., Chow W. S., De Las Rivas J. 2008. Dynamic flexibility in the structure and function of photosystem II in higher plant thylakoids: the grana enigma. Photosynth. Res. 98, 575–587 10.1007/s11120-008-9381-3 (doi:10.1007/s11120-008-9381-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staehelin L. A. 2003. Chloroplast structure: from chlorophyll granules to supramolecular architecture of thylakoid membranes. Photosynth. Res. 76, 185–196 10.1023/A:1024994525586 (doi:10.1023/A:1024994525586) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersson B., Anderson J. M. 1980. Lateral heterogeneity in the distribution of chlorophyll–protein complexes of the thylakoid membranes of spinach chloroplasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 593, 427–440 10.1016/0005-2728(80)90078-X (doi:10.1016/0005-2728(80)90078-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekker J. P., Boekema E. J. 2005. Supramolecular organization of thylakoid membrane proteins in green plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1706, 12–39 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.09.009 (doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.09.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nevo R., Charuvi D., Tsabari O., Reich Z. 2012. Composition, architecture and dynamics of the photosynthetic apparatus in higher plants. Plant J. 70, 157–176 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04876.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04876.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melis A. 1991. Dynamics of photosynthetic membrane composition and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1058, 87–106 10.1016/S0005-2728(05)80225-7 (doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(05)80225-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson J. M., Aro E.-M. 1994. Grana stacking and protection of photosystem II in thylakoid membranes of higher plant leaves under sustained high irradiance: an hypothesis. Photosynth. Res. 41, 315–326 10.1007/BF00019409 (doi:10.1007/BF00019409) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Öquist G., Chow W. S., Anderson J. M. 1992. Photoinhibition of photosynthesis represents a mechanism for the long-term regulation of photosystem II. Planta 186, 450–460 10.1007/BF00195327 (doi:10.1007/BF00195327) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Öquist G., Anderson J. M., McCaffery S., Chow W. S. 1992. Mechanistic differences in photoinhibition of sun and shade plants. Planta 188, 422–431 10.1007/BF00192810 (doi:10.1007/BF00192810) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Black M. T., Lee P., Horton P. 1986. Changes in the topography and function of thylakoid membranes following protein phosphorylation. Planta 168, 330–336 10.1007/BF00392357 (doi:10.1007/BF00392357) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tikkanen M., Nurmi M., Suora M., Danielsson R., Mamedov F., Styring S., Aro E.-M. 2008. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of excitation energy distribution between the two photosystems in higher plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 425–432 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.02.001 (doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.02.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fristedt R., Granath P., Vener A. V. 2010. A protein phosphorylation threshold for functional stacking of plant photosynthetic membranes. PLoS ONE 5, e10963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010963 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010963) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fristedt R., Vener A. V. 2011. High light-induced disassembly of Photosystem II supercomplexes in Arabidopsis requires STN7-dependent phosphorylation of CP29. PLoS ONE 6, e24565. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024565 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024565) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kereïche S., Kiss A. Z., Kouřil R., Boekema E. J., Horton P. 2010. The PsbS protein controls the macro-organisation of photosystem II complexes in the grana membranes of higher plant chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. 584, 759–764 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.031 (doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Betterli N., Ballottari M., Zorzan S., de Bianchi S., Cazzaniga S., Dall'Osto L., Morosinotto T., Bassi R. 2009. Light-induced dissociation of an antenna hetero-oligomer is needed for non-photochemical quenching induction. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15 225–15 266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson M. P., Goral T. K., Duffy C. D. P., Brain A. P. R., Mullineaux C. W., Ruban A. V. 2011. Photoprotective energy dissipation involves the reorganization of photosystem II light-harvesting complexes in the grana membranes of spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell 23, 1468–1479 10.1105/tpc.110.081646 (doi:10.1105/tpc.110.081646) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruban A. V., et al. 2003. Plants lacking the main light-harvesting complex retain photosystem II macro-organization. Nature 421, 648–652 10.1038/nature01344 (doi:10.1038/nature01344) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersson J., Wentworth M., Walters R. G., Howard C. A., Ruban A. V., Horton P., Jansson S. 2003. Absence of the Lhcb1 and Lhcb2 proteins of the light-harvesting complex of photosystem II: effects on photosynthesis, grana stacking and fitness. Plant J. 35, 350–361 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01811.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01811.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruban A. V., et al. 2006. Plasticity in the composition of the light harvesting antenna of higher plants preserves structural integrity and biological function. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14 981–14 990 10.1074/jbc.M511415200 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M511415200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozak P. R., Seiser R. M., Wacholtz W. F., Wise R. R. 2002. Rapid, reversible alterations in spinach thylakoid appression upon changes in light intensity. Plant Cell Environ. 25, 421–429 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00823.x (doi:10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00823.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersson J. 2003. Dissecting the photosystem II light-harvesting antenna. PhD thesis, Umeä University, Umeä, Sweden [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rintamäki E., Martinsuo P., Pursiheimo S., Aro E.-M. 2000. Cooperative regulation of light-harvesting complex II phosphorylation via the plastoquinol and ferredoxin-thioredoxin system in chloroplasts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11 644–11 649 10.1073/pnas.180054297 (doi:10.1073/pnas.180054297) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goral T. K., Johnson M. P., Brain A. P. R., Kirchhoff H., Ruban A. V., Mullineaux C. W. 2010. Visualizing the mobility and distribution of chlorophyll proteins in higher plant thylakoid membranes: effects of photoinhibition and protein phosphorylation. Plant J. 62, 948–959 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04207.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04207.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tikkanen M., Grieco M., Kangasjärvi S., Aro E.-M. 2010. Thylakoid protein phosphorylation in higher plant chloroplasts optimizes electron transfer under fluctuating light. Plant Physiol. 152, 723–735 10.1104/pp.109.150250 (doi:10.1104/pp.109.150250) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tikkanen M., Grieco M., Aro E.-M. 2011. Novel insights into plant light-harvesting complex II phosphorylation and 'state transitions’. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 126–131 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.11.006 (doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2010.11.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Björkman O., Demmig B. 1987. Photon yield of O2 evolution and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics at 77 K among vascular plants of diverse origins. Planta 170, 489–504 10.1007/BF00402983 (doi:10.1007/BF00402983) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans J. R. 1987. The dependence of quantum yield on wavelength and growth irradiance. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 14, 69–79 10.1071/PP9870069 (doi:10.1071/PP9870069) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pesaresi P., et al. 2009. Arabidopsis STN7 kinase provides a link between short- and long-term photosynthetic acclimation. Plant Cell 21, 2402–2423 10.1105/tpc.108.064964 (doi:10.1105/tpc.108.064964) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chuartzman S. G., Nevo R., Shimoni E., Charuvi D., Kiss V., Ohad I., Brumfeld V., Reich Z. 2008. Thylakoid membrane remodeling during state transitions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 1029–1039 10.1105/tpc.107.055830 (doi:10.1105/tpc.107.055830) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ettinger W. F., Clear A. M., Fanning K. J., Peck M. L. 1999. Identification of a Ca2+/H+ antiport in the plant chloroplast thylakoid membrane. Plant Physiol. 119, 1379–1385 10.1104/pp.119.4.1379 (doi:10.1104/pp.119.4.1379) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernyhough P., Foyer C. H., Horton P. 1984. Increase in level of thylakoid protein phosphorylation in maize mesophyll chloroplasts by decrease in the transthylakoid pH gradient. FEBS Lett. 176, 133–138 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80927-8 (doi:10.1016/0014-5793(84)80927-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oxborough K., Lee P., Horton P. 1987. Regulation of thylakoid protein phosphorylation by high energy state quenching. FEBS Lett. 221, 211–214 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80927-4 (doi:10.1016/0014-5793(87)80927-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Austin J. R., Staehelin L. A. 2011. Three-dimensional architecture of grana and stroma thylakoids of higher plants as determined by electron tomography. Plant Physiol. 155, 1601–1611 10.1104/pp.110.170647 (doi:10.1104/pp.110.170647) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daum B., Kühlbrandt W. 2011. Electron tomography of plant thylakoid membranes. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 2393–2402 10.1093/jxb/err034 (doi:10.1093/jxb/err034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mustárdy L., Buttle K., Steinbach G., Garab G. 2008. The three-dimensional network of the thylakoid membranes in plants: quasihelical model of the grana-stroma assembly. Plant Cell 20, 2552–2557 10.1105/tpc.108.059147 (doi:10.1105/tpc.108.059147) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daum B., Nicastro D., Austin J., McIntosh J. R., Kühlbrandt W. 2010. Arrangement of photosystem II and ATP synthase in chloroplast membranes of spinach and pea. Plant Cell 22, 1299–1312 10.1105/tpc.109.071431 (doi:10.1105/tpc.109.071431) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paolillo D. J. 1970. The three-dimensional arrangement of intergranal lamellae in chloroplasts. J. Cell Sci. 6, 243–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimoni E., Rav-Hon O., Ohad I., Brumfeld V., Reich Z. 2005. Three-dimensional organization of higher-plant chloroplast thylakoid membranes revealed by electron tomography. Plant Cell 17, 2580–2586 10.1105/tpc.105.035030 (doi:10.1105/tpc.105.035030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kouřil R., Oostergetel G. T., Boekema E. J. 2011. Fine structure of granal thylakoid membrane organization using cryo electron tomography. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807, 368–374 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.11.007 (doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.11.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirchhoff H., Hall C., Wood M., Herbstová M., Tsabari O., Nevo R., Charuvi D., Shimoni E., Reich Z. 2011. Dynamic control of protein diffusion within the granal thylakoid lumen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20 248–20 253 10.1073/pnas.1104141109 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1104141109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albertsson P.-A. 1982. Interaction between the lumenal sides of the thylakoid membrane. FEBS Lett. 149, 186–190 10.1016/0014-5793(82)81098-3 (doi:10.1016/0014-5793(82)81098-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chow W. S., Wagner G., Hope A. B. 1976. Light-dependent redistribution of ions in isolated spinach chloroplasts. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 3, 853–861 10.1071/PP9760853 (doi:10.1071/PP9760853) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy D. J. 1986. The molecular organization of the photosynthetic membranes of higher plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 864, 33–94 10.1016/0304-4157(86)90015-8 (doi:10.1016/0304-4157(86)90015-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albertsson P.-A. 2001. A quantitative model of the domain structure of the photosynthetic membrane. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 349–354 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02021-0 (doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02021-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]