Abstract

Autotomy of body parts offers various prey animals immediate benefits of survival in compensation for considerable costs. I found that a land snail Satsuma caliginosa of populations coexisting with a snail-eating snake Pareas iwasakii survived the snake predation by autotomizing its foot, whereas those out of the snake range rarely survived. Regeneration of a lost foot completed in a few weeks but imposed a delay of shell growth. Imprints of autotomy were found in greater than 10 per cent of S. caliginosa in the snake range but in only less than 1 per cent out of it, simultaneously demonstrating intense predation by the snakes and high efficiency of autotomy for surviving snake predation in the wild. However, in experiments, mature S. caliginosa performed autotomy less frequently. Instead of the costly autotomy, they can use defensive denticles on the inside of their shell apertures. Owing to the constraints from the additive growth of shells, most pulmonate snails can produce these denticles only when they have fully grown up. Thus, this developmental constraint limits the availability of the modified aperture, resulting in ontogenetic switching of the alternative defences. This study illustrates how costs of adaptation operate in the evolution of life-history strategies under developmental constraints

Keywords: anti-predator adaptation, capture–mark–recapture, fitness trade-off, life-history evolution, predator–prey interaction, regeneration

1. Introduction

Natural selection imposed by predators has affected the evolution of life-history strategies in various organisms by allocating resources to adaptive traits under fitness trade-offs [1,2]. However, the availability of an anti-predator trait is often developmentally constrained and may ontogenetically vary independently of fitness trade-offs. Thus, considering developmental constraints—biases of the production of variant phenotypes or limitations on phenotypic variability caused by the structure, character, compositions or dynamics of the developmental systems [3]―may be an important initial step to understanding optimal life-history strategies. Although the benefits of anti-predator adaptations are well documented [4–9], their limitations and costs remain poorly understood [10] because of difficulties in both identifying and quantifying them.

The fact that snail shell morphology changes throughout ontogeny may offer a unique opportunity to test the effects of developmental constraints on the evolution of adaptive traits independently of fitness trade-offs. Most gastropods defend their soft body from predators by constructing hard shells. Growing snail individuals add calcareous materials on the shell edge to extend their portable shelters. Thus, apertures or mouth-openings of shells normally remain vulnerable throughout ontogeny as they would be the favoured site for predator attack. To mechanically impede the enemies' attacks, some snails enclose or thicken their apertures by modifying the growth pattern of their shells [4,11,12]. However, especially in terrestrial pulmonates except a few taxa such as Streptaxidae, modified apertures are available as anti-predator devices only when the snails are mature [13], because of the developmental constraints from the additive growth of the shells.

Autotomy (self-amputation) of body parts is a behaviourally inducible defence common among animals across many taxonomic groups including gastropods, suggesting the ubiquity of its survival advantage [14–18]. However, autotomy subsequently imposes considerable costs usually (but not always) by regenerating the lost parts [19–24], in contrast to other permanent defensive devices such as shells of snails. Thus, other conditions being equal, snails may be expected to ontogenetically switch anti-predator responses from costly autotomy to less-costly structural defences upon maturity, being released from the developmental constraints of the shells.

Here I show an example of the ontogenetic switching of alternative defences from autotomy to apertural barriers in a land snail, Satsuma caliginosa caliginosa (Pulmonata: Camaenidae), specifically against a snail-eating snake, Pareas iwasakii (Colubroidea: Pareatidae). Satsuma caliginosa caliginosa frequently autotomizes its posterior portion of the foot (‘tail’) in response to snake predation, until the alternative morphological defence (apertural barrier) becomes available upon maturity. I further provide field evidence for the functional significance of autotomy in the wild. In addition, a combination of field and laboratory experiments demonstrates a cost of regeneration of a lost foot in the reduced growth rate of shells. This study illustrates how natural selection may affect the evolution of life-history strategies under developmental constraints.

2. Material and methods

Foraging experiments and artificial foot-clipping experiments were conducted at Kyoto University and Tohoku University, respectively. All the data were analysed using R v. 2.15.0 for Windows [25]. Shell diameter was log-transformed.

(a). Study species

Southeast Asian snakes in the Pareatidae are widely regarded as dietary specialists of terrestrial snails and slugs [26]. The Japanese pareatid snake P. iwasakii is endemic to Ishigaki and Iriomote Islands. One of its prey [27], the subtropical land snail S. caliginosa, inhabits Yonaguni Island in addition to these two islands. When it fully grows up, S. caliginosa in populations with the snake (classified as the subspecies S. c. caliginosa) constructs a mound-like structure on the inside of its aperture, whereas those in populations without the snake (Satsuma caliginosa picta) lack such an apertural modification throughout life (figure 1). Adult S. c. caliginosa can survive snake predation without apparent damage using the apertural barrier, but immature S. c. caliginosa and other congeners distributed allopatrically to the snake (Satsuma mercatoria on Okinawa Island and S. c. picta) can hardly do this [12]. All islands are located in the Ryukyu Archipelago, Japan.

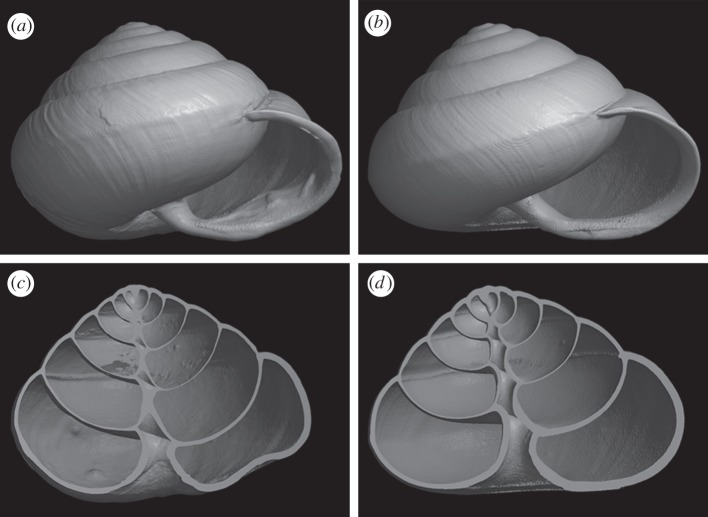

Figure 1.

(a,b) External shapes and (c,d) cross sections of shells of S. caliginosa collected inside ((a,c) S. c. caliginosa) and outside ((b,d) S. c. picta) the distribution range of pareatid snakes.

(b). Foraging experiments

I examined the data used in my previous study where I aimed at testing the defensive function of the apertural barrier of S. c. caliginosa against snake predation [12]. Prey snail species consisted of S. c. caliginosa from one locality on northern Iriomote Island (Funaura; C1 in the electronic supplementary material, figure S1), S. c. picta from a site on eastern Yonaguni Island (Sonai; P2 in the electronic supplementary material, figure S1) and S. mercatoria from two localities on southern Okinawa Island (Nanzan and Chinen). Successful predation was defined as instant death of the prey, and successful survival as survival of the prey for more than one week after a predation experiment, in the same manner as in Hoso & Hori [12]. The latter category was further divided into survival with or without autotomy. Autotomy was defined as the release from the grab with consumption of the distal part of the snail foot by a snake. For details of the experiments and statistical treatments, see the electronic supplementary material.

Autotomy is generally defined as a voluntary shedding of a body part along a breakage plane in response to external stimuli [23]. However, this strict definition cannot be used for body parts of animals without segments, because recognition of ‘voluntary shedding’ and ‘breakage plane’ in such animals is subjective. Therefore, widely accepted examples of autotomy often include those hardly distinguishable from injury imposed by sub-lethal predation. For example, spiny mice autotomize the skin of the tail from the underlying muscles to survive predation, resulting in a naked wound and subsequent necrosis of the tail [18]. The definition of autotomy is especially loose in molluscs [17], partly because breakage planes are not evident in tissues of molluscs that are regarded to perform autotomy [28,29] unlike in musculature segments of lizard tails and in hinges of arthropod appendages. The keys to defining autotomy as an anti-predator mechanism in molluscs are the unsuitability of the predator's feeding apparatus to separate prey body parts and the adaptive significance of the body-part loss induced by predators.

The snakes grabbed the snails with needle-like teeth, which are suitable to hold sticky soft tissue but unsuitable to cut it off [30]. Snakes generally cannot cut prey into small pieces by biting them off [26]; but see [31]. Thus, shedding of a snail foot is probably attributable to an intrinsic mechanism in snails, although the neurophysiological mechanisms remain to be investigated, as in many other cases. More importantly, survival by foot loss would be a by-product of adaptive evolution as demonstrated below in this paper. Thus, it is justified to refer the foot loss by S. caliginosa as autotomy.

(c). Field survey

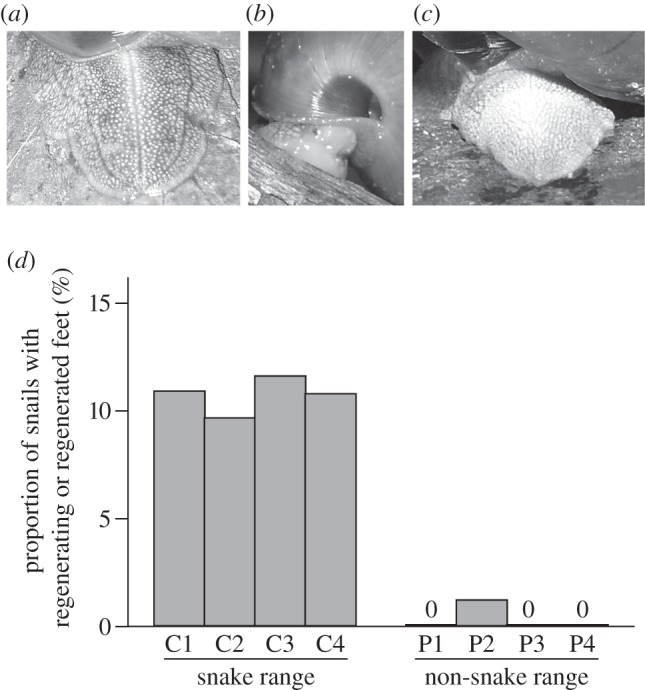

A lost foot required approximately one month to complete regeneration in the laboratory. Regenerated parts of a foot were pale-coloured and lacked an intrinsic groove on the dorsal surface (figure 2a–c). Taking this advantage, I could distinguish a regenerated foot and an intact one. I carried out field surveys on Iriomote, Ishigaki and Yonaguni Islands during 2006 and 2007. I collected S. c. caliginosa and S. c. picta from four populations of each species. Each was assigned to either of two categories: intact or regenerated based on the superficial state of the distal part of the foot. To test the effect of co-occurrence with the snakes on the frequency of foot regeneration within a population, I performed a likelihood-ratio test (LRT) between generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs), where I incorporated localities as a random effect and shell diameter as a covariate to exclude the effect of size difference between these two subspecies of snails. To test the potential effect of foot regeneration in S. c. caliginosa on maturation size, I performed an LRT between the full model and the test model where the effect of foot regeneration was not incorporated.

Figure 2.

(a–c) Foot regeneration of S. caliginosa in the wild. (a) S. caliginosa caliginosa with an intact, (b) a regenerating and (c) a regenerated foot. (d) Proportion of S. caliginosa with a regenerating or regenerated foot in the wild. Each four sampling sites are located within or outside the snake range as seen in the electronic supplementary material, figure S1.

(d). Artificial foot-clipping experiments

To test the negative effects of foot loss on fitness components in S. c. caliginosa, I compared the growth rates of shells of immature snails of which the foot was artificially clipped with a knife to those with an intact foot both in the laboratory and in the field experiments. For details of the experiments and the statistical treatments, see the electronic supplementary material.

3. Results

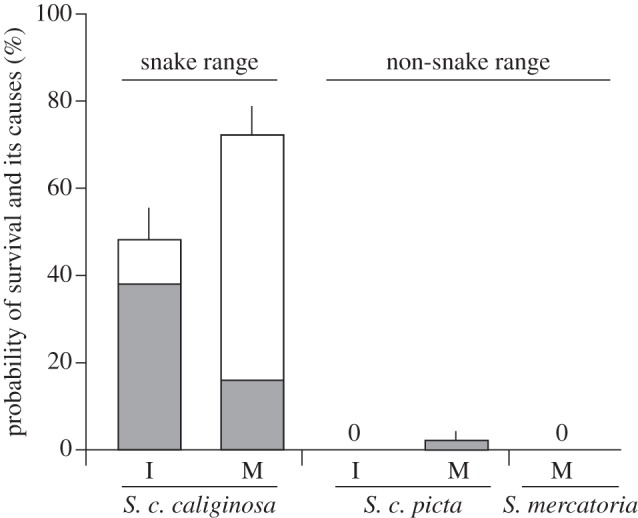

60 ± 12.7% of S. c. caliginosa survived snake predation whereas they all were attacked (means ± s.d. across five snakes, 20 trials for each). 54.6 ± 5.1% of the survivals were attributable to escaping from grab of the snakes with little injury [12], but the other 45.4 per cent survived by autotomizing their feet. Satsuma caliginosa picta and S. mercatoria rarely performed autotomy (LRTs between GLMMs, χ2 = 34.1 and 18.0, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively; figure 3). All snails that successfully survived snake predation were alive for at least a few weeks after being attacked.

Figure 3.

Proportion of successful survival (means across five snakes + 1 s.e.) from predation by P. iwasakii of immature (I) and mature (M) Satsuma snails collected inside and outside the distribution range of pareatid snakes (left and right: S. c. caliginosa, S. c. picta and S. mercatoria). Grey and white bars indicate survival with and without autotomy, respectively.

Comparing Akaike information criteria, the effect of shell size was not selected in the best model in accounting for the probability of survival without autotomy in both datasets. Instead, none of factors and only aperture narrowness were selected in the cases of mature and immature snails, respectively. Aperture shape drastically changes through ontogeny in S. c. caliginosa but exhibits little variation among mature snails (figure 1; [12]). Therefore, the present results strongly indicate the positive effect of aperture shape rather than shell size itself on the probability to survive snake predation without autotomy.

Satsuma caliginosa caliginosa completed regeneration of the consumed foot by approximately one month in captivity. Similarly to the well-known example in lizard tails, regenerated parts of a snail foot were evenly light-coloured and lacked an intrinsic groove on the dorsal surface. These features are distinctive in comparison with intact ones and remain for at least 1 year in the wild. Because the longevity of wild S. c. caliginosa is around or less than 2 years, the stamp of one or more autotomy events probably remains throughout the life of each snail.

Satsuma caliginosa caliginosa with a regenerated or regenerating foot were frequently found with an average of 10.8 per cent across four populations. By contrast, S. c. picta exhibits significantly less occurrence of regeneration (0.3%; LRT between GLMMs, χ2 = 8.24, p < 0.001; figure 2d). Mature S. c caliginosa with an intact and regenerated foot did not significantly differ in maximum shell diameter (LRT between GLMMs, χ2 = 1.19, p = 0.27).

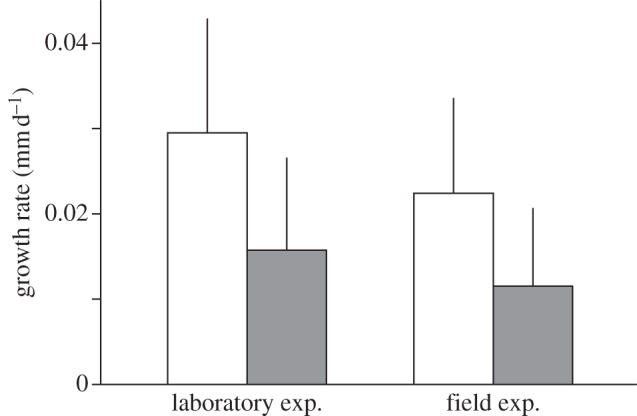

Foot-clipping resulted in significant delay of shell growth in S. c. caliginosa both in the laboratory and field experiments (LRTs between generalized linear models, χ2 = 16.4 and 7.91, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively; figure 4).

Figure 4.

Growth rates of shells (means (mm d−1) + 1 s.d.) of intact (white) and foot-clipped (grey) snails in the laboratory and field experiments.

All the data analysed here are deposited in the electronic supplementary material.

4. Discussion

Autotomy was frequently observed in S. c. caliginosa (S. caliginosa of populations within the snake range), but rarely in S. c. picta (S. caliginosa of populations outside it) and S. mercatoria. Congruently with this result, snails with a regenerated foot were found in S. c. caliginosa at a high frequency. Foot autotomy would be useless for snails to survive predation by enemies that can break the shell (e.g. ruddy kingfishers) or that can invade into the shell through the aperture (e.g. larvae of fireflies). Thus, I do not consider the possibility that predators other than the snake are responsible for the evolution of snail autotomy. Moreover, faunas of snail eaters other than the snake do not markedly differ between these regions. These results indicate that autotomy of the posterior foot in S. caliginosa serves as an anti-predator mechanism specifically against predation by the snail-eating snake P. iwasakii.

Healed wounds on body surfaces of animals often indicate survival experiences from attacks by predators, providing researchers with valuable information on predation pressure in the wild [32–34]. The field data on the frequency of snails with a regenerated foot demonstrate both high efficiency of snail autotomy and high intensity of snake predation on the snails in the wild. Although the frequency of individuals with regenerated body parts also depends on the mortality rate of prey in the face of predation and is not always a reliable indicator of predation intensity [35,36], this is not the case because of the binary comparison between populations with and without the snake predator.

Autotomy can offer snails not only immediate benefits of survival but also additional opportunities for reproduction. All autotomized snails remained alive at least for a few weeks in the laboratory. Artificially foot-clipped snails were recaptured in the field at an even higher rate (11 of 18) than intact snails (seven of 16), suggesting negligible increase of mortality by foot loss. Together with the field observations of mature snails with a regenerated foot, capability of autotomy probably contributes to higher fitness after being attacked by the snakes. Snake predation is an important selective agent for shell traits of the snail genus Satsuma [37], especially of S. c. caliginosa [12]. Thus, the capacity for autotomy by S. c. caliginosa is probably a product of adaptive evolution against snake predation.

Foot autotomy in gastropods has been considered to evolve in parallel with the gradual loss of the protective shell, because the capability of foot autotomy is generally limited in species that cannot withdraw completely into a protective shell [17,38]. The recently discovered foot-autotomy in intertidal Agaronia species until now represented the only exception for the above evolutionary scenario, suggesting an essential role for loss of the opercula, instead of the shells, in the evolution of foot autotomy in gastropods [29]. Similarly, foot autotomy in terrestrial gastropods had been known only in several species of shell-less slugs, and is usually induced by attacks by carabid beetles [39–41]. Satsuma caliginosa caliginosa belongs to the Pulmonata, of which the species lack opercula. Thus, this study adds a new example of foot autotomy in operculum-less snails with a shell large enough to completely cover the soft body.

Foot autotomy may be found in various land snails co-occuring with snail-eating snakes. Snail-eating specialization is not limited to Pareatidae but has arisen multiple times in geographically and genetically distant lineages of snakes. For example, Neotropical snakes of the tribe Dipsadini also feed on snails, similar to pareatid snakes [42]. Thus, foot autotomy of land snails may be found in various land snails co-occurring with snail-eating snakes and would constitute a part of unexplored diversity of predator–prey interactions in the tropics.

Autotomy imposes energetic costs requiring resource and time for the recovery of the lost appendages [19,22,43–45]. Foot-clipping experiments showed that foot loss resulted in the delay of shell growth of snails, elucidating a part of costs of foot autotomy. The maturation size of S. c. caliginosa does not vary, depending on the experience of foot loss in the field. Thus, the cost of autotomy may not bring about drastic changes in their reproductive strategy other than the delay of maturation, although further careful studies are needed to fully understand the consequences of autotomy on the latter life and fitness [46].

Although it was not directly tested in this study because of the rare occurrence of survival without autotomy in immature S. c. caliginosa, the structural defence presumably imposes lower costs than autotomy for surviving predation. As figure 1 shows, only a small amount of additional materials are used to construct the apertural barrier. If structural defence imposes relatively high costs, then foot autotomy should be more widespread even in snails with the capability of structural defence. In addition, there is no evidence to assume the ontogenetic increase of facility to intake the materials and/or construct the barrier. This contrast in costs may drive the adaptive switching of anti-predator mechanisms from autotomy to apertural barriers in S. c. caliginosa. Indeed, mature S. c. caliginosa with apertural barriers less frequently performed autotomy than immature snails without them. This suggests the ontogenetic release of an alternative less-costly defensive mechanism from developmental constraints.

Developmental timing of defensive organs in snails has been viewed in the light of optimal resource allocation [47]. More generally, optimal theories for time and resource allocation trade-offs have been central to understanding life-history strategies under predation risks [8]. Indeed, several studies demonstrate that defensive traits are most pronounced during the ontogenetic stages where the net benefits are largest [48–50]. In this study, however, costs and availability of adaptive traits deterministically explain the ontogenetic switching of alternative defences in a snail against a major snake predator without considering any fitness trade-off. This study thus suggests the importance of identifying and quantifying costs and limits of adaptive traits prior to exploring life-history evolution in the framework of optimal theories.

Acknowledgements

The research was carried out in accordance with the Regulations on Animal Experimentation at Kyoto University and the Regulations for Animal Experiments and Related Activities at Tohoku University, and complied with current laws in Japan.

I thank H. Ota for providing live snakes and M. Schilthuizen for comments on writing the manuscript. I also thank M. Kawai, Y. Kawai and Iriomote Station of the Tropical Biosphere Research Center for the helpful facilities in the field. CT-scanning data were provided through the courtesy of O. Sasaki. This work was partly supported by a JSPS post-doctoral fellowship for research abroad.

References

- 1.DeWitt T. J., Sih A., Hucko J. A. 1999. Trait compensation and cospecialization in a freshwater snail: size, shape and antipredator behaviour. Anim. Behav. 58, 397–407 10.1006/anbe.1999.1158 (doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1158) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West-Eberhard M. J. 2003. Developmental plasticity and evolution. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maynard Smith J., Burian R., Kauffman S., Alberch P., Campbell J., Goodwin B., Lande R., Raup D., Wolpert L. 1985. Developmental constraints and evolution. Q. Rev. Biol. 60, 265–287 10.1086/414425 (doi:10.1086/414425) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermeij G. J. 1987. Evolution and escalation: an ecological history of life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edmunds M. 1976. Defence in animals. London, UK: Longman [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey P. H., Greenwood P. J. 1978. Anti-predator defense strategies: some evolutionary problems. In Behavioural ecology: an evolutionary approach (eds Krebs J. R., Davies N. B.), pp. 129–151 Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific [Google Scholar]

- 7.Endler J. A. 1986. Defense against predators. In Predator–prey relationships: perspectives and approaches from the study of lower vertebrates (eds Feder M. E., Lauder G. E.), p. 198 Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steiner U. K., Pfeiffer T. 2007. Optimizing time and resource allocation trade-offs for investment into morphological and behavioral defense. Am. Nat. 169, 118–129 10.1086/509939 (doi:10.1086/509939) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tollrian R., Haruell C. D. 1999. The ecology and evolution of inducible defenses. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 10.Relyea R. A. 2002. Costs of phenotypic plasticity. Am Nat. 159, 272–282 10.1086/338540 (doi:10.1086/338540) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermeij G. J. 1993. A natural history of shells. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoso M., Hori M. 2008. Divergent shell shape as an antipredator adaptation in tropical land snails. Am. Nat. 172, 726–732 10.1086/591681 (doi:10.1086/591681) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gittenberger E. 1996. Adaptations of the aperture in terrestrial gastropod-pulmonate shells. Neth. J. Zool. 46, 191–205 10.1163/156854295X00159 (doi:10.1163/156854295X00159) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dial B. E., Fitzpatrick L. C. 1984. Predator escape success in tailed versus tailless Scincella lateralis (Sauria: Scincidae). Anim. Behav. 32, 301–302 10.1016/S0003-3472(84)80356-5 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(84)80356-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsay K., Kaiser M. J., Richardson C. A. 2001. Invest in arms: behavioural and energetic implications of multiple autotomy in starfish (Asterias rubens). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 50, 360–365 10.1007/s002650100372 (doi:10.1007/s002650100372) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Formanowicz D. R. 1990. The antipredator efficacy of spider leg autotomy. Anim. Behav. 40, 400–401 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80936-4 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80936-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stasek C. R. 1967. Autotomy in the Mollusca. Occas. Pap. Calif. Acad. Sci. 61, 1–44 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shargal E., Rath-Wolfson L., Kronfeld N., Dayan T. 1999. Ecological and histological aspects of tail loss in spiny mice (Rodentia: Muridae, Acomys) with a review of its occurrence in rodents. J. Zool. 249, 187–193 (doi:10.1111/j.1469–7998.1999.tb00757.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juanes F., Smith L. D. 1995. The ecological consequences of limb damage and loss in decapod crustaceans: a review and prospectus. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 193, 197–223 10.1016/0022-0981(95)00118-2 (doi:10.1016/0022-0981(95)00118-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clause A. R., Capaldi E. A. 2006. Caudal autotomy and regeneration in lizards. J. Exp. Zool. A Comp. Exp. Biol. 305A, 965–973 10.1002/jez.a.346 (doi:10.1002/jez.a.346) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold E. N. 1988. Caudal autotomy as a defense. In Biology of the Reptilia (eds Gans C., Huey R. B.), pp. 235–273 New York, NY: Alan, R. Liss [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maginnis T. L. 2006. The costs of autotomy and regeneration in animals: a review and framework for future research. Behav. Ecol. 17, 857–872 10.1093/beheco/arl010 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arl010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleming P. A., Muller D., Bateman P. W. 2007. Leave it all behind: a taxonomic perspective of autotomy in invertebrates. Biol. Rev. 82, 481–510 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00020.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00020.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bateman P. W., Fleming P. A. 2009. To cut a long tail short: a review of lizard caudal autotomy studies carried out over the last 20 years. J. Zool. 277, 1–14 (doi:10.1111/j.1469–7998.2008.00484.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Development Core Team 2012. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, 2.15.0 edn Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cundall D., Greene H. W. 2000. Feeding in snakes. In Feeding: form, function, and evolution in tetrapod vertebrates (ed. Schwenk K.), pp. 293–333 San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoso M., Hori M. 2006. Identification of molluscan prey from feces of Iwasaki's slug snake, Pareas iwasakii. Herpetol. Rev. 37, 174–176 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L. L., Wang S. P. 2002. Histology and biochemical composition of the autotomy mantle of Ficus ficus (Mesogastropoda: Ficidae). Acta Zool. 83, 111–116 10.1046/j.1463-6395.2002.00106.x (doi:10.1046/j.1463-6395.2002.00106.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rupert S. D., Peters W. S. 2011. Autotomy of the posterior foot in Agaronia (Caenogastropoda: Olividae) occurs in animals that are fully withdrawn into their shells. J. Molluscan Stud. 77, 437–440 10.1093/mollus/eyr019 (doi:10.1093/mollus/eyr019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savitzky A. H. 1983. Coadapted character complexes among snakes: fossoriality, piscivory, and durophagy. Am. Zool. 23, 397–409 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayne B. C., Voris H. K., Ng P. K. L. 2002. Herpetology: snake circumvents constraints on prey size. Nature 418, 143. 10.1038/418143a (doi:10.1038/418143a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohsaki N. 1995. Preferential predation of female butterflies and the evolution of Batesian mimicry. Nature 378, 173–175 10.1038/378173a0 (doi:10.1038/378173a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vermeij G. J. 1982. Unsuccessful predation and evolution. Am. Nat. 120, 701–720 10.1086/284025 (doi:10.1086/284025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savage J. M., Slowinski J. B. 1996. Evolution of coloration, urotomy and coral snake mimicry in the snake genus Scaphiodontophis (Serpentes: Colubridae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 57, 129–194 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1996.tb01833.x (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1996.tb01833.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaksic F. M., Greene H. W. 1984. Empirical evidence of non-correlation between tail loss frequency and predation intensity on lizards. Oikos 42, 407–410 10.2307/3544414 (doi:10.2307/3544414) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medel R. G., Jimenez J. E., Fox S. F., Jaksic F. M. 1988. Experimental evidence that high population frequencies of lizard tail autotomy indicate inefficient predation. Oikos 53, 321–324 10.2307/3565531 (doi:10.2307/3565531) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoso M., Kameda Y., Wu S. P., Asami T., Kato M., Hori M. 2010. A speciation gene for left-right reversal in snails results in anti-predator adaptation. Nat. Commun. 1, 133. 10.1038/ncomms1133 (doi:10.1038/ncomms1133) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fishelson L., Kidron G. 1968. Experiments and observations on the histology and mechanism of autotomy and regeneration in Gena varia (Prosobranchia, Trochidae). J. Exp. Zool. 169, 93–106 10.1002/jez.1401690111 (doi:10.1002/jez.1401690111) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pakarinen E. 1994. Autotomy in arionid and limacid slugs. J. Molluscan Stud. 60, 19–23 10.1093/mollus/60.1.19 (doi:10.1093/mollus/60.1.19) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deyrup-Olsen I., Martin A. W., Paine R. T. 1986. The autotomy escape response of the terrestrial slug Prophysaon foliolatum (Pulmonata, Arionidae). Malacologia 27, 307–311 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foltan P. 2004. Influence of slug defence mechanisms on the prey preferences of the carabid predator Pterostichus melanarius (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 101, 359–364 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sazima I. 1989. Feeding behavior of the snail eating snake, Dipsas indica. J. Herpetol. 23, 464–468 10.2307/1564072 (doi:10.2307/1564072) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapple D. G., Swain R. 2002. Effect of caudal autotomy on locomotor performance in a viviparous skink, Niveoscincus metallicus. Funct. Ecol. 16, 817–825 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00687.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00687.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin J., Avery R. A. 1998. Effects of tail loss on the movement patterns of the lizard, Psammodromus algirus. Funct. Ecol. 12, 794–802 10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00247.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00247.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langkilde T., Alford R. A., Schwarzkopf L. 2005. No behavioural compensation for fitness costs of autotomy in a lizard. Austral. Ecol. 30, 713–718 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2005.01512.x (doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2005.01512.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lind J., Cresswell W. 2005. Determining the fitness consequences of antipredation behavior. Behav. Ecol. 16, 945–956 10.1093/beheco/ari075 (doi:10.1093/beheco/ari075) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irie T., Iwasa Y. 2005. Optimal growth pattern of defensive organs: the diversity of shell growth among mollusks. Am. Nat. 165, 238–249 10.1086/427157 (doi:10.1086/427157) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnqvist G., Johansson F. 1998. Ontogenetic reaction norms of predator-induced defensive morphology in dragonfly larvae. Ecology 79, 1847–1858 10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[1847:ORNOPI]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[1847:ORNOPI]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hawlena D., Boochnik R., Abramsky Z., Bouskila A. 2006. Blue tail and striped body: why do lizards change their infant costume when growing up? Behav. Ecol. 17, 889–896 10.1093/beheco/arl023 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arl023) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wahle R. A. 1992. Body-size dependent antipredator mechanisms of the American lobster. Oikos 65, 52–60 10.2307/3544887 (doi:10.2307/3544887) [DOI] [Google Scholar]