Abstract

Humans, but not chimpanzees, punish unfair offers in ultimatum games, suggesting that fairness concerns evolved sometime after the split between the lineages that gave rise to Homo and Pan. However, nothing is known about fairness concerns in the other Pan species, bonobos. Furthermore, apes do not typically offer food to others, but they do react against theft. We presented a novel game, the ultimatum theft game, to both of our closest living relatives. Bonobos and chimpanzee ‘proposers’ consistently stole food from the responders' portions, but the responders did not reject any non-zero offer. These results support the interpretation that the human sense of fairness is a derived trait.

Keywords: inequity, fairness, ultimatum game, punishment, chimpanzees, bonobos

1. Introduction

People do not behave in a purely self-interested manner. They assess their gains and losses relative to others, and this sensitivity to fairness is an important part of human sociality [1]. Important insights into the evolution of fairness sensitivity come from studies of our closest living relatives. Capuchin monkeys [2] and chimpanzees [3] have been suggested as being averse to disadvantageous inequity, but other studies have not replicated these findings [4,5]. An important shortcoming of all of these studies is that inequity is not created by conspecifics and rejection has no consequences for them.

One powerful tool to probe fairness sensitivity is the ultimatum game [6]. One participant (proposer) can divide a resource with another player (responder); rejection by the latter results in both getting nothing. People in Western societies routinely reject unfair offers of 20 per cent [7], though there is considerable cross-cultural variation [8]. The mini-ultimatum game shares the same features, except the proposer is given a pair of choices, such as a fair (50/50) split paired with an unfair (80/20) division which the responder can accept or reject [9]. A further strength of the mini-ultimatum game is that it tests sensitivity to unfair intentions as well as outcomes by pairing different alternatives against 80/20 [10]. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), the only species tested so far, show no sensitivity to fairness in the mini-ultimatum game, accepting all non-zero offers [11]. A possible limitation of this study is that chimpanzees and other apes do not typically offer food to each other [12], so it may be that unfair intent is not recognized—any offer is a surprise. Chimpanzees, though, are sensitive to food theft and will exhibit signs of anger and punish thieves in response [13]. We capitalized on this sensitivity by designing a novel mini-ultimatum game that involved changes in food allocations being created by the ‘proposer’ stealing a portion of the responder's share. We also tested more socially tolerant bonobos (Pan paniscus) [14] to provide a fuller picture of the evolution of human fairness preferences.

2. Material and methods

We tested five bonobos (two females) and five chimpanzees (four females) at the Wolfgang Köhler Primate Research Centre in Leipzig, Germany. Subjects were tested in their sleeping rooms in adjacent cages which were arranged around a booth that held the test apparatus.

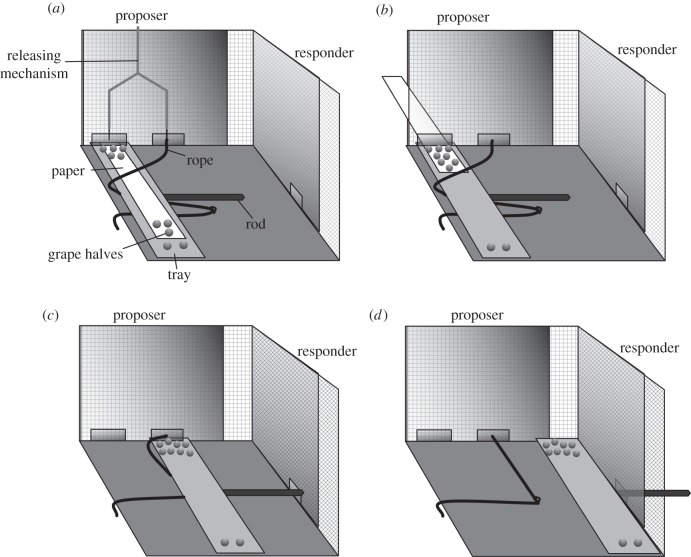

The proposer was behind and to the left of the booth, and the responder was in the cage to the right (figure 1). Once the experimenter left the room, the proposer could pull a piece of paper causing any food on it to be taken from the responder's portion and added to the responder's. This action constituted ‘theft’. The proposer could then pull a rope to move the tray holding the food halfway across the table until a rod was within reach of the responder's cage. The responder could then pull the rod to move the tray the remaining distance. When the rod was pulled, the grape halves became accessible to both subjects. Failure of the responder to pull the rod constituted a rejection. If the proposer did not pull the rope, or if the responder did not pull the rod, after 60 s the experimenter returned and removed the grapes.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the testing procedure using the 5/3;2 game as an example. (a) A paper strip and 10 grape halves are placed on a sliding tray by the experimenter. (b) Pulling the paper results in three of the grape halves that would have gone to the responder being added to the proposer's portion. (c) The proposer pulls the rope (which can be done without pulling the paper), bringing the rod within the responder's reach. (d) The responder can pull the rod, making the food accessible to both subjects. Failure to pull the rod within 1 min results in all the food being removed by the experimenter.

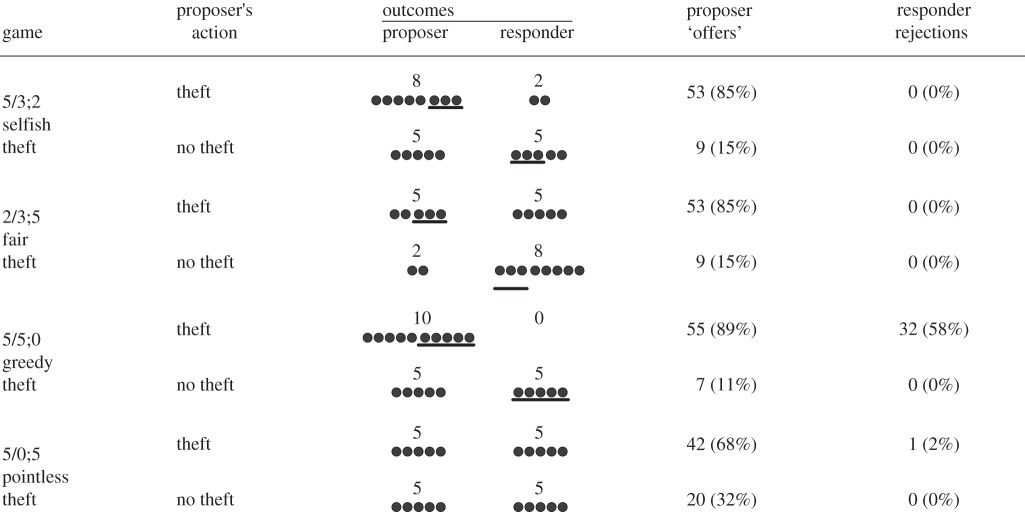

There were four randomly ordered games (trials) per session (table 1). In each game, one possible outcome was a fair split (5/5). In the 5/3;2 (selfish theft) game, if the proposer pulled the paper, she stole three grape halves from the responder's portion and added it to the five she already had, resulting in an 8/2 outcome; doing nothing resulted in an even (5/5) split. Pulling the paper in the 2/3;5 (fair theft) game produced a fair (5/5) division by means of an ‘unfair’ act, whereas not pulling led to a generous (2/8) outcome. The 5/5;0 (greedy theft) game resulted in a hyper-unfair division (10/0) if the paper was pulled, fair (5/5) if it was not. The 5/0;5 (pointless theft) game resulted in a fair (5/5) outcome regardless of whether the paper was pulled or not.

Table 1.

Initial distribution and final outcomes of grape halves in the four games (conditions). The number before the slash is the number of grape halves in the proposer's position, and the numbers after the slash are the responder's with the number before the semicolon being grape halves that can be stolen and the final number being the portion that cannot be stolen. Circles represent grape halves, and those above the line represent the portion that can be pulled away by the proposer. Number and percentage of trials in which grape halves were taken by proposers and rejected by responders are shown for both ape species combined.

|

Non-social controls were presented on alternate days with the test sessions to contrast asocial with other-regarding preferences, and a follow-up probe was given to proposers and responders to gauge their understanding of the task structure, notably inhibition of pulling. All trials were videotaped, and 20 per cent were coded for interobserver reliability (for paper pulling, Cohen's kappa = 0.934; for rod pulling, Cohen's kappa = 1). A Fisher's omnibus test was used to compare species, and one-tailed Wilcoxon tests were used to compare pulling rates against a baseline of 100 per cent (always pulling). For details, see electronic supplementary material.

3. Results

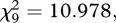

(a). Proposer

Proposers of both species pulled the paper equally often (Fisher's omnibus test, 256 permutations, p = 0.22); therefore, chimpanzee and bonobo data were pooled for subsequent analyses. There were no differences in paper pulling over all games of the social test and the non-social control (Friedman's  p = 0.140, requivalent = 0.570); that is, proposers did not adjust their behaviour for the responders (table 1 and figure 2). Proposers were able to inhibit pulling when there was no food to be gained by pulling the paper in the test (5/0;5 in the test: Wilcoxon T+ = 36, n = 8 (two ties), p = 0.004, requivalent = 0.879, 1-tailed) and in the follow-up probes in which doing so decreased their own portion (T+ = 15, n = 5 (one tie), p = 0.031, requivalent = 0.912, 1-tailed).

p = 0.140, requivalent = 0.570); that is, proposers did not adjust their behaviour for the responders (table 1 and figure 2). Proposers were able to inhibit pulling when there was no food to be gained by pulling the paper in the test (5/0;5 in the test: Wilcoxon T+ = 36, n = 8 (two ties), p = 0.004, requivalent = 0.879, 1-tailed) and in the follow-up probes in which doing so decreased their own portion (T+ = 15, n = 5 (one tie), p = 0.031, requivalent = 0.912, 1-tailed).

Figure 2.

Mean percentage of trials (± 95% CI) in which (a) proposers pulled the paper in the four conditions (games) of the test (grey bars) and the non-social control (white bars) conditions and (b) responders rejected offers by failing to pull the rod for the different possible outcomes in the test and non-social control.

(b). Responder

There was no difference in rates of rejections of bonobos and chimpanzees (Fisher's omnibus test in combination with permutations: 126 permutations, p = 0.83) and species were thus pooled for subsequent analyses (table 1). Whether a portion of the food had been stolen or not, as long as the responders had any amount of food on their side of the tray, they pulled the rod when it was within reach. The only condition in which they inhibited pulling the rod was when there was no food for them (a 10/0 offer in the 5/5;0 game: T+ = 28, n = 7 (two ties), p = 0.008, requivalent = 0.886). This pattern of acceptance was seen in the non-social controls as well, where responders pulled the rod in all conditions and only inhibited pulling when no food was available to them (T+ = 21, n = 6 (three ties), p = 0.016, requivalent = 0.895). The pulling rate for the zero outcome did not differ between the social and non-social control condition (T+ = 24, n = 7 (two ties), p = 0.109, requivalent = 0.657).

Anger, defined as displays and tantrums as in Jensen et al. [13], was rarely exhibited by responders and thus was not analysed statistically.

In the follow-up probe trials, responders consistently pulled the rod to access food from the proposer's position. When no food was available to them, responders inhibited pulling the rod just as they did in previous test and control conditions when they could not gain food (Fisher's omnibus test:  d.f. = 8, p = 0.906).

d.f. = 8, p = 0.906).

4. Discussion

Proposers consistently stole food from responders, without taking into account the effect of their action on their partner, and responders accepted all positive ‘offers’, regardless of outcome and action. This indifference towards the outcome of others when choosing food distributions supports previous findings in chimpanzees [15–17] and extends these to bonobos. Proposers could inhibit pulling the paper when doing so led to the loss of their own food. Despite framing the proposer's decision as ‘theft’, responders still did not forfeit food to punish unfair outcomes or actions. Bonobos and chimpanzees in this study were equally insensitive to inequity. (Small sample sizes may have masked species differences, though there were no suggestive trends.) This finding replicates the result of the previous mini-ultimatum game [11] using a more ecologically salient paradigm and extends the results to the other Pan species.

One possible reason for the lack of rejections by the responders is that they did not feel entitled to the food, which they did not have a sense of ‘ownership’ [18]. Unlike a previous study involving food theft [13], subjects were not eating the food when it was taken away from them. Furthermore, the responders could only reject by not pulling, rather than actively collapsing the tray holding the food. However, it could simply be that the possibility of a food reward overrode any punitive motivation: the great apes in this study may not have been willing to pay a cost to punish unfairness. Future studies could increase the salience of theft and include a more active means of rejection to better tap into the role of anger.

Our conclusion is that bonobos, like chimpanzees, are self-regarding in an ultimatum game that uses unfair actions to produce unfair outcomes. Both apes act like rational maximizers, with no concern for fairness or the effects of their choices on the outcomes affecting others. This finding is very different from what is found in humans, including children [8,9,19]. While humans are strongly affected by concerns for fair allocations and fair intent [9], chimpanzees and bonobos do not appear to be. Concern for fairness and other-regarding preferences may thus be a derived trait in humans [1]. These concerns are likely to have important implications for the evolution of human cooperation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Roger Mundry for statistical advice, Sarah Swenshon for reliability coding and the keepers for their help with the apes.

References

- 1.Fehr E., Fischbacher U. 2003. The nature of human altruism. Nature 425, 785–791 10.1038/nature02043 (doi:10.1038/nature02043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brosnan S. F., de Waal F. B. M. 2003. Monkeys reject unequal pay. Nature 425, 297–299 10.1038/nature01963 (doi:10.1038/nature01963) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brosnan S. F., Schiff H. C., de Waal F. B. M. 2005. Tolerance for inequity may increase with social closeness in chimpanzees. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 253–258 10.1098/rspb.2004.2947 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2947) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bräuer J., Call J., Tomasello M. 2006. Are apes really inequity averse? Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 3123–3128 10.1098/rspb.2006.3693 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3693) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bräuer J., Call J., Tomasello M. 2009. Are apes inequity averse? New data on the token-exchange paradigm. Am. J. Primatol. 71, 175–181 10.1002/ajp.20639 (doi:10.1002/ajp.20639) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Güth W., Schmittberger R., Schwarze B. 1982. An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 3, 367–388 10.1016/0167-2681(82)90011-7 (doi:10.1016/0167-2681(82)90011-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camerer C. F. 2003. Behavioral game theory–experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrich J., et al. 2005. ‘Economic man’ in cross-cultural perspective: behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behav. Brain Sci. 28, 795–815 10.1017/S0140525X05000142 (doi:10.1017/S0140525X05000142) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falk A., Fehr E., Fischbacher U. 2003. On the nature of fair behavior. Econ. Inq. 41, 20–26 10.1093/ei/41.1.20 (doi:10.1093/ei/41.1.20) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falk A., Fischbacher U. 2006. A theory of reciprocity. Game. Econ. Behav. 54, 293–315 10.1016/j.geb.2005.03.001 (doi:10.1016/j.geb.2005.03.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen K., Call J., Tomasello M. 2007. Chimpanzees are rational maximizers in an ultimatum game. Science 318, 107–109 10.1126/science.1145850 (doi:10.1126/science.1145850) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilby I. C. 2006. Meat sharing among the Gombe chimpanzees: harassment and reciprocal exchange. Anim. Behav. 71, 953–963 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.09.009 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.09.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen K., Call J., Tomasello M. 2007. Chimpanzees are vengeful but not spiteful. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 13 046–13 050 10.1073/pnas.0705555104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0705555104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hare B. A., Melis A. P., Woods V., Hastings S., Wrangham R. W. 2007. Tolerance allows bonobos to outperform chimpanzees on a cooperative task. Curr. Biol. 17, 619–623 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.040 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.040) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silk J. B., et al. 2005. Chimpanzees are indifferent to the welfare of unrelated group members. Nature 437, 1357–1359 10.1038/nature04243 (doi:10.1038/nature04243) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vonk J., Brosnan S. F., Silk J. B., Henrich J., Richardson A. S., Lambeth S. P., Schapiro S. J., Povinelli D. J. 2008. Chimpanzees do not take advantage of very low cost opportunities to deliver food to unrelated group members. Anim. Behav. 75, 1757–1770 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.09.036 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.09.036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen K., Hare B., Call J., Tomasello M. 2006. What's in it for me? Self-regard precludes altruism and spite in chimpanzees. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1013–1021 10.1098/rspb.2005.3417 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3417) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kummer H., Cords M. 1991. Cues of ownership in long-tailed macaques, Macaca fascicularis. Anim. Behav. 42, 529–549 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80238-6 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80238-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takagishi H., Kameshima S., Schug J., Koizumi M., Yamagishi T. 2010. Theory of mind enhances preference for fairness. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 105, 130–137 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.09.005 (doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2009.09.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]