Abstract

With 2 to 3% of the worldwide population chronically infected, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection continues to be a major health care burden. Unfortunately, current interferon-based treatment options are not effective in all patients and are associated with significant side effects. Consequently, there is an ongoing need to identify and develop new anti-HCV therapies. Toward this goal, we previously developed a cell-based HCV infection assay for antiviral compound screening based on a low-multiplicity-of-infection approach that uniquely allows for the identification of antiviral compounds that target cell culture-derived HCV (HCVcc) at any step of the viral infection cycle. Using this assay, here we report the screening of the NCI Diversity Set II library, containing 1,974 synthesized chemical compounds, and the identification of compounds with specific anti-HCV activity. In combination with toxicity counterscreening, we identified 30 hits from the compound library, 13 of which showed reproducible and dose-dependent inhibition of HCV with mean therapeutic indices (50% cytotoxic concentration [CC50]/50% effective concentration [EC50]) of greater than 6. Using HCV pseudotype and replicon systems of multiple HCV genotypes, as well as infectious HCVcc-based assembly and secretion analysis, we determined that different compounds within this group of candidate inhibitors target different steps of viral infection. The compounds identified not only will serve as biological probes to study and further dissect the biology of viral infection but also should facilitate the development of new anti-HCV therapeutic treatments.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a hepatotropic enveloped positive-strand RNA virus (family Flaviviridae) that infects the parenchymal cells of the liver (i.e., hepatocytes) (69, 70). HCV infection begins with interaction of the viral particle with the target cell via a relatively undefined multistep process of binding between the virion and multiple cell surface receptors, which include the cluster of differentiation 81 (CD81) tetraspanin protein (7, 34, 56, 80, 84), the scavenger receptor class B member I (SR-BI) (also known as SCARB1) (7, 30, 38, 63, 83), and the tight-junction proteins claudin-1 (CLDN1) (20) and occludin (OCLN) (8, 47, 57). In addition to these four host factors, we more recently showed that the cellular Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) cholesterol uptake receptor also functions as an HCV entry factor via a virion particle cholesterol-associated mechanism (60), and Lupberger et al. have recently shown that the host cellular epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2) function as cofactors during viral cell entry (49).

Following entry, the viral genome (∼9.6 kb) is translated by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-dependent process into a single viral polyprotein that is subsequently co- and posttranslationally cleaved into structural (core, E1, E2, and p7) and nonstructural (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) proteins by host and viral proteases (29, 46). The NS proteins enable replication of the viral RNA (7), which is then encapsidated by the viral core protein and thought to become enveloped as it buds into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The progeny virions are then subsequently released from the cell in association with the host very-low-density lipoprotein secretory pathway (24, 35, 53).

HCV infection is a significant public health burden, as 130 to 180 million individuals worldwide are estimated to be chronically infected. Although acute infection is often asymptomatic and is estimated to be self-limiting in 10 to 30% of infected individuals (1, 59), HCV infection has a strong tendency toward chronicity, with at least 70% of acute infections progressing to chronic hepatitis with risk of long-term associated complications that can lead to end-stage liver disease, such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (4). Notably, increases in HCV cirrhosis have played a major role in the recent rise in HCC and HCC-associated liver transplants worldwide (19). In the United States alone, HCV-related HCC accounts for greater than 50% of all HCC cases and over 40% of liver transplants performed (5).

To date, there is no vaccine against HCV, and combination pegylated alpha interferon (pIFN-α) and ribavirin (27), the main standard-of-care treatment for HCV, is effective in only a subset of patients (2) and is associated with a wide spectrum of toxic side effects and complications (21). However, with the recent clinical release of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) targeting the NS3/4A protease and the expected FDA approval of NS5B polymerase inhibitors within the next year, the future of HCV treatment is expected to significantly improve (69, 70). Nevertheless, with no vaccine available to protect against HCV infection, uncertainty remaining regarding the global effectiveness and availability of new, expensive HCV-specific DAAs (2), and the number of chronically infected HCV patients expected to develop serious liver disease over the next decade (79), there still exists a need for the discovery and development of new HCV inhibitors. In particular, since the future of HCV therapy will likely consist of a cocktail approach using multiple inhibitors that target different steps of infection, new antivirals targeting all steps of the viral infection cycle, particularly HCV entry and egress, for which there are no current FDA-approved drugs, are urgently needed.

We recently reported the development of a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) cell-based HCV infection assay (81), which combines the infectious cell culture-derived HCV (HCVcc) (45, 75, 84) and a novel nondividing Huh7 cell culture system (16, 62) with a sensitive FRET-based readout for the virally encoded NS3/4 enzyme. This assay not only is highly amendable for high-throughput screening (HTS) of compound libraries but is designed to detect inhibitors of all aspects of viral infection due to the low-multiplicity-of-infection (low-MOI)-based approach utilized, which allows for multiple rounds of viral replication and spread (81). Using this assay, we screened the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Diversity Set II library, containing 1,974 synthesized chemical compounds, and identified 18 compounds that showed reproducible, dose-dependent inhibition of HCV in the absence of cytotoxicity. Using follow-up assays to individually assess HCV entry, replication, and secretion, we further determined the step(s) of infection targeted by each candidate compound. Not only may some of these compounds warrant further development as HCV inhibitors, but by having their mechanisms of action identified, they should additionally prove useful as probes to dissect and better understand the biology of HCV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Huh7-1 and 293T cells have been previously described (61). The clone B HCV genotype 1b subgenomic (sg1b) replicon Huh7 cells were obtained from C. M. Rice (Rockefeller University, New York, NY) through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program and have been described previously (9). HCV sg2a (JFH) and sg1a (H77) replicon cells were established as previously described (42, 71) using plasmids encoding the nonstructural region of genotype 2a (pSGR-JFH1) (39) (kindly provided by T. Wakita, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan) or genotype 1a [pH/SG-Neo(L+I)] (10) (kindly provided by C. Rice), respectively. All cells were passaged in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (cDMEM) (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco Invitrogen), and, in the case of HCV subgenomic replicon cells, 500 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen).

JFH-1 cell culture-propagated HCV (HCVcc) viral stocks were obtained by infection of naïve Huh7-1 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 focus-forming units (FFU)/cell, using medium from Huh7-1 cells electroporated with in vitro-transcribed full-length infectious HCV JFH-1 RNA generated from pJFH-1 provided by Takaji Wakita (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously (82).

NSC compound library and reagents.

The National Cancer Institute Diversity Set II compound library, containing 1,974 synthesized chemical compounds resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 10 mM, was obtained in 96-well plate format from the Open Chemical Repository of the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program (http://dtp.cancer.gov). Subsequently, lyophilized compounds of interest were obtained from the same source and were resuspended in DMSO to a concentration of 10 mM. Recombinant human beta interferon (IFN-β) was purchased from PBL Biomedical Laboratories (New Brunswick, NJ) and resuspended to a concentration of 50 U/μl in complete DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The anti-human CD81 monoclonal antibody was purchased from Serotec (Raleigh, NC), and the anti-HCV E2 monoclonal antibody (C1) (43, 84) was kindly provided by M. Law at The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA. The 5-FAM/QXL520 NS3 FRET substrate, an internally quenched peptide with a fluorescent donor (5-carboxyfluorescein [5-FAM]) and acceptor (QXL) on opposing sides of the NS3 protease cleavage site, was purchased from Anaspec (Fremont, CA).

HCVcc FRET assay.

Protocols for the HCVcc FRET assay have been published (82). Briefly, Huh7 cells were seeded in 24 96-well BIOCoat culture black plates with clear bottoms (BD Biosciences) at a density of 8 × 103 cells/well in cDMEM. When the cells reached 90 to 95% confluence, the medium was replaced with 200 μl cDMEM supplemented with 1% DMSO (Sigma), and cells were cultured for an additional 20 days, replacing the medium every 2 days. These cultures are referred to as DMSO-Huh7 cells and have been previously described and characterized (16, 62, 82). For inhibition experiments, DMSO-Huh7 cultures were inoculated with HCVcc JFH-1 at an MOI of 0.05 FFU/cell. Controls consisted of diluent (DMSO)-treated HCVcc-infected cultures, IFN-β (100 U/ml)-treated HCVcc-infected cells, and mock-infected cultures. Experimental wells were treated on days 0, 2, and 4 postinfection (p.i.) with specified NSC compounds at a concentration of 50 μM. On days 2, 4, and 6 p.i., 80 μl of medium was collected from culture plates and stored for subsequent cytotoxicity analysis as described below. On day 6 p.i., cells were lysed in either 50 μl 1.25% Triton X-100 lysis buffer (Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA) or 200 μl 1× nucleic acid purification lysis solution (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and immediately frozen (−80°C). FRET analysis was performed as previously described (81, 82), and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis was performed as described below.

FRET relative fluorescence unit (RFU) values from control or experimental wells were background (BC) corrected using the mock-infected controls and are expressed as a percentage of the maximum BC-corrected FRET activity determined in DMSO-treated HCVcc-infected wells (100% maximum RFU activity). The Z′ was calculated using the equation 1 − [(3σc+ + 3σc−)/(μc+ − μc−)], where 3σc+ is the standard deviation of the signal (diluent treated), 3σc− is the standard deviation of the background (IFN-β treated), μc+ is the average RFU of the signal (diluent treated), and μc− is the average RFU of the background (IFN-β treated).

Cytotoxicity assay.

During all antiviral screens, drug-mediated cellular toxicity was determined on the indicated days posttreatment using the Toxilight BioAssay kit (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), a bioluminescence-based assay which measures adenylate kinase (AK) released from damaged cells into the culture medium, as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Pseudotyped retrovirus production and infections.

Pseudotyped viruses were produced, as previously described (61), by cotransfection of DNA vectors encoding the HCV E1 and E2 glycoproteins of genotype 1a (H77), 1b (Con1), or 2a (JFH) or vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) envelope glycoprotein (G) with an Env-deficient human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vector carrying a luciferase reporter gene (pNL4-3-Luc-R−-E−) into 293T producer cells. The cDNA clone containing E1E2 from genotype 1a strain H77 in pCB6 was provided by Charles Rice (Rockefeller University). The cDNA clone containing E1E2 from genotype 1b strain Con1 and the Env-deficient HIV vector carrying a luciferase reporter gene (pNL4-3-Luc-R−-E−) were provided by Lijun Rong (University of Illinois, Chicago). The cDNA clone containing E1E2 from genotype 2a strain JFH-1 was constructed by subcloning this region from pJFH-1 into pcDNA3.1. Supernatants were collected at 48 h posttransfection, filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (BD Biosciences), aliquoted, and frozen, and titers were subsequently determined using the QuickTiter lentivirus titer kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For inhibition assays, Huh7 cells were seeded in 96-well BIOCoat culture plates (BD Biosciences) and cultured as described above. Prior to infection, cells were treated with indicated compounds for 1.5 h. Parallel sets of triplicate wells were then inoculated with equal titers of JFHpp, H77pp, Con1pp, or VSVGpp in the presence of compound inhibitors, washed twice with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then overlaid with 200 μl cDMEM. At 72 h p.i., cultures were lysed in 20 μl of lysis reagent to measure luciferase activity (Promega, Madison, WI) using a FLUOstar Optima microplate reader (BMG Labtechnologies Inc., Durham, NC). Relative light units (RLU) were BC corrected and normalized to corresponding BC-corrected VSVGpp RLU values: (HCVpp − BC)/(VSVG − BC).

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR analysis.

Total cellular RNA was purified using an ABI Prism 6100 Nucleic Acid PrepStation (Applied Biosystems), as per the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription and RT-qPCR were performed using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems) and FastStart universal SYBR green master mix (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN), respectively, and using the following primers: universal HCV primers (41) 5′-GCC TAG CCA TGG CGT TAG TA −3′ (sense) and 5′-CTC CCG GGG CACTCG CAA GC-3′ (antisense) and human GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (84) 5′-GAA GGT GAA GGT CGG AGT C-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAA GAT GGT GAT GGG ATT TC-3′ (antisense). HCV RNA copies were determined relative to a standard curve comprised of serial dilutions of a plasmid containing the JFH-1 HCV cDNA (pJFH-1).

Extracellular infectivity titration assay.

Cell supernatants were serially diluted 10-fold in cDMEM, and 100 μl was used to infect, in triplicate, 4 × 103 naïve Huh7 cells per well in 96-well plates (BD Biosciences). At 24 hours postinoculation, cells monolayers were overlaid with 150 μl complete DMEM containing 0.4% (wt/vol) methylcellulose (Fluka BioChemika, Switzerland) to give a final concentration of 0.25% methylcellulose, and at 72 h p.i., medium was removed, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), and immunohistochemical staining for HCV E2 was performed as described previously (81). Viral infectivity titers are expressed as FFU per milliliter of supernatant (FFU/ml), determined by the average number of E2-positive foci detected in triplicate samples at the highest HCV-positive dilution.

Cluster analysis of hits.

The structures of 18 hits were imported from Pubchem (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) database (15). The bit-packed MACCS structural keys (BIT_MACCS) fingerprints were generated for all the compounds. The similarity and overlap thresholds were set at 65%. The similarity between the fingerprints was assessed with the Tanimoto superset/subset metric, and the compounds were clustered using the Jarvis-Patrick procedure as implemented in MOE.

RESULTS

Screening of anti-HCV compounds using a cell-based HCVcc infection assay.

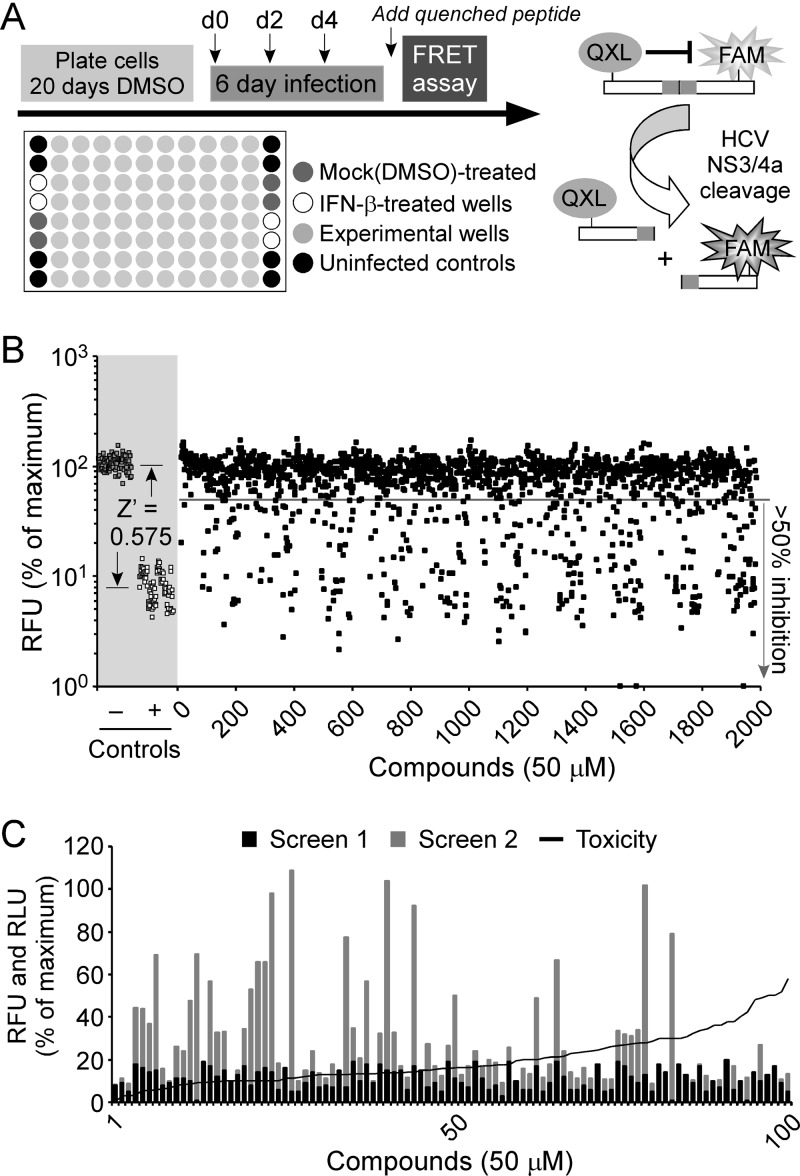

We have previously shown viral NS3 protease activity to be an accurate readout for HCVcc infection in Huh7 human hepatoma cells using a sensitive FRET-based assay (81). Using this FRET-based HCV infection assay, we evaluated the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Diversity Set II library, composed of 1,974 compounds representing a unique array of pharmacophores, for activity against HCVcc in vitro. This library represents a select group of compounds derived from a larger, 140,000-compound library. Using the Chem-X program (Oxford Molecular Group), which uses defined centers (hydrogen bond acceptor, hydrogen bond donor, positive charge, aromatic, hydrophobic, acid, and base) and defined distance intervals, a particular finite set of 1,974 compounds was obtained. Initial screening of each of these compounds was performed at a single dose of 50 μM in singlet across 24 96-well plates as illustrated in Fig. 1A. As a positive control and to confirm that an adequate Z′ was achieved throughout the screen, we included wells on each plate treated with 100 U/ml of IFN-β, a known inhibitor of HCV infection. As shown in Fig. 1B (shaded area), a Z′ factor of 0.574 was determined for the assay (distance between the standard deviations for the mock-treated samples and the IFN-β-treated samples), indicating an acceptable signal-to-noise window. On days 2, 4, and 6 postinfection, culture medium was collected to assay for toxicity using an AK release cellular membrane integrity assay, and on day 6 p.i., cell lysates were assayed for HCV NS3 protease activity as a readout for HCV infection levels. After eliminating those compounds that were toxic, we identified 99 compounds which reduced HCV infection by ≥80%. To limit the number of candidate compounds and reconfirm the results of our initial screen, we performed a secondary FRET and toxicity screen with these 99 compounds. Through this secondary screen we identified 30 molecules which reproducibly reduced HCV infection by >80%, compared to mock (DMSO)-treated control wells. The remaining compounds either were cytotoxic or did not inhibit HCV by the absolute 80% cutoff level in the secondary screen and therefore were not further evaluated.

Fig 1.

Primary and secondary compound screen. (A) Experimental design. (B) Primary screen. DMSO-Huh7 cells were infected with HCV at 0.05 FFU/cell and treated with diluent alone, IFN-β (100 U/ml), or NSC compounds (50 μM). Compounds were added at 0, 2, and 4 days p.i. At day 6 p.i., cultures were assayed for NS3 protein levels by FRET. RFU values were blank and background corrected, and data are presented as a percentage of the maximum RFU values determined in diluent-treated HCVcc-infected cultures (100% maximum infectivity). The Z′ equation was used to measure the distance between the standard deviations for the positive (diluent-treated) and negative (IFN-β-treated) controls of the assay. (C) Secondary screen. DMSO-Huh7 cells were infected with HCV at 0.05 FFU/cell and treated with diluent alone or with the top 100 active NSC compounds (50 μM) identified in the primary screen. Compounds were added at 0, 2, and 4 days p.i. At day 6 p.i., culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for cytotoxicity, and cultures were lysed and assayed for NS3 protein levels by FRET. Corrected FRET RFU values from both the primary (black bars) and secondary (gray bars) screens are presented as a percentage of RFU values determined in diluent-treated HCVcc-infected cultures (100% maximum infectivity). Relative light unit values determined from the cytotoxicity screen were blank corrected and are presented as a percentage of RLU values determined in Triton X-100-treated samples (100% maximum cytotoxicity). Samples with RLU values of >25% were considered cytotoxic.

Having confirmed a manageable set of potential anti-HCV compounds, we next determined their in vitro therapeutic indices (50% cytotoxic concentration [CC50]/50% effective concentration [EC50]). Each of the 30 compounds that reproducibly reduced HCV infection in the secondary screen were further tested in a series of dose-response assays using the same experimental design illustrated in Fig. 1A but at concentrations ranging from 0.0005 to 50 μM. On days 2, 4, and 6 p.i., culture medium was harvested to measure cytotoxicity, and at day 6 p.i., cell monolayers were lysed to measure intracellular HCV RNA levels by RT-qPCR analysis. Antiviral potency (EC50) and cytotoxicity (CC50) were interpolated from dose-response curves (using Graph Pad Prism 5) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The EC50, CC50, and corresponding therapeutic index values for the top 18 compounds are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Compound screen hits

| NSC compound no. | HCV infection (% of maximum)a |

EC50 (μM)b | CC50 (μM)b | Therapeutic index (CC50/EC50) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ||||

| 5159 | 8.59 | 1.43 | 1.4 | 25 | 18 |

| 13726 | 6.43 | 3.19 | 3.6 | >50 | >14 |

| 13728 | 12.21 | 3.96 | 0.4 | >50 | >125 |

| 24479 | 9.94 | 3.51 | 3.0 | >50 | >17 |

| 26382 | 11.93 | 3.52 | 4.2 | >50 | >12 |

| 44480 | 11.25 | 5.00 | 33.0 | >50 | >1.5 |

| 48881 | 7.83 | 3.32 | 1.8 | 25 | 14 |

| 78206 | 12.27 | 4.82 | 6.3 | >50 | >8 |

| 92896 | 10.26 | 4.04 | 2.6 | 25 | 11 |

| 109128 | 13.98 | 3.58 | 2.1 | 25 | >24 |

| 119886 | 11.62 | 3.97 | 13.2 | >50 | >4 |

| 136476 | 8.99 | 2.63 | 1.5 | >50 | 33 |

| 143101 | 9.73 | 1.62 | 9.2 | ∼50 | >5 |

| 169466 | 10.73 | 4.24 | 6.9 | >50 | >7 |

| 169959 | 14.96 | 7.23 | 18.9 | >50 | >3 |

| 308848 | 11.97 | 7.16 | 16.4 | >50 | >3 |

| 311153 | 14.91 | 6.95 | 2.5 | 50 | 20 |

| 661755 | 10.93 | 3.64 | 8 | 50 | >6 |

FRET RFU values from wells treated with the indicated compounds (50 μM) were background corrected and are expressed as a percentage of the maximum background-corrected FRET RFU values determined in diluent-treated HCVcc-infected wells (100% maximum activity). Values are for two screens each performed in singlet.

EC50 and CC50 values were calculated by assessing the antiviral activity (determined by RT-qPCR analysis) or cytotoxicity, respectively, of serial dilutions of the indicated compounds at concentrations ranging first from 50 μM to 1 μM and then from 25 μM to 0.1 μM.

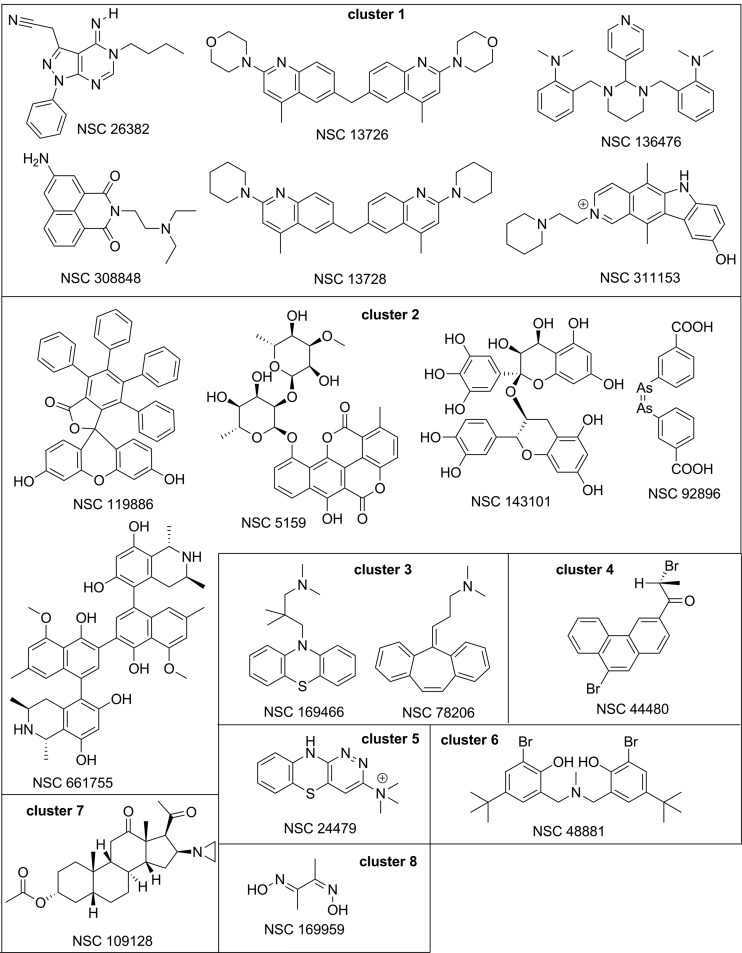

To facilitate further structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis and identify structural features that may be responsible for the similar type of activities, the compounds were clustered using BIT-MACCS fingerprints, and the resulting clusters are shown in Fig. 2. Of the eight clusters identified, cluster 1 (c1) and cluster 2 consist of six and five compounds, respectively, cluster 3 contains two compounds, and clusters 4 to 8 consist of only one compound. We had to set the bar for the similarity and overlap thresholds relatively low, at 65%, because the tested NCI Diversity Set II library was designed to contain dissimilar compounds. Even in this case, the clustering analysis performed acceptably well by grouping various nitrogen-containing polycyclic compounds in cluster 1, mostly polyphenolic type of compounds (with the exception of NSC 92896) in cluster 2, and two tricyclic compounds in cluster 3 and creating individual clusters for the rest of the compounds. We additionally assessed the similarity and dissimilarity that may be useful in the SAR interpretation.

Fig 2.

Chemical structures of candidate NSC compounds selected for mechanism-of-action analyses. Compounds are grouped by clusters 1 through 8.

In the nitrogen-containing cluster 1, two compounds, NSC 13726 and NSC 13728, are clearly close analogs, whereas other compounds appear to have rather distinctive scaffolds. NSC 26382 has a purine-like structure with little similarity to other compounds in cluster 1 or the other clusters. NSC 308848 has a tricyclic scaffold of napthalimide not found in the other 17 compounds, but it is somewhat similar to the other compounds in cluster 1 as well as to the tricyclic compounds in clusters 3 to 5. NSC 136476 contains five basic nitrogen atoms and a scaffold with four rings connected through single-bond linkers bearing some similarity with other compounds mentioned above. NSC 311153 is a substituted pyridocarbazole, with its similarity to the other compounds in this cluster being that it contains several basic nitrogen atoms. Due to its planarity, it may potentially be a DNA intercalator. Four compounds in cluster 2, NSC 5159, NSC 143101, NSC 661755, and NSC 119886, contain multiple phenolic groups, ether bonds, and polycyclic structures of comparable complexity but are otherwise different and do not contain common substructures. In cluster 3, compounds NSC 169466 and NSC 78206 are both based on tricyclic scaffolds known to be common for the atypical antipsychotics. The cluster 4 compound NSC 44480 is a substituted phenanthrene, another potential DNA intercalator. NSC 24479 from cluster 5 contains a fused ring system very similar to the phenothiazine scaffold of NSC 169466 in cluster 3. NSC 109128 in cluster 7 contains a steroid scaffold not found in the other 18 hits. Finally, cluster 8 NSC 169959 and NSC 92896 (c2) contain reactive/toxic diarsenic and general metal-complexing dioxime moieties, respectively. From a chemistry perspective, both these compounds are probably the least interesting out of the 18 hits, as their mechanism of action is unlikely to be worth pursuing.

Information regarding each of the 1,974 compounds in the NIH/NCI diversity set library can be found online (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/dscb/diversity_explanation.html). Table S1 in the supplemental material provides additional information specific for each of the 18 compounds detailed in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Notably, three of the compounds have already been shown to have activity against other unrelated viruses, such as influenza A virus (NSC 143101), HIV-1 (NSC 661755), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (NSC 308848), and Marburg virus (NSC 308848). For EBV and Marburg virus, NSC 308848 (c1) inhibited viral entry, while NSC 143101 and NSC 661755, which grouped in cluster 2, inhibited influenza A virus and HIV at the level of viral replication. NSC 5159 (c2) also has anti-HCV potential as it has been shown to be an inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation, a process that is critical for HCV E1 and E2 processing (28, 32), and has in fact been proposed as a potential antiviral target (14, 18). Also notable is the tricyclic compound NSC 78206 (c3), as tricyclics or their active metabolites are believed to exert their biological actions, in part, via modulation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and TLR2 signaling (36). Likewise, HCV infection correlates with TLR expression and signaling (33, 50, 76).

Because this available information collectively highlighted that each of the 18 compounds identified could potentially affect HCV at distinct and multiple steps during infection, we proceeded to determine the steps inhibited by each of the candidate compounds. Specifically, we assessed their ability to inhibit (i) viral entry using the HCVpp system, (ii) replication by examining their ability to inhibit HCV subgenomic replicons of genotypes 1a, 1b, and 2a, and (iii) maturation and egress by testing each compound's potential to interfere with secretion of infectious HCVcc virions.

Screening for inhibitors of HCV entry using HCV pseudoparticles.

Although HCV pseudoparticles resemble HCV only at the level of surface glycoprotein expression, their ability to mimic HCV binding, internalization, and viral glycoprotein-mediated fusion has helped dissect many of the steps of HCV entry and identify numerous HCV entry factors (reviewed in reference 73). As such, they represent a convenient tool to study HCV entry (7, 23) and inhibitors of this process. To initially assess whether candidate compounds affect HCV entry, Huh7 cells were pretreated with each compound at a concentration of 25 μM (∼ 2× the 90% inhibitory concentration [IC90]) for 1.5 h and subsequently infected with pseudotyped lentiviruses encoding a luciferase reporter and bearing the glycoproteins E1 and E2 of HCV genotype 2a (JFHpp) or the VSV G glycoprotein (VSVGpp). At 72 h p.i., pseudoparticle entry was assessed by luciferase activity as previously described (61). As a positive control for inhibition of HCV entry, parallel cultures were also treated with an antibody against CD81, a known HCV entry factor (56). As expected, antibody-mediated blocking of CD81 reduced JFHpp entry by 74%. Surprisingly, of the 18 compounds tested, 50% (n = 9) inhibited JFHpp entry by ≥60% compared to control-treated cultures (Fig. 3A). Of these nine compounds, eight proved to exhibit HCV-specific inhibition, while one (NSC 24479) also appeared to significantly reduce VSVGpp in subsequent dosing assays and to directly inhibit luciferase activity (data not shown). Lastly, we determined the EC50s and CC50s of the compounds on JFHpp entry by determining the inhibitory activities and cytotoxicities of serial dilutions of the compounds at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 50 μM (Table 2).

Fig 3.

Screening for HCV entry inhibitors. (A) DMSO-Huh7 cells were pretreated with diluent, anti-CD81 antibody (36 μg/ml), or the indicated NSC compounds (25 μM) for 1.5 h prior to infection with equal amounts of JFHpp or VSVGpp. Relative light units (RLU) were determined at 72 h p.i. and blank corrected and are graphed as the average percentage of entry achieved in three separate experiments ± standard deviation (SD) for JFHpp (green bars) and VSVGpp (blue bars) in antibody-treated or compound-treated cultures compared to diluent-treated control cultures (100% maximum entry). (B to D) The dose-response inhibition of HCVpp genotype 2a (JFHpp), 1a (H77pp), or 1b (Con1pp) was determined for the indicated NSC compounds. DMSO-Huh7 cells were pretreated with diluent or NSC 119886 (B), NSC 143101 (C), or NSC 311152 (D) at concentrations ranging from 50 μM to 0.1 μM for 1.5 h prior to infection with equal amounts of HCVpp (genotype 2a [JFHpp], 1a [H77pp], or 1b [Con1pp]) or VSVGpp. HCVpp entry RLU determined at 72 h p.i. relative to diluent-treated cells was calculated by subtracting background and mock-control RLU values and then normalizing for VSVGpp luciferase activity. Results are graphed as a percentage of entry achieved in two separate experiments ± SD in compound-treated cultures compared to diluent-treated control cultures (100% maximum HCVpp entry).

Table 2.

HCVpp entry inhibitorsa

| NSC no. (cluster) | EC50b (μM) |

CC50b (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JFHpp | H77pp | Con1pp | ||

| 311153 (c1) | 0.7 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 50 |

| 26382 (c1) | 0.9 | —c | — | >50 |

| 119886 (c2) | 2.7 | 12.1 | 12.7 | >50 |

| 143101 (c2) | 11.2 | 22.8 | 24.3 | >50 |

| 78206 (c3) | 9.2 | — | — | >50 |

| 169466 (c3) | 2.2 | — | — | >50 |

| 109128 (c3) | 2.2 | — | — | >50 |

| 48881 (c6) | 3.4 | — | — | >50 |

All 18 compounds were tested, but only compounds that scored positive are shown.

EC50 and CC50 values were calculated by assessing the antiviral activity (determined by lentivirus pseudoparticle Luc activity analysis) or cytotoxicity, respectively, of serial dilutions of indicated compounds at concentrations ranging from 50 μM to 0.1 μM.

—, <75% reduction.

Since HCV genotype 1 is the predominant genotype found in North America and Europe, we additionally tested these 8 active JFHpp entry inhibitors against pseudotyped lentiviruses bearing the glycoproteins E1 and E2 of HCV genotype 1a (H77pp) and 1b (Con1pp). Only three of the eight compounds (NSC 119886, NSC 143101, and NSC 311153) showed cross genotypic activity and inhibited H77pp, Con1pp, and JFHpp in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B to D and Table 2).

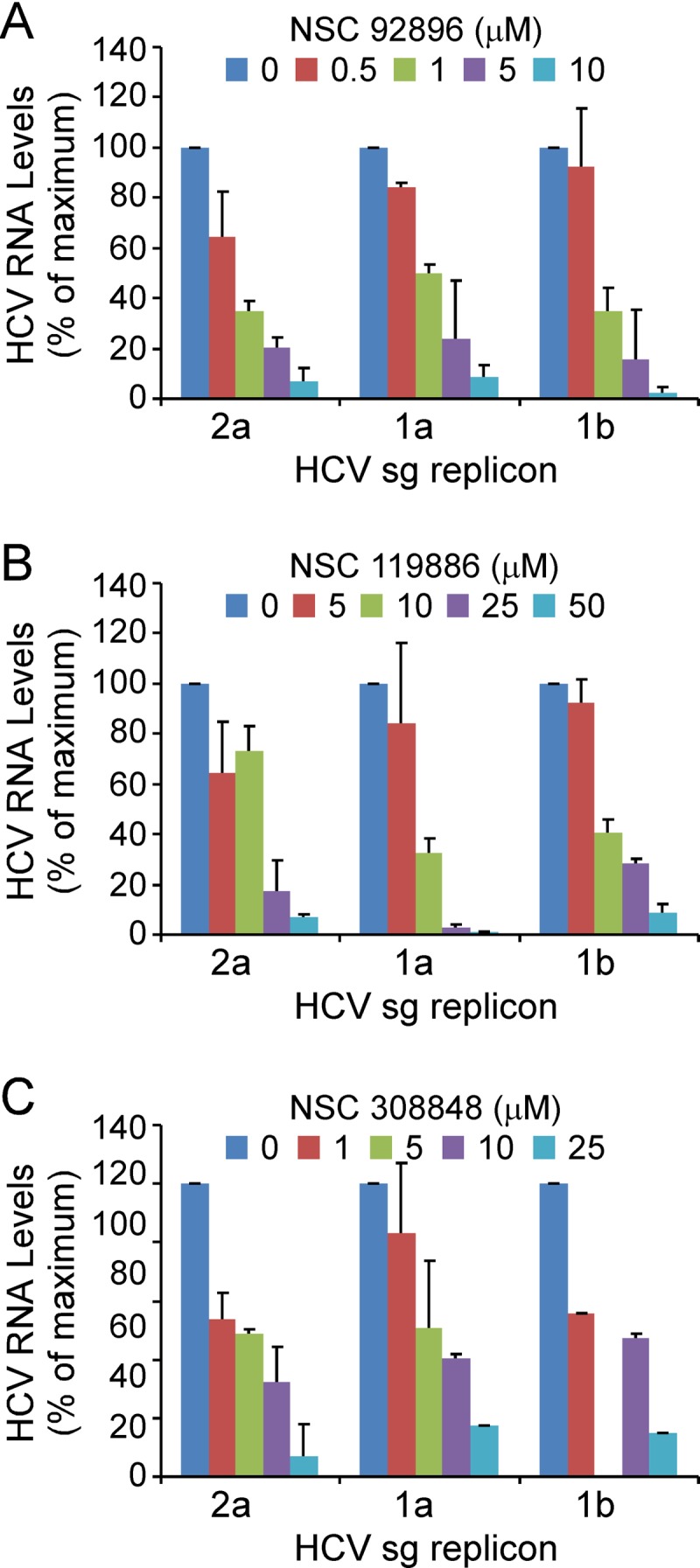

Screening for inhibitors of HCV RNA replication using HCV subgenomic replicons.

Since the original report by Lohmann et al. in 1999 (48), subgenomic replicons of multiple genotypes and HCV clones as well as replication-competent full-length replicons have been developed (9, 10, 37, 39, 75). These surrogate systems have proven invaluable for the study of HCV protein translation, RNA replication, and replication complex formation and stability (65). To assess whether candidate compounds affect HCV RNA replication, independent of entry and assembly, Huh7 cells harboring subgenomic HCV replicons of genotypes 1a, 1b, and 2a were treated for 6 days with each of the 18 candidate NSC compound at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 50 μM. Total RNA was subsequently harvested, and HCV RNA copies/μg total RNA were quantified by RT-qPCR. EC50s as well as cytoxicities (CC50s) were determined for each compound in each subgenomic replicon cell line (Table 3). In total, seven compounds which exhibited dose-responsive inhibition of JFH-1 sg2a RNA replication were identified. Consistent with this, six of these compounds also inhibited, at comparable doses, steady-state full-length JFH-1 HCVcc RNA levels in chronically infected Huh7 cells (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), further confirming the postentry inhibitory activity of those compounds. Of the seven compounds that were effective inhibitors of sg2a HCV RNA replication, two compounds (NSC 26382 and NSC 44480) also inhibited sg1a RNA replication, while three compounds (NSC 92896-c2, NSC 119886-c2, and NSC 308848-c1) were effective at inhibiting all three of the subgenomic replicon genotypes tested (Table 3 and Fig. 4).

Table 3.

HCV subgenomic replicon inhibitorsa

| NSC no. (cluster) | EC50b (μM) |

CC50b (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sg2a | sg1a | sg1b | ||

| 308848 (c1) | 3.9 | 5.6 | 10.3 | >50 |

| 26382 (c1) | 7.3 | 10.1 | —c | >50 |

| 13726 (c1) | 5.5 | — | — | >50 |

| 13728 (c1) | 5.4 | — | — | >50 |

| 119886 (c2) | 21.1 | 6.9 | 4.7 | >50 |

| 92896 (c2) | 0.5 | 1.9 | 0.7 | >50 |

| 5159 (c2) | — | 1.4 | — | 25 |

| 109128 (c7) | — | 14.15 | — | >50 |

| 44481 (c6) | 12.2 | 9.9 | — | >50 |

| 169959 (c8) | — | — | 3.82 | 25 |

All 18 compounds were tested, but only compounds that scored positive are shown.

EC50 and CC50 values were calculated by assessing the antiviral activity (determined by RT-qPCR analysis) or cytotoxicity, respectively, of serial dilutions of indicated compounds at concentrations ranging from 50 μM to 0.1 μM.

—, <75% reduction.

Fig 4.

Screening of HCV RNA replication inhibitors. Huh7 cells harboring subgenomic replicons of genotype 2a, 1a, or 1b were treated with NSC 92896 (A), NSC 119886 (B), or NSC 308848 (C) at concentrations ranging from 50 μM to 0.1 μM for 6 days. Following treatment, intracellular RNA was isolated, HCV RNA levels were determined by RT-qPCR, and data were normalized to GAPDH. Results are graphed as the average percentage of HCV RNA copies/μg of total RNA in compound-treated cultures compared to diluent-treated (0 μM) cultures in two separate experiments ± SD.

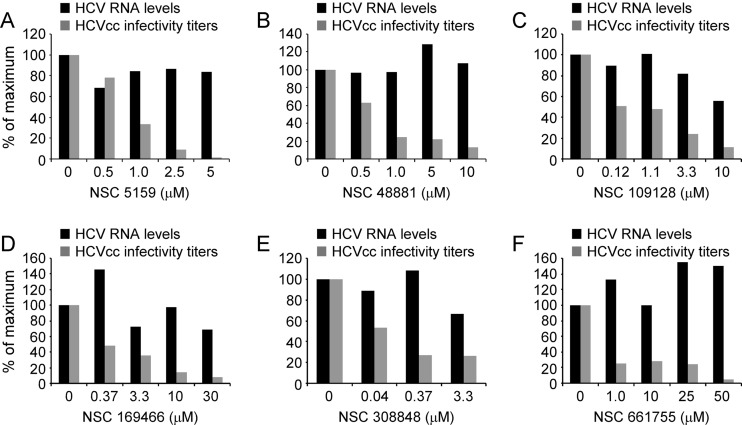

Screening for inhibitors of HCV egress using chronically HCVcc-infected cultures.

HCV can efficiently establish persistent infection in nondividing DMSO-treated Huh7 cell cultures, characterized by steady-state viral RNA replication, de novo virion production, and constitutive secretion of infectious HCVcc (62). Utilizing this system to assess the effects of our candidate compounds on the secretion of infectious HCVcc independent of early infection steps such as entry and viral RNA amplification, we treated chronically HCVcc-infected nongrowing Huh7 cultures with serial dilutions of our 18 candidate NSC compounds at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 50 μM for 6 consecutive days and subsequently quantified infectious HCVcc virions in the supernatants of treated cultures. To identify those compounds that were active only at a step after replication (e.g., maturation, morphogenesis, or egress), we additionally measured intracellular HCV RNA levels by RT-qPCR analysis and disregarded those compounds that reduced viral RNA replication and HCVcc infectivity titers to a similar extent. Of the 18 candidate compounds tested, eight NSC compounds markedly reduced extracellular HCV titers while having no marked inhibitory effect on HCV RNA replication at the assayed concentrations (Table 4 and Fig. 5). Of these eight compounds, five showed anti-HCV activity at low-μM concentrations, with NSC 169466 and NSC 308848 reducing HCV infectivity titers by ≥50% at nM concentrations (Fig. 5D and E and Table 4).

Table 4.

HCVcc egress inhibitorsa

| NSC no. (cluster) | EC50b (μM) | CC50b (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| 308848 (c1) | 0.04 | >50 |

| 311153 (c1) | 0.12 | >50 |

| 5159 (c2) | 0.8 | 25 |

| 119886 (c2) | 5 | >50 |

| 661755 (c2) | 0.08 | 50 |

| 169466 (c3) | 0.37 | >50 |

| 48880 (c4) | 0.76 | >50 |

| 109128 (c7) | 1.1 | >50 |

All 18 compounds were tested, but only compounds that scored positive are shown.

EC50 and CC50 values were calculated by assessing the reduction in HCVcc infectivity titers or cytotoxicity, respectively, of serial dilutions of indicated compounds at concentrations ranging from 50 μM to 0.01 μM.

Fig 5.

Screening of HCVcc egress inhibitors. DMSO-Huh7 cells chronically infected with HCVcc were treated with indicated NSC compounds at concentrations ranging from 50 μM to 0.1 μM for 6 days. Following treatment, HCVcc-containing supernatant was collected and HCVcc infectivity titers were determined by limiting dilution analysis of HCV focus formation on naïve Huh7 cells. RNA was also extracted for quantification of intracellular RNA levels by RT-qPCR. Results are graphed as a percentage of GAPDH-normalized HCV RNA copies/μg of total RNA (black bars) or HCVcc infectivity titers (FFU/ml) (gray bars) determined in compound-treated cultures compared to diluent-treated (0 μM) cultures.

DISCUSSION

Using a cell-based FRET HCV infection assay, which we have previously shown to be amendable to HTS (81), we identified 18 compounds from the NIH/NCI Diversity Set II library with reproducible, dose-responsive anti-HCV activity in vitro. All these compounds inhibited HCV infection at noncytotoxic concentrations (CC50/EC50) (Table 1). Although a total of 18 hits is higher than expected from a library of this size, this may be because the NCI Diversity Set II library is not derived from random synthesis of compound derivatives, but rather each compound has undergone previous selection from a larger, 140,000-compound library. Importantly, in order to confirm HCV antiviral activity and determine what aspect of infection was inhibited by these 18 NSC compounds, we performed systematic analyses using multiple assays and model systems, including HCV entry (HCVpp), replication (HCV subgenomic replicons), and egress (chronic HCVcc). The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 5 and discussed below.

Table 5.

Summary of NSC candidate compounds

| NSC compound no. | Mechanism of action | Genotype specificity | Therapeutic index (CC50/EC50) | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26382 | Entry inhibitor | 2a | >55 | c1 |

| Replication inhibitor | 2a, 1a | >6, >5 | ||

| 13726 | Replication inhibitor | 2a | >9 | c1 |

| 13728 | Replication inhibitor | 2a | >9 | c1 |

| 308848 | Replication inhibitor | 2a, 1a, 1b 2a | >12, >9, >5 | c1 |

| Egress inhibitor | >1250 | |||

| 311153 | Entry inhibitor | 2a, 1a, 1b | >71, >7, >7 | c1 |

| Egress inhibitor | 2a | >416 | ||

| 136476 | Unknown | c1 | ||

| 143101 | Entry inhibitor | 2a, 1a, 1b | >9, >2, >2 | c2 |

| 119886 | Entry inhibitor | 2a, 1a, 1b | >19, >4, >4 | c2 |

| Replication inhibitor | 2a, 1a, 1b 2a | >2, >7, >10 | ||

| Egress inhibitor | >10 | |||

| 92896 | Replication inhibitor | 2a, 1a, 1b | >100, >26, >71 | c2 |

| 5159 | Replication inhibitor | 1a | 17.9 | c2 |

| Egress inhibitor | 2a | 32 | ||

| 661755 | Egress inhibitor | 2a | 625 | c2 |

| 78206 | Entry inhibitor | 2a | >5 | c3 |

| 169466 | Entry inhibitor | 2a | >22 | c3 |

| Egress inhibitor | 2a | >135 | ||

| 44480 | Replication inhibitor | 2a, 1a | >4, >5 | c4 |

| 48881 | Entry inhibitor | 2a | >14 | c6 |

| Egress inhibitor | 2a | >65 | ||

| 109128 | Entry inhibitor | 2a | >22 | c7 |

| Replication inhibitor | 1a | >3 | ||

| Egress inhibitor | 2a | >45 | ||

| 169959 | Replication inhibitor | 1b | 6.5 | c8 |

Entry.

Using the HCVpp system, which mimics HCV entry at the level of E1/E2-dependent binding, endocytosis, and fusion, we identified eight NSC compounds that inhibited entry of genotype 2a JFHpp, three of which effectively inhibited entry of all three HCVpp genotypes (Table 2). The apparent JFHpp preference is not surprising, since the initial primary screen was performed with the genotype 2a JFH-1 HCVcc clone and the intergenotypic differences observed using the HCVpp system are likely due to differences between the E1/E2 protein sequences of genotype 2a and genotypes 1a and 1b, which share only 40 to 60% amino acid homology. Whether this reflects differences in the entry requirements (i.e., mechanisms of entry) across these three genotypes (2a, 1a, and 1b) is not known.

Replication.

To assess HCV polyprotein processing and RNA replication in the absence of viral entry and egress, we utilized the HCV subgenomic replicon system, which has been widely and successfully used to identify inhibitors that target HCV replication, such as NS3/4a protease and NS5B polymerase inhibitors (70). Using HCV subgenomic replicons of genotypes 1a (H77), 1b (Con1), and 2a (JFH-1), we identified 10 compounds that inhibited sgRNA replication of at least one genotype in a dose-dependent manner, with EC50s ranging between 1 and 21 μM (Table 3). Curiously, unlike the obvious selective inhibition of the JFH-1 clone seen among the entry inhibitors (Table 2), we did not observe a strong preference for inhibition of the sgJFH replicon at the level of HCV RNA replication. Of the 10 compounds identified, three were effective against all three genotypes (NSC 92896, NSC 119886, and NSC 308848). However, two compounds showed preferential inhibition for both genotypes 1a and 2a (NSC 26382 and NSC 44480), while three inhibitors were non-2a genotype specific at the level of replication (1a, NSC 5159 and NSC 109128; 1b, NSC 169959). In general, fewer compounds with inhibitory activity against sg1b RNA replication were identified, and we speculate that this may be due to the fact that the sg1a and sg2a replicons were established using the same Huh7 laboratory cell line, while the sg1b replicon cells were previously established using a distinct Huh7 laboratory line (9). Thus, within the list of compounds designated replication inhibitors (Table 5), we hypothesize that some compounds may act by targeting specific cellular proteins that are either (i) essential for a specific HCV genotype or (ii) present at different levels within the Huh7 laboratory cell lines.

Egress.

Since the development of the HCVcc infectious cell culture system, we can now study and dissect late stages of HCV infection, such as assembly, maturation, and egress. These late steps of viral infection represent many potential opportunities for antiviral intervention; however, to date, inhibitors of HCV egress are not clinically available. Notably, we found that 8 of the candidate compounds inhibited HCVcc egress from chronically HCVcc-infected Huh7 cultures in a dose-dependent manner (Table 4). These compounds had no effect on HCV RNA replication at the assayed concentrations, demonstrating that their ability to reduce HCVcc infectivity titers was not an indirect effect of reduced HCV RNA replication (Fig. 5). Consistent with a primary inhibition of a postreplication event, we noted that when secretion of infectious virus was specifically measured, the resulting potency calculations (EC50s) were generally higher for this group of compounds than those calculated during the initial screens, when high levels of intracellular HCV replication were able to mask the extent to which infectious progeny virions were secreted (Table 4 versus Table 1). For example, we initially calculated a therapeutic index of 20 for NSC 311153 when used to inhibit HCVcc during acute infection, which encompasses all steps of infection; however, when only HCV egress was assessed, its therapeutic index increased to >416 (Table 5).

Analysis of candidate inhibitors.

From the information available on the NSC compounds via the NCI/DPT database and in the literature, only 3 of the 18 candidate NSC compounds were found to have previous reported antiviral activity (against influenza A virus [NSC 143101-c2], HIV-1 [NSC 661755-c2], EBV [NSC 308848-c1], and Marburg virus [NSC 308848-c1]). Of the remaining 15 NSC compounds, most have been reported to exhibit various cell-based biological activities, which in most cases do not obviously relate to the antiviral effects observed in our assays (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

(i) NSC 143101.

NSC 143101 (c2) and NSC 119886 (c2) inhibited entry of all three HCVpp genotypes, with no evidence of toxicity (Tables 2 and 5). NSC 143101, in particular, is structurally similar to proanthocyanidins (oligomeric proanthocyanidins or condensed tannins), a subgroup of the flavonoid class of polyphenols. Relevant to viral entry, proanthocyanidins have been shown to inhibit entry of herpes simplex virus (25, 26) and HIV-1 (22, 54). Although no published studies have evaluated the antiviral effect of proanthocyanidins on HCV entry, numerous studies have demonstrated that some flavonoids can inhibit HCV replication and HCVpp entry (3, 44, 68, 74). For example, a recent study by Calland et al. showed that (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a flavonoid present in green tea extract and belonging to the subclass of catechins, inhibits HCV infectivity by more than 90% at an early step of infection, most likely at the level of entry (12). Thus, due to the structural similarities between certain flavonoids and NSC 143101, we hypothesize that this compound may function via a similar mechanism(s) to inhibit HCV cell entry.

(ii) NSC 661755.

NSC 661755 (cluster 2), also known as Michellamine B, is a naturally occurring alkaloid found in the Central African tropical plant Ancistrocladus korupensis. It has antioxidation properties (78) and inhibitory activity against the arachidonic acid-metabolizing lipoxygenase (hLO) enzymes (17), which catalyze the dioxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids to their hydroperoxy acids (66). Michellamine B has also been shown to inhibit HIV reverse transcriptase and virus-mediated cellular fusion (77) as well as HIV-induced cell killing in a variety of human cell lines (11, 51, 52). Here we show that NSC 661755 reduced infectious HCVcc production in persistently infected cells (Table 4) without affecting intracellular RNA levels (Table 3; Fig. 5), indicating that this compound targets an aspect of the HCV infection downstream of viral replication, such as particle assembly, maturation, morphogenesis, or egress. Since fatty acids, cholesterol, and lipoprotein synthesis play a critical role in the late steps of HCV infection (6), it is plausible to speculate that NSC 661755 alteration of the fatty acid-metabolizing enzyme 12-hLO (17) may be linked to its effect on HCVcc virion production. Importantly, this compound is currently being investigated as an anti-HIV and anticancer agent; hence, its potential utility as an anti-HCV agent could also be considered.

(iii) NSC 5159.

NSC 5159, another cluster 2 compound, is an anthracycline-related bis-lactone chartreusin isolated from Streptomyces sp. strain QD518. This compound has been well characterized as an antibiotic and as an anticancer agent (58). Specifically, it has been shown to inhibit negatively the superhelical DNA relaxation catalyzed by prokaryotic topoisomerase I and conversion of the superhelical DNA into a unit-length linear form catalyzed by single-strand-specific S1 nuclease (72). Interestingly, a recent study Kirubakaran et al. demonstrated via in silico analyses that chartreusin may have a high binding affinity for the tyrosine kinase receptors EphA2, EGFR, and EGFRvIII (40). Although these cellular receptors have also been implicated in HCV entry (49), treatment of Huh7 cells with NSC 5159 did not affect HCVpp entry. Rather, we classified NSC 5159 as an inhibitor of JFH-1 HCVcc egress (Fig. 5). Interestingly, NSC 5159 has also been reported to be active in an HTS identifying inhibitors of N-linked glycosylation (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assay/assay.cgi?aid=588692#aAddition). Since N-linked glycosylation is critical for HCV E1 and E2 processing (28) and necessary for glycoprotein incorporation into infectious virions (32), we speculate that NSC 5159 may affects HCV egress via inhibition of this cellular pathway.

(iv) NSC 308848.

NSC 308848 (cluster 1), one of the compounds previously shown to inhibit entry of EBV and Marburg virus, likewise reduced JFHpp, H77pp, and Con1pp entry (data not shown); however, it was also active against VSVGpp, and it was therefore not further considered as a specific inhibitor of HCV entry. While NSC 308848 may very well represent a fairly nonspecific inhibitor of viral entry, it was also effective at reducing subgenomic (Table 3) and full-length (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) RNA replication of all three HCV genotypes tested. Thus, its mechanism of action at the level of inhibiting HCV RNA replication warrants further investigation.

(v) NSC 13726 and NSC13728.

NSC 13726 and NSC13728 (cluster 1) reduced intracellular HCV RNA levels in sg2a replicon cells (Table 3) and persistently HCVcc-infected cells (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Both compounds contain two quinoline rings connected through a methylene group and differ only by the substituents in the quinoline ring. Quinoline-containing compounds have been shown to have various biological functions ranging from antimalarial and antimicrobial activities to anticancer functions. In addition, they have been extensively examined for their role in the inhibition of tyrosine kinases, the proteasome, tubulin polymerization, and DNA repair (reviewed in reference 67). Relevant to viral inhibition, compounds containing quinoline moieties have also been shown to have activity against numerous viruses, such as bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) and HCV at the level of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (13) and hepatitis B virus by acting as nonnucleoside anti-HBV agents (31). However, both NSC 13726 and 13728 are structurally dissimilar to the compounds used in the aforementioned studies; therefore, whether their anti-HCV modes of action are mechanistically similar remains to be determined.

(vi) NSC 78206.

NSC 78206 (cluster 3), also known as cyclobenzaprine, is a muscle relaxant used to relieve skeletal muscle spasms in acute musculoskeletal conditions (64). NSC 78206 is a tricyclic analog compound, which may be relevant because tricyclics and their active metabolites have been shown to have various biological functions, such as modulation of TLR4 and TLR2 signaling (36), whose expression and signaling are known to affect HCV (33, 50, 76) and inhibition of the drug-metabolizing enzyme aldehyde oxidase (55). In this study, we found that NSC 78206 inhibited JFHpp entry (Fig. 2A and Table 2) and marginally reduced the release of infectious HCV virions from chronically HCVcc-infected cells (data not shown). One could speculate that this compound's putative effect on late stages of the HCV infection could be mediated by modulation of TLR signaling.

(vii) NSC 119886.

We identified one compound, NSC 119886 (c3), that inhibited all HCV genotypes at all steps of infection that were evaluated (entry, replication, and egress). Structurally, NSC 119886 is a tetraphenylspiro-containing compound. Apart from its chemical properties, no information regarding this compound is currently available, and therefore its putative mechanism of action could not be determined.

(viii) NSC 136476.

Curiously, one compound, NSC 136476 (c1), inhibited HCVcc infection in our initial screen by >91% and had one of the highest therapeutic indices (i.e., 33) (Table 1) but then did not appear to inhibit any specific aspect of infection that we tested (Table 5). Our analyses suggest that NSC 136476 acts at a postentry step, most likely downstream of replication (e.g., assembly, maturation, or egress); however, no conclusive mechanism of action could be determined.

In summary, we utilized a robust and sensitive cell-based HCV FRET assay to screen 1,974 compounds from the NIH/NCI Diversity Set II library using a low-multiplicity-of-infection approach in order to identify compounds that inhibit HCV at any step of infection. This approach identified 18 NSC compounds with anti-HCV activity and diverse putative mechanisms of action, which may provide insight to facilitate the development of new HCV inhibitors. Although the use of the JFH-1-based HCVcc infection system may have skewed our assay to identify inhibitors specific to genotype 2a, 5 of the NSC compounds did exhibit broad genotypic antiviral activity (NSC 92896, NSC 119886, NSC 143101, NSC 308848, and NSC 311153), highlighting the utility of our overall approach. Further analyses on structurally similar compound derivatives are planned, not only to possibly identify more potent compounds but also to determine what aspects of these compounds are critical for their antiviral activity. Meanwhile, we will use these compounds as probes to study and further dissect the biology of HCV infection, including the cellular components necessary for productive infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter Corcoran for outstanding technical assistance and the members of the Uprichard lab for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH Public Health Service grants R01-AI070827, R56/R01-AI078881, R03-AI085226, and R21-CA133266 and the University of Illinois Chicago Council To Support Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 September 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Afdhal NH. 2004. The natural history of hepatitis C. Semin. Liver Dis. 24(Suppl 2):3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. 1999. Treatment strategies for chronic hepatitis C: update since the 1997 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14(Suppl):S12–S18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmed-Belkacem A, et al. 2010. Silibinin and related compounds are direct inhibitors of hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Gastroenterology 138:1112–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alter HJ, Seeff LB. 2000. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus infection: a perspective on long-term outcome. Semin. Liver Dis. 20:17–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Armstrong GL, et al. 2006. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann. Intern. Med. 144:705–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bartenschlager R, Penin F, Lohmann V, Andre P. 2011. Assembly of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. Trends Microbiol. 19:95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. 2003. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1-E2 envelope protein complexes. J. Exp. Med. 197:633–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benedicto I, et al. 2009. The tight junction-associated protein occludin is required for a postbinding step in hepatitis C virus entry and infection. J. Virol. 83:8012–8020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blight KJ, Kolykhalov AA, Rice CM. 2000. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science 290:1972–1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blight KJ, McKeating JA, Marcotrigiano J, Rice CM. 2003. Efficient replication of hepatitis C virus genotype 1a RNAs in cell culture. J. Virol. 77:3181–3190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boyd MR, et al. 1994. Anti-HIV michellamines from Ancistrocladus korupensis. J. Med. Chem. 37:1740–1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calland N, et al. 2012. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate is a new inhibitor of hepatitis C virus entry. Hepatology 55:720–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carta A, et al. 2011. Quinoline tricyclic derivatives. Design, synthesis and evaluation of the antiviral activity of three new classes of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19:7070–7084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chapel C, et al. 2007. Reduction of the infectivity of hepatitis C virus pseudoparticles by incorporation of misfolded glycoproteins induced by glucosidase inhibitors. J. Gen. Virol. 88:1133–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chemical Computing Group Inc 2011. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2011.10 Chemical Computing Group Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada [Google Scholar]

- 16. Choi S, Sainz B, Jr, Corcoran P, Uprichard SL, Jeong H. 2009. Characterization of increased drug metabolism activity in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated Huh7 hepatoma cells. Xenobiotica 39:205–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deschamps JD, et al. 2007. Discovery of platelet-type 12-human lipoxygenase selective inhibitors by high-throughput screening of structurally diverse libraries. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 15:6900–6908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Durantel D. 2009. Celgosivir, an alpha-glucosidase I inhibitor for the potential treatment of HCV infection. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 10:860–870 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. El-Serag HB. 2002. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 36:S74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Evans MJ, et al. 2007. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature 446:801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. 2005. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature 436:967–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fink RC, Roschek B, Jr., Alberte RS. 2009. HIV type-1 entry inhibitors with a new mode of action. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 19:243–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flint M, Logvinoff C, Rice CM, McKeating JA. 2004. Characterization of infectious retroviral pseudotype particles bearing hepatitis C virus glycoproteins. J. Virol. 78:6875–6882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gastaminza P, et al. 2008. Cellular determinants of hepatitis C virus assembly, maturation, degradation, and secretion. J. Virol. 82:2120–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gescher K, Hensel A, Hafezi W, Derksen A, Kuhn J. 2011. Oligomeric proanthocyanidins from Rumex acetosa L. inhibit the attachment of herpes simplex virus type-1. Antiviral Res. 89:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gescher K, et al. 2011. Proanthocyanidin-enriched extract from Myrothamnus flabellifolia Welw. exerts antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus type 1 by inhibition of viral adsorption and penetration. J. Ethnopharmacol. 134:468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glue P, et al. 2000. Pegylated interferon-alpha2b: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and preliminary efficacy data. Hepatitis C Intervention Therapy Group. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 68:556–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goffard A, et al. 2005. Role of N-linked glycans in the functions of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins. J. Virol. 79:8400–8409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gosert R, et al. 2003. Identification of the hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex in Huh-7 cells harboring subgenomic replicons. J. Virol. 77:5487–5492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grove J, et al. 2007. Scavenger receptor BI and BII expression levels modulate hepatitis C virus infectivity. J. Virol. 81:3162–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guo RH, et al. 2011. Synthesis and biological assay of 4-aryl-6-chloro-quinoline derivatives as novel non-nucleoside anti-HBV agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19:1400–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Helle F, et al. 2010. Role of N-linked glycans in the functions of hepatitis C virus envelope proteins incorporated into infectious virions. J. Virol. 84:11905–11915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoffmann M, et al. 2009. Toll-like receptor 2 senses hepatitis C virus core protein but not infectious viral particles. J. Innate Immun. 1:446–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsu M, et al. 2003. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:7271–7276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang H, et al. 2007. Hepatitis C virus production by human hepatocytes dependent on assembly and secretion of very low-density lipoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:5848–5853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hutchinson MR, et al. 2010. Evidence that tricyclic small molecules may possess Toll-like receptor and myeloid differentiation protein 2 activity. Neuroscience 168:551–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ikeda M, Yi M, Li K, Lemon SM. 2002. Selectable subgenomic and genome-length dicistronic RNAs derived from an infectious molecular clone of the HCV-N strain of hepatitis C virus replicate efficiently in cultured Huh7 cells. J. Virol. 76:2997–3006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kapadia SB, Barth H, Baumert T, McKeating JA, Chisari FV. 2007. Initiation of hepatitis C virus infection is dependent on cholesterol and cooperativity between CD81 and scavenger receptor B type I. J. Virol. 81:374–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kato T, et al. 2003. Efficient replication of the genotype 2a hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon. Gastroenterology 125:1808–1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kirubakaran P, et al. 2011. In silico studies on marine actinomycetes as potential inhibitors for Glioblastoma multiforme. Bioinformation 6:100–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Komurian-Pradel F, et al. 2004. Strand specific quantitative real-time PCR to study replication of hepatitis C virus genome. J. Virol. Methods 116:103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Krieger N, Lohmann V, Bartenschlager R. 2001. Enhancement of hepatitis C virus RNA replication by cell culture-adaptive mutations. J. Virol. 75:4614–4624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Law M, et al. 2008. Broadly neutralizing antibodies protect against hepatitis C virus quasispecies challenge. Nat. Med. 14:25–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li S, et al. 2010. Procyanidin B1 purified from Cinnamomi cortex suppresses hepatitis C virus replication. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 20:239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lindenbach BD, et al. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309:623–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. 2005. Unravelling hepatitis C virus replication from genome to function. Nature 436:933–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu S, et al. 2009. Tight junction proteins claudin-1 and occludin control hepatitis C virus entry and are downregulated during infection to prevent superinfection. J. Virol. 83:2011–2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lohmann V, et al. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285:110–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lupberger J, et al. 2011. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nat. Med. 17:589–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Machida K, et al. 2006. Hepatitis C virus induces Toll-like receptor 4 expression, leading to enhanced production of beta interferon and interleukin-6. J. Virol. 80:866–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Manfredi KP, et al. 1991. Novel alkaloids from the tropical plant Ancistrocladus abbreviatus inhibit cell killing by HIV-1 and HIV-2. J. Med. Chem. 34:3402–3405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McMahon JB, et al. 1995. Michellamine B, a novel plant alkaloid, inhibits human immunodeficiency virus-induced cell killing by at least two distinct mechanisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:484–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nahmias Y, et al. 2008. Apolipoprotein B-dependent hepatitis C virus secretion is inhibited by the grapefruit flavonoid naringenin. Hepatology 47:1437–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nair MP, et al. 2002. Grape seed extract proanthocyanidins downregulate HIV-1 entry coreceptors, CCR2b, CCR3 and CCR5 gene expression by normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biol. Res. 35:421–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Obach RS, Huynh P, Allen MC, Beedham C. 2004. Human liver aldehyde oxidase: inhibition by 239 drugs. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 44:7–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pileri P, et al. 1998. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282:938–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ploss A, et al. 2009. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature 457:882–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Portugal J. 2003. Chartreusin, elsamicin A and related anti-cancer antibiotics. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents 3:411–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Poynard T, Yuen MF, Ratziu V, Lai CL. 2003. Viral hepatitis C. Lancet 362:2095–2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sainz B, Jr, et al. 2011. The Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor: a novel hepatitis C virus entry factor and potential therapeutic target. Nat. Med. 18:281–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sainz B, Jr, Barretto N, Uprichard SL. 2009. Hepatitis C Virus infection in phenotypically distinct Huh7 cell lines. PLoS One 4:e6561 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sainz B, Jr., Chisari FV. 2006. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus by well-differentiated, growth-arrested human hepatoma-derived cells. J. Virol. 80:10253–10257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Scarselli E, et al. 2002. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 21:5017–5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. See S, Ginzburg R. 2008. Skeletal muscle relaxants. Pharmacotherapy 28:207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sheehy P, et al. 2007. In vitro replication models for the hepatitis C virus. J. Viral Hepat. 14:2–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Solomon EI, Zhou J, Neese F, Pavel EG. 1997. New insights from spectroscopy into the structure/function relationships of lipoxygenases. Chem. Biol. 4:795–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Solomon VR, Lee H. 2011. Quinoline as a privileged scaffold in cancer drug discovery. Curr. Med. Chem. 18:1488–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Takeshita M, et al. 2009. Proanthocyanidin from blueberry leaves suppresses expression of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 284:21165–21176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tencate V, Sainz B, Jr, Cotler SJ, Uprichard SL. 2010. Potential treatment options and future research to increase hepatitis C virus treatment response rate. Hepat. Med. 2010:125–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Uprichard SL. 2010. Hepatitis C virus experimental model systems and antiviral drug research. Virol. Sin. 25:227–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Uprichard SL, Chung J, Chisari FV, Wakita T. 2006. Replication of a hepatitis C virus replicon clone in mouse cells. Virol. J. 3:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Uramoto M, et al. 1983. Specific binding of chartreusin, an antitumor antibiotic, to DNA. FEBS Lett. 153:325–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. von Hahn T, Rice CM. 2008. Hepatitis C virus entry. J. Biol. Chem. 283:3689–3693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wagoner J, et al. 2010. Multiple effects of silymarin on the hepatitis C virus lifecycle. Hepatology 51:1912–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wakita T, et al. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11:791–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wang JP, et al. 2010. Circulating Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2, TLR4, and regulatory T cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C. APMIS 118:261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. White EL, et al. 1999. Michellamine alkaloids inhibit protein kinase C. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 365:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. White EL, Ross LJ, Hobbs PD, Upender V, Dawson MI. 1999. Antioxidant activity of michellamine alkaloids. Anticancer Res. 19:1033–1035 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Williams R. 2006. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatology 44:521–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wunschmann S, Medh JD, Klinzmann D, Schmidt WN, Stapleton JT. 2000. Characterization of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HCV E2 interactions with CD81 and the low-density lipoprotein receptor. J. Virol. 74:10055–10062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yu X, Sainz B, Jr., Uprichard SL. 2009. Development of a cell-based hepatitis C virus infection fluorescent resonance energy transfer assay for high-throughput antiviral compound screening. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4311–4319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yu X, Uprichard SL. 2010. Cell-based hepatitis C virus infection fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay for antiviral compound screening. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 17:Unit 17 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zeisel MB, et al. 2007. Scavenger receptor class B type I is a key host factor for hepatitis C virus infection required for an entry step closely linked to CD81. Hepatology 46:1722–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhong J, et al. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9294–9299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.