Abstract

The twin-arginine translocase (TAT) in some bacterial pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia pseudomallei, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, contributes to pathogenesis by translocating extracellular virulence determinants across the inner membrane into the periplasm, thereby allowing access to the Xcp (type II) secretory system for further export in Gram-negative organisms, or directly to the outside surface of the cell, as in M. tuberculosis. TAT-mediated secretion appreciably contributes to virulence in both animal and plant models of bacterial infection. Consequently, TAT function is an attractive target for small-molecular-weight compounds that alone or in conjunction with extant antimicrobial agents could become novel therapeutics. The TAT-transported hemolytic phospholipase C (PlcH) of P. aeruginosa and its multiple orthologs produced by the above pathogens can be detected by an accurate and reproducible colorimetric assay using a synthetic substrate that detects phospholipase C activity. Such an assay could be an effective indicator of TAT function. Using carefully constructed recombinant strains to precisely control the expression of PlcH, we developed a high-throughput screening (HTS) assay to evaluate, in duplicate, >80,000 small-molecular-weight compounds as possible TAT inhibitors. Based on additional TAT-related functional assays, purified PlcH protein inhibition experiments, and repeat experiments of the initial screening assay, 39 compounds were selected from the 122 initial hits. Finally, to evaluate candidate inhibitors for TAT specificity, we developed a TAT titration assay that determines whether inhibition of TAT-mediated secretion can be overcome by increasing the levels of TAT expression. The compounds N-phenyl maleimide and Bay 11-7082 appear to directly affect TAT function based on this approach.

INTRODUCTION

The twin-arginine translocase (TAT) secretion system was first discovered as a Sec-independent mechanism by which proteins involved in photosynthesis are transported into the thylakoids of plant chloroplasts (10). Orthologs of plant TAT proteins were then identified in Escherichia coli and subsequently in other bacteria and archaea (58). However, no orthologs or functional analogs of TAT proteins have thus far been identified in animal cells.

The TAT system in plants translocates proteins into the thylakoid compartment of chloroplasts, whereas in bacteria and archaea, it can export proteins out of the cytoplasm and across the cytoplasmic membrane. In Gram-negative organisms (e.g., E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa), proteins secreted by the TAT system are most frequently terminally localized in the periplasm, but some (e.g., phospholipases C) can be further secreted by the Xcp (i.e., type II) system, thereby becoming extracellular (41, 65, 66). In Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Bacillus spp., Mycobacterium spp., and Streptomycetes spp.) (26, 27, 36), TAT substrates typically remain cell associated upon secretion through the cytoplasmic membrane, but at least three proteins (i.e., agarase, tyrosinase, and xylanase) of Streptomycetes spp., each with a consensus TAT signal sequence, have been shown ultimately to be extracellular (57, 68).

Remarkably, the TAT machinery in both plants and bacteria translocates protein substrates that have already been folded, and, in thylakoids and proteobacteria, the TAT apparatus fundamentally is comprised of only three components (i.e., TatABC). Moreover, for some Gram-positive bacteria, TAT-mediated translocation requires only two proteins (i.e., TatAC). Finally, many TAT secreted proteins contain cofactors (e.g., iron sulfur clusters and molybdopterin), and in some instances they may be heterodimeric, where only one of the dimers needs to have a TAT signal sequence (3–5, 44, 61).

Many initially identified TAT substrates were oxidoreductases localized to the periplasm (5), but more recently it was discovered that a potent extracellular toxin (i.e., PlcH, a phospholipase C [PLC]/sphingomyelinase) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is initially translocated via TAT through the inner membrane, into the periplasm, and then out of the cell through the type II (Xcp) secretory system (41, 64, 65). We further demonstrated that a TAT mutant of P. aeruginosa was severely attenuated in virulence in a chronic rat pulmonary infection model compared to its parent strain or a complemented TAT mutant (41). Subsequently, orthologs of TAT-secreted PlcH were identified in an increasing number of bacterial pathogens. For example, the genomes of some Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains can encode as many as four separate TAT-transported PlcH orthologs (37), while the Burkholderia pseudomallei genome encodes three (31), and Burkholderia mallei and Acinetobacter baumannii each encode two. Additionally, there is a growing number of other plant and animal bacterial pathogens where TAT has now been shown to be required for full virulence, including enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7 (48), Salmonella enterica (38), Legionella pneumophila (15), Vibrio spp. (19, 71), Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (33), Pseudomonas syringae (8), and Agrobacterium tumefaciens (16).

Based on the observations that TAT is not found in any known human or animal cells but that it is required for virulence in a considerable number of bacterial pathogens, this secretory pathway could be a worthy target for the development of novel agents to mitigate bacterial virulence in an infected host. Furthermore, some bacterial genomes, including those of M. tuberculosis, M. smegmatis, and B. pseudomallei, encode β-lactamases, which have consensus TAT signal sequences and are translocated by TAT (53, 55). Affecting the secretion through mutation of B. pseudomallei PenA TAT signal sequences (e.g., RR→RK) or deletion of the genes encoding this β-lactamase (i.e., PenA) resulted in an increased susceptibility of B. pseudomallei to β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin, carbenicillin, and imipenem), as did mutation of the corresponding TAT (i.e., TatABC) genes in this organism and in M. tuberculosis (36, 53, 55). Additionally, there are two distinct β-lactamases of P. aeruginosa that have TAT-type signal sequences (i.e., RR), which, unlike the β-lactamase encoded by the chromosomal B. pseudomallei penA gene, are encoded by genes (NCBI accession numbers GU929908.1 and JN545009.1) associated with integrons or located on plasmids in ∼20 to 25% of P. aeruginosa strains examined (14, 46). However, we have not yet had the opportunity to determine whether mutation of one of the twin Arg residues in the signal sequences of these β-lactamases affects the susceptibility of these strains to β-lactam antibiotics. Nevertheless, it is not unimaginable that small-molecular-weight compounds which selectively inhibit TAT function could be used in conjunction with β-lactam antibiotics as β-lactamase inhibitors that are currently in clinical use (e.g., amoxicillin-clavulanic acid).

The extracellular virulence factor PlcH of P. aeruginosa is thus far one of the best-characterized extracellular TAT-secreted substrates (31, 35, 41, 61, 62, 65). Its expression and secretion can be rapidly and easily detected by a synthetic phospholipase C substrate (p-nitrophenyl-phosphorylcholine [NPPC]), which appears bright yellow when it is hydrolyzed by PlcH or any of its orthologs expressed by other bacteria (31, 41, 61, 62). Accordingly, we developed an assay based on PlcH-mediated hydrolysis of NPPC for our initial high-throughput screening (HTS) for TAT inhibitors. For a second level of characterization of the lead compounds (i.e., “hits”) from our initial high-throughput screen, we examined their effects on known TAT-associated phenotypes (41, 61). However, these assays for impaired TAT function may still identify compounds that act indirectly. That is, the phenotypes observed in these assays, as well as in the initial screen, could also be affected by inhibition of cellular functions other than TAT. Consequently, it would be crucial to develop a more specific functional assay to determine whether any of the lead compounds impact TAT function directly.

There were several approaches that could have been used for such a purpose. However, currently no detailed structures of the TAT apparatus or of any of its individual proteins (i.e., TatA, -B, or -C) currently exist for molecular modeling with promising lead compounds (32, 43, 67). Additionally, although an in vitro based assay of TAT function has been described for E. coli TAT, it has not yet been used for evaluating small-molecule TAT inhibitors, and it has not yet been developed for the P. aeruginosa TAT system (70). Finally, because none of the TAT proteins (i.e., TatABC) has known enzymatic activity, it would not be possible to determine whether any of our prospective inhibitors might directly affect such an activity in vitro.

Consequently, we took an alternative approach to address this issue. That is, if an inhibitor directly affects the function of TAT, then a subsequent increase in the concentration of the TAT apparatus should diminish at least some of the inhibition. Such an outcome would strongly suggest that the test compound is likely acting on TAT directly. Alternatively, if a given concentration of an inhibitor causes the same level of inhibition, regardless of the level of TAT, then it is simply not acting directly on that target. It is worthwhile to note in this regard that it has been previously shown in E. coli that overexpression of a TAT substrate can saturate the translocase but that further overexpression of TAT relieves this saturation (70).

This report describes the results of an initial high-throughput screening for TAT inhibitors using the measurement of NPPC activity in culture supernatants of a recombinant strain of P. aeruginosa and subsequently the effects of our initial hit compounds on TAT-associated phenotypes to help reduce the number of our lead compounds to a more manageable level. Finally, we describe the development of a TAT titration assay to more accurately identify the lead compounds most likely to directly inhibit TAT function (25).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The P. aeruginosa bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. aeruginosa PAO1 is from the collection of Michael Vasil, and it was originally obtained from Bruce Holloway (Monash University, Melbourne, Australia) and has been stored at −80°C continuously (22, 23, 49).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or phenotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| PAO1 | Prototroph, chl-2 | 23 |

| PAO1 ΔtatABC | ΔtatABC ΔPA5071 | 61 |

| P. aeruginosa ADD1976 ΔplcHRN | PAO1 ΔplcHRN::Mini-D3112::lacUV5::T7polA | 6, 62 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pADD3268-plcHR | Cbr, T7pol::plcHR | 6, 62 |

| pHERD20T | araC-PBAD in pUCP30T, Cbr | 51 |

| pPATat | P. aeruginosa tatABC in pHERD20T | This study |

| pBPTat | B. pseudomallei tatABC in pHERD20T | This study |

CBr, carbenicillin resistance based on the bla gene.

Construction of PAO1 TAT clones.

Sequences coding for the contiguous tatA, tatB, and tatC genes were PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA isolated from the PAO1 strain of P. aeruginosa and cloned into a pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) vector. The upstream primer contained a BamHI site just upstream of the tatA initiation codon, which created an NcoI site used in subsequent steps. The downstream PCR primer contained sequences encoding the eight amino acids of Strep tag II (WSHPQFEK) appended to the C-terminal sequences of tatC that were modified to eliminate the stop codon. The genes were then introduced into the shuttle vector pHERD20T (51), an arabinose-inducible expression vector which is based on the Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vector pUCP20T, in two steps: (i) a 933-bp NcoI-NcoI fragment starting at the P. aeruginosa tatA initiation codon and ending within the tatC gene was introduced into the unique NcoI site of pHERD20T; (ii) a fragment from a BglII site within the tatC gene (upstream of the NcoI site) to the EcoRI site in the vector sequence of the intermediate was replaced with a 692-bp BglII-EcoRI fragment from a pCR2.1 clone containing the rest of tatC with a C-terminal Strep tag and an EcoRI site within the vector sequence. The final clone in the pHERD20T vector thus contained only P. aeruginosa sequences from the tatA initiation codon to the C terminus of tatC, appended with the Strep tag, under the control of the arabinose-inducible pBAD promoter. This plasmid DNA was then isolated from the transformed E. coli Top10 cells (Invitrogen) and used to transform a PAO1 strain of P. aeruginosa that lacked any tatABC sequences and a short part of PA5071, which is immediately 5′ to tatC (61). Note that the GTG initiation codon of PA5071 overlaps with the last four bases (i.e., GTGA) of the tatC gene. However, deletion of the entire PA5071, which is predicted to encode an rRNA (uridine) methyltransferase, has no discernible phenotype in terms of the secretion of TAT substrates. For example, PlcH and PlcN secretion are entirely intact, and this mutant is as resistant to copper at the wild-type parent PAO1 (A. P. Tomaras and M. L. Vasil, unpublished observations). Furthermore, the PAO1 ΔtatABC mutant described above carrying only the P. aeruginosa tatABC genes without a complete PA5071 gene demonstrates a wild-type phenotype with regard to TAT secretion (61). The sequences of all PCR-amplified fragments were verified by sequencing.

Construction of Burkholderia TAT clones.

Sequences encoding the tatABC genes of Burkholderia pseudomallei were PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA and cloned into a pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) vector in an E. coli Top10 strain. Note that all work involving live B. pseudomallei (i.e., isolation of B. pseudomallei genomic DNA for PCR amplification of its tatABC genes) was performed in a CDC-approved (registration number C20060209-0422) biosafety level 3 (BSL3) laboratory at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. To eliminate an EcoRI site in the vector sequence that would interfere with a later EcoRI-HindIII cloning step (see below), the pCR2.1 Burkholderia clone was digested with BamHI, which has cleavage sites flanking the undesired EcoRI site; the BamHI sites were religated, and the resulting plasmid was transformed into E. coli strain DH5α. An NcoI site was created at the tatA start codon by PCR amplification of a part of the B. pseudomallei TAT clone in pCR2.1 using an upstream primer with the desired initiation codon sequence and a downstream primer located downstream of the unique EcoRI site within tatB. After digestion with NcoI and EcoRI, the PCR product was inserted into a pHERD20T vector that had been cleaved by the same enzymes to create a clone in Top10 cells that contained tatA and part of tatB. Finally an EcoRI-HindIII fragment, containing the rest of tatB and all of tatC from the TAT clone in pCR2.1, was ligated to the similarly digested pHERD20T TAT intermediate and transformed into Top10 cells. The resulting plasmid was used to transform the ΔTAT PAO1 strain described above. Thus, the only difference between the P. aeruginosa and B. pseudomallei TAT clones were the tatABC sequences in the pHERD20T vector.

Arabinose induction assay.

Strains harboring plasmids with the P. aeruginosa or B. pseudomallei tatABC genes in a pHERD20T vector were grown overnight at 37°C on brain heart infusion (BHI) plates supplemented with 750 μg/ml carbenicillin. Approximately 16 h later, 1.2 ml of BHI liquid cultures containing 750 μg/ml carbenicillin were inoculated at an initial A590 (1 cm) of 0.5 and grown at 37°C with shaking during the day so that A590 (1 cm) readings of 3 to 4 were obtained. Approximately 1 ml of these cultures was centrifuged to pellet the cells, which were then resuspended in a HEPES-choline-phosphate medium [0.1 M HEPES (pH 7), 0.5 mM MgSO4, 7 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM succinic acid, 20 mM K2HPO4, 0.2% choline] which contained trace ions (139.1 mM ZnCl2, 1.62 mM MnCl2, 1.78 mM FeCl2, 2.45 mM CaCl2, 4.69 mM H3BO4, and 0.95 mM CsCl) added to a final concentration of 0.1% (vol/vol) (69). The wash step was repeated once, and the final suspension was used to inoculate 10 or more ml of the HEPES medium supplemented with 750 μg/ml carbenicillin so that the initial A590 (1 cm) was 0.05. These cultures were grown in flasks overnight at 30°C with shaking to an A590 (1 cm) of around 1.2 (A600 in plate assay, ∼0.3), and then 1-ml aliquots were distributed to 15-ml culture tubes containing different concentrations of arabinose. Potential Tat-targeting compounds were added at this time in screening assays. There were two separate tubes for each arabinose and compound concentration. The tubes were shaken at 37°C, and 30-μl samples were removed at various time points between 1 and 8 h for PlcH assays performed in triplicate for each tube. The PlcH activity of the sample with compound added relative to the no-compound control was calculated for each arabinose concentration at each of the time points.

Statistical methods.

For compound screening, at least two experiments on separate days were performed. Each experiment had two separate tubes for each arabinose and compound concentration, which were assayed in triplicate, and the PlcH activity of the sample plus compound relative to the no-compound control was calculated. Relative PlcH activity was evaluated statistically using a mixed-effects model on the log transform of the response data (34). The tube was designated the random effect, while arabinose level (low, medium, and high) by dose (none, medium, and high) of the compound was specified as a 9-level factor, or fixed effect. Relative activity was defined as the log of the low, medium, or high arabinose level at each dose, minus the log of the low, medium, or high arabinose level at the 0 dose; these differences were compared at adjacent levels (low versus medium; medium versus high) and evaluated for overall slope (low versus high).

PlcH assays.

Volumes of 30 μl of bacterial culture or supernatant were transferred to a 384-well microplate, and A600 values were read in a Bio-Tek Synergy HT microplate reader. Then 20 μl of NPPC reagent (37.5 mM NPPC, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 40% glycerol) was added to each well, and kinetic time courses were determined by monitoring A410 values for 15 min. Slopes of the linear portions of the kinetic curves were calculated, and PlcH NPPC activity was expressed as ΔA410/min. All measurements were determined in triplicate and averaged.

Generation of TAT antibodies.

Peptides corresponding to different regions of TatA (QPAAQPAQPLNQPHT and CIDAQAQKVEEPARKD) and of TatB (KQEVEREIGADEIR and CTPPSPPSETPRNP) were coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin, antisera were generated in rabbits, and antibodies were affinity purified by Open Biosystems, Inc. Antibodies similarly produced for TatC (using peptides DKPEQPEHDQEMPLVSH and CPDDQPASDGDQPPATRQ) failed to detect any protein by Western analysis of cell extracts.

Western blotting and dot blot analysis of TatA and TatB.

For each time point cell pellets from 30 ml of culture were stored frozen at −20°C. After thawing, cells were resuspended in 2 ml of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and the suspension was disrupted three times by passage through a French press at a pressure of 14,000 lb/in2 at 4°C. The cell debris was pelleted (10 min at 14 000 × g at 4°C), and the supernatant was centrifuged (30 min at 250,000 × g at 4°C). The cell pellet was solubilized in 0.3 ml of 50 mM CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate), 0.1 M KCl, and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5). The suspension was clarified by centrifugation (5 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C). Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). Protein samples, normalized by concentration, were either dot blotted or separated under denaturing conditions on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Optitran; Schleicher and Schuell). The membrane was probed with TatA or TatB affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit was used as the secondary antibody, and bands were detected using an ECL Plus Western blot detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) on an ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini-imager (GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

High-throughput screening for TAT inhibitors.

An HTS assay was initially developed which assesses TAT function by quantifying the activity of PlcH secreted through the TAT system of P. aeruginosa in the presence of small-molecular-weight test compounds. To obtain uniform (i.e., for every well in a 384-well plate) and reproducible levels of PlcH activity in each test well of a large number of 384-well plates, we first deleted the genes encoding both PlcH orthologs of P. aeruginosa (i.e., plcH and plcN) from a PAO1 strain (ADD1976) where a copy of the T7 polymerase gene under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible lacUV5 promoter is chromosomally located (6, 62). We then introduced a plasmid, pADD3268-plcHR, containing the plcHR operon under the control of a T7 promoter, into this PAO1 ADD1976 ΔplcHR variant (6, 62). The plcR gene was included on the plasmid because it encodes a chaperone that is required for the TAT-dependent secretion of PlcH (13, 62). The assay requires two steps: (i) IPTG induction, in the presence of the test compounds in 384-well plates, of PlcH expression in the P. aeruginosa derivative described above and (ii) spectrophotometric quantification at A410 of TAT-secreted PlcH activity with NPPC. A positive result identifying a compound that inhibits TAT-mediated secretion would be read out in the NPPC assay as reduced PlcH activity compared to controls on each test plate that are induced in the absence of compound. A false positive, such as where there is a decrease in PlcH activity without TAT secretion being affected, could arise in a number of ways, including through the inhibition of bacterial growth or by a nonspecific effect on the ability of P. aeruginosa to secrete proteins in general. A compound that directly inhibits PlcH activity itself, although potentially of interest, would also be considered a false positive for the ultimate goal of identifying TAT-specific inhibitors.

The screening was performed in the National Small Molecule Screening and Medicinal Chemistry Core (NSRB) labs of New England Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases at Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. Of the 83,986 compounds that were screened in duplicate, we found 147, including 19 from the natural products libraries and 25 from known bioactive compounds libraries, which resulted in significantly reduced PlcH activity in our NPPC-based assay. Using the 122 positive compounds (excluding the known bioactive), we performed repeats of the initial screening assay and also preliminary secondary screening assays.

Secondary screening of HTS hits.

To determine whether the remaining 122 initial hits were affecting TAT function rather than some indirect cellular mechanism, an array of other phenotypic properties that depend on TAT function were evaluated. Previously identified phenotypic characteristics that are altered in a tatC deletion mutant but not in its parental wild-type or a tatC-complemented strain were evaluated (41, 61). While some of the phenotypic changes identified in a TAT mutant are quite complex and would be difficult to clearly explain in terms of TAT function alone, there were some phenotypes that could manifestly be associated with a particular TAT substrate. For instance, it was determined that a P. aeruginosa tatC mutant is more sensitive to copper than the wild-type parent and that a tatC mutant is unable to utilize choline as a sole carbon and nitrogen source (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material) (41). The sensitivity of the tatC mutant to copper is very likely attributed to the protein PcoA (E. coli ortholog, CopA), which has a TAT signal sequence (i.e., one with twin arginine residues), and is required for copper homeostasis and resistance to this metal in many Gram-negative organisms, including E. coli and P. aeruginosa (41, 52, 63). Also, the proteins encoded by PA2124 and PA3236 in P. aeruginosa, which are predicted to be a choline dehydrogenase and a choline transporter, respectively, like PcoA, have TAT signal sequences (41). Finally, a very obvious phenotype of a TatC mutant of P. aeruginosa is that it no longer produces the extracellular iron siderophore called pyoverdine, which imparts an intense fluorescent green to P. aeruginosa supernatants produced under iron limitation (41, 61). It was ultimately determined that the protein PvdN, encoded by PA2394 and required for the release of pyoverdine into the culture supernatant, has a twin-arginine signal sequence and is a TAT-dependent substrate (66).

The three following phenotypes were examined in a P. aeruginosa wild-type strain (PAO1) in the presence and absence of the hit compounds from the initial HTS: (i) extracellular pyoverdine production (38; also data not shown), (ii) the ability to grow in copper (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and (iii) the ability to grow on choline as a sole carbon and nitrogen source (see Fig. S1). Using these results and those from the repeat experiments of the initial screening assay and the purified PlcH protein inhibition experiments as a guide, we identified 39 lead compounds for further testing.

Development of a TAT titration assay.

Since the above secondary screening assays do not necessarily address whether a compound is acting directly on TAT, we sought to design an assay that would address this issue (i.e., direct inhibition of TAT). To examine the effects of variable expression of the TAT apparatus on PlcH secretion, another strain was constructed where the tatABC genes are deleted, but the native chromosomal plcHR genes remain intact. A plasmid which carries the TAT operon under the control of an araC-PBAD promoter was introduced into this ΔtatABC plcH+ plcN+ P. aeruginosa strain (51). This system was specifically devised to enable us to modulate (i.e., titrate) the levels of the TatABC proteins by introducing various amounts of arabinose. Cultures were grown in a HEPES high-phosphate succinate medium containing 0.2% choline, which is known to induce the expression of the chromosomal plcHR operon (60). Under these growth conditions, TAT-secreted PlcH is the only extracellular enzyme expressed which is active on the NPPC substrate. Consequently, this assay selectively reflects TAT function. Because both plcH and plcN are induced when P. aeruginosa is grown under phosphate (Pi) limiting conditions (60), we used a high-Pi medium to repress expression of plcN, which is active on the NPPC substrate (42) in the assay and is also secreted by TAT (42, 65). High phosphate also represses expression of plcB another phospholipase C of P. aeruginosa, which is secreted through the Sec pathway and cannot cleave NPPC in the pH of the buffer we used in these studies (2). The medium contains succinate, which, in contrast to lactate as a carbon source, initially suppresses induction of plcH by a novel catabolite repression control system (54).

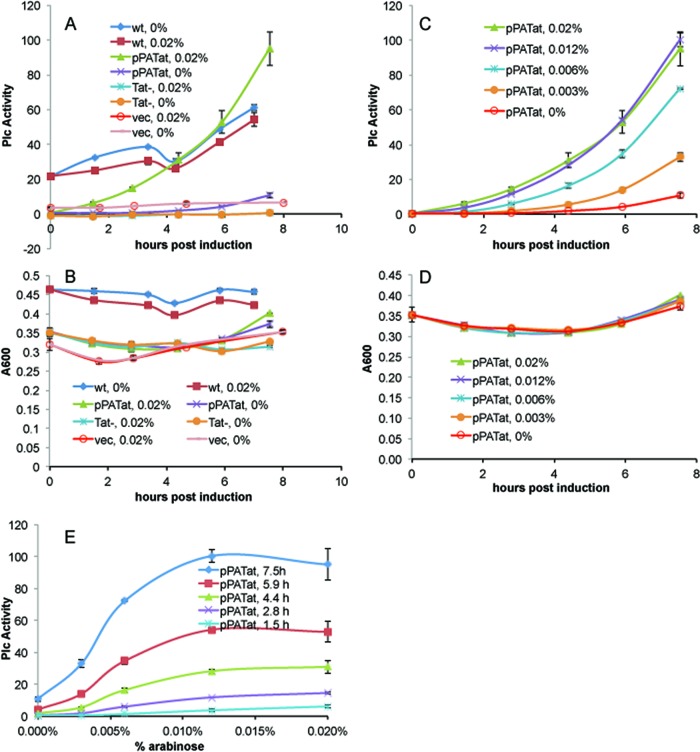

In a typical arabinose induction, cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 ΔtatABC carrying the pPATat plasmid (Table 1) were inoculated into the high-phosphate succinate medium with 0.2% choline at an initial A590 (1 cm) of 0.05 and grown with shaking overnight at 30°C. Approximately 16 h later, the cultures, at an A590 (1 cm) of around 1.2 (A600 in plate assay is ∼0.3), were distributed into separate tubes containing various concentrations of arabinose and grown at 37°C with shaking. Aliquots were removed and assayed at various time points. As shown in Fig. 1A and B, the wild-type P. aeruginosa strain grew faster than the PAO1 ΔtatABC strain with or without the pPATat plasmid or the vector alone. In contrast to all other samples, significant PlcH activity in wild-type cultures was present after the 30°C overnight incubation and increased slightly over the time course. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 ΔtatABC strain lacking the pPATat plasmid had no PlcH activity at any time, thereby confirming the absolute dependence of secreted PlcH activity on TAT function. The strain containing the pHERD20T vector alone in a tatABC deletion background had a low level of activity that changed little over the time course and was unaffected by arabinose. The PAO1 ΔtatABC strain transformed with pPATat, but not induced by arabinose, had an even lower PlcH activity background level than the vector-only control until late in the time course. But the pPATat-containing culture that was induced with 0.02% arabinose produced significant quantities of PlcH activity that continued to increase over the time course.

Fig 1.

Arabinose induction of TAT measured by PlcH activity. PlcH activity (A) and growth (B) curves of wild-type (wt) PAO1, a tatABC deletion mutant (Tat−), and the mutant transformed with either the pPATat or the vector-only plasmid are shown with 0 or 0.02% arabinose added at time zero. The percent arabinose or the time (h) postinduction are indicated after the identifying plasmid or strain for each curve. PlcH activity (C) and growth (D) curves of the arabinose titration of the pPATat transformed deletion mutant are shown with the indicated arabinose concentrations. The data in panel C for five of the time points are replotted to show the dependence of PlcH activity on inducing arabinose concentration (E). Note that the A600 values in panel B are from a plate reader and are not A600 (1 cm). Plc values were determined in triplicate for each of two tubes at each arabinose concentration. The average for each of the two tubes was then averaged.

PlcH activities and growth curves of the strain harboring pPATat titrated with arabinose are shown in Fig. 1C and D. The data in Fig. 1C are replotted in Fig. 1E to show the dependence of PlcH activity on arabinose. The measured PlcH activity reflects the degree of TAT induction. At each of the time points, PlcH activity increased with arabinose concentration. For the later time points, activity increased up to approximately 0.012% arabinose and then leveled off (Fig. 1E). All of the cells with the pPATat plasmid grew at the same rate, regardless of arabinose concentration.

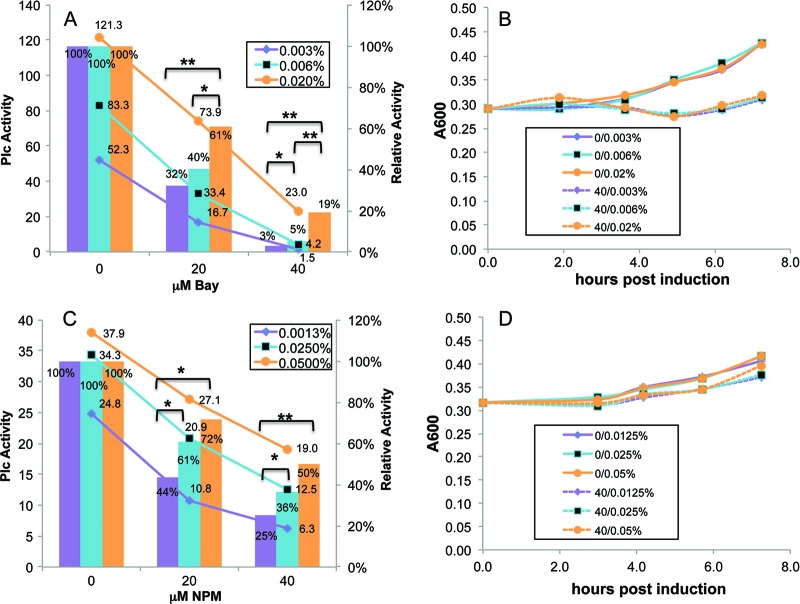

To directly measure the relation between PlcH activity and TAT expression, pPATat cells were induced with 0.004% and 0.2% arabinose and grown at 37°C. After 4.2 h, aliquots were removed, and cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed. Protein samples were electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blot analysis using TatA and TatB antibodies. The Western blot shown in Fig. 2, probed with either TatA or TatB antibodies, shows no bands in the lanes containing extracts from cultures that were not induced with arabinose. However, in extracts of cultures induced by 0.2% arabinose, bands migrating between 15 and 20 kDa for TatA or approximately 25 kDa for TatB were easily detected. Based on known sequences, TatA and TatB proteins are predicted to be 9.2 and 14.9 kDa, respectively. The differences between the predicted sizes and apparent sizes on SDS-PAGE are due to anomalous migration of these membrane proteins, as has been observed with TAT proteins from E. coli (56).

Fig 2.

Detection of induced TAT. A Western blot is shown of protein samples from pPATat cells that were uninduced (lanes 3 and 6) or induced with 0.004% or 0.2% arabinose (ara) for 4.2 h in the HEPES-choline-phosphate medium. After electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with antibodies to TatA or TatB as indicated.

The amount of TatA or TatB observed in the Western blot from the extracts from cultures grown without arabinose was negligible compared to the corresponding intense TAT signals in the 0.2% arabinose lanes, but PlcH activity in the supernatant of the culture without arabinose was 23% of the maximally induced culture with arabinose. This is not necessarily unexpected since PlcH activity saturates at about 0.012% arabinose (Fig. 1), while the induction of TAT proteins likely continues to increase above that concentration. Note that the lanes corresponding to 0.004% arabinose in Fig. 2 are quite faint, but the PlcH activity of that sample was 72% of the 0.2% arabinose-induced culture. Apparently this large amount of arabinose induced saturating amounts of TAT.

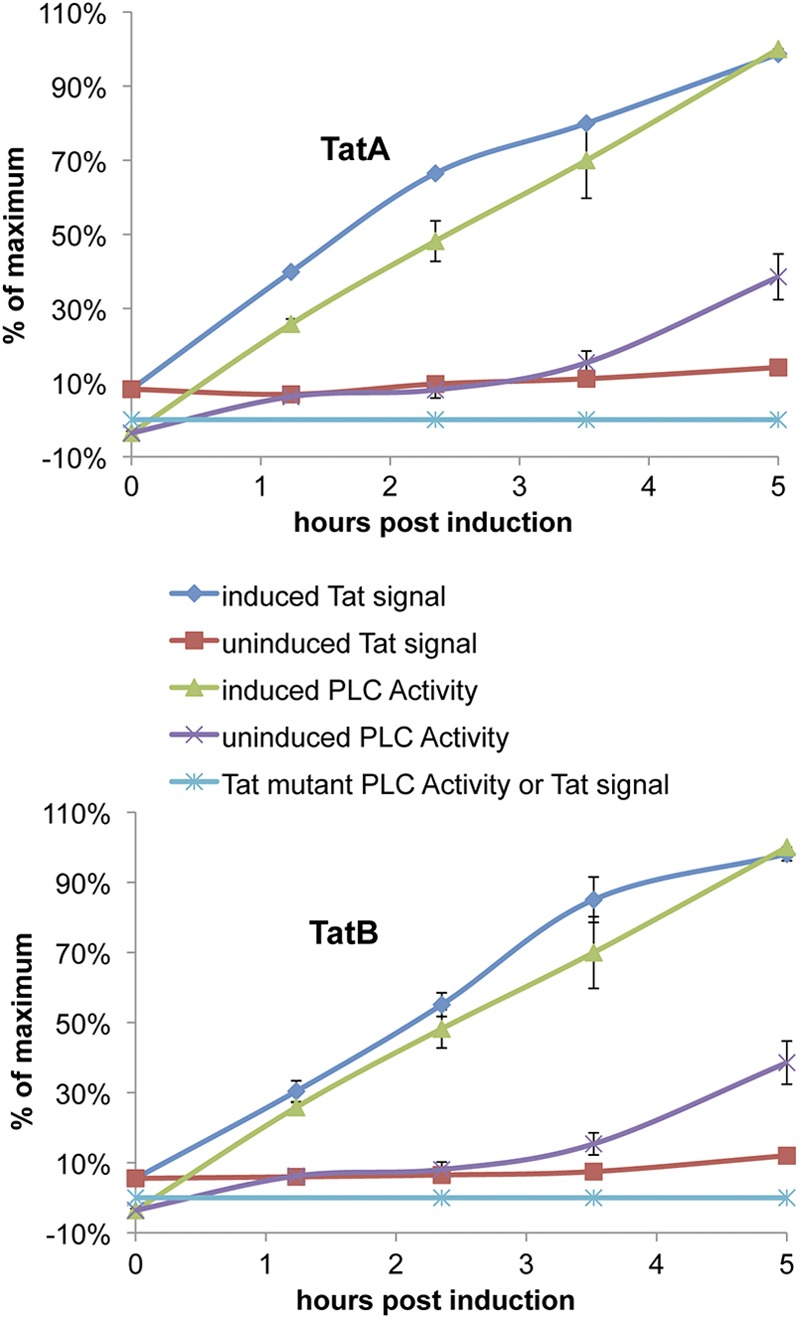

To better quantitatively understand the correlation between PlcH activity and TAT protein production under typical assay conditions, cultures were grown either with or without 0.02% arabinose; at various time points PlcH activities were determined, and cells were collected for lysis and Western quantitative dot blot analysis with TatA and TatB antibodies. As expected, the P. aeruginosa TAT deletion strain lacking a plasmid (Fig. 3) showed neither PlcH activity nor any evidence of the expression of TatA or TatB. However, the same strain carrying the plasmid expressing TatABC revealed a small amount TatA and TatB just before induction, reflecting a low background level of expression that occurred in the overnight growth step of the protocol. There was no detectable PlcH activity in the culture supernatants at this point. Upon arabinose induction there was an approximately linear increase in TatA and TatB protein levels and, followed by a slight lag, a parallel increase in PlcH activity for the next few hours. Cultures without arabinose had a low, but gradually increasing, amount of TatA and TatB and PlcH activity. The PlcH activity detected in the culture supernatants clearly reflects TAT function under these conditions.

Fig 3.

PlcH activity is a good measure of TAT expression. The correlation is shown between TAT protein levels and PlcH activity in cultures of uninduced or induced (0.02% arabinose) tatABC-deleted PAO1 cells carrying pPATat. PlcH activities were measured during induction, and cells were collected for lysis and analysis by dot blotting onto nitrocellulose membranes, which were probed with antibodies to TatA or TatB as indicated. The error bars represent the range of two separate experiments, each of which was analyzed by at least two separate dot blots.

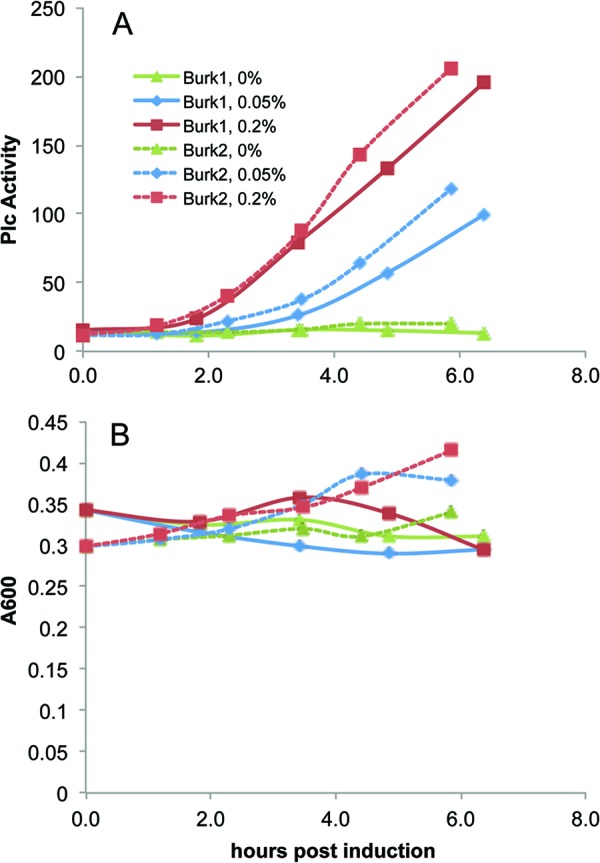

Characterization of a surrogate P. aeruginosa strain expressing TatABC from Burkholderia pseudomallei.

Although we were previously able to complement the pyoverdine-deficient phenotype of a P. aeruginosa TAT mutant with the tatABC genes of E. coli (61), it was of interest to examine the ability of other TAT genes to complement a P. aeruginosa ΔtatABC mutant in a more thorough and precise manner. If the TAT genes from other organisms are indeed able to correct the phenotypes of a P. aeruginosa ΔtatABC strain, this system might be a tractable surrogate that would obviate the need to construct individual ΔtatABC mutants for each organism in order to further test promising inhibitors on other pathogens. For example, an organism such as B. pseudomallei, a class B select agent, requires a higher biosafety level (i.e., BSL3) of containment than P. aeruginosa. Since the TatABC proteins of B. pseudomallei are highly similar to those of P. aeruginosa (TatABC show 78, 64, and 69% sequence similarity over the entire protein, respectively) and since B. pseudomallei expresses three TAT-secreted orthologs of PlcH (31), P. aeruginosa could be a reasonable surrogate for Burkholderia in the initial screen to mitigate the technical difficulties of examining our lead compounds under BSL3 conditions.

Another P. aeruginosa strain was constructed, which harbors the pHERD20T expression vector with the B. pseudomallei tatABC genes under the control of the arabinose-inducible promoter and used to transform the P. aeruginosa ΔtatABC plcH+ strain. We then measured PlcH secretion by this strain. As summarized in Fig. 4 for two representative experiments, cultures of the strain expressing the B. pseudomallei tatABC genes were induced with 0, 0.05, and 0.2% arabinose using a standard assay protocol. The uninduced strain had a small amount of PlcH at the beginning of the induction, which remained essentially unchanged. PlcH levels for the induced strains increased over the approximately 7-h time course in proportion to the amount of added arabinose. Growth curves, also shown in Fig. 4, reveal that little growth occurred over the time course, and there is no obvious dependence on added arabinose. This strain has also been used to screen compounds (data not shown), and the trend in relative PlcH activity with increasing arabinose has been the same as that obtained from using the P. aeruginosa tatABC-containing plasmid (see below).

Fig 4.

B. pseudomallei (Burk) Tat function in a PAO1 strain. The PlcH activities shown in panel A were secreted from cells harboring pBPTat (Table 1) that were uninduced or induced with 0.05% or 0.2% arabinose under standard assay conditions. Data from two separate experiments are shown (Burk1 and Burk2) with the percent arabinose concentration for each curve indicated in the legend. The growth curves are shown in panel B.

Evaluation of lead compounds in the TAT titration assay.

In a typical titration assay, the standard induction assay protocol was followed with cultures induced at three levels of arabinose and with two concentrations of test compound added at time of induction. Culture samples were removed at two to four time points during the approximately 8-h induction and assayed for PlcH activity. If a lead compound directly targets the TAT apparatus, the PlcH activity relative to the no-compound control should increase at a given compound concentration as TAT induction increases. In contrast, if a lead compound acts in an indirect manner (i.e., not on the TAT secretion mechanism directly), then the relative PlcH activity should remain constant or decrease as the arabinose concentration increases. There may be instances where such a clear-cut interpretation may not be valid and thus where even further approaches will be required; nevertheless this assay still provides a powerful tool for the further characterization of TAT inhibitors.

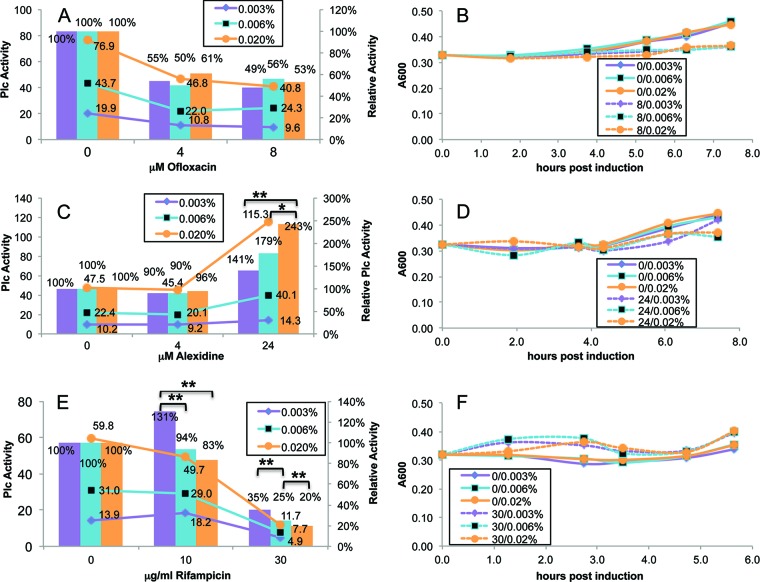

To validate our TAT induction assay, we first examined known bioactive compounds that were hits in the initial screening and were not inhibitors of purified PlcH but were not likely to target TAT. Figure 5 shows representative time points of TAT induction assays of ofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic that inhibits cell division (18), alexidine dihydrochloride, a cationic antimicrobial agent known to disrupt cell membranes (11, 12), and rifampin, which inhibits bacterial transcription (9). Figure 5 shows that the responses of PlcH activities to different arabinose and compound concentrations were as expected: the PlcH activities (Fig. 5, line graphs) increased as arabinose concentrations increased at all compound concentrations, and, for the inhibiting compounds ofloxacin and rifampin, PlcH activities generally decreased as concentrations increased at a given induction level. On the other hand, alexidine dihydrochloride at 24 μM stimulated rather than inhibited PlcH activity. From the results graphed as PlcH activity, relative to results with no compound (Fig. 5, bar graphs), it is obvious that as TAT induction is increased at a fixed compound concentration, relative PlcH activity is constant for ofloxacin and decreasing for rifampin (negative slope). These data provide evidence that these compounds are not TAT selective or specific, as was expected. Each compound was tested in a minimum of two experiments, each on separate days with two to four time points for each experiment (Table S1 in the supplemental material). For each arabinose and compound concentration, two separate tubes were assayed in triplicate, and the PlcH activity of the sample with compound added relative to the no-compound control was calculated.

Fig 5.

Negative controls screened with the TAT titration assay. The standard arabinose induction assay protocol was followed using strains of P. aeruginosa ΔtatABC harboring pPATat. For each of the concentrations of inhibitor compound, the PlcH activity was measured in replicate tubes and averaged. The ratio of the compound-containing sample relative to the no-compound control was calculated for each arabinose concentration at several time points over 4 to 7 h, and values for a representative time point are shown. PlcH values on the left axis are shown in panels A, C, and E as marked line graphs for the three arabinose concentrations indicated by the percentages at the top of the graph and the three compound concentrations on the horizontal axis. PlcH values relative to the no-compound control on the right axis are shown as bar graphs with the statistical significance indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005. The representative time points are at 5.3, 4.3, and 4.7 h, respectively, for panels A, C, and E. Growth curves for the arabinose-induced cultures are shown in panels B, D, and F for the no-compound and highest-compound-concentration samples (indicated by the initial number before the arabinose percentage in the curve-identifying legend) at the three indicated arabinose concentrations. For ofloxacin and rifampin, the relative PlcH activity was constant and decreasing, respectively, as arabinose increased. For the higher concentration of alexidine dihydrochloride, the relative PlcH activity increased with arabinose concentration, but the compound stimulated PlcH activity.

The representative data for ofloxacin in Fig. 5 show no statistically significant changes in relative PlcH activity as arabinose is increased. Analysis of all the ofloxacin data (see Table S1) reveals constant relative PlcH activity with arabinose titration for all but 5 of the 48 measurements. For those five exceptions, relative PlcH activity decreases (negative slope) with increasing arabinose.

For 4 μM alexidine dihydrochloride the relative PlcH activity was constant with increasing TAT induction, but at 24 μM (Fig. 5) the relative activity increased with TAT (positive slope), as shown by P values of 0.04 (comparing PlcH activities at 0.006% and 0.02% arabinose) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and 0.003 (comparing PlcH activities at 0.003% and 0.02% arabinose). This was not interpreted as evidence that increased TAT production can overcome a compound's inhibition of PlcH activity because the effect of alexidine is stimulatory, possibly due to its known membrane disruption properties. Several other 24 μM alexidine data points and one data point at 8 μM in Table S1 also demonstrate an increase in relative PlcH activity with increasing arabinose.

The rifampin data in Fig. 5 show statistically significant (P values ranging from 0.01 to <0.001) decreases in relative PlcH activity with increasing arabinose at both 10 and 30 μg/ml. The rest of the data shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material also support this conclusion.

The growth curves for each of these samples, shown also in Fig. 5, reveal only slight increases in A600 values with time. Growth appears to be independent of arabinose concentration and only slightly affected by compound concentration, depending on the compound. Alexidine dihydrochloride and ofloxacin were hits in the initial screening of known biological agents because of their antimicrobial properties which affected the IPTG induction of PlcH in that protocol much more than the arabinose induction of TAT in the current assay.

The same experiments performed on cultures exposed to a known biologically active agent, Bay 11-7082, yielded different results. That is, relative PlcH activity increased with increasing TAT induction (positive slope), as seen in Fig. 6A (bar graphs), even though the raw data (line graphs) confirm that PlcH activity increased as arabinose increased and decreased as compound concentrations increased. The inhibitory effects of this compound can be alleviated by increased TAT production, thereby strongly suggesting that the compound directly or selectively targets TAT function. Three separate experiments were conducted with Bay 11-7082. All of them showed a statistically significant increase in relative PlcH activity as arabinose concentration, and therefore TAT is increased (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The growth time course for this experiment (Fig. 6B) shows that the compound slightly inhibited growth by 4 h postinduction.

Fig 6.

Possible TAT-targeting compounds screened with the TAT titration assay. The standard arabinose induction assay protocol was followed using strains of P. aeruginosa ΔtatABC harboring pPATat. For each of the concentrations of inhibitor compound, the PlcH activity was measured in replicate tubes and averaged. The ratio of the compound-containing sample relative to the no-compound control was calculated for each arabinose concentration at several time points over 4 to 7 h, and values for a representative time point are shown. PlcH values on the left axis are shown in panels A and C as marked line graphs for the three arabinose concentrations, indicated by the percentages at the top of the graph, and the three compound concentrations on the horizontal axis. PlcH values relative to the no-compound control on the right axis are shown as bar graphs with the statistical significance indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005. The representative time points are at 7.3 and 3 h, respectively, for panels A and C. For Bay 11-7082 (A) and NPM (C), the relative PlcH activity increased as arabinose concentration increased. Growth curves for the arabinose-induced cultures are shown in panels B and D for the no-compound and highest-compound-concentration samples (indicated by the initial number before the arabinose percentage in the curve-identifying legend) at the three indicated arabinose concentrations.

Eight of the 39 compounds selected from the initial 122 hits of the first screen of compounds were maleimides. One of them, N-phenyl maleimide (NPM), was found to be positive in the arabinose induction assay, as shown in Fig. 6C. At both 20 μM and 40 μM NPM, relative PlcH activity increased as the arabinose concentration increased, suggesting that TAT is a likely target of this compound. Additional data in Table S1 for three separate experiments support the same conclusion. The growth curve for one of the experiments (Fig. 6D) shows only slight growth over the time course, which was only slightly diminished by 40 μM NPM.

It is important to note that although the changes in relative PlcH activity as arabinose was titrated were usually consistent between time points (see Table S1 in the supplemental material]), the degrees of inhibition, for all arabinose concentrations at a given compound concentration, often changed with time (data not shown). That is, for time points not shown in Fig. 5 and 6, the slopes of the bars graphs are similar to those shown but were shifted up or down. For the compounds that were positive in the assay, NPM and Bay 11-7082, relative PlcH values generally increased with time, but the same trend of increasing relative values with increasing arabinose at each time point (positive slope) was maintained. For the negative controls ofloxacin and rifampin, relative PlcH values decreased with time, but for alexidine dihydrochloride they were unchanged.

DISCUSSION

The growing emergence of pathogenic bacteria with clinically significant resistance to available antibiotics is a major public health concern. Bacteria still make a major contribution to infectious diseases both as primary (e.g., pneumonia and sepsis) and as exacerbating (e.g., P. aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia in cystic fibrosis) agents. However, the therapeutic options for these life-threatening conditions are increasingly limited, especially in the context of the startling increased resistance to extant chemotherapeutic agents and antibiotics, which is driven by an intense selective pressure to circumvent their lethal effects.

In the past few years, however, there has been a growing interest in the development of alternative therapeutic agents against bacterial infections that do not necessarily target microbial growth or viability but, rather, block the expression or activity of bacterial virulence determinants or mechanisms involved in their secretion.

One of the most notable agents of this sort is a small-molecular-weight compound called virstatin, which blocks the expression of multiple virulence determinants of Vibrio cholerae (i.e., cholera toxin and pili required for colonization) through its interaction with a regulatory factor (i.e., ToxT) (24, 59). Virstatin was first identified from a library of small-molecular-weight compounds in an HTS assay and was shown to be a potent inhibitor of colonization of V. cholerae in a mouse infection model (24). Examples of other targets that have been examined include quorum-sensing systems (39, 40), regulatory factors that control the expression of multiple virulence determinants (e.g., virstatin), and secretion systems (e.g., type III secretion [T3S]) (1), required for the transport of multiple bacterial virulence factors into susceptible hosts. Major human pathogens that use the T3S systems (T3SSs) in infections include Shigella, Salmonella, Chlamydia, Yersinia, P. aeruginosa, Burkholderia spp., and enteropathogenic E. coli.

Notably, the TAT translocation system has also been demonstrated to play a role in the pathogenesis of model infections for many of these pathogens (8, 16, 19, 33, 38, 71). TAT was initially not known to participate in the secretion of extracellular virulence factors (e.g., toxins) beyond the outer membrane. However, we along with our colleagues were first to demonstrate that a potent extracellular toxin (i.e., PlcH) of P. aeruginosa (64) requires the TAT system for its translocation across the inner membrane, where it can ultimately be secreted by the type II (i.e., Xcp) system through the outer membrane (41, 65). We also demonstrated that the TAT translocation system of P. aeruginosa makes a major contribution to its virulence in a chronic pulmonary infection in rats (39).

This report describes the development and use of an HTS assay to identify small-molecular-weight TAT inhibitors based on the detection of a specific TAT substrate (i.e., PlcH) in culture supernatants of the organism that naturally secretes it (i.e., P. aeruginosa). Also illustrated are several follow-up TAT functional assays for the purpose of evaluating compounds initially identified in our HTS assay. While the HTS assay and the additional assays were designed to selectively evaluate TAT function in live organisms, none was able to discriminate between compounds that indirectly had an impact on TAT from ones that were most likely to selectively or specifically inhibit TAT function. Accordingly, we believe that the TAT titration assay described in this report is the only one presently available that is likely to identify compounds which directly or selectively affect TAT function. Although there may be limitations to our assay in terms of the identification of compounds that specifically and exclusively target TAT proteins, it was efficacious in discriminating between our lead compounds that are most likely to target TAT function and ones that clearly do not.

The validity of the assay is supported by the negative-control experiments. Rifampin, a transcription inhibitor, and two compounds, alexidine dihydrochloride and ofloxacin, that were hits in the initial screen but were unlikely to target TAT, based on their known properties, were ruled out by the TAT titration assay. Alexidine and the related compound chlorhexidine are cationic hydrophobic bisbiguanides used as biocides and antiseptics. This antimicrobial agent has a high binding affinity for bacterial cells, and it has been shown that it binds to lipopolysaccharide in Gram-negative bacteria, causing a loss of structural integrity and allowing leakage of cellular materials (11, 12, 21). At the higher concentrations in our assay, alexidine-treated cells exhibited increased PlcH activity over the controls, consistent with leakage through the cell membrane (polymyxin B sulfate, another cationic basic protein which alters membrane structure, was also a hit in our initial screen). It is interesting that although alexidine dihydrochloride's antimicrobial activity has previously been ascribed to its nonspecific disruption of bacterial membranes (21), a recent study reports that it is also a selective and effective inhibitor of PTPMT1, a dual-specificity protein tyrosine phosphatase localized to mitochondria which has been implicated in the regulation of insulin secretion (17). Yet another study links the antifungal activity of alexidine dihydrochloride to possible inhibition of secreted and cytosolic fungal phospholipase B (20). Secreted phospholipase B is a proven virulence factor for the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans, as is PlcH for P. aeruginosa, but the latter (PlcH) is not significantly inhibited by alexidine dihydrochloride (data not shown).

Ofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone antibiotic that functions by inhibiting DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, an enzyme necessary to separate replicated DNA, thereby inhibiting cell division (18). The compound was probably identified in the initial screening due to its antimicrobial properties, but from the TAT titration assay results, it clearly does not target TAT selectively, as would be expected.

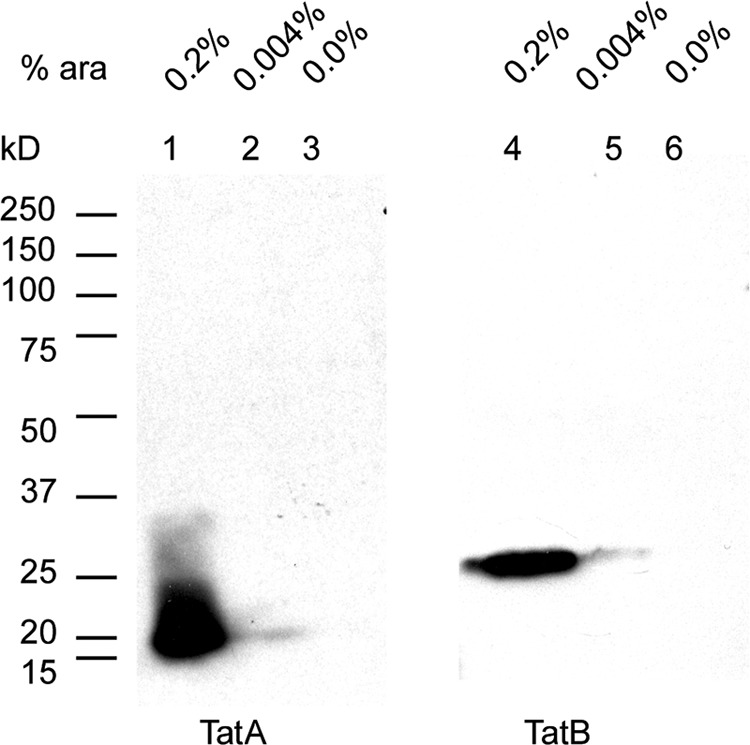

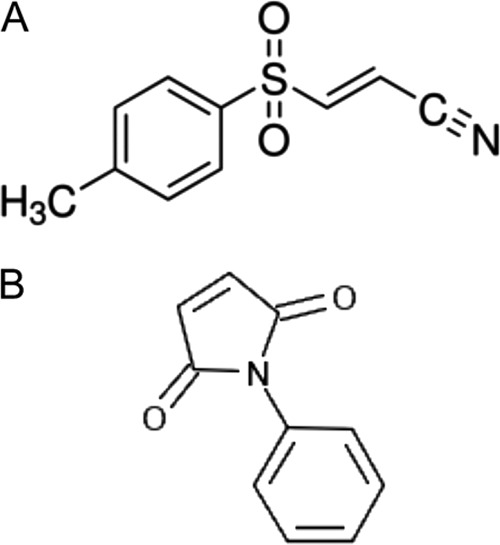

On the other hand Bay 11-7082 (Fig. 7), at a concentrations of 20 μM and 40 μM, was positive in the TAT titration assay, indicating that it likely targets TAT directly. This compound is already known to selectively and irreversibly inhibit NF-κB activation in cell cultures, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of approximately 10 μM (29, 45). In addition, Bay 11-7082 and structurally related vinyl sulfone compounds inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activity in macrophages independent of their effect on NF-κB activity (28). Evidence strongly suggests that Bay 11-7082 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome by alkylation via Michael addition of target nucleophiles at C-2 of Bay 11-7082 and is reactive with cysteine (28).

Fig 7.

The structures of Bay 11-7082 (A) and N-phenyl maleimide (B).

Similarly, the other compound found to be positive in the TAT induction assay, NPM (Fig. 7), belongs to a class of compounds, maleimides, which are reactive with thiols in cysteine. In this reaction, the thiol is added across the double bond of the maleimide to yield a thioether. Maleimides are known to inactivate the bacterial enzyme GlmU, involved in the synthesis of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine, by reacting with cysteine (47), and NPM has been shown to have antibiofilm activity against P. aeruginosa (7). With regard to the effect of this class of compounds (i.e., maleimides) on cysteine, it is noteworthy that there is only a single unpaired cysteine residue in TatC of P. aeruginosa or B. pseudomallei and none at all in TatA or TatB. Consequently, these Cys residues could be a target in the inhibition of TAT function by NPM or the other maleimides we identified in our initial HTS. E. coli TatC has four Cys residues. Although a cysteineless TatC (i.e., Cys → Ala in all four Cys residues of TatC) does not display any observable defects in TAT-mediated translocation (50), in a more recent analysis of TatC of E. coli, Kneuper et al. (30) reported that a Cys23Arg mutation in TatC resulted in inactivation of its function. Also it is worthy of mention that unpaired Cys residues are much more common in the TatC of many bacterial pathogens than the paired Cys residues found in E. coli. As shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material, out of 25 major bacterial pathogens examined, only 5 had paired Cys residues (i.e., 2, 4, or 6) in their TatC orthologs, while 20 had unpaired (i.e., 1, 3, or 5) Cys residues. Although the TAT apparatus is comprised of only three proteins in Gram-negative bacteria and only two in some Gram-positive bacteria, its mechanism is undoubtedly complex since it translocates already folded, cofactored substrates of variable sizes, some of which are dimeric as well. Consequently, further molecular, biochemical, and biophysical (e.g., determination of the molecular architecture of the TAT proteins and the TAT apparatus) investigation of the specificity of the lead compounds identified in this preliminary study will be required to determine precisely how they act on TAT function and whether they are worthy of further consideration as antivirulence agents in vivo.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We very gratefully acknowledge Stephen Lory, Su L. Chiang, and the highly competent staff at the National Small Molecule Screening and Medicinal Chemistry Core (NSRB) labs of the New England Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases (NERCE) at Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, for their outstanding advice and assistance before, during, and after our performance of the HTS assays for TAT inhibitors. We also gratefully acknowledge the expertise and assistance of Pamela Wolfe (Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado Denver) with the statistical examination and presentation of our data. Adriana Vasil is likewise acknowledged for her outstanding technical assistance during this study.

The experiments conducted at the NSRB labs were supported by a grant (U54 AI057159) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to the NERCE and by an NIH (NIAID) supported project (U54 AIO65357) to M.L.V. through the Rocky Mountain Research Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 September 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aiello D, et al. 2010. Discovery and characterization of inhibitors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1988–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barker AP, et al. 2004. A novel extracellular phospholipase C of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is required for phospholipid chemotaxis. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1089–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berks BC, Palmer T, Sargent F. 2005. Protein targeting by the bacterial twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:174–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berks BC, et al. 2000. A novel protein transport system involved in the biogenesis of bacterial electron transfer chains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1459:325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berks BC, Sargent F, Palmer T. 2000. The Tat protein export pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 35:260–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brunschwig E, Darzins A. 1992. A two-component T7 system for the overexpression of genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 111:35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burton E, et al. 2006. Antibiofilm activity of GlmU enzyme inhibitors against catheter-associated uropathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1835–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caldelari I, Mann S, Crooks C, Palmer T. 2006. The Tat pathway of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae is required for optimal virulence. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19:200–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Calvori C, Frontali L, Leoni L, Tecce G. 1965. Effect of rifamycin on protein synthesis. Nature 207:417–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chaddock AM, et al. 1995. A new type of signal peptide: central role of a twin-arginine motif in transfer signals for the delta pH-dependent thylakoidal protein translocase. EMBO J. 14:2715–2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chawner JA, Gilbert P. 1989. A comparative study of the bactericidal and growth inhibitory activities of the bisbiguanides alexidine and chlorhexidine. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 66:243–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chawner JA, Gilbert P. 1989. Interaction of the bisbiguanides chlorhexidine and alexidine with phospholipid vesicles: evidence for separate modes of action. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 66:253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cota-Gomez A, et al. 1997. PlcR1 and PlcR2 are putative calcium-binding proteins required for secretion of the hemolytic phospholipase C of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 65:2904–2913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cuzon G, et al. 2011. Wide dissemination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing β-lactamase blaKPC-2 gene in Colombia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5350–5353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Buck E, et al. 2005. Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia-1 tatB and tatC affect intracellular replication and biofilm formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331:1413–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ding Z, Christie PJ. 2003. Agrobacterium tumefaciens twin-arginine-dependent translocation is important for virulence, flagellation, and chemotaxis but not type IV secretion. J. Bacteriol. 185:760–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doughty-Shenton D, et al. 2010. Pharmacological targeting of the mitochondrial phosphatase PTPMT1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 333:584–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drlica K, Zhao X. 1997. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:377–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dunn AK, Stabb EV. 2008. The twin arginine translocation system contributes to symbiotic colonization of Euprymna scolopes by Vibrio fischeri. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 279:251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ganendren R, et al. 2004. In vitro antifungal activities of inhibitors of phospholipases from the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1561–1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gilbert P, Moore LE. 2005. Cationic antiseptics: diversity of action under a common epithet. J. Appl. Microbiol. 99:703–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holloway BW, Escuadra MD, Morgan AF, Saffery R, Krishnapillai V. 1992. The new approaches to whole genome analysis of bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 79:101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holloway BW, Krishnapillai V, Morgan AF. 1979. Chromosomal genetics of Pseudomonas. Microbiol. Rev. 43:73–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hung DT, Shakhnovich EA, Pierson E, Mekalanos JJ. 2005. Small-molecule inhibitor of Vibrio cholerae virulence and intestinal colonization. Science 310:670–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inglese J, et al. 2006. Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:11473–11478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jongbloed JD, et al. 2002. Selective contribution of the twin-arginine translocation pathway to protein secretion in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:44068–44078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jongbloed JD, et al. 2000. TatC is a specificity determinant for protein secretion via the twin-arginine translocation pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 275:41350–41357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Juliana C, et al. 2010. Anti-inflammatory compounds parthenolide and Bay 11-7082 are direct inhibitors of the inflammasome. J. Biol. Chem. 285:9792–9802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keller SA, Schattner EJ, Cesarman E. 2000. Inhibition of NF-κB induces apoptosis of KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cells. Blood 96:2537–2542 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kneuper H, et al. 2012. Molecular dissection of TatC defines critical regions essential for protein transport and a TatB-TatC contact site. Mol. Microbiol. 85:945–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Korbsrisate S, et al. 2007. Characterization of two distinct phospholipase C enzymes from Burkholderia pseudomallei. Microbiology 153:1907–1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lange C, Muller SD, Walther TH, Burck J, Ulrich AS. 2007. Structure analysis of the protein translocating channel TatA in membranes using a multi-construct approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768:2627–2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lavander M, Ericsson SK, Broms JE, Forsberg A. 2006. The twin arginine translocation system is essential for virulence of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 74:1768–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. 1996. SAS system for mixed models. SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luberto C, et al. 2003. Purification, characterization, and identification of a sphingomyelin synthase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PlcH is a multifunctional enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 278:32733–32743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDonough JA, Hacker KE, Flores AR, Pavelka MS, Jr., Braunstein M. 2005. The twin-arginine translocation pathway of Mycobacterium smegmatis is functional and required for the export of mycobacterial beta-lactamases. J. Bacteriol. 187:7667–7679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McDonough JA, et al. 2008. Identification of functional Tat signal sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins. J. Bacteriol. 190:6428–6438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mickael CS, et al. 2010. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis tatB and tatC mutants are impaired in Caco-2 cell invasion in vitro and show reduced systemic spread in chickens. Infect. Immun. 78:3493–3505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Muh U, et al. 2006. A structurally unrelated mimic of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16948–16952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Muh U, et al. 2006. Novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing inhibitors identified in an ultra-high-throughput screen. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3674–3679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ochsner UA, Snyder A, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. 2002. Effects of the twin-arginine translocase on secretion of virulence factors, stress response, and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:8312–8317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ostroff RM, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. 1990. Molecular comparison of a nonhemolytic and a hemolytic phospholipase C from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 172:5915–5923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Palmer T, Berks BC. 2012. The twin-arginine translocation (Tat) protein export pathway. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:483–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Palmer T, Berks BC, Sargent F. 2010. Analysis of Tat targeting function and twin-arginine signal peptide activity in Escherichia coli. Methods Mol. Biol. 619:191–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pierce JW, et al. 1997. Novel inhibitors of cytokine-induced IκBα phosphorylation and endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression show anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 272:21096–21103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Polotto M, et al. 2012. Detection of P. aeruginosa harboring bla. BMC Infect. Dis. 12:176 doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pompeo F, van Heijenoort J, Mengin-Lecreulx D. 1998. Probing the role of cysteine residues in glucosamine-1-phosphate acetyltransferase activity of the bifunctional GlmU protein from Escherichia coli: site-directed mutagenesis and characterization of the mutant enzymes. J. Bacteriol. 180:4799–4803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pradel N, et al. 2003. Contribution of the twin arginine translocation system to the virulence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 71:4908–4916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Preston MJ, et al. 1995. Rapid and sensitive method for evaluating Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors during corneal infections in mice. Infect. Immun. 63:3497–3501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Punginelli C, et al. 2007. Cysteine scanning mutagenesis and topological mapping of the Escherichia coli twin-arginine translocase TatC Component. J. Bacteriol. 189:5482–5494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Qiu D, Damron FH, Mima T, Schweizer HP, Yu HD. 2008. PBAD-based shuttle vectors for functional analysis of toxic and highly regulated genes in Pseudomonas and Burkholderia spp. and other bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7422–7426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rensing C, Fan B, Sharma R, Mitra B, Rosen BP. 2000. CopA: an Escherichia coli Cu(I)-translocating P-type ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:652–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rholl DA, et al. 2011. Molecular Investigations of PenA-mediated beta-lactam resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Front. Microbiol. 2:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sage AE, Vasil ML. 1997. Osmoprotectant-dependent expression of plcH, encoding the hemolytic phospholipase C, is subject to novel catabolite repression control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 179:4874–4881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Saint-Joanis B, et al. 2006. Inactivation of Rv2525c, a substrate of the twin arginine translocation (Tat) system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, increases beta-lactam susceptibility and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 188:6669–6679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sargent F, et al. 1998. Overlapping functions of components of a bacterial Sec-independent protein export pathway. EMBO J. 17:3640–3650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schaerlaekens K, et al. 2001. Twin-arginine translocation pathway in Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 183:6727–6732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Settles AM, et al. 1997. Sec-independent protein translocation by the maize Hcf106 protein. Science 278:1467–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shakhnovich EA, Hung DT, Pierson E, Lee K, Mekalanos JJ. 2007. Virstatin inhibits dimerization of the transcriptional activator ToxT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:2372–2377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shortridge VD, Lazdunski A, Vasil ML. 1992. Osmoprotectants and phosphate regulate expression of phospholipase C in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 6:863–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Snyder A, Vasil AI, Zajdowicz SL, Wilson ZR, Vasil ML. 2006. Role of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PlcH Tat signal peptide in protein secretion, transcription, and cross-species Tat secretion system compatibility. J. Bacteriol. 188:1762–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Stonehouse MJ, et al. 2002. A novel class of microbial phosphocholine-specific phospholipases C. Mol. Microbiol. 46:661–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Teitzel GM, et al. 2006. Survival and growth in the presence of elevated copper: transcriptional profiling of copper-stressed Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 188:7242–7256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vasil ML, et al. 2009. A complex extracellular sphingomyelinase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits angiogenesis by selective cytotoxicity to endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000420 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Voulhoux R, et al. 2001. Involvement of the twin-arginine translocation system in protein secretion via the type II pathway. EMBO J. 20:6735–6741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Voulhoux R, Filloux A, Schalk IJ. 2006. Pyoverdine-mediated iron uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the Tat system is required for PvdN but not for FpvA transport. J. Bacteriol. 188:3317–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. White GF, et al. 2010. Subunit organization in the TatA complex of the twin arginine protein translocase: a site-directed EPR spin labeling study. J. Biol. Chem. 285:2294–2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Widdick DA, Eijlander RT, van Dijl JM, Kuipers OP, Palmer T. 2008. A facile reporter system for the experimental identification of twin-arginine translocation (Tat) signal peptides from all kingdoms of life. J. Mol. Biol. 375:595–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wilderman PJ, Vasil AI, Martin WE, Murphy RC, Vasil ML. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa synthesizes phosphatidylcholine by use of the phosphatidylcholine synthase pathway. J. Bacteriol. 184:4792–4799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yahr TL, Wickner WT. 2001. Functional reconstitution of bacterial Tat translocation in vitro. EMBO J. 20:2472–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang L, et al. 2009. Pleiotropic effects of the twin-arginine translocation system on biofilm formation, colonization, and virulence in Vibrio cholerae. BMC Microbiol. 9:114 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-9-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.