Abstract

IDX184 is a liver-targeted prodrug of 2′-methylguanosine (2′-MeG) monophosphate. This study investigated the safety, tolerability, antiviral activity, and pharmacokinetics of IDX184 as a single agent in treatment-naïve patients with genotype-1 chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Forty-one patients with baseline HCV RNA ≥ 5 log10 IU/ml, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ≤ 2.5× the upper limit of normal, and compensated liver disease were dosed. Sequential cohorts of 10 patients, randomized 8:2 (active:placebo), received 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg of IDX184 once daily for 3 days, with a 14-day follow-up. There were no safety-related treatment discontinuations or serious adverse events. The adverse events and laboratory abnormalities observed for IDX184- and placebo-treated patients were similar. At the end of the 3-day treatment period, changes from baseline in HCV RNA levels (means ± standard deviations) were −0.5 ± 0.6, −0.7 ± 0.2, −0.6 ± 0.3, and −0.7 ± 0.5 log10 for the 25-, 50-, 75-, and 100-mg doses, respectively, while viral load remained unchanged for the pooled placebo patients (−0.05 ± 0.3 log10). Patients with genotype-1a and patients with genotype-1b responded similarly. Serum ALT levels decreased, especially at daily doses ≥ 75 mg. During the posttreatment period, plasma viremia and serum aminotransferase levels returned to near pretreatment levels. No resistance mutations associated with IDX184 were detected. Plasma exposure of IDX184 and its nucleoside metabolite 2′-MeG was dose related and low. Changes in plasma viral load correlated with plasma exposure of 2′-MeG. In conclusion, the results from this proof-of-concept study show that small doses of the liver-targeted prodrug IDX184 were able to deliver significant antiviral activity and support further clinical evaluation of the drug candidate.

INTRODUCTION

There are an estimated 170 million people worldwide with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, representing a global prevalence of approximately 3%. The annual rate of new infections remains high (about 3 to 4 million/year). Most of those infected develop persistent, chronic infection, and an estimated 20% to 50% of patients are at risk for developing long-term complications, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (18).

The most widely available treatment option for patients with chronic HCV infection is the combination of parenterally administered pegylated interferon and orally administered ribavirin (pegIFN/RBV). Rates of cure, indicated by sustained virologic response (SVR), with this regimen are less than 50% in treatment-naïve patients with the hard-to-treat genotype-1 infection (5, 7). Both pegIFN and RBV have poor tolerability and are not suitable for patients with advanced liver diseases or concurrent medical conditions. Over the past decade, major efforts have been devoted to developing direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) blocking specific steps in the HCV replication cycle. The addition of HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors to pegIFN/RBV has shortened the treatment duration for many patients and has greatly improved SVR rates. However, the protease inhibitors have added significant new morbidities and complex treatment algorithms to an already difficult regimen that continues to be contraindicated for large numbers of patients. Furthermore, treatment failure results in high rates of HCV resistance mutations that can persist for years and potentially limit treatment options (1, 9, 11, 17). Thus, there is an urgent need for simple and better-tolerated oral anti-HCV therapies, which are expected to ultimately eliminate the requirement for pegIFN and possibly RBV.

A number of other promising DAA candidates, including newer HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors, NS5A inhibitors, and nucleoside and nonnucleoside inhibitors of HCV NS5B polymerase, are being clinically evaluated (12, 16). Among various classes of HCV DAAs developed to date, nucleoside HCV polymerase inhibitors have the highest genetic barrier to resistance (8, 13). While this class of DAAs has demonstrated clinical anti-HCV activity, early nucleoside analogs had high systemic exposure and limited formation of active 5′-triphosphate (TP) in the liver (6). IDX184 is a liver-targeted nucleotide prodrug that selectively delivers the 5′ monophosphate (5′-MP) of 2′-methylguanosine (2′-MeG) into hepatocytes. By bypassing the rate-limiting monophosphorylation process, the 2′-MeG-MP is readily converted within liver cells to its active form 5′-TP, a potent and specific HCV polymerase inhibitor. The liver-targeting delivery approach may result in a favorable therapeutic index by increasing the levels of the active 2′-MeG-TP at the site of HCV replication while lowering systemic exposure of the nucleoside, potentially minimizing the risk for systemic side effects (2).

In vitro experiments confirmed that the metabolism of IDX184 to 2′-MeG-MP predominantly takes place in the liver via both cytochrome P (CYP)-dependent and -independent processes and results in enhanced formation (∼100-fold) of the active intracellular 2′-MeG–TP with increased antiviral activity in the HCV replicon assay system (2). In vivo studies in rats and monkeys have shown that, as anticipated, oral IDX184 was largely (approximately 95%) extracted by the liver, with low plasma levels of the nucleoside metabolite 2′-MeG (2).

In a first in-human study, single oral doses of 5 mg to 100 mg of IDX184 were well tolerated by healthy subjects. Human plasma IDX184 and 2′-MeG concentrations were low, consistent with IDX184 being a liver-targeted prodrug. The overall pharmacokinetic profile of IDX184 supported once-daily dosing in HCV-infected patients (19).

The objective of this ascending-dose proof-of-concept study was to evaluate the safety, tolerability, antiviral activity, and pharmacokinetics of IDX184 as a single agent for 3 days in patients with genotype-1 chronic HCV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, sequential-cohort study of four ascending doses (25, 50, 75, and 100 mg) of IDX184 monotherapy. Each dose was administered daily for 3 days. IDX184 and a matching placebo were supplied as white opaque capsules. A 25-mg capsule was provided. At each dose level, members of a cohort of 10 eligible treatment-naïve patients with genotype-1 chronic hepatitis C infection were randomly assigned at an 8:2 ratio to receive IDX184 or a matching placebo once daily. Dose escalation occurred after review of interim safety results from each cohort with an independent steering committee. The sample size of 8 IDX184-dosed patients per cohort had an estimated 83% chance of resulting in observation of a particular adverse event if the expected incidence rate of the event was at least 20%.

Patients were treated for 3 days, with a 14-day follow-up period. Afterward, patients were offered extended therapy with pegIFN/RBV. Those who did not initiate pegIFN/RBV treatment were asked to return for additional follow-up visits at up to 180 days following the last dose of study medication so that plasma samples could be collected for resistance analyses.

Patients.

Major inclusion criteria included the following: male or female adults 18 to 65 years of age, inclusive; a documented clinical history compatible with chronic hepatitis C, including the presence of HCV RNA in the plasma for least 6 months and a liver biopsy sample within 24 months with histology consistent with chronic HCV infection; HCV genotype-1, plasma HCV RNA ≥ 5 log10 IU/ml, and anti-HCV antibody positive at screening; and agreement by patients to use a double-barrier method of birth control for at least 30 days after the last dose of the study drug.

Exclusion criteria included the following: body mass index (BMI) > 32 kg/m2; pregnancy or breastfeeding; coinfection with hepatitis B virus or human immunodeficiency virus; history or evidence of decompensated liver disease; history of HCC or findings suggestive of possible HCC; other causes of liver disease; previous antiviral treatment for HCV infection; current abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs or treatment for opioid addiction; use of any known inhibitor and/or inducer of CYP 3A4 or any other investigational drugs within 30 days of dosing; abnormal laboratory values at screening (a hemoglobin level < 12.0 g/dl for males or < 11.0 g/dl for females; an absolute neutrophil count < 1.5 × 109/liter; a platelet count < 130 × 109/liter; an alanine aminotransferase [ALT] or aspartate aminotransferase [AST] level > 2.5 × upper limit of normal [ULN]; an alkaline phosphatase level > 1.25 × ULN; an albumin level < 3.5 g/dl; total bilirubin, amylase, lipase, or international normalized ratio [INR] > ULN; a serum creatinine or blood urea nitrogen value > ULN; creatinine clearance < 80 ml/min as estimated by the Cockcroft-Gault formula; or any other laboratory abnormality > grade 1, except for asymptomatic cholesterol or triglycerides); or other clinically significant diseases that, in the opinion of the investigator, would jeopardize the safety of the patient or impact the validity of the study results.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the trial centers and conducted in accordance with good clinical practice procedures and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, with authorization from regulatory authorities. The first patient was enrolled on 28 November 2008, and the last patient completed the 2-week follow-up on 10 July 2009.

Safety evaluation.

Safety assessments consisted of collecting data from all adverse events and serious adverse events. Assessments also included regular monitoring of hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis as well as of vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) procedures, and physical examination. Data on concomitant medications were also collected.

Pharmacokinetics evaluation.

Intensive plasma pharmacokinetic assessments were performed over a period of 8 h after the first and third doses, with predose sampling for trough level monitoring. Plasma concentrations of IDX184 and 2′-MeG were measured using a validated liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry methodology as previously described (19). This assay has lower limits of quantification of 0.1 and 0.2 ng/ml for IDX184 and 2′-MeG, respectively. Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters included maximum drug concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (Tmax), concentration 24 h after dosing (C24) for 2′-MeG, area under the plasma concentration-time curve over the dosing interval (AUC24) for 2′-MeG and from time zero to to infinity (AUC∞) for IDX184, and observed half-life (t1/2) over the sampling period.

Antiviral activity evaluation.

The endpoint for assessing anti-HCV activity was the change in plasma HCV RNA level at the end of treatment (24 h after the third dose of IDX184) from baseline (predose on day 0). Plasma samples for measuring HCV RNA were obtained at screening, predose, and 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after the first dose, predose on the second and third dosing days, and 24 h (day 3) after the third dose, as well as during follow-up on day 8 and day 16. Plasma HCV RNA levels were determined by a validated real-time PCR (RT-PCR) assay using the Cobas TaqMan platform, with a dynamic range of 50 to 50,000,000 IU/ml. Plasma HCV RNA levels were not revealed to the investigators and patients until the end of the study.

NS5B sequence analysis.

Population sequencing of the entire HCV NS5B region was performed using plasma samples obtained at predose and on day 3 and day 16 for all patients. As previously described, patients who did not initiate another HCV treatment after the study were asked to return for additional follow-up visits at up to 180 days following the last dose of study medication. If resistance mutations were detected at day 16, additional later samples were available for further analysis.

In addition, clonal sequencing of samples from two IDX184-treated patients with a viral load increase of at least 0.5 log10 above nadir while on treatment was conducted to detect infrequent minor genotypic changes. RNA was isolated from clinical samples using a total nucleic acid isolation kit (Roche Applied Science). The NS5B domain was converted into cDNA by the Roche Transcriptor kit and amplified by nested PCR using the Expand High Fidelity kit.

Statistical analysis.

The safety population was defined as all patients who received at least one dose of the study drug. Safety was analyzed based on the actual treatment received (active or placebo). The pharmacokinetic-evaluable population comprised all patients who received the assigned dose on all scheduled dosing days. The efficacy-evaluable population comprised all patients who received the assigned dose on all scheduled dosing days and who had not received any previous treatment for HCV infection.

Safety, antiviral activity, and pharmacokinetic parameters were summarized for each cohort using descriptive statistics. Data from placebo patients were pooled and summarized. Quantitative pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic dose-response relationships between antiviral activity and drug exposure were also explored using Emax modeling based on the pharmacokinetic population. In this analysis, an Emax model in the form of Ei = Emax × PKi/(EPK50 + PKi) + εi was used. In the equation, Ei is the change in plasma viral load from day 0 to day 3 for each patient i; Emax was fixed to 1.6 log10, the maximum effect achieved with IDX184 after 3 days of treatment in two patients; PKi is the pharmacokinetic parameter of 2′-MeG for patient i; EPK50 is the pharmacokinetic parameter producing 50% of Emax; and εi is the random interpatient error term. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics and disposition.

In total, 41 treatment-naïve patients with genotype-1 chronic HCV infection were enrolled; all received at least one dose of the study drug and therefore constituted the safety population. The demographics and baseline characteristics across the cohorts were generally comparable. Patients were predominately male, Caucasian, and infected with genotype-1a HCV. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristic | Value for indicated IDX184 dose (mg/day) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (placebo) | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | |

| Total no. of patients | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) age in yr | 49 (8) | 48 (7) | 49 (6) | 47 (8) | 47 (8) |

| No. (%) male | 5 (63) | 6 (75) | 7 (88) | 6 (75) | 5 (56) |

| No. (%) of patients of indicated race | |||||

| Black | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 0 | 1 (11) |

| White | 6 (75) | 5 (63) | 5 (63) | 8 (100) | 7 (78) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Mean (SD) BMIa (kg/m2) | 26 (4) | 28 (4) | 28 (3) | 27 (3) | 27 (5) |

| Mean (SD) HCV RNA (log10 IU/ml) | 6.5 (0.7) | 6.5 (0.5) | 6.7 (0.5) | 6.5 (0.3) | 6.4 (0.5) |

| No. (%) of patients infected with HCV genotype: | |||||

| 1a | 5 (63) | 6 (75) | 7 (88) | 7 (88) | 7 (78) |

| 1b | 3 (38) | 2 (25) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 2 (22) |

| Mean (SD) ALT (U/liter) | 45 (28) | 45 (31) | 56 (28) | 55 (24) | 52 (26) |

BMI, body mass index.

Of the 41 dosed patients, 40 completed 3 days of treatment with 14 days of follow-up and 18 of 40 elected not to initiate subsequent treatment for HCV infection and were included in the extended follow-on period of the study.

Three IDX184-treated patients were excluded from efficacy and/or pharmacokinetic analysis: one patient randomized to the 25-mg-dose arm was mistakenly given the 50-mg dose on the first two dosing days and was not dosed on the third day (the only patient who did not complete the treatment course); another patient randomized to the 25-mg-dose arm received a 50-mg dose on the first dosing day and then the correct 25-mg dose on the remaining two days (both patients were excluded from the efficacy- and pharmacokinetic-evaluable populations); and one patient randomized to the 75-mg-dose arm had previously received antiviral treatment for hepatitis C infection and was excluded from the efficacy-evaluable population.

Plasma pharmacokinetics.

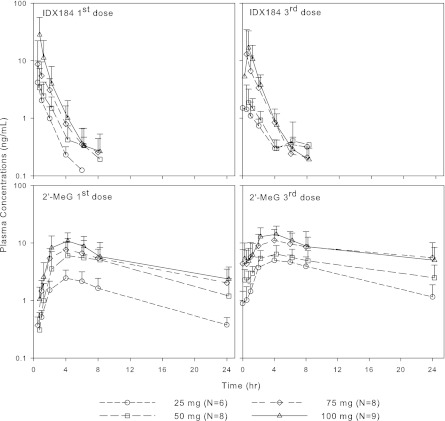

IDX184 is a prodrug that delivers the MP of the nucleoside 2′-MeG in the liver. Therefore, both the parent IDX184 and its nucleoside metabolite 2′-MeG were measured in the blood of HCV-infected patients. Mean + standard deviation (SD) plasma concentration-time curves of IDX184 and 2′-MeG over the 3-day dosing period for the IDX184 doses of 25 to 100 mg/day are depicted in Fig. 1. Summary pharmacokinetic parameters are presented in Table 2. Following once-daily oral dosing for 3 days, the absorption of IDX184 was rapid and was accompanied by the gradual appearance of 2′-MeG. Plasma exposure of both entities was dose related and low, with mean Cmax < 30 ng/ml. Elimination of IDX184 was fast, with comparable levels of exposure on the first and third dosing days; in contrast, 2′-MeG exhibited a longer half-life, leading to approximately 2-fold-higher plasma trough concentrations after the third dose.

Fig 1.

Mean + SD plasma concentration-time profiles of IDX184 (upper panels) and the nucleoside metabolite 2′-MeG (lower panels) in patients with genotype-1 HCV infection.

Table 2.

Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters of IDX184 and the nucleoside metabolite 2′-MeG in patients with genotype-1 HCV infectiona

| Dose (mg/day) | n | PK | Cmax (ng/ml) | Median (range) Tmax (h) | AUC (ng · h/ml) | t1/2 (h) | C24 (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDX184 | |||||||

| 25 | 6b | 1st dose | 3.51 ± 5.82 | 0.60 (0.50–1.02) | 4.34 ± 4.84 | 1.32 ± 0.54 | |

| 3rd dose | 2.19 ± 2.41 | 1.00 (0.52–2.00) | 5.42 ± 0.21 | 2.63 ± 2.57 | |||

| 50 | 8 | 1st dose | 3.85 ± 3.66 | 0.75 (0.50–2.02) | 7.26 ± 4.43 | 1.19 ± 0.28 | |

| 3rd dose | 2.03 ± 1.16 | 1.00 (0.50–2.02) | 4.59 ± 2.20 | 1.56 ± 1.20 | |||

| 75 | 8 | 1st dose | 9.56 ± 13.1 | 0.98 (0.50–2.13) | 14.9 ± 12.0 | 1.13 ± 0.20 | |

| 3rd dose | 12.9 ± 19.8 | 0.98 (0.45–2.00) | 17.1 ± 16.3 | 1.13 ± 0.24 | |||

| 100 | 9 | 1st dose | 26.3 ± 41.1 | 0.57 (0.50–2.02) | 30.3 ± 30.6 | 1.23 ± 0.40 | |

| 3rd dose | 18.3 ± 15.5 | 0.67 (0.50–2.00) | 23.3 ± 15.5 | 1.09 ± 0.41 | |||

| 2′-MeG | |||||||

| 25 | 6b | 1st dose | 2.40 ± 1.05 | 4.00 (2.17–8.00) | 26.7 ± 7.57 | 7.61 ± 2.64 | 0.32 ± 0.03 |

| 3rd dose | 4.96 ± 0.92 | 2.00 (2.00–6.00) | 56.5 ± 14.5 | 7.96 ± 1.19 | 0.91 ± 0.39 | ||

| 50 | 8 | 1st dose | 7.30 ± 2.71 | 5.01 (4.00–8.00) | 84.0 ± 28.8 | 8.04 ± 2.79 | 1.20 ± 0.62 |

| 3rd dose | 6.64 ± 2.59 | 4.00 (2.00–8.00) | 97.9 ± 43.3 | 13.3 ± 6.21 | 2.48 ± 1.65 | ||

| 75 | 8 | 1st dose | 7.78 ± 2.73 | 4.00 (2.00–6.72) | 117 ± 60.3 | 8.34 ± 1.80 | 2.03 ± 1.50 |

| 3rd dose | 11.7 ± 6.70 | 4.00 (1.97–8.00) | 185 ± 144 | 23.3 ± 7.58 | 5.53 ± 4.57 | ||

| 100 | 9 | 1st dose | 11.4 ± 4.85 | 4.07 (2.00–6.00) | 145 ± 59.3 | 9.02 ± 3.83 | 2.36 ± 1.47 |

| 3rd dose | 15.0 ± 5.58 | 4.00 (0.00–4.00) | 189 ± 83.3 | 17.2 ± 9.64 | 4.99 ± 3.41 |

PK, pharmacokinetics; Cmax, maximum drug concentration; Tmax, time to Cmax; C24, concentration 24 h after dosing (2′-MeG only); AUC, area under the plasma concentration-time curve, shown as AUC over dosing interval (AUC24) for 2′-MeG and AUC from time zero to infinity (AUC∞) for IDX184; t1/2, observed half-life over the sampling period. All parameters except Tmax are presented as means ± standard deviations; for Tmax, values are presented as medians (ranges).

Two patients from the 25-mg dose group were excluded from pharmacokinetic analysis; see Results.

Antiviral activity.

A significant decline in plasma HCV RNA levels was observed in all IDX184-treated patients over the 3-day treatment period (Fig. 2). Cohort mean ± SD reductions in plasma HCV RNA levels from baseline at the end of treatment were −0.5 ± 0.6, −0.7 ± 0.2, −0.6 ± 0.3, and −0.7 ± 0.5 log10 for the 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/day doses, respectively. During the same period, placebo patients had virtually no change in plasma viral load (merely a reduction of −0.05 ± 0.3 log10 based on pooled placebo patient results). Descriptively, patients infected with genotype-1a and genotype-1b had similar responses.

Fig 2.

Individual and mean changes from baseline in plasma HCV RNA (log10 scale) over time.

Of note, the two 25-mg-dose subjects who were excluded from the efficacy-evaluable population due to dosing errors (administration of ≥1 dose of 50 mg) had viral load declines of approximately −0.5 log10 at the end of treatment. The third subject (75-mg-dose group), excluded because she was determined to be HCV treatment experienced, had a viral load decline of −1.7 log10 at the end of treatment.

Serum levels of liver ALT and AST decreased from baseline, and the decreases persisted beyond the last dose of study drug. This decline was more pronounced in the groups administered doses of 75 to 100 mg/day. Posttreatment, plasma viremia and serum aminotransferases returned to nearly pretreatment levels.

The antiviral response was further evaluated by fitting an Emax model to the individual pharmacokinetic parameters of 2′-MeG plasma exposure (AUC, Cmax, and C24 following the first and third doses) and viral load reduction on day 3 from baseline. All examined pairs of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic data from this study conformed to the relationship delineated by a typical Emax model, although the C24 after the third dose gave the best fit. As an example, Fig. 3 shows the fitted Emax curve overlapping the actual data for virologic response on day 3 as a function of C24 after the third dose. This relationship indicated that virologic response on day 3 increased rapidly with C24 up to about 5 ng/ml and more gradually thereafter. The estimate (standard error [SE], 95% confidence interval [CI]) for EPK50 was 4.4 (1.0, 2.4 to 6.4) ng/ml.

Fig 3.

Emax dose-response modeling of antivival activity and trough concentrations of 2′-MeG.

NS5B sequence analysis.

The S282T substitution, shown to confer resistance in vitro to the 2′-C-methylribonucleoside class of HCV polymerase inhibitors, including IDX184 (2, 10), was not detected in any sample at any tested time point by population sequencing. Similarly, no other significant genotypic differences between pre- and posttreatment samples or between IDX184- and placebo-treated patients were identified.

Two patients, one from each of the 75- and 100-mg-dose cohorts, experienced an HCV RNA increase of at least 0.5 log10 above nadir (0.5 and 0.7 log10, respectively) while on treatment, with an overall poor response on day 3 (−0.2 to +0.1 log10 change from baseline). The lack of antiviral response did not appear to relate to drug exposure, as both patients had plasma concentrations of IDX184-2′-MeG comparable to the concentrations determined for the rest of patients in their respective dose groups. Using plasma samples from these two patients, clonal sequencing did not detect the S282T substitution and revealed no changes in NS5B variants in response to IDX184 treatment.

Safety and tolerability.

IDX184 administered once daily as a single agent in HCV-infected patients was well tolerated. There were no safety-related treatment discontinuations or serious adverse events reported. No pattern of dose- or treatment-related clinical adverse events or laboratory abnormalities was observed. Table 3 lists the most common treatment-emergent adverse events, regardless of drug relatedness. Adverse events observed in two or more patients were headache, fatigue, diarrhea, and dizziness.

Table 3.

Adverse events in at least 2 patients during treatment

| Adverse event | No. (%) of patients with adverse event(s) during IDX184 treatment at indicated dosage (mg/day) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (placebo; n = 8) | 25 (n = 8) | 50 (n = 8) | 75 (n = 8) | 100 (n = 9) | All activea (n = 33) | |

| Headache | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Fatigue | 1 (12.5) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (6.1) | |||

| Diarrhea | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (3.0) | |||

| Dizziness | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (3.0) | |||

All active, data for all patients administered IDX184.

There were no confirmed grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities. Laboratory parameters were stable over time for all treatment groups. No clinically meaningful changes were observed in vital sign measurements, physical examination findings, or ECG parameters.

DISCUSSION

IDX184 is a liver-targeted prodrug of the nucleotide 2′-MeG-MP. This concept has been validated in vitro using cell-based assays which showed an enhanced formation of the nucleoside triphosphate and an associated increase in anti-HCV activity. In preclinical studies, IDX184-treated animals had very low systemic exposure consistent with a high rate of liver extraction. In addition, significant activity against HCV has been observed in IDX184-treated chimpanzees (14, 15).

The current study was designed as a short-term proof-of-concept trial of the antiviral activity of IDX184 as a single agent in treatment-naïve patients with genotype-1 HCV infection. The selection of doses of from 25 to 100 mg/day was supported by the safety and pharmacokinetic data of a single-dose escalation study in healthy subjects as well as by the animal toxicologic profile of the drug. The duration of this study was capped at 3 days in compliance with the United States Food and Drug Administration's draft regulatory suggestions in place at that time. Since then, monotherapy treatment beyond 3 days with investigational nucleoside-nucleotide analogs has been allowed in early clinical development (3, 4).

In this study, pharmacokinetic evaluation was performed for the first and last doses. The prodrug IDX184 was rapidly absorbed and eliminated in HCV-infected patients, with no accumulation after repeat dosing. Plasma 2′-MeG appeared gradually and declined more slowly, resulting in about 1- to 2-fold-higher peak and total exposures and approximately 2-fold-higher trough concentrations after repeat dosing while approaching the steady state. Plasma levels of both IDX184 and 2′-MeG were dose related and low in HCV-infected patients. While the low plasma concentrations of IDX184 and 2′-MeG are certainly consistent with the intended liver-targeting study design, the role of a saturable absorption process could not be ruled out. Plasma exposures of IDX184 and 2′-MeG in HCV-infected patients were somewhat lower than those of healthy subjects. This is likely due to a food effect recently characterized (data on file). Because of the differences in sampling schedules, which were shorter and less frequent in patients than in healthy subjects, the true terminal phase for 2′-MeG was not observed, resulting in a shorter estimated half-life (19). Nevertheless, the roughly 2-fold-higher trough concentration seen after repeat dosing implies that the elimination process responsible for achieving the steady state is associated with an effective or functional half-life of around 24 h. This was similar to the terminal half-life reported in healthy subjects and recently confirmed in a subsequent phase II clinical study in HCV-infected patients receiving IDX184 for 14 days (data on file).

IDX184 administered for 3 days was able to significantly reduce plasma HCV RNA levels compared with placebo. The number of patients per dose group was too small to allow formal comparison of differences in the responses of patients infected with genotype 1a versus genotype 1b; however, descriptively, there were no differences. The antiviral dose-response activity was more evident for the 25- and 50-mg doses. There was also a trend in improvement in liver function, as evidenced by a decrease toward normal in serum aminotransferase levels which continued for several days after the end of treatment. This was most clearly observed in the 75- to 100-mg dose groups. After treatment, both viral load and serum aminotransferase levels returned to nearly baseline.

During treatment, the apparent lack of a dose response based on mean viral load reduction for doses > 50 mg may have been the result of the small sample size, the relatively narrow dose range tested, and interindividual variability in both antiviral response and drug exposure. When individual antiviral responses were plotted against parameters of plasma 2′-MeG exposure, including AUC, Cmax, and C24, a pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship became apparent. Among the pharmacokinetic parameters examined, the day 3 C24 gave the best fit: higher 2′-MeG trough plasma concentrations predict better antiviral activity. Since the intracellular active triphosphate of 2′-MeG is directly responsible for the anti-HCV activity, a relationship between antiviral activity and plasma 2′-MeG implies a correlation between intracellular 2′-MeG triphosphate and plasma 2′-MeG in HCV-infected patients. Such a correlation was previously found in vivo in mice (data on file) but could not be directly assessed in patients due to ethical concerns and technical challenges preventing measuring triphosphate in human liver. Identification of the plasma trough concentration, which can be determined by a method that is convenient, easy to perform, and less invasive, as a surrogate of the hepatic triphosphate concentration is essential for the clinical development of IDX184.

The signature S282T substitution reported to confer resistance to the 2′-C-methylribonucleoside class of HCV polymerase inhibitors in in vitro studies (10) was not detected as a preexisting variant; neither was it observed in any sample following treatment with IDX184 or placebo. For the 2 patients in the high-dose groups with poor antiviral response, additional clonal sequence analysis was performed but did not detect any relevant changes in NS5B variants prior to versus postdose.

In summary, IDX184 at doses of 25 to 100 mg administered once daily for 3 days in treatment-naïve patients with genotype-1 HCV infection produced significant exposure-related anti-HCV activity and a decrease in serum aminotransferase levels. There were no safety-related treatment discontinuations or serious adverse events and no discernible differences between IDX184 treatment groups and the pooled placebo patients in patterns of adverse events or laboratory abnormalities. There were no clinically significant patterns of ECG abnormalities. No IDX184 resistance-associated mutations were detected. The pharmacokinetic, safety, and antiviral activity data from this short-term proof-of-concept support further longer-term clinical evaluation of IDX184 in the treatment of chronic HCV infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the HCV-infected patients who generously agreed to participate in this clinical study. We also thank the study coordinators, nurses, and staff at clinical study sites.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Bacon BR, et al. 2011. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:1207–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cretton-Scott E, et al. 2008. In vitro antiviral activity and pharmacology of IDX184, a novel and potent inhibitor of HCV replication. J. Hepatol. 48(Suppl 2):S220 [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Medicines Agency (EMEA) 2009. Guideline on the clinical evaluation of direct acting antiviral agents intended for treatment of chronic hepatitis C. European Medicines Agency, London, United Kingdom: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003461.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4. FDA 2010. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection: developing direct-acting antiviral agents for treatment. FDA, Silver Spring, MD: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM225333.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fried MW, et al. 2002. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:975–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Godofsky E, et al. 2004. First clinical results for a novel antiviral treatment for hepatitis C: a phase I/II dose escalation trial assessing tolerance, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of NM283. J. Hepatol. 40(Suppl. 1):S35 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manns MP, et al. 2001. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 358:958–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCown MF, et al. 2008. The hepatitis C virus replicon presents a higher barrier to resistance to nucleoside analogs than to nonnucleoside polymerase or protease inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1604–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Merck & Co. , Inc 2011. Victrelis prescribing information. Merck & Co. Inc., Washington, DC: http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/v/victrelis/victrelis_pi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10. Migliaccio G, et al. 2003. Characterization of resistance to non-obligate chain-terminating ribonucleoside analogs that inhibit hepatitis C virus replication in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 278:49164–49170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poordad F, et al. 2011. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:1195–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodríguez-Torres M. 2010. On the cusp of change: new therapeutic modalities for HCV. Ann. Hepatol. 9(Suppl):123–131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S. 2010. Resistance to direct antiviral agents in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology 138:447–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Standring DN, et al. 2008. Potent antiviral activity of second generation nucleoside inhibitors, IDX102 and IDX184, in HCV-infected chimpanzees. J. Hepatol. 48(Suppl 2):S30 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Standring DN, et al. 2009. Antiviral activity of the liver targeted nucleotide HCV polymerase inhibitor IDX184 correlates with trough serum levels of the nucleoside metabolite in HCV-infected chimpanzees. J. Hepatol. 50(Suppl 1):S37 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thompson A, Patel K, Tillman H, McHutchison JG. 2009. Directly acting antivirals for the treatment of patients with hepatitis C infection: a clinical development update addressing key future challenges. J. Hepatol. 50:184–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc 2011. Incivek prescribing information. Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cambridge, MA: http://pi.vrtx.com/files/uspi_telaprevir.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization 2002. Hepatitis C. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis/whocdscsrlyo2003/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou XJ, et al. 2011. Safety and pharmacokinetics of IDX184, a liver-targeted nucleotide polymerase inhibitor of hepatitis C virus, in healthy subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:76–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]