Abstract

Wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. et Zucc) is the most important germplasm resource for soybean breeding, and is currently subject to habitat loss, fragmentation and population decline. In order to develop successful conservation strategies, a total of 604 wild soybean accessions from 43 locations sampled across its range in China, Japan and Korea were analyzed using 20 nuclear (nSSRs) and five chloroplast microsatellite markers (cpSSRs) to reveal its genetic diversity and population structure. Relatively high nSSR diversity was found in wild soybean compared with other self-pollinated species, and the region of middle and lower reaches of Yangtze River (MDRY) was revealed to have the highest genetic diversity. However, cpSSRs suggested that Korea is a center of diversity. High genetic differentiation and low gene flow among populations were detected, which is consistent with the predominant self-pollination of wild soybean. Two main clusters were revealed by MCMC structure reconstruction and phylogenetic dendrogram, one formed by a group of populations from northwestern China (NWC) and north China (NC), and the other including northeastern China (NEC), Japan, Korea, MDRY, south China (SC) and southwestern China (SWC). Contrib analyses showed that southwestern China makes the greatest contribution to the total diversity and allelic richness, and is worthy of being given conservation priority.

Keywords: Glycine soja, microsatellite, genetic diversity, genetic structure, bottleneck effect

1. Introduction

Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill, Fabaceae], is the world’s most important grain legume crop for its protein and oil [1,2], and its genetic diversity has been declining during processes of domestication and artificial selection [2]. Wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. et Zucc), the ancestor of soybean, retains useful genetic variation for breeding improvement of yield, and resistance to pests, diseases, alkali and salt, and therefore is extremely important germplasm to enrich the soybean gene pool [3].

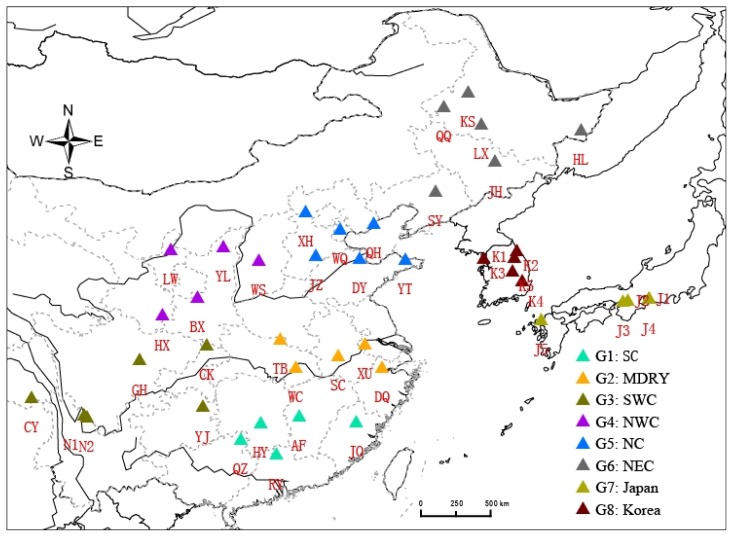

Wild soybean is mainly distributed in the Asiatic Floristic region including most of China (53°–24°N and 134°–97°E) [4], the Korean peninsula, the main islands of the Japanese archipelago and Far Eastern Russia [5] (Figure 1). Wild soybean resources have been severely depleted in China in the last 20 years due to habitat fragmentation [6]. Comparing with surveys in 1979 to 1983, the survey conducted by the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture in 2002 to 2004 revealed large range reductions of wild soybean [7]. For example, the most important populations of wild soybean in Jixian county of Heilongjiang province in China have disappeared following land conversion for agriculture; a large population of 0.02 km2 in the Keshan county of the same province has been almost completely destroyed, and the large population in the Zhangwu county of the Liaoning province in China has disappeared, leading to the permanent loss of the white-flowered soybean type [7]. Wild soybean has been listed as a national second-class protected plant in 1999 in China [8] and the species requires urgent conservation actions.

Figure 1.

Sampling populations of wild soybean.

The genetic diversity and genetic structure of wild soybean have been studied using morphological traits [3,9], isozymes [10], RFLP [11,12], cytoplasmic DNA [11,13] and SSR markers [14–18]. However, these studies were restricted to particular region(s) and most had a limited sample size [19–22]. These studies produced conflicting results with regards to the diversification of wild soybean. For example, the Korean peninsula [14], northeastern China [3], the Yangtze River region [23], and Southern China [24,25] have all been considered as the center of the species’ diversity by different studies. In order to make appropriate conservation recommendations, a study of the level and geographical structure of the genetic variation across the whole species range is urgently needed. Widely distributed across all eukaryotic genomes, the simple sequence repeat (SSR) is a marker of choice for the analysis of genetic variation [26], with more than 1,000 SSRs markers available for wild soybean [27]. We employed 20 nSSRs and five cpSSRs to study: (i) the extent and structure of genetic variation in wild soybean sampled throughout most of its natural range; and (ii) the demographic history of wild soybean to infer historical changes in population sizes.

2. Results

2.1. Equilibrium Test and Genetic Diversity

MICROCHECKER found no evidence of scoring errors, but some samples were detected to have null alleles. We failed to amply these alleles despite two to three more genotyping attempts. Mutations in the flanking region may prevent the primer from annealing to template DNA during amplification of microsatellite loci by PCR [28], but we still kept these loci for further analyses because the frequency was relatively small (<5%). All populations deviated significantly from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p < 0.05), with the observed heterozygosity being lower than expected (mean observed 0.031, range 0.000–0.205 vs. expected 0.426, range 0.018–0.797).

All nSSR loci were polymorphic in all populations. The mean allele richness (AR) and Shannon’s information index (I) were 1.9 (1–3.1) and 0.793 (0.034–1.744), respectively. The fixation index was high (mean 0.913, range 0.202–1). The outcrossing rate was low (mean 8.1%, range 0%–66.4%), but three populations (SY, J2, and K2) showed atypically high outcrossing rate (>48%). The region of MDRY had the highest genetic diversity (AR = 14.0, and I = 2.349). Observed heterozygosity (HO = 0.063) and expected heterozygosity (HE = 0.881) of this region were also higher than other regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genetic diversity parameters estimated at 20 nSSRs and 5 cpSSRs in 43 populations of wild soybean.

| nSSRs | cpSSRs | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Pops | N | A | Na | AR | I | HO | HE | FIS | t (%) | A | Na | AR | I |

| G1:SC | 73 | 199 | 10 | 9.5 | 1.886 | 0.013 | 0.809 | 0.984 | 0.8 | 11 | 2 | 2.2 | 0.421 |

| G1_AF | 15 | 64 | 3 | 1.9 | 0.731 | 0.014 | 0.397 | 0.973 | 1.4 | 6 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.079 |

| G1_HY | 15 | 88 | 4 | 2.4 | 1.177 | 0.014 | 0.605 | 0.979 | 1.1 | 9 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.493 |

| G1_JO | 15 | 45 | 2 | 1.6 | 0.505 | 0.007 | 0.300 | 0.927 | 3.8 | 6 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.079 |

| G1_QZ | 13 | 56 | 3 | 1.9 | 0.751 | 0.015 | 0.456 | 0.969 | 1.6 | 6 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.133 |

| G1_RY | 15 | 36 | 2 | 1.2 | 0.190 | 0.018 | 0.094 | 0.736 | 15.2 | 7 | 1 | 1.3 | 0.098 |

| G2:MDRY | 75 | 292 | 15 | 14.0 | 2.349 | 0.063 | 0.881 | 0.929 | 3.7 | 16 | 3 | 3.1 | 0.742 |

| G2_DQ | 14 | 57 | 3 | 2.0 | 0.792 | 0.051 | 0.468 | 0.904 | 5.0 | 10 | 2 | 2.0 | 0.502 |

| G2_SC | 15 | 114 | 6 | 2.8 | 1.493 | 0.023 | 0.722 | 0.969 | 1.6 | 10 | 2 | 1.9 | 0.369 |

| G2_TB | 15 | 136 | 7 | 3.1 | 1.744 | 0.007 | 0.797 | 0.992 | 0.4 | 14 | 3 | 2.7 | 0.809 |

| G2_WC | 14 | 124 | 6 | 3.0 | 1.616 | 0.053 | 0.762 | 0.933 | 3.5 | 11 | 2 | 2.1 | 0.578 |

| G2_XU | 15 | 114 | 6 | 2.7 | 1.436 | 0.205 | 0.708 | 0.718 | 16.4 | 10 | 2 | 1.9 | 0.402 |

| G3:SWC | 83 | 199 | 10 | 9.3 | 1.884 | 0.035 | 0.803 | 0.956 | 2.2 | 18 | 4 | 3.5 | 0.707 |

| G3_CK | 15 | 57 | 3 | 2.0 | 0.827 | 0.037 | 0.491 | 0.934 | 3.4 | 7 | 1 | 1.3 | 0.149 |

| G3_CY | 12 | 38 | 2 | 1.4 | 0.343 | 0.013 | 0.200 | 0.957 | 2.2 | 7 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.170 |

| G3_GH | 14 | 62 | 3 | 1.9 | 0.761 | 0.048 | 0.426 | 0.759 | 13.7 | 7 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.217 |

| G3_N1 | 12 | 59 | 3 | 1.8 | 0.691 | 0.027 | 0.383 | 0.898 | 5.4 | 12 | 2 | 2.2 | 0.511 |

| G3_N2 | 11 | 52 | 3 | 1.8 | 0.647 | 0.067 | 0.407 | 0.761 | 13.6 | 9 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.375 |

| G3_YJ | 14 | 51 | 3 | 1.8 | 0.663 | 0.014 | 0.414 | 0.914 | 4.5 | 6 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.130 |

| G4:NWC | 75 | 222 | 11 | 10.3 | 1.740 | 0.026 | 0.719 | 0.964 | 1.8 | 13 | 3 | 2.6 | 0.447 |

| G4_BX | 15 | 98 | 5 | 2.4 | 1.162 | 0.028 | 0.570 | 0.962 | 1.9 | 6 | 2 | 2.0 | 0.487 |

| G4_HX | 14 | 97 | 5 | 2.5 | 1.196 | 0.071 | 0.598 | 0.835 | 9.0 | 11 | 2 | 2.1 | 0.475 |

| G4_LW | 15 | 40 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.428 | 0.007 | 0.265 | 0.978 | 1.1 | 11 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| G4_WS | 15 | 76 | 4 | 2.2 | 0.974 | 0.017 | 0.520 | 0.968 | 1.6 | 5 | 2 | 1.7 | 0.342 |

| G4_YL | 15 | 48 | 2 | 1.6 | 0.517 | 0.010 | 0.302 | 0.905 | 5.0 | 9 | 2 | 1.6 | 0.284 |

| G5:NC | 86 | 169 | 8 | 8.1 | 1.633 | 0.009 | 0.730 | 0.989 | 0.6 | 11 | 2 | 2.2 | 0.598 |

| G5_DY | 15 | 68 | 3 | 2.2 | 0.934 | 0.018 | 0.526 | 0.973 | 1.4 | 9 | 2 | 2.0 | 0.518 |

| G5_JZ | 15 | 44 | 2 | 1.9 | 0.674 | 0.018 | 0.455 | 0.930 | 3.6 | 10 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.235 |

| G5_QH | 15 | 49 | 2 | 1.4 | 0.403 | 0.010 | 0.212 | 0.975 | 1.3 | 7 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.157 |

| G5_WQ | 15 | 81 | 4 | 2.3 | 1.072 | 0.003 | 0.555 | 0.995 | 0.3 | 7 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.500 |

| G5_XH | 15 | 48 | 2 | 1.7 | 0.603 | 0.000 | 0.367 | 1.000 | 0.0 | 9 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.276 |

| G5_YT | 11 | 23 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.059 | 0.005 | 0.037 | 0.651 | 21.1 | 8 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| G6:NEC | 89 | 232 | 12 | 10.7 | 1.932 | 0.035 | 0.802 | 0.956 | 2.2 | 17 | 3 | 3.4 | 0.878 |

| G6_HL | 15 | 101 | 5 | 2.6 | 1.303 | 0.037 | 0.658 | 0.946 | 2.8 | 5 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.411 |

| G6_JH | 15 | 108 | 5 | 2.7 | 1.405 | 0.082 | 0.694 | 0.882 | 6.3 | 9 | 2 | 2.0 | 0.434 |

| G6_KS | 15 | 61 | 3 | 2.3 | 0.979 | 0.003 | 0.582 | 0.995 | 0.3 | 11 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.474 |

| G6_LX | 15 | 68 | 3 | 2.2 | 0.930 | 0.028 | 0.520 | 0.958 | 2.2 | 9 | 2 | 2.1 | 0.571 |

| G6_QQ | 15 | 78 | 4 | 2.1 | 0.946 | 0.003 | 0.504 | 0.995 | 0.3 | 11 | 2 | 1.7 | 0.283 |

| G6_SY | 14 | 26 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.118 | 0.061 | 0.076 | 0.202 | 66.4 | 9 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.120 |

| G7:Japan | 70 | 157 | 8 | 7.6 | 1.651 | 0.023 | 0.759 | 0.969 | 1.6 | 10 | 2 | 2.0 | 0.372 |

| G7_J1 | 15 | 63 | 3 | 2.2 | 0.978 | 0.021 | 0.563 | 0.964 | 1.8 | 23 | 2 | 1.6 | 0.343 |

| G7_J2 | 15 | 23 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.034 | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.310 | 52.7 | 8 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| G7_J3 | 15 | 24 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.100 | 0.003 | 0.064 | 0.957 | 2.2 | 5 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| G7_J4 | 15 | 64 | 3 | 2.0 | 0.812 | 0.034 | 0.467 | 0.936 | 3.3 | 5 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| G7_J5 | 10 | 57 | 3 | 2.0 | 0.773 | 0.069 | 0.450 | 0.861 | 7.5 | 5 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.065 |

| G8:Korea | 53 | 204 | 10 | 10.0 | 1.774 | 0.039 | 0.770 | 0.949 | 2.6 | 23 | 5 | 4.6 | 0.932 |

| G8_K1 | 10 | 30 | 2 | 1.2 | 0.163 | 0.000 | 0.090 | 1.000 | 0.0 | 5 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| G8_K2 | 12 | 25 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.049 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.345 | 48.7 | 5 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| G8_K3 | 10 | 34 | 2 | 1.3 | 0.259 | 0.000 | 0.153 | 1.000 | 0.0 | 5 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.000 |

| G8_K4 | 12 | 125 | 6 | 2.8 | 1.513 | 0.092 | 0.708 | 0.872 | 6.8 | 16 | 3 | 2.9 | 0.776 |

| G8_K5 | 7 | 90 | 5 | 2.8 | 1.360 | 0.100 | 0.711 | 0.860 | 7.5 | 16 | 3 | 3.2 | 0.908 |

| Mean | 14 | 65 | 3 | 1.9 | 0.793 | 0.031 | 0.426 | 0.913 | 8.1 | 9 | 2 | 1.6 | 0.297 |

N: number of samples; A: number of alleles; AR: allele richness; Na: number of different alleles; I: Shannon’s information index; HE: expected heterozygosity; HO: observed heterozygosity; FIS: fixation index; t: outcrossing rate.

All cpSSR loci showed relatively low diversity, the mean allele richness (AR) and Shannon’s information index (I) for cpSSRs were 1.6 (1–3.2) and 0.793 (0–0.908). CpSSRs indicated that Korea has the highest allelic richness (AR = 4.6) and Shannon’s information index (I = 0.932) among all regions.

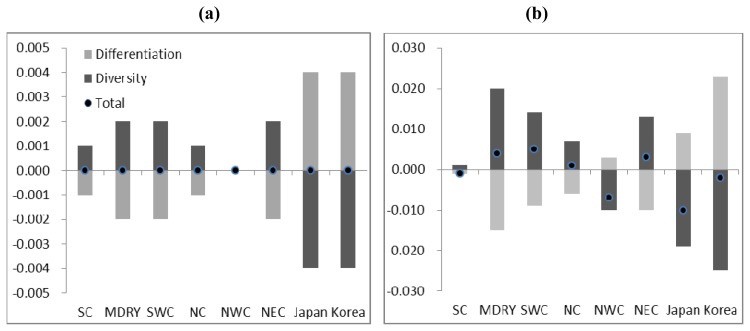

For nSSRs, CONTRIB revealed no difference in regional contribution to total diversity. However, for allelic richness, the highest contribution was made by the SWC region, followed by the regions MDRY and NEC, mainly due to their high own diversity. The lowest contributions came from regions NWC and Japan. For cpSSRs, the SWC region made the greatest contribution to total diversity and allelic richness due to both diversity and differentiation. Besides, the regions of NEC, Korea and Japan made high contributions to allelic richness due to differentiation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Region contribution to the total diversity and allelic richness, (a) and (b) for nSSRs; (c) and (d) for cpSSRs. (a) Contribution to total diversity (CT); (b) Contribution to allelic richness (CTR); (c) Contribution to total diversity (CT); (d) Contribution to allelic richness (CTR).

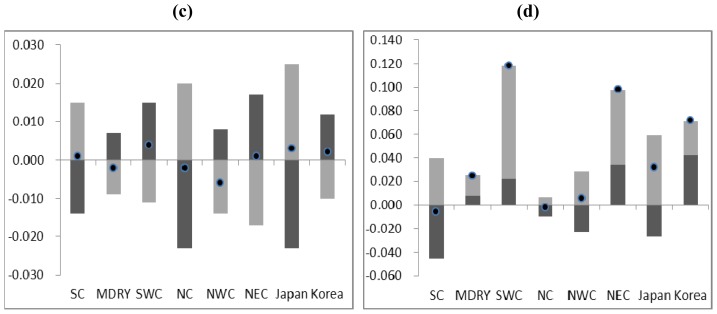

2.2. Population Structure

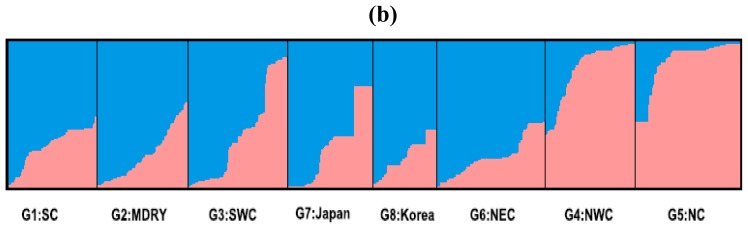

MCMC structure reconstruction of nSSRs showed moderate genetic structure. When Evanno’s [29] ad hoc estimator of the actual number of clusters was used, ΔK indicated modes at K = 2 (Figure 3a). The average percentages of membership for eight geographical regions of individuals in each of the two clusters were calculated. Most samples (>66%) of the group SC, MDRY, SWC, NEC, Japan and Korea were assigned to cluster 1, and most individuals of group NEC (79.4%) and NC (86.5%) to cluster 2 (Table 2, Figure 3b). No geographic structure was detected for cpSSRs. The UPGMA dendrogram of both nSSRs and cpSSRs divided the eight regions into the same two geographical clusters (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Inferred population structure based on 604 samples and 20 nSSRs. (a) DeltaK from STRUCTURE; (b) Genetic structure of wild soybean inferred from the admixture model.

Table 2.

Inferred population structure based on 604 samples and 20 nSSRs.

| Regions | No. of sample | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1: SC | 73 | 0.729 | 0.271 |

| G2: MDRY | 75 | 0.771 | 0.229 |

| G3: SWC | 83 | 0.669 | 0.331 |

| G4: NWC | 75 | 0.206 | 0.794 |

| G5: NC | 86 | 0.135 | 0.865 |

| G6: NEC | 89 | 0.812 | 0.188 |

| G7: Japan | 70 | 0.694 | 0.307 |

| G8: Korea | 53 | 0.772 | 0.228 |

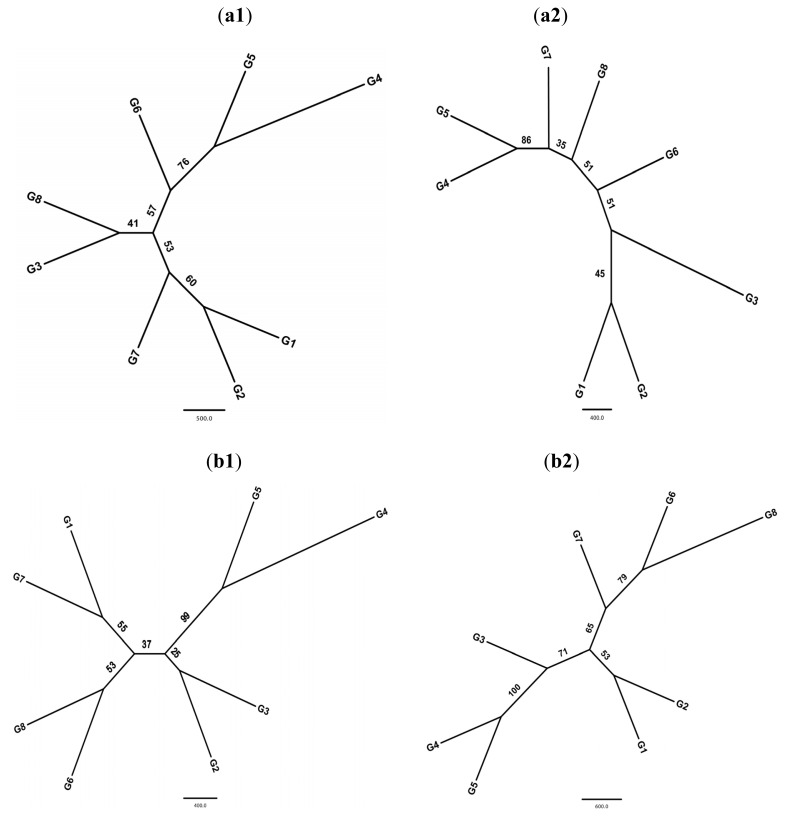

Figure 4.

The UPGMA tree of wild soybeans from different regions. bootstrap values are indicated at each branch. (a) The cpSSR tree basing on eight groups. a1: UPGMA tree; a2: Neighbor-joining tree; (b) The nSSR tree basing on eight groups. b1: UPGMA tree; b2: Neighbor-joining tree.

Analysis of nSSRs by AMOVA revealed that 6.0% of genetic variation was due to the genetic distance between the two clusters, 46.7% among populations within clusters and 47.3% between individuals within populations. Similar results were obtained from cpSSRs (6.8%, 57.0% and 36.25%, respectively) (Table 3). A mantel test indicated a significant isolation by distance for cpSSRs (r2 = 0.021, p = 0.002), but not for nSSRs (r2 = 0.004, p = 0.074).

Table 3.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) for wild soybean.

| Loci | Source of variation | SS | VC | PV (%) | Fixation indices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nSSR | Among two clusters | 393.04 | 0.565 | 5.99 | FCT = 0.060 |

| Among populations within clusters | 5106.23 | 4.409 | 46.69 | FST = 0.527 | |

| Within populations | 5050.64 | 4.469 | 47.32 | FSC = 0.497 | |

| cpSSR | Among two clusters | 68.562 | 0.095 | 6.77 | FCT = 0.068 |

| Among populations within clusters | 935.881 | 0.802 | 56.98 | FST = 0.637 | |

| Within populations | 589.753 | 0.510 | 36.25 | FSC = 0.611 |

The allele size permutation test rendered non-significant differences between FST and RST estimates (p = 0.004 for nSSRs and p = 0.01 for cpSSRs; 10,000 iterations), indicating RST estimates were more appropriate than RST for our data. We found high population genetic differentiation (RST) (cpSSRs: 0.499 and nSSRs: 0.622). For cpSSRs, the overall level of inferred gene flow (Nm) was 0.502 individuals per generation among the populations; and for nSSRs, the gene flow (Nm) was 0.251.

2.3. Demographic History

Standardized differences test and Wilcoxon sign-rank test based on both SMM and TPM model showed recent reduction in seven populations: Chengkou (CK), Wuchang (WC), Tongbai (TB), Keshan (KS), Jizhou (JZ), Japan1 (J1) and Korea5 (K5). A recent bottleneck effect was also detected in three additional populations of Wuqing (WQ), Jiaohe (JH) and Japan 5 (J5) using TPM model by the Wilcoxon sign-rank test (Table 4). The mode-shift test in allele frequency attributed L-shaped distribution to all populations, which was consistent with normal frequency class distribution ranges (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Results from bottleneck tests of nSSRs: Significance of both tests is indicated in bold.

| Populations. | Standardized difference test | Wilcoxm sign test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| TPM | SMM | TPM | SMM | |||

|

| ||||||

| T2 | P | T2 | P | P | P | |

| G1_AF | −2.655 | 0.0040 | −3.014 | 0.0013 | 0.9914 | 0.9959 |

| G1_HY | 0.713 | 0.2381 | 0.307 | 0.3794 | 0.1387 | 0.3108 |

| G1_JO | −0.121 | 0.4519 | −0.303 | 0.3809 | 0.5699 | 0.6282 |

| G1_QZ | 0.434 | 0.3322 | 0.125 | 0.4504 | 0.0715 | 0.2046 |

| G1_RY | −4.223 | 0.0000 | −4.457 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| G2_DQ | 1.498 | 0.0670 | 1.288 | 0.0989 | 0.0521 | 0.0668 |

| G2_SC | 0.967 | 0.1668 | 0.420 | 0.3374 | 0.1081 | 0.2729 |

| G2_TB | 3.360 | 0.0004 | 2.991 | 0.0014 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 |

| G2_WC | 2.651 | 0.0040 | 2.235 | 0.0127 | 0.0007 | 0.0018 |

| G2_XU | 0.854 | 0.1965 | 0.308 | 0.3791 | 0.1841 | 0.4492 |

| G3_CK | 2.755 | 0.0029 | 2.577 | 0.0050 | 0.0014 | 0.0027 |

| G3_CY | 0.146 | 0.4421 | −0.018 | 0.4929 | 0.5898 | 0.5898 |

| G3_GH | −0.211 | 0.4165 | −0.451 | 0.3260 | 0.5235 | 0.6603 |

| G3_N1 | −1.945 | 0.0259 | −2.236 | 0.0127 | 0.9893 | 0.9964 |

| G3_N2 | 0.435 | 0.3317 | 0.122 | 0.4514 | 0.7387 | 0.2899 |

| G3_YJ | 1.164 | 0.1223 | 0.923 | 0.1780 | 0.0770 | 0.0982 |

| G4_BX | −1.439 | 0.0751 | −2.067 | 0.0194 | 0.7793 | 0.8533 |

| G4_HX | −0.109 | 0.4567 | −0.624 | 0.2665 | 0.4159 | 0.6802 |

| G4_LW | −0.069 | 0.4726 | −0.201 | 0.4203 | 0.4816 | 0.4816 |

| G4_WS | −0.194 | 0.4233 | −0.643 | 0.2602 | 0.2450 | 0.2839 |

| G4_YL | −0.740 | 0.2295 | −0.965 | 0.1673 | 0.7378 | 0.7378 |

| G5_DY | 0.919 | 0.1790 | 0.557 | 0.2886 | 0.0844 | 0.1127 |

| G5_JZ | 4.755 | 0.0000 | 4.642 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| G5_QH | −5.224 | 0.0000 | −5.543 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| G5_WQ | 1.411 | 0.0791 | 1.071 | 0.1421 | 0.0407 | 0.0649 |

| G5_XH | 1.371 | 0.0851 | 1.206 | 0.1139 | 0.0523 | 0.0523 |

| G5_YT | −0.485 | 0.3140 | −0.512 | 0.3043 | 0.8125 | 0.8750 |

| G6_HL | −0.230 | 0.4089 | −0.844 | 0.1993 | 0.5218 | 0.8529 |

| G6_JH | 1.447 | 0.0739 | 0.977 | 0.1642 | 0.0181 | 0.0570 |

| G6_KS | 4.213 | 0.0000 | 4.054 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| G6_LX | 0.935 | 0.1749 | 0.648 | 0.2584 | 0.0978 | 0.2090 |

| G6_QQ | −3.357 | 0.0004 | −4.032 | 0.0000 | 0.9976 | 0.9994 |

| G6_SY | −0.227 | 0.4102 | −0.378 | 0.3528 | 0.4375 | 0.4375 |

| G7_J1 | 3.089 | 0.0010 | 2.903 | 0.0019 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| G7_J2 | −1.720 | 0.0428 | −1.768 | 0.0385 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| G7_J3 | 0.979 | 0.1637 | 0.910 | 0.1815 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 |

| G7_J4 | −0.924 | 0.1777 | −1.336 | 0.0907 | 0.5938 | 0.7392 |

| G7_J5 | 1.356 | 0.0875 | 1.110 | 0.1335 | 0.0327 | 0.0523 |

| G8_K1 | −2.512 | 0.0060 | −2.579 | 0.0050 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| G8_K2 | −3.161 | 0.0008 | −3.282 | 0.0005 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| G8_K3 | −1.969 | 0.0245 | −2.058 | 0.0198 | 0.9480 | 0.9710 |

| G8_K4 | −0.755 | 0.2253 | −1.373 | 0.0848 | 0.6079 | 0.7848 |

| G8_K5 | 3.511 | 0.0002 | 3.299 | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 |

SS: sum of squares; VC: variance component; PV: percentage of variation;

p < 0.001; FCT: genetic diversity between two clusters; FSC: differentiation among populations within clusters; FST: divergence among all populations. Significant for both tests are in bold.

3. Discussion

3.1. Genetic Diversity in Wild Soybean

The genetic diversity of wild soybean was studied previously using SSRs [21,25,26,30,31]. However, this is the first time a study uses both nuclear and plastid SSRs to analyze the extent and structure of genetic variation across the whole species range. Wild soybean showed a relatively high population diversity (HE = 0.426), which is similar to the result from previous studies [31,32], Considering life form and breeding system have a highly significant influence on genetic diversity [33], we compared genetic diversity of wild soybean with other predominantly self-pollinated wild species, such as wild emmer (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides) (HE = 0.19) [34], wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) (HE = 0.138) [35], and officinal wild rice (Oryza officinalis) (HE = 0.22) [36]. This may be caused by the special seed dispersion of the wild soybean, the pod dehiscence could discharge the mature seeds to a distance of 0–5 m (up to 6.5 m) [22]. High outcrossing rate for certain populations maybe another reason for high genetic diversity in wild soybean.

The nSSRs showed that MDRY region has the highest diversity, which is consistent with several previous studies. For example, Shimamoto et al. [13] reported the highest diversity in the Yangtze River region using RFLP markers. Southern China (including regions of MDRY, SWC and SC) was proposed as the wild soybean center of genetic diversity in a study by Wen et al. [37] using a combination of SSRs and morphological traits. The same region was also pointed as origin and center of diversity using SSR markers and nucleotide sequences in a study by Guo et al. [25]. Compared with previous results, our study applied more detailed regional division, and the center of diversity was similar, but not as obviously different than in previous studies.

Compared with nSSRs (AR = 1.9; I = 1.794), the cpSSRs showed less diversity (AR = 1.6; I = 0.932), which is congruent with Powell et al. [38], who used both nSSRs and cpSSRs of wild soybean samples from a germplasm bank. Similar results have been observed in other studies using both types of SSR markers in other species [39–41]. This is consistent with low substitution rate of plant chloroplast cpDNA sequences compared with nDNA [42]. The cpSSRs could offer unique insights into ecological and evolutionary processes in wild plant species in some situation [43], Differing from that of nSSRs, cpSSRs revealed that Korea has the highest wild soybean genetic variation.

3.2. Genetic Structure of Wild Soybean

Breeding system, life form, effective population size, genetic drift and gene flow are the major evolutionary effects on population genetic structure, with the effect of breeding system being the predominant one [44,45]. Populations of self-fertilizing species are expected to have lower allelic diversity, lower levels of heterozygosity, and high differentiation among populations than populations from outbreeding species [45]. Here, both nSSRs and cpSSRs showed high inter-population genetic differentiation and low gene flow, as expected in the predominantly selfing wild soybean, combined with low seed and pollen dispersal ability. The seed dispersal distance of wild soybean is short, and 95%, 99%, and 99.9% of the produced seeds disperse within 3.5, 5.0, and 6.5 m, respectively after natural pod dehiscence [22], and nearly 81.4% of the loci were found to be positively correlated in the first two distance classes (0–10 m) [6]. Low pollen dispersal ability can be surmised from the estimates of outcrossing rate in wild soybean, which varied from 2.3% (range 2.4%–3.0%) [46] to 13% (range 9.3%–19%) [47] using allozymes and 3.4% (range 0%–37.4%) applying nSSRs [21]. We found a higher mean outcrossing rate (8.1%), with extremely high values in some populations (G5_YT: 21.1%; G6_SY: 66.4%; G7_J2:52.7%; G8_K2: 48.7%). Despite high selfing rates, occasional outcrossing rate can be subsequent. Occasional high outcrossing was detected in other predominant self-pollinated species such as wild barley (t = 25.1%) [48]. The high outcrossing rate in some populations of a predominantly selfing species can be a consequence of rare or sporadically occurring specific environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, wind, insect pollination, etc.) [48]. In this study, the populations with high outcrossing rate were found in different habitats from all eight eco-regions, and could not be ascribed to a particular abiotic environmental factor, which can suggest an importance of some biotic factor such as high pollinator visiting activity [6], more studies should be carried out to fully resolve this issue.

The UPGMA and Neighbor-joining dendrogram based on Nei’s genetic distance and assignment test revealed two clusters of wild soybean in both nSSRs and cpSSRs. One cluster was formed by the NC and NWC regions, and the other one was formed by six geographic regions including NEC, SWC, SC, MDRY, Korea and Japan. The absence of differentiation among East China, Southern Japan and the Korean Peninsula (CJK region) is surprising. Fluctuations in sea level among the CJK region throughout the Quaternary (or even in the mid-late Tertiary) provided abundant opportunities for population fragmentation and allopatric speciation at the CJK region. Applying nDNA and cpDNA sequences, the previous phylogeographic studies on Croomia japonica [49], Kirengeshoma palmata [50], and Platycrater arguta [51] suggested deep allopatric-vicariant differentiation of disjunct lineages in the CJK region [52]. Wild soybean might have seen a continuous distribution throughout the CJK region through the exposed East China Sea (ECS) basin when the sea level fell by 85-130/140 meters during Last Glacial Maximum (LGM; 24,000–18,000 years before present) [53,54], the disjunct distribution among this region formed following the submergence of ECS land bridge, and there may be insufficient time for lineage sorting and differentiation. Wild soybean has salt resistance [55], and could grow easily in the salty conditions of a sea shore hence they have more chance to migrate along the land bridge among the CJK regions during glacial periods. We could not totally exclude the possibility of exchange of wild soybean among the CJK region via long distance dispersal due to disappear of the ECS land bridge. However, it is just a speculation and will need further studies.

3.3. Conservation Implications

In this study, a bottleneck effect was detected in seven populations: Chengkou (CK), Wuchang (WC), Tongbai (TB), Keshan (KS), Jizhou (JZ), Japan 1 (J1) and Korea 5 (K5). The CK and JZ populations are from undisturbed habitats with very small population sizes, while another five populations are situated in disturbed habitats: populations WC, J1 and K5 are along roadsides; population AF is beside an abandoned railway; populations KS and TB are along the ridge of some fields. Population KS is a relic from a larger population predating farming reclamation, and only limited individuals are left. In brief, the five populations were significantly affected by anthropological activities. Wild soybean can adapt to a wide variety of habitats with adequate water. However population size of wild soybean will rapidly decrease in the habitat, with subsequent degradation of genetic diversity and allelic richness. Conversation of wild soybean is therefore a priority, and should focus on regions already affected genetically.

When selecting conservation sites one must also consider a population’s contribution to total diversity and allelic richness. The SWC region was inferred to have greatest contribution to total diversity and allelic richness with both nSSRs and cpSSRs. Wild soybean in this region shows an unusually small population size, combined with a fragmented distribution: several populations from Ninglang county of Yunnan province and Chayu county of Xizang province are separated from the main populations by as much as 400 km. Furthermore, both previous ex situ and in situ conservation initiatives have paid little attention to this region, and only dozens (from a total of 6172) of wild soybean seed accessions from this region have been collected and stored in the Chinese Crop Germplasm Resources databank (http://icgr.caas.net.cn/cgrisintroduction.html). This region deserves high conservation priority.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Samples Collection, DNA Extraction and Microsatellite Genotyping

A total of 604 wild soybean individual leaf samples were obtained from 43 populations across most of the species distribution (Figure 1). Five populations represented two countries, Korea and Japan, and 5 to 6 populations represented each of six regions of China (Table 5). Total genomic DNA was extracted from silica gel-dried leaves using the CTAB method of Doyle and Doyle [56]. The extracted DNA was resuspended in 0.1× TE buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, PH 8.0, 1 mmol/L EDTA) to a final concentration of 50–100 ng/μL.

Table 5.

Locations and habitats of sampled wild soybean populations.

| Geographical region | Population name | Location of sampling | Longitude | Latitude | Altitude (m) | Habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1: SC | Population AF | Anfu county, Jiangxi province | 27.388 | 114.602 | 85 | Beside road |

| Population JO | Jianou county, Fujian province | 26.962 | 112.153 | 126 | Beside river | |

| Population HY | Hengyang county, Hunan province | 27.024 | 118.293 | 123 | Beside river | |

| Population RY | Ruyuan county, Guangdong province | 25.872 | 110.862 | 510 | Beside road | |

| Population QZ | Quanzhou county, Guangxi province | 24.919 | 113.136 | 722 | Beside road | |

|

| ||||||

| G2: MDYR | Population WC | Wuchang district, Hubei province | 30.549 | 119.972 | 15 | Beside road |

| Population XU | Xuanwu district, Jiangsu province | 31.314 | 117.128 | Waste land | ||

| Population DQ | Duqing county, Zhejiang province | 32.370 | 113.400 | 15 | Beside canal | |

| Population SC | Shucha county, Anhui province | 30.521 | 114.395 | 45 | Beside road | |

| Population TB | Tongbai county, Henan province | 32.045 | 118.861 | 33 | Beside road | |

|

| ||||||

| G3: SWC | Population CK | Chengkou county, Chongqing | 31.983 | 108.667 | 805 | Valley |

| Population YJ | Yinjiang county, Guizhou province | 30.996 | 104.349 | 458 | Valley, | |

| Population GH | Guanghan city, Sichuan province | 28.000 | 108.406 | 458 | Beside river | |

| Population CY | Chayu county, Xizang province | 28.600 | 97.400 | 1685 | Unknown | |

| Population NL1 | Ninglang county, Yunnan province | 27.455 | 100.758 | 2600 | Beside filed | |

| Population NL2 | Ninglang county, Yunnan province | 27.340 | 100.954 | 2550 | Beside filed | |

|

| ||||||

| G4: NWC | Population BX | Bingxian county, Shaanxi province | 35.040 | 108.077 | 835 | Valley, |

| Population HX | Huixian county, Gansu province | 33.893 | 105.826 | 1126 | Canal | |

| Population LW | Lingwu county, Ningxia province | 38.146 | 106.326 | 1103 | Canal | |

| Population WS | Wenshui county, Shanxi province | 37.417 | 112.017 | 759 | Beside canal | |

| Population YL | Yulin city, Shanxi province | 38.281 | 109.738 | 1051 | Along river | |

|

| ||||||

| G5: NC | Population JZ | Jizhou county, Hebei province | 37.574 | 118.524 | 23 | Beside road |

| Population DY | Dongying city, Shandong province | 37.742 | 115.686 | 6 | Beside ditches | |

| Population WQ | Wuqing district, Tianjing | 39.808 | 119.432 | −6 | Beside ditches | |

| Population XH | Xuanhua county, Hebei province | 39.449 | 117.249 | 601 | Beside river | |

| Population QH | Qinghuangdao city, Hebei province | 40.593 | 115.021 | 18 | Beside river | |

| Population YT | Yantai city, Shandong province | 37.485 | 121.453 | 10 | Wasteland | |

|

| ||||||

| G6: NEC | Population LX | Lanxi county, Heilongjiang province | 41.893 | 123.411 | 139 | Beside pond |

| Population JH | Jiaohe county, Jinlin province | 45.849 | 132.762 | 126 | Beside river | |

| Population KS | Keshan county, Heilongjaing province | 43.808 | 127.237 | 325 | Aside field | |

| Population QQ | Qiqihaer city, Heilongjiang province | 48.283 | 125.498 | 304 | Beside river | |

| Population HL | Hulin city, Heilongjiang province | 46.218 | 126.338 | 73 | Beside filed | |

| Population SY | Shenyang, Liaoning province | 47.341 | 123.940 | wasteland | ||

|

| ||||||

| G7: Japan | Population J1 | Kanagawa, Japan | 34.960 | 137.160 | 12 | Wet Land |

| Population J2 | Tokyo, Japan | 34.828 | 135.770 | 35 | Wet Land | |

| Population J3 | Hirakata, Osaka, Japan | 34.810 | 135.480 | 11 | Wet Land | |

| Population J4 | Okazaki, Japan | 34.959 | 137.139 | 37 | Wet Land | |

| Population J5 | Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan | 33.597 | 130.215 | Unknown | ||

| Population K1 | Gangwon-do, South Korea | 37.625 | 128.492 | 520 | Wet Land | |

| Population K2 | Gangwon-do, South, Korea | 38.031 | 128.639 | 340 | Wet Land | |

| Population K3 | Incheon, South Korea | 37.533 | 126.497 | 11 | Wet Land | |

| Population K4 | Yeongcheon-si city, Korea | 36.113 | 128.982 | 102 | Along road | |

| Population K5 | Moonkyeong-si city, Korea | 36.721 | 128.358 | 77 | Along road | |

G1: SC, south China; G2: MDYR, Middle and lower reaches of Yangtze River; G3: SWC, southwestern China; G4: NWC, northwestern China; G5: NC, north China; G6: NEC, northeastern China.

Genotyping was performed using 20 nSSRs representing all 20 wild soybean linkage groups corresponding to the 20 chromosomes, and five cpSSRs from intergenic regions. All the 25 loci are polymorphic and have been used in previous studies [15,21,57] (Table 6). PCR reactions were performed in 15 μL reactions containing 30–50 ng genomic DNA, 0.6 μM of each primer, 7.5 μL 2× Taq PCR MasterMix (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). PCR amplifications were conducted under the following conditions: 94 °C for 2 min; 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. Primers are shown in Table 6. All the SSR markers were polymorphic based on electrophoresis performed on an ABI 3730 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Fragment length sizes were scored automatically using the program GeneMapper (Applied Biosystems).

Table 6.

Characteristics of the 25 microsatellite loci for wild soybean. Forward (F) and reverse (R) primer sequences, repeat motifs, size range and linkage group are given.

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Repeat motif | Size range | linkage group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gmcp1 | F:TCGATTCTATGCCCCTACTT R:AGACTCCCAAGTTTTCAGTCG |

(T)12 | 124–126 | TrnT/trnL |

| gmcp3 | F:GCTTCAGAATTGTCCTATTTA R:ATCAAATAACGCCTCATCTA |

(A)12CG(T)11 | 103–113 | TrnT/trnL |

| gmcp4 | F:TATCACTGTCAAGATTAAGAG R:CTTTTATATGTATGGCGCAAC |

(A)11 | 127–136 | atpB/rbcL |

| RD19 | F:CTAAATATTACAAAATGGAATTCT R:ACCAATTCAAAAAATCGAATA |

(A)14 | 149–151 | rps19 |

| SOYCP | F:CATAGATAGGTACCATCCTTTTT R:CGCCGTATGAAAGCAATAC |

(T)13(G)10 | 90–98 | trnM |

| Satt126 | F:ATAAAACAAATTCGCTGATAT R:GCTTGGTAGCTGTAGGAA |

(ATT)18 | 109–172 | B2 |

| Satt135 | F:TTCCAATACCTCCCAACTAAC R:CACGGATTTTAAATCATTATTACAT |

(ATT)19 | 141–204 | D2 |

| Satt215 | F:GCGCCTTCTTCTGCTAAATCA R:CCCATTCAATTGAGATCCAAAATTAC |

(ATT)11 | 114–221 | J |

| Satt216 | F:TACCCTTAATCACCGGACAA R:AGGGAACTAACACATTTAATCATCA |

(ATT)20 | 137–251 | D1b |

| Satt221 | F:GCGGCAAACCATTATCTTCATT R:GCGATTGTACCACTAAAAACCATAG |

(ATT)23 | 109–224 | D1a |

| Satt231 | F:GGCACGAATCAACATCAAAACTTC R:GCGTGTGCAAAATGTTCATCATCT |

(ATT)32 | 160–328 | E |

| Satt233 | F:AAGCATACTCGTCGTAAC R:GCGGTGCAAAGATATTAGAAA |

(ATT)16 | 169–238 | A2 |

| Satt270 | F:TGTGATGCCCCTTTTCT R:GCGCAGTGCATGGTTTTCTCA |

(ATT)16 | 183–249 | I |

| satt277 | F:GGTGGTGGCGGGTTACTATTACT R:CCACGCTTCAGTTGATTCTTACA |

(ATT)40 | 128–255 | C2 |

| satt288 | F:GCGGGGTGATTTAGTGTTTGACACCT R:GCGCTTATAATTAAGAGCAAAAGAAG |

(ATT)17 | 195–273 | G |

| Satt294 | F:GCGCTCAGTGTGAAAGTTGTTTCTAT R:GCGGGTCAAATGCAAATTATTTTT |

(ATT)23 | 237–303 | C1 |

| Satt373 | F:TCCGCGAGATAAATTCGTAAAAT R:GGCCAGATACCCAAGTTGTACTTGT |

(TAT)21 | 210–279 | L |

| Satt423 | F:TTCGCTTGGGTTCAGTTACTT R:GTTGGGGAATTAAAAAAATG |

(ATT)19 | 225–351 | F |

| Satt463 | F:CTGCAAATTTGATGCACATGTGTCTA R:TTGGATCTCATATTCAAACTTTCAAG |

(ATT)19 | 100–214 | M |

| satt509 | F:GCGCAAGTGGCCAGCTCATCTATT R:GCGCTACCGTGTGGTGGTGTGCTACCT |

(ATT)30 | 119–242 | B1 |

| Satt530 | F:CCAAGCGGGTGAAGAGGTTTTT R:CATGCATATTGACTTCATTATT |

(ATT)12 | 201–279 | N |

| satt555 | F:GCGGTTGGCTTTGATGATGT R:TTACCGCATGTTCTTGGACTA |

(ATT)13 | 234–312 | K |

| Satt568 | F:CGGACACCGGTCTACTAGGAAAGTAA R:GCGGAATAATCCAATTCAATTTA |

(ATT)17 | 212–275 | H |

| satt572 | F:GCGGAGCATGTAAATCCAGCCTATTGA R:GCGGGCTAACTTATGTTACTAAACAAT |

(ATT)14 | 130–241 | A1 |

| satt581 | F:CCAAAGCTGAGCAGCTGATAACT R:CCCTCACTCCTAGATTATTTGTTGT |

(ATT)11 | 130–196 | O |

4.2. Microsatellite Validation and Diversity

Microsatellite data from each population was tested for amplification errors and null alleles, large allele dropout or stuttering using 1000 randomizations in MICROCHECKER v.2.2.3 [58]. Genepop v. 3.4 online [59] was used to check for deviation from Hardy-Weinberg expectations and between loci in each population using exact tests with 10,000 dememorizations, 100 batches and 1000 iterations. Significance level was adjusted using the sequential Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons [60]. For nSSRs, the number of alleles per locus (A), the numbers of different alleles (Na), the observed heterozygosities (HO), expected heterozygosities (HE), fixation index (FIS) and Shannon’s information index (I) were calculated using GenALEx v. 6.4 [61]; allelic richness (AR) was calculated by FSTAT 2.9.3.2 [62]; outcrossing rate (t) was calculated from the fixation index using the equation t = (1 − FIS)/(1 + FIS) [63]. For cpSSR, the number of alleles per locus (A), the numbers of different alleles (Na) and Shannon’s information index (I) were calculated using GenALEx v. 6.4 [61]. In each individual, genetic variants at all cpSSR and nSSR sites were combined into haplotypes. Then, each region was characterized for its plastid DNA diversity using the number of haplotypes detected and gene diversity estimated using the program CONTRIB [64]. Contribution of each region to total diversity (CT) and to total allelic richness (CTR) were calculated according to Petit et al. [65].

4.3. Population Spatial Structure

Genetic differentiation was investigated using the model based clustering method STRUCTURE 2.1 [66,67] for nSSRs. Burn-in time and replication number were set to 100,000 and 100,000 (further generation following the burn in) for each run, respectively. The number of populations (K) in the model was systematically varied from 1 to 10. In order to decrease the margin of error, the average value of 20 simulations performed for each K was used. We used the ΔK method [29] representing the highest median likelihood values to assign wild soybean accessions using the online tool Structure Harvester [68]. For the chosen K value, the run that had the highest likelihood estimate was adopted to assign individuals to clusters. The 10 runs with the lowest DI values for the selected K-value were retained, and their admixture estimates were averaged using CLUMPP v. 1.1.1 [69], applying the greedy algorithm with random input order and 1,000 permutations to align the runs and calculate G’ statistics. Results were visualized using DISTRUCT 1.1 [70].

Nei’s genetic distance (D) and Goldstein’s distance [(δμ)2] are commonly used for microsatellite. Considered Goldstein’s distance (δμ)2 showed bias at small sample sizes and the bias was directly related to the number of alleles and range in allele size [71], a dendrogram based on Nei’s (1978) [72] genetic distance (D) between groups was constructed using the UPGMA method implemented in the PHYLIP v. 3.68 [73]. In order to make sure the results of UPGMA method, a neighbor joining tree also was constructed using PHYLIP v. 3.68. A hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) [74] implemented in Arlequin v. 3.11 [75] was used to partition the observed genetic variation into among clusters, among populations within a cluster and among individuals within a population.

Two commonly estimators of population differentiation are FST, based on allele identity, and RST, which incorporates microsatellite-specific mutation models. We used the allele size permutation test in SPAGeDI [76] to test whether allele sizes were informative in wild soybean microsatellite data set, which would indicate that mutatioin has contributed to differentiation. Because RST was shown to be most appropriate for our data, (see results), the global RST across all samples was calculated in Arlequin v. 3.11 [75]. Gene flow were quantified using the approach of transform estimates of RST into indirect estimates of the average number of migrants exchanged per generation among populations (Nm) [77]. Gene differentiation (RST) was calculated using AMOVA analyses based on population levels, gene flow was estimated from RST (nSSRs: Nm = 0.25(1 − RST)/RST; cpSSRs: Nm = 0.5(1 − RST)/RST).

4.4. Demographic History

We assessed demographic history based on microsatellite data using different and complementary methods. Heterozygosity excess test [78] and mode-shift test [79] from BOTTLENECK 1.2.02 [80] were used to detect the recent population bottleneck. This program conducts tests for recent (within the past 2Ne to 4Ne generations) population bottlenecks that severely reduce effective population size (Ne) and produce an excess in heterozygosity. Heterozygosity excess test was performed under two mutation models: stepwise mutation model (SMM) and two-phase mutation model (TPM). The model of TPM include both 95% single-step mutations and 5% multiple-step mutations, as recommended by Piry [80]. Heterozygosity excess was detected using the one-tailed Wilcoxon sigh-rank test and standardized differences test on 20 nSSR loci [80]. Significance was determined also by the standardized differences and Wilcoxon tests. Mode-shift test detects allele frequency to investigate whether allele frequency distort from the expected L-shaped distribution. During a bottleneck, the loss of rare alleles occurs more rapidly than the associated decrease in expected heterozygosity, as rare alleles do not contribute to HE as much as common alleles, and thus distort the allele frequency distribution from its expected L-shaped distribution [78].

5. Conclusions

In summary, our results show a relatively high level of genetic diversity and genetic differentiation in wild soybean. Two major genetic clusters were revealed by both structure and phylogenetic reconstruction. The MDRY and Korea regions contain the highest genetic diversity, and SWC contributes the most to total diversity and allelic richness. Significant genetic bottlenecks have affected five populations with obvious human disturbance. Based on these results, conversation of wild soybean should reduce habitat loss by human interference, and the SWC region should be conserved with priority.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (project No. is Y01C541211), and the grant of the Talent Project of Yunnan Province (grant No. 2011CI042). This study was conducted in the Key Laboratory of the Southwest China Germplasm Bank of Wild Species, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

References

- 1.Smil V. Magic beans. Nature. 2000;407:567–567. doi: 10.1038/35036653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam H.M., Xu X., Liu X., Chen W.B., Yang G.H., Wong F.L., Li M.W., He W.M., Qin N., Wang B., et al. Resequencing of 31 wild and cultivated soybean genomes identifies patterns of genetic diversity and selection. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1053–1061. doi: 10.1038/ng.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong Y.S., Zhuang B.C., Zhao L.M., Sun H., He M.Y. The genetic diversity of annual wild soybeans grown in China. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001;103:98–103. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li F.S. Studies on the ecological and geographical distribution of the Chinese resources of wild soybean. Sci. Agric. Sin. 1993;26:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu B.R. Conserving biodiversity of soybean gene pool in the biotechnology era. Plant. Species Biol. 2004;19:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin Y., He T.H., Lu B.R. Fine scale genetic structure in a wild soybean (Glycine soja) population and the implications for conservation. New Phytol. 2003;159:513–519. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong Y.S. Advances of research on wild soybean in China. J. Jilin Agric. Univers. 2008;30:394–400. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Y.F. China’s wild plants protection work milestone_National wild plants list for protection (I) Plant J. 1999;5:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K.J., Li X.H., Li F.S. Phenotypic diversity of the big seed type subcollection of wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. et Zucc.) in China. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2008;55:1335–1346. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakamoto S.I., Abe J., Kanazawa A., Shimamoto Y. Marker-assisted analysis for soybean hard seededness with isozyme and simple sequence repeat loci. Breed. Sci. 2004;54:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abe J., Hasegawa A., Fukushi H., Mikami T., Ohara M., Shimamoto Y. Introgression between wild and cultivated soybeans of Japan revealed by RFLP analysis for chloroplast DNAs. Econ. Bot. 1999;53:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimamoto Y., Tozuka A., Fukushi H., Hirata T., Ohara M., Kanazawa A., Mikami T., Abe J. Composite and clinal distribution of Glycine soja in Japan revealed by RFLP analysis of mitochondrial DNA. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1998;96:170–176. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimamoto Y., Fukushi H., Abe J., Kanazawa A., Gai J.Y., Gao Z., Xu D.H. RFLPs of chloroplast and mitochondrial DNA in wild soybean, Glycine soja, growing in China. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 1998;45:433–439. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J.D., Yu J.K., Hwang Y.H., Blake S., So Y.S., Lee G.J., Nguyen H.T., Shannon J.G. Genetic diversity of wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. and Zucc.) accessions from South Korea and other countries. Crop Sci. 2008;48:606–616. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan R.X., Chang R.Z., Li Y.H., Wang L.X., Liu Z.X., Qiu L.J. Genetic diversity comparison between Chinese and Japanese soybeans (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) revealed by nuclear SSRs. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2010;57:229–242. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y.H., Li W., Zhang C., Yang L.A., Chang R.Z., Gaut B.S., Qiu L.J. Genetic diversity in domesticated soybean (Glycine max) and its wild progenitor (Glycine soja) for simple sequence repeat and single-nucleotide polymorphism loci. New Phytol. 2010;188:242–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang M., Li R.Z., Yang W.M., Du W.J. Assessing the genetic diversity of cultivars and wild soybeans using SSR markers. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:4857–4866. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X.H., Wang K.J., Jia J.Z. Genetic diversity and differentiation of Chinese wild soybean germplasm (G. soja Sieb. & Zucc.) in geographical scale revealed by SSR markers. Plant Breed. 2009;128:658–664. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuroda Y., Sato Y.I., Bounphanousay C., Kono Y., Tanaka K. Genetic structure of three Oryza AA genome species (O. rufipogon, O. nivara and O. sativa) as assessed by SSR analysis on the Vientiane Plain of Laos. Conserv. Genet. 2007;8:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuroda Y., Kaga A., Tomooka N., Vaughan D.A. Gene flow and genetic structure of wild soybean (Glycine soja) in Japan. Crop Sci. 2008;48:1071–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuroda Y., Kaga A., Tomooka N., Vaughan D.A. Population genetic structure of Japanese wild soybean (Glycine soja) based on microsatellite variation. Mol. Ecol. 2006;15:959–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshimura Y., Mizuguti A., Matsuo K. Analysis of the seed dispersal patterns of wild soybean as a reference for vegetation management around genetically modified soybean fields. Weed Biol. Manag. 2011;11:210–216. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimamoto Y., Abe J., Gao Z., Gai J.Y., Thseng F.S. Characterizing the cytoplasmic diversity and phyletic relationship of Chinese landraces of soybean, Glycine max, based on RFLPs of chloroplast and mitochondrial DNA. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2000;47:611–617. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen Z.X., Zhao T.J., Ding Y.L., Gai J.Y. Genetic diversity, geographic differentiation and evolutionary relationship among ecotypes of Glycine max and G. soja in China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2009;54:4393–4403. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo J., Wang Y.S., Song C., Zhou J.F., Qiu L.J., Huang H.W., Wang Y. A single origin and moderate bottleneck during domestication of soybean (Glycine max): Implications from microsatellites and nucleotide sequences. Ann. Bot. 2010;106:505–514. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maughan P.J., Maroof M.A.S., Buss G.R. Microsatellite and amplified sequence length polymorphisms in cultivated and wild soybean. Genome. 1995;38:715–723. doi: 10.1139/g95-090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song Q.J., Marek L.F., Shoemaker R.C., Lark K.G., Concibido V.C., Delannay X., Specht J.E., Cregan P.B. A new integrated genetic linkage map of the soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004;109:122–128. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapuis M.P., Estoup A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:621–631. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evanno G., Regnaut S., Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doyle J.J., Morgante M., Tingey S.V., Powell W. Size homoplasy in chloroplast microsatellites of wild perennial relatives of soybean (Glycine subgenus Glycine) Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:215–218. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuroda Y., Tomooka N., Kaga A., Wanigadeva S.M.S.W., Vaughan D. Genetic diversity of wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. et Zucc.) and Japanese cultivated soybeans [G. max (L.) Merr.] based on microsatellite (SSR) analysis and the selection of a core collection. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2009;56:1045–1055. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao R., Xia H., Lu B.R. Fine-scale genetic structure enhances biparental inbreeding by promoting mating events between more related individuals in wild soybean (Glycine soja; Fabaceae) populations. Am. J. Bot. 2009;96:1138–1147. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamrick J.L., Godt M.J.W. Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philos. T. Roy. Soc. B. 1996;351:1291–1298. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo M.C., Yang Z.L., You F.M., Kawahara T., Waines J.G., Dvorak J. The structure of wild and domesticated emmer wheat populations, gene flow between them, and the site of emmer domestication. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007;114:947–959. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozbek O., Millet E., Anikster Y., Arslan O., Feldman M. Spatio-temporal genetic variation in populations of wild emmer wheat, Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides, as revealed by AFLP analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007;115:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0536-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao L.Z. Microsatellite variation within and among populations of Oryza officinalis (Poaceae), an endangered wild rice from China. Mol. Ecol. 2005;14:4287–4297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen Z., Ding Y., Zhao T., Gai J. Genetic diversity and peculiarity of annual wild soybean (G. soja Sieb. et Zucc.) from various eco-regions in China. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009;119:371–381. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powell W., Morgante M., Doyle J.J., McNicol J.W., Tingey S.V., Rafalski A.J. Genepool variation in genus Glycine subgenus Soja revealed by polymorphic nuclear and chloroplast microsatellites. Genetics. 1996;144:792–803. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pakkad G., Ueno S., Yoshimaru H. Genetic diversity and differentiation of Quercus semiserrata Roxb. in northern Thailand revealed by nuclear and chloroplast microsatellite markers. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2008;255:1067–1077. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robledo-Arnuncio J.J., Gil L. Patterns of pollen dispersal in a small population of Pinus sylvestris L. revealed by total-exclusion paternity analysis. Heredity. 2005;94:13–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Setsuko S., Ishida K., Ueno S., Tsumura Y., Tomaru N. Population differentiation and gene flow within a metapopulation of a threatened tree, Magnolia stellata (Magnoliaceae) Am. J. Bot. 2007;94:128–136. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfe K.H., Li W.H., Sharp P.M. Rates of nucleotide substitution vary greatly among plant mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:9054–9058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ebert D., Peakall R. Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs): Technical resources and recommendations for expanding cpSSR discovery and applications to a wide array of plant species. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009;9:673–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holtsford T.P., Ellstrand N.C. Variation in outcrossing rate and population genetic-structure of Clarkia tembloriensis (Onagraceae) Theor. Appl. Genet. 1989;78:480–488. doi: 10.1007/BF00290831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright S. Systems of mating. II. The effects of inbreeding on the genetic composition of a population. Genetics. 1921;6:124–143. doi: 10.1093/genetics/6.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiang Y.T., Chiang Y.C., Kaizuma N. Genetic diversity in natural populations of wild soybean in Iwate prefecture, Japan. J. Hered. 1992;83:325–329. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fujita R., Ohara M., Okazaki K., Shimamoto Y. The extent of natural cross-pollination in wild soybean (Glycine soja) J. Hered. 1997;88:124–128. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volis S., Zaretsky M., Shulgina I. Fine-scale spatial genetic structure in a predominantly selfing plant: Role of seed and pollen dispersal. Heredity. 2010;105:384–393. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li E.X., Qiu Y.X., Yi S., Guo J.T., Comes H.P., Fu C.X. Phylogeography of two East Asian species in Croomia (Stemonaceae) inferred from chloroplast DNA and ISSR fingerprinting variation. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2008;49:702–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qiu Y.X., Sun Y., Zhang X.P., Lee J., Fu C.X., Comes H.P. Molecular phylogeography of East Asian Kirengeshoma (Hydrangeaceae) in relation to Quaternary climate change and landbridge configurations. New Phytol. 2009;183:480–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiu Y.X., Qi X.S., Jin X.F., Tao X.Y., Fu C.X., Naiki A., Comes H.P. Population genetic structure, phylogeography, and demographic history of Platycrater arguta (Hydrangeaceae) endemic to East China and South Japan, inferred from chloroplast DNA sequence variation. Taxon. 2009;58:1226–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qiu Y.X., Fu C.X., Comes H.P. Plant molecular phylogeography in China and adjacent regions: Tracing the genetic imprints of Quaternary climate and environmental change in the world’s most diverse temperate flora. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2011;59:225–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahara H., Sugita S., Harrison S.P., Miyoshi N., Morita Y., Uchiyama T. Pollen-based reconstructions of Japanese biomes at 0, 6000 and 18,000 C-14 yr BP. J. Biogeogr. 2000;27:665–683. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Millien-Parra V., Jaeger J.J. Island biogeography of the Japanese terrestrial mammal assemblages: An example of a relict fauna. J. Biogeogr. 1999;26:959–972. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee J.D., Shannon J.G., Vuong T.D., Nguyen H.T. Inheritance of Salt Tolerance in Wild Soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. and Zucc.) J. Hered. 2009;100:798–801. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doyle J.J., Doyle J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu D.H., Abe J., Gai J.Y., Shimamoto Y. Diversity of chloroplast DNA SSRs in wild and cultivated soybeans: Evidence for multiple origins of cultivated soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002;105:645–653. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-0972-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oosterhout C.V., Hutchinson W.F., Wills D.P.M., Shipley P. micro-checker: Software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2004;4:535–538. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rousset F. GENEPOP’007: A complete re-implementation of the GENEPOP software for Windows and Linux. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008;8:103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rice W.R. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution. 1989;43:223–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peakall R., Smouse P.E. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2006;6:288–295. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goudet J. FSTAT: A computer program to calculate F-statistics. J. Hered. 2002;86:485–486. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weir B.S. Genetic Data Analysis: Methods for Discrete Population Genetic Data. Sinauer Associates, Inc; Sunderland, MA, USA: p. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petit R.J., Excoffier L. Gene flow and species delimitation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009;24:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petit R.J., El Mousadik A., Pons O. Identifying populations for conservation on the basis of genetic markers. Conserv. Biol. 1998;12:844–855. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pritchard J.K., Stephens M., Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Falush D., Stephens M., Pritchard J.K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–1587. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Earl D.A., Vonholdt B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012;4:359–361. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jakobsson M., Rosenberg N.A. CLUMPP: A cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1801–1806. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosenberg N.A. Distruct: A program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2004;4:137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ruzzante D.E. A comparison of several measures of genetic distance and population structure with microsatellite data: Bias and sampling variance. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1998;55:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nei M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics. 1978;89:583–590. doi: 10.1093/genetics/89.3.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Excoffier L., Smouse P.E., Quattro J.M. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: Application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics. 1992;131:479–491. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Excoffier L., Laval G., Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hardy O.J., Vekemans X. SPAGEDi: A versatile computer program to analyse spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2002;2:618–620. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Slatkin M. Rare alleles as indicators of gene flow. Evolution. 1985;39:53–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb04079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cornuet J.M., Luikart G. Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics. 1996;144:2001–2014. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Luikart G., Allendorf F.W., Cornuet J.M., Sherwin W.B. Distortion of allele frequency distributions provides a test for recent population bottlenecks. J. Hered. 1998;89:238–247. doi: 10.1093/jhered/89.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Piry S., Luikart G., Cornuet J.M. BOTTLENECK: A computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective population size using allele frequency data. J. Hered. 1999;90:502–503. [Google Scholar]