Abstract

Sediment, a special realm in aquatic environments, has high microbial diversity. While there are numerous reports about the microbial community in marine sediment, freshwater and intertidal sediment communities have been overlooked. The present study determined millions of Illumina reads for a comparison of bacterial communities in freshwater, intertidal wetland, and marine sediments along Pearl River, China, using a technically consistent approach. Our results show that both taxon richness and evenness were the highest in freshwater sediment, medium in intertidal sediment, and lowest in marine sediment. The high number of sequences allowed the determination of a wide variety of bacterial lineages in all sediments for reliable statistical analyses. Principal component analysis showed that the three types of communities could be well separated from phylum to operational taxonomy unit (OTU) levels, and the OTUs from abundant to rare showed satisfactory resolutions. Statistical analysis (LEfSe) demonstrated that the freshwater sediment was enriched with Acidobacteria, Nitrospira, Verrucomicrobia, Alphaproteobacteria, and Betaproteobacteria. The intertidal sediment had a unique community with diverse primary producers (such as Chloroflexi, Bacillariophyta, Gammaproteobacteria, and Epsilonproteobacteria) as well as saprophytic microbes (such as Actinomycetales, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes). The marine sediment had a higher abundance of Gammaproteobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria, which were mainly involved in sulfate reduction in anaerobic conditions. These results are helpful for a systematic understanding of bacterial communities in natural sediment environments.

INTRODUCTION

Sediment is a special realm in aquatic ecosystems. The biomass and taxon richness of microbes in sediment are much higher than those of the corresponding water bodies (38). Sediment receives deposition of microbes and organic matter from the upper water layer and provides a matrix of complex nutrients and solid surfaces for microbial growth. To understand the potential effects of climate change on microbial biogeochemical cycling, as well as to explore microbial resources, scientists have carried out extensive surveys of the sediment microbial diversity, especially in marine environments like International Census of Marine Microbes (ICoMM) (31, 38). With the recent development of next-generation sequencing methods, unexpectedly diverse bacteria have been recorded in sediments, and the global patterns of bacterial β-diversity in seafloor and seawater ecosystems were revealed for the first time (38).

The intertidal zone is a special environment in marine ecosystems. As a mixing zone between terrestrial and marine habitats, the intertidal sediment is thought to have a significantly different bacterial community than marine sediment (23, 38). For instance, rhizospheric and sediment microbes are thought to be the major biological components that contribute to the productivity of intertidal mangrove ecosystems. Meanwhile, our group and others have isolated a large number of xenobiotic-degrading bacteria from intertidal wetland sediments (33, 35). Nevertheless, microbial ecology studies mainly focus on sulfate-reducing bacteria from Deltaproteobacteria or other limited groups in intertidal sediments (1, 21). Even though deep sequencing studies have been reported recently (4, 7, 15, 24), a detailed comparison of intertidal and marine sediments has not been available.

Compared to marine environments, freshwater sediment has received less attention, despite the fact that fresh water has greater effects on humans (38). It has been reported that the microbial community structure is driven mainly by salinity at the global scale (20). In addition, recent meta-analyses showed that there is a higher bacterial and archaeal diversity in inland freshwater than in marine environments (2, 3). Nevertheless, PCR conditions, sequencing methods, and 16S rRNA short variable regions being sequenced might affect the meta-analysis, particularly for α-diversity, and a reliable comparison should be performed using exactly the same experimental conditions (32, 36).

In the present study, we determined a total of 2.3 million tags from 3 sampling sites of freshwater sediment, intertidal wetland sediment, and marine sediment along the Pearl River in south China and performed a detailed comparison of the bacterial diversity and indicator bacterial groups in each type of sediment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sediment sampling.

A total of 35 samples were collected from the Liu Xi River Reservoir (LXR; freshwater) in Guangzhou (13 samples taken on 1 August 2009), the Mai Po Ramsar wetland (MP; intertidal mudflat and mangrove) (14 samples taken on 3 August 2009), and Yam O Wan (YOW; marine) in Hong Kong (8 samples taken on 2 September 2009). The LXR and MP intertidal sediment samples were taken within a 1-km distance, while the marine sediment samples were within a 5-km distance. The LXR reservoir is located around 200 km upstream of MP and YOW; the distance between MP and YOW is around 20 km. All sediment DNAs were extracted from fresh sediment using the Ultraclean soil DNA isolation kit (MoBio). Physiochemical conditions, including pH, salinity, total organic matter (TOM), total phosphorus (TP), and total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN), were determined as reported previously (19).

PCR amplification.

The PCR amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA V6 tags was performed as described in our previous reports (32, 34). We used the barcode 967F (CNACGCGAAGAACCTTANC) and 1046R (CGACAGCCATGCANCACCT) primers to amplify the bacterial 16S rRNA V6 fragments. The PCR cycle conditions were the following: an initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Each 25-μl reaction mixture consisted of 2.5 μl of TaKaRa 10× Ex Taq buffer (Mg2+ free), 2 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix (2.5 mM each), 1.5 μl of Mg2+ (25 mM each), 0.25 μl of TaKaRa Ex Taq DNA polymerase (2.5 U), 1 μl of template DNA, 0.5 μl of 10 μM barcode primer 967F, 0.5 μl of 10 μM primer 1406R, and 16.75 μl of double-distilled H2O. The barcode-tagged 16S rRNA V6 PCR products were pooled with the other samples and sequenced using Illumina GAII at the Beijing Genomic Institute (Shenzhen, China). The sample was purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The DNA was end repaired, A tailed, and paired-end (PE) adaptor ligated using the paired-end library preparation kit (Illumina). After ligation of the adaptors, the sample was purified and dissolved in 30 μl elution buffer, and 1 μl of the mixture was used as a template for 12 cycles of PCR amplification. The PCR product was gel purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) and sequenced using the 75-bp PE strategy on the Illumina GAII according to the manufacturer's instructions. A base-calling pipeline (Sequencing Control Software, or SCS) was used to process the raw fluorescent images and the call sequences.

Data analysis.

After sequencing, we used the BIPES pipeline to process the raw sequences. Briefly, we used a Perl script to separate the PE reads from each sample according to their barcode sequence in either sequencing file 1 or 2. The PE reads were overlapped to assemble the final V6 tag sequences with the global alignment using the Needleman-Wunsch (NW) algorithm. We removed all of the sequences that contained one or more ambiguous reads (N), those that contained any errors in the forward or reverse primers, and those with more than 1 mismatch within the 40- to 70-bp region during the overlap step. The variable tags (overlapped length minus primers and barcodes) that were shorter than 50 bp or longer than 90 bp were also removed. The clean sequences were screened for chimeras using UCHIME (8).

We used a two-stage clustering (TSC) algorithm to cluster tags into operational taxonomy units (OTUs) (13). Briefly, the tags with frequencies of 3 or greater were clustered using a stringent hierarchical clustering algorithm with the NW distance using the complete linkage method. The rare tags that occurred 1 or 2 times were clustered using a greedy heuristic algorithm with the NW distance using the single linkage. The method clustered highly abundant tags with high accuracy while maintaining the diversity of rare tags and mitigating the effect of sequencing and PCR errors.

The taxonomy assignment of tags and OTUs was performed using the Global Alignment for Sequence Taxonomy (GAST) method (11). The rarefaction curve and Shannon index curve were analyzed using Mothur (29), and statistical analyses for diversity indices and estimators were performed using SPSS13.0. Principal component analysis (PCA) and canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) were performed with Canoco 4.5. LEfSe (30) was used to find indicator bacterial groups specialized within the three types of samples.

Accession numbers.

All of the sequencing data analyzed in the present study can be downloaded from the MG-RAST database using codes 4490041.3 to 4490075.3 and also from our website, http://hwzhoulab.smu.edu.cn/paperdata/.

RESULTS

Sequencing and quality control.

A total of 35 samples were taken from three types of sediments from an upstream freshwater reservoir, a Ramsar intertidal wetland, and marine sediment in Victoria harbor at the Pearl River estuary. These samples were analyzed according to the BIPES pipeline (34). We determined 75 bp from each end of V6 tags using the Illumina GAII. A total of 3,729,248 raw reads corresponding to the exact barcode sequences of the 35 samples were obtained (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). After tag merge and quality control, we obtained a total of 2,318,609 tags. After that, we removed potential chimera tags with UCHIME, and a total of 2,311,761 tags were obtained. We set relatively stringent quality controls, because even though the total number of errors were low, they contributed a large number of rare species and led to overestimation of alpha-diversity, as most of these error sequences were singletons or doubletons (12, 16).

Diversity indices.

Diversity concerns both taxon richness and evenness, and our results demonstrated that both parameters were highest in freshwater sediment and lowest in marine sediment (Fig. 1). To compare the diversity indices, we normalized the sequence number of each sample to 33,309 reads (the fewest among the 35 samples). Tags with 97% similarity (Needleman-Wunsch alignment) then were grouped into OTUs to calculate the rarefaction curves and diversity indices. Rarefaction curves showed that the upstream freshwater sediment had the steepest rarefaction curves with the highest taxon richness, while the marine sediment had the lowest (Fig. 1A). The observed OTU and Chao1 estimator with normalized reads for the three sediments (Fig. 1C) supported the order described above, and there were significant differences between the freshwater and other sediments (P < 0.05). Although we determined tens of thousands of tags per sample, rarefaction curves of OTUs were far from the plateau, indicating that there were more undetermined tags either from real rare species or artificial sequences produced by PCR and sequencing mistakes.

Fig 1.

α-Diversity comparison. Rarefaction curves for OTU (A) and Shannon index (B) were calculated using Mothur (v1.27.0) with reads normalized to 33,307 for each sample using 0.03 distance OTUs.

The Shannon's diversity index considers both richness and evenness. Rarefaction curves of the Shannon index were different from those of the OTUs, as they approached the plateau from less than 10,000 tags per sample (Fig. 1). Both the Shannon's diversity index value at a sequencing depth of 33,307 and its rarefaction curves showed that the freshwater sediment had the highest diversity, ranging from 7.63 to 8.03, while the marine sediment had the lowest, ranging from 6.53 to 6.95, and there were significant differences (P < 0.05) among the three groups (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). In brief, our results suggested that the freshwater sediment had the highest bacterial richness and evenness and the marine sediment had the lowest.

Table 1.

Diversity indices used in this studya

| Sample type (n) | Diversity index |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTU | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | |

| Freshwater (13) | 8,331 | 16,545* | 24,128 | 7.84* |

| Intertidal (14) | 6,761 | 14,439* | 22,112 | 7.26* |

| Marine (8) | 6,059 | 13,297* | 20,825 | 6.76* |

An asterisk indicates values with significant differences (P < 0.05).

Phylum-level taxonomic distribution.

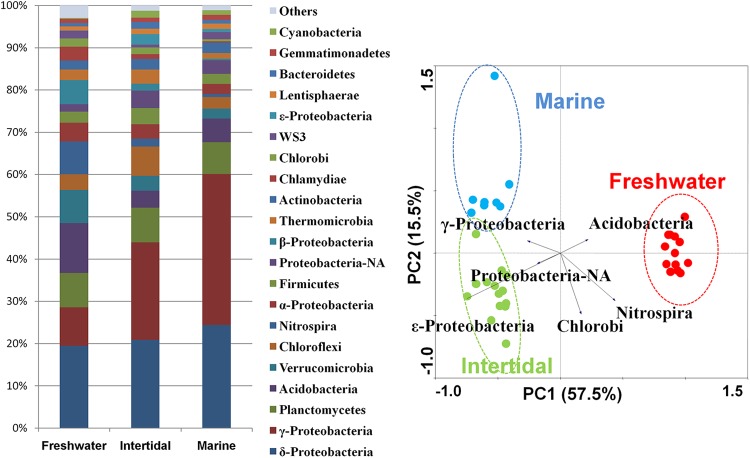

We assigned the taxonomy of all tags using the GAST method, the pipeline of which showed a high performance for analyzing the V6 tag (11). We included the proteobacteria classes in the phylum-level analysis because proteobacteria represented more than 60% of all phyla in marine samples, and including its classes could provide more detailed information (Fig. 2A). Tags that were assigned to the Proteobacteria phylum but that could not be further assigned into any of the specific proteobacterial classes were put into a Proteobacteria-NA group. All three types of sediments harbored diverse lineages of bacterial phyla; a total of 48 phyla (or proteobacterial classes) were determined in the freshwater, 47 in the intertidal wetland, and 47 in the marine sediments. Deltaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Planctomycetes, Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, Verrucomicrobia, Nitrospira, Alphaproteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria-NA were the 10 most abundant groups (from first to tenth) in total.

Fig 2.

Phylum distribution. (Left) Relative abundance of the dominant bacterial phyla in the three types of sediments. (Right) Principal component analysis (PCA) of phylum abundance data using Canoco 4.5.

The community in the freshwater sediment was the most evenly distributed, while marine sediment was the most biased, with a dominance of Gammaproteobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria, a trend that was in concordance with that of the α-diversity result (Fig. 2A). PCA demonstrated that the three types of communities could be separated using the phylum abundance data set (Fig. 2B), indicating that these three sediments had significantly different bacterial phyla. Specifically, three proteobacterial groups (Gammaproteobacteria, Epsilonproteobacteria, and Proteobacteria-NA) were enriched in the marine and intertidal sediments, while Acidobacteria and Nitrospira were more abundant in freshwater sediment according to the PCA result.

Genus-level distribution.

The top 10 most abundant genera differed among the three sediments (Table 2). The intertidal wetland sediment acted as a transition between the other two, an observation similar to those of the phylum results. The intertidal wetland sediment community shared 3 of its top 10 genera (Nitrospira, Planctomyces, and Pirellula) with the freshwater sediment community and four (Desulfobacterium, Planctomyces, Desulfobulbus, and Caldithrix) with the marine sediment community. Only Planctomyces was shared by all three.

Table 2.

Genus/Acidobacteria subdivision abundance in the three types of sediments

| Abundance rank | Genus/Acidobacteria subdivision by source |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater | Intertidal | Marine | |

| 1 | Magnetobacterium | Sulfurovum | Gp10 |

| 2 | Nitrospira | Desulfobacterium | Gp22 |

| 3 | Gp6 | Nitrospira | Planctomyces |

| 4 | Planctomyces | Desulfuromonas | Rubritalea |

| 5 | Pirellula | Planctomyces | Cycloclasticus |

| 6 | Gp1 | Rhabdochromatium | Pelobacter |

| 7 | Gp3 | Desulfobulbus | Desulfobulbus |

| 8 | Gemmatimonas | Pirellula | Desulfobacterium |

| 9 | Coxiella | Desulfosarcina | Acinetobacter |

| 10 | Syntrophus | Caldithrix | Caldithrix |

We used CCA to discern the genus-level structure using the physiochemical parameters. Samples from each type of sediment clustered more tightly at the genus level than at the phylum level, especially for the freshwater and marine sediments, so the three groups had much clearer separation (Fig. 3). The five analyzed environmental variables (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) were included in the CCA biplot. The first axis, which was negatively correlated with all five variables, explained 47.8% of the microbial diversity observed, while the second axis explained 16.5% of the variation. The salinity explained the difference between the freshwater sediment and the other two, while three factors associated with high nutrient concentration (TOM, TKN, and TP) were related to the specific bacterial community living in the intertidal wetland (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) diagram illustrating the relationship between the genus-level community structure from different sampling sites and environmental variables.

OTU-level analysis.

When assigning taxonomy for short variable 16S rRNA gene tags using GAST or RDP Classifier, many tags could only be assigned to a relatively coarse taxonomy level. Therefore, a number of sequences were excluded from the fine taxonomy data analysis. After normalization, there were a total of 1,165,745 tags assigned to the 35 samples. The number was reduced to 1,094,779 tags at the phylum level, and only 349,890 tags were analyzed at the genus level. As fewer sequences might lead to decreased resolution, we utilized all sequences for statistical analysis by clustering sequences into OTUs (97%).

The 1,165,745 tags were clustered into 70,432 OTUs using TSC. The pipeline utilized the average linkage for clustering tags with an abundance of 3 or higher and a single linkage for linking singleton and doubleton tags, a step which reduced the inflation of OTUs caused by rare tags (13). Not surprisingly, the OTU-level data produced the highest resolution for differentiating the three types of sediment bacterial communities, and each group of sediment samples clustered together with relatively high similarity (Fig. 4). The clustering result also indicated that groups of intertidal and marine sediment communities were more similar to each other than to freshwater sediment. In addition, from the most abundant (abundance higher than 0.1%) to the rarest (2 reads in all 35 samples) OTUs, bacterial communities from each sediment type grouped tightly, and the three types could be separated clearly (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), indicating that bacterial communities from the most dominant to the rarest were selected by their habitats.

Fig 4.

Clustering of samples. Bray-Curis similarity index was calculated using the abundance of OTUs, and hierarchical clustering was calculated using average linkage algorithms using PRIMER 6. F means freshwater samples, I means intertidal samples, and M means marine samples.

Bacterial groups with statistical differences.

In addition to α- and β-diversities, another major aim in comparing microbial communities is to find specialized bacterial groups within each type of sample. Recently, Segata et al. developed a tool called LEfSe, which is suitable for statistical analysis of metagenomic data from two or more microbial communities (30). This method was designed to analyze data where the number of species is much higher than the number of samples and to provide biological class explanations to establish statistical significance, biological consistency, and effect-size estimation of predicted biomarkers (30). This tool can analyze bacterial community data at any taxonomy level. However, because analyzing the large number of OTUs determined in the present study was too computationally intensive, we only performed statistical analysis from domain to genus levels.

A total of 635 bacterial groups were distinct to at least one sediment using the default logarithmic (LDA) value of 2 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Cladograms show taxa with LDA values higher than 3.5 for clarity (Fig. 5 and 6); the LDA value for each lineage is listed in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. There were 8 groups of bacteria enriched in freshwater sediment, namely, Acidobacteria (from phylum to family), Chlamydiae (from phylum to order), Nitrospira (from phylum to genus), Alphaproteobacteria (the class and its orders Rhizobiales and Rhodospirillales), Betaproteobacteria (the class and orders of Burkholderiales and Rhodocyclales), Myxococcales and Syntrophaceae (within Deltaproteobacteria), Legionellales and Methylococcaceae (within Gammaproteobacteria), and Verrucomicrobia (from phylum to order). Within these, 7 fine lineages had an LDA value of 4 or higher, namely, Acidobacteriaceae, Chlamydiales, Magnetobacterium, Nitrospira, Burkholderiales, Syntrophaceae, and Verrucomicrobiales (Fig. 6).

Fig 5.

Cladogram indicating the phylogenetic distribution of microbial lineages associated with the three types of sediments; lineages with LDA values of 3.5 or higher determined by LEfSe are displayed. Differences are represented in the color of the most abundant class (red indicating freshwater, green intertidal, purple marine, and yellow nonsignificant). Each circle's diameter is proportional to the taxon's abundance. The strategy of multiclass analysis is nonstrict (at least one class differential). Circles represent phylogenetic levels from domain to genus inside out. Labels are shown of the phylum and class levels.

Fig 6.

Indicator microbial groups within the three types of sediments with LDA values higher than 4.

The bacterial lineages enriched in the intertidal wetland were Actinomycetales, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, Epsilonproteobacteria, Rhodobacterales (an order within Alphaproteobacteria), and Ectothiorhodospiraceae (a family within Gammaproteobacteria), as shown in Fig. 5 and 6. Only Anaerolineae, Desulfobacteraceae, Ectothiorhodospiraceae, and three groups in Epsilonproteobacteria (Campylobacterales, Helicobacteraceae, and Sulfurovum) showed LDA values higher than 4 in intertidal wetland sediment (Fig. 6; also see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

The Proteobacteria phylum was enriched in the marine sediment (Fig. 5 and 6), particularly the Gammaproteobacteria and two orders in Deltaproteobacteria (Desulfobacterales and Desulfuromonadales). At fine taxonomy levels, the marine sediment only had Desulfobulbaceae, Desulfuromonadaceae, and Chromatiales showing LDA values higher than 4 (Fig. 5 and 6; also see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

The organelle group.

Although the present study was designed to determine the bacterial diversity, the 967F/1046R primer set used in the present study amplified a small number of sequences assigned to Archaea (49 tags) and organelles (26,000 tags). Similar findings have been described in previous studies (9). LEfSe showed that three organelle lineages from Cyanobacteria and Bacillariophyta were enriched in the intertidal wetland with LDA values higher than 3.5 (Fig. 5; also see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

The present study provides a detailed experimental comparison of bacterial communities in three different sediments. Within our determined samples, the freshwater environment showed the highest bacterial richness and diversity, while the marine sediment was the lowest among the three, even though marine sediment is known to have high bacterial diversity. These data were consistent with recent meta-analysis results showing that both bacterial and archaeal communities in inland freshwater have higher levels of diversity than those of saline waters (2, 3). Our study is the first comparison of diversity estimators using exactly the same experimental conditions, which is critical for taxon richness estimators. In our results, the Chao1 of freshwater sediment was significantly higher than that of the other two sites. The exact Chao1 and ACE estimators are biased at this time. In the first report of determining microbial diversity using pyrosequencing, researchers found an unexpectedly large bacterial diversity in marine sediment (31). Shortly thereafter, it was realized that sequencing errors introduced by the pyrosequencing contributed a large fraction of so-called rare species and that richness estimators were extremely sensitive to the error-prone sequences (25, 27). Even though we used the Illumina instrument with stringent quality controls to determine the tag sequences, there are still many biases introduced by PCR error, sequencing error, sequencing depth, and the bioinformatic pipeline (10, 12, 26, 32, 36). Most of these biases, e.g., PCR mutation and chimera, cause overestimation of richness, while primer mismatching and others lead to underestimation. Therefore, even with high-throughput sequencing, we cannot directly compare the taxon richness in our present results to those obtained using different protocols, nor can we state that the ever-increasing rarefaction curves of OTUs reflected a mixture of real diversity of rare taxa and not experimental biases.

Contrary to richness estimators, the Shannon's diversity index is much less sensitive to sequencing and PCR errors. The Shannon's diversity index is H′ = − Σi=1R pi log(pi), in which pi is the proportion of individuals belonging to the ith species in the data set of interest. It could be deduced from the formula that tags at low frequencies either from undetermined rare species or from experimental errors contribute little to the Shannon index, because the pi value for rare tags is normally less than 10−3 for high-throughput sequencing results (12, 16, 32, 38). In our results, all rarefaction curves of the Shannon index approached the plateau phase with more than 30,000 sequences per sample, indicating that these values were saturated without the need to determine more sequences, and the Shannon index was less sensitive to the experimental conditions of PCR and sequencing platforms. The Shannon indices of the three types of sediments determined in the present study were comparable to those recently reported using pyrosequencing methods, even though different protocols were employed. For example, the Shannon index was 6.7 to 7.1 for sediment in a German drinking water reservoir (28), 5.6 to 6.5 for sediment in a Brazil mangrove wetland (7), and 6.7 in a coral reef (6). We should note that, in the present study, the 0.03 distance OTU was used to estimate the diversity, which might cause an inflated estimation. Even though the 0.03 distance is a tradition for clustering 16S rRNA tags, different variable regions might have different appropriate distances, which is still an unsettled problem.

With the help of high sequence numbers, the present study determined diverse lineages, and almost all common phyla were observed in each type of sediment. As the most diverse and even community, the freshwater sediment had the highest number of indicator taxa distributed in a variety of lineages, of which Acidobacteria, Nitrospira, and Verrucomicrobia were the three major indicators (Fig. 5 and 6). Acidobacteria are ubiquitous and abundant members of soil bacterial communities with a few described strains (14), but their role in freshwater sediment has not been well documented (22). Many studies suggest that the abundance of the Acidobacteria phylum is significantly correlated with pH, and more specifically that its abundance increases when the pH is lower than 5.5 (14, 17). However, acidic pH is not the reason for accumulation of Acidobacteria in freshwater sediment, because recent studies of freshwater sediments in Germany and Spain also reported that the abundance of the Acidobacteria phylum ranged from 4 to 6%, which is similar to our result, and none of these samples were acidic (28, 37). Although the Acidobacteria phylum accumulated in the freshwater sediment, not all subdivisions of the phylum were the same. Our result and recent reports suggest that subdivision 6 (Gp6), Gp1, Gp3, Gp4, and Gp18 (from high to low confidence) are enriched in the freshwater environment while subdivisions Gp10, Gp22, Gp21, and Gp26 are more abundant in marine sediments (23). These results indicate that Acidobacteria are relatively abundant in sediment environments; more cultivation studies would be helpful for understanding their ecological roles. In addition to Acidobacteria, Nitrospira is another strong indicator. Both the first (Magnetobacterium) and second (Nitrospira) most abundant genera in freshwater sediment were from Nitrospirae (Table 1). The phylum is one of the key players in the nitrogen cycle but is a less intensively studied group of nitrite oxidizing bacteria (NOB).

Proteobacteria was the most abundant and largest phylum in all three sediments, but its classes showed different tendencies. Within the phylum, Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria were enriched in the freshwater sediment, Gammaproteobacteria in marine sediment, Epsilonproteobacteria in intertidal wetland, and Deltaproteobacteria in all sediments. The wide distribution of Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria in freshwater environments has been well documented, and pH and nutrients have been explained to be related to their abundances (22). In comparison, the bacterial groups enriched in marine sediment were mainly limited to the Gammaproteobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria (Fig. 5 and 6), and almost all of them were involved in sulfur reduction.

The intertidal wetland showed a unique pattern of bacterial diversity compared to that of freshwater or marine sediments. The pattern was concordant with recent reports about bacterial communities in a Brazilian mangrove and Korean intertidal sediments (7, 15). According to our analysis, the unique microbial community in intertidal sediment was correlated with its high primary productivity and sulfur cycling. A large number of photoautotrophic microbes, e.g., Chloroflexi, Bacillariophyta, and Ectothiorhodospiraceae (from the order of Chromatiales) were significantly enriched in intertidal environments (Fig. 5 and 6). In addition, many chemolithoautotrophic bacteria from Epsilonproteobacteria were also enriched in intertidal sediment, such as Sulfurovum and Arcobacter (Campylobacterales). It has been reported that Epsilonproteobacteria occur in high abundance at oxic-anoxic interfaces such as where the marine sediment surface meets oxygenated seawater (5), and our study suggests that the intertidal sediment is another typical interface. Additionally, a recent study reported that novel groups of Gammaproteobacteria accounted for 40 to 70% of CO2 fixation using sulfur as the electron donor in a coastal intertidal sediment (18). Our study also showed high abundance of OTUs from unclassified Gammaproteobacteria within the intertidal sediment, and the tag sequence of these OTUs showed a relatively high similarity (>95%) with the groups described in the report mentioned above. All of these results suggest that the intertidal sediment is highly productive and has various types of primary producers which contribute to the high nutrient concentration in the intertidal environment. It is rational to deduce that a high primary production supports diverse consumers, and many saprophytic microbes preferring eutrophic conditions, such as Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Actinomycetales, were enriched in the intertidal wetland accordingly. This special community structure provided a clue to isolate microbes with biodegradation potential from intertidal sediment, even though many strains had been obtained without clear prior knowledge.

In conclusion, microbial communities from three different habitats showed obvious differences, which could not be fully explained by the limited factors determined in the present study. However, the present study provided a detailed comparison of three types of sediments using the same high-throughput sequencing method. The freshwater sediment had the highest diversity, with Acidobacteria, Nitrospira, Verrucomicrobia, Alphaproteobacteria, and Betaproteobacteria as indicators. The intertidal sediment had medium diversity, with many primary producers (such as Chloroflexi, Bacillariophyta, Gammaproteobacteria, and Epsilonproteobacteria) and eutrophic microbes (such as Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Actinomycetales). The marine sediment had the lowest diversity and was enriched with Gammaproteobacteria and some Deltaproteobacteria orders, which were mainly involved with sulfate reduction under anaerobic conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 31270152), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in Universities (NCET-11-0921), the Ph.D. Programs Foundation of the Education Ministry of China (no. 20094433120017), the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (no. S2011010004136), and the COMRA project (DY125-15-R-01).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 September 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Antje G, Marc M, Henrik S, Heribert C, Martin K. 2008. Identity and abundance of active sulfate-reducing bacteria in deep tidal flat sediments determined by directed cultivation and CARD-FISH analysis. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2645–2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Auguet JC, Barberan A, Casamayor EO. 2010. Global ecological patterns in uncultured archaea. ISME J. 4:182–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barberan A, Casamayor EO. 2010. Global phylogenetic community structure and beta-diversity patterns in surface bacterioplankton metacommunities. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 59:1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bolhuis H, Stal LJ. 2011. Analysis of bacterial and archaeal diversity in coastal microbial mats using massive parallel 16S rRNA gene tag sequencing. ISME J. 5:1701–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell BJ, Engel AS, Porter ML, Takai K. 2006. The versatile ε-proteobacteria: key players in sulphidic habitats. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:458–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen CP, Tseng CH, Chen CA, Tang SL. 2011. The dynamics of microbial partnerships in the coral Isopora palifera. ISME J. 5:728–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. dos Santos HF, et al. 2011. Mangrove bacterial diversity and the impact of oil contamination revealed by pyrosequencing: bacterial proxies for oil pollution. PLoS One 6:e16943 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edgar RC. 2010. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26:2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Finkel OM, Burch AY, Lindow SE, Post AF, Belkin S. 2011. Geographical location determines the population structure in phyllosphere microbial communities of a salt-excreting desert tree. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:7647–7655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huber JA, et al. 2009. Effect of PCR amplicon size on assessments of clone library microbial diversity and community structure. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1292–1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huse SM, et al. 2008. Exploring microbial diversity and taxonomy using SSU rRNA hypervariable tag sequencing. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000255 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huse SM, Welch DM, Morrison HG, Sogin ML. 2010. Ironing out the wrinkles in the rare biosphere through improved OTU clustering. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1889–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang XT, et al. 2012. Two-stage-clustering (TSC): a pipeline for selecting operational taxonomic units for the high-throughput sequencing of PCR amplicons. PLoS One 7:e30230 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones RT, et al. 2009. A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses. ISME J. 3:442–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim BS, et al. 2008. Rapid phylogenetic dissection of prokaryotic community structure in tidal flat using pyrosequencing. J. Microbiol. 46:357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kunin V, Engelbrektson A, Ochman H, Hugenholtz P. 2010. Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Environ. Microbiol. 12:118–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N. 2009. Soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale: a pyrosequencing-based assessment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5111–5120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lenk S, et al. 2011. Novel groups of gammaproteobacteria catalyse sulfur oxidation and carbon fixation in a coastal, intertidal sediment. Environ. Microbiol. 13:758–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li CH, Zhou HW, Wong YS, Tam NFY. 2009. Vertical distribution and anaerobic biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mangrove sediments in Hong Kong, South China. Sci. Tot. Environ. 407:5772–5779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lozupone CA, Knight R. 2007. Global patterns in bacterial diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:11436–11440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mussmann M, Ishii K, Rabus R, Amann R. 2005. Diversity and vertical distribution of cultured and uncultured Deltaproteobacteria in an intertidal mud flat of the Wadden Sea. Environ. Microbiol. 7:405–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Newton RJ, Jones SE, Eiler A, McMahon KD, Bertilsson S. 2011. A guide to the natural history of freshwater lake bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75:14–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Orcutt BN, Sylvan JB, Knab NJ, Edwards KJ. 2011. Microbial ecology of the dark ocean above, at, and below the seafloor. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75:361–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pires ACC, et al. 2012. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and barcoded pyrosequencing reveal unprecedented archaeal diversity in mangrove sediment and rhizosphere samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:5520–5528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Quince C, et al. 2009. Accurate determination of microbial diversity from 454 pyrosequencing data. Nat. Methods 6:639–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quince C, Lanzen A, Davenport R, Turnbaugh P. 2011. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinformatics 12:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reeder J, Knight R. 2009. The ‘rare biosphere’: a reality check. Nat. Methods 6:636–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roske K, Sachse R, Scheerer C, Roske I. 2012. Microbial diversity and composition of the sediment in the drinking water reservoir Saidenbach (Saxonia, Germany). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 35:35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schloss PD, et al. 2009. Introducing mothur: open source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7537–7541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Segata N, et al. 2011. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12:R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sogin ML, et al. 2006. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored “rare biosphere.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12115–12120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu JY, et al. 2010. Effects of polymerase, template dilution and cycle number on PCR based 16S rRNA diversity analysis using the deep sequencing method. BMC Microbiol. 10:255 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-10-255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou HW, Guo CL, Wong YS, Tam NFY. 2006. Genetic diversity of dioxygenase genes in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degrading bacteria isolated from mangrove sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 262:148–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou HW, et al. 2011. BIPES, a cost-effective high-throughput method for assessing microbial diversity. ISME J. 5:741–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhou HW, Luan TG, Zou F, Tam NFY. 2008. Different bacterial groups for biodegradation of three-and four-ring PAHs isolated from a Hong Kong mangrove sediment. J. Hazard. Mater. 152:1179–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou J, et al. 2011. Reproducibility and quantitation of amplicon sequencing-based detection. ISME J. 5:1303–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zimmermann J, Portillo MC, Serrano L, Ludwig W, Gonzalez JM. 2012. Acidobacteria in freshwater ponds at Donana National Park, Spain. Microb. Ecol. 63:844–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zinger L, et al. 2011. Global patterns of bacterial beta-diversity in seafloor and seawater ecosystems. PLoS One 6:e24570 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.