Abstract

Urinary bladder smooth muscle contraction is triggered by parasympathetic nerves, which release ATP and acetylcholine (ACh) that bind to purinergic and muscarinic receptors, respectively. Neuronal signalling may thus elicit myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) phosphorylation and contraction through the combined, but distinct contributions of these receptors. Both receptors mediate Ca2+ influx whereas muscarinic receptors may also recruit Ca2+-sensitization mechanisms. Using transgenic mice expressing calmodulin sensor myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) in smooth muscles, the effects of suramin/α,β-methyleneATP (α,β-meATP) (purinergic inhibition) or atropine (muscarinic inhibition) on neurally stimulated elevation of [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation, force and phosphorylation of RLC, myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) targeting subunit MYPT1 and MLCP inhibitor protein CPI-17 were examined. Electric field stimulation (EFS) increased [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation and concomitant force in a frequency-dependent manner. The dependence of force on [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation decreased with time suggesting increased Ca2+ sensitization in the late contractile phase. RLC and CPI-17 phosphorylation increased upon stimulation with maximal responses at 20 Hz; both responses were attenuated by atropine, but only RLC phosphorylation was inhibited by suramin/α,β-meATP. Antagonism of purinergic receptors suppressed maximal MLCK activation to a greater extent in the early contractile phase than in the late contractile phase; atropine had the opposite effect. A frequency- and time-dependent increase in MLCK phosphorylation explained the desensitization of MLCK to Ca2+, since MLCK activation declined more rapidly than [Ca2+]i. EFS elicited little or no effect on MYPT1 Thr696 or 850 phosphorylation. Thus, purinergic Ca2+ signals provide the initial activation of MLCK with muscarinic receptors supporting sustained responses. Activation of muscarinic receptors recruits CPI-17, but not MYPT1-mediated Ca2+ sensitization. Furthermore, nerve-released ACh also initiates signalling cascades leading to phosphorylation-dependent desensitization of MLCK.

Key points

Parasympathetic nerves release the neurotransmitters ATP and acetylcholine that activate purinergic and muscarinic receptors, respectively, to initiate contraction of urinary bladder smooth muscle.

Although both receptors mediate Ca2+ influx for myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) phosphorylation necessary for contraction, the muscarinic receptor may also recruit cellular mechanisms affecting the Ca2+ sensitivity of RLC phosphorylation.

Using transgenic mice expressing Ca2+/calmodulin sensor myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) in smooth muscles, the effects of selective purinergic or muscarinic receptor inhibition were examined on neurally stimulated tissues in relation to signalling pathways converging on RLC phosphorylation.

Purinergic-mediated Ca2+ signals provide the initial Ca2+/calmodulin activation of MLCK with muscarinic receptors supporting sustained responses.

Activation of muscarinic receptors leads phosphorylation of myosin light chain phosphatase inhibitor CPR-17 to enhance Ca2+ sensitivity while also initiating phosphorylation-dependent Ca2+ desensitization of MLCK. The interplay between Ca2+ sensitization and desensitization mechanisms fine tunes the contractile signalling module for force development.

Introduction

Contraction of murine urinary bladder smooth muscle (UBSM) to void urine is triggered by the action of ATP and acetylcholine (ACh), which are co-released from parasympathetic nerve varicosities (Fry et al. 2010). Significant progress has been made toward understanding the electrophysiological mechanisms underlying neurogenic UBSM contraction; however, relatively little is known about downstream signalling to contractile proteins by reversible phosphorylation. The simultaneous release of ATP and ACh results in Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels affected by both the ionotropic P2X1 receptor, a non-selective ligand-gated cation channel, and by the metabotropic, G-protein-coupled muscarinic receptor, mAChR, respectively (Andersson & Arner, 2004). Although precise details of the coupling between mAChR and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels remain to be clarified, several lines of evidence, including use of Ca2+ channel blockers and knockout of the channel's pore-forming subunit, CaV1.2, have documented the dependence of cholinergic contractions upon Ca2+ influx through the channel (Schneider et al. 2004b; Wegener et al. 2004; Nausch et al. 2010). Studies on UBSM from transgenic mice showed that high frequency neural stimulation leads to rapid increases in global [Ca2+]i, myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) activation and myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) phosphorylation that temporally precede force development over a few seconds, illustrating tightly coupled Ca2+ signalling for contraction (Ding et al. 2009). Not revealed in these first few seconds were potentially slower, phosphorylation-dependent steps that could modulate Ca2+ sensitivity of contractile proteins during neurogenic contractions.

Increases in [Ca2+]i and changes in Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus are two major regulatory mechanisms for smooth muscle contraction. The former activates Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent MLCK that phosphorylates RLC at Ser19 to increase actin-activated myosin ATPase and thus force generation (Kamm & Stull, 1985; Horowitz et al. 1996; Stull et al. 1996; Kamm & Stull, 2001), whereas the latter mainly involves the inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP), which can occur either directly by Rho kinase-catalysed phosphorylation of the myosin-targeting subunit of MLCP (MYPT1) or indirectly via phosphorylation of a protein kinase C (PKC)-potentiated protein phosphatase 1 inhibitor protein of 17 kDa (CPI-17) (Somlyo & Somlyo, 2003; Puetz et al. 2009). Inhibition of MLCP leads to increased RLC phosphorylation at a given [Ca2+]i, thus bringing about Ca2+ sensitization. A confounding interpretation of sensitization mechanisms involving MLCP is that Ca2+/CaM activation of MLCK may be desensitized by MLCK phosphorylation within the CaM-binding sequence (Kamm & Stull, 2001; Ding et al. 2009). The extent to which modulatory signalling pathways involving Ca2+ sensitization and desensitization participate during the course of neurogenic bladder contraction is not known. In the present study, we evaluated effects of both frequency and time after neural stimulation to delineate the relationships among [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation, and force, thus defining conditions under which sensitization or desensitization occur. Measures of regulatory protein phosphorylation were used to delimit mechanisms.

Neuronal signalling in mouse bladder is predominated at low frequencies by ATP signalling and at high frequencies by ACh (Werner et al. 2007). The ATP-evoked, rapid contraction is mediated primarily via the ionotropic P2X1 receptor, a non-selective ligand-gated cation channel (Hashitani et al. 2000; Vial & Evans, 2000; Young et al. 2008). On the other hand, the slower, metabotropic response to ACh in urinary bladder is mediated by activating G-protein-coupled muscarinic receptor subtype M3 (Hegde et al. 1997; Matsui et al. 2000; Abrams et al. 2006). The canonical downstream event initiated by Gq-coupled muscarinic receptors is activation of phospholipase C (PLC) with subsequent generation of InsP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG) to induce Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum and activate PKC, respectively (Felder, 1995; Caulfield & Birdsall, 1998). Although both neurotransmitters cause smooth muscle contraction by inducing Ca2+ transients as elementary signals in the process of nerve–smooth muscle communication (Hashitani et al. 2000; Heppner et al. 2005), muscarinic agonists also activate cellular pathways leading to increased Ca2+ sensitivity of the myofilaments (Kishii et al. 1992; Takahashi et al. 2004; Teixeira et al. 2007; Mizuno et al. 2008). In the present study, we used purinergic and muscarinic antagonists to investigate the contributions of these signalling pathways.

Previously, we constructed a Ca2+/CaM-dependent MLCK ‘biosensor’ molecule and expressed it specifically in the smooth muscle cells of transgenic mice (Geguchadze et al. 2004; Isotani et al. 2004). This CaM-sensor MLCK is capable of directly monitoring Ca2+/CaM binding and activation of the kinase, where Ca2+-dependent CaM binding increases kinase activity coincident with an increase in the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) ratio. Using this CaM-sensor MLCK, we have performed real-time measurements of MLCK activation by Ca2+/CaM in response to receptor agonists and membrane depolarization with simultaneous measurement of force, and revealed that agonist-induced contraction results from Ca2+ sensitization with phosphorylation of CPI-17 and MYPT1 as well as Ca2+/CaM-dependent activation of MLCK (Isotani et al. 2004; Mizuno et al. 2008). Moreover, temporal studies demonstrated that EFS-evoked initial contraction of mouse UBSM (50 Hz, 3 s train duration) is strictly dependent on the rapid increase in [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation, and RLC phosphorylation without any apparent involvement of the Rho kinase- or PKC-mediated Ca2+ sensitization (Ding et al. 2009). The present study was undertaken to further functionally characterize the temporal profile of purinergic and muscarinic cell signalling during nerve-stimulated UBSM contraction. Specifically, we focused on [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation, RLC phosphorylation and force development. In addition, recruitment of Ca2+ sensitization (indexed by MYPT1 and CPI-17 phosphorylation) was also examined. We have examined the hypothesis that Ca2+ sensitization is recruited with prolonged nerve stimulation and at greater frequencies where the muscarinic component of the force response becomes prominent.

Methods

Ethical approval

The experiments were performed in accordance with NIH and Institutional Animal Care and Use Guidelines. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center approved all procedures and protocols. All protocols and procedures are in compliance with The Journal of Physiology guidelines (Drummond, 2009).

Isolation of detrusor smooth muscle for isometric force measurements

Maintained wild-type or CaM sensor transgenic ICR mice were killed with a lethal i.p. injection of Avertin. The urinary bladder was removed and placed in physiological salt solution (PSS) in mm: 118.5 NaCl, 4.75 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 24.9 NaHCO3, 1.6 CaCl2, 10.0 d-glucose, aerated with 95% O2–5% CO2 to maintain pH at 7.4, at 37°C). After dissecting away the urothelium layer, four longitudinal strips of the detrusor muscle were prepared per bladder and mounted in a water-jacketed 8 ml organ bath for isometric force recording. Muscle strips were adjusted to a length for optimal tension development, and allowed to equilibrate for 60 min before experiments began. To test the viability of smooth muscle cells, muscle strips were contracted with 65 mm KCl twice. Strips having a contractile response less than 0.8 g were discarded. Nerve-mediated UBSM contractions were elicited by electric field stimulation (EFS) using a pair of electrodes mounted in the tissue bath in parallel to the UBSM strip. Pulses of 0.5 ms duration were delivered in trains at increasing frequencies (0.5–80 Hz) by a DC power amplifier (HP 6824A) driven by a Grass S88 stimulator at 20 V. Contractions in response to KCl and EFS were measured using Grass FT03 force transducers, with the outputs recorded on a Powerlab 8/SP data acquisition unit (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). After the first frequency–response curve was generated, UBSM strips were washed three times and allowed to rest for 20–30 min. Subsequently, muscle strips were incubated with no inhibitors, suramin/α,β-methylene ATP (α,β-meATP) (10 μm each) or atropine (1 μm) for 20 min to elucidate the relative contributions of purinergic and muscarinic signalling to the contraction. Then, a second frequency–response curve to EFS was generated using the same EFS parameters as before. Time-matched control tissues were treated similarly to the test tissues, but were exposed to the normal bathing solution instead of inhibitors. Maximal responses obtained at 50 Hz before application of inhibitors were used as a reference value for normalizing subsequent contractile responses.

Simultaneous measurement of contraction and CaM sensor MLCK FRET ratio or [Ca2+]i

Simultaneous measurements of force and FRET ratio or [Ca2+]i were performed as previously described (Isotani et al. 2004). Briefly, bladder tissues were dissected into small strips (0.5 mm × 0.5 mm × 8.0 mm), mounted, and stretched (1.2 × slack length) on a force transducer in a quartz cuvette (180 μl) for simultaneous force and fluorescence measurements in PSS. For FRET measurements the muscle strips were illuminated with an excitation wavelength of 430 nm, and emission intensity was detected by two photomultipliers using 480 and 525 nm filters. The extent of MLCK activation was determined from the 480/525 nm emission ratio (FRET ratio). FRET ratio and force measurements were recorded on a Powerlab 8/SP data acquisition unit (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Strips were first stimulated with 65 mm KCl to test viability, and then the frequency–response of the CaM sensor MLCK FRET was determined. Twenty minutes later, the strip was treated with either muscarinic or purinergic inhibitors for another 20 min and the frequency–response was measured again in the continued presence of inhibitors.

Global intracellular calcium concentrations were measured by Indo-1 fluorescence ratio in wild-type bladder strips as described previously (Isotani et al. 2004). Urothelium-denuded bladder smooth muscle strips were incubated in the dark with PSS containing 10 μm Indo-1 AM, 0.01% pluronic F-127, and 0.02% cremophor for 4 h at room temperature. After incubation, tissues were mounted in the fluorescence myograph and washed with fresh PSS for 30 min at 36°C. Strips were illuminated at 365 nm and emission intensities were measured at 405 nm and 485 nm to obtain an emission ratio of 405 nm to 485 nm. Strips were stimulated with the same protocol as for FRET measurements. Muscle tension and fluorescence ratios F480/F525 and F405/F485 in the resting state were taken as 0%, and the values for percentage contraction, F480/F525 and F405/F485 were calculated by taking the maximal responses to 50 Hz before inhibitor treatment as 100%.

Preparation of electrically stimulated bladder smooth muscle strips for biochemical measurements

Muscle strips were prepared and mounted in an organ bath as described above for isometric force measurement. To allow continuous field stimulation of the strip between the time the organ bath was lowered and the tissue was frozen, fine silver wire was attached directly to both ends of the tissue (Ding et al. 2009). Following initial treatments with 65 mm KCl, bladder strips were relaxed in PSS for 30 min, and then stimulated electrically for 10 s at 10, 20 and 50 Hz before being snap-frozen with a clamp pre-chilled in liquid nitrogen. In another set of experiments, strips were treated with the muscarinic inhibitor atropine (1 μm) or purinergic inhibitors suramin and α,β-meATP (10 μm each). Twenty minutes later, EFS at 20 Hz was applied and muscle strips were rapidly frozen at designated times. Frozen tissues were stored at −80°C until they were added to a frozen slurry of acetone in 10% trichloroacetic acid, slowly thawed, and homogenized in 10% trichloroacetic acid and 10 mm DTT. Samples were centrifuged at 800 × g for 3 min to process for protein phosphorylation measurements. Protein content was determined by a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Measurement of RLC phosphorylation

RLC phosphorylation was measured by urea/glycerol-PAGE as previously described (Colburn et al. 1988). Briefly, muscle proteins precipitated in 10% trichloroacetic acid and 10 mm DTT were solubilized in 8 m urea sample buffer and subjected to urea/glycerol-PAGE at 400 V for 90 min to separate non-phosphorylated and monophosphorylated protein forms. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against smooth muscle RLC. The ratio of mono-phosphorylated RLC to total RLC (non-phosphorylated plus mono-phosphorylated) was quantified by densitometry.

Western blot analysis of MYPT-1, CPI-17, MLCK and protein kinase D (PKD) phosphorylation

Tissue extracts prepared in urea sample buffer were added to 0.2 volumes of SDS sample buffer containing 250 mm Tris (pH 6.8), 10% SDS, 50 mm DTT, 40% glycerol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue, boiled and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred electrophoretically onto nitrocellulose membranes. After being blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with phosphospecific anti-MYPT1Thr696 (1:6000, Upstate), anti-MYPT1Thr850 antibody (1:4000, Upstate), anti-CPI-17Thr38 antibody (1:500, Santa Cruz), anti-MLCKSer1760 antibody (1:7500, ProSci) or anti-PKDSer916 (1:1000, Cell Signaling). The blots were washed and incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1.5 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL Plus Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare). Membranes were then stripped of bound antibodies by incubation in a buffer containing 62.5 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS and 10 mm DTT for 30 min at 55°C with gentle agitation. The blots were reprobed with anti-MYPT1 (1:5000, BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-CPI-17 (1:5000), anti-MLCK (1:10,000) or anti-PKD (1:1000 Cell Signaling) for loading controls. The images were acquired with a STORM 840 scanner (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and the signal intensity was quantified by densitometry using ImageQuant 5.2 software (Molecular Dynamics). The extent of protein phosphorylation was expressed as the ratio of the density of the bands corresponding to the phosphorylated proteins to the bands corresponding to total proteins.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± SEM. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test or two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test was used. Linear and non-linear regressions were performed to compare best-fit parameters between pairs of curves by Student's t test assuming a Gaussian distribution. Student's paired, two-tailed t test was used for comparison between control and treatment group. Data analyses were carried out using statistical software (Prism 5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Frequency–response for [Ca2+]i, MLCK biosensor fluorescence and isometric force in UBSM with neural stimulation

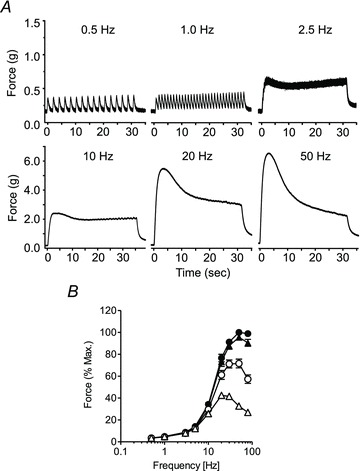

To characterize the contractile activity of UBSM in response to intramural nerve stimulation, we first determined the frequency–response relationship of EFS-evoked contractions. Figure 1A shows the typical profile of force generated by field stimulation at 0.5, 1, 2.5, 10, 20 and 50 Hz. Figure 1B illustrates summarized data showing the time dependence of force at different frequencies of transmural nerve stimulation. At higher frequencies (≥20 Hz) UBSM generated a rapid phasic contraction reaching a maximal response within 5 s and declining to a value 20–40% of the maximal force by 30 s. However, the prominent transient component evident at higher frequencies is largely absent at intermediate frequencies (2.5 and 10 Hz).

Figure 1. Frequency- and time-dependence of isometric force development in electrically stimulated mouse UBSM.

A, representative contractile response to EFS (0.5–50 Hz). B, quantitative summary of frequency-dependent contractile responses at maximal response (•), 5 s (▴), 10 s (○) and 30 s (△). Force was normalized to the maximal force obtained at 50 Hz. Data are mean ± SEM for muscle strips from eight animals. Error bars smaller than symbols are not shown.

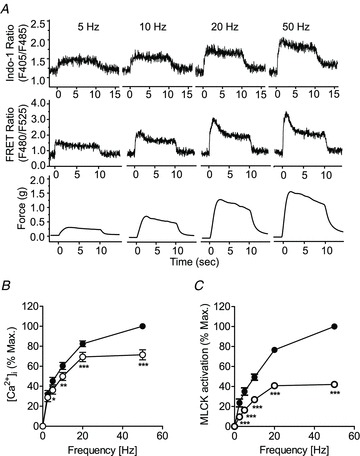

We also simultaneously measured [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation in response to neural stimulation in bladder strips to obtain real-time and quantitative information relative to simultaneous contractile responses. Note that the changes in FRET for MLCK measure binding of Ca2+/CaM which causes activation, whereas kinase activity per se would be measured by RLC phosphorylation. EFS causes a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i (Indo-1 ratio) and MLCK activation (FRET ratio) (Fig. 2A). Similar to the force tracing, MLCK biosensor responses to EFS were biphasic in nature, and particularly evident at high stimulation frequencies (≥20 Hz). However, Ca2+ responses to EFS showed only a slight decrement over time, instead maintaining relatively stable values during field stimulation. Normalized data show the dependence of [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation on the frequency of transmural nerve stimulation (Fig. 2B and C). It is clear from these plots that while the frequency-dependent increase in maximal [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation were similar, MLCK activation declined to a greater extent compared with [Ca2+]i at 10 s. This may suggest a time-dependent decrease in the affinity of MLCK for Ca2+/CaM.

Figure 2. Frequency- and time-dependence of isometric force development, MLCK activation and [Ca2+]i in electrically stimulated UBSM.

A, representative traces show the frequency dependence of Indo-1 fluorescence ratio ([Ca2+]i), CaM-biosensor MLCK FRET ratio (MLCK activation) and isometric force development following neural stimulation in UBSM strips. B and C, quantitative summary of the Indo-1 fluorescence for [Ca2+]i (B), and CaM-biosensor MLCK FRET ratio for MLCK activation (C), at maximal response (•),and 10 s (○). Maximal values obtained at 50 Hz were taken as 100%. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from 14–15 measurements each from a different bladder.

Dependence of force on [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation

To gain further insights into whether nerve-activated UBSM contractile force involves changes in Ca2+ sensitivity, we plotted force as a function of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3A) or MLCK activation (Fig. 3B) using the data from experiments shown in Fig. 2. Although modest in appearance, analyses of the Ca2+ dependence of force (Fig. 3A) reveals a significant difference between maximal and 10 s relations, suggesting that force is sensitized to Ca2+ with time. The apparent small extent of Ca2+ sensitization may result from a combination of desensitization of MLCK to Ca2+ and sensitization of force to MLCK activation via inhibition of MLCP activity. Results in Fig. 3B show that the relation between force and MLCK activation shifted to the left with time, that is, after 10 s equal force required less MLCK activation. These relations suggest that the process of sensitization of force to [Ca2+]i and the extent of MLCK activation occurs during the sustained phase of contraction. Thus, while sensitization of force to [Ca2+]i appears to be modest in extent below 50 Hz, sensitization to MLCK activation is apparent at all frequencies examined. As observed in Fig. 2, there was a greater decline in MLCK activation than in [Ca2+]i fluorescence ratio between early maximal responses and 10 s, implying desensitization of MLCK to Ca2+/CaM activation. Consistent with this, when the MLCK activation was plotted as a function of [Ca2+]i at the early maximal responses and 10 s, linear regression analysis revealed the two slopes to be significantly different (0.99 ± 0.03 and 0.61 ± 0.02, P < 0.001), demonstrating that MLCK becomes desensitized to Ca2+ with time (Fig. 3C). Together, these data indicate that both Ca2+ sensitization and desensitization mechanisms are elicited during transmural nerve stimulation of UBSM.

Figure 3. Quantitative relationships with force development, [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation.

Dependence of force on [Ca2+]i (A), or MLCK activation (B). C, dependence of MLCK activation on [Ca2+]i. UBSM strips were electrically stimulated at 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 50 Hz. For each data set, values increase in order with 2.5 Hz the lowest and 50 Hz the highest. Values were calculated at maximal responses (•) and 10 s (○) and normalized to the maximal response obtained at 50 Hz. Values are from experiments shown in Fig. 2 and expressed as mean ± SEM. Data in A and B were fitted with a non-linear model. Best fit parameters differed significantly (P < 0.001) between peak and 10 s curves in each panel. Data in panel C were fitted by linear regression. Slopes of peak and 10 s values differed significantly (P < 0.001).

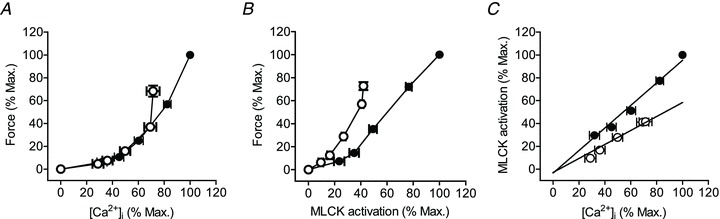

Frequency–response for phosphorylation of RLC, MYPT1 and CPI-17 in UBSM with neural stimulation

RLC phosphorylation is required to initiate smooth muscle contraction, and is determined by the balance of MLCK and MLCP activities (Kamm & Stull, 2001; Somlyo & Somlyo, 2003; He et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2010). Extensive studies of various smooth muscles have provided convincing evidence that inhibition of MLCP via phosphorylation of MYPT1 and/or CPI-17 plays an important role in modulating RLC phosphorylation and Ca2+ sensitization of contraction, but differences are noted in different kinds of smooth muscles (Kitazawa et al. 2003; Somlyo & Somlyo, 2003). To test the hypothesis that Ca2+ sensitization is recruited at higher nerve firing frequencies with EFS, we determined the phosphorylation profiles of RLC, MYPT1 and CPI-17 in nerve-stimulated UBSM. As shown in Fig. 4A, RLC phosphorylation was 0.10±0.02 mol phosphate per mol RLC (n = 5) at rest and increased rapidly and significantly with EFS. No RLC di-phosphorylation was detected in field-stimulated UBSM. CPI-17 phosphorylation was also low at rest and dramatically increased 7- to 9-fold following nerve stimulation for 10 s (Fig. 4D). MYPT1 Thr850 phosphorylation increased slightly following EFS and only achieved significance at 50 Hz of field stimulation when compared with resting values. MYPT1 Thr696 phosphorylation did not increase with nerve stimulation at any frequency tested (Fig. 4B). However, treatment of UBSM with 10 μm carbachol increased MYPT1 Thr696 and Thr850 phosphorylation 96% and 150%, respectively (data not shown), similar to previous results (Mizuno et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2009). Collectively, these data show that EFS contracts UBSM in a frequency-dependent manner and dramatically increases RLC and CPI-17 phosphorylation with little or no effect on MYPT1 Thr696 or Thr850 phosphorylation. Thus, intramural nerve stimulation recruits the Ca2+ sensitization mechanism mainly via the CPI-17 pathway.

Figure 4. Frequency–responses for RLC (A), MYPT1 (B and C), CPI-17 (D), MLCK (E) and PKD (F) phosphorylation in mouse UBSM.

Representative Western blots are shown above each densitometric result. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from 5 animals in each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. resting value as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

MLCK desensitization during nerve stimulation-evoked UBSM contraction

The apparent desensitization of MLCK activity to [Ca2+]i seen in Fig. 3C, could result from phosphorylation of S1760 in the CaM-binding domain that decreases the affinity of MLCK for Ca2+/CaM (Kamm & Stull, 2001; Ding et al. 2009). Western blotting with a phospho-site-specific antibody for pSer1760 showed that nerve stimulation increased phosphorylation in a frequency-dependent manner, as illustrated in Fig. 4E. Thus, the decrease in MLCK activation during sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i in neurally stimulated UBSM probably results from phosphorylation of S1760.

Frequency-dependent phosphorylation of PKD in nerve stimulation-evoked UBSM contraction

Protein kinase D (PKD) is a novel serine/threonine protein kinase, in the PKC superfamily. PKD activation is generally attributed to phosphorylation by PKC, and like members of the PKC family, DAG is required for PKD function (Wang, 2006; Fu & Rubin, 2011). Once activated, PKD is autophosphorylated at Ser916, and this site is used as a marker to study the regulation of PKD activity in vivo (Matthews et al. 1999). Recently, PKD has been implicated in the regulation of channels involved in Ca2+ handling, including the voltage-dependent calcium channel, CaV1.2 (Streets et al. 2010; Aita et al. 2011). To test the possibility that neural stimulation activates PKD in UBSM, we measured PKD phosphorylation at Ser916. Figure 4F shows a frequency-dependent increase in PKD phosphorylation, suggesting that it is activated upon neural stimulation.

Temporal contributions of purinergic and muscarinic signalling for [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation during neurally stimulated contraction

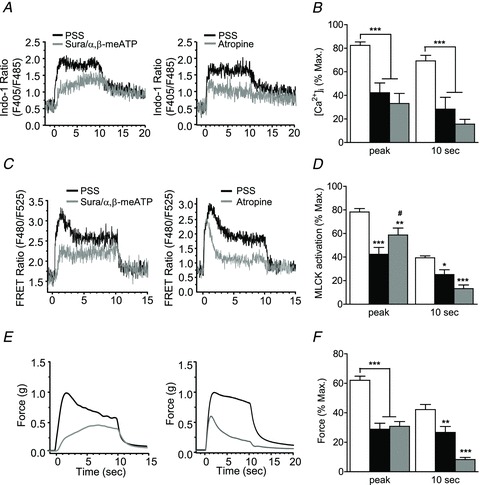

To elucidate the temporal contributions of ATP- and ACh-mediated signalling in [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation responses to EFS, stimulus was applied at 20 Hz for 10 s, and [Ca2+]i and MLCK FRET fluorescence ratios were measured in UBSM strips pre-treated with suramin/α,β-meATP (10 μm each) or atropine (1 μm) for 20 min. We chose a frequency of 20 Hz based on muscle contraction responses to this stimulus parameter that were atropine- and suramin/α,β-meATP sensitive, and of sufficient amplitude to visualize changes in contraction, [Ca2+]i and MLCK FRET ratio. In addition, RLC and CPI-17 phosphorylation reached maximal responses at this stimulation frequency. Figure 5 shows measurements of [Ca2+]i, MLCK FRET and force before and after inhibitor treatment. Suramin/α,β-meATP and atropine treatment exhibit similar effects on suppressing [Ca2+]i elevation during the time course of EFS-evoked contraction (Fig. 5B). In general, blockade of purinergic or muscarinic transmission caused 50–60% or 60–80% decrease in EFS-induced [Ca2+]i responses, respectively. Inactivation of the purinergic pathway by suramin/α,β-meATP also markedly suppressed EFS-evoked MLCK activation with the initial contractile phase inhibited more (50%) than the late sustained phase (35%). In contrast, inhibition of muscarinic signalling by atropine decreased tonic MLCK activation to a greater extent (55–70%) than the initial peak phase (25%, Fig. 5D). Inhibition of either receptor suppressed maximal force responses to a similar extent, while atropine reduced the tonic force more than that of suramin/α,β-meATP, particularly evident at 10 s (Fig. 5E and F). Interestingly, purinergic inhibition with suramin/α,β-meATP significantly slowed the rate of increase in contractile force to EFS (Fig. 5E). The combination of atropine and suramin/α,β-meATP virtually abolished the nerve-evoked contraction (data not shown), as previously reported (Werner et al. 2007; Ding et al. 2009; Streets et al. 2010; Aita et al. 2011). These results suggest that the purinergic component may be dominant for MLCK activation in the initial phase of contraction, while the muscarinic component is prominent in the sustained phase.

Figure 5. Effects of purinergic and muscarinic inhibitors on [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation in neurally stimulated UBSM.

A, C and E, representative traces showing the effects of suramin/α,β-meATP and atropine on Indo-1 fluorescence ratio, MLCK FRET ratio and isometric force following neural stimulation at 20 Hz in UBSM strips. B, D and F, quantitative summary of the effects of suramin/α,β-meATP (black bars) and atropine (grey bars) on the time course of [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation and force responses following neural stimulation at 20 Hz at different times. Values are normalized to the maximal response obtained at 50 Hz without inhibitor treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with vehicle (open bars) at the same time points. #P < 0.05 compared with suramin/α,β-meATP at peak, as determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons. Data are mean ± SEM from at least 7 determinations.

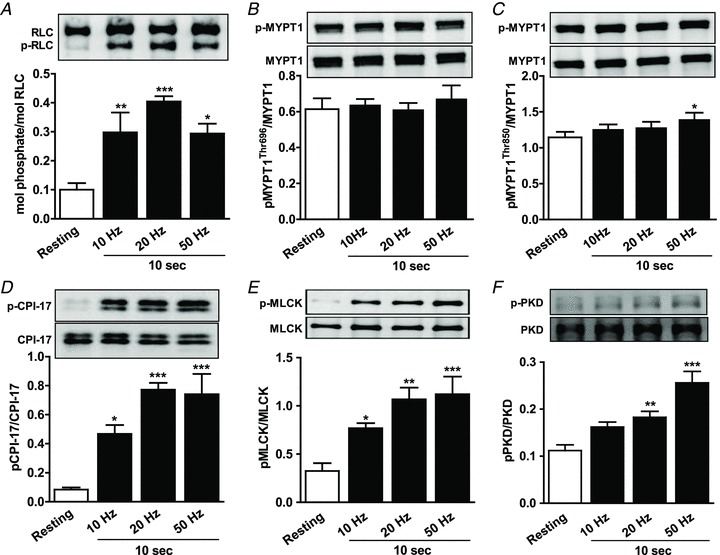

The relative contributions of purinergic and muscarinic pathways for RLC, CPI-17, MLCK and PKD phosphorylation in neurally stimulated UBSM

To gain further insights into the mechanisms underlying nerve-activated UBSM contraction, we used a pharmacological approach to specifically characterize the signalling pathways elicited by each of the parasympathetic co-transmitters ATP and ACh. UBSM strips were pre-treated for 20 min with either purinergic or muscarinic blockers before stimulation at 20 Hz. Western blotting analysis of the time course of protein phosphorylation revealed that RLC phosphorylation increased from 0.06 mole phosphate per mol RLC at rest to 0.04 mol phosphate per mol RLC at 5 s and then declined to a steady-state level at 10 and 30 s of about 0.30 mol phosphate per mol RLC (Fig. 6A). CPI-17 phosphorylation showed a similar pattern, where nerve stimulation caused a rapid increase in CPI-17 phosphorylation which lasted for 10 s and then declined at 30 s (Fig. 6B). Atropine treatment partially suppressed EFS-induced RLC and CPI-17 phosphorylation. When compared to the vehicle group, atropine significantly decreased phosphorylation of RLC at 5 s and CPI-17 at 5 and 10 s. Purinergic inhibition with suramin/α,β-meATP only attenuated RLC phosphorylation at 5 s without any effect on CPI-17 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A and B). As mentioned above, EFS failed to increase MYPT1 phosphorylation, so the effects of inhibitors were not examined. All together, these findings are consistent with a model where the purinergic pathway initiates Ca2+ influx to activate MLCK and RLC phosphorylation while the muscarinic pathway recruits Ca2+ sensitization via CPI-17 phosphorylation in addition to Ca2+ mobilization.

Figure 6. Effects of purinergic and muscarinic inhibitors on EFS-induced RLC (A), CPI-17 (B), MLCK (C) and PKD (D) phosphorylation at different times.

UBSM strips were preincubated with vehicle (open bars), suramin/α,β-meATP (10 μm each; black bars) or atropine (1 μm; grey bars) for 20 min, and then rapidly frozen at 5, 10 and 30 s following EFS at 20 Hz. The frozen tissues were processed for RLC, CPI-17, MLCK and PKD phosphorylation measurement as described under Methods. Values are means ± SEM from 4–9 determinations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment at the same time points. ##P < 0.01 compared with suramin/α,β-meATP at 5 s as determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni for multiple comparisons.

Having established the desensitization of MLCK with EFS (Figs 3C and 4E), we next investigated the roles of ACh and ATP transmission in this event. Nerve stimulation at 20 Hz caused a time-dependent increase in MLCK phosphorylation over 30 s (Fig. 6C vehicle group, P < 0.001, n = 6). Inhibition of purinergic transmission did not affect MLCK phosphorylation during neurally stimulated UBSM contraction, whereas blockade of the muscarinic pathway by atropine significantly reduced MLCK phosphorylation (Fig. 6C). Thus, nerve-released ACh, but not ATP initiates a cascade leading to the desensitization of MLCK to Ca2+ during neurogenic contraction. Similarly, PKD showed a time-dependent increase in phosphorylation over 30 s of EFS at 20 Hz. While purinergic blockade had no effect on PKD phosphorylation, atropine resulted in a significant reduction at 30 s (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

The present study was designed to investigate the elementary intracellular signalling mechanisms evoked by ACh and ATP upon transmural nerve stimulation-elicited contraction of UBSM. Field stimulation of parasympathetic nerves in the bladder wall elicits rapid, frequency-dependent contractions that are maximal at 50 Hz. Inhibition of muscarinic receptors by atropine and purinoceptors by suramin/α,β-meATP reduced contractile responses at all the frequencies tested. Our results showing that EFS-elicited contractions are mediated by ACh and ATP release are consistent with published data wherein mouse UBSM contraction is dependent on purinergic and muscarinic signalling, the former dominant at low frequencies (<10 Hz), while the latter are effective at higher frequencies (≥20 Hz) (Brading & Williams, 1990; Werner et al. 2007).

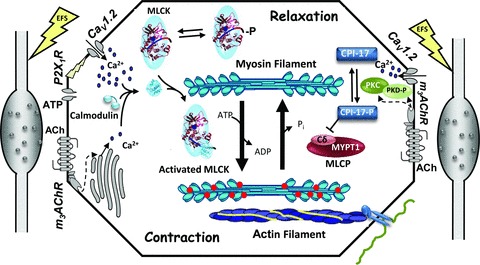

Mouse UBSM responds to EFS with frequency-dependent increases in global [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2) and this rise in [Ca2+]i precedes force development (Ding et al. 2009). As shown by others, both muscarinic and purinergic receptor signalling elicit Ca2+ influx that supports contraction in UBSM. Mice with Cav1.2 L-type Ca2+ channel deficiency in smooth muscle cells exhibited markedly reduced detrusor contraction in response to the muscarinic agonist carbachol (Wegener et al. 2004). Other investigators have demonstrated that L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitors attenuated muscarinic-receptor-mediated detrusor contraction in many species examined (Zderic et al. 1994; Schneider et al. 2004a,b; Wuest et al. 2007). Electrophysiological studies revealed that contractions induced by nerve-released ACh also depend on Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent calcium channels but not InsP3-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release (Nausch et al. 2010). In addition, membrane excitability and the amplitude of [Ca2+]i response and associated contraction following purinoceptors activation by neurally released ATP were blunted by L-type Ca2+ channel blockers (Hashitani et al. 2000). Collectively, this evidence indicates that Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent calcium channels plays an important role in normal bladder contraction (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Scheme depicting signalling processes with neural stimulation in urinary bladder smooth muscle.

Electric field stimulation of UBSM strips releases ATP and ACh from parasympathetic nerve varicosities in the tissue, represented on either side of the smooth muscle cell scheme. ATP binding to the P2X1R purinergic receptor causes depolarization and thus opening of the voltage-gated calcium channel, Cav1.2, leading to a large calcium influx. ACh binding to the m3AChR leads to PLC-mediated increases in InsP3 and DAG. InsP3 (dashed arrow at left) initiates release of a smaller amount of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. DAG (dashed arrows at right) participates in the activation of PKC and PKD. Muscarinic signalling also leads to activation of the voltage-gated calcium channel by mechanisms that are not well defined, but may involve PKD phosphorylation and activation (right side). Cytosolic calcium binds to calmodulin, which then activates MLCK for phosphorylation of the myosin RLC. Phosphorylated myosin interacts with actin in thin filaments leading to force development or shortening through actin filaments anchored indirectly to the extracellular matrix. Myosin dephosphorylation, and thus relaxation, is brought about by MLCP, containing a catalytic subunit (Cδ) and myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1 (MYPT1). MLCP can be inhibited by a CPI-17 in its phosphorylated form (CPI-17-P). MLCK is also phosphorylated resulting in desensitization to Ca2+/CaM binding and activation. In the current study, electric field stimulation led to significant increases in phosphorylation of myosin RLC (red circles on myosin filament), as well as CPI-17, PKD and MLCK (indicated by -P). The significance of these phosphorylations is discussed in the text.

Ca2+/CaM-dependent MLCK is necessary to initiate and maintain smooth muscle contraction (He et al. 2008, 2011; Zhang et al. 2010). Knockout of MLCK selectively in smooth muscle tissues eliminates smooth muscle contractile responses to G-protein-coupled receptor activation in addition to depolarization with KCl. However, maximal contractile responses do not require maximal activation of MLCK (Isotani et al. 2004; Mizuno et al. 2008). Although MLCK is necessary for smooth muscle contraction, only a fraction (30%) of the kinase is activated due to limiting free Ca2+/CaM, but this amount is sufficient for robust RLC phosphorylation leading to maximal force development (Fig. 7).

Electric field stimulation results in activation of Ca2+/CaM-dependent MLCK that, like [Ca2+]i, precedes force development. Our previous study demonstrated that high-frequency nerve stimulation triggers Ca2+ signalling as an elementary mechanism to initiate contraction of UBSM within a second (Ding et al. 2009). Increases in [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation and RLC phosphorylation were tightly coupled and preceded force development. We extend these findings to test the hypothesis that Ca2+ sensitization is recruited with prolonged stimulation and at greater EFS frequencies where the muscarinic component of the force response becomes prominent (Heppner et al. 2009).

In the presence of the purinoceptor inhibitor suramin/α,β-meATP, the initial phasic components of [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation and force were almost abolished. Purinergic inhibition also significantly delayed the time to reach the maximal response (data not shown). This is similar to results of others where purinergic signalling is rapid and contributes significantly to the initial phasic component of the EFS-evoked contraction (Brading & Mostwin, 1989; Lamont et al. 2003; Heppner et al. 2005, 2009). Blockade of the muscarinic pathway with atropine also caused a reduction in the maximal [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation and force responses; however, the later sustained phase was suppressed to a greater extent. Nerve-released ATP and ACh may differentially shape the UBSM contraction with ATP triggering a signal to initiate contraction while ACh dominates for the maintenance of force. However, there is significant temporal overlap in signalling processes initiated by the two receptor systems.

Many studies, including our own, have shown that activation of muscarinic receptors by bath-applied, high concentrations of agonist increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus in a ROCK- and protein kinase C-dependent manner in UBSM (Fleichman et al. 2004; Takahashi et al. 2004; Durlu-Kandilci & Brading, 2006; Teixeira et al. 2007; Mizuno et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2009). It is not known, however, how these results relate to signalling by intramural nerve stimulation during UBSM contraction. Here, we provide evidence that CPI-17 phosphorylation increased with frequency of stimulation, and was sustained during the time course of nerve-mediated contraction. Moreover, CPI-17 phosphorylation was suppressed by muscarinic, but not purinergic inhibition. These results are consistent with a model where parasympathetic release of ACh signals through muscarinic receptors to cause CPI-17 phosphorylation, most likely by PKC, thus leading to inhibition of MLCP under physiological conditions of UBSM contraction (Fig. 7).

Protein kinase D is also a substrate of PKC and requires DAG for activity (Wang, 2006; Fu & Rubin, 2011), thus PKD may be activated by muscarinic signalling in UBSM. Intriguingly, although ACh acts through muscarinic receptors to activate both PLC and phospholipase D (PLD) in UBSM, contractions are diminished by inhibitors of PLD, but not PLC (Schneider et al. 2004b; Frei et al. 2009; Huster et al. 2010; Nausch et al. 2010). Recent findings suggest that a signalling complex consisting of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel, PKC and PLD plays a significant role in controlling muscarinic-mediated contractions of UBSM (Huster et al. 2010). PLD activity can be stimulated by muscarinic receptors leading to increases in cellular phosphatidic acid by hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine (Rumenapp et al. 2001). Phosphatidic acid is further degraded into DAG by phosphohydrolases, and DAG produced by PLD via phosphatidic acid is capable of activating PKD (Kam & Exton, 2004). Recently, Maturana and colleagues reported that PKD regulates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels through phosphorylation of the pore-forming subunit CaV1.2 (Aita et al. 2011). We found a frequency-dependent increase in phosphorylation of the PKD autophosphorylation site, and like CPI-17, autophosphorylation was inhibited by muscarinic, but not purinergic blockers. PKD may thus play a role in muscarinic signalling for Ca2+ influx in USBM.

In contrast to results obtained with CPI-17, our data did not support a role for MYPT1 phosphorylation in mediating Ca2+ sensitization of the contractile response evoked by EFS. We observed a small increase in phosphorylation of MYPT1-Thr850 at 50 Hz, which is consistent with previous data (Ding et al. 2009). Under resting conditions, MYPT1 is phosphorylated at both Thr696 and Thr850. Thus, a constitutively active ROCK may contribute to basal MYPT1 phosphorylation in mouse bladder smooth muscle as evidenced by other studies (Hashitani et al. 2004; Poley et al. 2008). We earlier provided evidence showing differences in sensitivity of MYPT1 and CPI-17 phosphorylation to stimulation by carbachol (Mizuno et al. 2008). At low agonist concentrations, only CPI-17 was phosphorylated, with MYPT1 phosphorylation recruited as the carbachol concentration was increased. One possibility may be that the amount of neurally released ACh acting on muscarinic receptors of UBSM is not sufficiently high to evoke increases in MYPT1 phosphorylation.

Secondary signalling processes to MLCK are imposed on MLCK Ca2+/CaM activation and MLCP inhibition by CPI-17 phosphorylation. Changes in MLCK activation were not always proportional to increases in [Ca2+]i. At longer times after initiation of a contractile response, MLCK activation becomes desensitized to Ca2+, consistent with phosphorylation at S1760. Phosphorylation of this site in the C-terminus of MLCK's CaM binding domain decreases the affinity of the kinase for Ca2+/CaM (Stull et al. 1990, 1993; Kamm & Stull, 2001). As observed in this study, nerve stimulation caused a frequency- and time-dependent increase in MLCK phosphorylation. The phosphorylation was shown previously to be Ca2+ dependent; however, the identity of the MLCK kinase has not been clearly established (Stull et al. 1990; Tansey et al. 1992; Rokolya & Singer, 2000). Recently, Horman and colleagues provided evidence that AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylates MLCK in the CaM binding domain resulting in desensitization of MLCK (Horman et al. 2008). It is unlikely that the concentration of AMP increases sufficiently in neurally stimulated UBSM to directly activate AMPK; however, alternative activation of AMPK by Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase kinase β could be involved (Merlin et al. 2010). Interestingly, our data show that atropine, but not suramin/α,β-meATP, partially suppressed nerve stimulation-elicited MLCK phosphorylation despite both muscarinic and purinergic pathways causing increased [Ca2+]i. This result is in part consistent with previous findings suggesting that MLCK is dephosphorylated by MLCP in smooth muscle (Nomura et al. 1992; Tang et al. 1993). Inhibition of MLCP via muscarinic signalling would augment MLCK phosphorylation at comparable [Ca2+]i, as seen with these inhibitors. Further studies are required to identify the kinase responsible for MLCK desensitization in response to intramural nerve stimulation.

In summary, physiological stimulation of UBSM by release of neurotransmitters ATP and ACh rapidly increases [Ca2+]i, MLCK activation and RLC phosphorylation (Fig. 7). Muscarinic and purinergic components influence different phases of these signalling modules. Purinoceptor-mediated Ca2+ influx provides the initial signal to trigger MLCK activation with muscarinic receptors supporting sustained Ca2+ influx. Moreover, activation of muscarinic receptors recruits CPI-17-mediated, but not MYPT1-mediated MLCP inhibition to increase RLC phosphorylation and thus contraction. In addition to Ca2+ sensitization, nerve-released ACh also activates signalling cascades leading to phosphorylation-dependent desensitization of MLCK.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tara Billman for assistance with maintaining the mice and genotyping. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL26043. This work was also supported by the Moss Heart Fund and the Fouad A. and Val Imm Bashour Distinguished Chair in Physiology (J.T.S.).

Glossary

- α,β-meATP

α,β-methyleneATP

- CaM

calmodulin

- CPI-17

PKC-potentiated protein phosphatase 1 inhibitor protein of 17 kDa

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- EFS

electric field stimulation

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- MLCP

myosin light chain phosphatase

- MYPT1

myosin phosphatase targeting subunit-1

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKD

protein kinase D

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- RLC

myosin regulatory light chain

- UBSM

urinary bladder smooth muscle

Author contributions

K.E.K. and J.T.S. conceived the experimental approach; M.-H.T. and K.E.K. designed the experiments; M.-H.T. performed the experiments; M.-H.T., J.T.S. and K.E.K. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Abrams P, Andersson KE, Buccafusco JJ, Chapple C, de Groat WC, Fryer AD, Kay G, Laties A, Nathanson NM, Pasricha PJ, Wein AJ. Muscarinic receptors: their distribution and function in body systems, and the implications for treating overactive bladder. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:565–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aita Y, Kurebayashi N, Hirose S, Maturana AD. Protein kinase D regulates the human cardiac L-type voltage-gated calcium channel through serine 1884. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3903–3906. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson KE, Arner A. Urinary bladder contraction and relaxation: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:935–986. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brading AF, Mostwin JL. Electrical and mechanical responses of guinea-pig bladder muscle to nerve stimulation. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;98:1083–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brading AF, Williams JH. Contractile responses of smooth muscle strips from rat and guinea-pig urinary bladder to transmural stimulation: effects of atropine and alpha,beta-methylene ATP. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;99:493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield MP, Birdsall NJ. International Union of Pharmacology. XVII. Classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:279–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn JC, Michnoff CH, Hsu LC, Slaughter CA, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Sites phosphorylated in myosin light chain in contracting smooth muscle. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:19166–19173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding HL, Ryder JW, Stull JT, Kamm KE. Signaling processes for initiating smooth muscle contraction upon neural stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15541–15548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900888200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlu-Kandilci NT, Brading AF. Involvement of Rho kinase and protein kinase C in carbachol-induced calcium sensitization in β-escin skinned rat and guinea-pig bladders. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:376–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder CC. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: signal transduction through multiple effectors. FASEB J. 1995;9:619–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleichman M, Schneider T, Fetscher C, Michel MC. Signal transduction underlying carbachol-induced contraction of rat urinary bladder. II. Protein kinases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:54–58. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.058255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei E, Hofmann F, Wegener JW. Phospholipase C mediated Ca2+ signals in murine urinary bladder smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;610:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry CH, Meng E, Young JS. The physiological function of lower urinary tract smooth muscle. Auton Neurosci. 2010;154:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Rubin CS. Protein kinase D: coupling extracellular stimuli to the regulation of cell physiology. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:785–796. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geguchadze R, Zhi G, Lau KS, Isotani E, Persechini A, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Quantitative measurements of Ca2+/calmodulin binding and activation of myosin light chain kinase in cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;557:121–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01456-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Brading AF, Suzuki H. Correlation between spontaneous electrical, calcium and mechanical activity in detrusor smooth muscle of the guinea-pig bladder. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:183–193. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Bramich NJ, Hirst GD. Mechanisms of excitatory neuromuscular transmission in the guinea-pig urinary bladder. J Physiol. 2000;524:565–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He WQ, Peng YJ, Zhang WC, Lv N, Tang J, Chen C, Zhang CH, Gao S, Chen HQ, Zhi G, Feil R, Kamm KE, Stull JT, Gao X, Zhu MS. Myosin light chain kinase is central to smooth muscle contraction and required for gastrointestinal motility in mice. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:610–620. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He WQ, Qiao YN, Zhang CH, Peng YJ, Chen C, Wang P, Gao YQ, Chen X, Tao T, Su XH, Li CJ, Kamm KE, Stull JT, Zhu MS. Role of myosin light chain kinase in regulation of basal blood pressure and maintenance of salt-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H584–H591. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01212.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde SS, Choppin A, Bonhaus D, Briaud S, Loeb M, Moy TM, Loury D, Eglen RM. Functional role of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in the urinary bladder of rats in vitro and in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1409–1418. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Elementary purinergic Ca2+ transients evoked by nerve stimulation in rat urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2005;564:201–212. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner TJ, Werner ME, Nausch B, Vial C, Evans RJ, Nelson MT. Nerve-evoked purinergic signalling suppresses action potentials, Ca2+ flashes and contractility evoked by muscarinic receptor activation in mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2009;587:5275–5288. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horman S, Morel N, Vertommen D, Hussain N, Neumann D, Beauloye C, El Najjar N, Forcet C, Viollet B, Walsh MP, Hue L, Rider MH. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates and desensitizes smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18505–18512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A, Menice CB, Laporte R, Morgan KG. Mechanisms of smooth muscle contraction. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:967–1003. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huster M, Frei E, Hofmann F, Wegener JW. A complex of CaV1.2/PKC is involved in muscarinic signalling in smooth muscle. FASEB J. 2010;24:2651–2659. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-149856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isotani E, Zhi G, Lau KS, Huang J, Mizuno Y, Persechini A, Geguchadze R, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Real-time evaluation of myosin light chain kinase activation in smooth muscle tissues from a transgenic calmodulin-biosensor mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6279–6284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308742101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam Y, Exton JH. Role of phospholipase D in the activation of protein kinase D by lysophosphatidic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm KE, Stull JT. The function of myosin and myosin light chain kinase phosphorylation in smooth muscle. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1985;25:593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.25.040185.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm KE, Stull JT. Dedicated myosin light chain kinases with diverse cellular functions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4527–4530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishii K, Hisayama T, Takayanagi I. Comparison of contractile mechanisms by carbachol and ATP in detrusor strips of rabbit urinary bladder. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1992;58:219–229. doi: 10.1254/jjp.58.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T, Eto M, Woodsome TP, Khalequzzaman M. Phosphorylation of the myosin phosphatase targeting subunit and CPI-17 during Ca2+ sensitization in rabbit smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2003;546:879–889. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C, Vainorius E, Wier WG. Purinergic and adrenergic Ca2+ transients during neurogenic contractions of rat mesenteric small arteries. J Physiol. 2003;549:801–808. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui M, Motomura D, Karasawa H, Fujikawa T, Jiang J, Komiya Y, Takahashi S, Taketo MM. Multiple functional defects in peripheral autonomic organs in mice lacking muscarinic acetylcholine receptor gene for the M3 subtype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9579–9584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SA, Rozengurt E, Cantrell D. Characterization of serine 916 as an in vivo autophosphorylation site for protein kinase D/protein kinase Cμ. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26543–26549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin J, Evans BA, Csikasz RI, Bengtsson T, Summers RJ, Hutchinson DS. The M3-muscarinic acetylcholine receptor stimulates glucose uptake in L6 skeletal muscle cells by a CaMKK-AMPK-dependent mechanism. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1104–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Isotani E, Huang J, Ding H, Stull JT, Kamm KE. Myosin light chain kinase activation and calcium sensitization in smooth muscle in vivo. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C358–C364. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.90645.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nausch B, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT. Nerve-released acetylcholine contracts urinary bladder smooth muscle by inducing action potentials independently of IP3-mediated calcium release. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R878–R888. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00180.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M, Stull JT, Kamm KE, Mumby MC. Site-specific dephosphorylation of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase by protein phosphatases 1 and 2A. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11915–11920. doi: 10.1021/bi00162a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poley RN, Dosier CR, Speich JE, Miner AS, Ratz PH. Stimulated calcium entry and constitutive RhoA kinase activity cause stretch-induced detrusor contraction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;599:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puetz S, Lubomirov LT, Pfitzer G. Regulation of smooth muscle contraction by small GTPases. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:342–356. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00023.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokolya A, Singer HA. Inhibition of CaM kinase II activation and force maintenance by KN-93 in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C537–C545. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumenapp U, Asmus M, Schablowski H, Woznicki M, Han L, Jakobs KH, Fahimi-Vahid M, Michalek C, Wieland T, Schmidt M. The M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor expressed in HEK-293 cells signals to phospholipase D via G12 but not Gq-type G proteins: regulators of G proteins as tools to dissect pertussis toxin-resistant G proteins in receptor-effector coupling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2474–2479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Fetscher C, Krege S, Michel MC. Signal transduction underlying carbachol-induced contraction of human urinary bladder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004a;309:1148–1153. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.063735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Hein P, Michel MC. Signal transduction underlying carbachol-induced contraction of rat urinary bladder. I. Phospholipases and Ca2+ sources. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004b;308:47–53. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.058248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1325–1358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streets AJ, Needham AJ, Gill SK, Ong AC. Protein kinase D-mediated phosphorylation of polycystin-2 (TRPP2) is essential for its effects on cell growth and calcium channel activity. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3853–3865. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull JT, Hsu LC, Tansey MG, Kamm KE. Myosin light chain kinase phosphorylation in tracheal smooth muscle. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16683–16690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull JT, Krueger JK, Kamm KE, Gao ZH, Padre R. Myosin light chain kinase. In: Bárány M, editor. Biochemistry of Smooth Muscle. New York: Academic; 1996. pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Stull JT, Tansey MG, Tang DC, Word RA, Kamm KE. Phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase: a cellular mechanism for Ca2+ desensitization. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;127–128:229–237. doi: 10.1007/BF01076774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R, Nishimura J, Hirano K, Seki N, Naito S, Kanaide H. Ca2+ sensitization in contraction of human bladder smooth muscle. J Urol. 2004;172:748–752. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000130419.32165.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang DC, Kubota Y, Kamm KE, Stull JT. GTPγS-induced phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase in smooth muscle. FEBS Lett. 1993;331:272–275. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80351-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tansey MG, Word RA, Hidaka H, Singer HA, Schworer CM, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase by the multifunctional calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12511–12516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira CE, Jin L, Priviero FB, Ying Z, Webb RC. Comparative pharmacological analysis of Rho-kinase inhibitors and identification of molecular components of Ca2+ sensitization in the rat lower urinary tract. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vial C, Evans RJ. P2X receptor expression in mouse urinary bladder and the requirement of P2X1 receptors for functional P2X receptor responses in the mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:1489–1495. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QJ. PKD at the crossroads of DAG and PKC signalling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Kendig DM, Smolock EM, Moreland RS. Carbachol-induced rabbit bladder smooth muscle contraction: roles of protein kinase C and Rho kinase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F1534–F1542. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00095.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener JW, Schulla V, Lee TS, Koller A, Feil S, Feil R, Kleppisch T, Klugbauer N, Moosmang S, Welling A, Hofmann F. An essential role of Cav1.2 L-type calcium channel for urinary bladder function. FASEB J. 2004;18:1159–1161. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1516fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner ME, Knorn AM, Meredith AL, Aldrich RW, Nelson MT. Frequency encoding of cholinergic- and purinergic-mediated signalling to mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle: modulation by BK channels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R616–R624. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00036.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest M, Hiller N, Braeter M, Hakenberg OW, Wirth MP, Ravens U. Contribution of Ca2+ influx to carbachol-induced detrusor contraction is different in human urinary bladder compared to pig and mouse. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;565:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JS, Meng E, Cunnane TC, Brain KL. Spontaneous purinergic neurotransmission in the mouse urinary bladder. J Physiol. 2008;586:5743–5755. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.162040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zderic SA, Sillen U, Liu GH, Snyder MC, 3rd, Duckett JW, Gong C, Levin RM. Developmental aspects of excitation contraction coupling of rabbit bladder smooth muscle. J Urol. 1994;152:679–681. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WC, Peng YJ, Zhang GS, He WQ, Qiao YN, Dong YY, Gao YQ, Chen C, Zhang CH, Li W, Shen HH, Ning W, Kamm KE, Stull JT, Gao X, Zhu MS. Myosin light chain kinase is necessary for tonic airway smooth muscle contraction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5522–5531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.062836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]