Abstract

MDMX is an important regulator of p53 during embryonic development and malignant transformation. Previous studies showed that casein kinase 1α (CK1α) stably associates with MDMX, stimulates MDMX-p53 binding, and cooperates with MDMX to inactivate p53. However, the mechanism by which CK1α stimulates MDMX-p53 interaction remains unknown. Here, we present evidence that p53 binding by the MDMX N-terminal domain is inhibited by the central acidic region through an intramolecular interaction that competes for the p53 binding pocket. CK1α binding to the MDMX central domain and phosphorylation of S289 disrupts the intramolecular interaction, allowing the N terminus to bind p53 with increased affinity. After DNA damage, the MDMX-CK1α complex is disrupted by Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of MDMX at S367, leading to reduced MDMX-p53 binding. Therefore, CK1α is an important functional partner of MDMX. DNA damage activates p53 in part by disrupting CK1α-MDMX interaction and reducing MDMX-p53 binding affinity.

INTRODUCTION

The p53 tumor suppressor can be activated by numerous cellular and environmental signals and induces the expression of genes that regulate metabolism, cell growth, division, and apoptosis (49). MDM2 and MDMX are key regulatory proteins that control p53 level and transcriptional activity. Recent studies suggested that the MDM2/MDMX module is largely responsible for enabling p53 to be highly responsive to stress, thus maintaining genomic stability and enhancing cellular and organismal robustness. The importance of p53 in maintaining normal homeostasis is underscored by the frequent p53 mutation or MDM2/MDMX dysregulation in human cancer.

MDM2 and MDMX are homologs that bind to p53 with high affinity (31). Genetic analyses showed that both MDM2 and MDMX are essential for controlling p53 activity during embryogenesis (17, 35, 38). The role of MDMX appears to be less critical than that of MDM2 in adult tissues, as shown by somatic knockout experiments (13, 30, 55). MDM2 is a classic p53 transcriptional target, forming a negative feedback loop (54). Bona fide p53 binding sites are also found in intron 1 of the human MDMX gene, and p53 activation leads to moderate induction of MDMX transcription (23, 42). Induction of MDMX by p53 was also observed in a mouse model after somatic deletion of casein kinase 1α (CK1α), which triggers oncogenic stress and p53 activation (9). The magnitude of MDMX mRNA induction after p53 activation (1.5 to 3-fold) is moderate compared to that of MDM2 (>10-fold) and displays cell type specificity. Therefore, MDMX is a p53 target gene that may also provide a negative feedback response to p53 activation.

Investigations of p53 activation by DNA damage suggest that phosphorylation of p53, MDM2, and MDMX cooperate to achieve rapid and robust responses. MDM2-p53 binding is essential for degradation of p53 and has been extensively studied. DNA double-strand breaks induce phosphorylation of p53 S15 by DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) and ATM (1, 33, 45). ATM also activates Chk2, which in turn phosphorylates p53 on S20 that is part of the MDM2 binding site (1, 3, 44, 45). These findings suggest that p53 phosphorylation on the N terminus inhibits MDM2 binding. Phosphorylation of MDM2 is also a key step in p53 stabilization by DNA damage. MDM2 is phosphorylated by ATM, ATR, and C-Abl near the C terminus (32, 46, 47). MDM2 phosphorylation after DNA damage correlates with reduced dimerization and oligomerization of the RING domain, suggesting that higher-order complex formation is needed for efficient polyubiquitination of p53 (7, 8). ATM phosphorylation of MDM2 at S395 also stimulates RNA binding by the RING domain, which has been shown to inhibit E3 ligase activity (11, 28). Furthermore, MDM2 phosphorylation by ATM regulates the interaction between the MDM2 acidic domain and p53 DNA binding domain (8). This interaction is important for inducing p53 misfolding and promoting p53 ubiquitination. Therefore, phosphorylation sites near the MDM2 C terminus affect the structure and function of multiple domains, suggesting that these domains are allosterically linked to the phosphorylation sites.

MDMX lacks robust E3 ligase activity, but it plays an important role in regulating p53 transcriptional function. MDMX expression and phosphorylation by the ATM/Chk2 pathway have significant roles in p53 DNA damage response in adult mice (48, 52). The MDMX level is controlled by MDM2-mediated ubiquitination in a stress-dependent fashion (19, 37). Significant degradation of MDMX occurs after DNA damage through phosphorylation on several C-terminal sites (S342 and S367 by Chk2 and S403 by ATM), with S367 phosphorylation being the most critical (5, 40). Furthermore, ribosomal stress promotes MDMX degradation through L11-MDM2 interaction (12), and oncogenic stress promotes MDMX degradation through ARF expression (26). Therefore, key signaling mechanisms that block p53 degradation also simultaneously enhance MDMX degradation by MDM2. These observations underscore the coordinated control of MDM2 and MDMX, which is critical for proper p53 response.

Although biochemical studies in culture and cell-free assays suggest that MDMX regulates p53 degradation through heterodimerization with MDM2 (27, 51), MDMX knockout in mice leads to p53 activation without significant stabilization (10). Therefore, the mechanism of p53 inhibition by MDMX remains poorly characterized. Affinity purification of MDMX has identified CK1α and 14-3-3 as two major binding proteins (6). MDMX–14-3-3 interaction is stimulated by Chk2 phosphorylation of S367 and regulates MDMX nuclear import and ubiquitination (22). The MDMX RING domain also interacts specifically with 5S rRNA (25). Interaction with 5S rRNA leads to stabilization of MDMX, which may inhibit p53 function during growth responses. CK1α interacts with the central region of MDMX, including the acidic domain and zinc finger, promotes phosphorylation of S289, and stimulates MDMX-p53 binding through an unknown mechanism (6). CK1α is an abundant serine/threonine kinase that regulates multiple cellular pathways, such as Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and circadian rhythm (20). Recent studies also suggest that CK1α promotes the phosphorylation of the MDM2 acidic domain and regulates p53 stability (15). Whether MDMX-CK1α interaction is regulated during the stress response remains unknown.

In this report, we show that CK1α enhances MDMX affinity for p53 by disrupting an intramolecular interaction in MDMX. Furthermore, DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of MDMX at S367 inhibits CK1α binding, which leads to inhibition of MDMX-p53 interaction. These results provide new insight on the mechanism of p53 regulation by MDMX and implicate MDMX-CK1α complex as a key target of DNA damage signaling that leads to p53 activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and cell lines.

MDMX, MDM2, p53, and CK1α constructs used in this study are of human origin. MDMX deletion mutants were generated by PCR amplification and subcloning, and MDMX point mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene). MDM2-MDMX hybrid constructs were provided by Zhimin Yuan. MDMX/p53 double-null murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) (41.4 cells, provided by Guillermina Loano), H1299 (non-small cell lung carcinoma, p53-null), U2OS (osteosarcoma, wild-type p53), HCT116 (colon carcinoma, wild-type p53), and HCT116-Chk2−/− (provided by Bert Vogelstein) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transfection of H1299 cells was performed using a standard calcium phosphate precipitation protocol. U2OS cells with stable expression of MDMX mutants were generated by infection with pLenti-MDMX virus followed by zeocin selection (ViraPower T-REX lentiviral expression system; Invitrogen). To knock down CK1α, cells were transfected for 48 h with 200 nM control short interfering RNA (siRNA) (AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT) or CK1α siRNAs (1, AAGCAAGCUCUAUAAGAUUCU; 2, AAACGGUGGUAUGGUCAGGAA; 3, AACAAGGCAACACAUACCAUA) using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to instructions from the supplier.

Western blotting.

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g, and the insoluble debris was discarded. Cell lysate (10 to 50 μg of protein) was fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon P filters (Millipore). The filter was blocked for 1 h with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% Tween 20. The following antibodies were used: DO-1 (Pharmingen) for p53, 3G9 for MDM2 (4), and 10G11 or 8C6 for MDMX (24). CK1α antibody and anti-p21WAF antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Myc epitope tag antibody was from Cell Signaling. The filter was developed using the Supersignal reagent (Thermo Scientific). PS367 phosphorylation-specific antibody was generated previously (5). PS289 phosphorylation-specific rabbit antibody was raised against phosphorylated MDMX peptide DSK(pS)LSDDT (GenScript) and affinity purified. MDMX phosphorylation analysis was carried out by immunoprecipitation (IP) using 8C6 antibody from 0.5 to 2 mg cell extract followed by Western blotting using the phosphorylation-specific antibody.

Immunoprecipitation.

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g, and the insoluble debris was discarded. Cell lysate (200 to 1000 μg of protein) was immunoprecipitated with 8C6 against MDMX and protein A-agarose beads (Sigma) for 18 h at 4°C.

GST pulldown assay.

Bacterial lysate expressing glutathione S-transferase (GST), GST–MDMX-1-120, and GST–MDM2-1-150 were applied to glutathione-agarose beads according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce). The beads loaded with GST fusion proteins were incubated with H1299 lysate transiently transfected with Myc–MDMX-100-361 with or without CK1α at 4°C for 2 h. Different concentrations of pDI (LTFEHYWAQLTS) or pDI-3A (LTAEHYAAQATS; residues different from pDI are underlined) were added and preincubated for 10 min before coincubation with Myc–MDMX-100-361 lysate for 1 h at 4°C in inhibition experiments. The beads were washed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholate), boiled in Laemmli sample buffer, and detected by Western blotting.

ELISA.

His6-tagged human p53 was expressed in Escherichia coli and affinity purified by binding to Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) beads under nondenaturing conditions. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were incubated with 2.5 μg/ml His6-p53 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 16 h. After being washed with PBS plus 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), the plates were blocked with PBS plus 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20 (PBSMT) for 0.5 h. H1299 cells were transfected with MDMX and CK1α. The levels of MDMX or mutant expression were normalized by dilution with nontransfected H1299 lysate. H1299 lysate expressing MDMX (0 to 160 μg protein) was mixed with 0 to 160 μg nontransfected H1299 lysate to obtain identical final protein concentrations and volumes. The mixtures were added to the p53-coated wells and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were washed with PBST and incubated with MDMX antibody 8C6 in PBSMT for 1 h, followed by washing and incubation with horseradish peroxidase–rabbit-anti-mouse Ig antibody for 1 h. The plates were developed by incubation with TMB peroxidase substrate (KPL) and measured by absorbance at 450 nm.

ITC.

MDMX-1-120 and MDMX-1-361 were cloned into pGEX-6P1, expressed as GST fusion proteins, and purified from E. coli. The GST moiety was removed after cleavage with PreScission protease. The binding of biotin-p53 peptide to the protein constructs was analyzed with a MicroCal iTC200 titration calorimeter (GE Healthcare). The protein was exchanged into binding buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT). For the titration of the protein constructs, 17 (for MDMX-1-120) and 19 (for MDMX-1-361) aliquots (2.01 μl each) of the peptide (600 μM) were injected into 200 μl of the protein solutions of MDMX-1-120 (69 μM) and MDMX-1-361 (50 μM) at 15°C. The isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) cell mixture was constantly stirred at 1,000 rpm and recorded for 300 s between injections at low feedback. The corrected heat values were fitted using a nonlinear least-square curve-fitting algorithm (Microcal Origin 7.0) to obtain the stoichiometry (N), dissociation constant (Kd), and change in enthalpy of the enzyme-ligand interaction (ΔH). Biotin-p53 peptide (Bio-Acp-LSQETFSDLWKLLPE) was synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ).

Luciferase reporter assay.

Cells (50,000/well) were plated in 24-well plates and transfected with a mixture containing 10 ng p53-responsive BP100-luciferase reporter plasmid (15), 5 ng CMV-lacZ plasmid, 0.1 ng p53 expression plasmid, 20 ng MDMX plasmid, and 20 ng CK1α plasmid. Transfection was achieved using Lipofectamine Plus reagents (Invitrogen), and cells were analyzed for luciferase and beta-galactosidase expression after 24 h. The luciferase/beta-galactosidase activity ratios were used as indicators of p53 transcription activity.

RESULTS

CK1α promotes MDMX-p53 binding.

A previous study showed that MDMX copurified with nearly stoichiometric amounts of CK1α, which stimulates MDMX-p53 binding in transfected cells (6). MDMX-CK1α copurification was also independently observed in a recent report (25). To further investigate the mechanism by which CK1α regulates MDMX, we performed experiments to confirm the effect of CK1α on MDMX-p53 binding. As reported previously, CK1α expression promoted MDMX-p53 binding in co-IP assays of transfected H1299 cells (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, we found that alanine substitution of the CK1α phosphorylation site on MDMX (S289A) reduced the regulation by CK1α. This suggests that CK1α phosphorylation of S289 is necessary for stimulating p53 binding. Mutation of an MDMX zinc finger cysteine (C306S) abrogated CK1α binding and prevented stimulation by CK1α. Interestingly, MDMX-C306S showed moderately but reproducibly increased binding to p53 in the absence of CK1α, suggesting that the mutation causes a conformational change that mimics the effect of CK1α binding (Fig. 1a). Mutation of the Chk2 phosphorylation site (S367A) increased binding to CK1α and p53, suggesting that S367 phosphorylation regulates MDMX-CK1α interaction. We also tested CK1ε and CK1δ isoforms and found that they had no effect on MDMX-p53 binding (Fig. 1e). This is consistent with previous affinity purifications showing that only CK1α was copurified as a stable partner of MDMX (6).

Fig 1.

CK1α promotes MDMX-p53 binding in vivo. (a) H1299 cells transfected as indicated were immunoprecipitated with MDMX antibody, and coprecipitated p53 and CK1α were detected by Western blotting (WB). (b) H1299 cells were transfected with MDMX and CK1α. MDMX was immunoprecipitated and probed with anti-phospho-S289 antibody. Phosphatase (CIP) treatment was performed on immunoprecipitated MDMX prior to pS289 Western blotting. (c) H1299 cells were transfected as indicated, and p21 expression was detected by Western blotting. (d) CK1α was knocked down by siRNAs in HCT116 cells, and p53-MDMX binding was determined by p53 IP and Western blotting for MDMX. (e) The ability of different CK1 isoforms to regulate MDMX-p53 binding was compared using the assay described for panel a. WCE, whole-cell extract.

To determine whether MDMX is phosphorylated by CK1α in vivo, phosphorylation-specific antibody was generated against S289. The pS289 antibody detected significant basal-level phosphorylation of MDMX in transfection assays, consistent with MDMX interaction with endogenous CK1α. Cotransfection of ectopic CK1α further increased MDMX S289 phosphorylation (Fig. 1b). The specificity of the pS289 antibody was confirmed by loss of reactivity to phosphatase-treated MDMX and complete lack of reactivity to the S289A mutant (Fig. 1b).

The expression of CK1α also cooperated with MDMX to inhibit p53. The transient transfection of p53 into H1299 cells induced expression of p21. In this assay, MDMX alone was inefficient in suppressing p53 function, whereas MDMX-CK1α coexpression inhibited p21 expression. Furthermore, S367A-CK1α showed more efficient inhibition of p53 (Fig. 1c), suggesting that S367 phosphorylation regulates MDMX-CK1α interaction (further addressed below). To test whether endogenous CK1α regulates MDMX-p53 binding, CK1α was knocked down using siRNA in HCT116 cells. Depletion of CK1α reduced endogenous MDMX-p53 binding (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that CK1α binding and phosphorylation of MDMX are necessary for efficient MDMX-p53 interaction in vivo.

CK1α increases MDMX-p53 binding affinity in vitro.

CK1α interacts with the MDMX central region (residues 150 to 350), which is separate from the N-terminal p53 binding domain (residues 1 to 120). It is unclear how this interaction stimulates MDMX-p53 binding in vivo. To test whether CK1α increases MDMX binding affinity for p53 in vitro, we performed ELISA using p53 immobilized on plates to capture MDMX from transfected H1299 extract. The results showed that MDMX coexpressed with CK1α was captured by p53 more efficiently than MDMX expression alone (Fig. 2a). MDMX-C306S showed enhanced p53 binding in vitro without CK1α and was not further stimulated by CK1α. Furthermore, MDMX-S289A showed weak p53 binding that was not stimulated by CK1α, suggesting that phosphorylation of S289 by CK1α was important for stimulating p53 binding. These results showed that CK1α binds to MDMX and phosphorylates S289 to stimulate p53 binding affinity.

Fig 2.

CK1α promotes MDMX-p53 binding in vitro. (a) ELISA plates coated with His6-p53 were incubated with H1299 lysate expressing the MDMX wild type and C306S and S289A mutants in the presence or absence of CK1α. The amount of captured MDMX was detected using MDMX antibody. (b) Western blot confirmation of equalized MDMX levels in lysate used for ELISA. (c) Gal4–p53-1-82 was cotransfected with MDMX and CK1α into H1299, and the binding between MDMX and Gal4–p53-1-82 was detected by MDMX IP and p53 Western blotting. Control IP contained MDMX antibody but no cell extract. The antibody background band is marked by an asterisk.

The MDM2 acidic domain interacts weakly with the p53 core domain (56). A similar second-site interaction between the MDMX acidic domain and p53 core in the presence of CK1α could explain the enhanced p53 binding. However, we failed to detect coprecipitation between MDMX-100-361 (central domain) and p53 (data not shown). To test whether CK1α-stimulated MDMX-p53 binding can occur in the absence of the p53 core domain, a Gal4–p53-1-82 fusion was cotransfected with MDMX and CK1α. The results showed that p53-1-82 binding to MDMX was also stimulated by CK1α (Fig. 2c) independent of the p53 core domain. These results suggest that CK1α regulates the affinity of the MDMX N-terminal p53 binding domain.

CK1α stimulates p53 binding by an MDM2-MDMX chimeric molecule.

If the MDMX N-terminal p53 binding domain is structurally coupled to the central domain, CK1α binding to the central domain may allosterically affect p53 binding by the N terminus. If this is the case, replacing the MDMX N terminus with the MDM2 N-terminal domain should destroy such coupling and abrogate the response to CK1α due to sequence and structural incompatibility. However, we found that when residues 1 to 108 of MDMX were replaced by the corresponding MDM2 sequence, p53 binding by the chimeric construct was still stimulated by CK1α similarly to wild-type MDMX (Fig. 3a). Replacement of a larger MDMX segment (residues 1 to 222) with MDM2 sequence destroyed CK1α interaction and response, because the fusion altered the critical region (residues 150 to 350) required for CK1α binding (Fig. 3a). This result showed that CK1α can regulate p53 binding affinity of a heterologous domain attached to the MDMX central region.

Fig 3.

CK1α stimulates p53 binding by MDM2-MDMX chimera. (a) H1299 cells transfected with p53, FLAG-tagged MDM2-MDMX hybrid constructs, and CK1α were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads followed by Western blotting for coprecipitated p53 and CK1α. (b) Diagram of MDM2-MDMX chimeric constructs.

CK1α disrupts an intramolecular interaction in MDMX.

A significant region (residues 120 to 185) between the p53 binding domain and central domain of MDMX is predicted to be unstructured (Fig. 4a), suggesting that it functions as a flexible linker. We found that GST–MDMX-1-120 can specifically capture the MDMX-100-361 central fragment from transfected H1299 lysate. GST–MDMX-1-30 (or GST–MDMX-1-50) without a functional p53 binding domain did not interact with MDMX-100-361. Importantly, coexpression of CK1α with MDMX-100-361 strongly inhibited the binding (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that CK1α binding disrupts an intramolecular interaction between the N-terminal p53 binding domain and the central domain. Interestingly, the N terminus of MDM2 can also bind to the MDMX-100-361 fragment in a CK1α-sensitive fashion (Fig. 4c), suggesting that the p53 binding pocket is involved in the interaction. Using similar baits, we failed to detect binding with the MDM2-100-361 fragment (data not shown), suggesting that such intramolecular interaction does not occur in MDM2. Regulation of the interaction by CK1α requires kinase activity, since the kinase-deficient CK1α-K46D mutant failed to inhibit the binding (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, mutating the CK1α phosphorylation site in the central fragment (MDMX-100-361-S289A) abrogated the regulation by CK1α (Fig. 4e), suggesting that CK1α inhibits the internal binding by phosphorylating S289.

Fig 4.

CK1α disrupts MDMX N-terminal-central domain interaction. (a) PONDR analysis of MDMX amino acid sequence. Segments with low PONDR scores (below 0.5) are predicted to be stably folded, and high scores (near 1) indicate disorder. (b) For the top panel, glutathione-agarose beads loaded with the indicated GST-MDMX fusion proteins were incubated with Myc-tagged MDMX-100-361 expressed in H1299. The captured MDMX-100-361 was detected by Myc Western blotting. The lower panel shows verification of purified GST fusion proteins by Coomassie blue staining. (c) Glutathione beads loaded with GST-MDMX or GST-MDM2 N terminus were incubated with H1299 lysate transfected with Myc–MDMX-100-361 and CK1α. The captured MDMX-100-361 was detected by Myc Western blotting. (d) GST–MDMX-1-120 pulldown of MDMX-100-361 was inhibited by wild-type CK1α but not kinase-deficient CK1α-K46D mutant. (e) Introduction of S289A mutation into MDMX-100-361 abrogates the response to CK1α in the GST–MDMX-1-120 pulldown assay.

The central region of MDMX inhibits p53 binding.

To test whether the central region of MDMX suppresses p53 binding by the N-terminal domain, GST–p53-1-82 was used to capture different MDMX fragments from transfected H1299 lysate. The p53 binding efficiency of MDMX-1-200 was significantly higher than that of MDMX-1-300 or MDMX-1-490 (Fig. 5a), suggesting that the presence of the central region (residues 200 to 300) reduces the p53 binding affinity of the N-terminal domain. Further analysis using MDMX acidic domain internal deletion mutants also showed increased binding to GST-p53 in vitro (Fig. 5b and c), which correlates with more potent inhibition of p53 transcriptional activity in reporter gene assays using p53/MDMX-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Fig. 5d). These results suggest that residues 200 to 305 of the MDMX acidic region are important for inhibiting p53 binding by the N-terminal domain.

Fig 5.

MDMX central domain inhibits interaction with p53. (a and b) Glutathione-agarose beads loaded with GST–p53-1-82 were incubated with similar amounts of MDMX truncation mutants (a) and internal deletion mutants (b) expressed in H1299, and the captured MDMX was detected by Western blotting. The position of each mutant MDMX protein of interest is marked by an arrow head. (c) Diagram of MDMX mutants and summary of p53 binding activity. (d) The ability of MDMX internal deletion mutants to inhibit p53 transactivation function was analyzed by a reporter assay after cotransfection with p53 and p53-responsive luciferase reporter BP100-luc into p53/MDMX double null mouse embryo fibroblasts (41.4 cells).

To quantitatively measure the effect of the MDMX central region on p53 binding, MDMX-1-120 and MDMX-1-361 fragments were expressed in E. coli. The purified MDM2 proteins were analyzed for p53 peptide (14-LSQETFSDLWKLLPE-28) binding by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). The p53 peptide displayed high binding affinity to the MDMX-1-120 fragment (Kd = 0.51 μM), whereas binding to MDMX-1-361 was weak (Kd = ∼17 μM) (Fig. 6a). Combined, these results demonstrate that the MDMX central region significantly reduces the binding affinity of the N-terminal domain for p53.

Fig 6.

MDMX central domain inhibits N-terminal interaction with p53. (a) MDMX-1-120 and MDMX-1-361 fragments were analyzed for binding to p53 peptide using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Dissociation constants (Kd), stoichiometry (N), and changes in enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) for peptide binding are summarized in the table. The asterisk indicates that due to the weak binding of MDMX-1-361, the best fit for Kd determination was achieved by fixing the N value to 1.0. (b) Glutathione beads loaded with GST–MDMX-1-120 were incubated with H1299 lysate expressing Myc-tagged MDMX-100-361 in the presence of pDI or pDI-3A peptides. The captured MDMX-100-361 protein was detected by Western blotting. (c) MDMX and Myc-CK1α were transfected separately into H1299 cells. MDMX lysate was preincubated with 5 μM pDI and pDI-3A peptides, followed by coincubation with Myc-CK1α lysate. In vitro MDMX-CK1α complex formation was analyzed by MDMX IP-Myc Western blotting.

MDMX N-terminal and central domains interact through p53 mimicry.

The results described above suggest that the p53 binding pocket in the N-terminal domain of MDMX also interacts weakly with the central acidic region through p53 mimicry. We previously identified an optimized peptide (pDI; LTFEHYWAQLTS) that mimics the p53 N-terminal sequence (17-ETFSDLWKLLPE-28) and binds to the MDMX hydrophobic pocket with significantly higher affinity than that of the p53 peptide (14, 41). Here, we found that the pDI peptide inhibited the binding between GST–MDMX-1-120 and MDMX-100-361 (Fig. 6b), whereas a mutant peptide with 3 alanine substitutions on key hydrophobic residues (pDI-3A; LTAEHYAAQATS) had no effect. This result suggests that the N-terminal p53 binding pocket interacts with a sequence or structure in the central region that mimics p53, resulting in autoinhibition. CK1α may eliminate this autoinhibitory effect and increase the availability of the N-terminal pocket for p53 binding. This model is consistent with the CK1α responsiveness of the MDM2-MDMX hybrid construct pzy3 (Fig. 3) and the ability of the MDM2 N-terminal domain to bind the MDMX central fragment (Fig. 4c).

The mechanism proposed above suggests that filling the p53 binding pocket with pDI peptide releases the central domain and increases MDMX-CK1α binding. To test this prediction, MDMX-CK1α binding in vitro was determined by IP-Western blotting after coincubation of H1299 extract expressing MDMX and Myc-tagged CK1α. Preincubation of MDMX with pDI peptide stimulated MDMX-CK1α coprecipitation as expected, whereas pDI-3A peptide had no effect (Fig. 6c). These results suggest that the central region of MDMX interacts with the N-terminal pocket through p53 mimicry, which is abrogated by CK1α binding and phosphorylation of S289. The central region of MDMX has no sequence homology to the p53 N terminus. The acidic domain internal deletion mutants showed that nonoverlapping deletions increased p53 binding affinity (Fig. 5c). This suggests that the interaction with the N-terminal pocket is mediated by multiple weak binding sites or by a 3-dimensional structure formed by the MDMX central region.

DNA damage inhibits MDMX-CK1α binding through phosphorylation of S367.

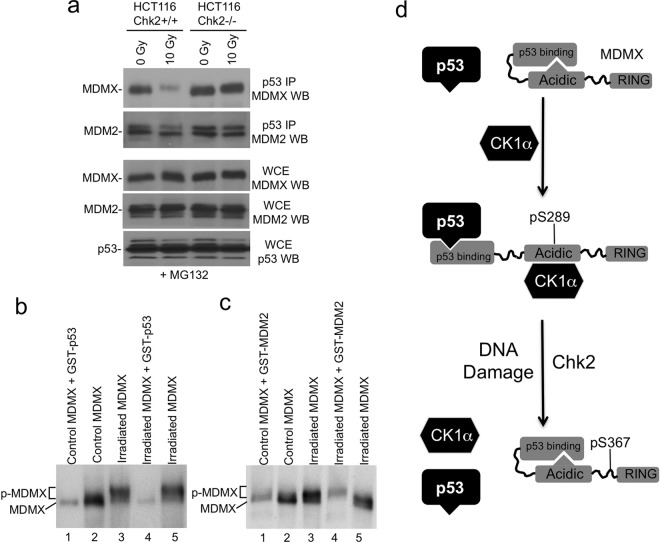

Previous affinity purification experiments showed that a significant fraction of MDMX is present in a complex with CK1α (6). We tested whether MDMX-CK1α interaction is regulated by stresses that activate p53. In a co-IP assay, endogenous MDMX-CK1α binding was significantly reduced after gamma irradiation (IR) in wild-type HCT116 cells but not in HCT116-Chk2−/− cells (Fig. 7a). Several DNA damaging agents (camptothecin, etoposide, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil) also inhibited MDMX-CK1α binding in a Chk2-dependent fashion (data not shown), suggesting that MDMX-CK1α interaction is regulated by DNA damage.

Fig 7.

Phosphorylation of S367 by Chk2 regulates MDMX-CK1α interaction. (a) Wild-type and Chk2-null HCT116 cells were treated with 10 Gy IR in the presence of MG132 (to normalize protein levels). MDMX-CK1α interaction was determined by MDMX IP followed by Western blotting for CK1α. The input showed equal expression levels of each protein. con, control. (b) HCT116 cells were treated with 10 Gy IR in the presence of MG132, and MDMX immunoprecipitated by MDMX antibody or CK1α antibody (loading was adjusted to obtain similar levels of total MDMX) was probed using S367 phosphorylation-specific antibody (pS367) or MDMX polyclonal antibody. (c) U2OS cells stably expressing MDMX and MDMX-S367A were treated with 10 Gy IR and cell extracts were prepared after 2 h and mixed with H1299 extract expressing Myc-CK1α. De novo formation of MDMX-CK1α complex was detected by MDMX IP and Myc Western blotting.

After DNA damage, Chk2 regulates MDMX degradation mainly by phosphorylating S367. To test whether phosphorylation of MDMX S367 also inhibits CK1α binding, HCT116 cells were treated with IR. CK1α was immunoprecipitated, and the coprecipitated MDMX was probed with S367 phosphorylation-specific antibody. The result showed that although a significant amount of MDMX in the total pool was phosphorylated at S367 after IR, MDMX coprecipitated with CK1α was not phosphorylated at S367 (Fig. 7b), suggesting that MDMX containing phosphorylated S367 does not bind CK1α.

DNA damage promotes MDMX nuclear translocation (22, 24), which may affect the binding to CK1α that is predominantly present in the cytoplasm (data not shown). To test whether MDMX phosphorylation directly regulates binding affinity for CK1α, we performed in vitro binding between MDMX stably expressed in U2OS cells and Myc-CK1α transiently expressed in H1299 cells. The use of Myc-CK1α allowed the detection of de novo MDMX-CK1α binding in vitro by Myc Western blotting without the background from preexisting endogenous CK1α-MDMX complex. The result showed that IR treatment abrogated MDMX-CK1α binding but had little effect on MDMX-S367A binding to CK1α (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, nonirradiated MDMX-S367A showed stronger binding to CK1α than wild-type MDMX, probably because it was resistant to basal phosphorylation. Therefore, phosphorylation of MDMX S367 reduces the binding affinity for CK1α independent of its effect on MDMX nuclear translocation.

S289 mediates the effect of S367 phosphorylation on MDMX-p53 binding.

To further test the role of S367 in regulating MDMX-CK1α binding, we examined the ability of the MDMX-S367A mutant to coprecipitate with CK1α after DNA damage in stably transfected U2OS cells. Under overexpression conditions, the binding between ectopic wild-type MDMX and endogenous CK1α was also reduced by IR treatment, similar to the response of endogenous interaction. MDMX-S367A showed moderately increased binding to CK1α, and the binding was not suppressed by IR (Fig. 8a). Consistent with increased CK1α binding, the level of S289 phosphorylation was also elevated in the MDMX-S367A mutant (Fig. 8a). Corresponding to the increased CK1α binding and S289 phosphorylation, MDMX-S367A was more potent than wild-type MDMX in suppressing p53 induction of p21 after DNA damage (Fig. 8a).

Fig 8.

S289 is required to mediate the effect of S367 phosphorylation. (a) U2OS cells stably expressing wild-type MDMX or the MDMX-S367A mutant were treated with 10 Gy IR and analyzed for MDMX-CK1α coprecipitation and S289 phosphorylation after 4 h. (b) H1299 cells were transiently transfected with MDMX mutants, CK1α, and p53. MDMX-p53 binding was determined by IP-Western blotting. (c) U2OS cells stably expressing wild-type MDMX, the S367A mutant, or the S289A/S367A double mutant were treated with 10 Gy IR and analyzed for p21 induction after 4 h.

To determine whether the gain of function by MDMX-S367A requires phosphorylation of S289, an MDMX-S289A/S367A double mutant was generated. When tested in a p53 binding assay, the strong cooperation between MDMX-S367A and CK1α was abrogated by the S289A mutation (Fig. 8b). When stably expressed in U2OS using lentiviral vector, the strong ability of MDMX-S367A to block p21 induction after IR was also reversed by the S289A mutation (Fig. 8c). These results suggest that the increased potency of the S367A mutant was due to elevated CK1α binding and phosphorylation of S289. Due to limited sensitivity of the pS289 antibody, we were not able to analyze endogenous MDMX phosphorylation on S289 (data not shown). Overall the results suggest that phosphorylation of S367 after DNA damage blocks MDMX-CK1α binding, reduces phosphorylation on S289, and neutralizes the ability of MDMX to inhibit p53.

DNA damage inhibits MDMX-p53 binding.

S367 phosphorylation by Chk2 after DNA damage is important for promoting MDMX degradation by MDM2. The results described above suggest that S367 phosphorylation also regulates MDMX-p53 complex formation through disrupting CK1α binding. When HCT116 cells were treated with IR in the presence of MG132 (to equalize MDMX and p53 levels), MDMX coprecipitation with p53 was significantly reduced, whereas MDM2-p53 binding was nearly unchanged (Fig. 9a). Inhibition of MDMX-p53 binding by IR was dependent on Chk2, since HCT116-Chk2−/− cells did not downregulate MDMX-p53 binding (Fig. 9a). The results suggest that in addition to promoting MDMX degradation, DNA damage also inhibits MDMX-p53 binding to stimulate p53 activity.

Fig 9.

DNA damage inhibits MDMX-p53 binding. (a) HCT116 cells were treated with 10 Gy IR in the presence of MG132 (to normalize protein levels). MDMX-p53 binding was determined by p53 IP using Pab1801 and MDMX Western blotting using a polyclonal antibody. Western blots of whole-cell extract (WCE) show the expression levels of each protein. (b and c) Glutathione-agarose beads loaded with GST-p53 or GST-MDM2 were incubated with extract of control and irradiated HCT116 cells (treated with MG132). The captured MDMX was analyzed by gradient gel SDS-PAGE and MDMX Western blotting. GST-p53 selectively captured nonphosphorylated MDMX (b), and GST-MDM2 specifically captured phosphorylated MDMX (c). (d) A model of MDMX intramolecular autoinhibition and regulation by DNA damage. The central acidic region of MDMX interacts with the N-terminal domain through p53 mimicry, thus reducing p53 binding affinity. CK1α interaction with the central region and phosphorylation of S289 disrupts the intramolecular interaction, allowing the N-terminal domain to bind p53 and inhibit p53 transcriptional function. After DNA damage, phosphorylation of S367 by Chk2 inhibits CK1α-MDMX interaction, thus releasing p53 to activate transcription.

To test whether MDMX C-terminal phosphorylation reduces binding affinity to p53 independent of subcellular localization, GST-p53 was used to pull down MDMX from cell extract. C-terminal phosphorylated MDMX from irradiated cells migrates slower than nonphosphorylated MDMX on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 9b, compare lanes 2 and 3) (5), making it possible to directly compare their p53 binding affinities. The results showed that GST-p53 selectively captured nonphosphorylated MDMX (fast-migrating form) from a mixture containing both forms (Fig. 9b, compare lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, GST-MDM2 specifically pulled down phosphorylated MDMX (slow-migrating form) (Fig. 9c, compare lanes 3 and 4). Therefore, phosphorylation of MDMX on C-terminal Chk2 and ATM sites stimulates binding to MDM2 but inhibits binding to p53.

DISCUSSION

Genetic studies showed that MDMX is an important regulator of p53. We previously identified CK1α as a near-stoichiometric binding partner of MDMX that cooperates with MDMX to inhibit p53. The results of this study provide several novel insights on the function and regulation of MDMX and reveal important roles of MDMX-CK1α interaction. (i) The p53 binding domain of MDMX is negatively regulated by the central region through an intramolecular interaction. (ii) CK1α stimulates MDMX-p53 binding by disrupting the MDMX intramolecular interaction. (iii) DNA damage-mediated MDMX phosphorylation blocks MDMX-CK1α interaction, thus inhibiting MDMX-p53 binding.

The results led to the following model of MDMX-CK1α interaction (Fig. 9d). The central acidic domain of MDMX can interact with the N-terminal p53 binding pocket and prevent binding to p53, thus acting as an autoinhibitory domain. CK1α binding to the central domain and phosphorylation of MDMX at S289 disrupts the pocket-central domain interaction, allowing the pocket to bind p53 with high affinity. DNA damage inhibits MDMX-CK1α interaction through Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of S367, which in turn reduces MDMX-p53 binding affinity. Therefore, DNA damage regulates both MDMX ubiquitination and MDMX-p53 binding affinity to activate p53 transcriptional function.

Recent studies have implicated CK1α and CK1δ in phosphorylating MDM2 and regulating p53 degradation (15, 16). Our results underscore the important role of CK1α in regulating p53 activity through forming a stable complex with MDMX. We showed previously that MDMX-CK1α interaction is highly efficient compared to that of MDM2 (6). The role of this strong binding is still unknown, since most kinases do not stably associate with substrates after phosphorylation. In the case of CK1α-MDMX interaction, CK1α kinase activity and the presence of phosphorylation target residue S289 on MDMX are both necessary for regulation of p53 (6). Stable binding between MDMX and CK1α is not sufficient for regulation, because the S289A mutant has a compromised response to CK1α. It is possible that stable CK1α-MDMX interaction is required to induce conformational change in MDMX to activate the p53 binding pocket. Atomic structures have been determined for the N-terminal p53 binding domain and C-terminal RING domain of MDMX (18, 29, 39, 41, 43). The structure of the MDMX central domain, including the acidic region and zinc finger, remains unsolved. The results in this study suggest that different domains of MDMX functionally communicate through allosteric or direct contacts, providing the basis for coordinated activation of p53 after DNA damage. Phosphorylation of S367 by Chk2 has been shown to create a 14-3-3 binding site, activate a cryptic nuclear localization signal in the MDMX RING domain, and promote MDMX ubiquitination by MDM2 (22, 36). A previous study suggested that S367 phosphorylation prevents MDMX-HAUSP interaction, thus increasing MDMX ubiquitination and degradation (34). Our results showed that S367 phosphorylation significantly increases MDMX binding to MDM2, revealing an alternative mechanism leading to MDMX degradation after DNA damage. The results also revealed that CK1α-MDMX binding is regulated by S367 phosphorylation, suggesting that S367 controls the conformations of multiple MDMX domains.

What is the nature of the intramolecular autoinhibition that allows S367 to regulate the p53 binding domain? We clearly detected specific interaction between the separately expressed N-terminal domain (residues 1 to 120) and central domain (residues 100 to 361) of MDMX in vitro. This suggests that there is substantial intramolecular interaction when the two domains are linked through a flexible linker (residues 121 to 180) in the full-length protein. The sequence between residues 200 and 300 appears to be necessary for regulating the N-terminal domain. The ability of a pocket binding peptide to disrupt MDMX N-terminal central domain binding suggests that the interaction is mediated by the p53 binding pocket and a p53-mimetic structure in the central region. Examination of the sequence from residues 200 to 300 did not reveal obvious similarity to the p53 N terminus (containing the FXXXWXXL triad) (21). It is possible that one or more imperfect p53 mimic sequences located between residues 200 and 300 are involved in weak binding to the N-terminal pocket. The weak binding is compensated for by high local concentration due to the intramolecular nature of the interaction, thus creating a functionally relevant competition for p53. CK1α binding and phosphorylation of S289 may eliminate the competition, freeing the N-terminal pocket to interact with p53.

The model described in Fig. 9d shows many similarities between MDMX and MDM2 regarding their interdomain relationships. In the case of MDM2, we showed that phosphorylation of ATM sites near the RING domain inhibits RING homodimerization (8). Furthermore, phosphorylation of the ATM sites inhibits the binding between the MDM2 acidic domain and p53 core domain, suggesting that the MDM2 acidic domain conformation is regulated by the C-terminal ATM sites (8). There is also evidence that the p53 binding pocket of MDM2 allosterically communicates with the acidic domain, such that interaction of the MDM2 N-terminal pocket with the p53 N terminus stimulates a second-site interaction between the MDM2 acidic domain and the p53 core (50). Furthermore, recent study showed that a point mutation in the MDM2 RING domain causes a conformational change in the acidic domain and increases the binding affinity of the N-terminal pocket for p53 (53). Evidently, the C-terminal phosphorylation sites on MDM2 and MDMX regulate the conformation of multiple domains, which explain their strong impact on p53.

Our previous study showed that CK1α knockdown activates p53 in cell culture and cooperates with DNA damage to induce cell death (6). Under physiological conditions, CK1α has a more complex role in tumor development. A recent mouse model with tissue-specific knockout of CK1α in the intestine showed that CK1α depletion triggers p53 activation, induces cellular senescence, and suppresses cell invasion (9). However, CK1α depletion also results in stabilization of the oncoprotein β-catenin, increased proliferation, and activation of DNA damage signaling. Therefore, the in vivo results are consistent with CK1α playing a role in suppressing p53 function through interacting with MDMX, but the p53 activation after CK1α depletion may involve additional mechanisms, such as oncogenic stress and DNA damage signaling.

In summary, different domains of MDM2 and MDMX appear to have substantial intramolecular interactions through direct binding or allosteric mechanisms. These interactions may serve important roles in communicating stress-induced phosphorylation signals to cause stabilization and activation of p53 while promoting MDMX degradation. Interestingly, such a regulatory mechanism is remarkably similar to the regulation of retinoblastoma protein-E2F1 interaction by phosphorylation (2). Given the evidence that CK1α regulates p53 transcriptional activity through MDMX, inhibition of CK1α kinase activity may be beneficial to cancer treatment, particularly in tumors with MDMX overexpression and wild-type p53.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Moffitt Molecular Genomics Core for DNA sequence analyses.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to J.C. (CA141244 and CA109636).

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Banin S, et al. 1998. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science 281:1674–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke JR, Deshong AJ, Pelton JG, Rubin SM. 2010. Phosphorylation-induced conformational changes in the retinoblastoma protein inhibit E2F transactivation domain binding. J. Biol. Chem. 285:16286–16293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chehab NH, Malikzay A, Appel M, Halazonetis TD. 2000. Chk2/hCds1 functions as a DNA damage checkpoint in G(1) by stabilizing p53. Genes Dev. 14:278–288 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Marechal V, Levine AJ. 1993. Mapping of the p53 and mdm-2 interaction domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4107–4114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L, Gilkes DM, Pan Y, Lane WS, Chen J. 2005. ATM and Chk2-dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. EMBO J. 24:3411–3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L, Li C, Pan Y, Chen J. 2005. Regulation of p53-MDMX interaction by casein kinase 1 alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:6509–6520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng Q, Chen L, Li Z, Lane WS, Chen J. 2009. ATM activates p53 by regulating MDM2 oligomerization and E3 processivity. EMBO J. 28:3857–3867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Q, et al. 2011. Regulation of MDM2 E3 Ligase activity by phosphorylation after DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31:4951–4963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elyada E, et al. 2011. CKIalpha ablation highlights a critical role for p53 in invasiveness control. Nature 470:409–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francoz S, et al. 2006. Mdm4 and Mdm2 cooperate to inhibit p53 activity in proliferating and quiescent cells in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:3232–3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gajjar M, et al. 2012. The p53 mRNA-Mdm2 interaction controls Mdm2 nuclear trafficking and is required for p53 activation following DNA damage. Cancer Cell 21:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilkes DM, Chen L, Chen J. 2006. MDMX regulation of p53 response to ribosomal stress. EMBO J. 25:5614–5625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grier JD, Xiong S, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Parant JM, Lozano G. 2006. Tissue-specific differences of p53 inhibition by Mdm2 and Mdm4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:192–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu B, Gilkes DM, Chen J. 2007. Efficient p53 activation and apoptosis by simultaneous disruption of binding to MDM2 and MDMX. Cancer Res. 67:8810–8817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huart AS, MacLaine NJ, Meek DW, Hupp TR. 2009. CK1alpha plays a central role in mediating MDM2 control of p53 and E2F-1 protein stability. J. Biol. Chem. 284:32384–32394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inuzuka H, et al. 2010. Phosphorylation by casein kinase I promotes the turnover of the Mdm2 oncoprotein via the SCF(beta-TRCP) ubiquitin ligase. Cancer Cell 18:147–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones SN, Roe AE, Donehower LA, Bradley A. 1995. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature 378:206–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallen J, et al. 2009. Crystal structures of human MdmX (HdmX) in complex with p53 peptide analogues reveal surprising conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 284:8812–8821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawai H, et al. 2003. DNA damage-induced MDMX degradation is mediated by MDM2. J. Biol. Chem. 278:45946–45953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knippschild U, et al. 2005. The casein kinase 1 family: participation in multiple cellular processes in eukaryotes. Cell Signal. 17:675–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kussie PH, et al. 1996. Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science 274:948–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeBron C, Chen L, Gilkes DM, Chen J. 2006. Regulation of MDMX nuclear import and degradation by Chk2 and 14-3-3. EMBO J. 25:1196–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Cheng Q, Li Z, Chen J. 2010. p53 inactivation by MDM2 and MDMX negative feedback loops in testicular germ cell tumors. Cell Cycle 9:1411–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Chen L, Chen J. 2002. DNA damage induces MDMX nuclear translocation by p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7562–7571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Gu W. 2011. A critical role for noncoding 5S rRNA in regulating Mdmx stability. Mol. Cell 43:1023–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, et al. 2012. Abnormal MDMX degradation in tumor cells due to ARF deficiency. Oncogene 31:3721–3732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linares LK, Hengstermann A, Ciechanover A, Muller S, Scheffner M. 2003. HdmX stimulates Hdm2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:12009–12014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linares LK, Scheffner M. 2003. The ubiquitin-protein ligase activity of Hdm2 is inhibited by nucleic acids. FEBS Lett. 554:73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linke K, et al. 2008. Structure of the MDM2/MDMX RING domain heterodimer reveals dimerization is required for their ubiquitylation in trans. Cell Death Differ. 15:841–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maetens M, et al. 2007. Distinct roles of Mdm2 and Mdm4 in red cell production. Blood 109:2630–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marine JC, Jochemsen AG. 2005. Mdmx as an essential regulator of p53 activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331:750–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maya R, et al. 2001. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Mdm2 on serine 395: role in p53 activation by DNA damage. Genes Dev. 15:1067–1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayo LD, Turchi JJ, Berberich SJ. 1997. Mdm-2 phosphorylation by DNA-dependent protein kinase prevents interaction with p53. Cancer Res. 57:5013–5016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meulmeester E, et al. 2005. Loss of HAUSP-mediated deubiquitination contributes to DNA damage-induced destabilization of Hdmx and Hdm2. Mol. Cell 18:565–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montes de Oca Luna R, Wagner DS, Lozano G. 1995. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature 378:203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okamoto K, et al. 2005. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of MdmX at serine 367 activates p53 by targeting MdmX for Mdm2-dependent degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:9608–9620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan Y, Chen J. 2003. MDM2 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of MDMX. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:5113–5121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parant J, et al. 2001. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm4-null mice by loss of Trp53 suggests a nonoverlapping pathway with MDM2 to regulate p53. Nat. Genet. 29:92–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pazgier M, et al. 2009. Structural basis for high-affinity peptide inhibition of p53 interactions with MDM2 and MDMX. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:4665–4670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pereg Y, et al. 2005. Phosphorylation of Hdmx mediates its Hdm2- and ATM-dependent degradation in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:5056–5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phan J, et al. 2010. Structure-based design of high affinity peptides inhibiting the interaction of p53 with MDM2 and MDMX. J. Biol. Chem. 285:2174–2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips A, et al. 2010. HDMX-L is expressed from a functional p53-responsive promoter in the first intron of the HDMX gene and participates in an autoregulatory feedback loop to control p53 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285:29111–29127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popowicz GM, Czarna A, Holak TA. 2008. Structure of the human Mdmx protein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Cell Cycle 7:2441–2443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shieh SY, Ahn J, Tamai K, Taya Y, Prives C. 2000. The human homologs of checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Cds1 (Chk2) phosphorylate p53 at multiple DNA damage-inducible sites. Genes Dev. 14:289–300 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shieh SY, Ikeda M, Taya Y, Prives C. 1997. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell 91:325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shinozaki T, Nota A, Taya Y, Okamoto K. 2003. Functional role of Mdm2 phosphorylation by ATR in attenuation of p53 nuclear export. Oncogene 22:8870–8880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sionov RV, et al. 2001. c-Abl regulates p53 levels under normal and stress conditions by preventing its nuclear export and ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:5869–5878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terzian T, et al. 2007. Haploinsufficiency of Mdm2 and Mdm4 in tumorigenesis and development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:5479–5485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vousden KH, Lane DP. 2007. p53 in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace M, Worrall E, Pettersson S, Hupp TR, Ball KL. 2006. Dual-site regulation of MDM2 E3-ubiquitin ligase activity. Mol. Cell 23:251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, Wang J, Jiang X. 2011. MdmX protein is essential for Mdm2 protein-mediated p53 polyubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 286:23725–23734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang YV, Leblanc M, Wade M, Jochemsen AG, Wahl GM. 2009. Increased radioresistance and accelerated B cell lymphomas in mice with Mdmx mutations that prevent modifications by DNA-damage-activated kinases. Cancer Cell 16:33–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wawrzynow B, et al. 2009. A function for the RING finger domain in the allosteric control of MDM2 conformation and activity. J. Biol. Chem. 284:11517–11530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu X, Bayle JH, Olson D, Levine AJ. 1993. The p53-mdm-2 autoregulatory feedback loop. Genes Dev. 7:1126–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiong S, Van Pelt CS, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Liu G, Lozano G. 2006. Synergistic roles of Mdm2 and Mdm4 for p53 inhibition in central nervous system development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:3226–3231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu GW, et al. 2006. The central region of HDM2 provides a second binding site for p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:1227–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]