Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with numerous liver diseases and causes serious global health problems, but the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of HCV infections remain largely unknown. In this study, we demonstrate that signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) are significantly stimulated in HCV-infected patients. We further show that HCV activates STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK), and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in infected Huh7.5.1 cells. Functional screening of HCV proteins revealed that nonstructural protein 4B (NS4B) is responsible for the activation of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 by stimulating STAT3 through repression of the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3). Our results also demonstrate that multiple signaling cascades, including several members of the protein kinase C (PKC) family, JNK, ERK, and STAT3, play critical roles in the activation of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 mediated by NS4B. Further studies revealed that the C-terminal domain (CTD) of NS4B is sufficient for the activation of STAT3, JNK, ERK, MMP-2, and Bcl-2. We also show that amino acids 227 to 250 of NS4B are essential for regulation of STAT3, JNK, ERK, MMP-2, and Bcl-2, and among them, three residues (237L, 239S, and 245L) are crucial for this regulation. Thus, we reveal a novel mechanism underlying HCV pathogenesis in which multiple intracellular signaling cascades are cooperatively involved in the activation of two important cellular factors, MMP-2 and Bcl-2, in response to HCV infection.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) persistent infection is a major cause of chronic liver diseases, including hepatic steatosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which affect approximately 200 million people worldwide (12, 36, 38). However, the mechanisms by which HCV infection causes chronic human liver diseases remain largely unknown. HCV is a small and enveloped RNA virus belonging to the Hepacivirus genus of the Flaviviridae family (26). The HCV genome consists of a single-stranded positive-sense RNA of approximately 9.6 kb that contains a single open reading frame encoding a polyprotein precursor of approximately 3,000 residues. The polyprotein precursor is then cleaved into at least 10 distinct proteins, including 4 structural proteins (core, E1, E2, and p7) and 6 nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) (52).

Signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) are a family of cytoplasmic proteins with Src homology-2 (SH2) domains that act as signal messengers and transcription factors and participate in normal cellular responses to cytokines and growth factors (GFs). After stimulation of cytokine-receptor complexes and GF-receptor complexes following ligand binding, STATs are activated via the tyrosine phosphorylation cascade (40, 59, 66). Among the STAT proteins characterized to date, STAT3 has been implicated in the transduction of cellular signals involved in the development of cardiac hypertrophy and in the induction of gene expression in response to cytokine receptor stimulation (20, 40). After tyrosine phosphorylation, STAT3 is dimerized and translocated to the nucleus, where it activates downstream target genes (20, 40), including c-Fos, cyclin D1 (CCND1), cell division cycle 25A (CDC25A), c-Myc, proviral integration site 1 (Pim1), and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) (5). Bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis and contributes to cell survival and the resistance of cells against damaging influences (23). The Bcl-2-related genes regulate cell death and are considered to correlate with the pathogenesis and progression of cancers (15, 28, 63). STAT3 also promotes metastasis and angiogenesis by inducing expression of a metastatic gene, matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), as well as a potent angiogenic gene, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (15). STAT3 activation is often associated with cell growth or transformation, and disruption of STAT3 causes embryonic lethality.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) play important roles in viral infection. In multicellular organisms, there are three well-characterized subfamilies of MAPKs, including the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs; ERK1 and ERK2), the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs; JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3), and the p38 enzymes (p38α, p38β, p38γ, and p38δ). The JNK and ERK pathways have been implicated in relaying extracellular signals to the nucleus to mediate specific responses, such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and stress, by regulating transcription factor activity (25, 33, 53). It has been reported that the cooperation of tyrosine and serine phosphorylation is necessary for the full activation of STAT3 (4, 9, 61). Members of the suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family negatively regulate STAT3 activity.

Members of the protein kinase C (PKC) superfamily play key regulatory roles in many cellular processes, ranging from the control of fundamental cell autonomous activities (such as proliferation) to more organismal functions (such as memory). These kinases can be activated by phosphatidylserine (PS) and diacylglycerol (DAG) in a Ca2+-dependent manner and also by tumor-promoting phorbol esters such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (46). PKCα-mediated ERK, JNK, and p38 regulate the myogenic program in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells (45).

Our previous studies have shown that HCV infection activates the Ras/Raf/MEK pathway, which in turn facilitates HCV replication via attenuation of the interferon (IFN)-JAK-STAT pathway (67). We also demonstrated that HCV infection activates the expression of the major vault protein (MVP), which is involved in multidrug resistance, nucleocytoplasmic transport, and cell signaling through the NF-κB and Sp1 pathways (42). More interestingly, virus-activated MVP can suppress HCV replication by inducing type I IFN expression (42). These findings suggested that HCV infection activates multiple cellular signaling pathways. Thus, in this study we investigated the signal transduction networks regulated by HCV infection and the molecular mechanisms underlying such regulation.

Here, we found that STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 were significantly stimulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from patients with HCV infection and in cell cultures infected with HCV. In addition, we demonstrated that HCV regulates MMP-2 and Bcl-2 by activating the STAT3 signaling cascade. Further studies revealed that the ERK, JNK, and PKC signaling pathways are involved in the upregulation of STAT3 activity in response to HCV infection. We also discuss the mechanism underlying the role of HCV NS4B in controlling multiple signaling pathways and in the regulation of genes involved in cell transformation, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis in response to HCV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood specimens.

Peripheral blood specimens were obtained from 20 patients with chronic HCV infection in Yunnan Province, China (Table 1). All patients were confirmed to be HCV positive and were negative for concomitant HBV, HDV, or HIV infection. They did not suffer any concomitant disease at the moment of sampling, did not show any serological markers suggestive of autoimmune disease, and had not received any antiviral or immunomodulatory therapy prior to this study. Matched by sex and age, 20 HCV-negative individuals with no history of liver disease were randomly selected from a local blood donation center as controls. The Institutional Review Board of the College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, approved the collection of blood samples for this research, in accordance with guidelines for the protection of human subjects. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of HCV-negative individuals and HCV-positive patientsa

| Characteristic | HCV-negative individuals | HCV-positive individuals |

|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 20 | 20 |

| No. of males/no. of females | 12/8 | 9/11 |

| Age (yr) | 35 ± 14 | 37 ± 7 |

| AST concn (U/liter) | 25 ± 13 | 68.3 ± 14 |

| ALT concn (U/liter) | 21 ± 14 | 44 ± 8.5 |

| T-BIL concn (μmol/liter) | 7.6 ± 1.7 | 32.7 ± 14 |

| No. of HCV RNA copies | NA | 3.0E+07 ± 2.1E+06 |

| No. of patients infected with HCV genotype 1b/genotype 3b | NA | 13/7 |

All HCV-positive individuals were confirmed to be negative for HBV, HDV, and HIV-1, were not suffering from any concomitant illness, did not show any serological markers suggestive of autoimmune disease, and had not received any antiviral or immunomodulatory therapy prior to this study. Matched by sex and age, 20 HCV-negative individuals with no history of liver disease were randomly selected as controls. AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; T-BIL, total bilirubin; NA, not applicable.

Isolation of PBMCs.

PBMCs were obtained by density centrifugation of peripheral blood samples diluted 1:1 in pyrogen-free saline over Histopaque (Haoyang Biotech). Cells were washed twice in saline and suspended in culture medium (RPMI 1640) supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml).

Plasmids.

Plasmid pGL3-APRE-luc, in which the reporter gene is under the control of the STAT3 gene promoter, was obtained from Li Liu of Tsinghua University, China. Plasmids expressing small interfering RNA (siRNA) against STAT3 and members of the protein kinase C (PKC) family were constructed by ligating corresponding pairs of oligonucleotides based on target sequences described previously (41, 43) to pSilencer2.1-U6 neo (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX). The siRNAs against SOCS3, JNK, and ERK (si-SOCS3, si-JNK, and si-ERK, respectively) and the siRNA control (si-Ctrl) used in our study were synthesized by the Ribobio Company and purchased directly from the Ribobio Company. ERK1 and ERK2 mutants (mERK1 and mERK2) were gifts from Melanie Cobb of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, while the JNK mutant (mJNK) was from Michael Karin of the University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA (41, 43). V12 encoding activated hemagglutinin (HA)-Ras was cloned into pCMV-Tag2A vector (Stratagene) as described previously (67). Plasmids expressing HCV genotype 2a proteins were generated in the State Key Laboratory of Virology, Wuhan University, as described previously (42). Truncated NS4B genes were generated by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using HCV RNA as the template. The amplified DNA fragments were subcloned into pCMV-Tag2A to generate plasmids pCMV-NS4BCTD, pCMV-NS4BΔC1, pCMV-NS4BΔC2, and pCMV-NS4BΔC3. Mutated NS4B genes (D228A, L237E, S239W, T241A, L245D, and H250E) were constructed by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis using plasmid pCMV-NS4B as the template. In these mutated NS4B genes, amino acids 228D, 237L, 239S, 241T, 245L, and 250H were replaced by 228A, 237E, 239W, 241A, 245D, and 250E, respectively. All constructs were verified by automatic DNA sequencing. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in these studiesa

| Mutation | Orientation | Restriction site | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| D228A | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-TACGTGACGGAGTCGGCTGCGTCGCAGCGTGT-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-ACACGCTGCGACGCAGCCGACTCCGTCACGTA-3′ | |

| L237E | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-CGTGTGACCCAACTAGAGGGCTCTCTTACTATAACC-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-GGTTATAGTAAGAGAGCCCTCTAGTTGGGTCACACG-3′ | |

| S239W | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-GACCCAACTACTTGGCTGGCTTACTATAACCAG-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-CTGGTTATAGTAAGCCAGCCAAGTAGTTGGGTC-3′ | |

| T241A | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-ACTACTTGGCTCTCTTGCAATAACCAGCCTACT-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-AGTAGGCTGGTTATTGCAAGAGAGCCAAGTAGTT-3′ | |

| L245D | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-TCTTACTATAACCAGCGACCTCAGAAGACTCCAC-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-GTGGAGTCTTCTGAGGTCGCTGGTTATAGTAAGA-3′ | |

| H250E | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-CTACTCAGAAGACTCGAGAATTGGATAACTGAGG-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-CCTCAGTTATCCAATTCTCGAGTCTTCTGAGTAG-3′ | |

| △C1 | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-GGAGAATTCCGCCTCTAGGGCGGCTCT-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-CACAAGCTTCTACAGAATGGCCGCGCAGATGA-3′ | |

| CTD | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-GGCGAATTCGCGCCGCCACGTG-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-CCAAAGCTTCTAGCATGGGATGGGGCAGTCC-3′ | |

| △C2 | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-GGAGAATTCCGCCTCTAGGGCGGCTCT-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-CGAAAGCTTCTACTCCGTCACGTAGTGAGTAGGGG-3′ | |

| △C3 | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-GGAGAATTCCGCCTCTAGGGCGGCTCT-3′ |

| Rev | XholI | 5′-AGTCTCGAGCTAGTGGAGTCTTCTGAGTAGGCTGG-3′ | |

| NS4B | Fwd | EcoRI | 5′-GGAGAATTCCGCCTCTAGGGCGGCTCT-3′ |

| Rev | HindIII | 5′-CCAAAGCTTCTAGCATGGGATGGGGCAG-3′ | |

| STAT3 | Fwd | 5′-GGAGGAGGCATTCGGAAG-3′ | |

| Rev | 5′-ATCTGTGTGACACCAACGA-3′ | ||

| MMP-2 | Fwd | 5′-CCACTGCCTTCGATACAC-3′ | |

| Rev | 5′-GAGCCACTCTCTGGAATCTTAAA-3′ | ||

| Bcl-2 | Fwd | 5′-TCCCTCGCTGCACAAATACTC-3′ | |

| Rev | 5′-TTCTGCCCCTGCCAAATCT-3′ | ||

| SOCS3 | Fwd | 5′-TGCCTCCTGACTATGTCTGGCTAA-3′ | |

| Rev | 5′-AGTGGGGACCTGGTGGCTCTGCTC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | Fwd | 5′-AAGGCTGTGGGCAAGG-3′ | |

| Rev | 5′-TGGAGGAGTGGGTGTCG-3′ | ||

| si-SOCS3 | Fwd | 5′-CACCUGGACUCCUAUGAGAdTdT-3′ | |

| Rev | 5′-dTdTGUGGACCUGAGGAUACUCU-3′ | ||

| si-JNK | Fwd | 5′-GCCCAGUAAUAUAGUAGAUdTdT-3′ | |

| Rev | 5′-dTdTCGGGUCAUUAUAUCAUCAU-3′ | ||

| si-ERK | Fwd | 5′-CAAGAAGACCUGAAUUGUAdTdT-3′ | |

| Rev | 5′-dTdTGUUCUUCUGGACUUAACAU-3′ | ||

| F1outer | Fwd | 5′-GCAACAGGGAACCTTCCTGGTTGCTC-3′ | |

| R1outer | Rev | 5′-CGTAGGGGCCAGTTCATCATCATCATCAT-3′ | |

| F1inner | Fwd | 5′-AACCTTCCTGGTTGCTCTTTCTCTAT-3′ | |

| R1inner | Rev | 5′-GTTCATCATCATATCCCATGCCAT-3′ |

Mutated nucleotides are in boldface. D228A, L237E, S239W, T241A, H250, and H250E, point mutations of HCV NS4B; △C1, △C2, and △C3, truncations of HCV NS4B; CTD, carboxy-terminal domain of the NS4B protein; Fwd, forward primers; Rev, reverse primers; NS4B, wild-type NS4B protein of HCV; STAT3, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the signal transducer and activators of transcription 3; MMP-2, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the matrix metalloproteinase-2; Bcl-2, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the B-cell lymphoma 2; SOCS3, semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3; GAPDH, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; si-SOCS3, si-JNK, and si-ERK, siRNAs against SOCS3, JNK, and ERK, respectively, were purchased directly from Ribobio Company; F1outer, outer sense primer from the 5′ noncoding region of the HCV(493 to 518 nucleotides); R1outer, outer antisense primer from the 5′ noncoding region of the HCV genome (987 to 964 nucleotides); F1inner, inner sense primer from the 5′noncoding region of the HCV genome (502 to 527 nucleotides); R1inner, inner antisense primer from the 5′ noncoding region of the HCV genome (975 to 952 nucleotides).

Antibodies and reagents.

Antibodies against ERK (sc-153), phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) (sc-7383), phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK) (sc-7988), STAT3 (sc-476), MMP-2 (sc-13594), and Bcl-2 (sc-7382) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibody against HCV NS3 (ab65407) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). Antibodies against p-STAT3 (9145) and JNK (9252) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against β-actin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were purchased from CWBio (Beijing CoWin Biotech, China). The protein kinase inhibitors (U0126 and SP100625) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, United Kingdom) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) upon use.

Cells and viruses.

Huh7.5.1 cells were kindly provided by Francis Chisari. Huh7.5.1 and Huh7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. HCV genotype 2a strain JFH-1 was kindly provided by Takaji Wakita. Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with JFH-1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of between 0.1 and 5. HCV was propagated for 6 days before collection. Virus stock was obtained after filtering of the cell supernatant. Viral titers were quantified using a commercial kit (HCV RNA qPCR diagnostic kit; KHB Company, Shanghai, China). Aliquots were stored at −80°C prior to use.

Transient-transfection and luciferase assays.

Cells were seeded in 24-well dishes and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 24 h and then serum starved for an additional 24 h prior to harvest. Renilla luciferase plasmid pRL-TK was used as an internal control. Luciferase assays were performed with a dual-luciferase kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis and nested PCR.

Total RNA was extracted by the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed with random primers. Real-time PCR was performed with a LightCycler 480 apparatus (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with GAPDH as the internal control. To generate the HCV RNA references for determination of the sensitivity and specificity of the strand-specific RT-PCR, RNA was extracted from the patients' PBMCs. Subsequently, RNA was retrotranscribed with primers specific for the 5′ untranslated region of HCV (antisense primer R1outer for the plus RNA strand and sense primer F1outer for the minus RNA strand). A nested PCR was then performed using two different primer sets: F1outer and R1outer in the first step and F1inner and R1inner in the second step. The amplified product (474 bp) was visualized on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. Primers used for the quantitative RT-PCR and nest-PCR analysis are listed in Table 2.

MMP zymography.

The collagenolytic activity was determined on a gelatin-impregnated (1 mg/ml; Difco, Detroit, MI) 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Protein samples were separated under nonreducing conditions, followed by 30 min incubation in 2.5% Triton X-100 (BDH, England). The gels were then incubated for 16 h at 37°C in 50 mM Tris, 0.2 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.02% Brij 35 (wt/vol) at pH 7.6. At the end of the incubation period, the gels were stained with 0.5% Coomassie G250 (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) in methanol-acetic acid-H2O (30:10:60). MMP-2 standards were loaded into each gel for band identification, and the proteolytic band intensities were quantified by scanning densitometry.

Nuclear extraction.

After serum starvation for 24 h, cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). They were then harvested and incubated in 2 volumes of buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 200 mM sucrose) for 5 min at 4°C with tube flipping. The crude nuclei were collected by centrifugation for 30 s; pellets were rinsed with buffer A, resuspended in 1 volume of buffer B (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 1.0 mM DTT), and incubated on a shaking platform for 30 min at 4°C. Nuclei were centrifuged for 5 min, and supernatants were collected. Cocktail protease inhibitor tablets were added to each type of buffer. Nuclear extracts were stored at −70°C before use.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and collected, and the pellets were resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM sodium formate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10% cocktail protease inhibitor). Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The protein concentration in each sample was determined using a Bradford assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cultured cell lysates (100 μg) were electrophoresed on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham). Nonspecific sites were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk before being incubated with a specific antibody. Blots were analyzed using a luminescent image analyzer (LAS-4000; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescence.

Huh7 cells grown on sterile coverslips were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or control vector at 40% confluence. After 48 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed three times with PBS, and permeabilized with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min. They were then washed three times with PBS and blocked with PBS containing 4% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the cells were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with Alexa 492-labeled secondary antibodies (ProteinTech Group) for 1 h. Mounting was done with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Laboratories), and the cells were visualized by confocal laser microscopy (Fluoview FV1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistics.

All experiments were reproducible, and each set was repeated at least three times with similar results. Parallel samples were analyzed for a normal distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Abnormal values were eliminated according to a follow-up Grubbs test. Levene's test for equality of variances was performed and provided information for Student's t test to distinguish the equality of means. Means were illustrated using a histogram with error bars representing ± the standard deviation (SD), and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

HCV stimulates STAT3 activity through regulating the JNK and ERK signaling cascades, resulting in the activation of MMP-2 and Bcl-2.

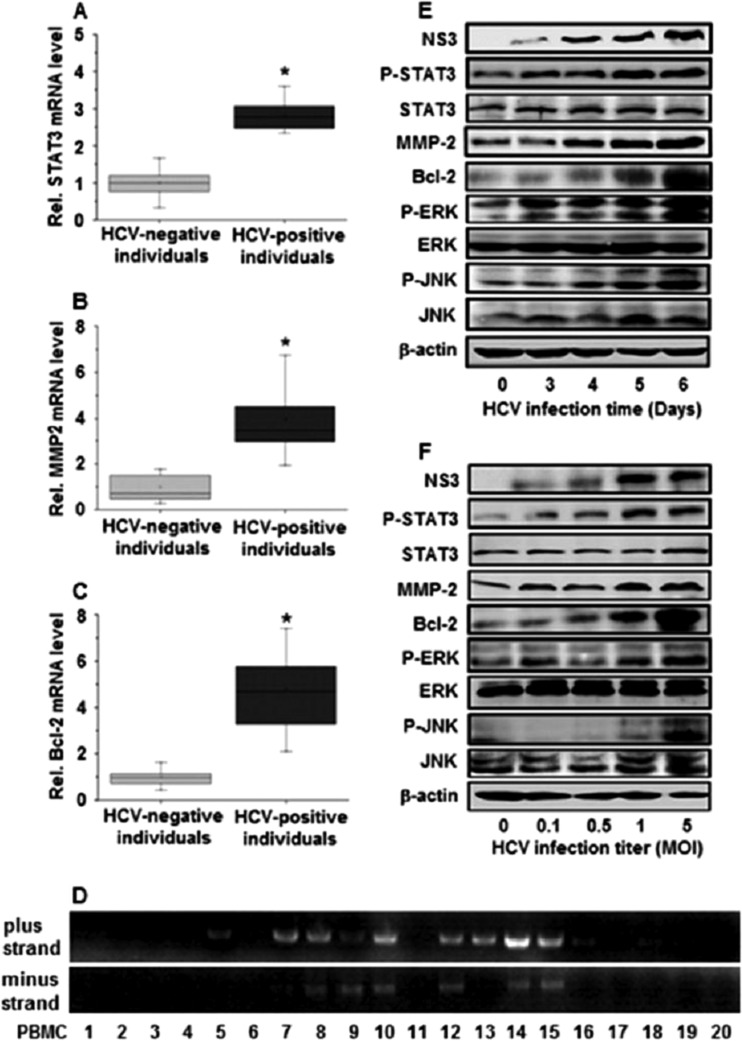

We first investigated the effect of HCV infection on the regulation of STAT3, an important protein associated with cell cycle progression, growth, transformation, metastasis, and angiogenesis. PBMCs were isolated from HCV-positive individuals (n = 20) and HCV-negative individuals (n = 20) (Table 1). Real-time RT-PCR showed that the relative mRNA levels of STAT3 were approximately 3-fold higher in HCV-positive individuals than in HCV-negative individuals (Fig. 1A), suggesting that STAT3 is activated during HCV infection. Since STAT3 is the upstream target of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 (5, 14), we examined the expression status of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 in the clinical samples. Similar to STAT3, the relative mRNA levels of MMP-2 (Fig. 1B) and Bcl-2 (Fig. 1C) were increased in HCV-positive individuals compared to HCV-negative individuals. These results demonstrate that HCV activates STAT3, resulting in the upregulation of MMP-2 and Bcl-2. HCV replication in the PBMCs of HCV patients was determined by nested PCR analyses, which showed that HCV plus-strand RNA was detected in the PBMCs of 12 of the 20 patients and minus-strand RNA was detected in the PBMCs of 7 of the 20 patients (Fig. 1D), confirming that HCV replicated in the PBMCs of HCV patients.

Fig 1.

Expression of STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, ERK, and JNK in vivo and in vitro. (A to C) PBMCs were isolated from peripheral blood samples obtained from 20 patients with HCV infection and 20 HCV-negative individuals. The mRNA levels of MMP-2, Bcl-2, and STAT3 were measured using real-time PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. MMP-2, Bcl-2, and STAT3 levels in each sample were normalized by dividing by the GAPDH quantity; *, P < 0.05; Rel., relative. (D) HCV plus- and minus-strand RNAs from the PBMCs of HCV-infected patients were detected by nested PCR using two different primer sets for the 5′ noncoding region, which is the best conserved among different HCV isolates. (E) Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with JFH-1 at an MOI of 1 for different times, as indicated. Proteins were detected by Western blot analyses using appropriate antibodies. The HCV NS3 protein level was measured to confirm HCV replication in the cells. (F) Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with JFH-1 at different titers for 6 days, as indicated. Proteins were detected by Western blot analyses using appropriate antibodies. HCV NS3 protein levels were monitored to ensure that HCV was replicating in the cells. NS3, HCV NS3 protein; p-STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3 protein; STAT3, total STAT3 protein; p-ERK, phosphorylated ERK protein; ERK, total ERK protein; p-JNK, phosphorylated JNK protein; JNK, total JNK protein.

The mechanism involved in the activation of STAT3 by HCV infection was further investigated in vitro by infecting Huh7.5.1 cells with HCV JFH-1 for different times. Western blot analyses revealed that the HCV NS3 protein was detected at 3 days postinfection, indicating that HCV replicated well in infected cells (Fig. 1E). The levels of the p-STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 proteins in infected cells were increased in a time-dependent manner, the levels of STAT3 proteins were slightly increased by 1.17-fold at 6 days postinfection, and the level of β-actin proteins remained relatively constant during HCV infection (Fig. 1E). It has been reported that phosphorylation of STAT3 is regulated by the JNK and ERK signaling cascade (4, 9, 61). We also revealed that the levels of the p-ERK and p-JNK proteins were increased over time after HCV infection, while the levels of the ERK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were relatively unchanged during HCV infection (Fig. 1E). In addition, Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with JFH-1 at different concentrations. The results showed that the levels of the NS3, p-STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, p-ERK, and p-JNK proteins were enhanced in cells infected with HCV in a dose-dependent fashion and the level of the STAT3 protein was slightly increased by 1.22-fold, while the levels of the ERK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were relatively unchanged during HCV infection (Fig. 1F). Thus, we demonstrate that HCV stimulates STAT3 activity through the JNK and ERK signaling cascades, resulting in the activation of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 in hepatocytes. These in vitro results (in Huh7.5.1 cells transiently infected with HCV) are consistent with our in vivo data (in PBMCs chronically infected with HCV).

The NS4B protein of HCV activates MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression by repressing SOCS3 production and stimulating STAT3 activity.

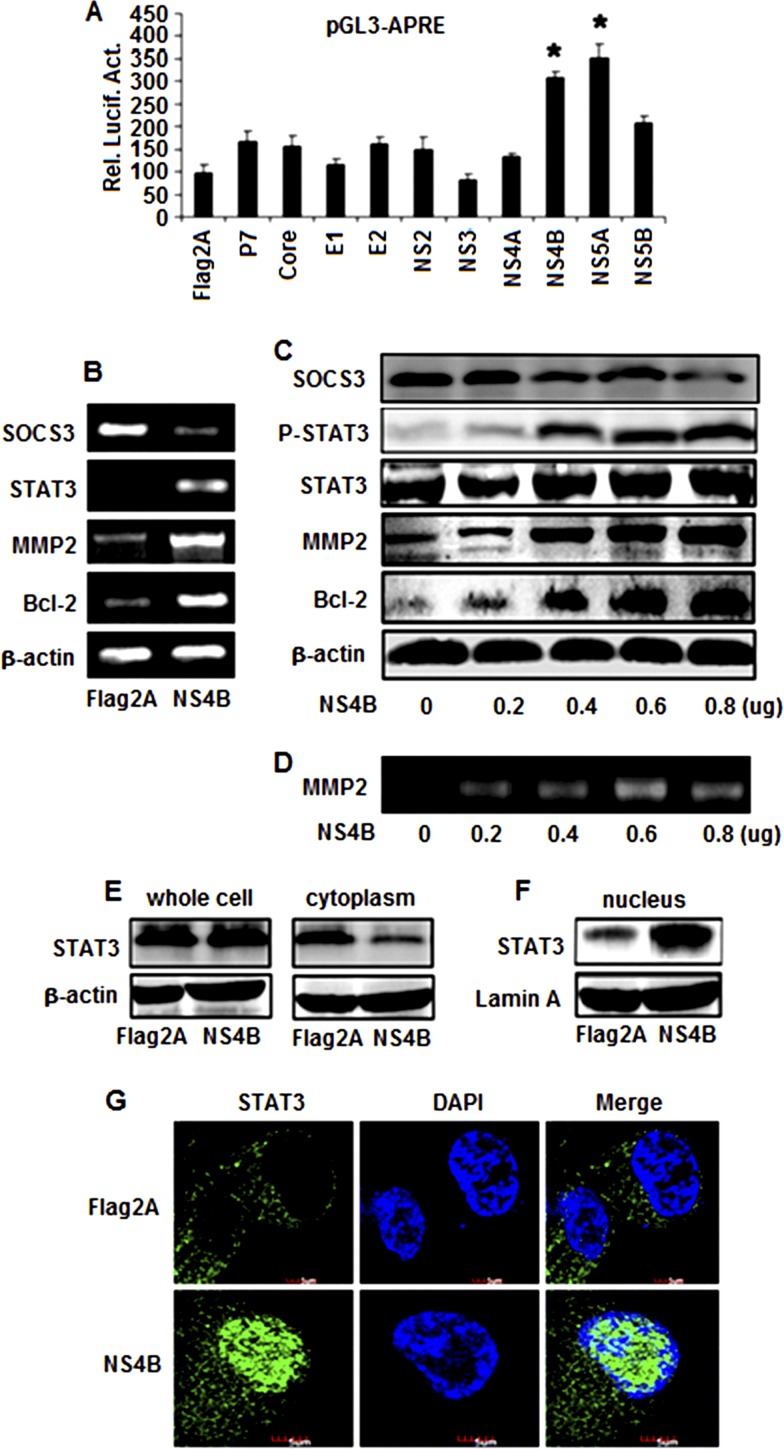

We then determined which of the 10 proteins of HCV is responsible for the regulation of STAT3. Huh7 cells were cotransfected with the reporter plasmid pGL3-APRE-Luc, along with plasmids expressing each of the 10 HCV genes constructed previously (42). A luciferase activity assay showed that STAT3 promoter activity was activated by NS4B or NS5A, while other proteins had a slight or no effect on the STAT3 promoter (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that the HCV NS4B and NS5A proteins are involved in the regulation of STAT3 expression.

Fig 2.

Effects of HCV proteins in the regulation of STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 expression. (A) Huh7 cells were cotransfected with the reporter pGL3-APRE-Luc containing the luciferase gene under the control of the STAT3 promoter and pCMV-Flag2A, pCMV-core, pCMV-E1, pCMV-E2, pCMV-P7, pCMV-NS2, pCMV-NS3, pCMV-NS4A, pCMV-NS4B, pCMV-NS5A, or pCMV-NS5B expressing the corresponding HCV proteins. Luciferase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD of independent experiments performed in triplicate and normalized using a β-galactosidase assay. *, P < 0.05 versus pCMV-Flag2A; Rel. Lucif. Act., relative luciferase activity. (B) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Flag2A. At 48 h posttransfection, total RNA was isolated and used as the template for RT-PCR using primers specific to Bcl-2, MMP-2, STAT3, SOCS3, and β-actin. (C) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B at different concentrations, as indicated. Proteins were detected by Western blot analysis using antibodies to p-STAT3, STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, SOCS3, and β-actin. (D) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Flag2A at the indicated concentrations. MMP-2 activity was measured by gelatin zymography at 48 h posttransfection. (E and F) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Flag2A. The STAT3 protein levels in whole-cell lysates, the cytoplasm, and the nucleus were determined by Western blot analysis using antibodies to STAT3. (G) Effect of NS4B on the translocation of STAT3 from the cytosol to the nucleus. Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or control vector for 48 h. After fixation, the cells were immunostained with antibody for STAT3. The nuclei were stained by DAPI.

HCV NS5A is known to activate STAT3, interact with Bax, and inhibit apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (10, 21, 55). Moreover, it has been reported that the nucleotide binding motif of hepatitis C virus NS4B can mediate cellular transformation and tumor formation without HA-Ras cotransfection (14). Thus, we explored only the role of NS4B in STAT3 activation in this study. To determine the effects of NS4B on MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression, Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Tag2A. RT-PCR results showed that STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 mRNAs were stimulated by NS4B but SOCS3 (a suppressor of STAT3) mRNA was repressed by NS4B (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that HCV NS4B activates STAT3 expression by repressing its suppressor, SOCS3.

STAT3 is activated by phosphorylation, which induces its translocation from the cytosol to nucleus to regulate target genes. We examined the effect of NS4B on the phosphorylation and translocation of STAT3. Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Tag2A at different concentrations. Results revealed that the SOCS3 protein was decreased but that in the presence of NS4B the STAT3, p-STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 proteins were increased in a dose-dependent fashion, while the STAT3 protein was slightly increased by 1.45-fold (Fig. 2C). In addition, results from gelatin zymography analyses showed that in the presence of NS4B the gelatinolytic activity of MMP-2 was increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2D). Further investigation revealed that the level of the STAT3 protein was slightly affected by NS4B in whole-cell lysates and was reduced by NS4B in the cytosol (Fig. 2E) but significantly enhanced by NS4B in the nucleus (Fig. 2F), suggesting that the HCV NS4B protein may play a role in stimulating STAT3 translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus. Moreover, immunofluorescence assays showed that the STAT3 protein was mainly located in the cytosol in the absence of NS4B but shifted its distribution to the nucleus in the presence of NS4B (Fig. 2G). These results demonstrate that NS4B activates the phosphorylation of STAT3 and promotes the translocation of STAT3 from the cytosol to the nucleus, resulting in the activation of the target genes, MMP-2 and Bcl-2.

ERK, JNK, and SOCS3 play critical roles in the regulation of STAT3 signaling mediated by NS4B.

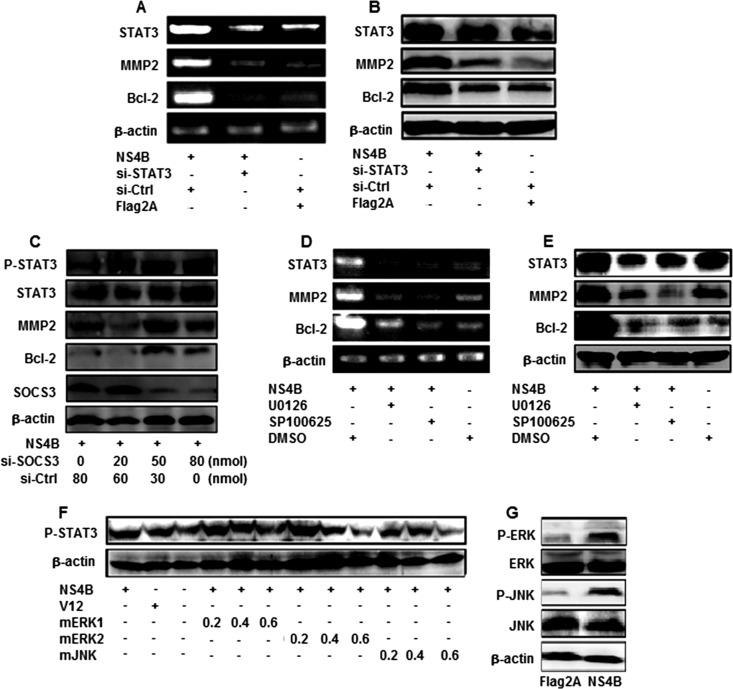

To further explore the role of STAT3 in MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression mediated by NS4B, Huh7 cells were cotransfected with pCMV-NS4B, pCMV-flag2A, si-STAT3, or si-Ctrl, as indicated. We showed that the levels of STAT3 mRNAs and protein were repressed in the presence of si-STAT3 but the levels of β-actin mRNA and protein were not affected by si-STAT3 (Fig. 3A and B), indicating that si-STAT3 is specific and effective. Results also showed that the levels of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 mRNAs and proteins were activated by NS4B but significantly reduced by si-STAT3 (Fig. 3A and B). These results suggest that overexpression of STAT3 upregulates MMP-2 and Bcl-2, while knockdown of STAT3 downregulates MMP-2 and Bcl-2, supporting the suggestion that STAT3 activates MMP-2 and Bcl-2 in the presence of HCV NS4B.

Fig 3.

Roles of SOCS3, ERK, and JNK in the regulation of STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2. (A and B) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Flag2A or treated with si-STAT3 or si-Ctrl. STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 mRNA levels were determined by RT-PCR, and TAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis. (C) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B and treated with si-SOCS3 or si-Ctrl at different concentrations, as indicated. STAT3, p-STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis. (D and E) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Flag2A and then treated with protein kinase inhibitors SP600125 and U0126. STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 mRNA levels were measured at 48 h posttransfection by RT-PCR, and STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis. The blot is a representative of three experiments with similar results. (F) Huh7 cells were cotransfected with pCMV-NS4B, V12, or dominant-negative mutants (mERK1, mERK2, and mJNK) of ERK or JNK at different concentrations, as indicated. p-STAT3 and β-actin proteins were measured by Western blot analysis. (G) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Flag2A. p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were determined by Western blot analysis.

To verify the role of SOCS3 in this regulation, Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B and treated with si-SOCS3 or si-Ctrl at different concentrations. The results indicate that while SOCS3 was reduced, the p-STAT3, STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 proteins were enhanced in the presence of si-SOCS3 in dose-dependent fashion and STAT3 and β-actin were not affected by si-SOCS3 (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that HCV NS4B activates STAT3 expression by repressing its suppressor, SOCS3.

Given the critical roles of STAT3 in liver inflammation and carcinogenesis, it is important to understand the key upstream signaling pathways involved in the regulation of STAT3 in human liver cells. It has been reported that the ERK and JNK signaling cascade regulates several transcription factors that are important in the proinflammatory response and that the regulation of STAT3 expression depends on the kinase activators in various cell types (4, 9, 61). Thus, we identified the components of cellular signaling cascades involved in the regulation of STAT3 in response to HCV infection. Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B and treated with U0126 (an ERK-specific inhibitor) and SP600125 (a JNK-specific inhibitor). The results indicate that the levels of STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 mRNA (Fig. 3D) and protein (Fig. 3E) were enhanced by NS4B but repressed by SP600125 and U0126, suggesting that ERK and JNK are involved in the regulation of STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 mediated by NS4B.

The roles of ERK and JNK in the activation of STAT3 mediated by NS4B were further evaluated by introducing three dominant kinase-inactive mutants (mERK1, mERK2, and mJNK) which block the corresponding kinase activities by competing with endogenous kinases (43). Huh7 cells were cotransfected with pCMV-NS4B V12 (a constitutively active form of Ras that activates ERK) and each of the three kinase mutants, mERK1, mERK2, and mJNK. We found that the p-STAT3 protein was activated by NS4B and V12 but repressed by mERK1, mERK2, and mJNK in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3F), demonstrating that ERK and JNK are involved in the activation of STAT3 regulated by NS4B.

To evaluate the effect of NS4B on the activation of the JNK and ERK signaling cascades, Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B or pCMV-Tag2A. The results showed that the levels of the p-ERK and p-JNK proteins were significantly enhanced by NS4B but the levels of the ERK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were unaffected by NS4B (Fig. 3G). These results suggest that NS4B plays a role in the activation of the ERK and JNK signaling pathway through phosphorylation of these two protein kinases, resulting in the activation of STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2.

Members of the PKC family are involved in activation of STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 regulated by NS4B.

It is known that members of the PKC family comprise a class of intracellular serine/threonine-specific kinases (62). Depending on the isoform, activation of PKCs is typically initiated by Ca2+, lipid second messengers, or protein activators. PKCε interacts with STAT3 and regulates its constitutive activation in prostate cancer and also sensitizes skin to UV radiation-induced cutaneous damage and the development of squamous cell carcinomas (62). PKCα activates ERK, JNK, and p38 to regulate the myogenic program in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells (45).

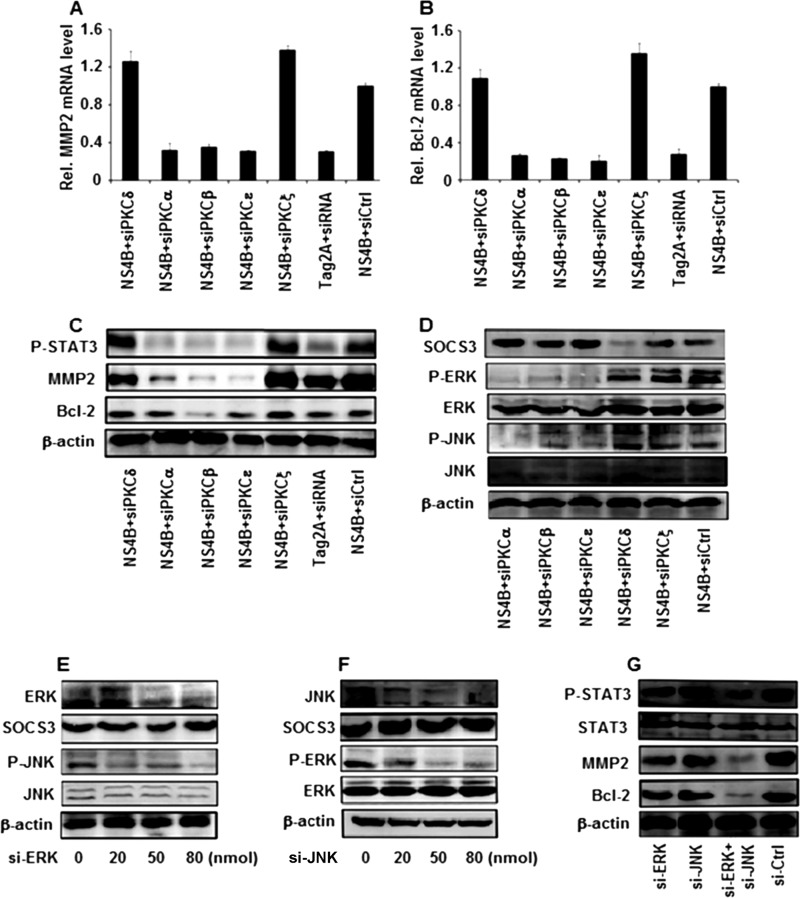

We extended our study to identify the specific PKC proteins involved in STAT3 activation regulated by NS4B. siRNA molecules specific to each of the PKC isozymes were designed and used previously (43). Huh7 cells were cotransfected with pCMV-NS4B and si-PKCδ, si-PKCα, si-PKCβ, si-PKCε, si-PKCζ, or si-Ctrl, as indicated. Results showed that MMP-2 and Bcl-2 mRNA levels were increased in the presence of NS4B, while they were repressed by si-PKCα, si-PKCβ, and si-PKCε and were not affected by si-PKCδ, si-PKCζ, or si-Ctrl (Fig. 4A and B). Similarly, p-JNK, p-ERK, p-STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 proteins were stimulated by NS4B, while they were repressed by si-PKCα, si-PKCβ, and si-PKCε and not affected by si-PKCδ, si-PKCζ, or si-Ctrl (Fig. 4C and D). These results suggest that PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCε are involved in the NS4B-mediated activation of STAT3.

Fig 4.

Effects of the members of the PKC family on the regulation of MMP-2, Bcl-2, and STAT3 mediated by HCV NS4B. (A to C) Huh7 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing si-PKCδ, si-PKCα, si-PKCβ, si-PKCε, si-PKCζ, or si-Ctrl. A similar vector (pSilencer 2.0) containing an irrelevant sequence that does not have significant homology to any human gene was provided by Ambion, Inc., and used as a negative control. The relative levels of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 mRNA were measured by real-time PCR at 48 h posttransfection, and the levels of p-STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, and β-actin proteins were determined by Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. MMP-2 and Bcl-2 levels in each sample were normalized by dividing by the GAPDH quantity. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (D) Huh7 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing si-PKCα, si-PKCβ, si-PKCε, si-PKCδ, si-PKCζ, or si-Ctrl. The levels of SOCS3, p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were determined by Western blot analysis at 48 h posttransfection. (E) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B and treated with si-ERK or si-Ctrl at the indicated concentrations, and the levels of the ERK, SOCS3, p-JNK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were determined by Western blot analysis. (F) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B and treated with si-JNK or si-Ctrl at different concentrations, as indicated. The levels of the JNK, SOCS3, p-ERK, ERK, and β-actin proteins were determined by Western blot analysis. (G) Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B and treated with si-ERK (80 nmol), si-JNK (80 nmol), or si-ERK (40 nmol) and si-JNK (40 nmol). The protein levels of p-STAT3, STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, and β-actin were determined by Western blot analysis.

The results presented above demonstrate that PKCα, PKCβ, PKCε, ERK, JNK, and SOCS3 play critical roles in the regulation of STAT3 activity medicated by the HCV NS4B protein. To further evaluate the correlation between ERK, JNK, and SOCS3, Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B and treated with si-JNK or si-ERK at different concentrations. The results indicate that the ERK and p-JNK proteins are reduced in the presence of si-ERK, while the SOCS3, JNK, and β-actin proteins are not affected by si-ERK (Fig. 4E). Equally interesting, JNK and p-ERK proteins were repressed in the presence of si-JNK, while SOCS3, ERK, and β-actin proteins were not affected by si-JNK (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, Huh7 cells were transfected with pCMV-NS4B and treated with si-ERK (80 nmol), si-JNK (80 nmol), or si-ERK (40 nmol) and si-JNK (40 nmol) (Fig. 4G). The activity of STAT3 was significantly reduced when cells were transfected with both si-JNK (40 nmol) and si-ERK (40 nmol). Results show that the two components of these pathways (ERK and JNK) have synergistic effects. Thus, these results suggest that there is a correlation between ERK and JNK but SOCS3 is independent of ERK/JNK.

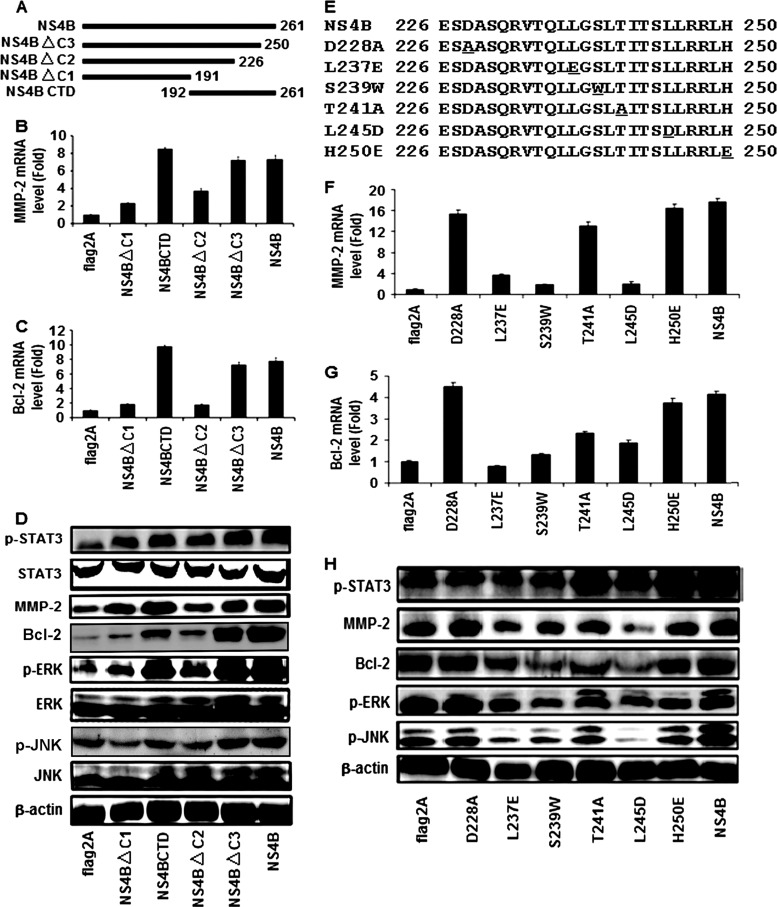

The NS4B CTD is sufficient for the activation of STAT3, JNK, ERK, MMP-2, and Bcl-2, and amino acids 237L, 239S, and 245L of NS4B are crucial for this regulation.

HCV NS4B has four transmembrane domains (TMDs) containing 70 amino acids (residues 192 to 261) within its carboxy terminus, which is called the NS4B carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) (44). The NS4B CTD is located on the cytosolic side of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, and most of the residues in this region are required for HCV genome replication, perhaps through an interaction with viral and host factors (2). Here, we evaluated the role of the NS4B CTD in the regulation of the STAT3 signaling cascade. To determine the sequences of NS4B protein required for the activation of STAT3, we generated 4 deletion mutants of the NS4B protein, named NS4BΔC1, NS4BCTD, NS4ΔC2, and NS4BΔC3 (Fig. 5A). The 4 mutated NS4B genes were then subcloned into the expression vector to yield four plasmids, pCMV-NS4BΔC1, pCMV-NS4BCTD, pCMV-NS4BΔC2, and pCMV-NS4BΔC3.

Fig 5.

Function of HCV NS4B CTD in the regulation of STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, ERK, and JNK. (A) Schematic diagram of the NS4B deletion mutants. The numbers indicate the amino acid residues located in the NS4B protein. (B to and D) Huh7 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing NS4B protein or its truncated mutant proteins. The relative levels of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 mRNA were measured at 48 h posttransfection using real-time PCR, and the levels of the p-STAT3, STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were determined by Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. The MMP-2 and Bcl-2 levels in each sample were normalized by dividing by the GAPDH quantity. (E) Sequences of amino acids 226 to 250 of wild-type NS4B and its mutants. Mutated amino acids are underlined. (F to and H) Huh7 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing NS4B protein or its mutants. The relative levels of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 mRNA were measured at 48 h posttransfection using real-time PCR, and the levels of the p-STAT3, STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were determined by Western blot analysis.

Huh7 cells were transfected with each of the plasmids, and the effects of these mutant NS4B proteins on the regulation of MMP-2, Bcl-2, STAT3, ERK, and JNK were evaluated. Real-time PCR analyses indicated that the relative levels of MMP-2 mRNA (Fig. 5B) and Bcl-2 mRNA (Fig. 5C) were activated by NS4B, NS4B CTD, and NS4BΔC3 but not by NS4BΔC1 or NS4BΔC2. These results suggest that NS4B CTD is sufficient for the activation of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 and that the 24 residues (amino acids 227 to 250) of the NS4B CTD are essential for the regulation of MMP-2 and Bcl-2. The results also showed that the p-STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, p-ERK, and p-JNK proteins were upregulated by NS4B, NS4B CTD, and NS4BΔC3 but not by NS4BΔC1 or NS4BΔC2 (Fig. 5D). However, the levels of the STAT3, ERK, JNK, and β-actin proteins were relatively unchanged in the presence of NS4B and its mutants (Fig. 5D). These results demonstrate that the NS4B CTD is sufficient for the activation of STAT3, ERK, and JNK and suggest that amino acids 227 to 250 of NS4B play a critical role in the regulation of the signaling components.

Based on the results presented above, we attempted to determine which of the 24 residues of NS4B protein are required for the activation of MMP-2, Bcl-2, STAT3, ERK, and JNK. A series of NS4B point mutations was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis, in which amino acids 228D, 237L, 239S, 241T, 245L, and 250H were replaced by 228A, 237E, 239W, 241A, 245D, and 250E, respectively (Fig. 5E). Huh7 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing NS4B and each of the mutants. Real-time PCR showed that MMP-2 mRNA (Fig. 5F) and Bcl-2 mRNA (Fig. 5G) were activated by NS4B, D228A, T241A, and H250E but not by L237E, S239W, and L245D. These results suggest that amino acids 237L, 239S, and 245L are essential for the activation of MMP-2 and Bcl-2 but that amino acids 228D, 241T, and 250H are not essential for such regulation. Western blot analyses indicated that the p-STAT3, MMP-2, Bcl-2, p-ERK, and p-JNK proteins were enhanced by NS4B, D228A, T241A, and H250E but not by L237E, S239W, or L245D (Fig. 5H). These results demonstrate that amino acids 237L, 239S, and 245L play critical roles in the regulation of STAT3, ERK, and JNK, while amino acids 228D, 241T, and 250H are not involved in this regulation.

DISCUSSION

HCV persistent infection is associated with a variety of human liver diseases, including HCC. However, the mechanisms by which HCV infection causes chronic liver diseases remain unclear. Here, we demonstrated that STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 are significantly stimulated in the PBMCs of patients with HCV infection and in cell cultures infected with HCV. These results are consistent with those of previous studies showing that MMP-2 and Bcl-2 levels are elevated in the serum of patients with HCC, cirrhosis, and chronic hepatitis (15, 23, 28, 63).

It has been reported that HCV is able to infect not only hepatocytes but also PBMCs (37, 54). Immediately after discovery of the virus in 1989, different groups showed that HCV replicates in lymphoid cells by infecting macrophages and B and T lymphocytes (8, 24, 58). Moreover, several reports described the presence of the replicative intermediate or negative strand in PBMCs (47, 48, 70). Our results show that both HCV plus-strand RNA and minus-strand RNA can be detected in the PBMCs of patients with HCV infection, and these findings are consistent with previous reports (6, 11, 27). The presence of the replicative form of HCV in PBMCs suggests that these cells can be a virus reservoir capable of reinfecting the liver in transplant patients or in subjects treated with IFN (56, 57). This lymphotropism may explain the association between this virus and certain lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) (51). It is likely that HCV infection of T and B lymphocytes is responsible, at least in part, for the many extrahepatic disorders often observed in individuals chronically infected with the virus (17, 18, 19).

Although the HCV core and NS5A proteins function as transcriptional transactivators for many cellular genes, such as NF-κB, AP-1, SRE, and STAT3 (10, 16, 32, 49), the molecular basis for hepatocellular MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression in patients with chronic HCV infection remains unknown. We revealed that HCV activates MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression by regulating the STAT3 signaling pathway. It has been reported that STAT3 induces MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression (5), and we demonstrate for the first time that STAT3 plays a role in the regulation of gene expression during HCV infection. Following phosphorylation, STAT3 is dimerized and translocated to the nucleus to activate downstream target genes (20, 40). We demonstrate that the HCV NS4B protein activates STAT3 by enhancing the phosphorylation and translocation of STAT3, thereby activating MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression.

STAT3 is involved in the transduction of cellular signals and the induction of gene expression in response to cytokine receptor stimulation (20, 40). The primary function of MMP-2 is to degrade proteins in the extracellular matrix. Physiologically, MMP-2 plays a role in normal tissue remodeling events such as embryonic development, reproduction, and tissue remodeling, as well as in disease processes, such as arthritis, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Bcl-2 is a proto-oncogene that suppresses apoptosis in a variety of cell systems, regulates cell death by controlling mitochondrial membrane permeability, and inhibits caspase activity either by preventing the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria or by binding to apoptosis-activating factor 1 (APAF-1).

The mechanism by which HCV regulates STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 was investigated in this study. We found that HCV NS4B activates the JNK and ERK signaling cascade, resulting in the activation of STAT3 activity and MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression. ERK and JNK have been implicated in relaying extracellular signals to the nucleus and in mediating proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and stress by regulating transcription factors (25, 33, 53). Thus, our results demonstrating that HCV activates STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 may reveal a novel mechanism underlying the pathogenesis and tumorigenesis caused by HCV infection.

STAT3 is thought to regulate the MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression mediated by a variety of stimulating agents (5, 7, 29, 35). In this study, we showed that the HCV NS4B protein regulates STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 in the human liver cell line Huh7. STAT3 is essential for NS4B-induced gene expression, because knockdown of STAT3 prevents NS4B from activating MMP-2 and Bcl-2. In addition, we demonstrated that NS4B activates MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression by stimulating STAT3 signaling and repressing the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS3) expression and that PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCε are involved in NS4B-mediated STAT3 activation. Members of the SOCS family are known to negatively regulate the activity of STAT3. Our results indicating that HCV NS4B stimulates STAT3 activity by inhibiting the activity of its repressor, SOCS3, suggest that the activation of STAT3 regulated by NS4B is through repression of SOCS3. PKC comprises a family of serine/threonine protein kinases that play important roles in cellular signal transduction cascades. Thus, in this study we demonstrated that multiple cellular signaling cascades are involved in the regulation of STAT3, MMP-2, and Bcl-2 in response to HCV infection.

NS4B is a poorly characterized hydrophobic protein that may play a role in the induction of cell transformation and tumorigenesis (14). Other activities associated with NS4B include modulation of NS5A hyperphosphorylation (30, 34), transactivation of interleukin 8 (IL-8) (31), and induction of unfolded protein response- and endoplasmic reticulum overload response-dependent NF-κB activation (39, 60, 68, 69). NS4B also interacts with other HCV nonstructural proteins and is involved in HCV RNA synthesis (1, 3, 13, 22). The NS4B CTD (44) interacts with the NS3 protein (50) and viral RNA (14), is involved in NS4B oligomerization (64), and plays a role in viral RNA replication (30). A recent report has shown that the NS4B CTD is partially responsible for the formation and function of the HCV replication complex (2). The cytosolic CTD plays an important role in HCV genome replication, perhaps by interacting with viral and host factors. Thus, NS4B plays a central role in HCV genome replication. In this study, we demonstrated that NS4B CTD is sufficient for the activation of STAT3, ERK, and JNK, thereby upregulating MMP-2 and Bcl-2. We also revealed that the last 24 amino acids (residues 227 to 250) of NS4B play a critical role in the regulation of STAT3, ERK, and JNK signaling pathways. Among the 24 amino acids, 3 residues (237L, 239S, and 245L) are essential for the function of NS4B in the regulation of these signaling pathways.

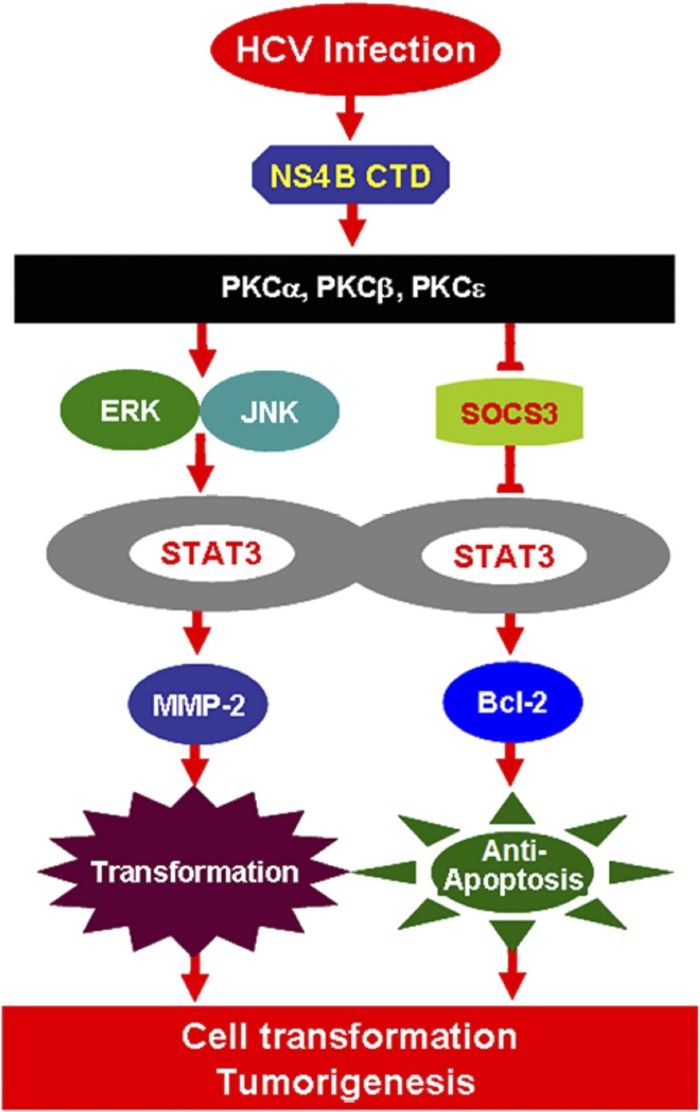

In conclusion, we have revealed a novel mechanism in which HCV infection activates STAT3 signaling through multiple cellular signaling pathways. During HCV infection, the viral protein NS4B activates the expression of several members of the PKC superfamily, stimulates the ERK/JNK signaling cascades, and represses SOCS3 expression, resulting in the activation of STAT3 activity by enhancing the phosphorylation and translocation of STAT3. Activated STAT3 then stimulates MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression, thereby resulting in the regulation of cell transformation, apoptosis, and possibly, tumorigenesis in response to HCV infection (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

A novel mechanism in which HCV infection activates STAT3 through multiple cellular signaling pathways. During HCV infection, the viral protein NS4B activates the expression of several members of the PKC family, stimulates the JNK/ERK signaling cascade, represses the SOCS3 expression, and enhances STAT3 activity, which in turn stimulates MMP-2 and Bcl-2 expression, resulting in the control of cell transformation, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis in response to HCV infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants from the Major State Basic Research Development Program (973 Program; 2012CB518900 and 2009CB522506), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81171525), the National Mega Project on Major Infectious Diseases Prevention (2012ZX10002006-003 and 2012ZX10004-207), the National Mega Project on Major Drug Development (2011ZX09401-302-1), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (1102001), the International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of China (2011DFA31030), and the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (20090141110033).

We thank Charles M. Rice of Rockefeller University for kindly providing the HCV plasmid pFL-J6/JFH5′C19Rluc2Aubi, Takaji Wakita of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases of Japan for providing HCV strain JFH-1, Francis Chisari of the Scripps Research Institute for providing the Huh7.5.1 cell line, Melanie Cobb of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for providing the ERK1 and ERK2 mutants, Michael Karin of the University of California at San Diego for providing JNK mutants, and Li Liu of Tsinghua University in China for providing the plasmid pGL3-APRE-luc.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ali N, Tardif KD, Siddiqui A. 2002. Cell-free replication of the hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon. J. Virol. 76:12001–12007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aligo J, Jia SAZ, Manna D, Konan KV. 2009. Formation and function of hepatitis C virus replication complexes require residues in the carboxy-terminal domain of NS4B protein. Virology 393:68–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alter MJ. 1997. Epidemiology of hepatitis C. Hepatology 26:62S–65S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bates SH, et al. 2003. STAT3 signalling is required for leptin regulation of energy balance but not reproduction. Nature 421:856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhattacharya S, Ray RM, Johnson LR. 2005. STAT3-mediated transcription of Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and c-IAP2 prevents apoptosis in polyamine-depleted cells. Biochem. J. 392:335–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bouffard P, Hayashi PH, Acevedo R, Levy N, Zeldis JB. 1992. Hepatitis C virus is detected in a monocyte/macrophage subpopulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infected patients. J. Infect. Dis. 166:1276–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Choi HJ, Lee JH, Park SY, Cho JH, Han JS. 2009. STAT3 is involved in phosphatidic acid-induced Bcl-2 expression in HeLa cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 41:94–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choo QL, et al. 1989. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 244:359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung J, Uchida E, Grammer TC, Blenis J. 1997. STAT3 serine phosphorylation by ERK-dependent and-independent pathways negatively modulates its tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6508–6516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chung YL, Sheu ML, Yen SH. 2003. Hepatitis C virus NS5A as a potential viral Bcl-2 homologue interacts with Bax and inhibits apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 107:65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crovatto M, et al. 2000. Peripheral blood neutrophils from hepatitis C virus-infected patients are replication sites of the virus. Haematologica 85:356–361 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Di Bisceglie AM. 1997. Hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 26:34S–38S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Egger D, et al. 2002. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins induces distinct membrane alterations including a candidate viral replication complex. J. Virol. 76:5974–5984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Einav S, et al. 2008. The nucleotide binding motif of hepatitis C virus NS4B can mediate cellular transformation and tumor formation without ha-ras co-transfection. Hepatology 47:827–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El-Gindy I, El Rahman A, El-Alim MA, Zaki S. 2003. Diagnostic potential of serum matrix metalloproteinase-2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 as non-invasive markers of hepatic fibrosis in patients with HCV related chronic liver disease. Egypt. J. Immunol. 10:27–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feng X, et al. 2011. Hepatitis C virus core protein promotes the migration and invasion of hepatocyte via activating transcription of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer. Virus Res. 158:146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferri C, La Civita L, Zignego AL, Pasero G. 1997. Hepatitis-C-virus infection and cancer. Int. J. Cancer 71:1113–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferri C, La Civita L, Zignego AL, Pasero G. 1997. Viruses and cancers: possible role of hepatitis C virus. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 27:711–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferri C, et al. 1995. Etiopathogenetic role of hepatitis C virus in mixed cryoglobulinemia, chronic liver diseases and lymphomas. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 13(Suppl. 13):S135–S140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giraud S, et al. 2002. Functional interaction of STAT3 transcription factor with the coactivator NcoA/SRC1a. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8004–8011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gong G, Waris G, Tanveer R, Siddiqui A. 2001. Human hepatitis C virus NS5A protein alters intracellular calcium levels, induces oxidative stress, and activates STAT-3 and NF-κB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:9599–9604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gosert R, et al. 2003. Identification of the hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex in Huh-7 cells harboring subgenomic replicons. J. Virol. 77:5487–5492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guo XZ, Shao XD, Liu MP. 2002. Effect of bax, bcl-2 and bcl-xL on regulating apoptosis in tissues of normal liver and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 8:1059–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hellings JA, van der Veen-du Prie J, Snelting-van Densen R, Stute R. 1985. Preliminary results of transmission experiments of non-A, non-B hepatitis by mononuclear leucocytes from a chronic patient. J. Virol. Methods 10:321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hill CS, Treisman R. 1995. Transcriptional regulation by extracellular signals: mechanisms and specificity. Cell 80:199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Houghton M, Weiner A, Han J, Kuo G, Choo QL. 1991. Molecular biology of the hepatitis C viruses: implications for diagnosis, development and control of viral disease. Hepatology 14:381–388 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsieh TT, Yao DS, Sheen IS, Liaw YF, Pao CC. 1992. Hepatitis C virus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 98:392–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iwata A, et al. 2011. Extracellular administration of Bcl2 protein reduces apoptosis and improves survival in a murine model of sepsis. PLoS One 6:e14729 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiang RQ, et al. 2011. Interleukin-22 promotes human hepatocellular carcinoma by activation of STAT3. Hepatology 54:900–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones DM, Patel AH, Targett-Adams P, McLauchlan J. 2009. The hepatitis C virus NS4B protein can trans-complement viral RNA replication and modulates production of infectious virus. J. Virol. 83:2163–2177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kadoya H, Nagano-Fujii M, Deng L, Nakazono N, Hotta H. 2005. Nonstructural proteins 4A and 4B of hepatitis C virus transactivate the interleukin 8 promoter. Microbiol. Immunol. 49:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kato N, et al. 2000. Activation of intracellular signaling by hepatitis B and C viruses: C-viral core is the most potent signal inducer. Hepatology 32:405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khokhlatchev AV, et al. 1998. Phosphorylation of the MAP kinase ERK2 promotes its homodimerization and nuclear translocation. Cell 93:605–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koch JO, Bartenschlager R. 1999. Modulation of hepatitis C virus NS5A hyperphosphorylation by nonstructural proteins NS3, NS4A, and NS4B. J. Virol. 73:7138–7146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kortylewski M, Jove R, Yu H. 2005. Targeting STAT3 affects melanoma on multiple fronts. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 24:315–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kuo G, et al. 1989. An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science 244:362–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lamelin JP, Zoulim F, Trepo C. 1995. Lymphotropism of hepatitis B and C viruses: an update and a newcomer. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Res. 25:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lauer GM, Walker BD. 2001. Hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li S, et al. 2009. Hepatitis C virus NS4B induces unfolded protein response and endoplasmic reticulum overload response-dependent NF-κB activation. Virology 391:257–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin Q, et al. 2005. Constitutive activation of JAK3/STAT3 in colon carcinoma tumors and cell lines: inhibition of JAK3/STAT3 signaling induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest of colon carcinoma cells. Am. J. Pathol. 167:969–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu M, et al. 2007. Spike protein of SARS-CoV stimulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression via both calcium-dependent and calcium-independent protein kinase C pathways. FASEB J. 21:1586–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu S, et al. 2012. Major vault protein: a virus-induced host factor against viral replication through the induction of type-I interferon. Hepatology 56:57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lu LL, et al. 2008. NS3 protein of hepatitis C virus regulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression through multiple signaling pathways. Virology 371:61–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lundin M, Monne M, Widell A, von Heijne G, Persson MAA. 2003. Topology of the membrane-associated hepatitis C virus protein NS4B. J. Virol. 77:5428–5438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mauro A, et al. 2002. PKCα-mediated ERK, JNK and p38 activation regulates the myogenic program in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. J. Cell Sci. 115:3587–3599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mellor H, Parker PJ. 1998. The extended protein kinase C superfamily. Biochem. J. 332(Pt 2):281–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Müller H, et al. 1994. B-lymphocytes are predominantly involved in viral propagation of hepatitis C virus (HCV). Arch. Virol. Suppl. 9:307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Muratori L, et al. 1994. Testing for hepatitis C virus sequences in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with chronic hepatitis C in the absence of serum hepatitis C virus RNA. Liver 14:124–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nunez O, et al. 2004. Increased intrahepatic cyclooxygenase 2, matrix metalloproteinase 2, and matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression is associated with progressive liver disease in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: role of viral core and NS5A proteins. Gut 53:1665–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Paredes AM, Blight KJ. 2008. A genetic interaction between hepatitis C virus NS4B and NS3 is important for RNA replication. J. Virol. 82:10671–10683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Peña LR, Nand S, De Maria N, Van Thiel DH. 2000. REVIEW: Hepatitis C virus infection and lymphoproliferative disorders. Dig. Dis. Sci. 45:1854–1860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Penin F, Dubuisson J, Rey FA, Moradpour D, Pawlotsky JM. 2004. Structural biology of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 39:5–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Price MA, Cruzalegui FH, Treisman R. 1996. The p38 and ERK MAP kinase pathways cooperate to activate ternary complex factors and c-fos transcription in response to UV light. EMBO J. 15:6552–6563 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Santini G, et al. 1995. HCV and lymphoproliferative diseases. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 13(Suppl 13):S51–S57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sarcar B, Ghosh AK, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. 2004. Hepatitis C virus NS5A mediated STAT3 activation requires co-operation of Jak1 kinase. Virology 322:51–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schmidt WN, et al. 1998. Effect of interferon therapy on hepatitis C virus RNA in whole blood, plasma, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Hepatology 28:1110–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schmidt WN, et al. 1997. Distribution of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in whole blood and blood cell fractions: plasma HCV RNA analysis underestimates circulating virus load. J. Infect. Dis. 176:20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shimizu YK, Iwamoto A, Hijikata M, Purcell RH, Yoshikura H. 1992. Evidence for in vitro replication of hepatitis C virus genome in a human T-cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:5477–5481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Simon AR, et al. 2000. Regulation of STAT3 by direct binding to the Rac1 GTPase. Science 290:144–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tong WY, et al. 2002. Physical interaction between hepatitis C virus NS4B protein and CREB-RP/ATF6 beta. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 299:366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Turkson J, et al. 1999. Requirement for Ras/Rac1-mediated p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling in Stat3 transcriptional activity induced by the Src oncoprotein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7519–7528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wheeler DL, Li Y, Verma AK. 2005. Protein kinase C epsilon signals ultraviolet light-induced cutaneous damage and development of squamous cell carcinoma possibly through induction of specific cytokines in a paracrine mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 81:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yang Y, et al. Clinical significance of Cox-2, Survivin and Bcl-2 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Med. Oncol. 28:796–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yu GY, Lee KJ, Gao L, Lai MMC. 2006. Palmitoylation and polymerization of hepatitis C virus NS4B protein. J. Virol. 80:6013–6023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yu L, Wang L, Chen S. 2012. Exogenous or endogenous Toll-like receptor ligands: which is the MVP in tumorigenesis? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69:935–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yu XW, Kennedy RH, Liu SJ. 2003. JAK2/STAT3, not ERK1/2 pathway mediates interleukin-6-elicited inducible NOS activation and decrease in contractility in adult ventricular myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16304–16309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhang Q, et al. 2012. Activation of the Ras/Raf/MEK pathway facilitates hepatitis C virus replication via attenuation of the interferon-JAK-STAT pathway. J. Virol. 86:1544–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zheng Y, et al. 2005. Hepatitis C virus non-structural protein NS4B can modulate an unfolded protein response. J. Microbiol. 43:529–536 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zheng Y, et al. 2005. Gene expression profiles of HeLa cells impacted by hepatitis C virus non-structural protein NS4B. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38:151–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zignego AL, et al. 1992. Infection of peripheral mononuclear blood cells by hepatitis C virus. J. Hepatol. 15:382–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]