Abstract

The Picornaviridae are a large family of small, spherical RNA viruses that includes numerous pathogens. The picornavirus structural proteins VP0, VP1, and VP3 are believed to first form protomers, which then form 14S particles and subsequently assemble to form empty and RNA-filled particles. 14S particles have long been presumed to be pentamers. However, the structure of the 14S particles, their mechanism of assembly, and the role of empty particles during infection are all unknown. We established an in vitro assembly system for bovine enterovirus (BEV) by using purified baculovirus-expressed proteins. By Rayleigh scattering, we determined that 14S particles are 488 kDa, confirming they are pentamers. Image reconstructions based on negative-stain electron microscopy showed that 14S particles have 5-fold symmetry, and their structures correlate extremely well with the corresponding pentamer from crystal structures of mature BEV. Purified 14S particles readily assemble in response to increasing ionic strength or temperature to form 5.8-MDa 12-pentamer particles, indistinguishable from native empty particles. Surprisingly, empty particles were sufficiently stable that, under physiological conditions, dissociation is unlikely to be a biologically relevant reaction. This suggests that empty particles are not a storage form of 14S particles, at least for bovine enterovirus, but are either a dead-end product or direct precursor into which viral RNA is packaged by as-yet-unidentified machinery.

INTRODUCTION

The Picornaviridae are an important family of human and animal pathogens, including poliovirus (PV), human rhinovirus (HRV), enterovirus 71, hepatitis A virus, and foot-and-mouth disease virus (31). They comprise one of the simplest architectures for a nonenveloped RNA virus, with a single-strand plus-sense RNA genome encapsidated in a spherical protein capsid. The 30-nm-diameter capsid is comprised of 60 copies of each of the structural proteins, VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4, arranged in a pseudo-T=3 (T=1) icosahedral lattice (31). A prominent feature of picornavirus infection is the coexistence of several kinds of subviral particles (8, 10, 37). In enteroviruses, the myristylated structural polypeptide P1 is cotranslationally cleaved by the viral protease 3CD, resulting in a heterotrimeric protomer (VP0-VP3-VP1) that sediments at 5S (27, 31). It is believed that 5S protomers self-associate to form 14S particles (VP0-VP3-VP1)5 and that 12 copies of 14S particles can self-assemble into an 80S empty capsid [(VP0-VP3-VP1)5]12 (32, 33). (The 80S sedimentation coefficient varies slightly for different picornaviruses under different conditions.) The mechanisms governing this self-assembly reaction and the roles for empty capsid, however, are poorly defined. The mechanisms of RNA recruitment and assembly of an RNA-filled particle are completely undefined. RNA-filled particles autoproteolytically mature to virions by cleavage of VP0 into VP2 and VP4. Due to their simplicity, picornaviruses could arguably become one of the best models for the study of virus assembly.

Relating assembly to biology requires an accurate description of the assembly path. However, a description of the assembly unit structure is lacking, and the path of assembly leading to an empty particle is poorly understood. The identities of components have been largely deduced from sedimentation velocity (30) or size exclusion chromatography (SEC) (15). Variations among different preparations have significantly complicated the interpretations of assembly reactions. For example, different kinds of 80S particles have been reported for PV (20). It is also not clear whether the 45S (34, 37) or 53S (15) particles are on-path intermediates from 14S to 80S particles. The structural basis for the assembly has also undergone limited investigation; only three empty capsid structures have been reported (1, 7, 41) (in contrast to over 100 mature picornavirus structures [22]), and there is no structure for the 14S particles except based on inference from capsid structures.

The poor characterization of the assembly has also led to debatable roles for 80S empty capsid. The reported ability of 80S empty capsid to dissociate into 14S particles in vitro (12, 20, 26) led to a proposal that empty capsid is a storage form of 14S particles and it is the 14S particles that are the direct precursors that associate with RNA to form the provirion, [(VP0-VP3-VP1)5]12 RNA (24). Alternatively, empty capsid may be an immature particle into which RNA is packaged, driven by unknown machinery that may be associated with the viral replication complex (19, 23). Another possibility is that empty capsid is just a dead-end product (40).

We chose to quantitatively examine assembly of bovine enterovirus (BEV), a member of the Enterovirus genus that is closely related to PV and HRV but for which infection lacks pathogenic consequences (39). In culture, BEV infections produce high concentrations of unassembled capsid proteins and empty capsids, suggesting it is particularly attractive for assembly studies (37). In addition, the BEV structure (35) will facilitate interpretation of structural and assembly studies. Using the BEV system, we provide definitive evidence to demonstrate that the 14S particles are pentamers, confirming and elaborating on previous results with other picornaviruses (8, 10, 12, 15, 20, 25, 27, 37). We demonstrate that relatively weak interpentamer interactions drive pentamer assembly to form 12-pentamer empty capsids in response to increasing ionic strength and temperature. The resulting empty capsids are so stable that they are unlikely to readily dissociate under physiological conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BEV virion and empty particle purification and antibody production.

Infection and growth of BEV LC-R4 in murine L-929 cells were performed as previously described (6). Briefly, L-929 cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and penicillin (100 units/ml). High-titer lysates of BEV were produced by infecting monolayers of confluent roller cultures (850 cm2; Corning) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 in the presence of 5 μg/ml of actinomycin D.

Purification of 160S and 80S particles was carried out using a protocol revised from a previous study (37). Briefly, BEV-infected, L-929 cells were harvested 48 h postinfection and lysed by freeze-thawing. The crude lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min and then precipitated with 10% polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000; Sigma) at 4°C for 2 h. The pellet was resuspended in RSB buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA; pH 7.4) and fractionated on a 15-to-45% continuous Nycodenz gradient in RSB buffer prepared using a Gradient Master apparatus (BioComp Instruments, Inc.). Gradients were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 4 h in an SW41 rotor (Beckman). The bands containing the virus and the empty particles were extracted and dialyzed against RSB buffer to remove the Nycodenz. The protein composition was evaluated by 12% urea-SDS-PAGE, for which the gels were prepared with 4 M urea. An aliquot of the purified virus was inactivated by exposure to UV light for 20 min for polyclonal antibody (pAb) generation (Cocalico Biologicals, Inc.).

Generation of transfer plasmids and recombinant baculoviruses.

Production of BEV capsid proteins in insect cells required coexpression of the P1 structural proteins and the 3CD protease (11). Following a similar strategy demonstrated for enterovirus 71 (5), transfer plasmids for generation of recombinant baculovirus were generated using pFastBac DUAL (Invitrogen), which contains two multiple-cloning sites. Gene fragments encoding P1 (nucleotides 819 to 3338; 2,520 bp) and 3CD (nucleotides 5412 to 7343; 1,932 bp; GenBank accession number DQ092769) (42) from the full-length cDNA, reverse transcribed from the purified RNA genome of BEV LC-R4, were amplified by PCR. The primers used for P1 gene amplification were the following: 5′-CGCGGTCGACAAATGGGAGCCCAAA and 5′-CGCGCGGCCGCCTAGTAACTGGTAGAACTGGC. The primers incorporated SalI and NotI restriction enzyme sites (underlined), respectively. The primers for 3CD gene amplification were 5′-CGCGGCTAGCATGGGTCCTCTTTTTG and 5′-CGCGCATGCTCAGAAAGAGTCG, with added NheI and SphI restriction enzyme sites (underlined), respectively. The P1 gene fragment was cloned under the polyhedrin promoter, and the 3CD gene fragment was cloned under the p10 promoter. The resultant plasmid carrying two gene cassettes was designated pDual-P1-3CD. Recombinant baculoviruses were subsequently generated using the Bac-to-Bac system (Invitrogen). In brief, the recombinant plasmids were transformed into DH10Bac Escherichia coli (Invitrogen), in which the entire expression cassettes between Tn7L and Tn7R were transferred from pDual-P1-3CD to the bacmid by site-specific transposition. The subsequent bacmid isolation, transfection, and selection of the recombinant viruses were performed as per the manufacturer's instructions. Clones were screened and verified by PCR sequencing.

Expression and purification of capsid proteins.

BEV capsid proteins were produced by infecting Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cells cultured in SF-900 III medium (Invitrogen) at 27°C with the recombinant baculoviruses at an MOI of 2. Cultures initiated at 1 × 106 cells/ml were grown to 4 × 106 cells/ml and then infected with recombinant baculovirus at an MOI of 2. At 48 h postinfection, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer PS (20 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl; pH 6) at 4°C. Cells were lysed by sonication, and the lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min to pellet cell debris. Supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min to remove baculovirus. The supernatant was then loaded onto a Mono Q column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer PS; samples were eluted by a step gradient of 50 mM, 150 mM, and 500 mM NaCl in PS. Fractions containing capsid proteins were concentrated and further purified on a 22-ml Superose 6 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in PS. Protein purity was assessed at each step by urea-SDS-PAGE using 12% acrylamide gels. The identity of the capsid proteins was confirmed with Western blot assays using our anti-BEV polyclonal antibodies as probes. The protein concentration was determined from the UV absorbance, using an extinction coefficient (ε280) of 140,650 M−1 cm−1 per VP0-VP1-VP3 protomer.

Transmission electron microscopy and image reconstruction.

Specimens were prepared by applying the protein solutions on glow-discharged carbon-coated copper grids (EMS), washed with deionized water, negative stained with 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate (UA), and blotted to dry. The images were acquired at ×40,000 magnification using a JEM-1010 transmission electron microscope (TEM; JEOL Ltd., Japan) operated at 80 kV and equipped with a Gatan Orius charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera (Gatan, Inc.). For image analysis and three-dimensional (3-D) reconstructions, specimens were prepared following the same protocols described above. Images were collected using a JEOL JEM-3200FS TEM operated at 300 kV under low-dose conditions (≤14 e−/Å2) at a nominal magnification of ×60,000 on a Gatan UltraScan 4000 4k by 4k CCD camera (equivalent to 1.8 Å per pixel at the specimen space). Digitized micrographs with minimum astigmatism, specimen drift, and charging were used for the subsequent image processing. Reference-free classification, initial model building, orientation determination, and 3-D reconstructions were carried out by using the EMAN (version 1.9) and EMAN2 software packages (38). After 16 rounds of refinement at an angular spacing of 5°, the final reconstruction was generated from 3,915 particles. The resolution was estimated to be 30 Å, based on a Fourier shell correlation cutoff of 0.5. Thus, the final reconstruction was low pass filtered to 30 Å for visualization purposes. The atomic coordinates for the BEV capsid (35) were obtained from VIPERdb (3). The pentamer coordinates were extracted and docked into an EM density map by using UCSF's Chimera program (28).

SEC and multiangle laser light scattering (SEC-MALLS).

SEC was performed using a 22-ml Superose 6 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer PS (20 mM phosphate, 50 mM NaCl; pH 6). The column was mounted on a Shimadzu high-performance liquid chromatograph equipped with a thermostatted autoinjection module. Assembly was induced by mixing capsid proteins with an equal volume of buffer PS with 0.8 M NaCl and incubated for 24 h at 25°C. Peaks at 280 nm were quantified after manual baseline correction with the supplied LCSolutionssoftware (Shimadzu). To test the effect of pH, buffers at pH 6, 6.5, and 7.4 were prepared using 20 mM phosphate; buffers at pH 8, 8.4, and 9 were prepared using 20 mM Tris-HCl. Samples of 0.3 μM purified pentamer were incubated in the appropriate buffer with 150 mM NaCl at 37°C for 10 min and analyzed by SEC in a Superose 6 column equilibrated in the corresponding buffer.

SEC-MALLS was performed using a Superose 6 column in line with a Helios 17 angle MALLS detector and an Optilab REX refractometer (Wyatt Technology). Debye analysis of the data was performed using the program ASTRA (Wyatt Technology), assuming a refractive index increment of 0.185 for protein.

Light scattering.

Capsid assembly kinetics were determined based on light scattering (LS) as previously described (45). Briefly, capsid proteins were buffer exchanged to no-salt buffer PS (20 mM phosphate, pH 6) and preincubated at the desired temperature. Samples were mixed in a black-masked microcuvette with a path length of 0.3 cm (Hellma). Scattering was observed with a PTI fluorimeter, with both excitation and emission monochromators set to 330 nm. For each measurement, the base signal of 60 μl of 0.2 μM capsid protein was recorded for 50 s before an equal volume of PS with 0.8 M NaCl was added to induce assembly, and scattering was recorded for 500 s. The LS signals are reported in arbitrary units.

Calculations.

Data obtained by SEC were analyzed to determine ΔG as previously described (4). The reaction for BEV capsid assembly can be represented as an equilibrium described by the law of mass action:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Given the protein subunit geometry and the degeneracy of association based on capsid geometry, Kcapsid can be related to the association constant per pentamer-pentamer contact, or Kcontact (4, 43):

| (3) |

| (4) |

where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature kelvin. Kcapsid can also be related to the experimentally accessible pseudocritical concentration or the apparent dissociation constant, KD(apparent), where there are equal concentrations of reactant and product (14):

| (5) |

RESULTS

Expression of homogenous immature BEV capsid protein.

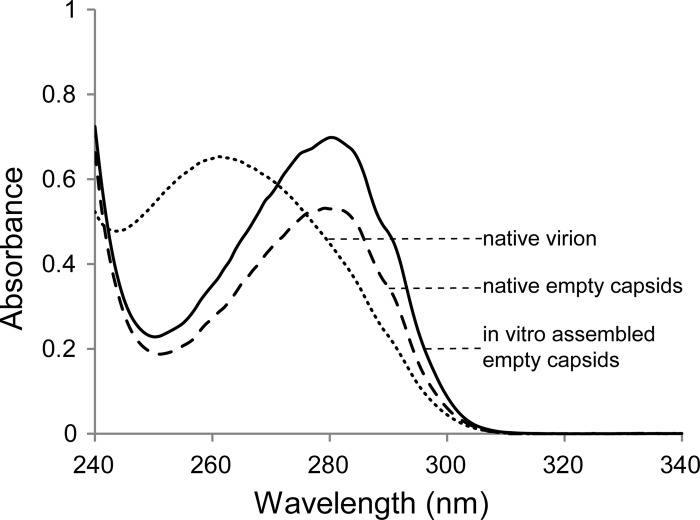

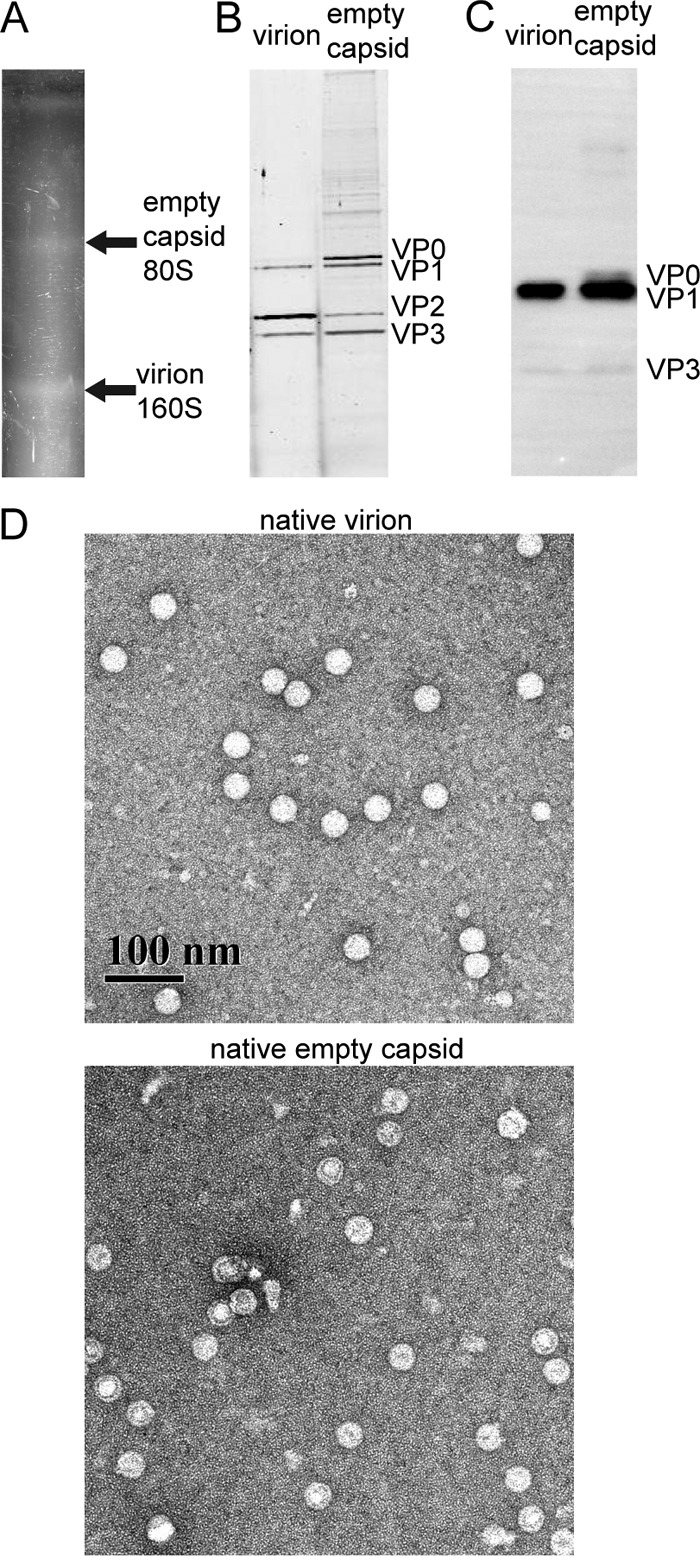

To characterize the native particles from BEV-infected murine L-929 cells and produce pAb against BEV, virion and empty capsid were purified by Nycodenz gradient ultracentrifugation (Fig. 1A). The gradient profile was consistent with previous sucrose gradient results (37), with estimated sedimentation values of 80S and 160S for empty capsid and virion bands, respectively. Absorbance measurements of the empty capsid and virion fractions indicated that the former had no detectable nucleic acid, whereas the latter contained RNA (Fig. 2). SDS-PAGE of the virion fraction showed that the vast majority of VP0 had been processed to VP2 (VP4 was not visible on these gels) (Fig. 1B). Only a small amount of VP0 was left intact (1, 37). By negative-stain TEM, virions were shown to be uranyl acetate impermeable (Fig. 1D).

Fig 1.

Characterization of BEV virion and 80S empty capsid from infected murine L-929 cells. (A) Photograph of a Nycodenz gradient, showing fractions assigned as 80S empty capsid and 160S virion. (B) Coomassie-stained urea-SDS-PAGE gel (prepared with 4 M urea) of purified virion and empty capsid. In the virion fraction, VP1, VP2, VP3, and a small amount of VP0 were evident (VP4 was not visible on this gel). The empty capsid fraction was dominated by VP0, VP1, and VP3; the VP2 band suggested the presence of some empty mature capsid. (C) Western blot of a urea-SDS-PAGE gel of virion and empty capsid fractions detected by anti-BEV pAb (1:10,000 dilution). The pAb recognizes VP0, VP1, and VP3. (D) TEM image of 2% uranyl acetate-stained virion and empty capsid. Magnification, ×40,000. Both the virion and empty capsid had spherical morphologies with a diameter of ca. 30 nm. Noticeably, the virion was resistant to stain, while most empty capsid particles were stain permeable. Some stain-resistant empty capsids were also observed.

Fig 2.

UV-Vis spectra of BEV native virions, native empty capsids, and in vitro-assembled empty capsids. Only native virions had prominent absorbance at 260 nm, while native empty capsids and in vitro-assembled empty capsids had characteristic protein spectra with maximum absorbance at 280 nm. The spectra were corrected for light scattering and baseline offset according to the methods of Porterfield et al. (29).

Although the empty capsid fraction appeared to be RNA free, based on the absorbance spectra (Fig. 2), the proteins in the empty capsid fraction appeared to be heterogeneous. A readily visible band on the SDS-PAGE gel indicated that substantial VP2 was present in the empty capsid fraction, as well as the expected VP0 (Fig. 1B). TEM showed that while most capsids were uranyl acetate permeable, a fraction was not (Fig. 1D). Western blot assays using pAb raised against mature virions showed recognition primarily of VP1 in both the empty capsid and virion fractions (Fig. 1C). Thus, both the empty capsid and virion fractions are complexes of the P1 proteins. However, based on processing of VP0 as observed by SDS-PAGE, our data suggested that some of the particles in the empty capsid fraction were virions that had actually undergone maturation cleavage but had lost their RNA genomes (possibly during purification). These heterogeneous particles were not suitable material for rigorous assembly studies.

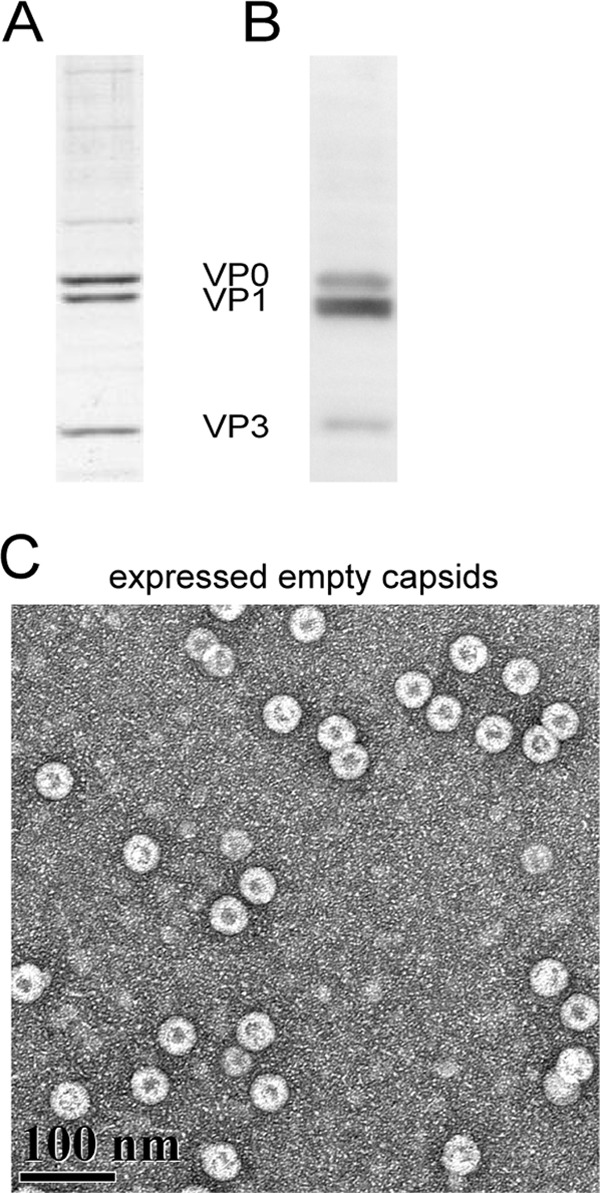

To obtain sufficient quantities of homogeneous BEV capsid proteins, a baculovirus expression system was established (5). Coexpression of the P1 structural protein and the 3CD protease by using recombinant baculovirus in insect cells led to overexpression of the P1 cleavage products VP0, VP1, and VP3, as shown by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A and B). These could be purified in the form of empty capsid-like particles, all of which were stain permeable (Fig. 3C). Absorbance spectra indicated that no detectable RNA copurified with these empty capsids (Fig. 2). There was no evidence of cleavage of VP0 to VP2 and VP4, confirming the homogeneous composition of immature capsid proteins.

Fig 3.

Production of BEV capsid proteins by using baculovirus expression. Capsid proteins purified from baculovirus expression system-infected Sf9 cells were characterized by a Coomassie blue-stained urea-SDS-PAGE gel (A), a Western blot (B), and a TEM image (2% uranyl acetate staining; magnification, ×40,000) (C). The Western blot was probed with anti-BEV pAb. VP0, VP1, and VP3 are evident in both panels A and B. No processed VP0 (i.e., VP2) was observed. In the micrographs (panel C), the VP0-VP1-VP3 complex was shown to be self-assembled into spherical virus-like particles, resembling authentic empty capsid. All particles were stain permeable.

BEV empty capsid assembles from 12 pentamers into a dodecahedron.

To provide a detailed description of BEV assembly, it was first necessary to define the basic unit and product of assembly. Serendipitously, we observed that purified 80S empty capsids, when incubated in low-ionic-strength buffer at 4°C, dissociated into a smaller complex that resembled 14S particles, as described in previous picornavirus assembly studies (31, 37). Furthermore, we observed that these 14S particles reassociated at higher ionic strengths and temperatures.

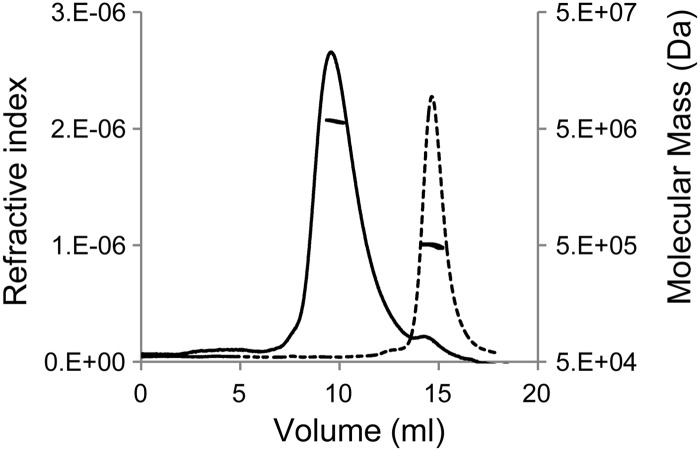

To determine the identity of the assembly unit and product, these 14S particles and in vitro-assembled products were subjected to SEC-MALLS. This technique measures the weight-average molecular weight (Mw) based on scattering extrapolated to a 0° angle and the diameter of the solute based on the angular dependence of scattering. The 14S particles eluted as a single symmetrical peak at 14.3 ml on a 22-ml Superose 6 column equilibrated with PS buffer (20 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl; pH 6), suggesting homogeneity (Fig. 4). In vitro-assembled product also showed a symmetrical peak that eluted at 9.4 ml, with a small peak that eluted at 14.3 ml (Fig. 4). The reduction of the height of the peak at 14.3 ml and appearance of the symmetrical peak at 9.4 ml suggest a direct transition from the 14S particles to a uniform-sized product. The mass of the 14S particle was determined to be 488 ± 10 kDa (mean ± standard deviation), within 5% of the calculated mass of 462 kDa for a pentameric complex of VP0, VP1, and VP3. The mass (from the Mw) of the assembled product was determined to be 5.79 ± 0.11 MDa, within 4% of the calculated mass of 5.57 MDa for a capsid of 12 pentamers. The radii of gyration of the 14S particles and 80S capsids in solution were 8.2 ± 1.2 nm and 13.2 ± 0.6 nm, respectively. These values were near the lower limit that can be measured with the 658-nm light source of our MALLS instrument, yet they were consistent with radii of putative pentamer and empty capsid as measured by TEM and also calculated values (7.8 nm for pentamer and 15.5 nm for virion) from the crystal structure of BEV (PDB accession code 1BEV) (35).

Fig 4.

SEC-MALLS of purified capsid subunits (dashed line) and in vitro-assembled capsids (solid line). The symmetries of the peaks suggested homogenous samples. The weight-average molecular mass data points, calculated at closely spaced intervals, formed a nearly horizontal line in the corresponding peaks. For assembled capsid, the mass was 5.79 ± 0.11 MDa, which is consistent with the molecular mass of a capsid of 12 pentamers. The small, late-eluting peak in the capsid chromatograph indicates a small amount of subunit in the sample. The mass of the subunits was 488 ± 10 kDa, which is within 5% of the 462-kDa molecular mass expected for a pentameric complex of capsid proteins VP0, VP1, and VP3.

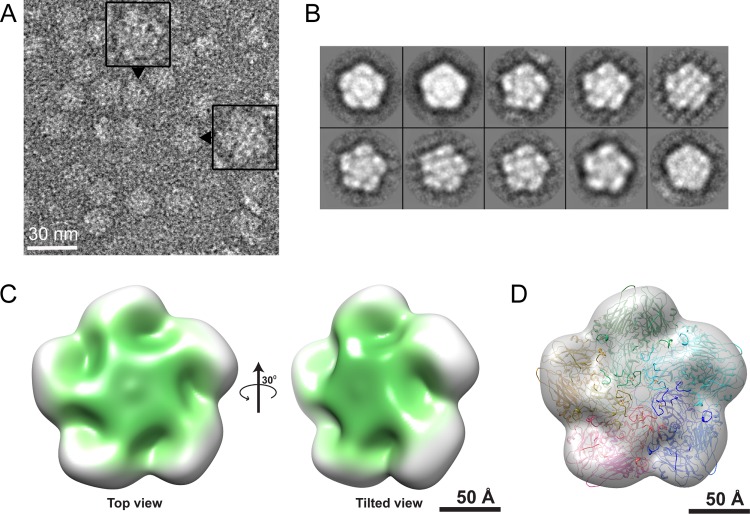

There are many ways to arrange 15 proteins to obtain a mass of 488 kDa. To define the geometry of the assembly unit, we determined the structure of the 14S particles under low-salt conditions by TEM and image reconstruction. Electron micrographs of negative-stained 14S particles revealed a consistent regular pentagonal morphology (Fig. 5A). Most of these 14S particles had diameters of about 16 nm, consistent with the MALLS measurement. Without imposing any symmetry constraints, the 2-D class averages of the particles displayed a distinct 5-fold symmetry (Fig. 5B). A 3-D model based on the negative-stain images, generated to 30-Å resolution, also indicated a 5-fold symmetric pentamer (Fig. 5C). Negative-stain EM reconstruction only showed the external envelope of the pentamer. Nonetheless, the pentamer density clearly showed features seen in the mature virus, including a “canyon” surrounding a putative VP1 plateau centered on the 5-fold symmetry axis. A model pentamer, derived from 1BEV, fit the density map with remarkable fidelity (Fig. 5D).

Fig 5.

Image reconstructions of 14S particles. (A) Electron micrograph of negatively stained 14S particles. Most particles had a diameter of about 16 nm, suggesting they lay flat upon the carbon-coated grid. Selected examples of apparent 5-fold symmetry were magnified (insets). (B) Reference-free 2-D class averages clearly showed a central density surrounded by five masses, further indicating the 5-fold symmetry evident in the raw data. (C) Top view (left) and tilted view (right) of the 3-D reconstruction of a BEV pentamer. (D) Transparent isosurface rendering of the top view in panel C, with the pentameric BEV capsid coordinates (PDB accession code 1BEV) fit into the reconstruction, revealing good agreement between the atomic coordinates and EM density map.

Empty capsid assembly is reversible, depending on solution conditions.

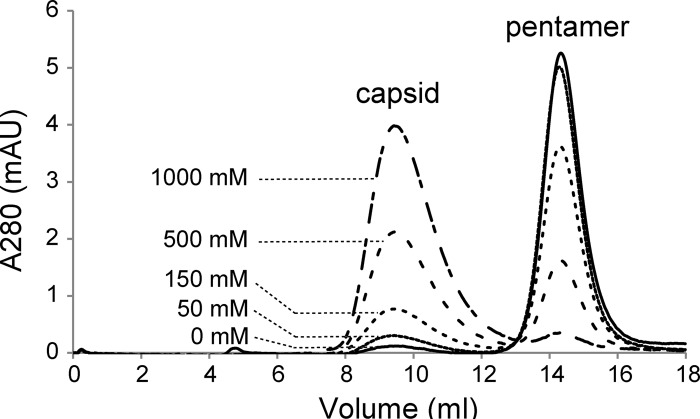

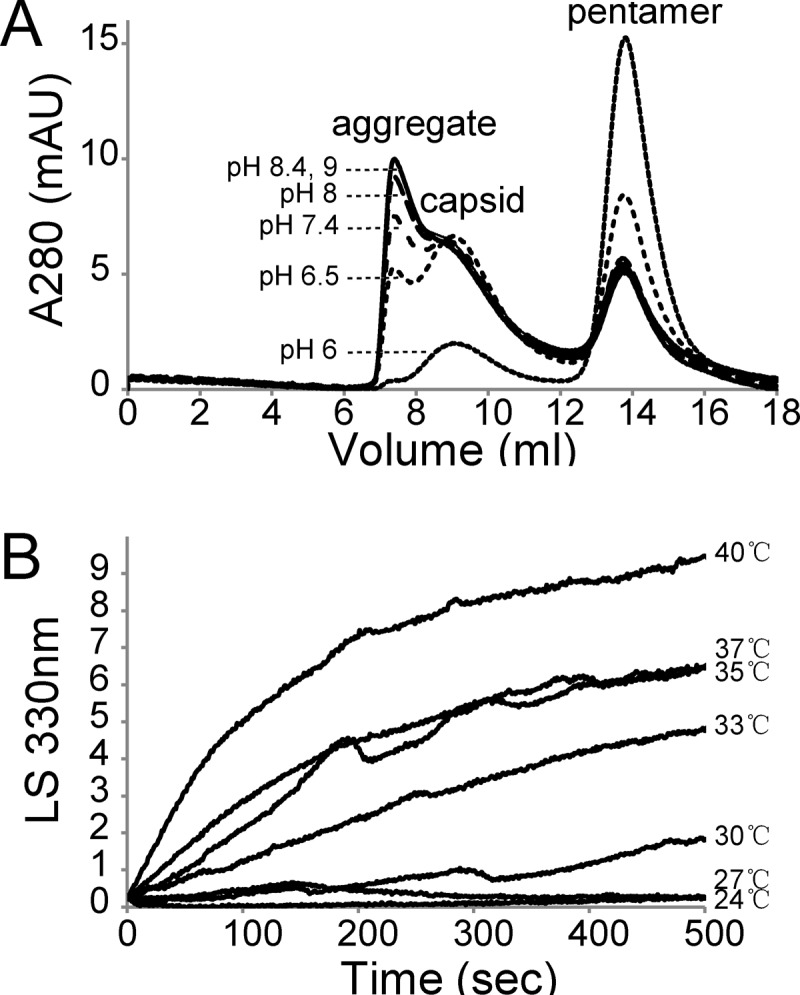

To quantitatively describe in vitro assembly, we tested conditions for their influence on the assembly reaction and the reversibility of assembly. First, pH was tested for its effect on assembly. Initially, the capsid proteins from insect cells were purified at 4°C using RSB buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) at pH 7.4. Surprisingly, however, there was a significant amount of aggregation in assembly reaction mixtures at pH 7.4 buffer after 10 min of incubation at 37°C, as shown by the amount of protein that eluted in the void volume (about 7.2 ml) preceding the capsid peak (about 9.4 ml) on the Superose 6 column (Fig. 6A). A series of pH levels were tested. A stronger association (demonstrated by lower concentrations of pentamers) and aggregation were observed at higher pHs. Minimal aggregation for in vitro capsid assembly was observed at pH 6 (Fig. 6A), which was used for subsequent assembly reactions.

Fig 6.

In vitro capsid assembly as a function of pH (A) and temperature (B). (A) Size exclusion chromatographs of capsid assembly reactions performed at pHs between 6 and 9. All samples had 0.3 μM purified pentamer in 150 mM NaCl buffered with 20 mM phosphate or Tris-HCl. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 10 min before injection onto a 22-ml SEC column equilibrated with the corresponding assembly buffer. Chromatographic traces for pH 8.4 and pH 9 largely overlapped and could not be discerned in the presence of other overlapping chromatographs, especially at the magnification used. (B) The temperature dependence of assembly was measured by LS at 330 nm. Pentamer at 0.2 μM in buffer PS without NaCl was preincubated at the desired temperature. Assembly was induced by mixing with an equal volume of buffer PS with buffered NaCl to a final concentration of 0.4 M NaCl.

To gain a feeling for the time course of assembly and to investigate the effect of temperature, we monitored the assembly kinetics by 90° light scattering (LS). LS, measured 90° from incident, is extremely sensitive to the weight-average molecular weight of the solute. For these studies, pentamers in low-salt buffer at pH 6 were preincubated at the indicated temperatures. Assembly was initiated by increasing the NaCl concentration. As shown in Fig. 6B, there was no visible assembly at or below 24°C within the experimental time frame. As the temperature was increased from 27°C to 40°C, both the rate of change and the overall LS signal increased. The higher LS signal indicated that more assembly was occurring. The temperature dependence of the amount of assembled capsid suggested that the assembly reaction is entropy driven; this result is also consistent with the stability of pentamers at 4°C.

Using PS buffer (20 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl) at pH 6, the assembly reaction was shown to be reversible as a function of ionic strength and temperature. Purified capsid proteins were prepared in buffer PS with 150 mM NaCl, allowed to assemble at 37°C for 10 min, and then transferred to PS with final NaCl concentrations of 0, 50, 150, 500, and 1,000 mM. To allow the maximal range in reassembly conditions, reaction mixtures with 0 or 50 mM NaCl were incubated at 4°C; reaction mixtures at 150, 500, and 1,000 mM NaCl were kept at 37°C. All reassembly reactions were evaluated by SEC. In 150 mM NaCl, the assembly reaction was shown to result in a mixture of about 25% capsid and 75% pentamer (Fig. 7). When this mixture was transferred to higher NaCl concentrations, the fraction of capsid increased; with lower NaCl concentrations, the fraction of pentamer increased, indicating a reversible assembly reaction. In 1 M NaCl, nearly 95% of the protein was in capsid form, but these capsids didn't dissociate when the ionic strength was reduced. We suggest that this irreversible high-salt assembly is analogous to the native-to-heated (N → H) conformational transitions observed for poliovirus 80S particles subjected to high-ionic-strength CsCl gradient purification (25).

Fig 7.

SEC overlays of capsid assembly as a function of ionic strength. Samples of 0.3 μM pentamer were preassembled in buffer PS (20 mM phosphate; pH 6) with 150 mM NaCl and transferred to PS with the indicated final NaCl concentration (0, 50, 150, 500, or 1,000 mM). Samples assembled in 150 mM and 500 mM NaCl could assemble and dissociate in response to changes in ionic strength and temperature. Samples were evaluated by SEC, using a Superose 6 column equilibrated with the corresponding buffer. Samples assembled in 1,000 mM NaCl would not dissociate, suggesting an irreversible conformational change.

Thermodynamic analysis revealed that empty capsid assembly is driven by weak protein-protein interactions.

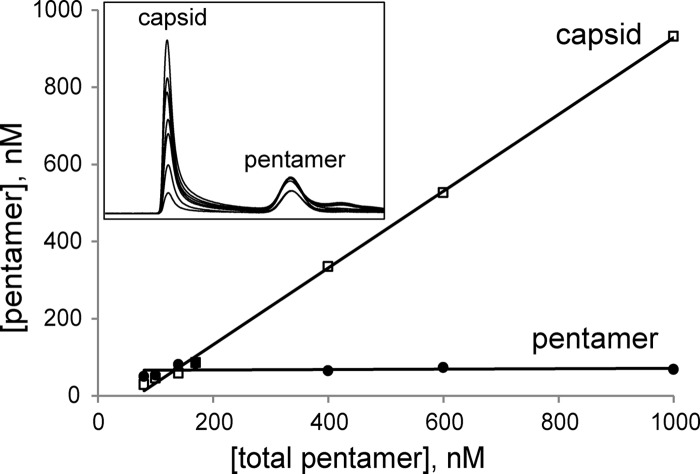

To determine capsid association energy, it was necessary to demonstrate that assembly is reversible (e.g., Fig. 7) and can reach equilibrium. A characteristic of a capsid assembly reaction at equilibrium is that a pseudocritical concentration [KD(apparent)] is seen in plots of the concentration of capsid or free subunit as a function of total subunit concentration (9, 44). Assembly reaction mixtures of various protein concentrations were incubated in 0.4 M NaCl at 25°C for 24 h. These conditions resulted in capsid yields similar to those at 150 mM NaCl and 37°C. The capsid and pentamer were then separated and quantified by SEC. The inset in Fig. 8 shows typical chromatographic overlays for empty capsid assembly reactions, with capsid eluting at 9.4 ml and pentamer at 14.3 ml. When the concentration of protein, in terms of the pentamer concentration, in capsid and free pentamer fractions was plotted as a function of the total pentamer concentration, a pseudocritical concentration, a horizontal line, for free pentamer was observed, with a y intercept of approximately 60 nM; this agreed with the x intercept of the trend line for capsid (Fig. 8).

Fig 8.

Determination of the pairwise association energy for capsid assembly. Pentamers were incubated with 0.4 M NaCl at 25°C for 24 h, followed by SEC quantification (inset). The pseudocritical concentration was estimated to be 60 nM, based on the free pentamer concentration (y intercept; solid circles) and the minimal pentamer concentration required for assembly of capsid (capsid x intercept; open squares). From these data and a knowledge of capsid geometry, the pairwise pentamer-pentamer association energy was determined to be −3.9 kcal/mol (44).

To determine the pairwise association energy, we applied a theoretical model developed previously (44) that has been successfully used for hepatitis B virus, Cowpea chlorotic mottle virus, and human papillomavirus assembly studies (4, 13, 21). From the equilibrated reaction, the association constant Kcapsid was obtained by the law of mass action and partitioned into Kcontact, the pairwise association constant between pentamers (equations 1 to 4). These two constants are directly related to the experimentally observable KD(apparent) for empty capsid assembly of 60 nM (equation 5). The pairwise association energy for pentamer-pentamer interactions was −3.9 kcal/mol (see Materials and Methods for equations). This pairwise energy corresponds to a dissociation constant of 1.4 mM. The much lower value of 60 nM for BEV's pseudocritical concentration arises from the fact that subunits are pentavalent. Capsids assemble with this remarkably weak dissociation constant because each pentamer makes five contacts with neighboring subunits. The weak association allows error correction and minimizes kinetic trapping (demonstrated at higher pH values) (43).

DISCUSSION

In vitro assembly experiments allow quantitative observation and analysis of complex reactions. For in vitro experiments, we developed a recombinant baculovirus expression system (5) that provided homogeneous self-assembling proteins that were indistinguishable from native particles (Fig. 1 and 3). The ability of pentamers to spontaneously assemble into empty capsids in a simple buffer system showed that assembly-promoting factors were not necessary to form empty capsid from 14S pentamers in vitro and, therefore, such factors may be unnecessary in vivo.

To allow a detailed analysis of assembly reactions, we first defined assembly reactants and products. Based on sedimentation values, it is generally accepted that 14S particles are pentamers and empty capsids are thus composed of 12 14S particles (8, 31). Roles for smaller components (e.g., 5S particles or individual proteins) in assembly reactions had not been ruled out, nor had the 5-fold symmetry of 14S been determined. By applying the sensitive and accurate mass measurement method provided by SEC-MALLS to purified reaction components, we unambiguously showed that pentamers are the basic assembly units and empty capsids are assembled from 12 pentamers (Fig. 4). These results were consistent with the size and pentagonal shape of 14S particles as determined by negative-stain image reconstruction (described below). To our knowledge, this is the first time definitive measurements have identified 14S as a pentagonal pentamer.

To further understand the structural basis of assembly, we examined the pentamer by using negative-stain TEM, and we obtained a 3-D model at 30-Å resolution (Fig. 5). The 2-D class averages of particles, with no symmetry imposed, revealed a distinct 5-fold symmetry (Fig. 5B). A pentameric molecular model derived from the crystal structure of BEV (PDB accession code 1BEV) (35) was fit to the 30-Å-resolution density map. Although the protein compositions were different between immature (VP0-VP1-VP3) and mature (VP1-VP2-VP3-VP4) capsid forms, the “mature” molecular model fit remarkably well to the density envelope (Fig. 5D). Also, despite possible staining artifacts, the low-density region observed surrounding the putative VP1 plateau resembled features known as the “canyon” seen in mature BEV (Fig. 5C) (36). Altogether, our findings suggest that the pentamer maintains its overall shape during assembly to empty capsids. The necessary structural rearrangements during assembly would mostly occur at the pentamer-pentamer interface. However, the density near the canyon was diffuse, suggesting there may be some additional molecular motion in this region (Fig. 5D).

To characterize empty capsid assembly in vitro, we explored conditions under which pentamers could assemble to complete empty capsid in the absence of defective assembly or aggregation. With limited knowledge of solution conditions for in vitro assembly of BEV empty capsid, we started the trial at the physiological pH, 7.4, as used in native virus particle preparation. Surprisingly, assembly at pH 7.4 produced aggregates larger than empty capsid, as shown by their SEC elution in the void volume, substantially preceding the capsid peak (Fig. 6A). Unlike with PV, where alkaline treatment dissociates empty capsid to 14S particles (20), alkaline pH induced more assembly and produced more aggregates, while slightly acidic pH and low ionic strength dissociated aggregates and/or empty capsid to pentamers; minimal aggregation was observed at pH 6 (Fig. 6A). In vitro aggregation may result from the concentrations of pentamer used in our studies, necessary to experimentally observe assembly. A possible explanation for the in vitro assembly working so well at pH 6 compared to physiological pH 7.4 might be that the charge states of a symmetry-related pair of histidine residues (VP2.H109, using the numbering scheme for 1BEV) located at the pentamer-pentamer interface. A repulsive charge at lower pH may weaken the association and hence attenuate aggregation and kinetic trapping. The temperature dependence of empty capsid assembly suggested that the reaction was entropy driven. This result is consistent with the hydrophobic surface shown buried at the pentamer-pentamer interface in the BEV crystal structure (35).

Empty capsid assembly was shown to be reversible as a function of ionic strength within a broad NaCl concentration range. However, high ionic strength, 1 M NaCl, rendered empty capsid nondissociable, even when transferred to low-ionic-strength buffer; this effect is analogous to the native-to-heated (N → H) transitions observed for PV 80S particles purified by using a high-ionic-strength CsCl gradient (25). The mechanism by which ionic strength drives reversible and irreversible in vitro assembly was not investigated in this study; we note that increasing ionic strength progressively stabilizes hydrophobic interactions.

We determined the association energy per pentamer-pentamer interaction as −3.9 kcal/mol, which corresponds to a very weak 1.4 mM dissociation constant. However, as each pentamer is pentavalent, the apparent dissociation constant for capsids is 60 nM (Fig. 8). With 30 contacts being made during assembly, this yields a stable empty capsid with a global energy of −117 kcal/mol. The weak interactions at the pentamer-pentamer interface may explain the “breathing” observed in mature PV (18) and mature HRV (17). It may also correlate with the rupture of a pentamer-pentamer interface to release poliovirus RNA (2, 16). The strong association energy (and the correspondingly low [KD(apparent)] of empty capsids suggests that they are unlikely to fall apart in vivo. Therefore, we suggest that 80S empty capsids are not a storage form of 14S pentamers, at least in BEV; they are either dead-end particles or are direct virion precursors into which RNA is packaged. However, this suggestion assumes that our experimental conditions accurately reflect capsid stability in a cell; thus, our proposal requires further in vivo testing.

This study has experimentally confirmed the identity of 14S particles as 5-fold symmetric pentamers and 80S empty particles as dodecahedra of pentamers, and it has also demonstrated that weak interactions drive BEV capsid assembly. This assembly mechanism may be useful as a general model for the assembly of all picornaviruses. Moreover, as one of the simplest cases of capsid assembly, with only 12 subunits, it serves as a powerful experimental system to refine mathematical descriptions of this complex reaction (44). One final point is that, although by convention picornaviruses (and most other spherical viruses) are described as icosahedral, an icosahedron of 20 triangles and a dodecahedron of 12 pentagons have the same 5-3-2 symmetry, and both are composed of 60 asymmetric units related by the same symmetry matrices (3). Here we have demonstrated that BEV follows a dodecahedral assembly mechanism and thus, from the perspective of assembly, we suggest that BEV and other Picornaviridae be considered dodecahedral viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Nickens and Suchetana Mukhopadhyay for advice and guidance with cell culture and protein expression. Electron microscopy was performed at the Indiana Molecular Biology Institute (Barry Stein) and the IU cryo-EM facility (David Morgan), which is part of the IU Nanoscale Characterization Center.

We acknowledge NIH grant AI077688 to A.Z.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Basavappa R, et al. 1994. Role and mechanism of the maturation cleavage of VP0 in poliovirus assembly: structure of the empty capsid assembly intermediate at 2.9 Å resolution. Protein Sci. 3:1651–1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bostina M, Levy H, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2011. Poliovirus RNA is released from the capsid near a twofold symmetry axis. J. Virol. 85:776–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carrillo-Tripp M, et al. 2009. VIPERdb2: an enhanced and web API enabled relational database for structural virology. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D436–D442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ceres P, Zlotnick A. 2002. Weak protein-protein interactions are sufficient to drive assembly of hepatitis B virus capsids. Biochemistry 41:11525–11531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chung YC, et al. 2006. Expression, purification and characterization of enterovirus-71 virus-like particles. World J. Gastroenterol. 12:921–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cordell-Stewart B, Taylor MW. 1971. Effect of double-stranded viral RNA on mammalian cells in culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 68:1326–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Curry S, et al. 1997. Dissecting the roles of VP0 cleavage and RNA packaging in picornavirus capsid stabilization: the structure of empty capsids of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 71:9743–9752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dunker AK, Rueckert RR. 1971. Fragments generated by pH dissociation of ME-virus and their relation to the structure of the virion. J. Mol. Biol. 58:217–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Endres D, Zlotnick A. 2002. Model-based analysis of assembly kinetics for virus capsids or other spherical polymers. Biophys. J. 83:1217–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghendon Y, Yakobson E, Mikhejeva A. 1972. Study of some stages of poliovirus morphogenesis in MiO cells. J. Virol. 10:261–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hu YC, Hsu JT, Huang JH, Ho MS, Ho YC. 2003. Formation of enterovirus-like particle aggregates by recombinant baculoviruses co-expressing P1 and 3CD in insect cells. Biotechnol. Lett. 25:919–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jacobson MF, Baltimore D. 1968. Morphogenesis of poliovirus. I. Association of the viral RNA with coat protein. J. Mol. Biol. 33:369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson JM, et al. 2005. Regulating self-assembly of spherical oligomers. Nano Lett. 5:765–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katen SP, Zlotnick A. 2009. Thermodynamics of virus capsid assembly. Methods Enzymol. 455:395–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee PW, Colter JS. 1979. Further characterization of Mengo subviral particles: a new hypothesis for picornavirus assembly. Virology 97:266–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levy HC, Bostina M, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2010. Catching a virus in the act of RNA release: a novel poliovirus uncoating intermediate characterized by cryo-electron microscopy. J. Virol. 84:4426–4441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lewis JK, Bothner B, Smith TJ, Siuzdak G. 1998. Antiviral agent blocks breathing of the common cold virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:6774–6778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li Q, Yafai AG, Lee YM-H, Hogle J, Chow M. 1994. Poliovirus neutralization by antibodies to internal epitopes of VP4 and VP1 results from reversible exposure of these sequences at physiological temperature. J. Virol. 68:3965–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu Y, et al. 2010. Direct interaction between two viral proteins, the nonstructural protein 2CATPase and the capsid protein VP3, is required for enterovirus morphogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001066 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marongiu ME, Pani A, Corrias MV, Sau M, La Colla P. 1981. Poliovirus morphogenesis. I. Identification of 80S dissociable particles and evidence for the artifactual production of procapsids. J. Virol. 39:341–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mukherjee S, Thorsteinsson MV, Johnston LB, DePhillips PA, Zlotnick A. 2008. A quantitative description of in vitro assembly of human papillomavirus 16 virus-like particles. J. Mol. Biol. 381:229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Natarajan P, et al. 2005. Exploring icosahedral virus structures with VIPER. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:809–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nugent CI, Johnson KL, Sarnow P, Kirkegaard K. 1999. Functional coupling between replication and packaging of poliovirus replicon RNA. J. Virol. 73:427–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nugent CI, Kirkegaard K. 1995. RNA binding properties of poliovirus subviral particles. J. Virol. 69:13–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Onodera S, Cardamone JJ, Jr, Phillips BA. 1986. Biological activity and electron microscopy of poliovirus 14S particles obtained from alkali-dissociated procapsids. J. Virol. 58:610–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Onodera S, Phillips BA. 1987. A novel method for obtaining poliovirus 14S pentamers from procapsids and their self-assembly into virus-like shells. Virology 159:278–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Palmenberg AC. 1982. In vitro synthesis and assembly of picornaviral capsid intermediate structures. J. Virol. 44:900–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pettersen EF, et al. 2004. UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Porterfield JZ, Zlotnick A. 2010. A simple and general method for determining the protein and nucleic acid content of viruses by UV absorbance. Virology 407:281–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Putnak JR, Phillips BA. 1981. Picornaviral structure and assembly. Microbiol. Rev. 45:287–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Racaniello VR. 2007. Picornaviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 795–838 In Knipe DM, Howley PM. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rombaut B, Foriers A, Boeye A. 1991. In vitro assembly of poliovirus 14S subunits: identification of the assembly promoting activity of infected cell extracts. Virology 180:781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rombaut B, Vrijsen R, Boeye A. 1984. In vitro assembly of poliovirus empty capsids: antigenic consequences and immunological assay of the morphopoietic factor. Virology 135:546–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rombaut B, Vrijsen R, Delgadillo R, Vanden Berghe D, Boeye A. 1985. Characterization and assembly of poliovirus-related 45 S particles. Virology 146:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smyth M, et al. 1993. Preliminary crystallographic analysis of bovine enterovirus. J. Mol. Biol. 231:930–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smyth M, et al. 1995. Implications for viral uncoating from the structure of bovine enterovirus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:224–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su RT, Taylor MW. 1976. Morphogenesis of picornaviruses: characterization and assembly of bovine enterovirus subviral particles. J. Gen. Virol. 30:317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tang G, et al. 2007. EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 157:38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taylor MW, et al. 1974. Bovine enterovirus-1: characterization, replication and cytopathogenic effects. J. Gen. Virol. 23:173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Verlinden Y, Cuconati A, Wimmer E, Rombaut B. 2000. Cell-free synthesis of poliovirus: 14S subunits are the key intermediates in the encapsidation of poliovirus RNA. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2751–2754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang X, et al. 2012. A sensor-adaptor mechanism for enterovirus uncoating from structures of EV71. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:424–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zell R, Krumbholz A, Dauber M, Hoey E, Wutzler P. 2006. Molecular-based reclassification of the bovine enteroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 87:375–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zlotnick A. 2003. Are weak protein-protein interactions the general rule in capsid assembly? Virology 315:269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zlotnick A. 1994. To build a virus capsid. An equilibrium model of the self assembly of polyhedral protein complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 241:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zlotnick A, Johnson JM, Wingfield PW, Stahl SJ, Endres D. 1999. A theoretical model successfully identifies features of hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. Biochemistry 38:14644–14652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]