Abstract

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an alphavirus which causes chronic and incapacitating arthralgia in humans. Although previous studies have shown that antibodies against the virus are produced during and after infection, the fine specificity of the antibody response against CHIKV is not known. Here, using plasma from patients at different times postinfection, we characterized the antibody response against various proteins of the virus. We have shown that the E2 and E3 glycoproteins and the capsid and nsP3 proteins are targets of the anti-CHIKV antibody response. Moreover, we have identified the different regions in these proteins which contain the linear epitopes recognized by the anti-CHIKV antibodies and determined their structural localization. Data also illustrated the effect of a single K252Q amino acid change at the E2 glycoprotein that was able to influence antibody binding and interaction between the antibodies and epitope because of the changes of epitope-antibody binding capacity. This study provides important knowledge that will not only aid in the understanding of the immune response to CHIKV infection but also provide new knowledge in the design of modern vaccine development. Furthermore, these pathogen-specific epitopes could be used for future seroepidemiological studies that will unravel the molecular mechanisms of human immunity and protection from CHIKV disease.

INTRODUCTION

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), the causative agent for Chikungunya fever (CHIKF), was first described in 1952 during an epidemic in Tanzania, East Africa (21, 34). CHIKV belongs to the genus Alphavirus of the family Togaviridae and is an enveloped virus with a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome (40). Its genome of 12 kb is capped at the 5′ end and polyadenylated at the 3′ end and consists of two open reading frames coding for four nonstructural proteins (nsP1 to nsP4), three structural proteins (capsid, E1, and E2), and two small cleavage products (E3 and 6K) (40, 43). The E1 and E2 glycoproteins form heterodimers that associate as trimeric spikes on the virion surface while the functions of E3 and 6K have yet to be fully defined (28, 10). Nonetheless, it has been proposed that alphavirus E3 is involved in the processing of envelope glycoprotein maturation, whereas alphavirus 6K has been implicated in virus budding (13).

CHIKV is transmitted to humans by means of an arthropod vector such as the Aedes mosquito and results in the development of CHIKF (31). CHIKF is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, rash, myalgia, and severe arthralgia (21, 34). Multiple CHIKF epidemics have occurred in East Africa, the Indian Ocean islands, and many parts of Southeast Asia during the last decade (19, 24, 29, 33).

There is currently no licensed vaccine against CHIKV infection for human use and no effective antiviral agents have been developed thus far. Therapy for CHIKV infection is often limited to supportive care due to problems in specificity and efficacy (43). Nonetheless, recent epidemiological data show increasing evidence for the importance of antibody-mediated protection against CHIKV (14, 15, 46), highlighting the possibility of using anti-CHIKV antibodies in therapeutic or prophylactic treatment. Although the adaptive immune response against CHIKV has yet to be fully characterized, it has been suggested that antibody-mediated protection becomes effective only after several days postinfection (9). Anti-CHIKV IgM antibodies can usually be detected in the patient serum during the acute phase of disease, whereas anti-CHIKV IgG are detected after virus clearance and can persist for several months after infection (9, 14, 42, 44). Furthermore, the establishment of the anti-CHIKV immune response after a primary infection has been inferred to confer complete protection against reinfection (3, 9, 32, 38).

In this present study, we aim to investigate the specificity of anti-CHIKV antibodies induced by primary infection in humans. We show for the first time that the E2 glycoprotein is the main target for the anti-CHIKV antibody response during the entire course of the disease (from the convalescent phase to the recovery phase). One key region within the E2 glycoprotein (N terminus of the E2 glycoprotein proximal to a furin E2/E3-cleavage site) demonstrated a long-lasting seropositive response. Moreover, a single K252Q amino acid change at the E2 glycoprotein was demonstrated by binding assays to have an important effect in antibody binding due to a change in epitope-antibody binding capacity. This naturally acquired mutation disrupted the interaction between the anti-CHIKV antibodies and the specific epitope. More importantly, this is the first comprehensive study whereby multiple linear B-cell epitopes covering the entire CHIKV proteome have been identified directly from anti-CHIKV antibodies obtained from CHIKV-infected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Nine patients, who were admitted with acute CHIKF to the Communicable Disease Centre at Tan Tock Seng Hospital (CDC/TTSH), Singapore, during the outbreak from 1 August to 23 September 2008 (25, 47), were included in this study. Samples from these patients were previously used in a separate study where acute and recovery phases were compared (14). Here we obtained an additional blood sample at a later time point of 21 months after post-illness onset (PIO) to compare with the recovery period. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain-Specific Ethics Review Board (DSRB; reference no. B/08/026).

Cells and virus stocks.

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293T) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Invitrogen). The CHIKV virus isolates (IMT and SGP11) used in this study were originally isolated from a French patient returning from Reunion Island during the 2006 CHIKF outbreak (5) and from Singapore in 2008 at the National University Hospital (11), respectively. Virus stock was prepared via 2 rounds of passages in Vero-E6 cultures, washed, and precleared by sucrose-cushion ultracentrifugation before storage at −80°C. PFU assay and quantitative real-time PCR were utilized to evaluate the virus titers for both isolates.

Recombinant CHIKV plasmids.

Codon-optimized cDNA clones encoding the entire CHIKV proteome (both structural and nonstructural proteins) based on sequence alignments of different CHIKV sequences described previously (15) were synthesized (GenScript Corporation) and subcloned into pDisplay expression vector (Invitrogen) to form pDisplay-nsP1, -nsP2, -nsP3, -nsP4, -capsid (C), -E2, -E1, -E3, and -6K expression plasmids. All positive clones were screened by restriction analysis and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

CHIKV protein expression and immunoblot assay.

Recombinant CHIKV proteins were expressed in HEK 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, with some modifications. Cells were transfected (20 μg of plasmid DNA per 5 × 106 cells) in serum-free DMEM at 32°C for 24 h before refreshment with complete medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS) and incubated for a further 24 h at 32°C. After 48 h, cells were washed with PBS and lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer [20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 280 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40] containing protease inhibitors (20 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO3, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). Cell lysates were mixed with Laemmli buffer and stored at −20°C for Western blot analysis.

Proteins from purified CHIK virions were detected using modified techniques as described previously (6, 16). For reducing sample preparation, equal amounts of IMT and SGP11 viruses quantitated by quantitative real-time PCR and plaque assays were boiled for 5 min at 100°C in Laemmli buffer supplemented with 2% SDS and 1 mM DTT. Nonreducing samples were prepared in Laemmli buffer supplemented with 2% SDS, but without DTT, and were not boiled. SDS migration buffer was used for electrophoresis.

Proteins from CHIK virions and protein lysate preparations were separated by 6% and 10% SDS-PAGE, respectively, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes at 180 mA for 45 min in transfer buffer (24 mM Tris, 77 mM glycine, 20% methanol) using a semidry transfer method. Membranes were blocked overnight in blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 [TBST] supplemented with 5% dry milk and 3% FBS), followed by 1 h of incubation at room temperature with either antihemagglutinin (anti-HA; Invitrogen) or pooled human plasma samples diluted (1:2,000) in blocking buffer. The appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or anti-human IgG secondary antibodies were then added and incubated for 1 h, followed by chemiluminescence detection using ECL Plus detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences). Blots were exposed to films (Pierce, Thermo Scientific) and developed.

Virion-based ELISA and isotyping of CHIKV-infected patient plasma.

Polystyrene 96-well microtiter plates (MaxiSorp; Nunc) were coated with purified CHIKV (20,000 virions per μl in PBS, 50 μl per well). Wells were blocked with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk (PBST-milk), and incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C. Plasma samples were then diluted at 1:100 to 1:2,000 in PBST-milk and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG (Molecular Probe) and the isotype IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 antibodies (Molecular Probe) validated previously for specificity and reactivity (12) were used to detect human antibodies bound to virus-coated wells. Reaction mixtures were developed using TMB (3,3,5,5-tetramethyl benzidine) substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) and terminated by Stop reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Healthy donor samples were used as controls. ELISA readings were done in duplicate, and the values were plotted as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM).

Peptide-based ELISA.

A biotinylated peptide library consisting of 18-mer overlapping peptides (Mimotopes) was generated from sequence alignments of different CHIKV amino acid sequences as described previously (15). Peptides were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain a stock concentration of approximately 15 μg/ml. All peptides were screened in triplicate. Briefly, streptavidin-coated plates (Pierce) were first blocked with 1% sodium caseinate (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in 0.1% PBST (0.1% Tween 20 in PBS) before coating with peptides diluted at 1:1,000 in 0.1% PBST and incubated at room temperature for 1 h on a rotating platform. Plates were then rinsed with 0.1% PBST before incubation with patient plasma samples diluted at 1:2,000 with 0.1% PBST for 1 h. Plates were rinsed, followed by incubation with anti-human IgG antibodies conjugated to HRP diluted in 0.1% blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature to detect peptide-bound antibodies. Readout was detected with TMB substrate solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and terminated with sulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm in a microplate autoreader (Tecan). Peptides are considered positive if absorbance values are higher than the mean ± 3 standard deviation (SD) values of healthy donor controls. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Computational modeling.

Structural data of the glycoproteins were retrieved from Protein Data Bank (PDB) (identifiers 3N44 and 2XFB) and visualized using the UCSF CHIMERA software (30). Solvent excluded molecular surfaces were generated with the help of MSMS package (37). Structures of capsid and nsP3 sequences were predicted separately using individual I-TASSER queries, and visualized using UCSF Chimera software (30, 36, 48).

In vitro neutralization.

Neutralizing activity of antibodies from CHIKV-infected patient samples were tested in triplicate and analyzed by immunofluorescence-based cell infection assay in HEK 293T cells. CHIKV was mixed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10, with either heat-inactivated human plasma or healthy donor plasma (between 1:500 and 1:8,000, in 2-fold dilutions), and incubated for 2 h at 37°C, with gentle agitation in a thermomixer. Virus-antibody mixtures were then added to HEK 293T cells seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C. Medium was removed, and cells were replenished with DMEM medium supplied with 5% FBS and incubated for 6 h at 37°C before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by immunofluorescence quantification using the Cellomics ArrayScan V. The percentage of infectivity was calculated according to the following equation: % infectivity = 100 × (% responder from seroneutralization group/% responder from virus infection group).

Statistics.

All data are presented as means ± SEM or SD. Differences in responses among groups at various time points and between groups and controls were analyzed using appropriate statistical tests (Mann-Whitney U test, two-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test). A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Analysis of antibody response to CHIKV after a primary infection in humans.

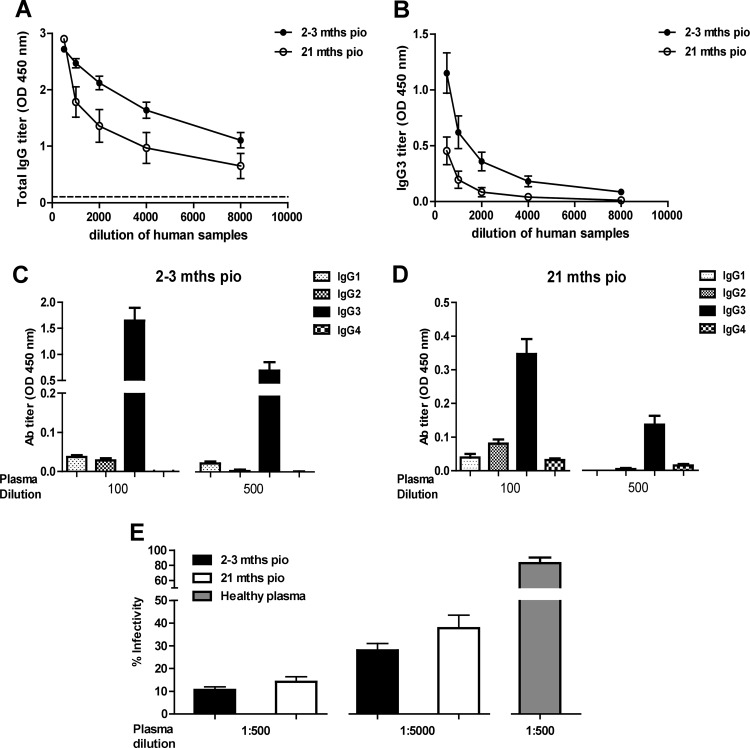

In order to characterize the anti-CHIKV antibody response after the infection has cleared, we obtained samples taken at two different postinfection time points from 9 patients who were admitted for acute CHIKF during an outbreak in Singapore in late 2008 (25, 47). The total IgG present in the plasma from each patient was quantified by the SGP11 virion-based ELISA. High levels of anti-SGP11 CHIKV-specific IgG antibody responses were detected at 2 to 3 months PIO (Fig. 1A), confirming our previous results (14). However, even though the IgG levels decreased over time, they were still detectable at 21 months PIO (Fig. 1A). IgG3 was the predominant isotype in the patient plasma samples (Fig. 1B, 1C and 1D). Plasma samples from each of these patients contained antibodies that displayed neutralizing activity when assessed in seroneutralization assays, with the highest efficacy for samples taken at 2 to 3 months PIO (Fig. 1E). The neutralizing activity of these antibodies from CHIKV-infected patient plasma was sustained until 21 months PIO, even at different plasma dilutions (Fig. 1E).

Fig 1.

Antibody profiles and neutralizing capacity of CHIKV-infected patient plasma samples. (A) Virus-specific IgG antibody titers in each plasma sample (n = 9) was determined by ELISA using purified CHIKV virions. CHIKV-infected patient plasma samples from the CHIKF outbreak in Singapore between 2008 and 2009 (2 to 3 months and 21 months PIO) assayed by serial dilution and subjected to virion-based ELISA using 96-well plates precoated with purified SGP11 virions. Healthy donor plasma and no-plasma samples were used as negative controls. (B) Virus-specific IgG3 isotype titer in serially diluted patient plasma samples was determined individually by ELISA using purified CHIKV virions. Each point represents mean ± SEM of 9 individual samples from the cohorts. (C and D) Virus-specific IgG isotype titer in individual plasma samples were determined at dilutions of 1:100 and 1:500 using specific secondary antibodies. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 9 patient samples and are representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (E) In vitro neutralizing activity against CHIKV-infected plasma samples. Same set of patient plasma samples (2 to 3 months and 21 months PIO) were tested individually in triplicate at dilutions of 1:500 and 1:5,000. Results are expressed as percentage of control infection. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 9 patient samples and are representative of 3 independent experiments. Dotted straight line represents healthy donor plasma and was used as a control.

Antigen recognition by CHIKV-infected patient samples.

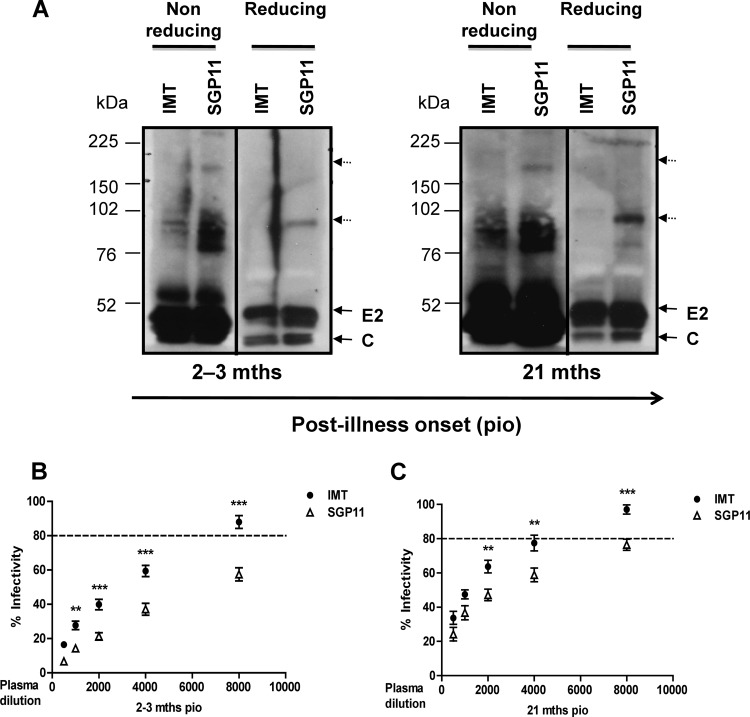

CHIK virions were purified from the supernatants of cells infected with CHIKV originating from Reunion Island (IMT) (5) or from Singapore (SGP11) (11). Protein extracts were isolated under reducing and nonreducing conditions as described previously (6, 16) and were then assessed by immunoblot analysis with the patient plasma samples (Fig. 2A). This first crude screen revealed that these samples contained antibodies which recognized multiple protein fractions of CHIKV and that the reactivity increased steadily over time. A stronger reactivity against proteins under nonreducing conditions compared to proteins under reducing conditions indicated that the plasma samples contained antibodies recognizing both linear and conformational epitopes (8). In addition, reactivity was stronger with SGP11 CHIKV than with IMT CHIKV, suggesting that polymorphic epitopes presented between SGP11 and IMT are recognized by a fraction of human antibodies. Interestingly, this stronger reactivity was associated with a significantly stronger neutralizing activity against SGP11 than against IMT for all patients at both 2 to 3 months and 21 months PIO (Fig. 2B and C), reflecting that these patients were infected with viruses with sequences that are closely related to the SGP11 virus isolate.

Fig 2.

Anti-CHIKV antibodies demonstrate polymorphic epitopes recognition and show differential neutralizing capacities against different CHIKV isolates. (A) Purified CHIK virions from IMT and SGP11 were prepared under reducing (100°C for 5 min with DTT) and nonreducing conditions and subjected to SDS-PAGE gel and probed with pooled plasma at an optimized dilution of 1:5,000, followed by secondary anti-human IgG-HRP. Sizes of molecular weight markers are indicated in the left part of the diagram. The dotted arrows indicate the high-molecular-weight complexes detected by CHIKV-infected patient plasma. (B and C) In vitro neutralizing activity against CHIKV-infected plasma samples. Individual plasma samples (2 to 3 months and 21 months PIO) were tested against either IMT or SGP11 viruses in triplicate at dilutions between 1:500 and 1:8,000 (2-fold dilutions). Results are expressed as percentage of control infection. **, P < 0.01, and ***, P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 9 patient samples and are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. Dotted straight lines represent the percentage of control infection of either IMT or SGP11, premixed with healthy donor's samples.

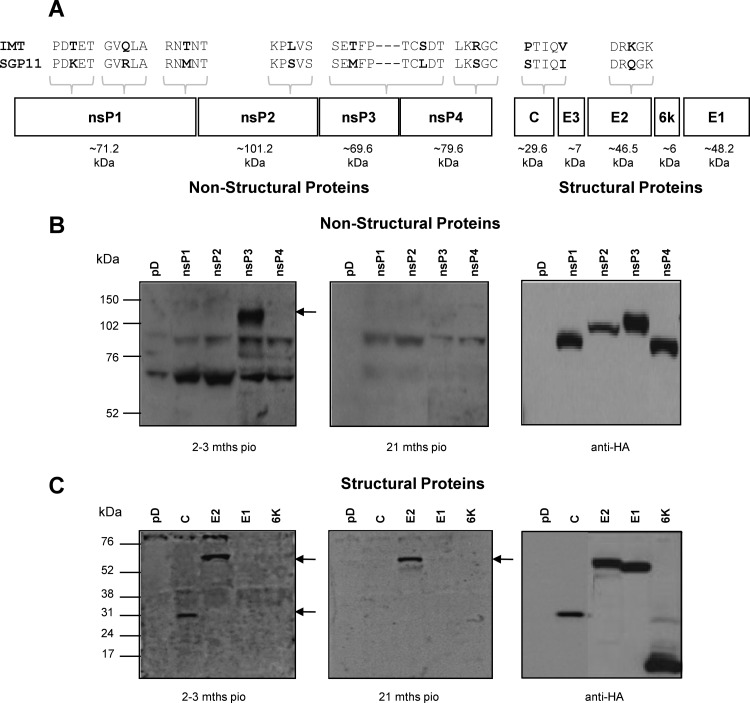

To better define the antigenic recognition profile of the antibodies from these patient plasma samples, we generated expression plasmids encoding CHIKV proteins (Fig. 3A) tagged with a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope. After transient transfection in HEK 239T cells, all but E3 proteins were successfully expressed, as shown by Western blot analysis using antibodies against HA (Fig. 3B and 3C, right panel). Using cell lysates from the different transfectants, we further determined which of these antigens were specifically recognized by antibodies present in patient plasma (Fig. 3B and C). Of the nonstructural proteins (nsPs), only nsP3 was recognized by the plasma samples taken at 2 to 3 months PIO (Fig. 3B, left panel). However, at 21 months PIO, patients did not have any more anti-nsP3 antibodies (Fig. 3B, middle panel). Patient plasma also contained antibodies against E2 glycoprotein and capsid protein (Fig. 3C, left panel). However, only anti-E2 antibodies persisted until 21 months PIO (Fig. 3C, middle panel).

Fig 3.

Antigenic recognition profiles of the anti-CHIKV antibodies. (A) Schematic representation of CHIKV proteome. Differences at the amino acid level between the isolates (IMT and SGP11) are shown. (B) Total cell lysates were prepared from transiently expressed nonstructural protein 1 (nsP1), nonstructural protein 2 (nsP2), nonstructural protein 3 (nsP3), and nonstructural protein 4 (nsP4). (C) Total cell lysates were prepared from transiently expressed capsid protein (C), E2 glycoprotein (E2), E1 glycoprotein (E1), and 6K protein. Lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and probed with pooled plasma at a dilution of 1:2,000, followed by secondary anti-human IgG-HRP. Control cell lysates were prepared from cells transiently transfected with pDisplay (pD) plasmids. The antigens recognized by CHIKV-infected patient plasma are indicated by solid arrows.

Mapping of CHIKV protein regions recognized by human antibodies.

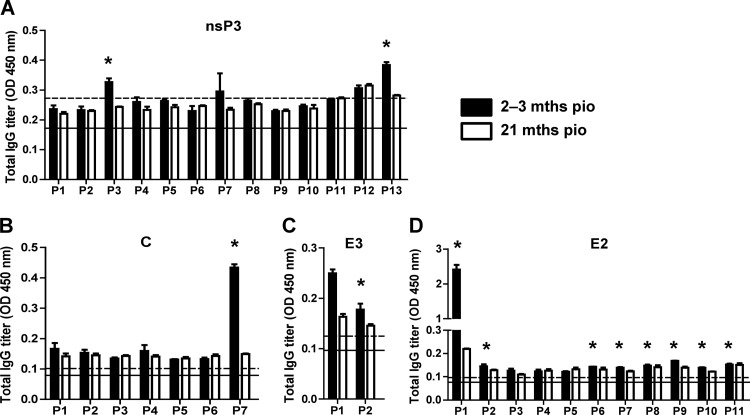

Peptide-based ELISAs using a peptide library (Mimotopes) consisting of 18-mer overlapping biotinylated peptides covering the whole CHIKV proteome were performed with pooled plasma samples using an optimized plasma dilution established for these assays (15). Complete data from the two different time points are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 1. Interestingly, two linear epitope-containing regions of the nsP3 protein (Fig. 4A), one region in the capsid protein (Fig. 4B), one region in the E3 glycoprotein (Fig. 4C), and several regions in the E2 glycoprotein (Fig. 4D) were identified.

Fig 4.

Mapping of CHIKV B-cell epitopes within the CHIKV proteome by CHIKV-infected patient samples. Pooled CHIKV-infected patient plasma (2 to 3 months and 21 months PIO), at an optimized dilution of 1:2,000, were subjected to peptide-based ELISA covering the CHIKV proteome consisting of the nonstructural nsP3 protein (A) and the structural capsid, E3, and E2 proteins (B to D) using pooled peptides. Healthy donor plasma and no-plasma samples were used as negative controls. Solid black line represents the mean value of the healthy donors; dotted line represents the value of mean ± 3 SD. *, significant values above mean ± 3 SD are considered positive. Results represent an average of 2 independent experiments (mean ± SD).

Table 1.

Peptide pools for mapping of CHIKV B-cell epitopes within the CHIKV proteome

| Viral antigen | Peptide pool annotation | Polypeptide sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| nsP3 | P1 | 1329–1370 |

| P2 | 1361–1410 | |

| P3 | 1401–1450 | |

| P4 | 1441–1490 | |

| P5 | 1481–1530 | |

| P6 | 1521–1570 | |

| P7 | 1561–1610 | |

| P8 | 1601–1650 | |

| P9 | 1641–1690 | |

| P10 | 1681–1730 | |

| P11 | 1721–1770 | |

| P12 | 1761–1810 | |

| P13 | 1801–1863 | |

| Capsid | P1 | 2475–2524 |

| P2 | 2505–2554 | |

| P3 | 2545–2594 | |

| P4 | 2585–2634 | |

| P5 | 2625–2674 | |

| P6 | 2665–2714 | |

| P7 | 2705–2735 | |

| E3 | P1 | 2736–2785 |

| P2 | 2776–2799 | |

| E2 | P1 | 2800–2842 |

| P2 | 2833–2882 | |

| P3 | 2873–2922 | |

| P4 | 2913–2962 | |

| P5 | 2953–3002 | |

| P6 | 2993–3042 | |

| P7 | 3033–3082 | |

| P8 | 3073–3122 | |

| P9 | 3113–3162 | |

| P10 | 3153–3202 | |

| P11 | 3193–3222 |

The numbers correspond to the amino acid positions along the CHIKV viral genome. The first amino acid from nsP1 is annotated as 1.

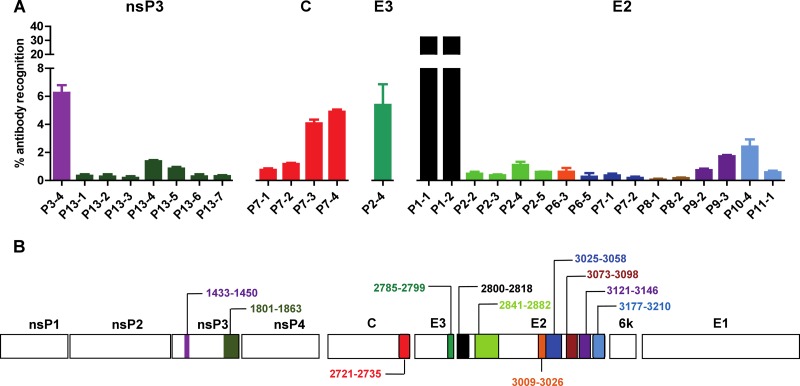

To define the location of these linear epitopes, plasma samples were next tested with the complete set of single peptides from each of the selected active pools (Fig. 5A). Results were expressed as the percentage of antibody recognition within the whole CHIKV proteome. We found that the antibodies strongly recognized the dominant linear epitope on the E2 glycoprotein (E2 P1-1 and P1-2), which corresponded to the linear E2EP3 epitope previously identified from patient plasma taken at a much earlier time point (15). nsP3 protein, capsid protein, and E3 glycoprotein have corresponding dominant linear epitopes within the viral proteins and possess about 6% of antibody recognition. Their positions within the nonstructural and structural proteins relative to the whole CHIKV genome are illustrated in the schematic diagrams (Fig. 5B and Table 2). The single recognized segment for the capsid protein is located at the C terminus of the protein, while epitopes for the E2 glycoprotein are distributed along the entire viral protein. On the other hand, no linear regions in the 6K protein and E1 glycoprotein were recognized by the patient plasma. Comparison of the reactivity between the two time points showed that antibodies recognizing the linear epitopes in nsP3 protein, capsid protein, and E3 glycoprotein did not persist (Fig. 4). Surprisingly, antibodies from all patients against the immunodominant region E2-P1 or E2EP3 epitope (15) are still present after 21 months PIO (Fig. 4D).

Fig 5.

Analysis of anti-CHIKV antibodies recognition with CHIKV linear B-cell epitopes. (A) Pooled CHIKV-infected patient plasma (2 to 3 months PIO), at an optimized dilution of 1:2,000, were subjected to peptide-based ELISA covering the CHIKV genome encoding the nonstructural and structural proteins using individual peptides. (B) Genome organization encoding the nonstructural and structural proteins of CHIKV. Regions of amino acids corresponding to the identified B-cell epitopes are shown. Healthy donor plasma and no-plasma samples were used as negative controls. Results represent an average of 2 independent experiments (mean ± SD). Percentage of antibody recognition was calculated according to the following equation: % antibody recognition = 100 × (OD values from individual peptide group/sum of OD values from all peptide groups).

Table 2.

Individual peptides for mapping of CHIKV B-cell epitopes within the CHIKV proteome

| Viral antigen | Individual peptide annotation | Polypeptide sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| nsP3 | P3-4 | 1433–1450 |

| P13-1 | 1801–1818 | |

| P13-2 | 1809–1826 | |

| P13-3 | 1817–1834 | |

| P13-4 | 1825–1842 | |

| P13-5 | 1833–1850 | |

| P13-6 | 1841–1858 | |

| P13-7 | 1849–1863 | |

| Capsid | P7-1 | 2705–2722 |

| P7-2 | 2713–2730 | |

| P7-3 | 2721–2735 | |

| P7-4 | 2729–2735 | |

| E3 | P2-4 | 2785–2799 |

| E2 | P1-1 | 2800–2810 |

| P1-2 | 2801–2818 | |

| P2-2 | 2841–2858 | |

| P2-3 | 2849–2866 | |

| P2-4 | 2857–2874 | |

| P2-5 | 2865–2882 | |

| P6-3 | 3009–3026 | |

| P6-5 | 3025–3042 | |

| P7-1 | 3033–3050 | |

| P7-2 | 3041–3058 | |

| P8-1 | 3073–3090 | |

| P8-2 | 3081–3098 | |

| P9-2 | 3121–3138 | |

| P9-3 | 3129–3146 | |

| P10-4 | 3177–3194 | |

| P11-1 | 3193–3210 |

The numbers correspond to the amino acid positions along the CHIKV viral genome. The first amino acid from nsP1 is annotated as 1.

Essentially, results from the peptide-based ELISAs were consistent with the Western blot analyses, confirming the recognized regions in the nsP3 protein, the E2 glycoprotein, and the capsid protein.

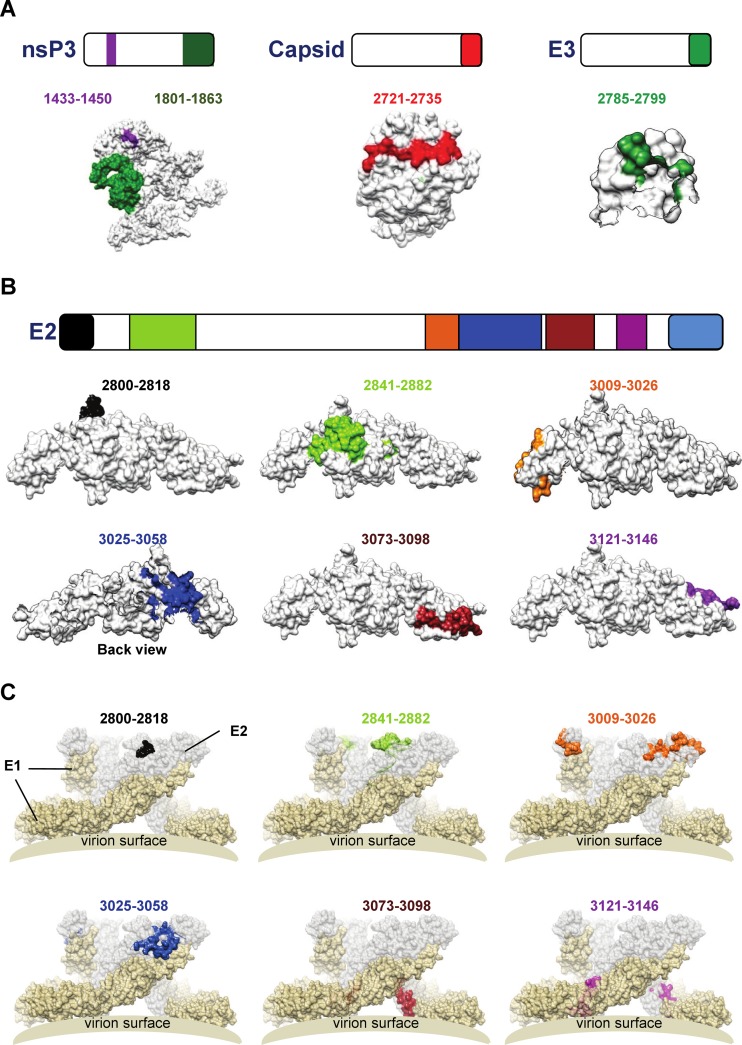

Structural localization of the antigenic regions recognized by human antibodies.

Epitope-containing sequences were subsequently mapped onto the available three-dimensional (3D) crystal structures of the E3 and E2 glycoproteins (PDB identifier 3N44) or predicted 3D structures of the capsid and nsP3 proteins (36, 48). The unique epitope-containing segment of the capsid protein is located in a solvent-exposed region (Fig. 6A). The same is true for the single recognized segment of the E3 glycoprotein (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, structural analyses also showed that the identified E3 segment is situated near the furin cleavage site that releases the E2 and E3 glycoproteins during the maturation process of the precursor protein (26). Similarly, the two segments of the nsP3 protein are also located in a solvent-exposed region (Fig. 6A).

Fig 6.

Localization of CHIKV B-cell epitopes within the CHIKV proteome. (A) Schematic representation of identified B-cell epitopes in nsP3, capsid, and E3 proteins. (B) Schematic representation of identified B-cell epitopes in E2 glycoprotein. Epitopes in the E3 and E2 glycoproteins were located based on structural data retrieved from PDB records (identifier 3N44). Epitopes in the capsid and nsP3 proteins were located based on structures predicted by the I-TASSER server. (C) Schematic diagram showing the localization of identified E2 glycoprotein B-cell epitopes in the protein complex situated at the surface of the virus based on structural data retrieved from PDB records (identifier 2XFB). Spatial arrangement of E1 glycoprotein (in pale-yellow color) and E2 glycoprotein (in light-gray color) on the viral membrane surface are shown accordingly.

Similar analyses for the E2 glycoprotein revealed that 6 out of 7 segments mapped to the solvent-exposed region (Fig. 6B and C). Although these epitopes are located along the E2 glycoprotein, the majority of them are clustered at the C terminus. The structure of the segment, contained between amino acid positions 3177 and 3210, located at the C-terminal of the E2 glycoprotein, could not be resolved.

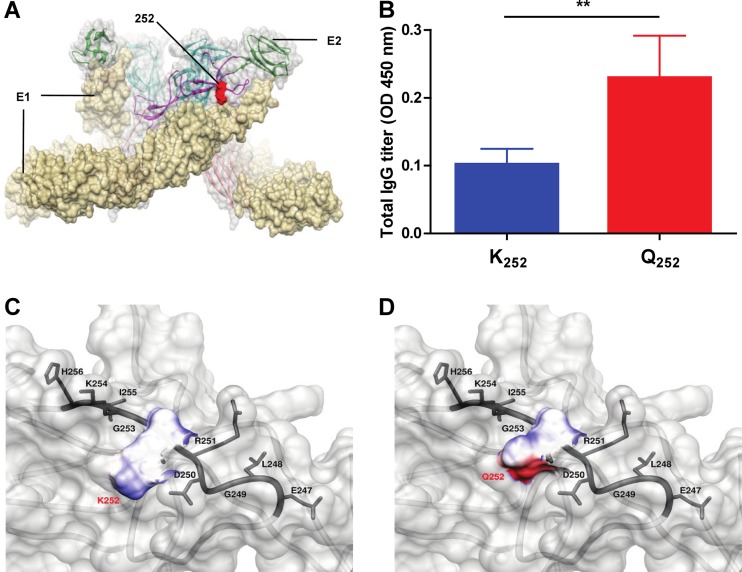

A single K252Q amino acid change at E2 glycoprotein may alter antibody recognition.

As shown in Fig. 2, the patient antibodies were able to detect higher molecular weight complexes under nondenaturing conditions. This recognition was stronger for the SGP11 isolate than for the IMT isolate, suggesting that there may be conformational differences in antibody binding between the two virus isolates. Therefore, deep-sequencing analysis was carried out to identify potential sequence differences at the amino acid level. Results revealed a single amino acid difference at position 252 in the E2 glycoprotein (Fig. 7A) that is positioned within one of the identified B-cell epitope (between amino acids 3025 and 3058) (Fig. 6B). This single amino acid residue difference could contribute to the differential binding capacity of patient plasma antibodies to various CHIKV isolates, as the amino acid change at position 252 of E2 from lysine (K from IMT) to glutamine (Q from SGP11) resulted in a change in amino acid property from electrically charged to polar uncharged side chains. This observation was further demonstrated by experiments performed with patient plasma samples using synthetic peptides of this identified B-cell epitope, encoding K252 (IMT isolate) and Q252 (SGP11 isolate). We found that antibodies recognized the peptide containing Q252 more efficiently than the peptide containing K252 (Fig. 7B). Moreover, CHIKV-infected patient plasma from this cohort also showed stronger neutralizing capacity against CHIKV carrying Q252 (SGP11 isolate) than CHIKV carrying K252 (IMT isolate) (Fig. 2B). This provides key information in the formulation of CHIKV vaccines that will include important specific amino acid residues involved in the recognition of anti-CHIKV antibodies.

Fig 7.

Localization of amino acid residues Q and K at position 252 of the CHIKV E2 glycoprotein. (A) Schematic diagram showing the localization of amino acid residue 252 in the E1-E2 glycoprotein complex based on structural data retrieved from PDB records (identifier 2XFB) shows the spatial arrangement of E1 glycoprotein (in pale-yellow color) and E2 (in light-gray color) glycoprotein on the viral membrane surface. (B) Biotinylated synthetic peptides encoding the K252 (VPRNAELGDRKGKIHIPF) and Q252 (VPRNAELGDRQGKIHIPF) amino acid residues were screened with CHIKV-infected patient plasma (2 to 3 months PIO) at an optimized dilution of 1:2,000. Healthy donor plasma was used as a negative control. Data are expressed as optical density (OD) with background signals (healthy donor plasma) subtracted. Results are presented as mean ± SD and are representative of 3 independent experiments. **, P < 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test. (C and D) Enlarged images to illustrate the surface electrostatic potential of K252 and Q252, respectively, in their spatial relation to amino acid residues in the vicinity. The electrostatic potential map is colored blue and red, corresponding to positive and negative surface potentials, respectively.

The surface charge distribution of E2 glycoprotein was further investigated in detail by computational modeling. The amino acid change at position 252 was shown to result in a change in surface charge distribution from neutral to negative (Fig. 7C and D). Thus, patient antibodies preferably recognize this region of the E2 glycoprotein that possessed an amino acid with a negatively charged region (Q252 from SGP11). This negatively charged region on Q252 is attributed to the presence of the double-bonded carbonyl oxygen (C O) in the terminal amide (CONH2) group of glutamine's side chain. Therefore, this oxygen atom could then potentially form a new hydrogen (H) bond by accepting a bonded proton (X-H or H bond donor), which would not be possible with the lysine side chain. As a result, a loss of electrostatic interaction between patient antibodies and K252 could have resulted in weaker binding capacity against the IMT isolate.

O) in the terminal amide (CONH2) group of glutamine's side chain. Therefore, this oxygen atom could then potentially form a new hydrogen (H) bond by accepting a bonded proton (X-H or H bond donor), which would not be possible with the lysine side chain. As a result, a loss of electrostatic interaction between patient antibodies and K252 could have resulted in weaker binding capacity against the IMT isolate.

DISCUSSION

An understanding of the antibody response against CHIKV is important for the development of diagnostic tools and potential vaccine candidates. Here, we have performed the first comprehensive and longitudinal analysis of the antibody response against CHIKV linear determinants. Although the antibody response to CHIKV targets both linear (15) and conformational epitopes (20) (Fig. 2A), in this study, we focused on linear determinants since they are more easily identifiable in a medium-throughput approach. Using patient plasma samples from the CHIKF outbreaks in Singapore (25, 47), we first observed that the antibody response against linear determinants was attributed to a persisting IgG3 response that was detectable even at 21 months PIO. Under the experimental conditions used, we next showed that only 3 structural proteins (capsid protein and E2 and E3 glycoproteins) and one nonstructural protein (nsP3) contained linear epitopes recognized by patient anti-CHIKV antibodies. Antibody responses against most of these protein determinants were high at 2 to 3 months PIO but progressively waned. Only the response against E2 glycoprotein was still detectable at 21 months PIO. This long-lasting response against the N-terminal region of the E2 glycoprotein (between amino acids 2800 and 2818) makes it an attractive candidate for seroepidemiology studies. We have previously mapped a B-cell epitope in this region. High levels of antibodies detected against this epitope, E2EP3, during the CHIKV acute phase was shown to be associated with long-term clinical protection (14, 15). With this finding, an E2EP3-based ELISA could be used to study previous CHIKV infections to determine the magnitude of outbreaks.

Although neutralizing antibodies against linear epitopes of the E2 glycoprotein have been reported (14, 15), it is not known if such epitopes exist in other surface-exposed viral proteins and in other alphaviruses such as Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) and Sindbis virus (SINV) (35, 39). The C-terminal regions of both the capsid protein and the E3 glycoprotein were identified by patient plasma. Detailed analysis of both 3D structures showed that these regions are solvent accessible (Fig. 6). Antibodies directed against the E3 glycoprotein have been shown to protect mice against infections from Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, a closely related alphavirus (27). Thus, the exact definition of the CHIKV E3 glycoprotein epitope recognized by CHIKV-infected patients deserves further study in order to assess their potential as a target for neutralizing antibodies (27). Since the capsid protein is enclosed inside the virions, it is likely to be protected from the action of neutralizing antibodies.

Of the nonstructural proteins, only CHIKV nsP3 was recognized by the anti-CHIKV antibodies under the experimental conditions used. This may reflect the biological specificity of these different nonstructural proteins. CHIKV nsP1, like nsP1 of other alphaviruses (1, 2), interacts preferentially with host lipids (2, 18) and may thus be sheltered from immune detection and recognition (7). On the other hand, nsP2 and nsP4 were recently demonstrated to interact with a wide range of host proteins that may shelter them from immune detection (7). Although the functions and activities of nsP3 protein are less well defined, it was reported that the C-terminal region of CHIKV nsP3 is intrinsically disordered and may favor recognition by B-cell receptors that are present on specific B cells (7). The 6K protein was also not recognized. This protein is thought to form ion pore channels and could be inserted into host cell plasma membrane (23). As a result, regions within this molecule may be protected from recognition by the immune system and inaccessible to antibodies. It has been demonstrated recently that CHIKV induces apoptosis in infected cells and that the apoptotic blebs containing CHIKV facilitate infection of new cells in a noninflammatory manner (17). Hence, this would limit the presentation of CHIKV antigens solely expressed in host cells.

Here, immunoblot assays showed that the patient antibodies reacted more strongly with CHIKV proteins under nonreducing conditions. This demonstrates evidently that the patients had anti-CHIKV antibodies that recognized other conformational epitopes. It is likely that these anti-CHIKV antibodies also recognized epitopes in other surface viral antigens such as the E1, E2, or E3 glycoproteins as suggested previously (20). Interestingly, patient anti-CHIKV antibodies were shown to bind more strongly to SGP11 than IMT. Computational analysis revealed that this phenomenon could be due to a loss of epitope-antibody binding capacity when the amino acid at position 252 is changed from Q to K between SGP11 and IMT. Binding experiments further revealed the differential binding capacity of patient plasma antibodies to different CHIKV isolates with different epitope sequences. Furthermore, seroneutralization assays performed at higher dilutions of patient plasma demonstrated differential neutralizing activities between the two different CHIKV isolates (Fig. 2). This not only confirms the important role of amino acid residue 252 in determining antigen-antibody recognition, but this residue also affects the antibody-mediated neutralization efficiency. Furthermore, the K252Q mutation was also reported as one of the genomic signatures for some strains of CHIKV isolates (41). The existence of CHIKV carrying either K252 or Q252 within the population could be an indication of host adaptation (45).

More recently, a different study reported the importance of acid-sensitive regions (ASRs) in regulating neutralizing antibody recognition and conformational changes (4). In support of our study, they also showed a role for amino acid residue 252 in regulating CHIKV replication (4). Furthermore, one of the ASRs (between amino acids 231 and 258) matched with one of our identified B-cell epitopes (between amino acids 3025 and 3058), verifying our data on the role of this epitope in antibody binding. Together, these observations strongly implicate the importance of interactions between specific antibodies and corresponding peptides at the amino acid level (22), providing key information in optimizing CHIKV vaccine development with important specific amino acid residues in anti-CHIKV antibody recognition. To optimize the coverage of CHIKV vaccine formulation, B-cell epitopes from both virus isolates could be incorporated in a virus-like particle expression system.

In conclusion, we showed that multiple linear regions within the CHIKV proteome are recognized by specific anti-CHIKV antibodies from primo-infected individuals. Validation of epitopes in multiple patient cohorts in different geographical backgrounds may define certain signatures that will be useful and important in the development of serodiagnosis assays and vaccine development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jeslin J. L. Tan (SIgN) for technical assistance and Marc Grandadam (IRBA-IMTSSA, France) for providing us with the viral strain from Reunion Island. We thank all the staff at the Communicable Diseases Centre, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, involved in patient recruitment and at the Health Sciences Authority of Singapore for supply of healthy donor blood. We thank Josephine Lum and Francesca Zolezzi (Functional Genomics Group, SIgN, Singapore) for their technical assistance in the deep sequencing analysis and Michael Poidinger (Bioinformatics Group, SIgN, Singapore) for data analysis.

This study was supported by the Biomedical Research Council (BMRC) and by a research grant from the Joint Council Office (JCO), A*STAR.

We have no financial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahola T, Lampio A, Auvinen P, Kaariainen L. 1999. Semliki Forest virus mRNA capping enzyme requires association with anionic membrane phospholipids for activity. EMBO J. 18:3164–3172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahola T, et al. 2000. Effects of palmitoylation of replicase protein nsP1 on alphavirus infection. J. Virol. 74:6725–6733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akahata W, et al. 2010. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat. Med. 16:334–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akahata W, Nabel GJ. 2012. A specific domain of the Chikungunya virus E2 protein regulates particle formation in human cells: implications for alphavirus vaccine design. J. Virol. doi:10.1128/JVI.00370–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bessaud M, et al. 2006. Chikungunya virus strains, Reunion Island outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1604–1606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Beasley DW, Fitzpatrick DR, Aaskov JG. 1997. Analysis of a recombinant dengue-2 virus-dengue-3 virus hybrid envelope protein expressed in a secretory baculovirus system. J. Gen. Virol. 78:2723–2733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bourai M, et al. 2012. Mapping of Chikungunya virus interactions with host proteins identified nsP2 as a highly connected viral component. J. Virol. 86:3121–3134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conway JF, et al. 2003. Characterization of a conformational epitope on hepatitis B virus core antigen and quasiequivalent variations in antibody binding. J. Virol. 77:6466–6473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Couderc T, et al. 2009. Prophylaxis and therapy for Chikungunya virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 200:516–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Firth AE, Chung BY, Fleeton MN, Atkins JF. 2008. Discovery of frameshifting in Alphavirus 6K resolves a 20-year enigma. Virol. J. 5:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Her Z, et al. 2010. Active infection of human blood monocytes by Chikungunya virus triggers an innate immune response. J. Immunol. 184:5903–5913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jefferis R, et al. 1985. Evaluation of monoclonal antibodies having specificity for human IgG sub-classes: results of an IUIS/WHO collaborative study. Immunol. Lett. 10:223–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jose J, Snyder JE, Kuhn RJ. 2009. A structural and functional perspective of alphavirus replication and assembly. Future Microbiol. 4:837–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kam YW, et al. 2012. Early appearance of neutralizing immunoglobulin G3 antibodies is associated with chikungunya virus clearance and long-term clinical protection. J. Infect. Dis. 205:1147–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kam YW, et al. 2012. Early neutralizing IgG response to Chikungunya virus in infected patients targets a dominant linear epitope on the E2 glycoprotein. EMBO Mol. Med. 4:330–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kam YW, et al. 2007. Antibodies against trimeric S glycoprotein protect hamsters against SARS-CoV challenge despite their capacity to mediate FcgammaRII-dependent entry into B cells in vitro. Vaccine 25:729–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krejbich-Trotot P, et al. 2011. Chikungunya virus mobilizes the apoptotic machinery to invade host cell defenses. FASEB J. 25:314–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laakkonen P, Ahola T, Kaariainen L. 1996. The effects of palmitoylation on membrane association of Semliki forest virus RNA capping enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 271:28567–28571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lam SK, et al. 2001. Chikungunya infection–an emerging disease in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 32:447–451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee CY, et al. 2011. Chikungunya virus neutralization antigens and direct cell-to-cell transmission are revealed by human antibody-escape mutants. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lumsden WH. 1955. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. II. General description and epidemiology. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 49:33–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McLellan JS, et al. 2011. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature 480:336–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melton JV, et al. 2002. Alphavirus 6K proteins form ion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 277:46923–46931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Munasinghe DR, Amarasekera PJ, Fernando CF. 1966. An epidemic of dengue-like fever in Ceylon (chikungunya—a clinical and haematological study. Ceylon Med. J. 11:129–142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ng KW, et al. 2009. Clinical features and epidemiology of chikungunya infection in Singapore. Singapore Med. J. 50:785–790 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ozden S, et al. 2008. Inhibition of Chikungunya virus infection in cultured human muscle cells by furin inhibitors: impairment of the maturation of the E2 surface glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 283:21899–21908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parker MD, et al. 2010. Antibody to the E3 glycoprotein protects mice against lethal Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection. J. Virol. 84:12683–12690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parrott MM, et al. 2009. Role of conserved cysteines in the alphavirus E3 protein. J. Virol. 83:2584–2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pavri K. 1986. Disappearance of Chikungunya virus from India and South East Asia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80:491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pettersen EF, et al. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Powers AM, Logue CH. 2007. Changing patterns of chikungunya virus: re-emergence of a zoonotic arbovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 88:2363–2377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Queyriaux B, et al. 2008. Clinical burden of chikungunya virus infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8:2–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Renault P, et al. 2007. A major epidemic of chikungunya virus infection on Reunion Island, France, 2005–2006. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77:727–731 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Robinson MC. 1955. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. I. Clinical features. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 49:28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roehrig JT, Mathews JH. 1985. The neutralization site on the E2 glycoprotein of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis (TC-83) virus is composed of multiple conformationally stable epitopes. Virology 142:347–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. 2010. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Protoc. 5:725–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sanner MF, Olson AJ, Spehner JC. 1996. Reduced surface: an efficient way to compute molecular surfaces. Biopolymers 38:305–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schuffenecker I, et al. 2006. Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 3:e263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Strauss EG, Stec DS, Schmaljohn AL, Strauss JH. 1991. Identification of antigenically important domains in the glycoproteins of Sindbis virus by analysis of antibody escape variants. J. Virol. 65:4654–4664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Strauss JH, Strauss EG. 1994. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 58:491–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Suwannakarn K, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan Y. 2011. Molecular genome tracking of East, Central and South African genotype of Chikungunya virus in South-east Asia between 2006 and 2009. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 4:535–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tandale BV, et al. 2009. Systemic involvements and fatalities during Chikungunya epidemic in India, 2006. J. Clin. Virol. 46:145–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Teng TS, Kam YW, Tan JL, Ng LF. 2011. Host responses to Chikungunya virus and perspectives for immune-based therapies. Future Virol. 6:975–984 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Theamboonlers A, Rianthavorn P, Praianantathavorn K, Wuttirattanakowit N, Poovorawan Y. 2009. Clinical and molecular characterization of chikungunya virus in South Thailand. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 62:303–305 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsetsarkin KA, et al. 2009. Epistatic roles of E2 glycoprotein mutations in adaption of chikungunya virus to Aedes albopictus and Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS One 4:e6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Warter L, et al. 2011. Chikungunya virus envelope-specific human monoclonal antibodies with broad neutralization potency. J. Immunol. 186:3258–3264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Win MK, Chow A, Dimatatac F, Go CJ, Leo YS. 2010. Chikungunya fever in Singapore: acute clinical and laboratory features, and factors associated with persistent arthralgia. J. Clin. Virol. 49:111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang Y. 2008. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 9:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]