Abstract

One common sign of human cytomegalovirus infection is altered liver function. Murine cytomegalovirus strain v70 induces a rapid and severe hepatitis in immunocompetent mice that requires the presence of T cells in order to develop. v70 exhibits approximately 10-fold-greater virulence than the commonly used strain K181, resulting in a more severe, sustained, and lethal hepatitis but not dramatically higher viral replication levels. Hepatitis and death are markedly delayed in immunodeficient SCID compared to immunocompetent BALB/c mice. Transfer of BALB/c splenocytes to SCID mice conferred rapid disease following infection, and depletion of either CD4 or CD8 T cells in BALB/c mice reduced virus-induced hepatitis. The frequency of CD8 T cells producing gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor in response to viral antigen was higher in settings where more severe disease occurred. Thus, virus-specific effector CD8 T cells appear to contribute to lethal virus-induced hepatitis, contrasting their protective role during sublethal infection. This study reveals how protection and disease during cytomegalovirus infection depend on viral strain and dose, as well as the quality of the T cell response.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) disease is associated with liver dysfunction. Hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice are two signs of systemic congenital disease (21, 28). Cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease in solid-organ and hematopoietic-allograft recipients is a leading cause of graft loss and mortality where elevated liver enzymes and hepatitis are common (1, 10, 21, 35, 55). In immunocompetent individuals, elevated liver enzymes accompany subclinical infection (54) as well as the natural disease mononucleosis (21, 33), in which hepatitis can be the presenting illness (18, 31). A better understanding of viral and host contributors to HCMV-induced liver damage and hepatitis in immunocompetent individuals will provide insights into potential therapeutic interventions as well as a foundation from which disease can be further studied in immunocompromised patients. HCMV exhibits strict species specificity (45), making the study of disease pathogenesis difficult. Murine CMV (MCMV) is a natural mouse pathogen that has unveiled principles of host immunity (3, 17, 71, 78), viral immune modulation (15, 34, 39, 53, 56, 61), and disease pathogenesis (23, 49) that have been translated to HCMV (25, 32, 34).

Like HCMV, MCMV causes a chronic, subclinical, systemic infection associated with elevated liver enzymes as well as histological evidence of hepatic inflammation and damage (20, 23, 27, 76). While lethal MCMV disease in immunocompetent BALB/c mice is attributed to liver damage culminating in a severe hepatitis within the first week of infection (69), factors contributing to this disease have not been characterized. Disease is prevented by administration of antiviral drugs, revealing a critical contribution of ongoing viral replication (81). Unlike other forms of hepatitis, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is dispensable for disease in BALB/c mice (70). Further elucidation of host and viral determinants of rapid hepatitis in immunocompetent mice may unveil mechanisms underlying liver damage during HCMV infection.

Inflammatory monocytes (IMs) are involved in MCMV hepatitis and disease pathogenesis. IMs are recruited by host (MCP1/CCR2) and viral (MCK2) chemokine signals (11, 53, 61). In C57BL/6 mice, IMs protect from lethal hepatitis by recruiting natural killer (NK) cells that control infection (23). In BALB/c mice, IMs restrict the antiviral CD8 T cell response, leading to a delay in viral clearance from peripheral organs (12). In this setting, IMs may also be responsible for immunopathology, as has been shown in other viral infections (16, 36).

During sublethal MCMV infection in BALB/c mice, CD8 T cells control viral replication in the liver as well as in most peripheral organs (77), while CD4 T cells control infection in salivary glands (29). Immunity depends on the collaborative efforts of cytokine and cytolytic activities of CD8 T cells (52, 77) to protect mice from lethal challenge (57). Immunodeficient mice lacking T cells exhibit a delay in time to death and less severe hepatitis compared to immunocompetent mice (50, 66, 75), raising the possibility that this arm of host defense may also contribute to disease. Given that CD8 T cell responses contribute to hepatitis in humans infected with hepatitis viruses A, B, and C and Epstein-Barr virus, in mouse models of hepatitis B virus infection (9, 14), and in mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) (83), the potential contribution of antiviral T cell responses to MCMV-induced lethal hepatitis needs to be evaluated.

The disease potential of MCMV depends on the source as well as strain of virus. Virus isolated from salivary glands is more virulent than virus propagated in cell culture or isolated from other organs (68). For this reason, and because natural viral transmission is mediated by saliva, pathogenesis studies have relied on salivary gland-derived virus (20, 23, 40, 49, 50, 65, 69). The Smith strain of MCMV was subjected to serial propagation through salivary glands of Swiss-Webster mice (51), resulting in the isolation of strain K181. K181 is more virulent than Smith (43) and can cause lethal hepatitis in BALB/c mice (69) but not in C57BL/6 mice (unpublished observation). When strain K181 was subjected to sequential passage in Swiss-Webster mice (68), strain v70 was isolated (although this strain, like K181, has often been called “Smith”) (48, 63). This strain was adopted for use in C57BL/6 mice based on its virulence characteristics (C. A. Biron and M. J. Selgrade, personal communication). Strain v70 has provided valuable insights into mechanisms of host response in C57BL/6 mice (22, 24, 48–50, 62, 63, 65) where control of virus is mediated by interferon (IFN) and IM recruitment of NK cells (23). In this strain, hepatitis results from poor control of viral infection and is associated with TNF production. In almost 20 years of study, v70 has not been directly compared to other MCMV strains or evaluated for disease potential in a common susceptible strain of mice such as BALB/c, in which CD8 T cells dominate host control and the potential for T cell-mediated pathology is greatest.

To identify host factors involved in lethal MCMV hepatitis, strain v70 was evaluated for its virulence potential in BALB/c mice using K181 as a reference. We show that BALB/c mice develop a rapid lethal hepatitis at a lower dose of v70 than K181, with a 10-fold difference in virulence potential. In examining host factors involved in disease, we identified a potent antiviral T cell response as a contributor to v70-induced hepatitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Six- to 12-week-old mice were used in all experiments. BALB/c and CBySmn.CB17-Prkdcscid/J (SCID) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. MCP1−/− CCR2−/− mice on a BALB/c background (47) and nonobese diabetic (NOD) SCID γc−/− (NSG) mice were bred and maintained in-house. Mice were group housed, maintained on a 12:12 h light-dark cycle, and fed rodent diet (LabDiet 5010; Purina Mills) ad libitum. All mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions by the Division of Animal Resources at Emory University or the Department of Comparative Medicine at Stanford University. Experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care and the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Viruses.

K181+ is a plaque-purified isolate of K181 that has been previously characterized (76). Salivary gland-propagated v70 was kindly provided by C. Biron (Brown University) (50). v70+ was generated by three rounds of plaque purification on 3T3-Swiss albino fibroblasts (ATCC CCL-92) cultured in Dulbecco's modified minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (DMEM). Tissue culture stocks of K181+ or v70+ were grown in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (ATCC CRL-1658). Viral stocks used in these studies were generated by inoculating BALB/c mice intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1 × 103 PFU of salivary gland-propagated v70 or 1 × 106 PFU of tissue culture-derived K181+ or v70+ as previously described (76). Organ sonicates (10% [wt/vol] in DMEM) were stored in single-use aliquots at −80°C.

Infections.

All experiments were carried out by i.p. inoculation using salivary gland-derived virus stocks. Mock infection was carried out using an equal volume of DMEM. Infected mice were monitored for development of disease by being weighed once daily and observed twice daily for signs of morbidity: piloerection, hunched posture, and lethargy. Imminent death was defined as loss of 20% initial body weight or development of severe lethargy (unresponsiveness to touch) established in a preliminary experiment using death as the endpoint. In experiments where mice were sacrificed at specific times, equal numbers of v70, v70+, or K181+ infected mice were evaluated at each time point.

Viral titers and serum chemistries.

For quantification of viral titers, organs were placed in 1 ml of DMEM and stored at −80°C until they were thawed and disrupted by sonication, and viral titers were evaluated by plaque assay on 3T3-Swiss Albino fibroblasts as previously described (38). Blood was obtained by cheek bleeds or cardiac puncture. Automated serum chemistries were evaluated using a VetScan VS2 machine (Abaxis) by the Division of Animal Resources at Emory University.

Histology.

Peripheral organs were isolated at the times indicated in the text below and figure legends. For histological analysis, organs were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The Division of Animal Resources and Yerkes Department of Pathology at Emory University performed all processing of histological samples following fixation. H&E-stained slides were blinded and evaluated by a veterinary pathologist (A.G.). Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded tissues using the anti-IE1 monoclonal antibody (Ab) CROMA 101 (kindly provided by S. Jonjic, University of Rijeka, Croatia) as previously described (26). Bound Ab was detected using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Labs), following manufacturer's instructions, and counterstained with Gill's hematoxylin solution number 2 (Electron Microscopy Services). Images of histology were acquired using an Olympus Q Color 3 camera and an Olympus BX43 microscope.

Fluorescently conjugated tetramer and Abs.

Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated H-2Ld-IE1168–174 tetramers were obtained from the NIH Tetramer Core Facility (Emory University). The Abs used were Ly6C fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (AL-21), IFN-γ FITC (XMG1.2), CD3 PE (17A2), IL-17 PE (TC11-18H10), CD4 peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-Cy5.5 (RM4-5), TNF PE-Cy7 (MP6-XT22), B220 PE-Cy7 (RA3-6B2), CD49b allophycocyanin (APC) (DX5), CD11b APC-Cy7 (M1/70), and CD3 Pacific blue (500A2), purchased from BD Biosciences; CD107a APC (1D4B) and CD8 APC-Cy7 (53-6.7), purchased from BioLegend; and CD45 PE-Texas red (30-F11), CD69 PE-Texas red (H1.2-F3), and CD8 Pacific orange (5H10), purchased from Invitrogen.

Characterization of leukocytes and flow cytometry.

Single cell suspensions were isolated from spleen and liver as previously described (30, 49). In all instances, 1 × 106 live cells, as evaluated by trypan blue (Cellgrow) exclusion, were prepared for flow cytometric detection of surface and intracellular antigens (Ag). For evaluation of T cell function, cells were incubated for 5 h at 37°C with 1 × 10−9 M IE1 peptide (JPT Peptide Technologies) (58) or 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma) and 500 ng/ml ionophore (Sigma) in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) and CD107a Ab. Prior to incubation with lineage-specific Ab, cells were incubated with 10% normal rat serum (Pel-Freez) and anti-mouse CD16/CD32 Ab (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen) to reduce nonspecific interactions. For detection of intracellular cytokines the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit from BD was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data were acquired using an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) maintained by the Emory University Flow Cytometry Core and analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star). For all samples, live cells were gated based on forward- and side-scatter properties followed by identification of leukocytes by CD45 expression. T cells were identified by expression of CD3 and further segregated into subsets based on expression of CD4 or CD8. All gates were established based on appropriate isotype and unstained controls.

Adoptive transfer and depletion.

Splenocytes used in adoptive transfers were prepared by mechanical disruption of the spleens of naïve BALB/c mice through a metal strainer, isolation via a Histopaque 1119 gradient (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and filtration through a 40-μm nylon screen. Viability was assessed on an aliquot of cells by trypan blue exclusion using a hemocytometer. A total of 4 × 107 cells in a total volume of 250 to 300 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were injected into tail veins of SCID mice. Mice were inoculated with MCMV 1 day after transfer of cells.

Rabbit anti-asialo-GM1 antisera (Wako) was administered in doses of 50 μl in 200 μl of PBS i.p. 1 day prior to infection, 1 day following infection, and every 3 days thereafter. CD4 (GK1.5; BioXcell) and CD8 (H35; kindly provided by A. Lukacher, Emory University) (73) Abs were used to deplete T cell subsets from BALB/c mice. For CD4 depletion, 500 μg of Ab was administered i.p. 1 day prior to and 1 day following infection. For CD8 depletion, 500 μg of Ab was administered i.p. on days −3, −1, and +1 relative to infection and maintained by weekly Ab injections. Prior to infection, blood was obtained from cheek bleeds in tubes containing lithium heparin (BD Biosciences), red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed using ammonium chloride solution (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM NaHCO3, and 1.0 mM Na2EDTA in H2O, pH 7.4), and engraftment or depletion was evaluated by flow cytometry. Ab depletion of NK, CD4, or CD8 cells achieved ≥95% depletion based on flow cytometry analysis.

Statistics.

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad). For comparison of survival curves, the Mantel-Cox test was employed. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for all other comparisons. In all comparisons, a P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Comparison of v70 and K181+ in BALB/c mice.

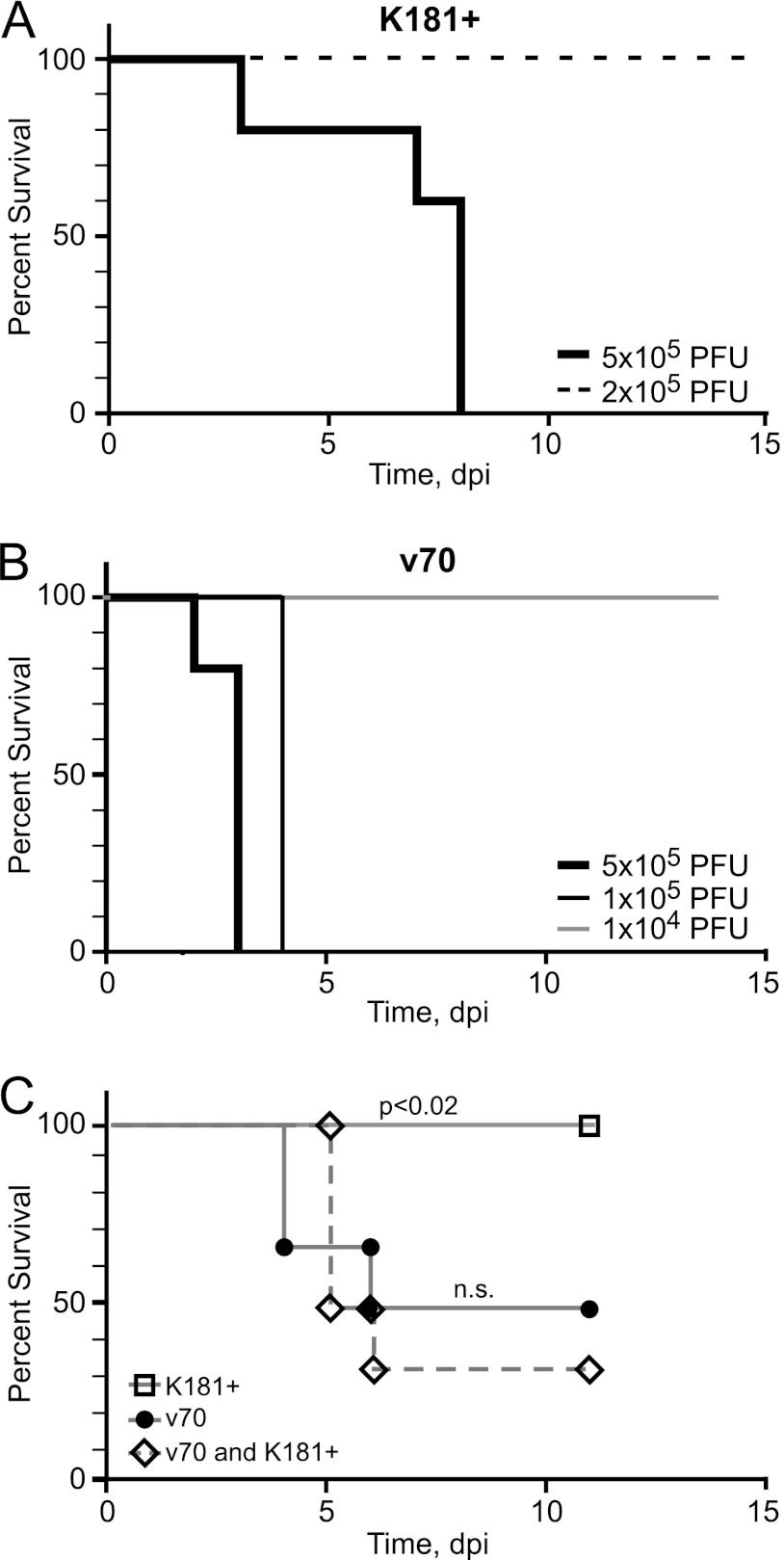

Many studies have employed salivary gland-propagated v70 (23, 48–50, 62–64) because it is a virulent strain of virus. To determine viral and host factors that contribute to MCMV disease pathogenesis, v70 was compared to K181+ (76), evaluating the endpoint of lethal infection in BALB/c mice. The criterion used to define imminent death was loss of >20% body weight or severe lethargy (see Materials and Methods). Mice inoculated with 5 × 105 PFU of K181+ uniformly died between days 3 and 8 (Fig. 1A), whereas mice survived a lower dose (2 × 105 PFU) of this virus. A dose of 1 × 105 PFU of v70 was uniformly lethal by 4 days postinfection (dpi) (Fig. 1B), and a dose of 5 × 104 PFU resulted in half the mice dying between days 4 and 6 (Fig. 1C). This, together with additional experiments whose results are not shown, allowed an estimation of the 50% lethal dose (LD50) for v70 between 2 × 104 and 5 × 104 PFU, whereas the LD50 for K181+ was estimated to be between 4 × 105 and 6 × 105 PFU. Both viruses exhibited a sharp cutoff for lethality (Fig. 1A), in line with expectations (66, 68, 69). These experiments established that v70 is highly virulent for BALB/c mice, showing an LD50 roughly 10-fold lower than that of K181+.

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots showing percent survival following infection with v70 or K181+ in BALB/c mice. (A and B) Infection with the indicated doses of K181+ (A) and v70 (B). (C) Infections with a dose of 5 × 104 PFU of K181+ alone or v70 alone or a combined dose of 5 × 104 PFU of K181+ and 5 × 104 PFU of v70. Mantel-Cox test was used to calculate P values by comparing singly infected mice to mice receiving the combined dose. n.s., nonsignificant (P > 0.05). Six or more mice were used in each group.

To determine whether differences in virulence were due to viral strain-specific factors, a coinfection experiment was performed (68). The pattern of lethality in BALB/c mice inoculated with 5 × 104 PFU of K181+ or v70 alone was compared to that in mice coinfected with 5 × 104 PFU of each strain given together (Fig. 1C). Coinfection resulted in death of 60% of the mice by day 6, similar to results obtained with v70 alone but significantly different from those of single infection with K181+, where all mice survived. This pattern demonstrates that K181+ does not express a protective factor and is consistent with v70 encoding a dominant virulence factor contributing to lethal disease.

Disease severity and viral replication.

Strain-specific replication potential in vivo has been associated with the virulence of strain K181 compared to Smith (43). To determine whether v70-associated virulence was associated with greater replication potential, we followed disease patterns and assessed viral titers in peripheral organs after inoculation with 1 × 105 PFU of v70 or K181+. This was predicted to be a lethal v70 dose but sublethal for K181+ (Fig. 1A and B). Mice inoculated with either v70 or K181+ all showed signs of illness (weight loss and changes in appearance) beginning on day 2 and continuing on day 3 (Fig. 2A and data not shown). Important differences in disease were observed on days 4 and 5, when mice infected with K181+ stabilized as mice infected with v70 continued to decline. By day 5, 8 out of 10 mice infected with v70 had died, in contrast to those infected with K181+, which all survived. At no point did any of the infected mice develop neurological symptoms (photophobia and ataxia), consistent with previous studies (69). Viral titers were indistinguishable in organs assayed at day 3, but thereafter, they followed a pattern implicating the liver as a target of disease. In the liver, viral titers declined more gradually during v70 infection than during K181+ infection, such that v70 was sustained in this organ at a modestly higher level as disease progressed and mice died (Fig. 2B, top). Viral titers in other organs (spleen, lung, and kidney) followed organ-specific patterns that did not correlate with disease outcome because v70 and K181+ were indistinguishable (Fig. 2B, bottom, and data not shown). Although infections resulting in lethal and sublethal disease exhibited similar patterns of viral replication overall, the sustained v70 titers in the liver suggest a relationship to disease and death.

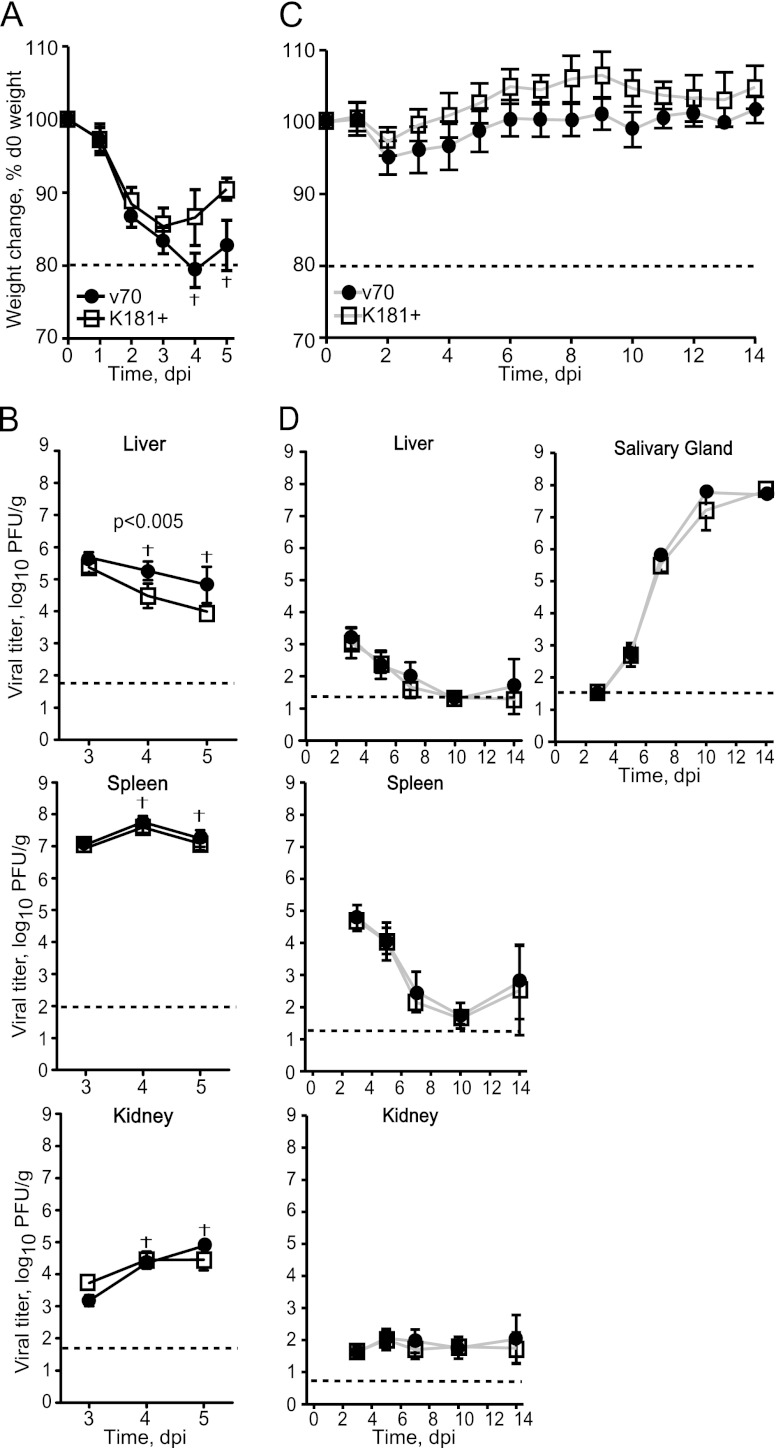

Fig 2.

Disease and viral replication patterns at high and low doses. (A) Weight loss in mice inoculated with 1 × 105 PFU of v70 or K181+ expressed as percentage of weight prior to infection (d0). Shown is the mean ± range. The dotted line indicates 20% weight loss. Seven v70-infected mice and one v70-infected mouse died at days 4 and 5 postinfection, respectively. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Viral titers in indicated organs from mice in panel A. Five mice from each group were sampled at day 3, seven at day 4, and three at day 5. Symbols represent means of log10 of viral titers ± SDs. Dashed line indicates limit of detection. (C) Weight loss in mice inoculated with 1 × 104 PFU of v70 or K181+ as depicted in panel A. Data represents a single experiment. (D) Viral titers in indicated organs from mice in panel C. Five mice were sampled from each group at the indicated times. Results are graphed as in panel B. The dagger indicates a time when v70-infected mice met euthanasia criteria. P value determined by Mann-Whitney U test.

To further evaluate the replication potential of these viral strains, we compared virus titers at a dose that was sublethal for v70 as well as K181+. After inoculation with 1 × 104 PFU of either virus strain, weight loss (Fig. 2C) and appearance (data not shown) were similar and did not change as dramatically as at the high dose (compare to Fig. 2A). Overall, peak titers in liver and spleen occurred over the same time frame (by 3 dpi) but remained orders of magnitude lower in mice infected with 1 × 104 PFU (Fig. 2D, top left and middle) than in animals receiving 1 × 105 PFU (Fig. 2B, top), as expected from earlier evaluations (67). At the low dose, both v70 and K181+ titers declined in the liver, with identical patterns by day 10 (Fig. 2D, top left). Consistent with high-dose data, replication followed similar organ-specific patterns in spleen, kidneys, and lungs (Fig. 2D, bottom, and data not shown). The patterns of replication in salivary glands, the target of viral dissemination, were also identical, peaking near 108 PFU/g of tissue at 10 and 14 dpi (Fig. 2D, right). Overall patterns of viral replication and clearance were remarkably parallel, suggesting that the disease process was responsible for sustaining viral levels in the liver at the high dose of v70.

Hepatitis underlies lethal disease.

We next followed the development of disease in relation to serum chemistries and pathology. Again, a dose of 1 × 105 PFU of v70 or K181+ was employed to induce a lethal (v70) or sublethal (K181+) infection. This dose resulted in a similar pattern of weight loss through 3 dpi (Fig. 3A), with weight loss in v70 infection progressing through day 4, when two mice died, and day 5, when remaining mice succumbed. In contrast, all mice infected with K181+ survived, with mice showing signs of recovery at days 4 and 5. Blood was analyzed for serum chemistries and samples of liver, adrenal gland, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, pancreas, and spleen were evaluated daily for histopathological damage from days 2 through 5. These organs were chosen as they all become productively infected within the first 5 days of infection with MCMV (27, 69). Samples were collected from randomly selected mice at all time points except for days 4 and 5, when mice that had died were included.

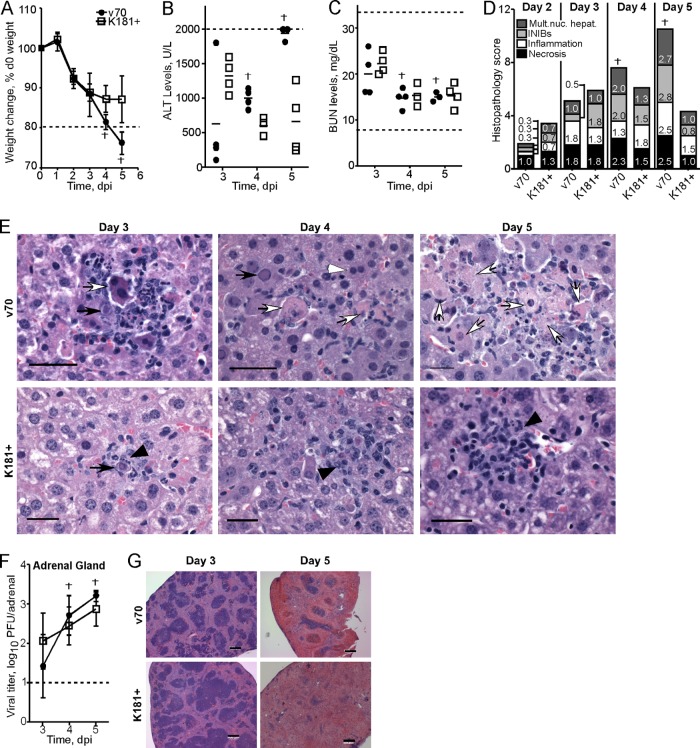

Fig 3.

Evaluation of pathological changes during lethal and nonlethal infections. BALB/c mice were inoculated with 1 × 105 PFU of v70 or K181+. (A) Weight loss as depicted in Fig. 2A, with dashed line indicating 20% weight loss from day 0 (d0). (B and C) Evaluation of serum chemistries from mice in panel A. (B) Serum ALT levels at the indicated times; the upper limit of detection for this assay was 2,000 U/liter, indicated by dashed line. On day 5, two v70-infected samples were above the upper limit of detection. (C) Serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels at the indicated times. Dashed lines indicate normal BUN range. (D and E) Evaluation of hepatic histopathology from mice in panel A. (D) Scores of cumulative pathology on indicated days postinfection for multinucleated hepatocytes, intranuclear inclusion bodies (INIBs), inflammation, and necrosis using the following scoring system: 0, normal (no pathology); 1, mild, i.e., 1 to 3 abnormal areas; 2, moderate, i.e., 3 to 5 abnormal areas; and 3, severe, i.e., >5 abnormal areas. Prior to evaluation, histological samples were blinded. Bars correspond to the mean score for each parameter. The height of each bar represents the total histological score (out of 12) that incorporates each individual pathology parameter. Three mice infected with each virus were evaluated at day 2, and four mice for each infection group were evaluated at all other times. (E) Representative images of liver histology at indicated time points from samples used to assemble panel D. White arrowheads indicate multinucleated hepatocytes, black arrows INIBs, black arrowheads inflammation, and white arrows necrosis. Scale bars indicate 250 μm. Images are representative of two independent experiments. (F) Viral titers in the adrenal gland from mice in panel A are depicted at indicated time points as in Fig. 2C. The dagger indicates a time point when v70-infected mice died. (G) Representative images of splenic pathology at indicated time points from mice in panel A. Scale bars indicate 200 μm.

At day 3, serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels were higher in sublethally infected than in lethally infected mice (Fig. 3B). ALT levels subsequently decreased during sublethal infection and stabilized by day 5. Over this time, ALT levels increased progressively in lethally infected mice, ultimately rising above peak levels observed in mice that survived. ALT levels may increase due to liver or kidney dysfunction. Kidney function was not altered based on serum BUN and creatinine levels (Fig. 3C and data not shown), indicating that elevated ALT reflected liver damage. The falling pattern of ALT during sublethal infection was consistent with recovery, whereas the rising pattern in lethally infected mice was associated with disease and death.

To directly evaluate hepatic pathology, liver sections were blinded and scored by a veterinary pathologist (A.G.). Virus-associated hepatic cytopathology was assessed by the presence of intranuclear inclusion bodies and multinucleated hepatocytes. Sublethally infected mice reached peak scores for necrosis and inflammation at day 3 (Fig. 3D and E). The scores in lethally infected mice were parallel through day 3 but continued to rise at days 4 and 5, when mice succumbed. While less histopathological damage was evident at day 2 in lethally infected mice and ALT levels were lower at day 3, this delay was not associated with v70-induced disease, because hepatic viral titers were identical in lethally and sublethally infected mice at these times (Fig. 2B and data not shown). Taken together with hepatic viral titers (Fig. 2B) and lethality (Fig. 1 and 3A), liver pathology at days 4 to 5 correlated with disease outcome.

In contrast to the liver, there were no histopathological differences in other organs from sublethally or lethally infected mice. Adrenal glands had similar cytopathology (Table 1) and viral titers (Fig. 3F) as well as mild to moderate levels of inflammation and necrosis at days 4 and 5 (Table 1). Likewise, the small intestine showed mild inflammation that was maintained for the 5-day experiment, while the stomach and colon appeared normal (data not shown). In pancreatic sections, little pathology was observed and serum amylase levels, used as an indicator of pancreatic function, remained normal (data not shown). Coincident with the high levels of virus (Fig. 2B, middle), spleens showed gross pathology associated with firm, dark surface areas that developed in both sublethally and lethally infected mice independent of virus strain. These were first apparent on day 3 and increased in size through day 5, when the entire organ appeared to be necrotic (data not shown). Gross evidence of necrosis was confirmed by histological evaluation and was associated with moderate to severe lymphoid depletion and necrosis (Fig. 3G and Table 1), similar to an earlier report (41). Thus, splenic damage during MCMV infection is severe but does not correlate with disease outcome.

Table 1.

Pathology scores in adrenal glands and spleen

| Tissue | Virusa | dpi | INIBb | Inflammation | Necrosis | Lymphoid depletion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenal | K181+ | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| v70 | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| K181+ | 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| v70 | 3 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | ||

| K181+ | 4 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 | ||

| v70 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 | ||

| K181+ | 5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ||

| v70 | 5 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.7 | ||

| Spleen | K181+ | 2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| v70 | 2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| K181+ | 3 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| v70 | 3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| K181+ | 4 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.3 | |

| v70 | 4 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | |

| K181+ | 5 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 2.5 | |

| v70 | 5 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 2.9 |

BALB/c mice were inoculated with 1 × 105 PFU of indicated virus.

Values represent the average pathology score for each parameter in organ sections from three to four mice per virus at each time point. Prior to evaluation, samples were blinded and scores determined as in Fig. 3.

The histological data agree with earlier reports that concluded that hepatitis underlies lethal MCMV infection in susceptible strains of mice (40, 69) and identify a critical period from days 3 to 5 when this disease develops, potentially setting the stage for contributions of the host immune response to hepatic damage.

IMs do not influence lethal disease in BALB/c mice.

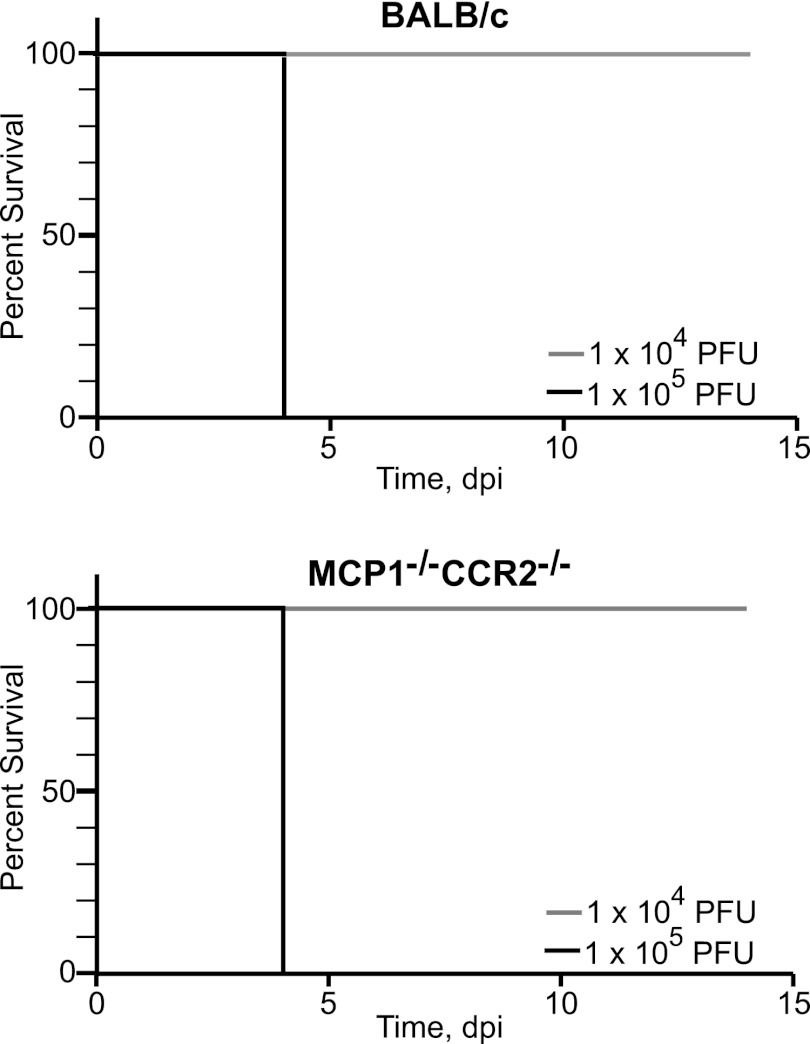

In evaluating the contribution of host responses to severe disease, we initially focused on IMs, known mediators of pathogenesis in MCMV and other viral infections (12, 16, 23, 36). Mice lacking MCP1 and/or CCR2 are impaired in their ability to recruit IMs from bone marrow (11, 47). BALB/c and MCP1−/− CCR2−/− mice exhibited identical susceptibilities to 1 × 105 and 1 × 104 PFU of v70 (Fig. 4). Compromising CCR2 signaling and the subsequent mobilization of IMs from bone marrow did not increase susceptibility of BALB/c mice to lethal disease, consistent with earlier work (47). This result contrasts the protective role that IMs play in C57BL/6 mice (23), in which these cells recruit NK cells to the liver, controlling viral infection and preventing disease. While IMs protect from lethal hepatitis in C57BL/6 mice, they do not contribute to protection from or promotion of disease in BALB/c mice.

Fig 4.

Kaplan-Meier plots showing the percent survival of BALB/c and MCP1−/− CCR2−/− mice infected with v70. Mice were inoculated with the indicated doses of v70. Three mice were administered the high dose and five the low dose.

Adaptive immune response contributes to disease.

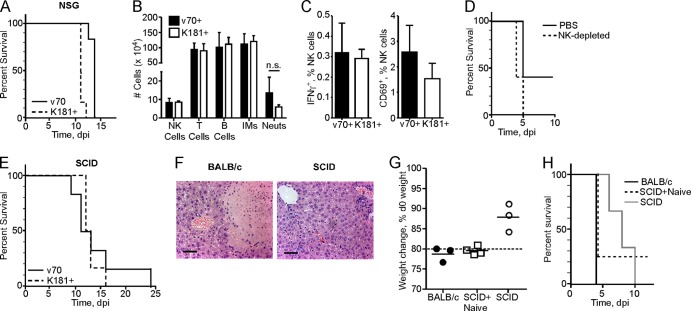

Having ruled out IMs, we next evaluated the contribution of cytotoxic lymphocytes to disease progression by inoculating NSG mice. NSG mice are on the BALB/c-related NOD background, harbor the severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mutation, and lack the common gamma chain of the interleukin 2 (IL-2) receptor, resulting in a lack of functional T, B, and NK cells and impaired cytokine signaling. When NSG mice were inoculated with 1 × 105 PFU of v70 or K181+, lethal disease developed between days 9 and 10 (Fig. 5A). A 6-day delay in time to disease was evident in these immunodeficient mice compared to immunocompetent BALB/c mice inoculated with the same dose of v70 (Fig. 1B), indicating a potential contribution of immune components to rapid hepatitis. Based on this pattern of delayed death in immunodeficient mice, we set out to identify the components of the immune response that predispose to rapid and severe disease in immunocompetent mice.

Fig 5.

Evaluation of NK cells and adaptive immunity in disease. Mice were inoculated with 1 × 105 PFU of v70, v70+, or K181+. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot showing percent survival of NSG mice inoculated with v70 or K181+ (six mice per group). (B) Total number of indicated hepatic leukocytes isolated at 5 dpi from BALB/c mice. Using flow cytometry, subsets were defined as follows: NK cells, CD3− CD49d+; T cells, CD3+ CD49d−; B cells, CD19+; IMs, CD3− Ly6Chi CD11b+; neutrophils (Neuts), CD3− Ly6CInt CD11b+. n.s., nonsignificant (P > 0.05) by Mann-Whitney U test. (C) Frequency of IFN-γ+ or CD69+ NK cells. NK cells identified in panel B were evaluated directly ex vivo for intracellular IFN-γ or surface expression of CD69. Bars in panels B and C indicate means ± SDs of five mice in each group. (D) Kaplan-Meier plot showing percent survival of BALB/c mice following administration of anti-asialo-GM1 or PBS control prior to inoculation with v70 (five mice per group). (E) Kaplan-Meier plot showing percent survival of SCID mice inoculated with v70 or K181+ (six mice per group). (F) H&E-stained liver sections at 4 dpi from BALB/c and SCID mice inoculated with v70. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. (G) Weight loss at day 4 following v70 inoculation of BALB/c, SCID mice that received 4 × 107 bulk splenocytes from naïve BALB/c mice 1 day prior to infection, or unmanipulated SCID mice. Line indicates mean; dashed line indicates 20% weight loss from day 0 (d0). (H) Kaplan-Meier plot showing percent survival of mice in panel E. All data are representative of two or three independent experiments except panels C and D, in which data for a single experiment are shown.

NK, T, and B cell levels were assessed in the liver via flow cytometry at day 5 in BALB/c mice inoculated with a lethal dose of a plaque-purified derivative of v70, called v70+, or a sublethal dose of K181+. At this time point, mice infected with v70+ were dying, while those infected with K181+ were recovering (data not shown). There were no differences in total numbers or proportion of any leukocyte population in the liver (Fig. 5B and data not shown). We determined whether NK cell activation was altered during lethal and sublethal infection. No differences were observed in either of the NK cell activation markers IFN-γ and CD69 (Fig. 5C). Additionally, depletion of NK cells using anti-asialo-GM1 did not affect v70-induced disease in BALB/c mice (Fig. 5D). While critical for controlling infection as well as disease in C57BL/6 mice (8, 23), our data reinforce the lack of NK cell contribution to either host defense or disease pathogenesis in BALB/c mice.

The contribution of the adaptive immune response to disease was assessed by inoculating SCID mice with 1 × 105 PFU of v70 or K181+. These mice are on the BALB/c background and lack functional T and B cells due to the SCID mutation. SCID mice died in a pattern similar to that of NSG mice (Fig. 5E). Severe hepatitis observed in BALB/c mice infected with v70 was absent in SCID mice (Fig. 5F). v70-infected BALB/c mice also showed greater weight loss at day 4 (Fig. 5G). Viral titers at day 4 in BALB/c and SCID mice were identical, indicating that viral replication is not the primary driver of hepatitis (data not shown). These results implicate the adaptive T and B cell responses in the rapid disease affecting immunocompetent mice.

To further investigate the contribution of immune cells to disease, we attempted to isolate splenocytes from BALB/c mice infected for 4 days with a lethal dose of v70; however, splenic necrosis (Fig. 3G and Table 1) prevented isolation of sufficient cells (data not shown). We then tested naïve cells, transferring 4 × 107 BALB/c splenocytes into SCID mice 1 day prior to infection with 1 × 105 PFU of v70. Mice that received splenocytes lost significantly more weight than unmanipulated SCID mice in a pattern similar to that for BALB/c mice (Fig. 5G). Three out of four SCID mice that received splenocytes died at day 4, similar to BALB/c mice (Fig. 5H), whereas control SCID mice succumbed between days 6 and 10. These data showed that BALB/c splenocytes contained a cell population that conferred disease on SCID mice. One SCID mouse that received splenocytes survived through day 12, reminiscent of the occasional survival of BALB/c mice subjected to a lethal dose of v70 (Fig. 2A). As expected, splenocytes from sublethally infected BALB/c mice protected SCID mice from a lethal challenge 1 day after transfer (data not shown). Thus, the response mounted by naïve splenocytes contributes to disease or provides protection, depending on the dose of virus given.

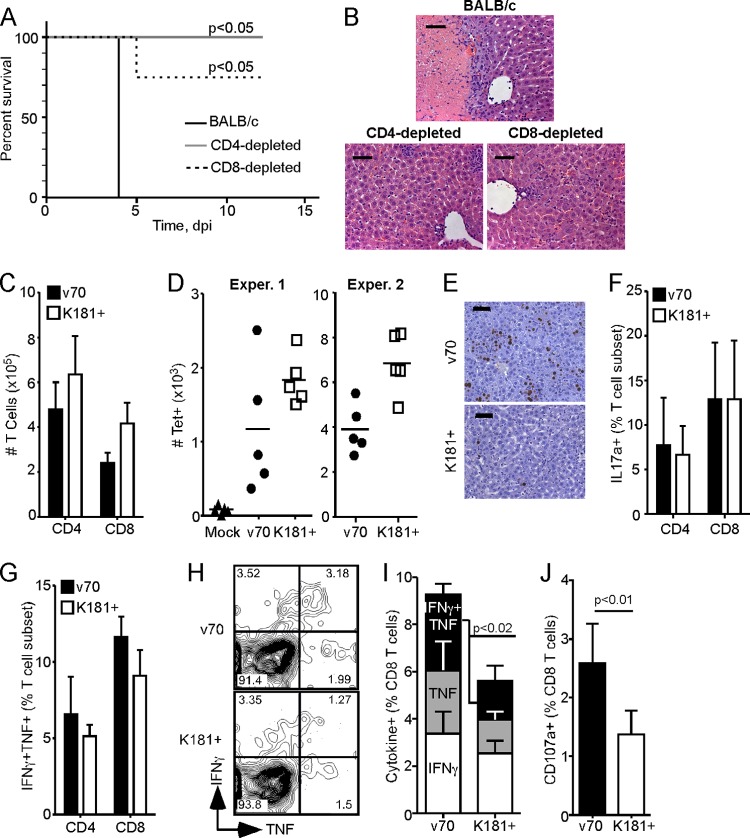

Disease is dependent on T cells.

We next sought to investigate whether an adaptive immune cell population was associated with rapid disease in immunocompetent mice. Given that SCID and T cell-deficient athymic nu/nu mice show similar delayed patterns of death (75), we focused on T cells by depleting CD4 or CD8 cells from BALB/c mice followed by a lethal dose of v70. T cell-depleted mice exhibited less disease than control BALB/c mice, with depleted mice surviving the experiment (aside from one CD8-depleted mouse that died at day 5) while control mice succumbed (Fig. 6A). Histological analysis at 4 dpi revealed the expected necrosis in immunocompetent mice that was uniformly absent from livers of CD4- or CD8-depleted mice (Fig. 6B). Thus, lethal hepatitis in immunocompetent mice required the combined activity of CD4 and CD8 T cell subsets.

Fig 6.

Evaluation of T cells in lethal disease. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot showing percent survival of BALB/c mice depleted of CD4 or CD8 cells (4 mice per group) or left untreated (BALB/c; 3 mice) and inoculated with 1 × 105 PFU of v70. Mantel-Cox test was used to calculate P value by comparing depleted mice to untreated BALB/c mice. (B) Representative H&E-stained liver sections at 4 dpi from mice treated as in panel A. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. (C to J) Livers were harvested at 4 dpi from BALB/c mice inoculated with 1 × 105 PFU of v70 or K181+. Bar graphs indicate means of five mice per group ± SDs. (C) Total number of hepatic CD4 and CD8 T cells isolated. (D) Total number of hepatic IE1-specific (Tet+) CD8 T cells. Line indicates mean. Two independent experiments are shown. (E) IE1 and hematoxylin-stained liver sections. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. (F) Frequency of hepatic CD4 or CD8 T cells producing IL-17a after a 5-h stimulation with PMA and ionophore. (G) Frequency of hepatic CD4 and CD8 T cells producing both IFN-γ and TNF after a 5-h stimulation with PMA and ionophore. (H) Flow cytometric plots of CD8 T cells assessed for IFN-γ and TNF production following IE1 peptide stimulation. (I) Frequency of CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ, TNF, or both cytokines following IE1 peptide stimulation. (J) Frequency of CD107a+ CD8 T cells during IE1 peptide stimulation. P values in panels I and J were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. All data are representative of two independent experiments.

T cell response parameters were evaluated in livers of BALB/c mice, comparing responses generated during lethal (v70) and sublethal (K181+) infections. At day 4, similar numbers of hepatic CD4 T cells were recovered from both groups of animals (Fig. 6C). There was a trend of fewer total CD8 T cells and fewer CD8 T cells recognizing the immunodominant viral IE1 epitope (as measured by tetramer staining) recovered from lethally infected livers (Fig. 6C and D), although the frequency of IE1-specific CD8 T cells was the same in both infections (data not shown). When liver sections from infected mice were stained for IE1 antigen, there were greater numbers of viral Ag-positive cells in lethally than in sublethally infected mice (Fig. 6E), consistent with the pattern of viral titers (Fig. 2B, top) as well as the trend toward fewer CD8 T cells (Fig. 6C and D). We next compared the quality of hepatic T cell responses in lethally and sublethally infected mice, employing PMA and ionophore stimulation to activate T cells. We did not observe any difference in IL-17-producing T cells (Fig. 6F), ruling out Th17 cells as major contributors to lethal hepatitis (82) in the context of MCMV infection. There was a trend of increased bifunctional T cells, secreting both IFN-γ and TNF, within the CD4 and CD8 T cell populations from lethally infected mice (Fig. 6G). Results similar to those obtained with PMA and ionophore were also obtained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 Ab costimulation (data not shown). Extending this analysis to include Ag-specific CD8 T cell responses, we employed stimulation with IE1 peptide (58) and looked at functionality. Lethally infected mice generated a significantly higher frequency of bifunctional CD8 T cells (Fig. 6H and I). These cells also had increased surface levels of the degranulation marker CD107a (5) (Fig. 6J), consistent with increased effector phenotype. Overall, patterns of increased hepatitis and disease correlated with potency and functionality of hepatic CD8 T cells. Thus, the quality, rather than the quantity, of the T cell response correlated with MCMV-associated hepatic disease.

DISCUSSION

To more fully understand host factors that contribute to disease, we investigated virus-induced pathology and identified differences in host response parameters correlating with disease potential. By employing a highly virulent MCMV strain, v70, we characterized lethal infection as follows: (i) hepatitis underlies the rapid and severe disease that kills immunocompetent mice, (ii) both CD4 and CD8 T cells contribute to disease, and (iii) potent antiviral CD8 T cells normally associated with control of infection predominate in the disease setting. It is difficult to dismiss the sustained viral levels in the livers of lethally infected mice, as these levels may contribute to or be a result of disease pathogenesis. Indeed, it is possible that the recruitment of fewer CD8 T cells to the liver during lethal infections directly leads to the elevated titers. However, the strikingly parallel replication and dissemination patterns observed when sublethal doses of v70 and K181+ were compared indicate that differences in replication potential are not at the root of disease pathogenesis. These studies establish that the increased virulence of v70, which has been utilized almost exclusively in virus-resistant C57BL/6 mice (13, 23, 48–50, 62–65), applies to pathogenesis in virus-susceptible BALB/c mice. In these mice, T cells can control infection as well as mediate immunopathology that seems to be in a delicate balance with viral factors during the response to infection.

The rapid hepatitis observed in BALB/c mice is reminiscent of earlier observations of hepatic dysfunction during lethal MCMV infection (69). The liver, rather than other organs such as the adrenal glands, kidneys, or GI tract, is the target organ underlying disease. Between days 3 and 4, factors elaborated by the more virulent v70 strain tilt the balance toward progression to hepatitis. These virulence factors interface with the T cell response as a partner in disease pathogenesis. Following i.p. inoculation, both liver and spleen are seeded within hours (27), and both are damaged in lethally infected mice. Hepatic damage leads to life-threatening illness, whereas splenic damage is tolerated, even when severe (41). Our observations suggest that lethal doses of MCMV result in the dual insult of viral infection and pathological antiviral T cell responses that together result in lethal hepatitis.

The finding that IMs do not contribute to disease susceptibility in BALB/c mice contrasts observations in C57BL/6 mice, in which this axis contributes to NK cell recruitment that protects from lethal hepatitis (23). Unlike BALB/c mice, C57BL/6 mice express Ly49H, an activating NK cell receptor that recognizes virus-encoded m157, a major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) homologue that drives an overwhelming NK response (2, 72). When m157 or Ly49H is eliminated, MCMV infection in C57BL/6 mice resembles that in BALB/c mice, with viral control mediated by a robust CD8 T cell response rather than NK cells (7, 44). Our understanding of disease pathogenesis in BALB/c mice therefore opens the door to future mechanistic studies of lethal T cell-dependent hepatitis utilizing existing mutant strains of mice on the C57BL/6 background in combination with an m157-deficient virus.

The contribution of T cells to disease in BALB/c mice is consistent with the delayed susceptibility of both NSG and SCID mice and is reminiscent of the behavior in T cell-deficient nu/nu mice (75). Like hepatitis viruses A, B, and C, as well as LCMV (9, 14, 83), MCMV induces disease that is dominated by T cell-mediated pathology rather than direct damage resulting from virus replication. Studies in these various systems have identified a contribution of virus-specific CD8 T cells, but no role for CD4 T cell responses, in the disease susceptibility of immunocompetent hosts. In our study, depletion of CD4 or CD8 cells suggests that both T cell subsets work together to produce the conditions leading to lethal hepatitis. While CD4 T cells are unlikely to directly kill hepatocytes, these cells produce a wide range of cytokines that influence the immune response, including IL-17, a cytokine that has been associated with acute hepatitis by facilitating the recruitment of neutrophils (82). We did not observe any difference in IL-17 production by CD4 T cells or neutrophil recruitment during lethal or sublethal infection (Fig. 5B), suggesting that this axis does not drive lethal MCMV hepatitis. Other CD4-derived cytokines can influence hepatitis via direct effects on hepatocytes (such as IFN-γ and TNF) and modulation of CD8 T cells by supporting (IL-2 and IFN-γ) or inhibiting (IL-10 and IL-4) survival and antiviral activity. Given that a stronger CD8 T cell response is associated with hepatitis, the CD4 T cell response may help increase potency of the CD8 T cells responding to lethal infection, similar to the role CD4 T cells play in maintaining CD8 effector memory in the periphery (74). The Th1 cytokines, IL-2 and IFN-γ, and proinflammatory TNF contribute to the help CD4 T cells provide CD8 T cells. Although the frequency of IL-2-, IFN-γ-, or TNF-producing CD4 T cells did not vary during lethal compared to sublethal infection (data not shown), differences may emerge from further studies of the Ag-specific CD4 response.

In a pattern analogous to that in other viral hepatitides, virus-specific CD8 T cell responses appear to be involved in lethal MCMV hepatitis. Significant differences in hepatic CD8 T cell quality in mice infected with lethal or sublethal doses were observed only after coculture with viral Ag and not nonspecific stimulation. Broadly speaking, there are two ways that CD8 T cells may mediate protection or pathology: direct lysis of infected cells and indirect damage via secreted cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF. Studies with hepatitis B virus, in particular, distinguish between these two capacities, with cytotoxicity associated with disease pathology and cytokines associated with protection (9). In LCMV-induced hepatitis, IFN-γ, in particular, drives cytotoxic capacity in CD8 T cells, contributing to both protection and pathology (4, 60, 79, 80). Experiments distinguishing a protective CD8 T cell response from a pathological one have not been performed. By utilizing two strains of MCMV with different disease potentials, we directly compared a protective CD8 T cell response (mounted against K181+) to a pathological response (mounted against v70). Interestingly, we found that the pathological CD8 T cells were characterized by increased cytotoxic potential and bifunctionality, characteristics that are typically associated with protection (80). Thus, it appears that a more intense response is not necessarily better and can lead to pathology and even death. Further studies on the quality of infected cells and the T cells that respond to lethal and sublethal infections should provide insights into these different disease outcomes.

The presence of functional virus-specific CD8 T cells in the liver at 4 dpi was unexpected. In mouse models, such T cell responses are typically not detected in nonlymphoid organs prior to 5 dpi, and the responses peak between days 7 and 10 (46, 80). Studies have historically focused on peak responses, which may follow rather than precede disease. Here, an antiviral T cell response at day 4 seemed to be the crucial determinant in the outcome of infection. T cell correlates of protection and pathology may differ depending on the time postinfection, as a CD8 T cell response, considered to be more protective at day 7 (80), is associated with immunopathology at day 4. Further study of these early T cell responses in MCMV and other viral infections will likely lead to insights into disease pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions.

While our study focused on host contributions to disease, the comparison between v70 and K181+ show that viral factors are also important in disease pathogenesis. The dominance of v70 during coinfection suggests that v70 encodes a virulence determinant contributing to disease. Once v70 stock virus is fully characterized, future sequence analysis will seek to identify the viral factor(s) responsible for virulence differences. Our findings regarding the involvement of the host T cell response in lethal v70 infection leads to the expectation that the virulence factor likely targets either CD4 or CD8 T cells. MCMV is known to possess several genes that enhance or restrict the CD8 T cell response such as m04, m06, m129-m131 (MCK-2), and m152 (6, 12, 15). While less well understood, MCMV also modulates CD4 T cell responses through mechanisms interfering with MHC-II expression (19, 59) and T cell activation via downregulation of costimulatory molecules by m138 and m155 (37, 42). Any T cell modulation that occurs in v70-infected BALB/c mice appears subtle, as viral titers remain very similar to K181+ at low or high doses. Viral regulation of the T cell response may be limited to the liver, as sustained hepatic titers at high doses of v70 were the only difference observed. Future studies focused on identification of v70 virulence determinants will enable better understanding of the mechanisms through which v70 induces a potent pathological CD8 T cell response.

Given that identification of protective anti-MCMV CD8 T cell responses has been followed by the recognition that anti-HCMV responses are similarly protective (32), the results revealed here suggest the possibility that anti-HCMV T cell responses may mediate pathology in some settings, such as the liver dysfunction that accompanies infection (21, 45). Studies that dissect the contribution of anti-HCMV specific CD4 or CD8 T cell responses to disease are needed. Given that T cells are clearly involved in hepatitis during MCMV infection, evaluation of T cell function in immunocompetent patients with HCMV hepatitis would be especially informative.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Grace Wynn, William Kaiser, Linda Roback, Eileen Breding, Evan Dessausa, and the Yerkes Histopathology Core for providing technical assistance. We extend thanks to Mandy Ford, James Zimring, David Weiss, Samuel Speck, Ifor Williams, and members of the Mocarski laboratory for valuable discussions. We thank Richard Dix for critical reading of the manuscript and Christine Biron, Stipan Jonjic, Aron Lukacher, and Rafi Ahmed for their generosity in providing reagents.

This work was supported in part by the Flow Core of the Emory University School of Medicine, National Institutes of Health grants RO1 AI030363 and AI020211 (to E.S.M.), T32 GM008169, and an ARCS Fellowship (to D.L.-R.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Aberg F, Mäkisalo H, Höckerstedt K, Isoniemi H. 2011. Infectious complications more than 1 year after liver transplantation: a 3-decade nationwide experience. Am. J. Transplant. 11:287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arase H, Mocarski ES, Campbell AE, Hill AB, Lanier LL. 2002. Direct recognition of cytomegalovirus by activating and inhibitory NK cell receptors. Science 296:1323–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnoult D, Skaletskaya A, Estaquier J, Dufour C, Goldmacher VS. 2008. The murine cytomegalovirus cell death suppressor m38.5 binds Bax and blocks Bax-mediated mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. Apoptosis 13:1100–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balkow S, et al. 2001. Concerted action of the FasL/Fas and perforin/granzyme A and B pathways is mandatory for the development of early viral hepatitis but not for recovery from viral infection. J. Virol. 75:8781–8791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Betts MR, et al. 2003. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J. Immunol. Methods 281:65–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Böhm V, et al. 2008. The immune evasion paradox: immunoevasins of murine cytomegalovirus enhance priming of CD8 T cells by preventing negative feedback regulation. J. Virol. 82:11637–11650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bubić I, et al. 2004. Gain of virulence caused by loss of a gene in murine cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 78:7536–7544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bukowski JF, Woda BA, Habu S, Okumura K, Welsh RM. 1983. Natural killer cell depletion enhances virus synthesis and virus-induced hepatitis in vivo. J. Immunol. 131:1531–1538 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chisari FV, Isogawa M, Wieland SF. 2010. Pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. Pathol. Biol. 58:258–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Costa FA, et al. 2011. Simultaneous monitoring of CMV and human herpesvirus 6 infections and diseases in liver transplant patients: one-year follow-up. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 66:949–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crane MJ, Hokeness-Antonelli KL, Salazar-Mather T. 2009. Regulation of inflammatory monocyte/macrophage recruitment from the bone marrow during murine cytomegalovirus infection: role for type I interferons in localized induction of CCR2 ligands. J. Immunol. 183:2810–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daley-Bauer LP, Wynn GM, Mocarski ES. 2012. Cytomegalovirus impairs antiviral CD8+ T cell immunity by recruiting inflammatory monocytes. Immunity 37:122–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dalod M, et al. 2003. Dendritic cell responses to early murine cytomegalovirus infection: subset functional specialization and differential regulation by interferon alpha/beta. J. Exp. Med. 197:885–898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dienes H-P, Drebber U. 2010. Pathology of immune-mediated liver injury. Dig. Dis. 28:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doom CM, Hill AB. 2008. MHC class I immune evasion in MCMV infection. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197:191–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Getts DR, et al. 2008. Ly6c+ “inflammatory monocytes” are microglial precursors recruited in a pathogenic manner in West Nile virus encephalitis. J. Exp. Med. 205:2319–2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goldmacher VS, et al. 1999. A cytomegalovirus-encoded mitochondria-localized inhibitor of apoptosis structurally unrelated to Bcl-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:12536–12541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanshaw JB, Betts RF, Simon G, Boynton RC. 1965. Acquired cytomegalovirus infection: association with hepatomegaly and abnormal liver-function tests. N. Engl. J. Med. 272:602–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heise MT, Connick M, Virgin HW. 1998. Murine cytomegalovirus inhibits interferon gamma-induced antigen presentation to CD4 T cells by macrophages via regulation of expression of major histocompatibility complex class II-associated genes. J. Exp. Med. 187:1037–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henson D, Smith RD, Gehrke J. 1966. Non-fatal mouse cytomegalovirus hepatitis. Combined morphologic, virologic and immunologic observations. Am. J. Pathol. 49:871–888 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirsch MS. 2005. Cytomegalovirus and human herpesvirus types 6, 7, and 8, p 1049–1053 In Kasper DL, et al. (ed), Harrison's principles of internal medicine, 16th ed McGraw-Hill, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hokeness KL, et al. 2007. CXCR3-dependent recruitment of antigen-specific T lymphocytes to the liver during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 81:1241–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hokeness KL, Kuziel WA, Biron CA, Salazar-Mather TP. 2005. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and CCR2 interactions are required for IFN-alpha/beta-induced inflammatory responses and antiviral defense in liver. J. Immunol. 174:1549–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hokeness-Antonelli KL, Crane MJ, Dragoi AM, Chu W-M, Salazar-Mather TP. 2007. IFN-αβ-mediated inflammatory responses and antiviral defense in liver is TLR9-independent but MyD88-dependent during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Immunol. 179:6176–6183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holtappels R, Böhm V, Podlech J, Reddehase MJ. 2008. CD8 T-cell-based immunotherapy of cytomegalovirus infection: “proof of concept” provided by the murine model. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197:125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holtappels R, et al. 1998. Control of murine cytomegalovirus in the lungs: relative but not absolute immunodominance of the immediate-early 1 nonapeptide during the antiviral cytolytic T-lymphocyte response in pulmonary infiltrates. J. Virol. 72:7201–7212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsu KM, Pratt JR, Akers WJ, Achilefu SI, Yokoyama WM. 2009. Murine cytomegalovirus displays selective infection of cells within hours after systemic administration. J. Gen. Virol. 90:33–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones CA. 2003. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 33:70–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jonjić S, Mutter W, Weiland F, Reddehase MJ, Koszinowski UH. 1989. Site-restricted persistent cytomegalovirus infection after selective long-term depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 169:1199–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaiser WJ, et al. 2011. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature 471:368–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kanno A, Abe M, Yamada M, Murakami K. 1997. Clinical and histological features of cytomegalovirus hepatitis in previously healthy adults. Liver 17:129–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klenerman P, Hill A. 2005. T cells and viral persistence: lessons from diverse infections. Nat. Immunol. 6:873–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamb SG, Stern H. 1966. Cytomegalovirus mononucleosis with jaundice as presenting sign. Lancet ii:1003–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lanier LL. 2008. Evolutionary struggles between NK cells and viruses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:259–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee S-O, Razonable RR. 2010. Current concepts on cytomegalovirus infection after liver transplantation. World J. Hepatol. 2:325–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lin KL, Suzuki Y, Nakano H, Ramsburg E, Gunn MD. 2008. CCR2+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells and exudate macrophages produce influenza-induced pulmonary immune pathology and mortality. J. Immunol. 180:2562–2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loewendorf AI, et al. 2011. The mouse cytomegalovirus m155 glycoprotein inhibits CD40 expression and restricts CD4 T cell responses. J. Virol. 85:5208–5212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Manning WC, Stoddart CA, Lagenaur LA, Abenes GB, Mocarski ES. 1992. Cytomegalovirus determinant of replication in salivary glands. J. Virol. 66:3794–3802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maul GG, Negorev D. 2008. Differences between mouse and human cytomegalovirus interactions with their respective hosts at immediate early times of the replication cycle. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197:241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCordock HA, Smith MG. 1936. The visceral lesions produced in mice by the salivary gland virus of mice. J. Exp. Med. 63:303–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mims CA, Gould J. 1978. Splenic necrosis in mice infected with cytomegalovirus. J. Infect. Dis. 137:587–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mintern JD, et al. 2006. Viral interference with B7-1 costimulation: a new role for murine cytomegalovirus fc receptor-1. J. Immunol. 177:8422–8431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Misra V, Hudson JB. 1980. Minor base sequence differences between the genomes of two strains of murine cytomegalovirus differing in virulence. Arch. Virol. 64:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mitrović M, et al. 2012. The NK cell response to mouse cytomegalovirus infection affects the level and kinetics of the early CD8+ T-cell response. J. Virol. 86:2165–2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Pass RF. 2007. Cytomegaloviruses, p 2701–2772 In Knipe DM, et al. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Williams, Philadephia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 46. Munks MW, et al. 2006. Four distinct patterns of memory CD8 T cell responses to chronic murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Immunol. 177:450–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Noda S, et al. 2006. Cytomegalovirus MCK-2 controls mobilization and recruitment of myeloid progenitor cells to facilitate dissemination. Blood 107:30–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Orange JS, Biron CA. 1996. Characterization of early IL-12, IFN-alphabeta, and TNF effects on antiviral state and NK cell responses during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Immunol. 156:4746–4756 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Orange JS, Salazar-Mather TP, Opal SM, Biron CA. 1997. Mechanisms for virus-induced liver disease: tumor necrosis factor-mediated pathology independent of natural killer and T cells during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 71:9248–9258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Orange JS, Wang B, Terhorst C, Biron CA. 1995. Requirement for natural killer cell-produced interferon gamma in defense against murine cytomegalovirus infection and enhancement of this defense pathway by interleukin 12 administration. J. Exp. Med. 182:1045–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Osborn J, Walker D. 1971. Virulence and attenuation of murine cytomegalovirus. Infect. Immun. 3:228–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pavić I, et al. 1993. Participation of endogenous tumour necrosis factor alpha in host resistance to cytomegalovirus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 74(Part 10):2215–2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Penfold ME, et al. 1999. Cytomegalovirus encodes a potent alpha chemokine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9839–9844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Plotkin SA, Starr SE, Friedman HM, Gonczol E, Weibel RE. 1989. Protective effects of Towne cytomegalovirus vaccine against low-passage cytomegalovirus administered as a challenge. J. Infect. Dis. 159:860–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Razonable RR. 2011. Management of viral infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 9:685–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Reddehase MJ. 2002. Antigens and immunoevasins: opponents in cytomegalovirus immune surveillance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:831–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Reddehase MJ, Mutter W, Münch K, Bühring HJ, Koszinowski UH. 1987. CD8-positive T lymphocytes specific for murine cytomegalovirus immediate-early antigens mediate protective immunity. J. Virol. 61:3102–3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Reddehase MJ, Rothbard JB, Koszinowski UH. 1989. A pentapeptide as minimal antigenic determinant for MHC class I-restricted T lymphocytes. Nature 337:651–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Redpath S, Angulo A, Gascoigne NR, Ghazal P. 1999. Murine cytomegalovirus infection down-regulates MHC class II expression on macrophages by induction of IL-10. J. Immunol. 162:6701–6707 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Roth E, Pircher H. 2004. IFN-gamma promotes Fas ligand- and perforin-mediated liver cell destruction by cytotoxic CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 172:1588–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Saederup N, Lin YC, Dairaghi DJ, Schall TJ, Mocarski ES. 1999. Cytomegalovirus-encoded beta chemokine promotes monocyte-associated viremia in the host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:10881–10886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Salazar-Mather TP, Hamilton TA, Biron CA. 2000. A chemokine-to-cytokine-to-chemokine cascade critical in antiviral defense. J. Clin. Invest. 105:985–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Salazar-Mather TP, Ishikawa R, Biron CA. 1996. NK cell trafficking and cytokine expression in splenic compartments after IFN induction and viral infection. J. Immunol. 157:3054–3064 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Salazar-Mather TP, Lewis CA, Biron CA. 2002. Type I interferons regulate inflammatory cell trafficking and macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha delivery to the liver. J. Clin. Invest. 110:321–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Salazar-Mather TP, Orange JS, Biron CA. 1998. Early murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection induces liver natural killer (NK) cell inflammation and protection through macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha (MIP-1alpha)-dependent pathways. J. Exp. Med. 187:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Selgrade MK, Ahmed A, Sell KW, Gershwin ME, Steinberg AD. 1976. Effect of murine cytomegalovirus on the in vitro responses of T and B cells to mitogens. J. Immunol. 116:1459–1465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Selgrade MK, Collier AM, Saxton L, Daniels MJ, Graham JA. 1984. Comparison of the pathogenesis of murine cytomegalovirus in lung and liver following intraperitoneal or intratracheal infection. J. Gen. Virol. 65(Part 3):515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Selgrade MK, Nedrud JG, Collier AM, Gardner DE. 1981. Effects of cell source, mouse strain, and immunosuppressive treatment on production of virulent and attenuated murine cytomegalovirus. Infect. Immun. 33:840–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shanley JD, Biczak L, Forman SJ. 1993. Acute murine cytomegalovirus infection induces lethal hepatitis. J. Infect. Dis. 167:264–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shanley JD, Goff E, Debs RJ, Forman SJ. 1994. The role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in acute murine cytomegalovirus infection in BALB/c mice. J. Infect. Dis. 169:1088–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Skaletskaya A, et al. 2001. A cytomegalovirus-encoded inhibitor of apoptosis that suppresses caspase-8 activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:7829–7834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Smith HR, et al. 2002. Recognition of a virus-encoded ligand by a natural killer cell activation receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:8826–8831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Smith SC, Allen PM. 1991. Myosin-induced acute myocarditis is a T cell-mediated disease. J. Immunol. 147:2141–2147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Snyder C, et al. 2009. CD4+ T cell help has an epitope-dependent impact on CD8+ T cell memory inflation during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Immunol. 183:3932–3941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Starr SE, Allison AC. 1977. Role of T lymphocytes in recovery from murine cytomegalovirus infection. Infect. Immun. 17:458–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stoddart CA, et al. 1994. Peripheral blood mononuclear phagocytes mediate dissemination of murine cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 68:6243–6253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sumaria N, et al. 2009. The roles of interferon-gamma and perforin in antiviral immunity in mice that differ in genetically determined NK-cell-mediated antiviral activity. Immunol. Cell Biol. 87:559–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. 2010. Virus inhibition of RIP3-dependent necrosis. Cell Host Microbe 7:302–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Walsh CM, et al. 1994. Immune function in mice lacking the perforin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:10854–10858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. 2003. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J. Virol. 77:4911–4927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wingard JR, Bender WJ, Saral R, Burns WH. 1981. Efficacy of acyclovir against mouse cytomegalovirus in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 20:275–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yang W, et al. 2011. Interferon-gamma negatively regulates Th17-mediated immunopathology during mouse hepatitis virus infection. J. Mol. Med. 89:399–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zinkernagel RM, et al. 1986. T cell-mediated hepatitis in mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Liver cell destruction by H-2 class I-restricted virus-specific cytotoxic T cells as a physiological correlate of the 51Cr-release assay? J. Exp. Med. 164:1075–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]