Abstract

Earlier studies reported that ICP0, a key regulatory protein encoded by herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), binds ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7). The fundamental conclusion of these studies is that depletion of USP7 destabilized ICP0, that ICP0 mediated the degradation of USP7, and that amino acid substitutions in ICP0 that abolished binding to USP7 significantly impaired the ability of HSV-1 to replicate. We show here that, indeed, depletion of USP7 leads to reduction of ICP0 and that USP7 is degraded in an ICP0-dependent manner. However, overexpression of USP7 or substitution in ICP0 of a single amino acid to abolish binding to USP7 accelerated the accumulation of viral mRNAs and proteins at early times after infection and had no deleterious effect on virus yields. A clue as to why USP7 is degraded emerged from the observation that, notwithstanding the accelerated expression of viral genes, the plaques formed by the mutant virus were very small, implying a defect in virus transmission from cell to cell.

INTRODUCTION

Two key events augur successful replication of herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and -2) in cells in culture. The first is sequential derepression of viral genes comprising different kinetic classes. The second event is a preemptive strike to prevent innate immune responses to the virus (14, 25, 26). One of the viral proteins that plays a key role in both processes is infected cell protein 0 (ICP0). The fundamental functions of ICP0, an α (immediate-early) protein, are 3-fold. Specifically, (i) ICP0 causes the derepression of β and γ genes, (ii) it degrades or mediates the degradation of cellular proteins that could mount an antiviral response to infection, and (iii) it recruits to the site of development of the viral replication compartments cellular proteins (e.g., cyclin D3, CDK4, BMAL1, and the CLOCK histone acetyltransferase) that ultimately play significant roles in viral replication (5, 6, 9, 11–13, 18–22, 25). As expected, ICP0 interacts with a large number of host proteins. One of the earliest cellular partners discovered to date is ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7) (8).

The interaction of ICP0 with USP7 was studied in detail by Boutell and Everett (2, 3), Canning et al. (4), and Everett and colleagues (8). The fundamental conclusions of these studies are as follows. (i) A mutant virus carrying a single amino acid substitution and that no longer binds USP7 is significantly impaired in its ability to replicate (1, 8). (ii) ICP0 degrades USP7 in an ICP0 RING finger (RF)- and proteasome-dependent manner. (iii) USP7 stabilizes ICP0, and this is the dominant outcome of the interaction between the two proteins (1, 4, 8). (iv) ICP0 mediates the ubiquitination of p53 in a USP7-independent manner (2, 3). To date, no other cellular protein has been shown to be either stabilized or degraded as a consequence of the interaction of ICP0 with USP7. Other studies potentially relevant to the replication of HSV have shown that depletion of USP7 increases the amount of PML, the major component of the ND10 bodies, whereas overexpression of USP7 causes a decrease in the amount of PML (27). Another observation relevant to the biology of HSV is the report that USP7 stabilizes REST and promotes the maintenance of neuronal progenitor cells (16). REST is a component of the histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) or HDAC2-CoREST-LSD1-REST repressor complex. One of the key functions of ICP0 is to bind CoREST and displace HDACs from the repressor complex to enable the derepression of β and γ genes (25, 26).

The initial objectives of the studies described in this report were to define in more detail the functions of USP7. The vexing questions posed by the studies by Boutell et al. and Everett and colleagues (1, 8) were, if USP7 is essential for the stability of ICP0, why does it turn over very rapidly at early times after infection (10)? Furthermore, if the loss of the interactions with USP7 has a deleterious effect on virus growth, why target USP7 for degradation?

We report here that, indeed, depletion of USP7 leads to an apparent decrease in the accumulation of ICP0. However, in contrast to the studies of Boutell et al. and Everett and colleagues (1, 8) overexpression of USP7 resulting from transfection of the USP7 gene or mutation of the USP7 binding site in ICP0 by a single codon substitution results in an increase in the rate of synthesis of viral RNA and proteins during the early stages of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

The sources and propagation of HEp-2, Vero, HEL, and HEK-293 cells and rabbit skin cells (RSC) were reported previously (18). HSV-1(F), a limited-passage isolate, is the prototype strain used in our laboratory (7). The properties of R7910, a ΔICP0-null mutant virus, and the RING finger C116A/C156A, a gift from Saul Silverstein, were described previously (23, 24).

Construction of recombinant viruses.

pRB3710 encodes a SacI-PstI fragment containing the entire ICP0 coding sequence in vector pUC18 (15). pRB5343 contains the K620I point mutation in the full-length ICP0 encoded by pRB3710 and was described elsewhere (15). The plasmid pRB5270, designed to restore ICP0 coding sequences within the ICP0-null recombinant virus R7910, carrying the HSV-1(F) BsrGI fragment encoding the ICP0 gene and flanking sequences cloned in the Acc65I site of the vector pUC19, was described previously (28). The SnaBI/BsmI fragment of pRB5343 was purified and ligated to SnaBI/BsmI-digested pRB5270 plasmid. The resultant plasmid, pRB5344, carrying the K620I mutation in the ICP0 sequence, was sequenced at the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center DNA Sequencing facility to confirm that it contained the appropriate mutation in ICP0. The recombinant virus R6702 was constructed by transfecting RSC with 2 μg of pRB5344 using Lipofectamine Plus (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by superinfection with R7910 at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, as described previously (28). After 2 days, transfections were frozen at −80°C, thawed, sonicated, and titrated onto Vero cells. Large plaques were isolated from dishes containing 20 to 50 plaques and grown on Vero cells. Viral isolates were screened for ICP0 expression by probing electrophoretically separated lysates of infected Vero cells with antibody directed against ICP0. After the initial screen, an additional round of plaque purification and screening for ICP0 was performed. The K620I substitution in the R6702 ICP0 sequence was verified by sequencing, as illustrated in Fig. 1A.

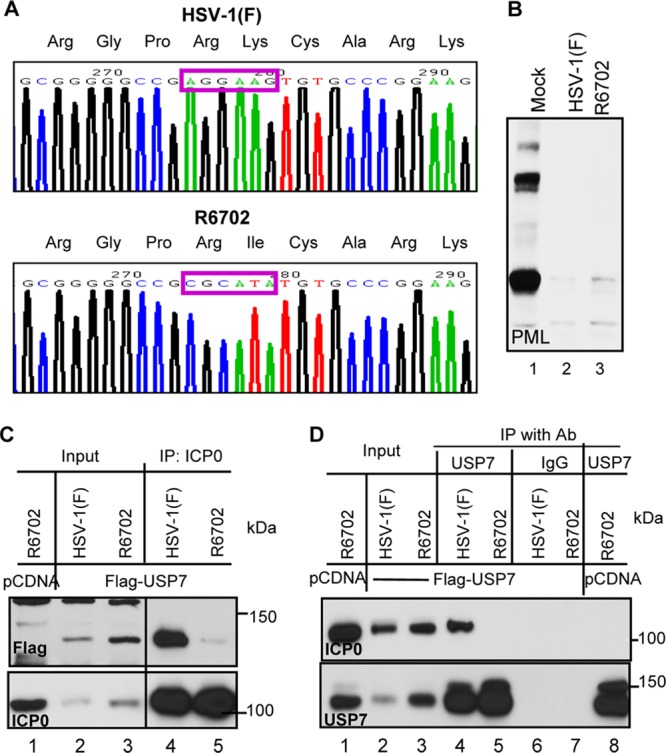

Fig 1.

Construction and characterization of a USP7 binding-defective recombinant virus, R6702. (A) Sequence chromatographs of HSV-1(F) and R6702. The mutation from a lysine residue in HSV-1(F) into an isoleucine residue in R6702 is highlighted by purple rectangles. (B) Viral protein expression and PML degradation of R6702. pHEL cells were infected with HSV-1(F) or R6702 at 5 PFU/cell. At 6 h postinfection, the cells were lysed, and total cell lysates were probed with various antibodies, as indicated. (C and D) Interaction between ICP0 and USP7 in HSV-1(F) and R6702. HEp-2 cells transfected with Flag-tagged USP7 or pcDNA3.1 were infected with HSV-1(F) or R6702. At 18 h postinfection, cells were harvested, washed, and lysed by brief sonication. Total cell lysates were cleared and reacted with either anti-ICP0 antibody (Ab) (C) or anti-USP7 antibody (D) for immunoprecipitation (IP). Rabbit IgG (IgG) was used as a negative control. The immunoprecipitates were probed for USP7, Flag, or ICP0 as indicated.

Transfection-infection experiments.

HEK-293 cells grown in 6-well plates were transfected when 60 to 70% confluent with 2 μg of pCI-Flag USP7 (Addgene), pcDNA-Myc USP7 (kindly provided by Boudewijn M. T. Burgering), or the control plasmid pcDNA-mCherry (Invitrogen) in mixtures of 6 μl of Plus reagents and 4 μl Lipofectamine per well. At 3 h after transfection, the medium was removed, and the cells were further incubated with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 48 h. The cells were then exposed to 5 or 10 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell in medium 199V, consisting of mixture 199 (Sigma) supplemented with 1% calf serum. Samples were collected at time intervals indicated in the figure legends after exposure to the virus and processed for immunoblot analyses or RNA quantification analyses as detailed below.

For the immunoprecipitation analyses, HEp-2 cells were transfected with a Flag-tagged USP7-expressing plasmid (a generous gift from Wei Gu) or with the empty vector pcDNA3.1, as described above. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were infected with 10 PFU of virus per cell and incubated for 18 h.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Transfected or infected cells were lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5% NP-40, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM glycerol phosphate, 10 μM protease inhibitor cocktail). After brief sonication and centrifugation, the cell debris was discarded. The supernatant fluids were reacted with a protein A-Sepharose CL-4B 50% slurry (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) at 4°C for 20 min to clear the lysates. Upon removal of the beads, the lysates were reacted with either a rabbit polyclonal antibody to USP7 (Upstate) or a rabbit polyclonal antibody to ICP0 (Goodwin Institute for Cancer Research, Plantation, FL), as indicated in Results, overnight at 4°C. The lysate-antibody mixtures were incubated with 50 μl of protein A-Sepharose CL-4B 50% slurry at 4°C for 1 h. The beads were then rinsed four times with the same buffer and eluted with 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer at 95°C for 5 min. The precipitates were loaded on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel and examined by Western blotting.

Immunoblot analysis.

The immunoblot procedures were described previously (20). Briefly, cells were harvested at the indicated times after infection, rinsed with PBS, solubilized in triple-detergent buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 100 μg ml of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride−1) supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (10 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM sodium vanadate) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) as specified by the manufacturer, and briefly sonicated. The protein concentrations in total cell lysates were determined with the aid of the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Approximately 60 μg of proteins per sample was subjected to further analysis. Proteins were electrophoretically separated in denaturing polyacrylamide gels, electrically transferred to nitrocellulose sheets, blocked with PBS supplemented with 0.02% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBST) and 5% nonfat milk, and reacted overnight at 4°C with the appropriate primary antibodies diluted in PBST-1% nonfat milk. The rabbit polyclonal antibodies to USP7 (Upstate), PML (Santa Cruz), and REST (Novus Biologicals) and the mouse monoclonal antibodies to Flag (Invitrogen) and USP7 (Santa Cruz) were used at 1:500 dilution. The mouse monoclonal antibody to β-actin (Sigma) was used at a 1:1,000 dilution. The ICP4 and US11 mouse monoclonal antibodies and the US3 and ICP0 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Goodwin Institute for Cancer Research, Plantation, FL) were used at 1:1,000 dilution. After several rinses with PBST-1% nonfat milk, the membranes were reacted with the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated either to alkaline phosphatase or to horseradish peroxidase. Finally, protein bands were visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP)–nitroblue tetrazolium (Denville Scientific, Inc.) or with ECL Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence assays.

The immunofluorescence assay procedures were described elsewhere (18). Briefly, cells seeded on 4-well slides (Erie Scientific) were exposed to 10 PFU of virus per cell and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at the times indicated in Results; permeabilized; blocked with PBS-TBH solution consisting of 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, 10% horse serum, and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA); and reacted with primary antibodies diluted in PBS-TBH. The ICP0 exon 2 rabbit polyclonal antibody was used at a 1:2,000 dilution. The USP7 and PML mouse monoclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used at a 1:500 dilution. The four-well cultures were then rinsed several times with PBS-TBH and reacted with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-TBH. After several rinses, first with PBS-TBH and then with PBS, the samples were mounted and examined with a Zeiss confocal microscope equipped with software provided by Zeiss.

Depletion of USP7 by siRNA.

The On Target plus Smart pool human USP7 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and the nontarget control were purchased from Dharmacon. The siRNA transfections were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Briefly, 10 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was diluted in 250 μl Opti-MEM I medium (Gibco) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Next, 100 pmol of either USP7 siRNA or control siRNA diluted in Opti-MEM I was added gently to the Lipofectamine mixture and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The oligomer-Lipofectamine complexes were added to cells seeded on 6-well plates at 40 to 50% confluence. Approximately 72 h after the transfection, the cells were infected with wild-type virus (10 PFU/cell) and harvested at the indicated time points, and equal amounts of total proteins were analyzed for the abundances of host and viral proteins and the efficiency of USP7 depletion.

Total-RNA extraction and real-time PCR analysis.

The total-RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis procedures were described previously (21). Briefly, total RNA was extracted with the aid of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNase treatment (Promega), phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction (Ambion), and ethanol precipitation (Fisher Scientific) were done to remove possible DNA contamination. First-strand cDNA synthesis using 2 μg of total RNA and oligo(dT) was done with the SuperScriptIII first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen), according to the supplier's instructions. Equal volumes of the cDNA synthesis mixtures were used for quantification of the viral ICP0, thymidine kinase (TK), and gI gene transcripts with the SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMix Universal (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples without reverse transcription served as controls. The primers for ICP0 were 5′-AAGCTTGGATCCGAGCCCCGCCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGCGGTGCATGCACGGGAAGGT-3′ (reverse), those for the TK were 5′-CTTAACAGCGTCAACAGCGTGCCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAAAGAGGTGCGGGAGTTT-3′ (reverse), and those for gI were 5′-CCCACGGTCAGTCTGGTATC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTGTGTCCCATGGGGTAGT-3′ (reverse). All the transcripts were normalized to the 18S rRNA levels. The 18S rRNA primers (Universal Primers; Ambion) were modified according to the supplier's instructions to be suitable as internal controls for mRNA species of any abundance. The assays were performed on a StepOnePlus system (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed with software provided by the supplier.

DNA quantification analysis.

HEp-2 cells were exposed to 5 PFU of either HSV-1(F) or R6702 per cell. Samples were collected at 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 9 h after infection. For total-DNA extraction, the cells were incubated with lysis buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mΜ EDTA, pH 8, 0.5% SDS, 200 μg/ml proteinase K, and 20 μg/ml RNase A overnight at 37°C. Phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation were done to purify the DNA. For the relative quantification of the viral DNA, equal amounts of DNA per sample were used in real-time PCR analysis. For the detection of the viral DNA, the primers used corresponded to the TK region: TK (forward), 5′-CTTAACAGCGTCAACAGCGTGCCG-3′, and TK (reverse), 5′-CCAAAGAGGTGCGGGAGTTT-3′. The human β-actin gene served as an internal control, and the primers used were β-actin (forward), 5′-CTATCCCTGTACGCCTCTGG-3′, and β-actin (reverse), 5′-TGGTGGTGAAGCTGTAGCC-3′.

RESULTS

Characterization of the R6702 mutant virus.

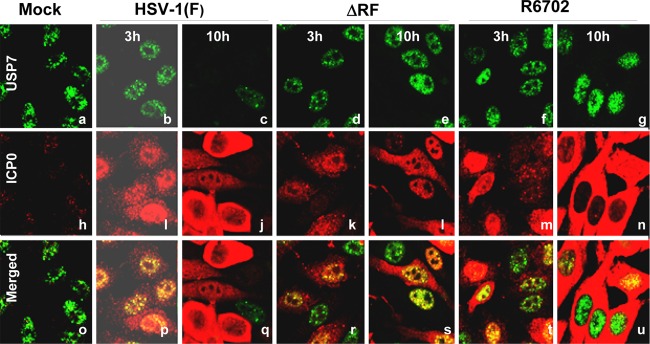

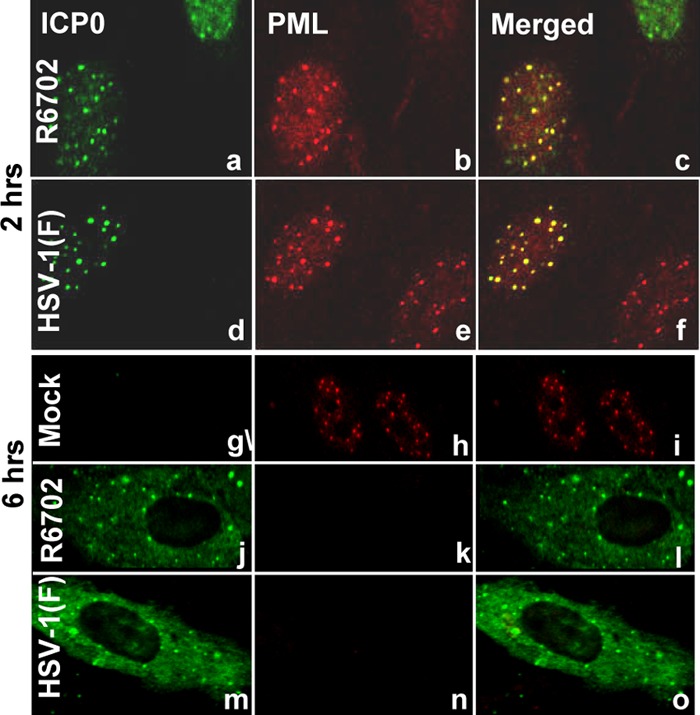

Studies reported elsewhere showed that USP7 physically interacts with ICP0 and that mutations in ICP0 at residues 620 to 626 abolished this interaction (1, 8). We constructed a mutant virus in which Lys620 was replaced with Ile. The properties of the R6702 mutant bear on the validity of the results reported here and are therefore presented in detail in Fig. 1, 2, and 3. Specifically, they are as follows. (i) Sequencing studies shown in part in Fig. 1A indicated that the only codon substitution between amino acids 514 and 775 is that of isoleucine in place of lysine at position 620. (ii) Immunoblots of infected HEL cell lysates harvested at 6 h after infection and reacted with anti-PML antibody (Fig. 1B) showed that both HSV-1(F) and R6702 degrade PML. (iii) In this series of experiments, HEp-2 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged USP7 or the empty vector pcDNA and then infected with HSV-1(F) or R6702 mutant virus. Lysates harvested 18 h after infection were reacted with antibody to ICP0 (Fig. 1C) or to Flag-tagged USP7 (Fig. 1D). The results showed that the antibody to ICP0 coprecipitated the Flag-tagged USP7 from wild-type virus-infected cells (Fig. 1C, lane 4), but not from R6702-infected cells (Fig. 1C, lane 5). Conversely, antibody to USP7 coprecipitated ICP0 from lysates of cells infected with wild-type virus (Fig. 1D, lane 4), but not from lysates of R6702 mutant-virus-infected cells (Fig. 1D, lane 5). The immunoprecipitation reactions with control IgGs were negative (Fig. 1D, lanes 6 and 7). (iv) The results illustrated in Fig. 2 indicate that PML was present and colocalized with ICP0 in infected HEL cells at 2 h after infection (Fig. 2c and f) but could no longer be detected at 6 h after infection (Fig. 2o and l). Concurrently, ICP0 of both viruses was entirely intranuclear at 2 h after infection (Fig. 2c and f) and cytoplasmic at 6 h after infection (Fig. 2o and l). (v) Consistent with previous reports, the immunofluorescence studies shown in Fig. 3 indicate that USP7 was not degraded in HEp-2 cells infected with the R6702 mutant. In these studies, cells grown on 4-well slides were exposed to wild-type virus or RF or R6702 mutant virus. The cultures were fixed and reacted with antibodies to ICP0 and USP7 at 3 or 10 h after infection. The results showed that USP7 was detected at 10 h after infection in cells infected with RF (Fig. 3e and s) or R6702 (Fig. 3g and u) mutant virus, but not in cells infected with the wild-type virus (Fig. 3c and q).

Fig 2.

R6702 ICP0 localization is similar to that of wt ICP0. pHEL cells seeded in 4-well slides were infected with 10 PFU of either HSV-1(F) (d to f and m to o) or R6702 (a to c and j to l) per cell. The cells were fixed at 2 h (a to f) or at 6 h (j to o) after exposure to the viruses, permeabilized, and reacted simultaneously with the rabbit polyclonal antibody to ICP0 and the mouse monoclonal antibody to PML. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit and Texas Red-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies were used as secondary antibodies. The images were taken with an LSM 410 Zeiss confocal microscope.

Fig 3.

R6702 ICP0 does not degrade USP7. HEp-2 cells seeded in 4-well slides were either mock infected (a, h, and o) or exposed to 10 PFU per cell of either HSV-1(F) (b, c, i, j, p, and q), RF (d, e, k, l, r, and s), or R6702 (f, g, m, n, t, and u). The cells were fixed at 3 h (b, i, p, d, k, r, f, m, and t) or at 10 h (c, j, q, g, n, u, a, h, o, e, l, and s) after exposure to the viruses, permeabilized, and reacted simultaneously with the rabbit polyclonal antibody to ICP0 and the mouse monoclonal antibody to USP7. Alexa-Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or Alexa-Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse was used as a secondary antibody. The images were taken with an LSM 410 Zeiss confocal microscope.

The results of these studies indicate that the ICP0 encoded by the recombinant R6702 carries a single codon substitution and resembles the wild-type ICP0 with respect to intracellular localization and degradation of PML. As predicted from earlier studies, ICP0 encoded by the R6702 mutant virus does not interact with or mediate the degradation of USP7.

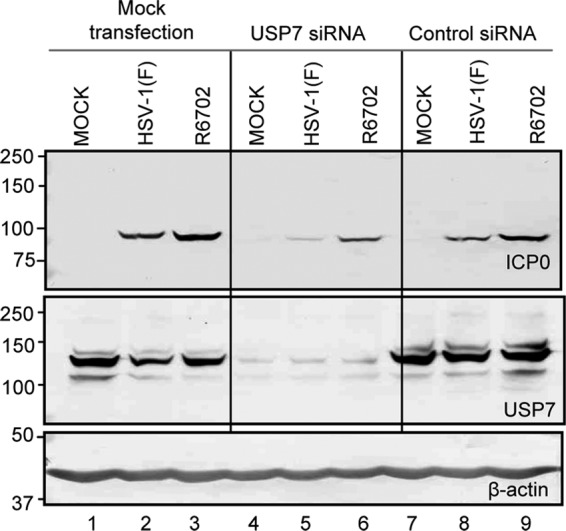

Effect of USP7 depletion on the stability of ICP0.

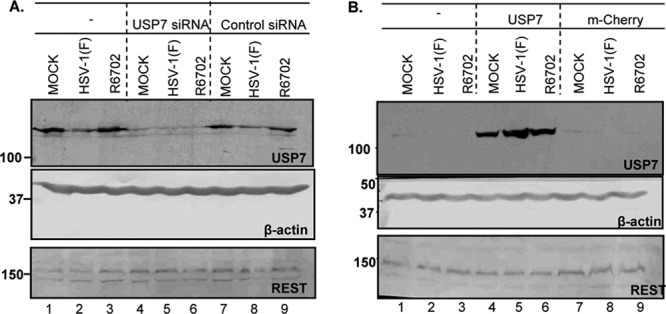

In this series of experiments, we sought to address the impact of USP7 depletion on ICP0 accumulation in cells infected with the wild type or the R6702 mutant. Thus, HEp-2 cells were mock transfected or transfected with USP7 or control siRNA and then infected with wild-type virus or the R6702 mutant. Samples were collected at 10 h after infection, and equal amounts of proteins were analyzed for the abundance of ICP0 and the efficiency of USP7 depletion. The results (Fig. 4) show that USP7 depletion results in decreased ICP0 accumulation in both wild-type- and R6702-infected cells (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 6). Some decrease in the levels of ICP0 was also observed in cells transfected with control siRNA. In essence, depletion of USP7 downregulated the accumulation of ICP0. In none of the experiments done in these studies did we find that depletion of USP7 upregulates the accumulation of ICP0.

Fig 4.

Knockdown of USP7 and its effect on ICP0 accumulation. HEp-2 cells were mock transfected or transfected with either USP7 siRNA or nontarget control siRNA for 96 h before being mock infected or infected with HSV-1(F) or R6702 for 10 h. Cells were harvested, lysed, and immunoblotted with the antibodies indicated. Equal amounts of HEp-2 cells that were infected without any prior treatment (lanes 1 to 3) served as controls.

Overexpression of USP7 accelerates transcription of the viral genes.

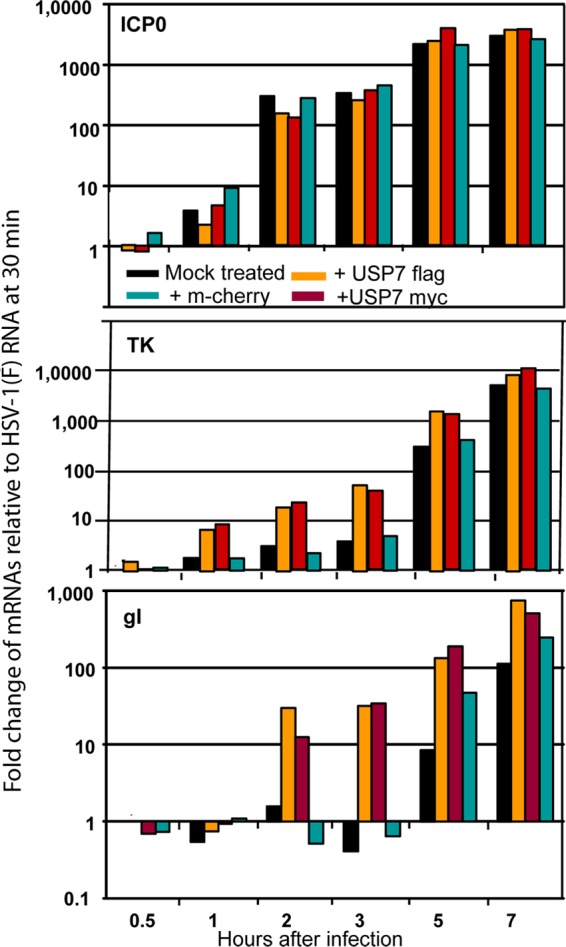

To test the effects of overexpression of USP7, two series of experiments were done. In the first, replicate cultures of 293T cells were transfected with identical amounts of DNA consisting of plasmids encoding USP7 tagged with either myc or Flag. A plasmid encoding mCherry served as a control. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were exposed to wild-type or R6702 mutant virus. At 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 h after infection, the cells were harvested, and mRNA was extracted and analyzed by qRT-PCR for the amount of ICP0, TK, or gI mRNA. The results (Fig. 5) were as follows. (i) Overexpression of USP7, whether Flag or myc tagged, had no significant effect on the accumulation of ICP0 mRNA at all time points tested. (ii) The TK and gI mRNAs tested in these studies are encoded by β and γ genes, respectively. The accumulation of these mRNAs lags behind that of ICP0, an α gene product. In the cases of both TK and gI, the amounts of mRNA accumulated at early times were significantly greater in cells transfected with USP7 tagged with either myc or Flag. At 2 and 3 h after infection, the amount of TK or gI mRNA accumulated in cells transfected with tagged USP7 was at least 10-fold greater than in the case of untransfected controls or cells transfected with the plasmid encoding mCherry. This difference disappeared by 7 h after infection.

Fig 5.

USP7 overexpression increases the rates of HSV-1(F) gene transcription. HEK-293 cells seeded in 6-well plates were transfected either with USP7 Flag- or with USP7 myc-expressing plasmids. Transfections with an mCherry-expressing plasmid or nontransfected cells served as controls. The cells were infected with 3 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell at 48 h posttransfection. Samples were collected 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 5 h, and 7 h after exposure to the virus, and total RNA was extracted and converted to cDNA as described in Materials and Methods; equal amounts of the cDNA were used as templates for quantification of the viral gene transcripts ICP0, TK, and gI. 18s rRNA was used for the normalization process. The results represent the fold change of the viral gene transcripts relative to the respective HSV-1(F) mRNA in mock-treated cells at 30 min after infection.

We conclude that overexpression of USP7 had no effect on the accumulation of ICP0 mRNA but accelerated the accumulation of mRNAs made at later times after infection.

The effects of stabilization of USP7 in cells infected with the R6702 mutant were similar to those observed in cells overexpressing USP7.

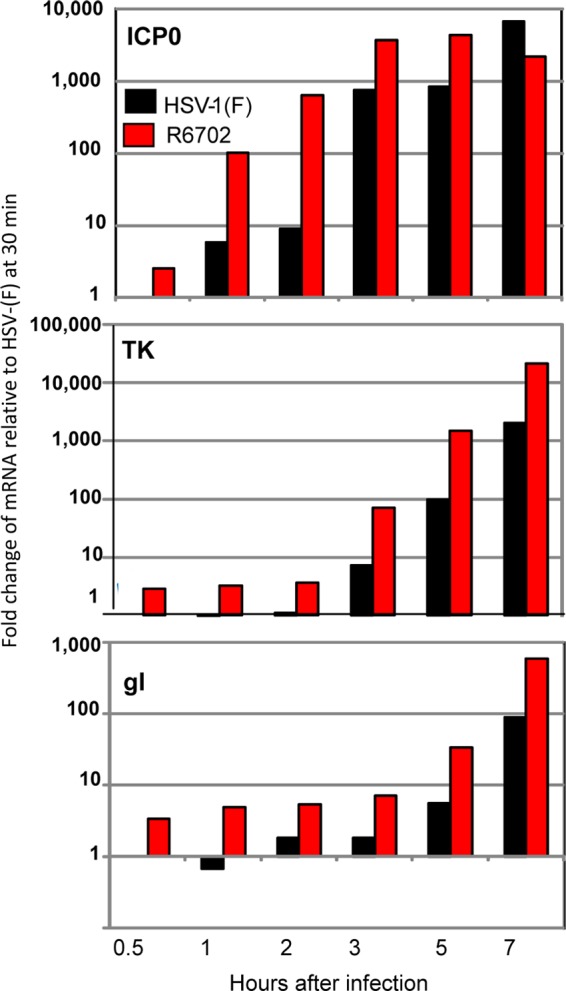

In the second series of experiments, replicate cultures of HEp-2 cells were exposed to 5 PFU of HSV-1(F) or R6702 per cell. The cells were harvested at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, or 7 h after infection, and extracted RNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR. The results, shown in Fig. 6, paralleled those observed in cells in which USP7 was overexpressed by transfection (Fig. 5). The significant difference is that in infected cells, the amount of ICP0 mRNA encoded by R6702 mutant virus was more than 10-fold greater during the first 2 h than in cells infected with the wild-type virus. Higher levels of TK or gI mRNA were also detected in cells infected with the mutant virus.

Fig 6.

Accelerated viral gene transcription in R6702-infected cells. HEp-2 cells seeded in 6-well plates were exposed to 5 PFU of either HSV-1(F) or R6702 per cell. Samples were harvested at 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 5 h, or 7 h after infection and processed for total RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and viral gene transcript quantification, as described in Materials and Methods. The results represent the fold change of the viral gene transcripts relative to the respective HSV-1(F) mRNA at 30 min after infection.

We conclude on the basis of these experiments that stabilization or overexpression of USP7 leads to accelerated transcription of viral genes.

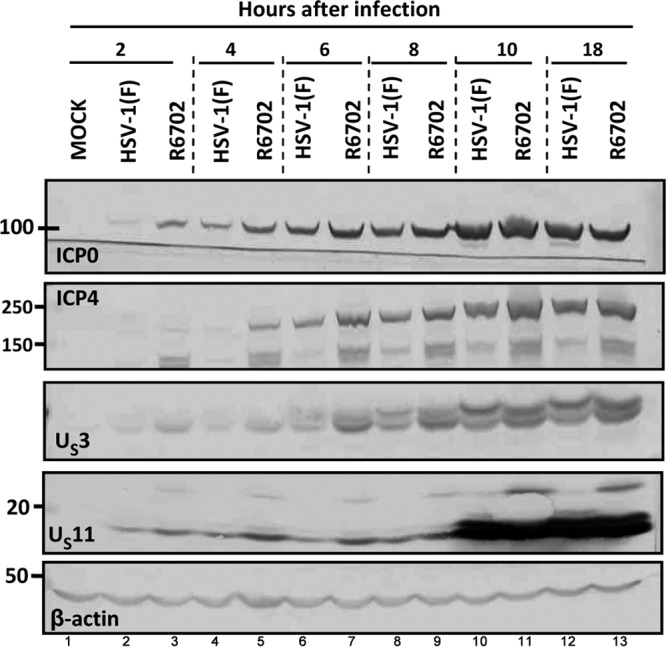

Accelerated transcription of viral genes in cells in which USP7 was stabilized is matched by higher levels of accumulation of viral proteins.

In another series of experiments, HEp-2 cells were exposed to 5 PFU of wild-type or R6702 mutant virus per cell. At the intervals after infection indicated in Fig. 7, replicate cultures were harvested and solubilized. The proteins electrophoretically separated in denaturing gels were probed with antibodies to ICP0, ICP4, US3, and US11 proteins. β-Actin served as a loading control. The results shown in Fig. 7 were as follows. (i) Until at least 10 h after infection, the amounts of viral proteins accumulated in cells infected with the R6702 mutant were greater than in cells infected with wild-type virus. (ii) The US11 protein in cells infected with the R6702 mutant formed a lighter, more slowly migrating band that reacted with the US11 antibody. This band was not seen in wild-type virus-infected cells. In contrast, US3 protein accumulating at 6, 8, and 10 h in R6702 virus-infected cells migrated faster than the corresponding protein from wild-type virus-infected cells. This difference in electrophoretic mobility largely disappeared in lysates harvested 18 h after infection. The results suggest that proteins accumulated in cells infected with the R6702 mutant virus may differ in the rate of posttranslational modifications to which they are normally subjected.

Fig 7.

Early accumulation of viral gene products in R6702-infected cells. HEp-2 cells were either mock infected or exposed to 5 PFU of HSV-1(F) or R6702 per cell. Samples were harvested at 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 10 h, or 18 h after infection, and approximately 60 μg total proteins per sample was electrophoretically separated on 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, electrically transferred to nitrocellulose sheets, and immunoblotted with ICP0, ICP4, US3, or US11 antibodies. β-Actin served as a loading control.

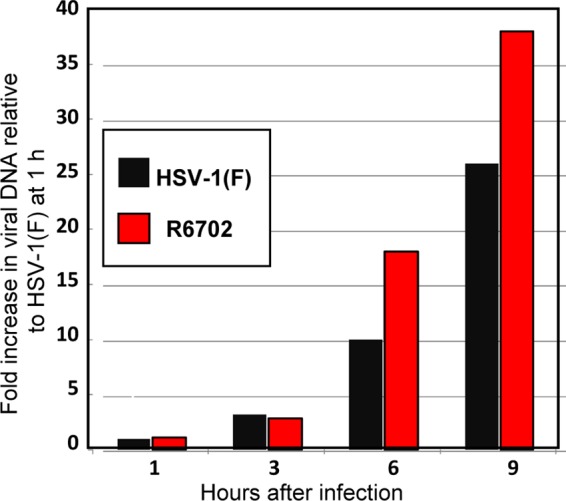

Viral DNA accumulated at higher rates in cells infected with the R6702 mutant virus.

In another series of experiments, we sought to determine whether the rate of accumulation of viral DNA in cells infected with the R6702 mutant virus is in concordance with the accelerated accumulation of viral gene products. For this purpose, HEp-2 cells were infected at 5 PFU/cell with either the wild-type virus or the R6702 mutant virus. The cells were harvested at 1, 3, 6, or 9 h after infection. Total DNA was extracted, and the viral DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR using primers for the viral thymidine kinase gene. The β-actin gene served as an internal control and was used for the normalization process. The results (Fig. 8) show that the R6702 DNA accumulated at higher rates, at least between 3 and 9 h after infection. Thus, the accelerated expression of viral genes in the presence of USP7 corresponds to higher rates of accumulation of viral DNA.

Fig 8.

Viral DNA synthesis in R6702-infected cells. HEp-2 cells were exposed to 5 PFU of either HSV-1(F) or R6702 per cell. Samples were collected at 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 9 h after infection, and total DNA was isolated and used as the template to quantify the amount of viral DNA. Primers for the viral TK were used to identify the viral DNA. Primers for the β-actin gene were used as internal controls for the quantification process. The data represent the fold increase of the viral DNA relative to the DNA of HSV-1(F) present in the cells at 1 h after infection.

The accumulation of viral progeny and spread of R6702 virus from cell to cell in cell cultures.

The purpose of these studies was to determine whether the higher rates of accumulation of viral gene products at early times after infection translates into higher virus yields. The growth curves shown in Fig. 9 were based on infection of HEp-2 cells with 0.2 PFU/cell. Total virus was harvested at the times shown, and the titer was determined on Vero cells. The results shown in Fig. 9A indicate that the yields of virus were virtually identical. In another experiment (not shown), the yield of R6702 was 2-fold higher than that of wild-type virus, a difference unlikely to be significant.

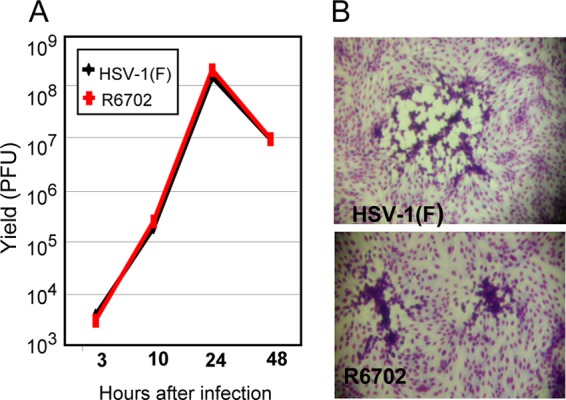

Fig 9.

Growth properties of the R6702 mutant. (A) HEp-2 cells were exposed to 0.2 PFU of either HSV-1(F) or R6702 per cell. Samples were collected at 3 h, 10 h, 24 h, or 48 h after exposure to the viruses, and titrations were done on Vero cells. (B) Viral plaques from previous titrations on Vero cells, stained with Giemsa.

The significant and surprising finding was that the plaques (Fig. 9B) produced by the R6702 recombinant were much smaller and more compact than those produced by the wild-type virus. These observations suggest that the virus produced in R6702-infected cells is not released efficiently or sticks to the surface of the cell in which it is produced and does not spread efficiently from cell to cell.

Total accumulation of REST is not affected in cells depleted of USP7 or overexpressing USP7.

It was reported elsewhere that USP7 counterbalances the ubiquitylation of the REST component of the HDAC1 or -2-CoREST-REST repressor complex and that depletion of USP7 results in reduction of the REST protein level (16). A logical extension of this report is that stabilization of USP7 accelerates the derepression of viral genes affected by the repressor complex and could account for accelerated transcription of viral genes in the R6702 virus-infected cells. To address this hypothesis, two sets of experiments were done. In the first, HEp-2 cells were mock transfected or transfected with irrelevant or USP7 siRNA and then infected with wild-type virus. The results (Fig. 10A) show that REST remained stable throughout the test interval in the absence or the presence of the virus despite the effective depletion of USP7. Consistent with earlier results (4, 8), USP7 was targeted for degradation by the wild-type virus, but not by the R6702 mutant virus (Fig. 10, compare lanes 2 and 8 to lanes 3 and 9).

Fig 10.

Stability of REST in USP7-depleted or USP7-enriched cells. (A) HEp-2 cells were transfected with 100 pmol of either USP7 or control nontarget siRNA for 72 h. The cultures were then exposed to 10 PFU of either HSV-1(F) or R6702 per cell. Samples were collected at 9 h after infection, and approximately 40 μg of total protein was electrophoretically separated on 9% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, electrically transferred to nitrocellulose sheets, and immunoblotted with REST or USP7 antibodies. β-Actin served as a loading control. (B) 293 cells were transfected with a USP7- or mCherry-expressing plasmid. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were exposed to 10 PFU of either HSV-1(F) or R6702 per cell. Samples were analyzed as for panel A.

In the second series of experiments, we tested the effect of USP7 overexpression on the accumulation of REST. For this purpose, 293 cells were transfected with the USP7-expressing plasmid, and at 48 h posttransfection, they were infected with either the wild-type virus or the R6702 mutant. The levels of REST were analyzed in samples collected at 9 h after infection, as described above. Similar analysis was done on untreated cells or on cells transfected with the mCherry-expressing plasmid. Figure 10B shows that the elevated USP7 levels in the transfected cells did not affect the stability of REST.

Overall, these experiments did not reveal any impact of USP7 on the accumulation of REST in the cell lines tested. We found no evidence to support the hypothesis that accelerated accumulation of viral gene products in cells in which USP7 is stable is related to the amounts of REST contained in these cells.

DISCUSSION

The fundamental message of this report is 2-fold. First, it confirms the reports that ICP0 binds USP7 at residue 620, that depletion of USP7 decreases the accumulation of ICP0, and that in turn, USP7 is degraded in an ICP0-dependent manner (1, 4, 8). We also report that, in contrast to the earlier reports (1, 8), overexpression of USP7 accelerated the expression of viral genes. This was done in two ways: by transfecting the gene encoding USP7 or by replacing lysine with isoleucine at residue 620 of ICP0. The recombinant R6702 carrying the amino acid substitution replicated to a level identical to that of the wild-type parent and degraded PML. The down side is that the plaques formed by the R6702 mutant were very small, suggesting that the transmission of virus from cell to cell was impaired. It is noteworthy that proteins encoded by several herpesviruses bind USP7. In the case of Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) (human herpesvirus 8 [HHV-8]), USP7 is recruited by the latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA). A LANA mutant lacking the USP7 binding site enhanced the replication of a plasmid containing the KSHV latent origin of replication but could not be differentiated from wild-type LANA with respect to regulation of viral and cellular promoters (17).

This report raises three issues. Foremost, the question arises as to why the mutants produced by Boutell et al. and Everett et al. (1, 8) and an identical mutant in our laboratory yielded diametrically opposed results. We cannot answer this question except to point out that the procedures for generating amino acid substitutions can introduce additional mutations. The sequence of ICP0 strain 17 differs from that of HSV-1(F). There is the additional problem that the repair of a gene whose phenotype is close to that of the wild-type virus is not a very safe procedure to ensure that the altered phenotype is due to the mutation in the repaired gene.

The second issue raised by both our report and those of Boutell et al and Everett and colleagues (1, 8) is the apparent “fixation” of HSV on USP7. In principle, simple amino acid substitutions could preclude the interaction of a viral protein with a host protein. The fact that ICP0 has evolved a binding site for USP7 suggests that the host protein is “of interest” because it is either beneficial or detrimental to virus replication. ICP0 appears to turn over fairly rapidly at early times after infection with wild-type virus, and the data suggest that in the absence of USP7 it turns over even more rapidly (1, 4, 10). The beneficial effects of sparing ICP0 are not very clear. At least in vitro, the replication of R6702 mutant virus in cells exposed to 0.2 PFU/cell was not impaired. What drove us to investigate USP7 was the question, if the interaction with USP7 is beneficial to the virus, why degrade it? One hypothesis that remains unresolved is that USP7 is in fact deleterious for two reasons: because it accelerates the expression of viral genes, and because it may impair the function of one or more late gene products that affect transmission of virus from cell to cell. Both issues remain to be investigated.

Finally, in principle, the survival of a virus in nature hinges on 3 attributes: maximizing virus yields within a time frame compatible with its ability to block host innate and adaptive responses, efficient transmission from cell to cell and from one individual to the next, and the ability to strike a balance between sustaining itself in its host and not affecting the survival of the host. The detrimental effects of USP7 in curtailing the transmission of virus need no elaboration. Less clear is the effect of accelerating the expression of viral genes. In principle, in the course of their evolution, viruses have developed temporal and spatial niches. The temporal niche reflects a dynamic balance between the many processes that take place in the infected cell to produce an optimal yield of virus. Asynchronous expression of sets of genes early in infection may not meet the required balance of gene products to either produce optimal yields or ensure their dissemination in nature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ryan Hagglund for kindly providing the R6702 virus. We also thank Boudewijn M. T. Burgering, Department of Physiological Chemistry, Centre for Biomedical Genetics, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, for kindly providing the myc-USP7 plasmid and Wei Gu, Columbia University, for Flag-tagged USP7 plasmid.

These studies were aided by National Cancer Institute grant 5R37CA078766.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Boutell C, Canning M, Orr A, Everett RD. 2005. Reciprocal activities between herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP0, a ubiquitin E3 ligase, and ubiquitin-specific protease USP7. J. Virol. 79:12342–12354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boutell C, Everett RD. 2003. The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) regulatory protein ICP0 interacts with and ubiquitinates p53. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36596–36602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boutell C, Everett RD. 2004. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection induces the stabilization of p53 in a USP7- and ATM-independent manner. J. Virol. 78:8068–8077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canning M, Boutell C, Parkinson J, Everett RD. 2004. A RING finger ubiquitin ligase is protected from autocatalyzed ubiquitination and degradation by binding to ubiquitin-specific protease USP7. J. Biol. Chem. 279:38160–38168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chee AV, Lopez P, Pandolfi PP, Roizman B. 2003. Promyelocytic leukemia protein mediates interferon-based anti-herpes simplex virus 1 effects. J. Virol. 77:7101–7105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chee AV, Roizman B. 2004. Herpes simplex virus 1 gene products occlude the interferon signaling pathway at multiple sites. J. Virol. 78:4185–4196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ejercito PM, Kieff ED, Roizman B. 1968. Characterization of herpes simplex virus strains differing in their effects on social behaviour of infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2:357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Everett RD, Meredith M, Orr A. 1999. The ability of herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein Vmw110 to bind to a ubiquitin-specific protease contributes to its roles in the activation of gene expression and stimulation of virus replication. J. Virol. 73:417–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gu H, Liang Y, Mandel G, Roizman B. 2005. Components of the REST/CoREST/histone deacetylase repressor complex are disrupted, modified, and translocated in HSV-1-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:7571–7576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gu H, Poon AP, Roizman B. 2009. During its nuclear phase the multifunctional regulatory protein ICP0 undergoes proteolytic cleavage characteristic of polyproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:19132–19137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gu H, Roizman B. 2003. The degradation of promyelocytic leukemia and Sp100 proteins by herpes simplex virus 1 is mediated by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UbcH5a. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:8963–8968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gu H, Roizman B. 2007. Herpes simplex virus-infected cell protein 0 blocks the silencing of viral DNA by dissociating histone deacetylases from the CoREST-REST complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:17134–17139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gu H, Roizman B. 2009. The two functions of herpes simplex virus 1 ICP0, inhibition of silencing by the CoREST/REST/HDAC complex and degradation of PML, are executed in tandem. J. Virol. 83:181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hagglund R, Roizman B. 2004. Role of ICP0 in the strategy of conquest of the host cell by herpes simplex virus 1. J. Virol. 78:2169–2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hagglund R, Van Sant C, Lopez P, Roizman B. 2002. Herpes simplex virus 1-infected cell protein 0 contains two E3 ubiquitin ligase sites specific for different E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:631–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang Z, et al. 2011. Deubiquitylase HAUSP stabilizes REST and promotes maintenance of neural progenitor cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:142–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jager W, et al. 2012. The ubiquitin-specific protease USP7 modulates the replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent episomal DNA. J. Virol. 86:6745–6757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kalamvoki M, Roizman B. 2008. Nuclear retention of ICP0 in cells exposed to HDAC inhibitor or transfected with DNA before infection with herpes simplex virus 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:20488–20493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kalamvoki M, Roizman B. 2009. ICP0 enables and monitors the function of D cyclins in herpes simplex virus 1 infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:14576–14580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalamvoki M, Roizman B. 2010. Circadian CLOCK histone acetyl transferase localizes at ND10 nuclear bodies and enables herpes simplex virus gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:17721–17726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kalamvoki M, Roizman B. 2010. Interwoven roles of cyclin D3 and cdk4 recruited by ICP0 and ICP4 in the expression of herpes simplex virus genes. J. Virol. 84:9709–9717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kalamvoki M, Roizman B. 2011. The histone acetyltransferase CLOCK is an essential component of the herpes simplex virus 1 transcriptome that includes TFIID, ICP4, ICP27, and ICP22. J. Virol. 85:9472–9477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kawaguchi Y, Van Sant C, Roizman B. 1997. Herpes simplex virus 1 alpha regulatory protein ICP0 interacts with and stabilizes the cell cycle regulator cyclin D3. J. Virol. 71:7328–7336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lium EK, Silverstein S. 1997. Mutational analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 C3HC4 zinc ring finger reveals a requirement for ICP0 in the expression of the essential alpha27 gene. J. Virol. 71:8602–8614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roizman B. 2011. The checkpoints of viral gene expression in productive and latent infection: the role of the HDAC/CoREST/LSD1/REST repressor complex. J. Virol. 85:7474–7482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roizman B, Gu H, Mandel G. 2005. The first 30 minutes in the life of a virus: unREST in the nucleus. Cell Cycle 4:1019–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sarkari F, Wang X, Nguyen T, Frappier L. 2011. The herpesvirus associated ubiquitin specific protease, USP7, is a negative regulator of PML proteins and PML nuclear bodies. PLoS One 6:e16598 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van Sant C, Kawaguchi Y, Roizman B. 1999. A single amino acid substitution in the cyclin D binding domain of the infected cell protein no. 0 abrogates the neuroinvasiveness of herpes simplex virus without affecting its ability to replicate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:8184–8189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]