Abstract

Expression of a retroviral Gag protein in mammalian cells leads to the assembly of virus particles. In vitro, recombinant Gag proteins are soluble but assemble into virus-like particles (VLPs) upon addition of nucleic acid. We have proposed that Gag undergoes a conformational change when it is at a high local concentration and that this change is an essential prerequisite for particle assembly; perhaps one way that this condition can be fulfilled is by the cooperative binding of Gag molecules to nucleic acid. We have now characterized the assembly in human cells of HIV-1 Gag molecules with a variety of defects, including (i) inability to bind to the plasma membrane, (ii) near-total inability of their capsid domains to engage in dimeric interaction, and (iii) drastically compromised ability to bind RNA. We find that Gag molecules with any one of these defects still retain some ability to assemble into roughly spherical objects with roughly correct radius of curvature. However, combination of any two of the defects completely destroys this capability. The results suggest that these three functions are somewhat redundant with respect to their contribution to particle assembly. We suggest that they are alternative mechanisms for the initial concentration of Gag molecules; under our experimental conditions, any two of the three is sufficient to lead to some semblance of correct assembly.

INTRODUCTION

Assembly of retroviral particles is mediated by the Gag protein, and expression of this protein in mammalian cells is sufficient for efficient assembly of virus particles in vivo. The molecular mechanisms in particle assembly have also been investigated in purified systems, using recombinant Gag proteins. These studies show that the presence of nucleic acid (NA) is required for Gag to assemble in vitro (4–6, 17).

The reason for this NA requirement is not clear. However, chimeric proteins in which the nucleocapsid (NC) domain (the primary RNA-binding domain of the Gag protein) is replaced with a leucine-zipper dimerization domain assemble efficiently in mammalian cells (1, 8, 19, 35). The resulting particles are morphologically almost indistinguishable from authentic immature particles but contain very little, if any, RNA (8). These observations raise the possibility that cooperative binding of Gag to NA is a way of juxtaposing Gag molecules and that this initial juxtaposition or oligomerization primes them for assembly (19, 22, 23). Based in part on these observations, we have recently suggested that oligomerization of Gag is an essential first step in particle assembly. More specifically, we also proposed that the SP1 region of HIV-1 Gag (lying between the NC domain and the capsid [CA] domain) undergoes a conformational change when Gag is at a high local concentration and that this change could lead to the exposure of new interfaces in the CA domain (11). These interfaces might participate in the Gag-Gag interactions involved in particle formation.

Is NA required for assembly in vivo as it is in vitro? It has been reported that HIV-1 Gag lacking its NC domain can still assemble in mammalian cells (26), but it is not known whether this protein can still bind RNA, perhaps via its matrix (MA) domain (7, 21, 27, 30). Alternatively, it is possible that assembly in vivo does not require RNA; perhaps other mechanisms can also fulfill the suggested requirement for a high local Gag concentration preceding particle assembly. The present work explores these possibilities. Our analysis of single and double mutants of HIV-1 Gag protein is consistent with the idea that correct particle assembly requires oligomerization of Gag but that there are several mechanisms for promoting this oligomerization within the cell: our analysis indicates that these mechanisms are, at least in part, redundant with each other, with respect to virus particle assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

A plasmid expressing HIV-1 Gag independently of Rev (pCMV55M1-10) was the basis for all HIV-1 constructs used in this study (33). A derivative of this plasmid lacking the entire NC coding region was constructed by inverse PCR. The primers used for this construction were 5′-Phos-TTTTTAGGGAAGATCTGGCCTTCCTACAAGGG and 5′-Phos-CATTATGGTAGCTGAATTTGTTACTTGGCTC. Mutageneses were performed using the QuikChange kit from Stratagene.

Transfections and virus collection.

293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as described previously (24). Cells were transfected with Trans-IT-293 transfection reagent (Mirus). The plasmid pBluescript KS+ was used for mock transfections. DNA was removed 24 h posttransfection, and virus-containing supernatants were collected 72 h posttransfection. Virus-like particles (VLPs) were collected by centrifuging the supernatants through a 20% sucrose (wt/vol) cushion with a SW-28 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 112,000 × g and 4°C for 1 h.

Immunoblotting.

After centrifugation, pellets containing VLPs were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. Cells were resuspended in NuPAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Invitrogen) and lysed by sonication (0.7 s on/2.0 s off for 4 min). Goat anti-p24CA antibody (diluted 1:10,000) was used to detect HIV-1 Gag (kind gift from D. Ott, AIDS and Cancer Virus Program, SAIC-Frederick). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (BioChain) was used as secondary antibody (diluted at 1:10,000). The cellular β-actin protein was detected using a monoclonal antibody produced in mouse (diluted 1:5000; Sigma-Aldrich).

Near-infrared quantitative Western blotting was performed using LI-COR Biosciences reagents as recommended by the manufacturer. IRDye 800CW donkey anti-goat (1:20,000) and IRDye 680LT donkey anti-mouse (1:10,000) were used as secondary antibodies. The Odyssey Imaging system was used to detect and quantify protein bands (LI-COR Biosciences).

Electron microscopy.

Cells were prepared for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) as described previously (24).

Viral and cellular RNA isolation.

RNA was isolated from VLP pellets by proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction as described previously (32), as well as from VLP pellets treated with nucleases and subtilisin to reduce contamination by nucleic acids and microvesicles that often copellet with VLPs (a method adapted from Ott et al. [28]). Specifically, following centrifugation of culture supernatants through a 20% sucrose cushion, pellets containing VLPs were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer containing 100 mM NaCl/4 mM MgCl2 and treated with DNase I (10U/ml supernatant; Fermentas) and RNase cocktail (10 U/ml supernatant; Ambion) for 1.5 h at 37°C. Nuclease activity was quenched by the addition of 20 mM EDTA, and samples were centrifuged again through a 20% sucrose cushion using a SW-41 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 234,000 × g and 4°C for 1 h. The resulting pellets were treated with subtilisin A (1 mg/ml in 20mMTris [pH 8.0], 1 mMMgCl2; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 15 h. Subtilisin was inactivated by the addition of 250 μg/ml phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich), and reaction samples were centrifuged once more through a 20% sucrose cushion to pellet VLPs. This centrifugation step was performed with a SW-55 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 303,000 × g and 4°C for 2 h. The resulting pellets are soft and easily dislodged during removal of the supernatant. Nuclease- and subtilisin-treated pellets were then lysed with an SDS- and proteinase K-containing buffer, and RNA from VLPs was isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction as described previously (32). Viral RNA was quantified using the Ribogreen assay (Quant-iT Ribogreen RNA reagent and kit; Invitrogen).

Cellular RNA was isolated using the Ribopure kit from Ambion according to manufacturer's instructions and quantified by measuring absorbance at 260 nm.

qRT-PCR.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out using the TaqMan RNA-to-CT 1-step kit (Applied Biosystems). Primers and probes, as well as RNA preparation for 18S RNA, 7SL Alu domain, ASB-1, PLEKHB-2, and PGK-1, were as reported by Crist et al. (8). The S domain of the 7SL RNA was detected using the following primers and probe: 5′-TTCGGCATCAATATGGTGACCTCC-3′ (forward primer), 5′-GATCAGCACGGGAGTTTTGACC-3′ (reverse primer), and 5′-FAM-AGGTCGGAAACGGAGCAGGTCA-TAMRA-3′ (probe).

RESULTS

As discussed above, we have suggested (11) that HIV-1 virus assembly might be triggered by a high local concentration of Gag molecules. At least three mechanisms might contribute to raising the local Gag concentration within the cell to levels sufficient for assembly: first, cooperative binding to RNA, as noted above; second, binding of Gag to the plasma membrane, in essence reducing the space available to Gag from three to two dimensions; and third, direct Gag-Gag association via the dimer interface within the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the CA domain of Gag (12, 15).

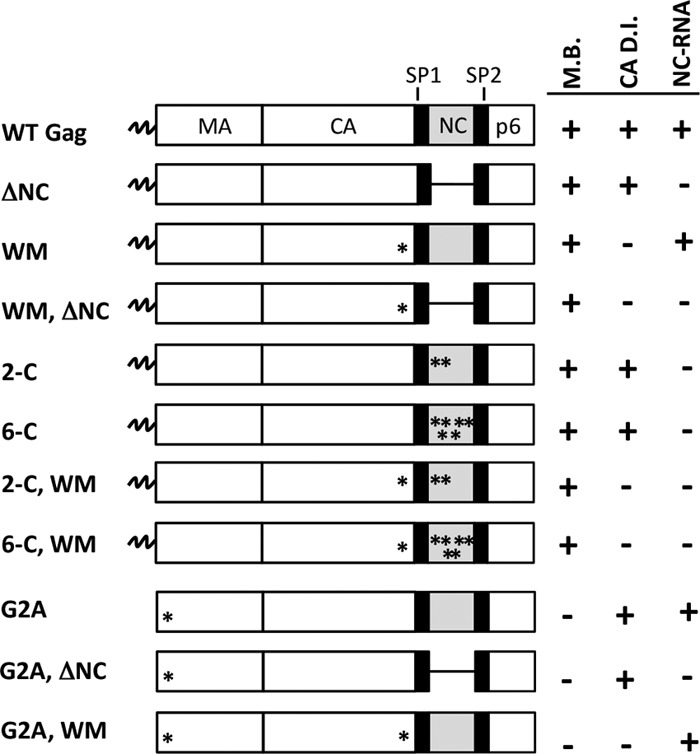

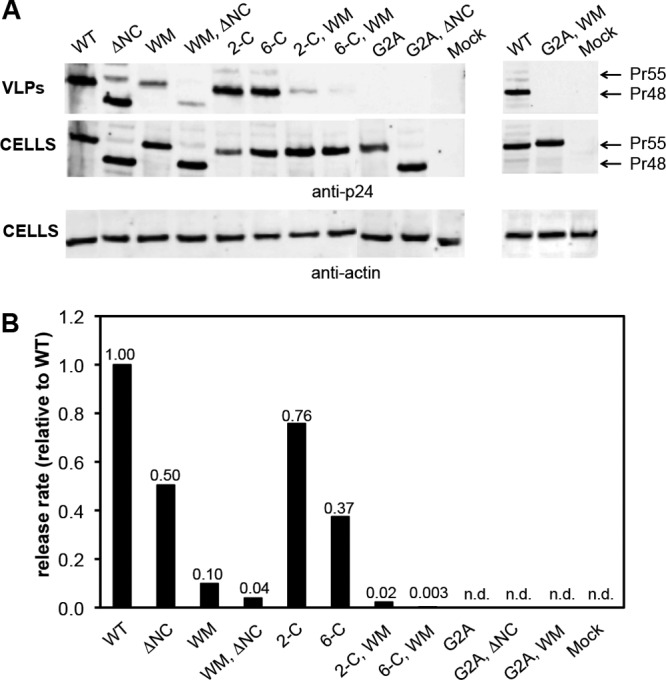

To test the role of each of these factors in virus-like particle (VLP) production, we transiently transfected 293T cells with a plasmid expressing HIV-1 Gag containing mutations affecting each of these functions. The mutants are presented schematically in Fig. 1. VLP production was assessed by immunoblotting with anti-p24CA antiserum (see Fig. 2A and B). Assembly efficiency was quantitated as the VLP release rate, i.e., the ratio of Gag in VLPs to Gag in cell lysates, with the cellular value in turn normalized to the actin loading control.

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of mutants used to study HIV-1 assembly in vivo. ΔNC represents deletion of the entire NC domain. WM represents the W316A, M317A double mutant in CACTD. Asterisks denote the amino acid substitution(s) described on the left of each diagram. 2-C and 6-C refer to C392,395S and C392,395,405,413,416,426S, respectively. On the right of each diagram, the presence of an intact domain is represented by a (+) and mutations in that domain are represented by a (−). M.B., membrane binding; CA D.I., CA dimer interface; NC-RNA, region of NC-RNA interactions.

Fig 2.

HIV-1 viral particles released from Gag mutants. (A) Western blot analysis comparing Gag expression and VLP production by wild-type (WT) Gag and mutants. Equal amounts of supernatant (equivalent to 10 μl unconcentrated culture fluid) and cells were loaded for each sample. Bound fluorescent secondary antibodies were visualized using the near-infrared Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR). Top two panels depict the release of pelletable Gag (Pr55; Pr48 for the ΔNC mutant) and the intracellular level of Gag using anti-p24CA antiserum. Bottom panel depicts the intracellular level of β-actin. (B) The protein detected in panel A was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. The VLP release rate was calculated as the ratio of Gag detected in VLPs to Gag detected in cells, normalized to intracellular actin levels. Release rate is shown relative to WT. No signal was detected in the supernatants of mock and G2A mutants (n.d.); the release rate in these cultures was ≤0.002 relative to WT. Data shown represent one of 2 or 3 independent transfections.

Binding of Gag to RNA is presumably mediated by the nucleocapsid (NC) domain, with a major contribution from the two zinc fingers within this domain (9, 14). Therefore, we assessed the role of RNA-binding in assembly in vivo using mutants in which zinc-coordinating cysteines were replaced with serines or in which the entire NC domain was deleted. As shown in Fig. 2, the replacement of either the first two or all six cysteines only reduced the VLP release rate from 1.5- to 3-fold; in fact, the deletion of NC had a similar effect.

The effect of ablating the dimer interface in the CA domain, by changing CA Trp184 and Met185 (i.e., residues 316 and 317 of Gag, counting from the initiator methionine) to alanines (called the WM mutant) (12), is also shown in Fig. 2. This mutation reduces the particle release rate by approximately 10-fold. Finally, the ability of Gag to bind to the plasma membrane was destroyed by replacing the N-terminal glycine residue, the site of the myristate modification on HIV-1 Gag, with alanine. This change completely prevents the release of detectable levels of VLPs (Fig. 2) (3, 16, 31).

It seemed possible that the three elements tested here might cooperate with each other to produce high local Gag concentrations within the cell. To explore this possibility, we also tested combinations of the mutations discussed above for their ability to assemble and release particles. The results are also presented in Fig. 2. We found that combining the WM mutation with the cysteine mutations or the NC deletion had a drastic effect on the release rate, yielding reductions of ∼25- to 300-fold. This apparent synergy between the dimer interface and RNA-binding elements of Gag suggests that they might play a somewhat redundant role with respect to particle assembly. Not surprisingly, all combinations that included the myristylation-negative G2A mutant failed to release detectable levels of VLPs.

Several reports in the literature raise the possibility that Gag can bind RNA via its MA domain, as well as its NC domain (7, 21, 30). It was therefore of interest to determine whether RNA was present in the VLPs formed by the ΔNC Gag mutant protein. Figure 3A shows that, under our experimental conditions (transient transfection of 293T cells with a Gag expression plasmid in which the coding region contains silent mutations rendering it Rev independent), the ΔNC Gag mutant protein produces VLPs at roughly the same level as the wild-type (WT) control. When these VLP pellets were assayed, using the Ribogreen assay, for their total RNA content (Fig. 3B), they were found to contain very little RNA, although they contained nearly the same amount of Gag protein as the control. We estimate that the pellets contain ∼1/10 as much RNA as the wild-type control pellets.

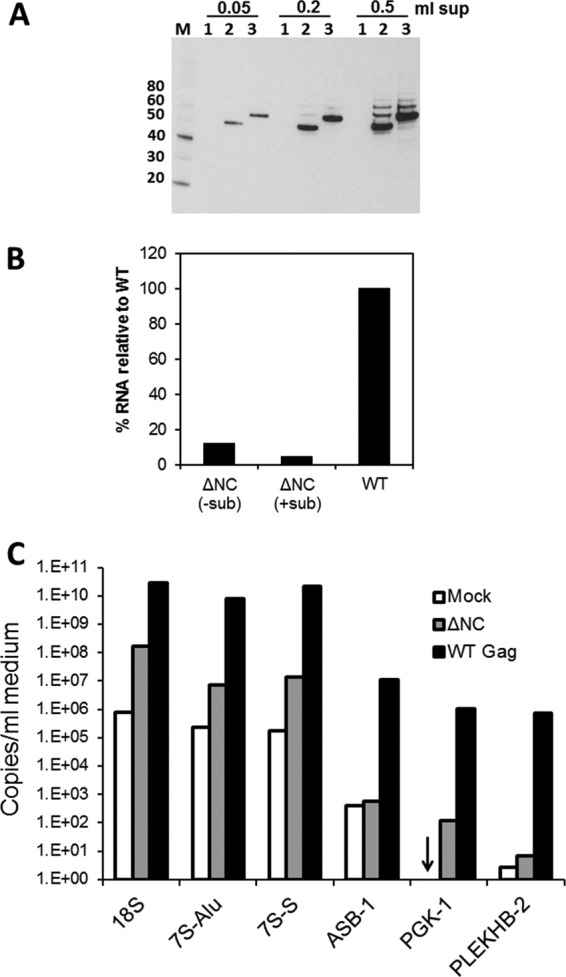

Fig 3.

HIV-1 viral particles released in the absence of NC contain very little RNA. (A) Western blot analysis with anti-p24CA antibody. M, MagicMark XP marker with weights in kDa indicated on the left; 1, mock; 2, the ΔNC Gag mutant; 3, wild-type Gag. The volume of culture fluid pelleted and loaded in each lane is indicated above the blot. Bound, horseradish peroxidase-tagged secondary antibodies were visualized by chemiluminescence. (B) RNA was isolated from particles containing similar amounts of Gag (as judged by Western blot analysis) and assayed for RNA content using the Ribogreen assay. Pellets of the HIV-1 ΔNC mutant particles that were not treated with nucleases and subtilisin (−sub) contained ∼12.4% RNA compared to WT Gag. Particles that were treated with nucleases and subtilisin prior to lysis and RNA isolation (+sub) contained ∼4.5% RNA compared to WT Gag. Mock values were subtracted from both the ΔNC mutant and WT values to obtain percentage results. (C) qRT-PCR was performed to measure copies of 18S rRNA, 7SL RNA, and mRNA species. A representative panel is shown from assays performed on RNA isolated from one of seven independent transfections (VLPs were not treated with subtilisin in this example). Both the Alu (7S-Alu) and the S domain (7S-S) of 7SL RNA were probed. Arrow indicates the presence of <10 copies (the detection limit for PGK-1 was 10 copies while that for PLEKHB-2 was 1 copy).

It is also known that cellular debris can be present in these pellets (25); to eliminate these possible contaminants, we also treated the solubilized pellets with subtilisin (25) and with RNase and DNase. This digestion, which should remove RNAs that are not protected within intact virions, reduced the level of RNA in the pellets to only ∼4 to 5% of the amount present in the similarly treated wild-type pellets (Fig. 3B). Thus, little, if any, RNA is evidently packaged in the VLPs formed by the ΔNC Gag mutant.

As a further test of the presence of RNA in ΔNC VLPs, we used real-time reverse transcription-PCR to assay for specific RNA species. These RNAs are known to be packaged in VLPs formed by wild-type Gag in the absence of genomic RNA (32). The extent to which VLP pellets are contaminated by RNAs not contained in VLPs was estimated by characterizing RNAs in pellets obtained from cultures transfected with empty plasmid (mock pellets). A representative experiment from seven different transfections is shown in Fig. 3C. We found that the copy numbers of cellular mRNAs in ΔNC and mock particles were similar to each other and always 2 to 4 orders of magnitude lower than the copy numbers in WT Gag particles. As expected, the copy numbers of the mRNA species within the cells were not affected by the transfection of the plasmids (data not shown). The encapsidation efficiency of these mRNAs, i.e., copies/ng RNA in VLPs normalized to copies/ng RNA in cells, did not reveal significant selectivity of the three mRNAs in ΔNC particles (data not shown). These results, and particularly the similarity of values in mock and ΔNC particles, indicate that cellular mRNAs do not represent a significant proportion of the small amounts of RNA present in ΔNC particles.

The lack of cellular mRNAs in ΔNC particles prompted an examination for rRNA, which is the most abundant RNA in the cell, and 7SL RNA, which is known to be packaged in retrovirus particles (2, 20, 32). We found that 18S rRNA was present at 10- to 100-fold higher levels in preparations of wild-type particles than in either mock or ΔNC particles. Mock and ΔNC levels of 18S rRNA were inconsistent: copy numbers were comparable in some experiments, but ΔNC levels were 10- to 100-fold higher than mock in others (Fig. 3C and data not shown). A fragment of 7SL RNA, which encompasses a large portion of the S domain, has been recently reported in ΔNC particles (18). We therefore evaluated the presence of both the Alu and S domains of the 7SL RNA. We found that the Alu and the S domain of 7SL RNA are present at higher levels in ΔNC particles than in mock pellets, but not nearly as high as in wild-type particles. Unlike Keene et al. (20), we did not find that the S domain of 7SL RNA was present at higher levels in ΔNC particles than the Alu domain. We do not know why the amounts of rRNA and 7SL RNA were higher than those in mock pellets in some, but not all, experiments.

Overall, these results demonstrate that Gag lacking NC can form VLPs and that very little total RNA is present in these particles. Thus, HIV-1 is apparently not totally dependent on RNA for particle formation.

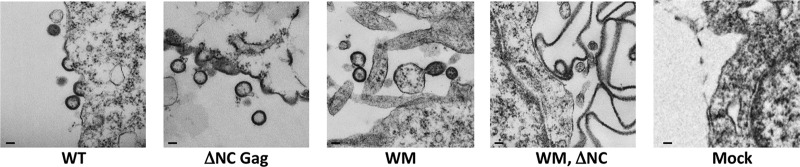

To further explore the roles of plasma membrane association, direct dimerization, and RNA-binding in particle assembly, we also examined the cells expressing mutant Gag proteins by transmission electron microscopy. Figure 4 shows representative images of cells containing the ΔNC Gag mutant, the WM Gag mutant, or the WM ΔNC Gag double mutant. Many nearly normal-looking VLPs are present in cells expressing the ΔNC Gag mutant, as originally reported by Ott et al. (26). The structures formed by the WM Gag mutant are considerably more heterogeneous than those formed by wild-type Gag or the ΔNC Gag mutant but include some particles that are roughly spherical with approximately the correct radius of curvature (12). In contrast, when the Gag protein lacks both the dimer interface and its NC domain, no virus-like structures are visible in or near the cells. Rather, the cells contain large sheets and “balloons” of material (noting, of course, that these images show two-dimensional sections of three-dimensional objects). It thus appears that the ability to assemble into particles with the characteristic radius of curvature depends upon the presence of either the dimer interface or the NC domain in the Gag protein.

Fig 4.

TEM images of 293T cells transfected with plasmids bearing mutations in the NC and CACTD regions of HIV-1 Gag. Cells were fixed 72 h posttransfection. Scale bar is equivalent to 100 nm.

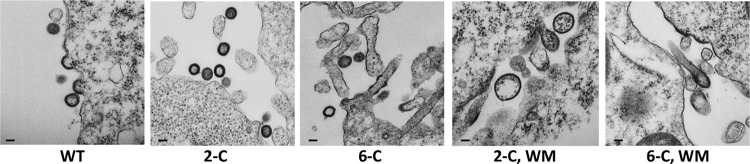

Figure 5 presents a similar analysis in which the NC domain is not completely deleted, but two or all six cysteine residues in the zinc fingers are replaced with serines. Again, the proteins with the mutant NC domains form nearly normal-looking VLPs, but when these defects are combined with the WM mutation, the structures formed are far more heterogeneous and irregularly shaped than with either mutation alone, with abundant balloons.

Fig 5.

TEM images of 293T cells transfected with plasmids bearing mutations in the Zn-finger and CACTD regions of HIV-1 Gag. Cells were fixed 72 h posttransfection. Scale bar is equivalent to 100 nm.

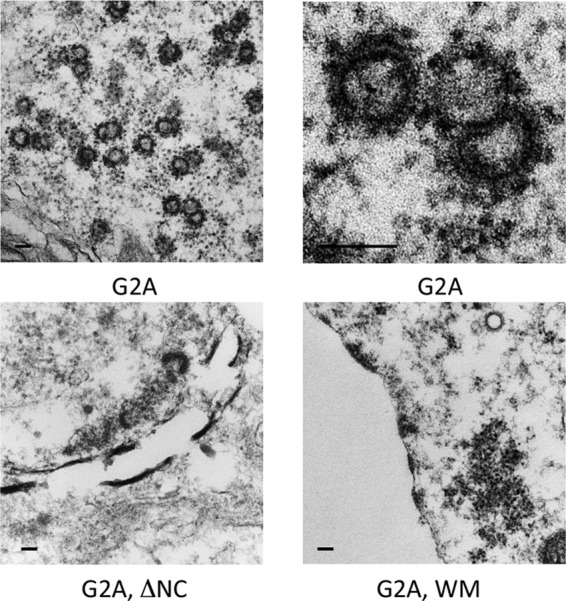

We also examined cells expressing the G2A Gag, G2A WM Gag, or G2A ΔNC Gag mutant. We have previously reported that many structures resembling virus particles are present in the cytoplasm of cells expressing the G2A Gag mutant. These structures are approximately the same radius of curvature as authentic virions, although many are incomplete (11). Images of these particles at two different magnifications are shown in Fig. 6. It is clear that, under our experimental conditions, the Gag protein does not need to associate with the plasma membrane in order to assemble in a nearly correct fashion. However, these intracellular structures are not seen when the G2A mutation is combined with either the WM mutation or the ΔNC deletion. Representative images are shown in Fig. 6. While there are darkly stained sheets and intracellular aggregates, there are no structures with the radius of curvature typical of virus particles. The implications of these observations are considered below.

Fig 6.

TEM images of 293T cells transfected with plasmids bearing mutations in the MA, NC, and CACTD regions of HIV-1 Gag. Cells were fixed 72 h posttransfection. Scale bar is equivalent to 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

We have previously suggested that accumulation of HIV-1 Gag to a high local concentration, and/or oligomerization of Gag, is a prerequisite for its assembly into virus-like particles. Specifically, we found that the conformation of SP1, a short spacer between the CA and NC domains, depends upon its concentration. We proposed that at a high local Gag concentration, this change could occur and be propagated into the CA domain, exposing or activating new interfaces for Gag-Gag interaction, leading to particle assembly (11).

We now report that three elements within Gag are functionally redundant with respect to particle assembly. That is, ablation of any one of these elements spared, at least partially, the ability of Gag to assemble within human cells into roughly spherical objects with radius of curvature similar to that of authentic, wild-type virus particles. In contrast, Gag molecules bearing defects in any two of these elements were apparently totally unable to assemble with any regular curvature (Fig. 4 to 6). The three elements are the myristylation site at the N terminus of Gag, the dimer interface within the C-terminal domain of the CA domain, and the RNA-binding residues within the NC domain. The latter defects included not only mutation of the zinc-coordinating cysteine residues but also deletion of the entire NC domain.

The redundancy of these three elements implies that they all contribute to assembly through some common function or pathway. One obvious possibility is that they all promote the initial oligomerization of Gag, leading to its assembly into particles. Thus, myristylation presumably leads to concentration of Gag on the plasma membrane, RNA-binding is presumably cooperative so that Gag molecules bound to an RNA will be in close proximity, and interactions of Gag molecules via the C-terminal regions of their CA domains lead directly to dimerization (12, 15). We would suggest that, when one of these elements is removed, the association between Gag molecules is still strong enough to permit formation of spheres (or partially spherical structures) with the correct radius of curvature. The redundant relationship between them was also suggested by quantitative measurements of the release from the cells of Gag protein in large, pelletable structures (Fig. 2B); however, these measurements cannot distinguish between Gag protein in structures with the shape of virus particles and Gag protein in amorphous aggregates. Moreover, the mutant Gag proteins lacking the N-terminal myristylation site are not released from the cells and so are not amenable to this experimental approach.

Other explanations of our results are, of course, possible. For example, we have reported that HIV-1 Gag assumes a compact conformation when bound to either nucleic acid or membrane but extends to a rod-like conformation in the presence of both of these ligands (10). One might then imagine that, in vivo, Gag molecules must interact with each other at a minimum of two points in order to successfully assemble as extended rods, rather than folded molecules (4, 5, 10). This alternative hypothesis is also completely consistent with the data presented here. Gag interactions with cellular factors could also affect these observations; specifically, the NC domain has also been reported to participate in interactions with cellular proteins leading to release of assembled virions from the host cell (13, 29).

Our finding of relatively efficient assembly of immature viral particles in vivo by the ΔNC Gag mutant confirms the prior report of Ott et al. (26). It was of considerable interest to know whether this represents RNA-independent assembly or whether other regions of Gag can also bind RNA and thus substitute for NC in RNA-dependent assembly. We found that the ΔNC mutant particles contain ∼10% or less of the amount of RNA present in wild-type particles (Fig. 3B). We also tested for 18S rRNA, 7SL RNA, and several mRNA species known to be encapsidated by wild-type Gag if no RNA containing a packaging signal is present in the cells (32). However, none of these RNAs was present in the ΔNC mutant particles at significant levels (Fig. 3C). Thus, the results strongly suggest that the deleted Gag protein assembles in vivo without RNA. We cannot exclude the possibility, however, that the ΔNC mutant particles contain a low level of some RNA species not tested here; notably, we did not assay for tRNA, one of the major types of RNA within the cell.

It should be noted that other groups have also examined the RNA content of the ΔNC mutant particles. Ott et al. observed a 2-fold reduction of total RNA in the absence of NC (compared to ≥10-fold in our study) (27). Keene et al. found that a fragment of 7SL RNA is enriched in ΔNC particles, but this was not the case in our experiments (20). These discrepancies may be a result of the use of different expression systems and experimental procedures.

Functional redundancy in HIV-1 assembly has also been observed by other investigators. Ott et al. reported that, while either NC deletion or mutations in the highly basic region of MA are almost inconsequential for assembly, a combination of the two defects abolishes it (27). Hogue et al. analyzed Gag-Gag interactions in vivo using fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy and found that membrane binding and NC-RNA interactions can functionally compensate each other (18). Our examination of viral particles produced by a wide selection of mutants complements these studies and contributes to a more comprehensive analysis of the assembly process.

It is important to realize that our studies have been performed using transient transfection with Rev-independent Gag (33). This is a Gag gene with a number of silent mutations, enabling its expression in the absence of the viral Rev protein; it can be considered a codon-optimized Gag. Its expression is driven by a cytomegalovirus promoter. For all these reasons, the level of Gag expression in our experiments is significantly higher than in naturally infected cells. As virus particle assembly is enhanced at high Gag concentrations (34), the results we obtained may not represent what would occur under natural infection conditions. Nevertheless, these experiments show us the assembly capabilities of the mutant Gag proteins and thus help illuminate molecular mechanisms in assembly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, in part by the NIH Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program, and in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN26120080001E.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

We thank Robert Gorelick and David Ott for many helpful discussions and providing a protocol for the treatment of virus-containing pellets with subtilisin.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Accola MA, Strack B, Gottlinger HG. 2000. Efficient particle production by minimal Gag constructs which retain the carboxy-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid-p2 and a late assembly domain. J. Virol. 74:5395–5402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bishop JM, et al. 1970. The low molecular weight RNAs of Rous sarcoma virus. II. The 7 S RNA. Virology 42:927–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bryant M, Ratner L. 1990. Myristoylation-dependent replication and assembly of human immunodeficiency virus 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:523–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campbell S, et al. 2001. Modulation of HIV-like particle assembly in vitro by inositol phosphates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:10875–10879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell S, Rein A. 1999. In vitro assembly properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein lacking the p6 domain. J. Virol. 73:2270–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campbell S, Vogt VM. 1995. Self-assembly in vitro of purified CA-NC proteins from Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 69:6487–6497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chukkapalli V, Oh SJ, Ono A. 2010. Opposing mechanisms involving RNA and lipids regulate HIV-1 Gag membrane binding through the highly basic region of the matrix domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:1600–1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crist RM, et al. 2009. Assembly properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag-leucine zipper chimeras: implications for retrovirus assembly. J. Virol. 83:2216–2225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Darlix JL, Lapadat-Tapolsky M, de Rocquigny H, Roques BP. 1995. First glimpses at structure-function relationships of the nucleocapsid protein of retroviruses. J. Mol. Biol. 254:523–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Datta SA, et al. 2011. HIV-1 Gag extension: conformational changes require simultaneous interaction with membrane and nucleic acid. J. Mol. Biol. 406:205–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Datta SA, et al. 2011. On the role of the SP1 domain in HIV-1 particle assembly: a molecular switch? J. Virol. 85:4111–4121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Datta SA, et al. 2007. Interactions between HIV-1 Gag molecules in solution: an inositol phosphate-mediated switch. J. Mol. Biol. 365:799–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dussupt V, et al. 2009. The nucleocapsid region of HIV-1 Gag cooperates with the PTAP and LYPXnL late domains to recruit the cellular machinery necessary for viral budding. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000339 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fisher RJ, et al. 2006. Complex interactions of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein with oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:472–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gamble TR, et al. 1997. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 278:849–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gottlinger HG, Sodroski JG, Haseltine WA. 1989. Role of capsid precursor processing and myristoylation in morphogenesis and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5781–5785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gross I, et al. 2000. A conformational switch controlling HIV-1 morphogenesis. EMBO J. 19:103–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hogue IB, Hoppe A, Ono A. 2009. Quantitative fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag-Gag interaction: relative contributions of the CA and NC domains and membrane binding. J. Virol. 83:7322–7336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson MC, Scobie HM, Ma YM, Vogt VM. 2002. Nucleic acid-independent retrovirus assembly can be driven by dimerization. J. Virol. 76:11177–11185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keene SE, King SR, Telesnitsky A. 2010. 7SL RNA is retained in HIV-1 minimal virus-like particles as an S-domain fragment. J. Virol. 84:9070–9077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lochrie MA, et al. 1997. In vitro selection of RNAs that bind to the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 gag polyprotein. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2902–2910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma YM, Vogt VM. 2004. Nucleic acid binding-induced Gag dimerization in the assembly of Rous sarcoma virus particles in vitro. J. Virol. 78:52–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ma YM, Vogt VM. 2002. Rous sarcoma virus Gag protein-oligonucleotide interaction suggests a critical role for protein dimer formation in assembly. J. Virol. 76:5452–5462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muriaux D, et al. 2004. Role of murine leukemia virus nucleocapsid protein in virus assembly. J. Virol. 78:12378–12385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ott DE. 2009. Purification of HIV-1 virions by subtilisin digestion or CD45 immunoaffinity depletion for biochemical studies. Methods Mol. Biol. 485:15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ott DE, et al. 2003. Elimination of protease activity restores efficient virion production to a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid deletion mutant. J. Virol. 77:5547–5556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ott DE, Coren LV, Gagliardi TD. 2005. Redundant roles for nucleocapsid and matrix RNA-binding sequences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly. J. Virol. 79:13839–13847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ott DE, et al. 1996. Cytoskeletal proteins inside human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions. J. Virol. 70:7734–7743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Popov S, Popova E, Inoue M, Gottlinger HG. 2008. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag engages the Bro1 domain of ALIX/AIP1 through the nucleocapsid. J. Virol. 82:1389–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Purohit P, Dupont S, Stevenson M, Green MR. 2001. Sequence-specific interaction between HIV-1 matrix protein and viral genomic RNA revealed by in vitro genetic selection. RNA 7:576–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rein A, McClure MR, Rice NR, Luftig RB, Schultz AM. 1986. Myristylation site in Pr65gag is essential for virus particle formation by Moloney murine leukemia virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:7246–7250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rulli SJ, Jr, et al. 2007. Selective and nonselective packaging of cellular RNAs in retrovirus particles. J. Virol. 81:6623–6631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schneider R, Campbell M, Nasioulas G, Felber BK, Pavlakis GN. 1997. Inactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibitory elements allows Rev.-independent expression of Gag and Gag/protease and particle formation. J. Virol. 71:4892–4903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yadav SS, Wilson SJ, Bieniasz PD. 2012. A facile quantitative assay for viral particle genesis reveals cooperativity in virion assembly and saturation of an antiviral protein. Virology 429:155–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang Y, Qian H, Love Z, Barklis E. 1998. Analysis of the assembly function of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag protein nucleocapsid domain. J. Virol. 72:1782–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]