Abstract

Our long-term goal is to identify and characterize molecular mechanisms regulating tooth development, including those mediating the critical dental epithelial-dental mesenchymal (DE-DM) cell interactions required for normal tooth development. The goal of this study was to investigate Chemerin (Rarres2)/ChemR23(Cmklr1) signaling in DE-DM cell interactions in normal tooth development. Here we present, for the first time, tissue-specific expression patterns of Chemerin and ChemR23 in mouse tooth development. We show that Chemerin is expressed in cultured DE progenitor cells, while ChemR23 is expressed in cultured DM cells. Moreover, we demonstrate that ribosomal protein S6 (rS6) and Akt, downstream targets of Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling, are phosphorylated in response to Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling in vitro and are expressed in mouse tooth development. Together, these results suggest roles for Chemerin/ChemR23-mediated DE-DM cell signaling during tooth morphogenesis.

Keywords: ribosomal protein S6, cell-cell interaction, dental epithelium, dental mesenchyme, tooth differentiation, cell interactions

Introduction

A thorough understanding of molecular signaling events during normal tooth development can inform future dental therapies. In this report, we present the expression patterns and functional characterizations of the ligand Chemerin, recently renamed retinoic acid receptor responder (Rarres2), and its G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) ChemR23, recently renamed Chemokine-like receptor 1 (Cmklr1), in mouse tooth development. Orphan GPCRs have been successfully used to identify potential new drug targets via reverse pharmacological screening approaches (Meder et al., 2003; Gruber et al., 2010). ChemR23 exhibits homology to neuropeptide and chemoattractant receptors (Samson et al., 1998), is expressed in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages (Wittamer et al., 2004; Ohira et al., 2010), is a retinoic-acid-responsive receptor (Mårtensson et al., 2005), and interacts with specific ligands, including Chemerin. The ChemR23/Cmklr1 knockout mouse has been reported to have no phenotype (Cash et al., 2008). Our prior report showed that a novel endogenous lipid, Resolvin E1- RvE1, mediates endogenous Chemerin/ChemR23 interactions in vivo, to dampen excessive inflammatory responses and enhance tissue regeneration (Hasturk et al., 2006; Cash et al., 2010). These results suggest that Chemerin/ChemR23-mediated resolution of inflammation may facilitate tissue regeneration in inflammatory disease models, including periodontitis and peritonitis.

Epithelial-mesenchymal cell interactions, important for the development of all organs, direct the proper differentiation of dental epithelial (DE)-derived ameloblasts and dental mesenchymal (DM)-derived odontoblasts, and their subsequent elaboration of enamel and dentin, respectively (Thesleff, 2003; Tucker and Sharpe, 2004). Based on reports of Chemerin signaling in intestinal epithelial cell differentiation (Maheshwari et al., 2009), we hypothesized that Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling might also mediate DE-DM signaling in tooth development. The findings presented here lead to the novel hypothesis that Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling may facilitate proper DE-DM cell interactions during tooth development. These results provide new insight into potential roles for Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling in odontoblast and ameloblast differentiation and identify potential new signaling targets for improved dental tissue engineering applications.

Materials & Methods

Animal Husbandry and Histological Analyses

According to Tufts University IACUC-approved protocols, developmental-stage embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5), E14.5, E16.5, and post-natal day 1 (P1) C57BL/6J wild-type mice were generated and harvested for histological analyses as previously described (Zhang et al., 2012).

Isolation and in vitro Culture of Porcine Dental Cells

Dental epithelial (DE) and mesenchymal (DM) cells were harvested from five-month-old porcine maxillary and mandibular third molar teeth and cultured as previously described (Young et al., 2002, 2005). Cell viability was greater than 98%, as evaluated by Trypan blue and propidium iodide exclusion, and the purity of the isolated fraction was greater than 95%, as confirmed by immunofluorescent staining for the DE cell marker CK14, and the DM cell marker Vimentin.

Antibodies and Reagents

Primary antibodies were: goat anti-mouse Chemerin and isotype control IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); rat anti-mouse ChemR23 monoclonal and isotype control IgG2 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA); rabbit anti-phospho-rS6 (Ser235/Ser236) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and isotype control IgG (Santa Cruz); rabbit anti-Runx2 (Santa Cruz); mouse anti-Vimentin and isotype control IgG1 (Santa Cruz); rabbit anti-human cytokeratin-14 (CK14) and isotype control IgG2a (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); and rabbit anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling Technology). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor® 488 or Alexa-Fluor® 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Recombinant human Chemerin and anti-human ChemR23 monoclonal Ab were purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Rapamycin, an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Immunofluorescent (IF) and Immunohistochemical (IHC) Analysis

Frozen sectioned specimens were prepared as follows. Developmental-stage mouse embryos were collected, fixed with Neutral Buffered Formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Middletown, VA, USA) overnight at 4oC, and washed with PBS. Specimens were cryoprotected by incubation in 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C, and embedded in OCT compound (Andwin Scientific, Schaumburg, IL, USA). Embryos were sectioned at 10-μm intervals and stained with the following primary antibodies: anti-Chemerin goat (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-ChemR23 rat (1:100, eBioscience). Secondary antibodies used were 1:100 anti-rat donkey conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, and 1:100 anti-goat donkey conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 (Life Technologies). Sections were mounted in VECTASHIELD Mounting Media with DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA). Sectioned specimens were incubated with primary antibody in 2% FBS/DPBS overnight at 4°C, washed, with secondary Alexa Fluor® 488 or Alexa-Fluor® 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:250, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 hr at RT in the dark. Specimens were imaged with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope and Axiocam camera (Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany), and manipulated in Adobe Photoshop. Cultured dental cells were plated in 4-well chamber slides (0.5 x 106 cells/well) (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), grown to confluence, and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies as described above. Cultured cells were pre-treated with the monoclonal anti-human ChemR23 antibody (1:100 dilution), rapamycin (10 nM), or isotype-matched IgG control (1:100) for 15 min prior to Chemerin treatment.

Western Blot Analysis

Sub-confluent cultured DM cells were serum-depleted for 24 hrs prior to treatment with Chemerin (0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 nM) for 2 and 24 hrs. Western blotting was used to evaluate the Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling-induced phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 (prS6), as previously described (Ohira et al., 2010). Membranes were incubated with primary antibody (1:1,000) overnight at 4°C, and with secondary antibody [goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate, 1:3,000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology] for 1 hr at room temperature. HRP activity was visualized with a luminol-ECL detection system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) followed by autoradiography. Membranes were stripped and re-blotted with anti-actin antibody (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as an internal control. Band densities were measured with Quantity One® (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and normalized to actin controls.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out by Student’s t test, with p < 0.05 taken as significant.

Results

Chemerin and ChemR23 Expression in Mouse Tooth Development

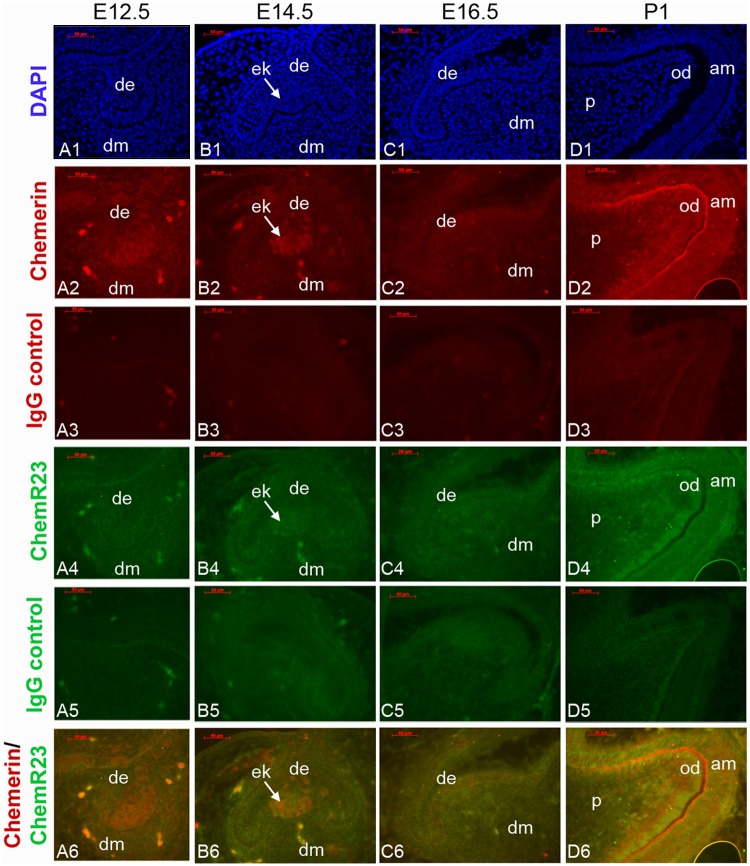

We evaluated Chemerin and ChemR23 expression in mouse molar tooth development using IF analysis of frozen sectioned developmental-stage specimens (Fig. 1). We found that Chemerin (red) was detected in E12.5 DE- and E14.5 DE-derived enamel knot (EK) (Fig. 1, Panels A2, B2, white arrow), and later in P1-stage DE- and DM-derived ameloblasts and odontoblasts (Fig. 1, Panel D2). In contrast, ChemR23 (green) was detected in E16.5 differentiation stages DE and DM (Fig. 1, Panel C4), and P1 odontoblasts and ameloblasts (Fig. 1, Panel D4).

Figure 1.

Chemerin and ChemR23 expression in mouse molar tooth development. DAPI-stained nuclei of developmental-stage mouse tooth frozen sections (Panels A1, B1, C1, D1). IF analysis detected Chemerin (red) in E12.5 DE (Panel A2), E14.5 DE-derived enamel knot (ek, Panel B2), and in ameloblasts and odontoblasts in P1 molar teeth (Panel D2). In contrast, ChemR23 (green) was faintly detected in E16.5 DE and DM (Panels B4, C4), and P1 odontoblasts and ameloblasts (Panels D4). Isotype IgG negative controls (Panels A3-D3, and A5-D5). Overlaid Chemerin/ChemR23 expression patterns are shown in panels A6-D6. Scale bar = 0.05 mm. Abbreviations: am, ameloblast; de, dental epithelium; dm, dental mesenchyme; ob, osteoblast; od, odontoblast; p, pulp.

prS6, pAkt, and Runx2 Expression in Mouse Tooth Development

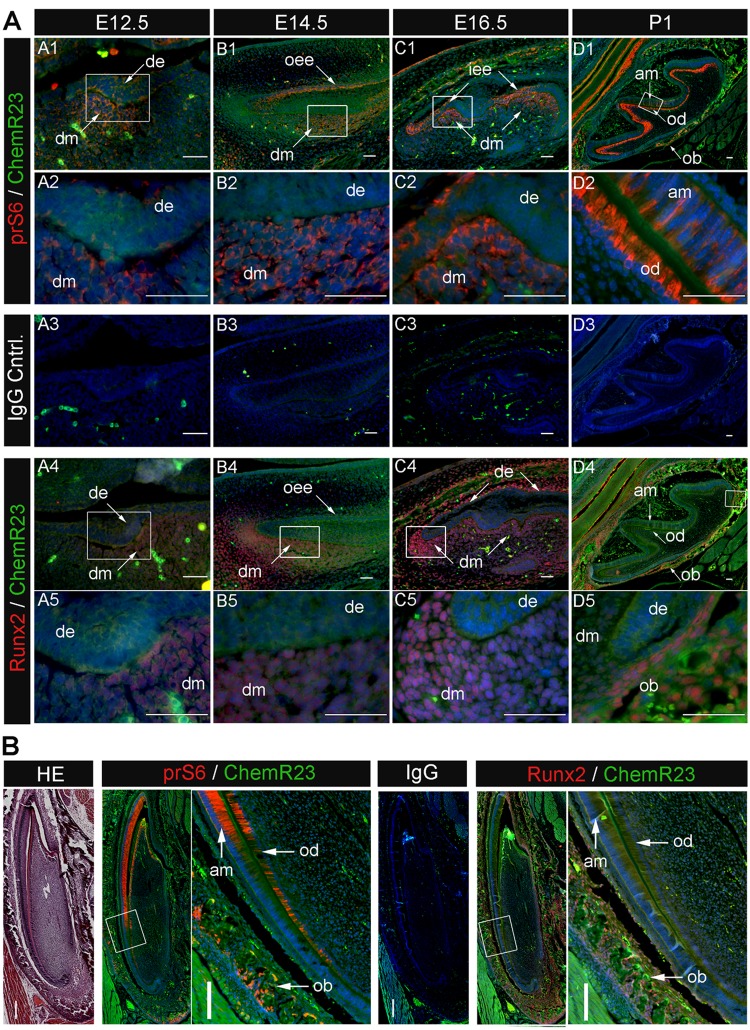

Our previously published report showed that Chemerin treatment induced rS6 and Akt phosphorylation in recombinant human ChemR23 transfected Chinese Hamster Ovary cells (Ohira et al., 2010). Based on these results, here we examined the co- expression of prS6, pAkt, and the Chemerin receptor ChemR23 in developmental-stage mouse molar teeth (Fig. 2). prS6 (red) was detected in E12.5 dental mesenchyme (Fig. 2A, Panels A1, A2, arrows), prior to detectable ChemR23 expression. prS6 was detected in both DM and DE tissues in E14.5 (Fig. 2A, Panels B1, B2, arrows), and in DM E16.5 stage teeth, particularly at tooth cusps (Fig. 2A, Panels C1, C2, arrows). In P1 stage mouse molar teeth, prS6 and ChemR23 expression was detected in differentiated ameloblasts and odontoblasts (Fig. 2A, Panels D1, D2, arrows). pAkt was more broadly expressed in both DE and DM at E16.5, and in DE and DM of P1 stage teeth (Appendix Fig.). We also investigated the co-expression of prS6 and ChemR23 with Runx2, a master osteoblast and odontoblast transcription factor (D’Souza et al., 1999; Komori, 2010) (Fig. 2B). Runx2 was detected in DM of E12.5, E14.5, and E16.5 stage mouse teeth (Fig. 2A, Panels A4, A5, B4, B5, C4, C5), partially overlapping ChemR23 expression in DM. In P1 molar teeth, Runx2 was detected in alveolar bone osteoblasts, while ChemR23 was detected in differentiated DE- and DM-derived ameloblasts and odontoblasts, respectively, and in alveolar osteoblasts (Fig. 2A, Panels D4, D5, arrows).

Figure 2.

Phosphorylated rS6 and Runx2 expression in mouse tooth development. (A) Molar tooth expression patterns. Analyses of developmental-stage mouse tooth sections revealed prS6 and Runx2 expression in the DN of E12.5, E14.5, and E16.5 molar teeth. prS6 was also strongly expressed in differentiated odontoblasts and ameloblasts in PI stage molar teeth, while Runx2 was detected in alveolar bone osteoblasts. Sections were double-labeled with anti-prS6 (red; Panels A1-D1, and enlarged in Panels A2-D2) or anti-Runx2 antibodies (red; Panels A4-D4, and enlarged in Panels A5-D5 ) combined with anti-ChemR23 antibody (green), followed by secondary Alexa Fluor® 568 or Alexa Fluor® 488 antibody. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Isotype control IgG (Panels A3-D3). Scale bar = 0.05 mm. (B) Incisor tooth expression patterns. Similar to molar teeth, mouse P1 incisor teeth exhibited strong prS6 expression in differentiated odontoblasts and ameloblasts, and Runx2 expression in odontoblasts and alveolar-bone-derived osteoblasts. H&E-stained paraffin-sectioned mouse P1 incisor (Panel 1). Merged expression patterns of prS6 (red) and ChemR23 (green) (Panels 2, 3), and Runx2 (red) and ChemR23 (green) (Panels 5, 6). IgG negative control (Panel 4). prS6 and chemR23 are co-expressed in P1 incisor odontoblasts and ameloblasts (Panels 3, 5), while Runx2 and ChemR23 are co-expressed in P1 incisor alveolar bone osteoblasts (Panels 5,6). Scale bar = 0.1 mm. Abbreviations: am, ameloblast; de, dental epithelium; dm, dental mesenchyme; od, odontoblast; ob, osteoblast; oee, outer enamel epithelium; iee, inner enamel epithelium.

We confirmed these results using the continuously erupting incisor mouse model, where P1 mouse incisors revealed similar expression patterns of prS6, Runx2, and ChemR23, as observed in mouse molar teeth (Fig. 2B). prS6 and ChemR23 exhibited overlapping expression in P1 stage odontoblasts and ameloblasts, while again, Runx2 and ChemR23 were co-expressed in alveolar bone osteoblasts (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical analyses of paraffin-sectioned specimens showed similar results, with most distinct expression in differentiated DE and DM cells. Together, these results are consistent with potential roles for Chemerin/ChemR23-mediated prS6 and Runx2 expression in DE and DM cell differentiation.

Chemerin/ChemR23 Signaling in Cultured Dental Epithelial and Dental Mesenchymal Cells

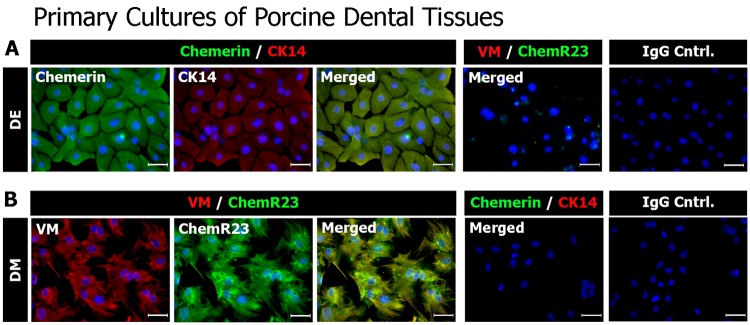

Chemerin, ChemR23, CK14, and Vimentin expression in cultured porcine DE and DM cells was evaluated by immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy. Porcine DE and DM cell cultures were selected for these experiments based on our extensive prior characterizations of these cells for odontoblast and ameloblast differentiation and mineralized dentin and enamel formation (Young et al., 2002, 2005; Abukawa et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). Cultured porcine DE cells obtained from five-month-old pigs, similar in development to mouse P1 teeth, expressed Chemerin and CK14, and did not express ChemR23 or Vimentin, while, in contrast, cultured porcine DM cells expressed Vimentin and ChemR23, and not Chemerin or Ck14 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescent histochemical analyses of cultured porcine DE and DM cells. Cultured porcine DE (top panels) and DM (bottom panels) cells were double-labeled with anti-CK14 and anti-Chemerin, anti-Vimentin, and anti-ChemR23 antibodies, or isotype control IgG, followed by Alexa Fluor® 488 (green) and Alexa Fluor® 568 (red) tagged secondary antibodies. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Chemerin, and not ChemR23, was detected in cultured DE cells. In contrast, ChemR23, and not Chemerin, was detected in cultured DM cells. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Based on these findings, we used Western blot and IF histochemical analyses to evaluate Chemerin signaling in cultured porcine DE and DM cells (Fig. 4). DM cells treated with Chemerin for 2 hrs expressed the downstream Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling molecule, phosphorylated ribosomal S6 (prS6) (Fig. 4A). The specificity of Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling in rS6 phosphorylation was confirmed by pre-treatment of cultured DM cells with ChemR23 antibody or rapamycin, both of which blocked rS6 phosphorylation (Figs. 4B, 4C). Consistent with these results, we next demonstrated that pAkt, an upstream mediator of rS6 phosphorylation via Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling, was phosphorylated within 1 to 5 min after Chemerin treatment, and was dephosphorylated 15 min after Chemerin stimulation (Appendix Fig.).

Figure 4.

Chemerin/ChemR23-mediated ribosomal protein S6 (rS6) phosphorylation and Runx2 expression in cultured porcine DM cells. (A) Chemerin-induced rS6 phosphorylation in DM cells. Serum-depleted cultured DM cells were treated with recombinant Chemerin, followed by Western blot analysis for the detection of prS6 expression. Bar graph presents relative rS6 phosphorylation. Results represent the mean ± SE for 3 separate experiments (*p < 0.05 when compared with unstimulated control). (B) Inhibition of Chemerin-induced rS6 phosphorylation. Cultured DM cells were treated with rapamycin, anti-ChemR23 antibody, or isotype control IgG3, followed by Chemerin stimulation. DE cells were cultured with or without Chemerin, as indicated. Western blot analyses were used to detect prS6 expression. Bar graph presents relative rS6 phosphorylation. Results represent the mean ± SE for 3 separate experiments (*p < 0.05 when compared with unstimulated control). (C) Immunofluorescent (IF) histochemical analysis of rS6 phosphorylation. Cultured DM cells were treated with rapamycin, anti-human ChemR23 antibody, or isotype control IgG3, followed by co-incubation with Chemerin. rS6 phosphorylation was analyzed with anti-prS6 (Ser235/Ser236) primary and Alexa Fluor® 568 secondary (red) antibodies. Actin filaments were labeled with Alexa Fluor® 488-phalloidin (green), and nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Note the strong cytoplasmic expression of prS6 in Chemerin-treated cells. Results represent at least 3 separate experiments. Rapamycin and anti-ChemR23 pre-treatments blocked rS6 phosphorylation in Chemerin-treated cells. Scale bar = 0.05 mm. (D) Chemerin-induced Runx2 expression in DM cells, and not DE cells. Serum-depleted cultured cells were treated with recombinant Chemerin for 24 hrs and used for the detection of Runx2 expression by Western blot analysis. The bar graph presents relative Runx2 expression. Results represent the mean ± SE for 3 separate experiments (*p < 0.05 when compared with unstimulated control). (E) Inhibition of Chemerin-induced Runx2 expression by pharmacological inhibitors. Cultured DM cells were incubated with rapamycin, anti-ChemR23 antibody, or isotype control IgG, followed by 24-hour co-incubation with Chemerin. DE cells were incubated for 24 hrs with or without Chemerin. Runx2 expression was detected by Western blot analysis. The bar graph presents relative Runx2 expression. Results represent the mean ± SE for 3 separate experiments (*p < 0.05 when compared with unstimulated control). (F) Immunofluorescent (IF) histochemical analysis of Runx2 expression. Cultured porcine DM cells were treated with rapamycin, anti-human ChemR23 antibody, or isotype control IgG, followed by 24-hour co-incubation with Chemerin. Cells were analyzed with anti-Runx2 primary and Alexa Fluor® 568 secondary (red) antibodies. Actin filaments were labeled with Alexa Fluor® 488-phalloidin (green), and nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Note the strong nuclear expression of Runx2 in Chemerin-treated cells. Results represent at least 3 separate experiments. Rapamycin and anti-ChemR23 antibody pre-treatments blocked Chemerin-induced Runx2 expression. Scale bar = 0.05 mm.

We also found that cultured DM cells treated with Chemerin for 24 hrs expressed Runx2 (Fig. 4D) and that Chemerin-induced Runx2 expression was blocked by pre-treatment with an anti-ChemR23 antibody or rapamycin (Figs. 4E, 4F). Cultured DE cells did not express Runx2 in response to Chemerin treatment (Fig. 4E). Together, these results are consistent with a model where DE-cell-secreted Chemerin signals through DM-cell-expressed ChemR23, to induce Akt and rS6 phosphorylation and Runx2 expression in DM cells, leading to odontoblast differentiation.

We also examined the co-localization of pAkt and prS6 in E16.5 and P1 mouse molar teeth. pAkt and prS6 exhibited overlapping expression in the dental mesenchyme and dental epithelium at E16.5 stage molar teeth (Appendix Fig., A). Interestingly, in P1 stage molar teeth, prS6 was evenly expressed in both differentiated and undifferentiated odontoblasts, while pAkt expression appeared slightly reduced in undifferentiated odontoblasts (arrow) (Appendix Fig., B). We also found that Chemerin induced pAkt expression in cultured dental mesenchyme, but not in cultured dental epithelial cells (Appendix Fig., C).

Discussion

ChemR23 is a chemotactic receptor previously shown to be expressed in monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells (Arita et al., 2005; Parolini et al., 2007; Serhan et al., 2008; Shimizu, 2009) and also functions in both adaptive and innate immunity (Zabel et al., 2005; Parolini et al., 2007; Yoshimura and Oppenheim, 2008). Our previously published report showed that Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling regulated Akt phosphorylation in human CHO cells and induced rS6 phosphorylation via PI3K-Akt and ERK signaling pathways (Ohira et al., 2010). The interesting finding that Chemerin can induce calcium mobilization in a ChemR23-dependent manner (Wittamer et al., 2003) is consistent with potential roles for Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling in mineralized tissue differentiation, including tooth development. Here we show that Chemerin and ChemR23 are expressed in differentiating dental epithelial and dental mesenchymal cells. It is interesting that while Chemerin is detected in early-stage, undifferentiated dental epithelium, ChemR23 is first detected in differentiation-stage tooth development. It is possible that Chemerin may signal through other receptors in early stages of tooth development, such as GPR1 or CCRL2. The expression patterns of these and other receptors in tooth development remain to be determined. Another interesting finding is that Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling may function in both ameloblast and odontoblast differentiation. Additional analyses of differentiation marker expression in cultured pre-ameloblast and odontoblast differentiation is needed for better definition of these roles.

Ribosomal S6 and Akt phosphorylation is regulated by several diverse signaling pathways. We found that Akt and rS6 are phosphorylated in cultured DM cells stimulated with Chemerin, and not in Chemerin-stimulated cultured DE cells. In addition to these phosphorylation events, we found that Runx2 is induced in Chemerin-stimulated cultured DM cells, and not in cultured DE cells. The specificity of the Chemerin/ChemR23-mediated rS6 and Akt phosphorylation events, and Runx2 expression, was demonstrated with a function blocking antibody to ChemR23, and the chemical inhibitor rapamyacin. Additional studies will determine the mechanism of these interactions.

Runx2 directs dental mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation into pre-odontoblasts and immature odontoblasts (D’Souza et al., 1999; Tucker and Sharpe, 2004), but was found to inhibit late-stage odontoblast differentiation (Komori, 2010). Prior reports showed that Akt1 could enhance Runx2-induced osteoblast differentiation and that Akt1-deficient osteoblasts are susceptible to apoptosis, resulting in decreased bone mass (Kawamura et al., 2007). Consistent with this report, here we demonstrate that Chemerin can induce Runx2 expression, and Akt and rS6 phosphorylation in cultured DM cells, but not in cultured DE cells. It is noteworthy that Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (BMP-2), which functions in both odontoblast and osteoblast differentiation (Iohara et al., 2004; Saito et al., 2004), has also been shown to be regulated by the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway (Langenfeld et al., 2005). Together, these results suggest potential roles for Chemerin/ChemR23-mediated Akt/mTOR signaling in ameloblast, odontoblast, and alveolar-bone-derived osteoblast differentiation.

In summary, here we present evidence for Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling in DE and DM cell differentiation in tooth development. Our results are consistent with a model where Chemerin/ChemR23 signaling may mediate DE and DM cell cross-talk, leading to odontoblast and ameloblast differentiation. Differences were observed in the expression patterns of Chemerin, ChemR23, prS6, and pAkt in the in vitro-cultured vs. developmental-stage mouse tooth tissues. One obvious explanation for this disparity is that cultured dental cells are not regulated by the same signals that guide normal tooth development, where DE and DM cells remain in close physical contact throughout tooth development. Future studies will elucidate the molecular mechanisms regulating Chemerin/ChemR23-mediated DE/DM cell signaling, leading to ameloblast, odontoblast, and alveolar bone osteoblast differentiation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert advice and guidance of all of the members of the Yelick Laboratory, in particular that of Dr. Weibo Zhang and Betsy Vazquez.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the NIH/NIDCR (grant R01DE016132 to PCY).

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Abukawa H, Zhang W, Young CS, Asrican R, Vacanti JP, Kaban LB, et al. (2009). Reconstructing mandibular defects using autologous tissue-engineered tooth and bone constructs. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 67:335–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita M, Bianchini F, Aliberti J, Sher A, Chiang N, Hong S, et al. (2005). Stereochemical assignment, antiinflammatory properties, and receptor for the omega-3 lipid mediator resolvin E1. J Exp Med 201:713–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash JL, Hart R, Russ A, Dixon JP, Colledge WH, Doran J, et al. (2008). Synthetic chemerin-derived peptides suppress inflammation through ChemR23. J Exp Med 205:767–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash JL, Christian AR, Greaves DR. (2010). Chemerin peptides promote phagocytosis in a ChemR23- and Syk-dependent manner. J Immunol 184:5315–5324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza RN, Aberg T, Gaikwad J, Cavender A, Owen M, Karsenty G, et al. (1999). Cbfa1 is required for epithelial-mesenchymal interactions regulating tooth development in mice. Development 126:2911–2920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber CW, Muttenthaler M, Freissmuth M. (2010). Ligand-based peptide design and combinatorial peptide libraries to target G protein-coupled receptors. Curr Pharm Des 16:3071–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasturk H, Kantarci A, Ohira T, Arita M, Ebrahimi N, Chiang N, et al. (2006). RvE1 protects from local inflammation and osteoclast-mediated bone destruction in periodontitis. FASEB J 20:401–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iohara K, Nakashima M, Ito M, Ishikawa M, Nakasima A, Akamine A. (2004). Dentin regeneration by dental pulp stem cell therapy with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2. J Dent Res 83:590–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura N, Kugimiya F, Oshima Y, Ohba S, Ikeda T, Saito T, et al. (2007). Akt1 in osteoblasts and osteoclasts controls bone remodeling. PLoS One 2:e1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T. (2010). Regulation of bone development and extracellular matrix protein genes by RUNX2. Cell Tissue Res 339:189–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenfeld EM, Kong Y, Langenfeld J. (2005). Bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced transformation involves the activation of mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol Cancer Res 3:679–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari A, Kurundkar AR, Shaik SS, Kelly DR, Hartman Y, Zhang W, et al. (2009). Epithelial cells in fetal intestine produce chemerin to recruit macrophages. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297:G1–G10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson UE, Bristulf J, Owman C, Olde B. (2005). The mouse chemerin receptor gene, mcmklr1, utilizes alternative promoters for transcription and is regulated by all-trans retinoic acid. Gene 350:65–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meder W, Wendland M, Busmann A, Kutzleb C, Spodsberg N, John H, et al. (2003). Characterization of human circulating TIG2 as a ligand for the orphan receptor ChemR23. FEBS Lett 555:495–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira T, Arita M, Omori K, Recchiuti A, Van Dyke TE, Serhan CN. (2010). Resolvin E1 receptor activation signals phosphorylation and phagocytosis. J Biol Chem 285:3451–3461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolini S, Santoro A, Marcenaro E, Luini W, Massardi L, Facchetti F, et al. (2007). The role of chemerin in the colocalization of NK and dendritic cell subsets into inflamed tissues. Blood 109:3625–3632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Ogawa M, Hata Y, Bessho K. (2004). Acceleration effect of human recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-2 on differentiation of human pulp cells into odontoblasts. J Endod 30:205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson M, Edinger AL, Stordeur P, Rucker J, Verhasselt V, Sharron M, et al. (1998). ChemR23, a putative chemoattractant receptor, is expressed in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages and is a coreceptor for SIV and some primary HIV-1 strains. Eur J Immunol 28:1689–1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. (2008). Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol 8:349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T. (2009). Lipid mediators in health and disease: enzymes and receptors as therapeutic targets for the regulation of immunity and inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 49:123–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thesleff I. (2003). Epithelial-mesenchymal signalling regulating tooth morphogenesis. J Cell Sci 116:1647–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker A, Sharpe P. (2004). The cutting-edge of mammalian development; how the embryo makes teeth. Nat Rev Genet 5:499–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittamer V, Franssen JD, Vulcano M, Mirjolet JF, Le Poul E, Migeotte I, et al. (2003). Specific recruitment of antigen-presenting cells by chemerin, a novel processed ligand from human inflammatory fluids. J Exp Med 198:977–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittamer V, Grégoire F, Robberecht P, Vassart G, Communi D, Parmentier M. (2004). The C-terminal nonapeptide of mature chemerin activates the chemerin receptor with low nanomolar potency. J Biol Chem 279:9956–9962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura T, Oppenheim JJ. (2008). Chemerin reveals its chimeric nature. J Exp Med 205:2187–2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CS, Terada S, Vacanti JP, Honda M, Bartlett JD, Yelick PC. (2002). Tissue engineering of complex tooth structures on biodegradable polymer scaffolds. J Dent Res 81:695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CS, Abukawa H, Asrican R, Ravens M, Troulis MJ, Kaban LB, et al. (2005). Tissue-engineered hybrid tooth and bone. Tissue Eng 11:1599–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel BA, Allen SJ, Kulig P, Allen JA, Cichy J, Handel TM, et al. (2005). Chemerin activation by serine proteases of the coagulation, fibrinolytic, and inflammatory cascades. J Biol Chem 280:34661–34666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Abukawa H, Troulis MJ, Kaban LB, Vacanti JP, Yelick PC. (2009). Tissue engineered hybrid tooth-bone constructs. Methods 47:122–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Vazquez B, Andreeva V, Spear D, Kong E, Hinds PW, et al. (2012). Discrete phosphorylated retinoblastoma protein isoform expression in mouse tooth development. J Mol Histol 43:281–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]