Abstract

This study was conducted to assess caries treatment thresholds among Japanese dentists and to identify characteristics associated with their decision to intervene surgically in proximal caries lesions within the enamel. Participants (n = 189) were shown radiographic images depicting interproximal caries and asked to indicate the lesion depth at which they would surgically intervene in both high- and low-caries-risk scenarios. Differences in treatment thresholds were then assessed via chi-square tests, and associations between the decision to intervene and dentist, practice, and patient characteristics were analyzed via logistic regression. The proportion of dentists who indicated surgical intervention into enamel was significantly higher in the high-caries-risk scenario (73.8%, N = 138) than in the low-caries-risk scenario (46.5%, N = 87) (p < 0.001). In multivariate analyses for a high-caries-risk scenario, gender of dentist, city population, type of practice, conducting caries-risk assessment, and administering diet counseling were significant factors associated with surgical enamel intervention. However, for a low-caries-risk scenario, city population, type of practice, and use of a dental explorer were the factors significantly associated with surgical enamel intervention. These findings demonstrate that restorative treatment thresholds for interproximal primary caries differ by caries risk. Most participants would restore lesions within the enamel for high-caries-risk individuals (Clinicaltrials.gov registration number NCT01680848).

Keywords: dental caries, dentist’s practice pattern, diagnosis, evidence-based dentistry, clinical research, epidemiology

Introduction

The interproximal tooth surface is an important site for the diagnosis and treatment of dental caries (Mejàre et al., 2004; Anderson et al., 2005). In the presence of enamel surface integrity, caries lesions present in the enamel and/or dentin can be managed via remineralization therapies (Sawyer and Donly, 2004; Donly and Brown, 2005), although the extent of remineralization is limited by the caries risk of the individual environment, as explained in the concept of caries balance (Featherstone, 2006; Featherstone et al., 2012). Elderton’s empirical work about the restorative cycle is at the heart of why the profession is concerned about the adverse effects of intervening surgically before it becomes necessary (Elderton, 1993). Consensus has been reached regarding the potential for non-cavitated enamel lesions to reverse, and the restorative intervention of non-cavitated caries confined to enamel is inappropriate (Tyas et al., 2000).

However, several studies have documented that the proportion of dentists who would intervene surgically into enamel for treatment of proximal caries varies widely—in Sweden, 1% (Mejàre et al., 1999); in Norway, 3.6% (Tveit et al., 1999); and in Brazil, 54.5% (Traebert et al., 2005)—when the cavity is located in the inner half of the enamel only. When the cavity is located in the inner or outer half of the enamel up to the EDJ, the following results have been reported: Scandinavia, 0 to 21% (Gordan et al., 2009); and the United States, 8 to 86% (Gordan et al., 2009). The abovementioned results show that the treatment thresholds of interproximal primary caries differ among populations.

A previous study by the Dental Practice-based Research Network (DPBRN), which includes practitioners from both the United States and Scandinavia, noted substantial variation among dentists in restorative treatment thresholds based on radiographic lesion depth (Gordan et al., 2009), with most opting for surgical restoration of lesions that were still within the enamel surface for high-caries-risk individuals. Dentists’ decisions to intervene surgically in the caries process differed based on patient caries risk, although most dentists in Scandinavia chose not to restore lesions that were limited to enamel (Gordan et al., 2009). However, no previous studies conducted in Japan have examined differences in treatment threshold at which practitioners would decide to intervene surgically for interproximal caries. The recent establishment of the Dental Practice-based Research Network Japan (JDPBRN) created an opportunity for international comparisons to be made. JDPBRN is a consortium of dental practices with a broad representation of practice types, treatment philosophies, and patient populations, having a shared mission with DPBRN (Gilbert et al., 2008).

The purposes of this study were to: (1) examine differences in treatment thresholds for interproximal primary caries in Japanese dentists, and (2) identify characteristics among Japanese dentists associated with the decision to intervene surgically in proximal lesions that were still within the enamel.

Materials & Methods

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study consisting of a questionnaire survey in Japan between May 2011 and February 2012. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine (No. E1157). We used the same questionnaire as used in the DPBRN Study, “Assessment of Caries Diagnosis and Caries Treatment” (Gordan et al. 2009), and the DPBRN Enrollment Questionnaire (Makhija et al., 2009). Four dentists and clinical epidemiologists translated these questionnaires into Japanese. The translated version of this questionnaire is available at http://www.dentalpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/Study%201(Japanese%20Version).pdf. Dentists were asked about assessment of caries diagnosis and treatment, treatment thresholds by hypothetical scenarios with radiographic images, and patient and dentist background data.

The network regions of the JDPBRN represent all 7 districts in Japan (Hokkaido, Tohoku, Kanto, Chubu, Kansai, Chugoku-Shikoku, and Kyushu). Every region has a Regional Coordinator who distributed and gathered the questionnaires (Gilbert et al., 2008). Dentists were asked to complete the questionnaire by hand and return it to the assigned Regional Coordinator in a pre-addressed envelope. The Regional Coordinator then reviewed the questionnaire for completeness (Gordan et al. 2009, 2010).

Participants

This study queried dentists working in outpatient dental practices who have affiliated with JDPBRN to investigate research questions and to share experiences and expertise (n = 282). Participants were recruited from the JDPBRN Web site and mailings if they indicated that they perform some measure of restorative dentistry at their practice. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation in this study.

Hypothetical Scenarios with Radiographic Images and Patient Background Data

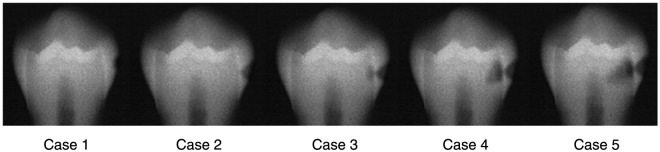

Participants indicated their treatment decision from options presented for cases described in the questionnaire. A series of 5 radiographic images of caries located on the interproximal surface of a mandibular premolar, together with a description of the patient, was presented, portraying increasingly deep caries lesions (Fig.). We inquired about the treatment decision point (shallowest depth at which the dentist would surgically restore the tooth) for each case under 2 different caries-risk conditions (low and high risk of developing caries). The exact wording of each case scenario is provided in the Fig. Case 1 showed radiolucency in the outer half of the enamel, while Case 2 showed radiolucency reaching the inner half of the enamel. Cases 3, 4, and 5 showed radiolucency in the outer, middle, and inner thirds of the dentin, respectively (Espelid et al., 1997).

Figure.

Scenarios presented to participating dentists. Case scenario: Patient is a 30-year-old woman with no relevant medical history. She has no complaints and is in your office today for a routine visit. She has been attending your practice on a regular basis for the past 6 years. Questions 1 and 2: Please indicate the one number that corresponds to the lesion depth at which you would do a permanent restoration (composite, amalgam, etc.) instead of doing only preventive therapy…1.…if the patient has no dental restorations, no dental caries, and is not missing any teeth…2.…if the patient has 12 teeth with existing dental restorations, heavy plaque and calculus, multiple Class V white-spot lesions, and is not missing any teeth. (Reprinted from Espelid et al., 1997, with permission.)

Variable Selection

To identify dentist, practice, and patient characteristics associated with adoption of an enamel-based interproximal restorative treatment threshold, we discussed theoretical models identified in accordance with previous studies (Bader and Shugars, 1997; Gilbert et al., 2006; Gordan et al., 2009). In addition, explanatory variables were extracted, consisting of 4 categories: (1) dentists’ individual characteristics (years since graduation from dental school, race/ethnicity, gender), (2) practice setting (type of practice and busyness, patient waiting time for restorative dentistry, city population [government-ordinance-designated city with population over 700,000 or not]), (3) patient population characteristics (dental insurance coverage, percentage of patients who self-pay, patient age distribution, racial/ethnic distribution), and (4) procedure-related characteristics (percentage of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative procedures, aesthetic procedures, and extractions; whether or not caries risk is assessed as a routine part of treatment planning; percentage of patients examined by means of a dental explorer for primary occlusal caries diagnosis, and receiving diet counseling).

Statistical Analysis

Description of Treatment Thresholds

We determined the numbers (percentage) of dentists who would indicate surgical restorative intervention for each case, 1 through 5. We performed chi-square tests to assess the association between treatment thresholds and participants. We examined differences between the numbers of dentists who would indicate surgical restorative intervention into enamel (combining Cases 1 and 2) or dentin (combining Cases 3, 4, and 5).

Factors Affecting Decision to Intervene into Enamel or Dentin Lesions

Descriptive analysis was conducted via univariate regression analysis for explanatory variables associated with dentists’ use of an enamel-based interproximal restorative treatment threshold. Subsequently, we conducted multiple logistic regression analysis to examine the relationship between explanatory variables and intervention into enamel or dentin. The odds ratios were calculated together with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics (version 19.0, IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Participants’ Demographic Information

Questionnaires were distributed to 282 dentists, and 189 (67%) were ultimately collected. Demographic characteristics of study participants from Japan are shown in Table 1. The mean number of years elapsed since graduation from dental school was 18.5 ± 9.9, and participants were predominantly male (N = 154, 82.4%). Race/ethnicity was almost entirely Asian (N = 186, 98.9%). With regard to practice setting, 40.4% (N = 76) of practices were established in government-ordinance-designated cities of over 700,000. The percentage of dentists who perform caries-risk assessment as a routine part of treatment planning was 25.9% (N = 49). Most dentists surveyed (N = 159, 84.1%) used a dental explorer for the diagnosis of primary occlusal caries. Approximately 21% of all patients received diet counseling.

Table 1.

Distribution of Dentists’, Practices’, Patients’, and Dental Procedures’ Characteristics of Participants

| Number (%) or Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Dentists’ Individual Characteristics | |

| Years since graduation from dental school (year)* (N = 185) | 18.5 ± 9.9 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) (N = 188) | |

| Asian | 186 (98.9) |

| White | 1 (0.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.5) |

| Gender (male) (N = 187) | 154 (82.4) |

| Practice Setting | |

| Practice busyness, n (%) (N = 181) | |

| Too busy to treat all people requesting appointments | 19 (10.5) |

| Provided care to all, but the practice was overburdened | 72 (39.8) |

| Provided care to all, but the practice was not overburdened | 59 (32.6) |

| Not busy enough | 31 (17.1) |

| Patient waiting time for restorative dentistry (min)* (N = 182) | 12.7 (10.3) |

| City population (government-ordinance-designated city), n (%) (N = 189) | 76 (40.4) |

| Type of practice, n (%) (N = 188) | |

| Employed by another dentist | 77 (41.0) |

| Self-employed without partners and without sharing of income, costs, or office space | 105 (55.9) |

| Self-employed without partners but share costs of office and/or assistants, etc. | 3 (1.6) |

| Self-employed as a partner in a complete partnership | 3 (1.6) |

| Patient Population | |

| Dental insurance coverage (%)* (N = 183) | 88.5 ± 20.3 |

| Percentage of patients who self-pay (%)* (N = 183) | 8.6 ± 16.6 |

| Patient age distribution* | |

| 1-18 yrs old (%) (N = 183) | 16.1 ± 13.2 |

| 19-44 yrs old (%) (N = 188) | 24.8 ± 11.0 |

| 45-64 yrs old (%) (N = 183) | 30.4 ± 11.2 |

| 65+ yrs (%) (N = 183) | 28.5 ± 17.4 |

| Racial/ethnic distribution* | |

| White (%)(N = 184) | 0.3 ± 1.2 |

| Black or African-American (%) (N = 184) | 0.04 ± 0.2 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native (%) (N = 184) | 0.01 ± 0.07 |

| Asian (%) N = 185) | 98.9 ± 7.4 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (%) (N = 184) | 0.02 ± 0.2 |

| Others (%) (N = 184) | 0.7 ± 7.4 |

| Dental Procedure Characteristics | |

| Percentage of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative procedures (%)* (N = 183) | 28.7 ± 14.2 |

| Percentage of patient contact time spent each day doing aesthetic procedures (%)* (N = 185) | 4.5 ± 7.2 |

| Percentage of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions (%)* (N = 183) | 8.8 ± 6.2 |

| Caries risk is assessed as a routine part of treatment planning, n (%) (N = 189) | 49 (25.9) |

| Percentage of patients in whom a dental explorer is to be used for a primary occlusal caries diagnosis, n (%) (N = 189) | |

| 0% (never) | 30 (15.9) |

| 1%-24% | 51 (27.0) |

| 25%-49% | 12 (6.3) |

| 50%-74% | 20 (10.6) |

| 75%-99% | 29 (15.3) |

| 100% (every time) | 47 (24.9) |

| Percentage of patients who receive diet counseling (%)* (N = 183) | 21.4 ± 27.2 |

Mean ± SD.

Treatment Thresholds

Rates of indication for restorative intervention for Cases 1 through 5 are shown in Table 2. In the high-caries-risk scenario, the percentage of participants who would indicate surgical intervention increased in the following order: Case 2 > 3 > 1 > 4 > 5. Conversely, in the low-caries-risk scenario, it increased in the following order: Case 2 = 3 > 4 > 1 > 5. In the high-caries-risk scenario, the percentage of participants who would indicate surgical intervention into enamel (combining Cases 1 and 2) and dentin (combining Cases 3, 4, and 5) were 73.8% (N = 138) and 26.2% (N = 49), respectively. Conversely, in the low-caries-risk scenario, the percentage for enamel was 46.5% (N = 87) and that for dentin was 53.5% (N = 100). In the high-caries-risk scenario, the proportion of dentists who would intervene surgically into enamel was found to be significantly higher than that among dentists in the low-caries-risk scenario (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Dentists’ Decision to Intervene Surgically in Enamel and Dentin According to Patient’s Caries Risk

| High-caries-risk Scenario Frequency (%) (n =187) | Low-caries-risk Scenario Frequency (%) (n =187) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case | |||

| Case 1 | 35 (18.7%) | 7 (3.7%) | |

| Case 2 | 103 (55.1%) | 80 (42.8%) | |

| Case 3 | 43 (23.0%) | 80 (42.8%) | |

| Case 4 | 5 (2.7%) | 17 (9.1%) | |

| Case 5 | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.6%) | |

| Enamel or Dentin† | |||

| Enamel | 138 (73.8%) | 87 (46.5%) | |

| Dentin | 49 (26.2%) | 100 (53.5%) | p< 0.001 |

Chi-square test.

Enamel: combining Cases 1 and 2. Dentin: combining Cases 3, 4, and 5.

Factors Affecting Decision to Intervene Surgically in Enamel and Dentin Lesions

The results of multiple logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 3. In the high-caries-risk model, 5 factors were significantly associated with the decision to intervene surgically in interproximal enamel. Odds ratios (CI) were: gender, 3.58 (1.10-11.70); city population, 3.69 (1.28-10.61); type of practice, 0.32 (0.11-0.98); caries-risk assessment, 2.85 (1.00-8.10); and option of diet counseling, 0.98 (0.97-1.00). In the low-caries-risk model, 3 factors were significantly associated with dentists’ decision to intervene surgically in interproximal enamel. Odds ratios (CI) were: city population, 2.78 (1.14-6.75); type of practice, 0.37 (0.14-0.95); and use of a dental explorer, 12.67 (2.82-56.86).

Table 3.

Factors Affecting Dentists’ Decision to Intervene Surgically in Enamel and Dentin Lesions According to Patient’s Caries Risk

| High-caries-risk Scenario |

Low-caries-risk Scenario |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI |

95% CI |

|||||||

| Variable | OR* | Lower | Upper | p Value | OR* | Lower | Upper | p Value |

| Gender (reference female) | 3.58 | 1.10 | 11.70 | 0.035 | 3.38 | 1.00 | 11.49 | 0.051 |

| City population (reference non-government-ordinance-designated city) | 3.69 | 1.28 | 10.61 | 0.016 | 2.78 | 1.14 | 6.75 | 0.024 |

| Type of practice | ||||||||

| Employed by another dentist | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Self-employed without partners and without sharing of income, costs, or office space | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.98 | 0.046 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.040 |

| Self-employed without partners but share costs of office space, assistants, etc. | 0.23 | 0.01 | 7.56 | 0.409 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 12.04 | 0.548 |

| Whether or not caries-risk assessment is done as a routine part of treatment planning (reference: yes) | 2.85 | 1.00 | 8.10 | 0.049 | 1.15 | 0.41 | 3.28 | 0.788 |

| Percentage of patients examined by means of a dental explorer for a primary occlusal caries diagnosis | ||||||||

| 0% (never) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1%-24% | 1.77 | 0.44 | 7.19 | 0.424 | 2.32 | 0.60 | 9.07 | 0.225 |

| 25%-49% | 1.79 | 0.26 | 12.15 | 0.550 | 4.48 | 0.64 | 31.26 | 0.131 |

| 50%-74% | 2.94 | 0.39 | 22.45 | 0.298 | 7.47 | 1.42 | 39.31 | 0.018 |

| 75%-99% | 1.98 | 0.38 | 10.27 | 0.415 | 4.13 | 0.79 | 21.65 | 0.094 |

| >100% (every time) | 2.76 | 0.60 | 12.66 | 0.191 | 12.67 | 2.82 | 56.86 | 0.001 |

| Percentage of patients who receive diet counseling (%)** | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.039 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.052 |

CI, confidence interval.

Overall predictive accuracy is 82.2% for high-caries-risk and 74.2% for low-caries-risk scenario models.

No significant differences were found for the following variables: years since graduation from dental school; practice busyness; patient waiting time for restorative dentistry; percentage of patients who self-pay; patient age distribution; percentage of patient contact time spent each day doing either restorative, aesthetic, or extraction procedures.

Correlation coefficient between “dental insurance coverage” and “percentage of patients who self-pay” was 0.80, and the latter was included in the model. Dentists’ and patients’ ”Race/ethnicity“ were excluded because over 99% of dentists and patients were Japanese.

Adjusted for years since graduation from dental school, practice busyness, patient waiting time for restorative dentistry, percentage of patients who self-pay, patient age distribution, and percentage of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative procedures, aesthetic procedures, and extraction procedures in both high- and low-caries-risk models.

Continuous variable.

Discussion

The participants would intervene surgically into interproximal enamel earlier for high-caries-risk patients than they would in low-risk ones. Results of multiple logistic regression analysis suggested that several variables were associated with dentists’ decision to intervene surgically in interproximal enamel. Specifically, gender, city population, type of practice, caries-risk assessment, percentage of patients examined by means of a dental explorer for primary occlusal caries diagnosis, and diet therapy were significantly associated with the decision to intervene surgically in interproximal enamel.

According to the result of the same scenario survey, conducted by Gordan et al. (2009) (N = 500), in the high- and low-caries-risk scenario, the percentages of overall DPBRN dentists who would indicate surgical intervention into enamel are 75.4% and 40.4%, respectively. Subgroup analysis revealed that among dentists in Scandinavia (N = 29), in the high- and low-caries-risk scenarios, the percentages of dentists who would indicate surgical intervention into enamel are 21% and 0%, respectively. The results of this study may suggest that, overall, dentists in the DPBRN and JDPBRN have similar tendencies to intervene surgically into enamel, and Scandinavia had the lowest proportion.

Male dentists (N = 154, 82.4%) opted to intervene in enamel surfaces significantly more often than female dentists in the high-caries-risk model. Conversely, self-employed dentists without partners who did not share income, costs, or office space (N = 105, 55.9%) opted to intervene in enamel surfaces significantly less often than those working under another dentist (N = 77, 41.0%). These findings—that gender and type of practice for employment are associated with enamel intervention—are consistent with those of a previous US study (Gordan et al., 2009). The previous study, conducted in Sweden, also identified an association between decision and type of practice (Mejàre et al., 1999).

However, we also detected no significant association between practice busyness and enamel intervention, a finding not consistent with results from the previous US study (Gordan et al., 2009), suggesting that perhaps Japanese dentists do not adopt certain treatment thresholds based on practice busyness. While we were unable to identify the reason for this discrepancy based on findings from the present study, possibly differences in health insurance systems among the countries involved may account for this finding.

Risk assessment is essential in the diagnosis and treatment of dental caries (Kidd, 2005). Here, caries-risk assessment was conducted by only 26% (N = 49) of participants as a routine part of treatment planning, as opposed to approximately 69% (N = 344) of dentists in the DPBRN (Gordan et al., 2009). This finding clearly demonstrates that while caries-risk assessment is common practice among dentists participating in the DPBRN, this is not yet the case for dentists participating in JDPBRN. Furthermore, JDPBRN dentists who did not perform caries-risk assessment tended to perform surgical restorative treatment into the enamel in the high-risk scenario in the present study. This finding suggests that JDPBRN dentists who conduct caries-risk assessment may base their treatment thresholds on a patient’s caries risk.

The use of a sharp dental explorer is no longer internationally accepted for the diagnosis of occlusal caries, given the risk of causing physical damage by inserting a hard metal point into a site already rendered fragile by demineralization (Ekstrand et al., 1987; van Dorp et al., 1988; Dodds, 1996). In addition, the use of sharp explorers in the detection of primary occlusal caries appears to contribute little diagnostic information to other modalities and may in fact be detrimental (NIH, 2001). In the present study, 84% (N = 159) of respondents used a dental explorer for the assessment of primary occlusal caries lesions in some way, a markedly high proportion. Furthermore, those who used dental explorers more often tended to intervene surgically into enamel relatively early for primary interproximal caries lesions in low-risk patients. Taken together, these findings suggest that further dissemination of information on the appropriate use of dental explorers may help reduce the incidence of interproximal enamel surgical intervention thresholds.

A previous study demonstrated that sugar regulation (World Health Organization, 2003) as well as increased vegetable consumption (Yoshihara et al., 2009) are effective means of dental diseases prevention. The mean percentage of patients receiving diet counseling in the present study was 21%, a relatively low proportion. As such, we conclude that dental practices should take greater steps to provide diet counseling and encourage patient participation in this endeavor. Multiple regression analysis also revealed that the administration of diet counseling was significantly associated with interproximal enamel surgical intervention thresholds; dentists focusing on diet counseling tended not to intervene surgically into enamel.

This study featured a relatively wide variety of participants, with respondents from all over Japan. The age and gender distribution of this study sample was similar to the actual distribution in Japan (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2010), thereby enhancing the generalizability of the findings. However, the study results should be approached with caution. First, participants were not selected by random sampling. Second, given the cross-sectional nature of our study, causative relationships between factors and use of an enamel-based interproximal surgical treatment threshold were difficult to assess. Finally, only radiographic data and hypothetical scenarios were available to participants for making their decisions. The treatment thresholds in an actual setting may differ, since actual patients have additional clinical information available at the time of diagnosis.

In conclusion, most dentists would restore lesions within the enamel for high-caries-risk individuals. The translation of research findings to clinical practices is complex (Teachman et al., 2012). As a first step to improving clinical decision-making regarding surgical intervention at early stages of caries lesions, results of this study should be reported to the dentists for the purpose of self-assessing their daily dental practice.

Footnotes

Certain components of this investigation were supported by NIH grants U01-DE-16746, U01-DE-16747, and U19-DE-22516. Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the respective organizations or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anderson M, Stecksen-Blicks C, Stenlund H, Ranggard L, Tsilingaridis G, Mejàre I. (2005). Detection of approximal caries in 5-year old Swedish children. Caries Res 39:92–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader JD, Shugars DA. (1997). What do we know about how dentists make caries-related treatment decisions? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 25:97–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds MW. (1996). Dental caries diagnosis — toward the 21st century. To fill or not to fill? — a new technology may solve the dentist’s dilemma. Nat Med 2:283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donly KJ, Brown DJ. (2005). Indentify, protect, restore: emerging issues in approaching children’s oral health. Gen Dent 53:106–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand K, Qvist V, Thylstrup A. (1987). Light microscope study of the effect of probing in occlusal surfaces. Caries Res 21:368–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elderton RJ. (1993). Overtreatment with restorative dentistry: when to intervene? Int Dent J 43:17–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelid I, Tveit AB, Mejàre I, Nyvad B. (1997). Caries—New knowledge or old truths? Nor Dent J 107:66–74 [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone JD. (2006). Caries prevention and reversal based on the caries balance. Pediatr Dent 28:128–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone JD, White JM, Hoover CI, Rapozo-Hilo M, Weintraub JA, Wilson RS, et al. (2012). A randomized clinical trial of anticaries therapies targeted according to risk assessment (caries management by risk assessment). Caries Res 46:118–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert GH, Shewchuk RM, Litaker MS. (2006). Effect of dental practice characteristics on racial disparities in patient-specific tooth loss. Med Care 44:414–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Rindal DB, Pihlstrom DJ, Benjamin PL, Wallace MC; DPBRN Collaborative Group (2008). The creation and development of the dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc 139:74–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordan VV, Garvan CW, Heft MW, Fellows JL, Qvist V, Rindal DB, et al. (2009). Restorative treatment thresholds for interproximal primary caries based on radiographic images: findings from the Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Gen Dent 57:654–663 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordan VV, Bader JD, Garvan CW, Richman JS, Qvist V, Fellows JL, et al. , Dental Practice-based Research Network Collaborative Group (2010). Restorative treatment thresholds for occlusal primary caries among dentists in the dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc 141:171–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd EAM. (2005). Essentials of dental caries: the disease and its management. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2003). Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 916: i-viii, 1-149, backcover. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ; DPBRN Collaborative Group (2009). Dentists in practice-based research networks have much in common with dentists at large: evidence from The Dental PBRN. Gen Dent 57:270–275 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejàre I, Sundberg H, Espelid I, Tveit B. (1999). Caries assessment and restorative treatment thresholds reported by Swedish dentists. Acta Odontol Scand 57:149–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejàre I, Stenlund H, Zelezny-Holmlund C. (2004). Caries incidence and lesion progression from adolescence to young adulthood: a prospective 15-year cohort study in Sweden. Caries Res 38:130–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2010). Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists: trends in the number of dentists. URL accessed on 9/25/2012 at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/ishi/10/dl/kekka_2.pdf

- No Authors Listed (2001). Diagnosis and management of dental caries throughout life. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement J Dent Educ 65:1162–1168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer KK, Donly KJ. (2004). Remineralization effects of a sodium fluoride bioerodible gel. Am J Dent 17:245–248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman BA, Drabick DA, Hershenberg R, Vivian D, Wolfe BE, Goldfried MR. (2012). Bridging the gap between clinical research and clinical practice: introduction to the special section. Psychotherapy (Chic) 49:97–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traebert J, Marcenes W, Kreutz JV, Oliveira R, Piazza CH, Peres MA. (2005). Brazilian dentists’ restorative treatment decisions. Oral Health Prev Dent 3:53–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tveit AB, Espelid I, Skodje F. (1999). Restorative treatment decisions on approximal caries in Norway. Int Dent J 49:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas MJ, Anusavice KJ, Frencken JE, Mount GJ. (2000). Minimal intervention dentistry—a review. FDI Commission Project 1-97. Int Dent J 50:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dorp CS, Exterkate RA, ten Cate JM. (1988). The effect of dental probing on subsequent enamel demineralization. ASDC J Dent Child 55:343–347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara A, Watanabe R, Hanada N, Miyazaki H. (2009). A longitudinal study of the relationship between diet intake and dental caries and periodontal disease in elderly Japanese subjects. Gerodontology 26:130–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]