Abstract

Background: Prior studies of α-linolenic acid (ALA), a plant-derived omega-3 (n−3) fatty acid, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk have generated inconsistent results.

Objective: We conducted a meta-analysis to summarize the evidence regarding the relation of ALA and CVD risk.

Design: We searched multiple electronic databases through January 2012 for studies that reported the association between ALA (assessed as dietary intake or as a biomarker in blood or adipose tissue) and CVD risk in prospective and retrospective studies. We pooled the multivariate-adjusted RRs comparing the top with the bottom tertile of ALA using random-effects meta-analysis, which allowed for between-study heterogeneity.

Results: Twenty-seven original studies were identified, including 251,049 individuals and 15,327 CVD events. The overall pooled RR was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.77, 0.97; I2 = 71.3%). The association was significant in 13 comparisons that used dietary ALA as the exposure (pooled RR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.81, 0.99; I2 = 49.0%), with similar but nonsignificant trends in 17 comparisons in which ALA biomarkers were used as the exposure (pooled RR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.63, 1.03; I2 = 79.8%). An evaluation of mean participant age, study design (prospective compared with retrospective), exposure assessment (self-reported diet compared with biomarker), and outcome [fatal coronary heart disease (CHD), nonfatal CHD, total CHD, or stroke] showed that none were statistically significant sources of heterogeneity.

Conclusions: In observational studies, higher ALA exposure is associated with a moderately lower risk of CVD. The results were generally consistent for dietary and biomarker studies but were not statistically significant for biomarker studies. However, the high unexplained heterogeneity highlights the need for additional well-designed observational studies and large randomized clinical trials to evaluate the effects of ALA on CVD.

INTRODUCTION

A large body of evidence supports a potential protective effect of seafood omega-3 (n−3) fatty acids, particularly EPA (20:5n−3) and DHA (22:6n−3), on coronary heart disease (CHD)4 (1). However, fewer studies have evaluated how the plant-derived omega-3 fatty acid α-linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3n−3) relates to risk of CHD and other cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes, and the results have been inconsistent (2–4). As an essential fatty acid that cannot be synthesized by humans, ALA is mainly consumed from plant sources, including soybeans, walnuts, and canola oil. Compared with seafood omega-3 fatty acids, ALA from plant sources is more affordable and widely available globally. Thus, whether ALA can reduce the risk of CVD is of considerable public health importance.

Mixed results of prior studies could partly relate to methods for assessment of ALA exposure. Several studies evaluated dietary ALA estimated from questionnaires, which could be influenced by measurement error, for example, because of imperfect participant recall or nutrient database information. In addition, dietary ALA is rapidly oxidized after digestion and has a low conversion rate to EPA/DHA (5, 6); thus, it is unclear whether the measurement of dietary ALA intake is an ideal metric to reflect the biologic effects of ALA in the human body. Other studies used biomarkers of ALA exposure, such as concentrations in blood or adipose tissue. Such measures are more objective than are dietary estimates, yet they may also reflect biologic processes related to ALA absorption, metabolism, and incorporation into different circulating and tissue lipid fractions rather than information on dietary intake alone (7).

Given the inconsistency of prior results and the potential for global impact of ALA on CVD outcomes, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence for the association between ALA exposure, including studies of dietary ALA and ALA biomarker concentrations, with risk of incident CVD.

METHODS

Literature search

We followed standard criteria for conducting and reporting meta-analyses of observational studies (8). We conducted systematic literature searches, from the index date of each database through January 2012, of multiple databases including PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed, since 1966), EMBASE (http://www.embase.com, since 1947), Web of Science (http://apps.webofknowledge.com, since 1956), the Cochrane Library (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/, since 1951), and clinical trial registry databases (http://clinicaltrials.gov, since 2000) for studies describing the association between ALA, assessed as dietary intake or biomarker, and incident CVD outcomes, including myocardial infarction (MI), ischemic heart disease, CHD, sudden cardiac arrest, acute coronary syndrome, and stroke. In addition, we searched the reference lists of all retrieved relevant articles and reviews. We restricted our searches to studies of humans, adults, and articles published in English. Our search terms combined the exposure (ALA) with various outcomes (CVD, type 2 diabetes, cancer, and total mortality); full details on the search strategy are presented elsewhere (see Supplemental Material under “Supplemental data” in the online issue). The current systematic review focused on CVD outcomes, and the other outcomes (type 2 diabetes, cancer, and total mortality), were examined separately.

Selection criteria

The articles were considered for inclusion if they 1) were original studies (eg, not review articles, meeting abstracts, editorials, or commentaries), 2) were prospective (eg, prospective cohort, nested case-control, case-cohort) or retrospective (eg, retrospective case-control, retrospective cohort) studies of noninstitutionalized adults >18 y of age, and 3) reported multivariate-adjusted risk estimates for the association between ALA, assessed as dietary intake or blood or adipose tissue concentrations, and at least one CVD outcome, including fatal or nonfatal CHD, ischemic heart disease, MI, sudden cardiac arrest, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, or composite endpoints. We also searched for randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials that evaluated the effects of ALA intake on primary prevention of CVD events; none were identified. Titles and abstracts of the identified studies were screened, and potentially relevant articles were selected for full-text review, which was performed independently by 2 investigators (AP and MC); any discrepancies were resolved by consensus or consultation with a third author (FBH).

Data extraction

For each identified article, 2 investigators (AP and MC) independently extracted information on study characteristics (citation, study name, authors, publication year), participant characteristics (location, number, mean age or age range, sex), ALA assessment (methods for assessing dietary consumption or biomarkers), CVD outcomes (specific endpoints, methods for diagnosis, follow-up years, duration), analysis strategy (statistical models, covariates), and multivariable-adjusted risk estimates, including data to calculate its precision, such as 95% CIs, SEs, or P values. Study quality was assessed on the basis of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (9), which involved evaluation of selection bias, comparability in study design and analysis, measurements of exposure and outcome, and generalizability of results. We defined studies of high or low quality based on the median overall score among all studies.

Data synthesis

The included studies reported RRs or HRs for prospective cohorts or ORs for case-control studies. HRs and ORs were assumed to approximate RRs. Individual studies reported risk estimates for ALA based on various categories (eg, tertiles, quartiles, quintiles, or specific thresholds), continuously in natural units (eg, 1 g/d for diet or 1% of total fatty acids for biomarkers), or per SD difference in exposure. To provide a consistent approach to meta-analysis, risk estimates for each study were transformed to involve comparisons between the top compared with the bottom tertiles of the population baseline distribution of ALA values by using methods previously described (10, 11). Briefly, log risk estimates were transformed with the comparison between top and bottom tertiles being equivalent to 2.18 times the log risk ratio for a 1-SD increase (10, 11). These scaling methods assume that the exposure is normally distributed and that the association with disease risk is log-linear. The conversion factor of 2.18 is the difference in the medians of the top and bottom thirds of the standard normal distribution; other conversions were used for differences in medians of extreme quartiles (2.54) or quintiles (2.80). The SEs of log RRs were calculated by using reported data on precision and were similarly standardized (10, 11). If one study had multiple eligible articles or one article reported multiple RRs, we extracted the RRs for the most specific coronary outcome event (according to the hierarchy: fatal CHD, nonfatal CHD, total CHD, and total CVD) with the largest number of adjustment variables.

Forest plots were produced to visually assess the RRs and corresponding 95% CIs across studies. Heterogeneity of RRs across studies was evaluated by using the I2 statistic (values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered to represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively). Summary RRs were calculated by pooling the inverse-variance weighted study-specific estimates by using DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models, which allowed for between-study heterogeneity; fixed-effects models were also evaluated when heterogeneity was <25%. The possibility of publication bias was evaluated by using the Begg's test and visual inspection of a funnel plot. Sources of heterogeneity, including exposure assessment (self-reported dietary consumption or biomarker concentrations), specific outcome (fatal and total CHD, fatal and total CVD, total stroke), study design (prospective compared with retrospective), age, sex, study quality, study location, and adjustment variables, were evaluated by using stratified analyses and univariate meta-regression method. We also tested the influence of individual study on the results in sensitivity analyses.

We further conducted a dose-response meta-analysis with the use of generalized least-squares regression (2-stage GLST in Stata) (12). GLST analyses were feasible for 2 exposure-outcome relations with sufficient data points: dietary ALA intake and risk of fatal CHD and adipose tissue ALA concentration and risk of nonfatal MI. All analyses were performed with Stata 11.0 (StataCorp), with a 2-tailed α of 0.05.

RESULTS

Literature search

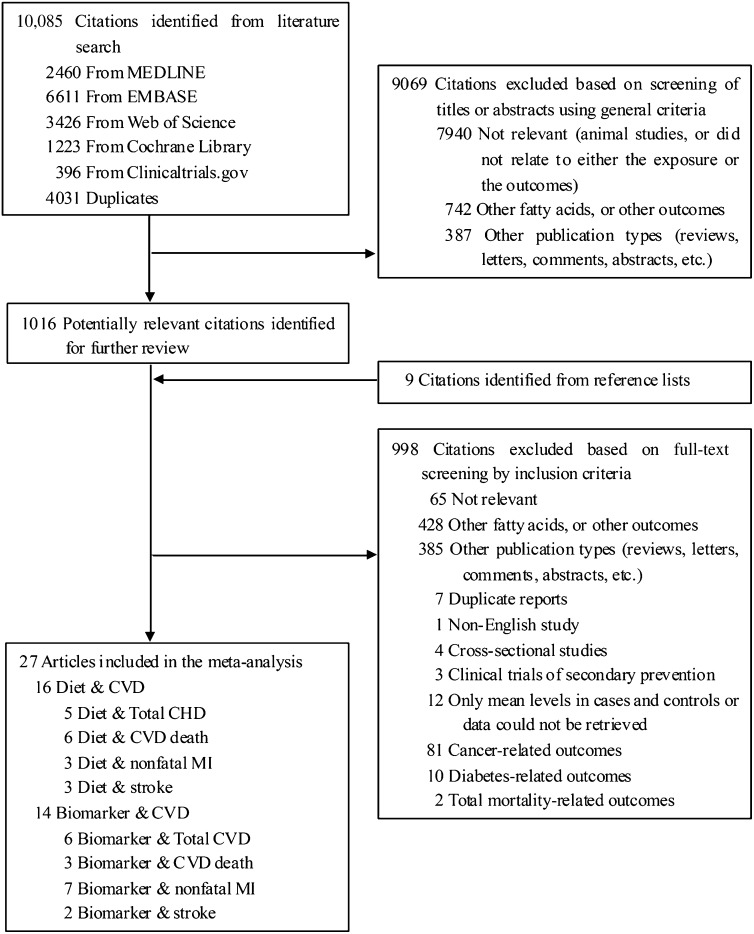

The search strategy identified 10,085 unique citations (Figure 1). After the titles and abstracts were screened, 1016 full-text articles were evaluated plus an additional 9 articles retrieved from reference lists, relevant reviews, and contacts with experts. After the final exclusions, 27 original articles were available and included in this meta-analysis, comprising a total of 251,049 individuals and 15,327 CVD events (13–39). A subset of studies reported results separately for CHD death (9 articles, 132,024 participants, 1859 cases) and stroke (5 articles, 100,915 participants, 3026 cases).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the meta-analysis. Three studies reported both diet and biomarker data. CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

Study characteristics

Among the 27 identified articles, 19 were prospective cohorts (including 4 nested case-control studies) and 8 were retrospective case-control studies (Table 1). Ten studies investigated associations of dietary ALA and CVD events, 14 studies investigated ALA biomarkers and CVD events, and 3 studies investigated both dietary ALA and ALA biomarkers and CVD events (37–39). The numbers of participants in each study ranged from 98 to 76,763, with follow-up durations (in cohort studies) ranging from 5 to 30.7 y. The studies were generally from the United States (n = 11) or European countries (n = 14); one study was based in Central America (39) and another in Israel (28). Nearly all (26 of 27) studies adjusted for traditional CVD risk factors (sociodemographics, comorbidites, lifestyle factors), and 14 studies further adjusted for other dietary intakes or biomarker concentrations of other fatty acids.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis1

| Reference | Study name and country | Total no. of participants (no. of cases) | Average follow-up duration | Study design | Male % | Baseline age | ALA measures | Baseline ALA concentration | Outcome | Adjustment |

| Dietary ALA intake as the exposure | ||||||||||

| Dolecek, 1992 (13) | The MRFIT study, United States | 6250 (232) | 10.5 y (1973–1985) | PC | 100 | Range: 35–57 y | Four 24-h dietary record (crude intake) | Mean2: 1.69 ± 0.74 g/d | CHD death | ++ |

| Ascherio et al, 1996 (14) | The HPFS study, United States | 43,757 (734) | 6 y (1986–1992) | PC | 100 | Range: 40–75 y | Validated FFQ (residual method adjusted) | Median: 1.1 g/d | Total MI, fatal MI | ++ |

| Pietinen et al, 1997 (15) | The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention study, Finland | 21,930 (1399) | 8 y (1985–1993); median: 6.1 y | PC | 100 | Range: 50–69 y | Dietary history (residual method adjusted) | Median: 1.5 g/d | Total MI, fatal MI | ++ |

| Hu et al, 1999 (16) | The NHS study, United States | 76,283 (829) | 10 y (1984–1994) | PC | 0 | Range: 38–63 y; mean: 50.3 y | Validated FFQ (residual method adjusted) | Mean: 1.10 ± 0.45 g/d | Fatal IHD | +++ |

| Oomen et al, 2001 (17) | Zutphen Elderly study, Netherlands | 667 (98) | 10 y (1985–1995) | PC | 100 | Range: 64–84 y; mean: 71.1 ± 5.2 y | Cross-check dietary history (percentage of energy) | Mean: 1.32 ± 0.47 g/d, or 0.53 ± 0.15% of total energy | CAD | +++ |

| He et al, 2002 (18) | The HPFS study, United States | 43,671 (608) | 12 y (1986–1998) | PC | 100 | Range: 40–75 y; mean: 53.4 y | Validated FFQ (residual method adjusted) | Mean: 1.07 g/d | Stroke | +++ |

| Albert et al, 2005 (19) | The NHS study, United States | 76,763 (2451) | 18 y (1984–2002) | PC | 0 | Range: 38–63 y; mean: 50.5 y | Validated FFQ (percentage of energy) | Median: 0.52% of total energy | Nonfatal MI | +++ |

| de Goede et al, 2011 (20) | The MORGEN study, Netherlands | 20,069 (581) | 13 y (1993/1997–2006); mean: 10.5 y | PC | 44.8 | Range: 20–65 y; mean: 41–42 y | Validated FFQ (residual method adjusted) | Mean: 1.3 ± 0.05 g/d | CHD, stroke | +++ |

| Vedtofte et al, 2011 (21) | Glostrup Population Studies, Denmark | 3277 (471) | Mean: 23.3 y | PC | 49.9 | Mean: 50.6 y | 7-d Weighted food records (crude intake) | Median: 1.2 g/d for women and 1.6 g/d for men | IHD | +++ |

| Larsson et al, 2012 (22) | Swedish Mammography Cohort, Sweden | 34,670 (1680) | Mean: 10.4 y | PC | 0 | Range: 49–83 y; mean: 61–62 y | Validated FFQ (residual method adjusted) | Median: 1.2 g/d | Stroke | +++ |

| ALA biomarker as the exposure | ||||||||||

| Simon et al, 1995 (23) | The MRFIT study, United States | 192 (96) | NA | NCC | 100 | Range: 35–57 y; mean: 50.3 ± 5.6 y | Serum CE and PL fatty acids | Mean: 0.39 ± 0.13% for CE and 0.12 ± 0.07% for PL in controls | Stroke | + |

| Simon et al, 1995 (24) | The MRFIT study, United States | 188 (94) | NA | NCC | 100 | Range: 35–57 y; mean: 49.8 ± 5.6 y | Serum CE and PL fatty acids | Mean: 0.40 ± 0.15% for CE and 0.14 ± 0.07% for PL in controls | CHD | + |

| Tornwall et al, 1996 (25) | The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention study, Finland | 670 (189) | NA | CC | 100 | Range: 50–69 y; mean: 58.1 y | Serum CE fatty acids | Mean: 0.68 ± 0.20% in controls | Acute MI | ++ |

| Guallar et al, 1999 (26) | The EURAMIC study, European countries and Israel | 1339 (639) | NA | CC | 100 | Range: ≤70 y; mean: 53.9 y | Adipose tissue | Mean: 0.80 ± 0.19% in controls | First-acute MI | +++ |

| Pedersen et al, 2000 (27) | Norway | 198 (100) | NA | CC | 72 | Range: 45–75 y; mean: 62.4 y | Adipose tissue | Mean: 0.71 ± 0.15% in controls | First-acute MI | +++ |

| Erkkila et al, 2003 (28) | Finnish cohort of the EUROASPIRE study, Finland | 398 (35) | 5 y (1995–2001) | PC | 68.7 | Range: 33–74 y; mean: 61 ± 8 y | Serum CE fatty acids | Median: 0.83% | Total CVD | ++ |

| Kark et al, 2003 (29) | Israel | 672 (180) | NA | CC | 72 | Range: 25–64 y; mean: 52.6 y | Adipose tissue | Mean: 1.23 ± 0.42% in controls | First-acute MI | +++ |

| Lemaitre et al, 2003 (30) | The CHS study, United States | 108 (54) | NA | NCC | 57.4 | Range: ≥65 y; mean: 78.5 y | Plasma PL fatty acids | Mean: 0.17 ± 0.06% in controls | Fatal IHD | ++ |

| Lemaitre et al, 2003 (30) | The CHS study, United States | 250 (125) | NA | NCC | 64 | Range: ≥65 y | Plasma PL fatty acids | Mean: 0.17 ± 0.06% in controls | Nonfatal MI | ++ |

| Wang et al, 2003 (31) | The ARIC study, United States | 3591 (282) | 12 y (1987/1989–1999); mean: 10.7 y | PC | 46 | Range: 45–64 y; mean: 54 y | Plasma CE and PL fatty acids | Median: 0.41% for CE and 0.14% for PL | Total CHD | ++ |

| Wiberg et al, 2006 (32) | The ULSAM study, Sweden | 2313 (421) | 32 y (1970/1972–2002); mean: 29.3 y | PC | 100 | Mean: 50 y | Serum CE fatty acids | Mean: 0.7 ± 0.2% | Stroke | ++ |

| Warensjö et al, 2008 (33) | The ULSAM study, Sweden | 2009 (1012) | 33.7 y (1970/1972–2003); mean: 30.7 y | PC | 100 | Mean: 50 y | Serum CE fatty acids | Mean: 0.66 ± 0.16% | CVD death | ++ |

| Lemaitre et al, 2009 (34) | United States | 680 (265) | NA | CC | 81 | Range: 25–74 y; mean: 57.6 y | Red blood cell membrane fatty acids | Mean: 0.13 ± 0.04% in controls | Sudden cardiac arrest | +++ |

| Shearer et al, 2009 (35) | United States | 898 (445) | NA | CC | 66.5 | Mean: 59 y | Red blood cell membrane fatty acids | Median: 0.44% in controls | Acute coronary syndrome | ++ |

| Khaw et al, 2012 (36) | EPIC-Norfolk study, United Kingdom | 7354 (2424) | NA | NCC | 52.2 | Mean: 61.6 y | Plasma PL fatty acids | Mean: 0.24% | Total CHD | +++ |

| Studies reporting both diet and biomarker results | ||||||||||

| Laaksonen et al, 2005 (37) | The KIHD study, Finland | 1551 (78) | 17.8 y (1984/1989–2001); median: 14.6 y | PC | 100 | Range: 42–60 y; mean: 52.0 ± 5.5 y | 4-d Food records (residual method adjusted); serum esterified fatty acids | Mean: 0.79 ± 0.23% for serum; 1.6 ± 0.5 g/d for diet | CVD death | +++ |

| Lopes et al, 2007 (38) | Portugal | 607 (297) | NA | CC | 100 | Range: ≥40 y; mean: 57.0 y | Validated FFQ (residual method adjusted); subset study of adipose tissue | Mean: 1.61 ± 0.59 g/d for diet; 0.36 ± 0.09% for adipose tissue in controls | First-acute MI | ++ |

| Campos et al, 2008 (39) | Costa Rica | 3638 (1819) | NA | CC | 73 | Mean: 58 ± 11 y | Adipose tissue and validated FFQ (residual method adjusted) | Mean: 1.63 ± 0.63 g/d for diet; 0.65 ± 0.21% for adipose tissue in controls | Nonfatal acute MI | +++ |

Degree of covariate adjustment indicated by +: sociodemographics (eg, age, sex, race, education, and income); ++: sociodemographics, other CVD risk factors (eg, BMI, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, family history, blood pressure, and blood lipids), and certain dietary variables (total energy, fiber intake etc., not including other fatty acids); +++: sociodemographics, other CVD risk factors, and dietary variables (including other fatty acids). ALA, α-linolenic acid; ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; CAD, coronary artery disease; CC, case-control study; CE, cholesterol ester; CHD, coronary heart disease; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CVD, cardiovascular disease; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer; EURAMIC, EURopean multicenter case-control study on Antioxidants, Myocardial Infarction and breast Cancer; EUROASPIRE, European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events; FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-Up Study; IHD, ischemic heart disease; KIHD, Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor; MI, myocardial infarction; MRFIT, Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial; MORGEN, Monitoring Project on Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases; NA, not available; NCC, nested case-control study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; PC, prospective cohort study; PL, phospholipids; ULSAM, Uppsala Longitudinal Study of Adult Men.

±SD (all such values).

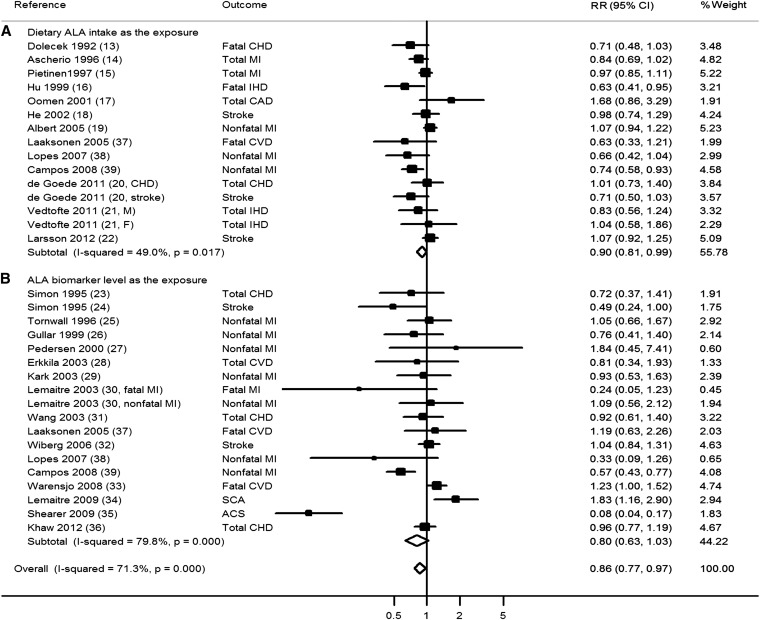

ALA and total CVD

A total of 33 comparisons reported the association between ALA and total CVD risk. The pooled RR for the comparison of the top with the bottom tertiles was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.77, 0.97; 15,327 events; Figure 2) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 71.3%). Heterogeneity appeared modestly lower for studies of dietary estimates (I2 = 49.0%) than for studies of ALA biomarkers (I2 = 79.8%). Restricted to dietary studies only, the pooled RR was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.81, 0.99; 11,277 events). Restricted to biomarker studies only, the pooled RR was generally similar (RR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.63, 1.03; 8555 events) but was not statistically significant. The meta-regression analysis did not identify statistically significant sources of this heterogeneity, including the mean age of the participants, sex composition, exposure measurement (diet compared with biomarker), disease outcomes, study design, study quality, or study design (all P > 0.10; see Supplemental Table 1 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue). The pooled RR appeared to be lower in studies from the United States and Costa Rica (RR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.57, 0.92) compared with pooled RR in studies from European countries (RR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.91, 1.08). However, the heterogeneity in studies from the United States and Costa Rica was high (I2 = 84.3%).

FIGURE 2.

RR of ALA intake and risk of total CVD stratified by dietary intake and biomarker concentration. The RRs were pooled by using random-effects meta-analysis. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ALA, α-linolenic acid; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IHD, ischemic heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; SCA, sudden cardiac arrest.

Visual inspection of a funnel plot (see Supplemental Figure 1 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue) and Begg's test did not indicate significant publication bias (P = 0.13). A sensitivity analysis testing the influence of individual study on the results suggested that one study (35) had the largest influence; after this study was excluded (35), the pooled RR was slightly attenuated (0.91; 95% CI: 0.83, 0.99) compared with that from the main analysis.

Among biomarker studies, 3 reported on both cholesterol ester and phospholipid ALA concentrations as the exposure (23, 24, 31). We used phospholipid ALA as the exposure in the primary analysis because phospholipids are the major class of lipids in membranes and small lipoproteins, and cholesterol ester composition may more likely be influenced by recently ingested fatty acids (7). A sensitivity analysis using results for cholesterol ester ALA rather than phospholipid ALA as the exposure in these 3 studies showed similar results, with a pooled RR of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.64, 1.05) for the association between ALA biomarker concentration and CVD risk and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.78, 0.98) for the association between overall ALA exposure and CVD risk.

Given concern that retrospective case-control studies may be limited by recall bias for dietary ALA and by reverse causation for biomarker ALA (blood biomarker influenced by disease status) (40), we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding retrospective case-control studies (n = 5). However, the case-control study using adipose tissue ALA concentration was included in the analysis, because the ALA concentration in adipose tissue may reflect a long-term exposure and was not immediately altered by the onset of CVD. The pooled RR was modestly attenuated to 0.91 (95% CI: 0.84, 1.00; 14,617 events); however, the I2 value was also reduced from 71.3% to 45.1% (see Supplemental Figure 2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue).

Several studies reported different CVD outcomes from the same population in different publications; thus, they were included more than once in the meta-analysis. To address the concern that the study weights may be inflated because of multiple counts, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to combine different CVD outcomes from the same parent study into a composite CVD outcome and then pooled the results from different studies in the second step. The pooled RR (0.85; 95% CI: 0.78, 0.93) from this sensitivity analysis was similar to that from the main analysis.

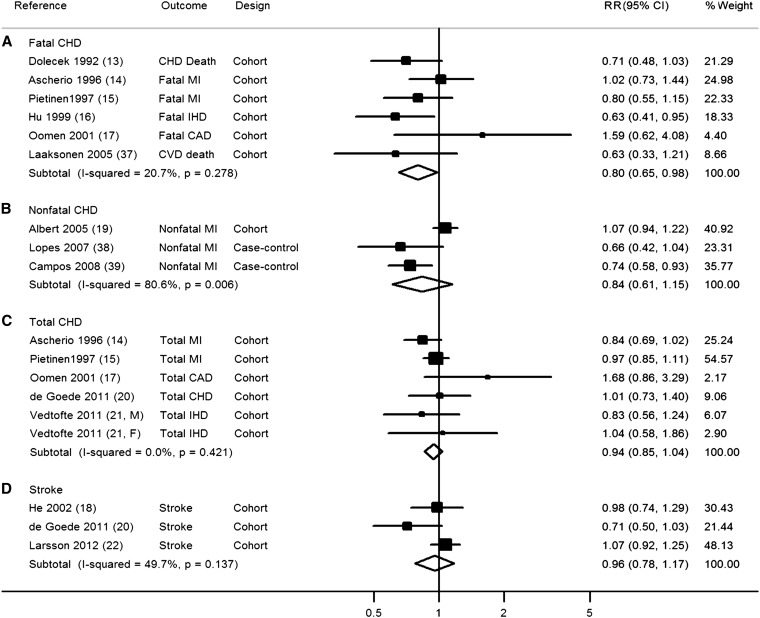

Dietary ALA and CVD subtypes

When we evaluated the relation of dietary ALA with risk of CVD subtypes, including fatal CHD, nonfatal CHD, total CHD, and stroke, the association was only statistically significant for dietary ALA and fatal CHD (pooled RR from 6 prospective cohort studies: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.65, 0.98; I2 = 20.7%; 1344 events; Figure 3). Nonsignificant trends were seen for some other CVD subtypes; however, generally, few studies were included in these subgroup analyses, and 95% CIs were broad.

FIGURE 3.

RR of dietary α-linolenic acid intake and risk of CVD stratified by specific disease outcomes. The RRs were pooled by using random-effects meta-analysis. CAD, coronary artery disease; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IHD, ischemic heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

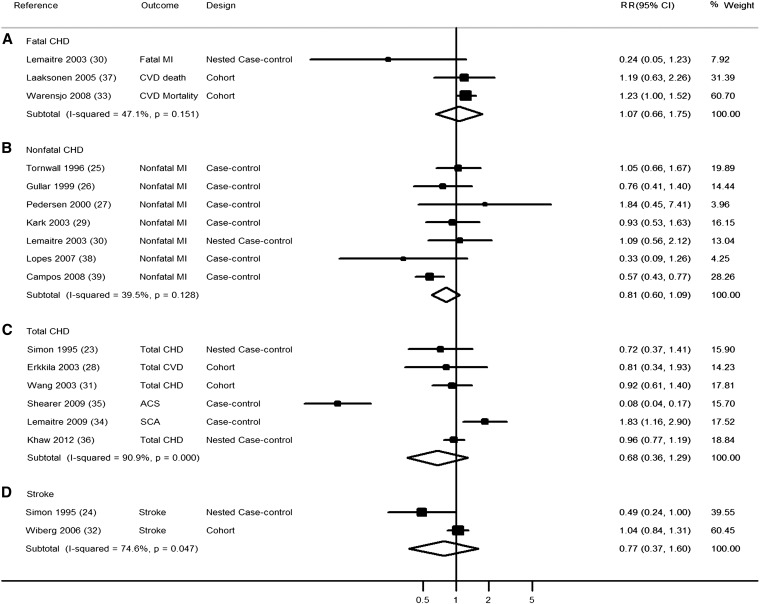

ALA biomarkers and CVD subtypes

When we evaluated the association of ALA biomarker concentrations with risk of CVD subtypes, none of the individual associations were statistically significant (Figure 4). However, substantial heterogeneity was observed for total CHD (I2 = 90.9%), and relatively few biomarker studies were available that evaluated fatal CHD (n = 3 studies; 593 events) or stroke (n = 2 studies; 517 events). Seven studies, 6 case-control and one nested case-control, investigated ALA biomarkers and nonfatal CHD. A comparison of the top with the bottom tertile in these 7 studies resulted in a pooled RR of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.60, 1.09; 3101 events) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 39.5%).

FIGURE 4.

RR of α-linolenic acid biomarker concentration and risk of CVD. The RRs were pooled by using random-effects meta-analysis. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; SCA, sudden cardiac arrest.

Dose-response meta-analyses

We evaluated potential dose-response associations using data from 5 prospective cohort studies of dietary ALA intake and risk of CHD death (1295 events) and 5 retrospective case-control studies of adipose ALA and risk of nonfatal MI (2787 events). Other exposure-disease relations were not evaluated in this analysis because of insufficient data points. In the pooled dietary analysis, each 1-g/d increment of ALA intake was associated with a 10% lower risk of CHD death (RR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.83, 0.99; see Supplemental Figure 3 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue). In the pooled biomarker analysis, each 0.5% increment of ALA concentration in adipose tissue was associated with a 23% nonsignificantly lower risk of nonfatal CHD (RR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.58, 1.01; see Supplemental Figure 3 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue).

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary and biomarker studies of ALA and CVD, we found that overall ALA exposure was associated with a modestly lower risk of CVD. Evaluation of subtypes of studies showed that dietary ALA was associated with a lower risk of CVD, particularly CHD death. The pooled risk estimate was generally similar for ALA biomarker concentrations, but the results were not statistically significant. Overall, these data support potential cardiovascular benefits of ALA. However, significant unexplained heterogeneity was seen, and there were too few studies that evaluated specific combinations of ALA exposure measurements (eg, diet, serum, plasma, phospholipids, cholesterol esters, and adipose tissue) and disease subtypes (eg, CHD death, nonfatal MI, and stroke) to evaluate potential causes of this heterogeneity.

In the past several decades, numerous studies have been conducted to identify potential beneficial effects of seafood omega-3 fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA, on cardiovascular outcomes. A meta-analysis of cohort studies and clinical trials suggested that daily consumption of 250 mg EPA/DHA reduced the risk of fatal CHD by 36% (41). Our meta-analysis suggests that ALA consumption may also confer cardiovascular benefits, and each 1 g/d increment of ALA intake was associated with a 10% lower risk of CHD death. Prior reviews evaluating ALA and CVD risk found only nonsignificant trends toward potential benefits (3, 4, 42). Our work considerably expands on these prior reviews by evaluating both dietary and biomarker studies and by including several recent investigations (20–22, 36).

Although nutrient biomarkers are generally considered superior to dietary estimates, the best exposure metric for ALA remains unclear. After consumption and absorption, ALA is extensively oxidized, and a very small proportion is converted to EPA (5, 6). Thus, the biomarker concentration of ALA in circulating blood compartments or adipose tissue may not strongly reflect dietary consumption (7). Rather, ALA concentrations in different tissues and lipid fractions may to a similar or even greater extent reflect various biologic pathways for metabolism and incorporation of ALA (7). Consistent with this, dietary estimates of ALA consumption do not correlate strongly with biomarker concentrations (average correlation of 0.35 for adipose tissue and 0.24 for blood concentrations) (7). Blood biomarker concentrations may also be limited in that they generally reflect exposures over the prior few weeks, rather than longer periods, which may be most relevant for risk of chronic diseases (7). On the other hand, self-reported estimates of ALA consumption are limited by measurement error because of imperfect participant recall and nutrient database information. Dietary ALA intakes were measured by different methods (food-frequency questionnaires, dietary history, and 4-d and 7-d dietary records) in various studies. Food-frequency questionnaires generally measure relatively long-term dietary habits, whereas 4-d and 7-d dietary records usually measure short-term dietary intakes. Dietary ALA data were also expressed in different formats (crude intake, energy adjusted by using the residual method, and percentage of energy). Furthermore, ALA comes from several dietary sources, including specific vegetable oils, nuts, spreading fats, soups, sauces, and even animal products (meat) (43), with potential heterogeneity of major sources between different populations. For instance, vegetable oil–containing margarines may be a major source of ALA in the Netherlands (44), whereas mayonnaise, creamy salad dressings, margarine, butter, and red meat may be major sources in the United States (45), and meats may be a nontrivial source in other nations (46). Overall, because of the different strengths and limitations of dietary compared with biomarker measures, the optimal measure for determining ALA exposure remains uncertain. A strength of our meta-analysis was that we evaluated both dietary and biomarker estimates, and the general similarity of the findings is reassuring.

Our findings support the need for further experimental and clinical studies to elucidate potential pathways of effects of ALA on CVD outcomes. Endogenous conversion of ALA to EPA is limited (<10%) and generally much lower in men than in women (47, 48). Whether ALA has beneficial effects beyond conversion to EPA remains unclear (49). Limited evidence suggests that ALA could have some independent role in cardiovascular health. Goyens et al (50) found that, among healthy elderly subjects, short-term ALA supplementation improved concentrations of LDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B more favorably than EPA/DHA supplementation. ALA and EPA/DHA may also share some common mechanisms, such as experimentally observed antiarrhythmic properties (51, 52), beneficial effects on thrombosis (53), and clinically observed improvement in endothelial function (54) and inflammatory factors (55). A direct or indirect antiarrhythmic effect of ALA could partially explain why ALA appeared protective against CHD death in our analysis. ALA intake is also correlated with the overall intakes of other PUFAs (ie, omega-6 fatty acids and EPA/DHA), which may provide beneficial effects on CVD. A previous investigation reported that the association between ALA intake and CHD risk was not influenced by background omega-6 fatty acids intake, but may be modified by EPA/DHA intake (56). Further studies are needed to investigate whether ALA has independent effects on cardiovascular health, or the effects can be modified by intake of other fatty acids.

Our findings highlight the need for an appropriately designed, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate the effects of dietary ALA on incidence of CVD. Very few prior clinical trials of ALA have been performed, and each with important limitations. In the Lyon Diet Heart Study (57), 605 post-MI patients were randomly assigned to a Mediterranean diet, including margarine supplemented with ALA (1.1 g/d), compared with a low-fat diet. Over a mean follow-up of 27 mo, the intervention group experienced a markedly lower incidence of CVD (RR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.12, 0.59), especially cardiac death (RR: 0.24; 95% CI: 0.07, 0.85); however, very few total events occurred (n = 41 CVD events), and the multicomponent nature of the dietary intervention makes it difficult to ascribe the benefits to ALA (54). A trial in India of an Indo-Mediterranean ALA-rich diet among 1000 patients with established CHD found similar results over a 1-y follow-up (58), but the interventions were not blinded and the validity of results from this group of investigators has been questioned (59). A larger double-blind, placebo-controlled trial among 4837 post-MI patients tested the effects on cardiovascular events of 400 mg EPA+DHA/d and/or 2 g ALA/d, by using a 2 × 2 factorial design. Because of fewer than expected events, ALA was not compared with placebo as originally planned, but rather with the factorial combination of EPA+DHA (50%) and placebo (50%). After a follow-up period of 40 mo, only a nonsignificant trend toward lower CVD risk was found for ALA (RR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.78, 1.05) compared with a combined control group receiving EPA+DHA or placebo (60). Additionally, this study was underpowered to detect an effect on CHD death, with only 17% power to detect a 25% reduction (1). Notably, all prior clinical trials were also secondary prevention interventions conducted among patients with established CHD, rather than primary prevention trials, which would most closely correspond to the observational studies of ALA and CVD risk in the present meta-analysis.

Several limitations should be considered. Our search was limited to English publications, and non-English or unpublished reports may exist. We identified large variations in study designs, methods for ALA measurement, covariate adjustments, and specific outcomes evaluated. Although we did not identify these variations as statistically significant sources of heterogeneity, such heterogeneity may limit the validity of the overall pooled results. Although all studies adjusted for major CVD risk factors and many adjusted for additional dietary or biomarker factors, residual confounding by imprecisely measured or unmeasured factors is possible.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis of both dietary and biomarker studies suggests that ALA exposure is associated with a moderately lower risk of CVD. Our findings suggest that ALA consumption may be beneficial and highlight the need for additional well-designed observational studies and randomized clinical trials to evaluate the effects of ALA on CVD risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Oscar Franco (Department of Epidemiology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands) for his comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—AP: researched the data, contributed to the discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript; MC and RC: researched the data, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed the manuscript; JHYW, QS, HC, and DM: contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript; FBH: researched the data, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript; and AP and FBH: had full access to the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed substantially to the conception and design or analysis and interpretation of the data and the drafting of the article or critical revision for important intellectual content. None of the funding sponsors was involved in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. FBH has received funding support from California Walnut Commission. None of the other authors had a conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: ALA, α-linolenic acid; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Wu JH. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2047–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brouwer IA, Katan MB, Zock PL. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid is associated with reduced risk of fatal coronary heart disease, but increased prostate cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Nutr 2004;134:919–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C, Harris WS, Chung M, Lichtenstein AH, Balk EM, Kupelnick B, Jordan HS, Lau J. N-3 fatty acids from fish or fish-oil supplements, but not alpha-linolenic acid, benefit cardiovascular disease outcomes in primary- and secondary-prevention studies: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:5–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geleijnse JM, de Goede J, Brouwer IA. Alpha-linolenic acid: is it essential to cardiovascular health? Curr Atheroscler Rep 2010;12:359–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdge GC, Calder PC. Conversion of alpha-linolenic acid to longer-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in human adults. Reprod Nutr Dev 2005;45:581–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arterburn LM, Hall EB, Oken H. Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n−3 fatty acids in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:1467S–76S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodson L, Skeaff CM, Fielding BA. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and blood in humans and its use as a biomarker of dietary intake. Prog Lipid Res 2008;47:348–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (cited 1 March 2012).

- 10.Chêne G, Thompson SG. Methods for summarizing the risk associations of quantitative variables in epidemiologic studies in a consistent form. Am J Epidemiol 1996;144:610–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danesh J, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R. Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA 1998;279:1477–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orsini N, Bellocco R, Greenland S. Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized dose-response data. Stata Journal 2006;6:40–57 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolecek TA. Epidemiological evidence of relationships between dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and mortality in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1992;200:177–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Spiegelman D, Stampfer M, Willett WC. Dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease in men: cohort follow up study in the united states. BMJ 1996;313:84–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pietinen P, Ascherio A, Korhonen P, Hartman AM, Willett WC, Albanes D, Virtamo J. Intake of fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease in a cohort of finnish men. The alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene cancer prevention study. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:876–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Wolk A, Colditz GA, Hennekens CH, Willett WC. Dietary intake of alpha-linolenic acid and risk of fatal ischemic heart disease among women. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:890–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oomen CM, Ocke MC, Feskens EJ, Kok FJ, Kromhout D. Alpha-linolenic acid intake is not beneficially associated with 10-y risk of coronary artery disease incidence: the Zutphen Elderly Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:457–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He K, Rimm EB, Merchant A, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Fish consumption and risk of stroke in men. JAMA 2002;288:3130–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert CM, Oh K, Whang W, Manson JE, Chae CU, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid intake and risk of sudden cardiac death and coronary heart disease. Circulation 2005;112:3232–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Goede J, Verschuren WM, Boer JM, Kromhout D, Geleijnse JM. Alpha-linolenic acid intake and 10-year incidence of coronary heart disease and stroke in 20000 middle-aged men and women in the netherlands. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e17967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vedtofte MS, Jakobsen MU, Lauritzen L, Heitmann BL. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid, linoleic acid, and n−3 long-chain PUFA and risk of ischemic heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1097–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson SC, Virtamo J, Wolk A. Dietary fats and dietary cholesterol and risk of stroke in women. Atherosclerosis 2012;221:282–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon JA, Hodgkins ML, Browner WS, Neuhaus JM, Bernert JT, Jr, Hulley SB. Serum fatty acids and the risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:469–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon JA, Fong J, Bernert JT, Jr, Browner WS. Serum fatty acids and the risk of stroke. Stroke 1995;26:778–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tornwall ME, Salminen I, Aro A, Pietinen P, Haukka J, Albanes D, Virtamo J. Effect of serum and dietary fatty acids on the short-term risk of acute myocardial infarction in male smokers. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 1996;6:73–80 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guallar E, Aro A, Jimenez FJ, Martin-Moreno JM, Salminen I, van't Veer P, Kardinaal AF, Gomez-Aracena J, Martin BC, Kohlmeier L, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in adipose tissue and risk of myocardial infarction: the EURAMIC study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:1111–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen JI, Ringstad J, Almendingen K, Haugen TS, Stensvold I, Thelle DS. Adipose tissue fatty acids and risk of myocardial infarction: a case-control study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2000;54:618–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erkkilä AT, Lehto S, Pyorala K, Uusitupa MI. n−3 fatty acids and 5-y risks of death and cardiovascular disease events in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kark JD, Kaufmann NA, Binka F, Goldberger N, Berry EM. Adipose tissue n−6 fatty acids and acute myocardial infarction in a population consuming a diet high in polyunsaturated fatty acids. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:796–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemaitre RN, King IB, Mozaffarian D, Kuller LH, Tracy RP, Siscovick DS. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, fatal ischemic heart disease, and nonfatal myocardial infarction in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:319–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Folsom AR, Eckfeldt JH. Plasma fatty acid composition and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle aged adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2003;13:256–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiberg B, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J, Terent A, Vessby B, Zethelius B, Lind L. Metabolic risk factors for stroke and transient ischemic attacks in middle-aged men: a community-based study with long-term follow-up. Stroke 2006;37:2898–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warensjö E, Sundstrom J, Vessby B, Cederholm T, Riserus U. Markers of dietary fat quality and fatty acid desaturation as predictors of total and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:203–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemaitre RN, Lemaitre RN, King IB, Sotoodehnia N, Rea TD, Raghunathan TE, Rice KM, Lumley TS, Knopp RH, Cobb LA, et al. Red blood cell membrane alpha-linolenic acid and the risk of sudden cardiac arrest. Metabolism 2009;58:534–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shearer GC, Pottala JV, Spertus JA, Harris WS. Red blood cell fatty acid patterns and acute coronary syndrome. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khaw KT, Friesen MD, Riboli E, Luben R, Wareham N. Plasma phospholipid fatty acid concentration and incident coronary heart disease in men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Study. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laaksonen DE, Nyyssonen K, Niskanen L, Rissanen TH, Salonen JT. Prediction of cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged men by dietary and serum linoleic and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:193–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopes C, Aro A, Azevedo A, Ramos E, Barros H. Intake and adipose tissue composition of fatty acids and risk of myocardial infarction in a male portuguese community sample. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:276–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campos H, Baylin A, Willett WC. Alpha-linolenic acid and risk of nonfatal acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2008;118:339–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kark JD, Manor O, Goldman S, Berry EM. Stability of red blood cell membrane fatty acid composition after acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:889–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA 2006;296:1885–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:659–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welch AA, Shakya-Shrestha S, Lentjes MA, Wareham NJ, Khaw K-T. Dietary intake and status of n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in a population of fish-eating and non-fish-eating meat-eaters, vegetarians, and vegans and the precursor-product ratio of α-linolenic acid to long-chain n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: results from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1040–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuurman AG, van den Brandt PA, Dorant E, Brants HA, Goldbohm RA. Association of energy and fat intake with prostate carcinoma risk: results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer 1999;86:1019–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Chute CC, Willett WC. A prospective study of dietary fat and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:1571–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Stéfani E, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Boffetta P, Ronco A, Mendilaharsu M. Alpha-linolenic acid and risk of prostate cancer: a case-control study in uruguay. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000;9:335–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burdge G. Alpha-linolenic acid metabolism in men and women: nutritional and biological implications. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2004;7:137–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Decsi T, Kennedy K. Sex-specific differences in essential fatty acid metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1914S–9S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris WS. Cardiovascular risk and α-linolenic acid. Circulation 2008;118:323–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goyens PL, Mensink RP. Effects of alpha-linolenic acid versus those of EPA/DHA on cardiovascular risk markers in healthy elderly subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006;60:978–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLennan PL, Dallimore JA. Dietary canola oil modifies myocardial fatty acids and inhibits cardiac arrhythmias in rats. J Nutr 1995;125:1003–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Billman GE, Kang JX, Leaf A. Prevention of sudden cardiac death by dietary pure ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in dogs. Circulation 1999;99:2452–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holy EW, Forestier M, Richter EK, Akhmedov A, Leiber F, Camici GG, Mocharla P, Luscher TF, Beer JH, Tanner FC. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid inhibits arterial thrombus formation, tissue factor expression, and platelet activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31:1772–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thies F, Miles EA, Nebe-von-Caron G, Powell JR, Hurst TL, Newsholme EA, Calder PC. Influence of dietary supplementation with long-chain n−3 or n−6 polyunsaturated fatty acids on blood inflammatory cell populations and functions and on plasma soluble adhesion molecules in healthy adults. Lipids 2001;36:1183–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rallidis LS, Paschos G, Liakos GK, Velissaridou AH, Anastasiadis G, Zampelas A. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid decreases c-reactive protein, serum amyloid a and interleukin−6 in dyslipidaemic patients. Atherosclerosis 2003;167:237–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mozaffarian D, Ascherio A, Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Siscovick DS, Rimm EB. Interplay between different polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Circulation 2005;111:157–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Lorgeril M, Renaud S, Salen P, Monjaud I, Mamelle N, Martin JL, Guidollet J, Touboul P, Delaye J. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet 1994;343:1454–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh RB, Dubnov G, Niaz MA, Ghosh S, Singh R, Rastogi SS, Manor O, Pella D, Berry EM. Effect of an Indo-Mediterranean diet on progression of coronary artery disease in high risk patients (Indo-Mediterranean Diet Heart Study): a randomised single-blind trial. Lancet 2002;360:1455–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mann J. The Indo-Mediterranean diet revisited. Lancet 2005;366:353–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kromhout D, Giltay EJ, Geleijnse JM. N–3 fatty acids and cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2015–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.