Abstract

Background: Adequate calcium intake is known to protect the skeleton. However, studies that have reported adverse effects of calcium supplementation on vascular events have raised widespread concern.

Objective: We assessed the association between calcium intake (from diet and supplements) and coronary artery calcification, which is a measure of atherosclerosis that predicts risk of ischemic heart disease independent of other risk factors.

Design: This was an observational, prospective cohort study. Participants included 690 women and 588 men in the Framingham Offspring Study (mean age: 60 y; range: 36–83 y) who attended clinic visits and completed food-frequency questionnaires in 1998–2001 and underwent computed tomography scans 4 y later in 2002–2005.

Results: The mean age-adjusted coronary artery–calcification Agatston score decreased with increasing total calcium intake, and the trend was not significant after adjustment for age, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, vitamin D–supplement use, energy intake, and, for women, menopause status and estrogen use. Multivariable-adjusted mean Agatston scores were 2.36, 2.52, 2.16, and 2.39 (P-trend = 0.74) with an increasing quartile of total calcium intake in women and 4.32, 4.39, 4.19, and 4.37 (P-trend = 0.94) in men, respectively. Results were similar for dietary calcium and calcium supplement use.

Conclusions: Our study does not support the hypothesis that high calcium intake increases coronary artery calcification, which is an important measure of atherosclerosis burden. The evidence is not sufficient to modify current recommendations for calcium intake to protect skeletal health with respect to vascular calcification risk.

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis and atherosclerosis are leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the Western world. Although these conditions commonly co-occur in older adults, growing evidence suggests an association between vascular calcification and skeletal fragility that is independent of age and other shared risk factors. Postmenopausal women with the greatest bone loss have the greatest progression of vascular calcification (1, 2), and the incidence of cardiovascular events is greater in women with lower bone mass (3) and in men with higher levels of bone resorption (4). Although previously thought to be a passive degenerative process, vascular calcification is now understood to be a highly regulated form of matrix mineral metabolism (5). Although pathogenic mechanisms involved in the bone-vascular axis are not yet fully elucidated (6), numerous factors have been implicated, including regulators of bone turnover, inflammatory cytokines (7–9), oxidized lipids (10, 11), osteoprotegerin and the receptor activator of nuclear factor kB ligand system (12, 13), vitamins D (14) and K (15), and others (16). An association between arterial calcification and skeletal fragility has significant clinical implications because strategies for prevention and therapy could potentially reduce the burden of both osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.

A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial designed to evaluate fracture outcomes showed, in a post hoc analysis, a 2-fold increased incidence of myocardial infarction over 7 y in women who took supplements of 1000 mg calcium citrate relative to a placebo (17). Although a mechanism is not yet defined, even a small, adverse effect of oral calcium on the vascular system could have major public health consequences because of the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease and wide use of calcium supplements. Coronary artery calcification is a strong predictor of cardiovascular disease, independent of the effects of established risk factors (18, 19). To help elucidate a potential mechanism by which oral calcium may affect risk of vascular disease, we performed an analysis to determine the association between baseline calcium intake from diet and supplements and the severity of coronary artery calcification evaluated 4 y later in a community-based study of women and men.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Participants are members of the Framingham Offspring Study (20), which includes a cohort enrolled in 1971 that comprised 5124 adult children and spouses of participants in the original Framingham Heart Study. The current study included 1201 Offspring cohort members, who attended a baseline clinic visit in 1998–2001 (exam 7) and underwent computed tomography (CT) examinations performed, on average, 4 y later in 2002–2005. Boston University Institutional Review Board approved the study, and participants provided written informed consent.

Information on clinical risk factors was obtained through a comprehensive physical examination, structured interview, and laboratory testing at the time of the baseline clinic visit. Diet and supplement use were assessed by using the Harvard food-frequency questionnaire (21). Information on participant age, smoking, alcohol consumption, menopausal status, use of osteoporosis medications (bisphophonate, selective estrogen-receptor modulator, and calcitonin), estrogen-replacement therapy (for women), lipid-lowering medications, antihypertensive agents, statins, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and aspirin use was obtained through a structured interview. Medication use (yes or no) was assessed as regular use in the past year. Individuals considered current smokers were those who reported smoking at least one cigarette per day in the past year. Alcohol consumption (oz/wk) was determined from the usual intake of beer, wine, and mixed drinks reported in the past year. A woman was classified as postmenopausal if she reported that menstrual periods had stopped for ≥1 y.

Height, to the nearest one-quarter inch, and weight, to the nearest one-half pound, were measured by using a stadiometer and balance-beam scale, respectively. BMI (in kg/m2) was calculated as weight divided by the square of height. Blood pressure (mm Hg) was measured twice, and the mean value of the 2 readings was used. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg or treatment with an antihypertensive agent. Type 2 diabetes was defined as a fasting plasma glucose concentration ≥126 mg/dL or treatment with insulin or an oral hypoglycemic agent. Coronary artery disease was defined as recognized or unrecognized myocardial infarction (identified by using an electrocardiogram or enzymes), angina pectoris, and coronary insufficiency. Cardiovascular disease included coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke (including transient ischemic attack), and intermittent claudication (22). These diagnoses were adjudicated by a 3-member panel of physicians who used standardized criteria and examined all available information including hospital records (23).

The concentration of plasma total cholesterol (mg/dL) was measured from fasting, morning blood samples by using an automated enzymatic assay procedure (24). HDL cholesterol and triglycerides were measured by using standard precipitation methods, and LDL cholesterol was calculated in subjects with triglyceride concentrations <400 mg/dL by using Friedewald's formula (25). The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated according to a simplified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation (26).

An 8-slice multidetector CT scanner (Lightspeed Ultra; General Electric Medical Systems) was used for cardiac imaging (27). Four experienced readers independently analyzed axial images, and the Agatston score was used to quantify coronary artery calcification. Correlation (r) was 0.96 for the agreement between Agatston scores for scan-rescan reliability based on 161 pairs of duplicate scans from a sample of participants (27).

We adjusted daily calcium (mg/d) and vitamin D intake (IU/d) for total energy by using a residual method suggested by Willett et al (21). ANCOVA was used to compare baseline characteristics according to sex-specific quartiles of energy-adjusted calcium intake. General linear regression models were used to estimate mean coronary artery–calcification Agatston scores and 95% CIs by quartiles of calcium intake with adjustment for covariates. Supplemental calcium was categorized into 3 groups as no use and ≤500 or >500 mg/d to ensure adequate numbers of individuals in each group for analysis. We compared mean Agatston scores between participants who either used or did not use any supplementary calcium (classified as yes or no). Because of a high frequency of Agatston scores of 0, we used the natural logarithm log (Agatston score + 1).

We constructed 3 hierarchical, multivariable-adjusted models. These models used total, dietary, or supplemental calcium as the primary independent variable of interest. The first multivariable model adjusted for age (y) and total energy (kcal). The second model adjusted as for the first model and for BMI, cigarette smoking (never, past, or current), alcohol consumption (oz/wk), energy-adjusted total vitamin D intake (including intake from supplements; IU), and, for women, menopause status (postmenopausal or premenopausal) and hormone replacement therapy (yes or no). The third multivariable model adjusted as for the second model and for diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (each yes or no), total cholesterol (mg/dL), and aspirin use (yes or no). In models with dietary calcium (mg) as the main effect, supplementary calcium (mg) was also included as a covariate. Conversely, in models with supplementary calcium (mg) as the main effect, energy-adjusted dietary calcium (mg) was included as a covariate.

We evaluated total energy-adjusted vitamin D intake and the GFR as potential confounders and effect modifiers by conducting stratified analysis (treating vitamin D and GFR as categorical variables) and multivariable analysis (constructing models with and without vitamin D and GFR). Finally, we repeated our analysis by excluding individuals with baseline cardiovascular disease because a potential effect of calcium intake on vascular calcification may differ between individuals with and without prevalent vascular disease. An analysis was conducted separately for women and men. We performed the analysis with SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Participants included 669 women and 532 men who ranged in age from 36 to 83 y, with a mean age of 60 y. Mean (±SD) (unadjusted) total calcium intake was 1185 ± 565 mg/d in women (760 mg from the diet and 425 mg from supplements) and 891 ± 461 mg/d in men (797 mg from the diet and 94 mg from supplements). Sixty-five percent of women and 25% of men took calcium supplements. Thirteen percent of women and 3% of men had intakes ≥1000 mg from supplements, and 7% of women and 2% of men had intakes ≥1200 mg from supplements.

Women in the highest quartile of energy-adjusted total calcium intake were slightly older, were more frequently postmenopausal, had lower BMI, had more favorable lipid concentrations and blood pressure, and were more likely to have used osteoporosis medications and estrogen-replacement therapy than were women in the lowest quartile (Table 1). Men in the highest quartile of total calcium intake had lower blood pressure and triglycerides than did men with lower calcium intake. The regular use of aspirin was more common in men in the highest quartile of calcium intake than in men in the lowest quartile of calcium intake. The prevalence of diabetes increased in men from 5% in the lowest quartile of calcium intake to 13% in the highest quartile of calcium intake (P-trend = 0.09), whereas no positive trend was seen in women. The use of antihypertensives, lipid-lowering medications, statins, and nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs did not vary by calcium intake in women or men.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants according to quartiles of energy-adjusted total calcium intake per day in the Framingham Offspring Study, 1998–20011

| Energy-adjusted total calcium intake quartiles 2 |

||||||||||

| Women |

Men |

|||||||||

| 1 (n = 167) | 2 (n = 167) | 3 (n = 168) | 4 (n = 167) | P-trend | 1 (n = 133) | 2 (n = 133) | 3 (n = 133) | 4 (n = 133) | P-trend | |

| Median (IQR) (mg) | 627 (141) | 917 (190) | 1305 (223) | 1845 (412) | — | 566 (103) | 722 (69) | 892 (106) | 1339 (436) | — |

| Range (mg) | 263–772 | 773–1127 | 1128–1557 | 1558–2821 | — | 8–652 | 653–803 | 804–1046 | 1047–3050 | — |

| Age (y) | 59 | 59 | 59 | 61 | 0.04 | 59 | 60 | 59 | 60 | 0.49 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | <0.01 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 28 | 0.25 |

| Current smoker (%) | 14 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 0.23 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 0.38 |

| Any alcohol consumption (%) | 64 | 58 | 63 | 59 | 0.51 | 83 | 79 | 70 | 76 | 0.07 |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 10 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0.34 | 5 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 0.09 |

| Hypertension (%) | 38 | 42 | 33 | 37 | 0.41 | 47 | 43 | 46 | 36 | 0.14 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0.37 | 5 | 12 | 3 | 10 | 0.66 |

| Cardiovascular disease (%) | 5 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 0.95 | 8 | 18 | 5 | 11 | 0.75 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 126 | 125 | 123 | 124 | 0.14 | 129 | 126 | 128 | 124 | 0.04 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 74 | 73 | 73 | 72 | 0.07 | 78 | 76 | 76 | 74 | 0.01 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 210 | 207 | 208 | 203 | 0.09 | 197 | 191 | 193 | 191 | 0.18 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 59 | 59 | 60 | 63 | 0.02 | 46 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 0.57 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 125 | 121 | 122 | 116 | 0.03 | 123 | 119 | 122 | 120 | 0.66 |

| Triglyceride cholesterol (mg/dL) | 132 | 136 | 127 | 118 | 0.04 | 151 | 147 | 132 | 130 | 0.03 |

| Antihypertensives (%) | 27 | 29 | 25 | 28 | 0.99 | 30 | 30 | 32 | 27 | 0.67 |

| Lipid-lowering medications (%) | 13 | 21 | 14 | 15 | 0.99 | 17 | 23 | 19 | 21 | 0.63 |

| Statins (%) | 13 | 20 | 14 | 13 | 0.73 | 17 | 21 | 17 | 23 | 0.47 |

| Aspirin use (%) | 23 | 25 | 29 | 24 | 0.64 | 31 | 35 | 39 | 47 | <0.01 |

| NSAIDs (%) | 28 | 34 | 31 | 30 | 0.85 | 35 | 29 | 20 | 29 | 0.28 |

| Osteoporosis medications (%) | 5 | 4 | 8 | 19 | <0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0.06 |

| Postmenopausal (%) | 83 | 80 | 84 | 92 | 0.01 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Estrogen use (%) | 34 | 35 | 38 | 42 | 0.09 | — | — | — | — | — |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Quartiles are numbered from the lowest (quartile 1) to highest (quartile 4).

The mean Agatston score was 125 ± 334 in women and 474 ± 814 in men and ranged from 0 to 3052 in women and from 0 to 5016 in men. Forty-three percent of women and 16% of men had no evidence of coronary calcification (Agatston score = 0), whereas an Agatston score ≥400 was 4 times more common in men (32%) than in women (8%).

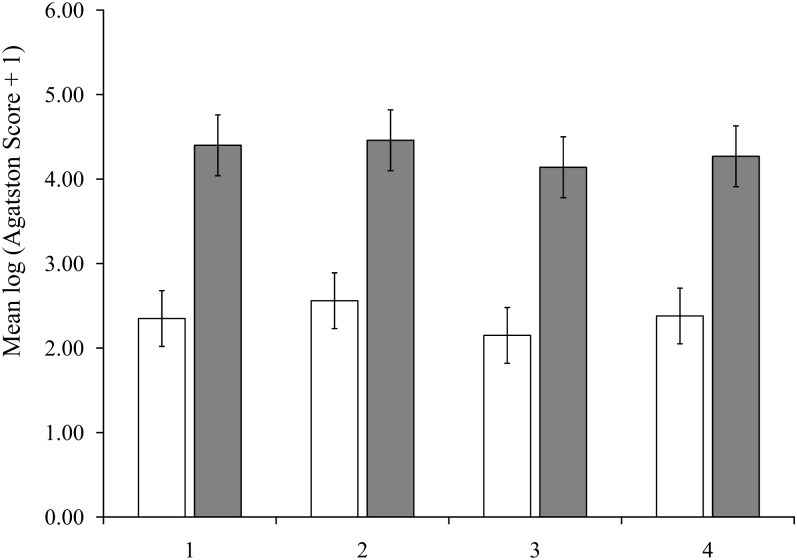

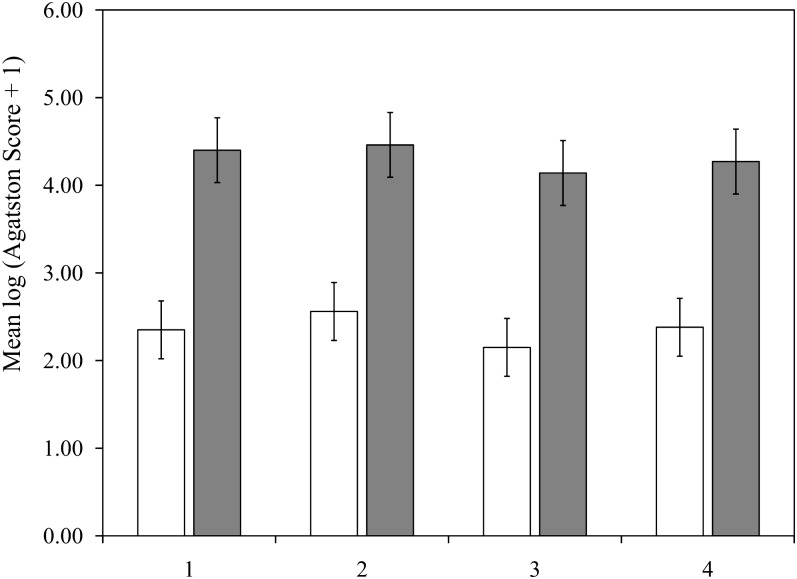

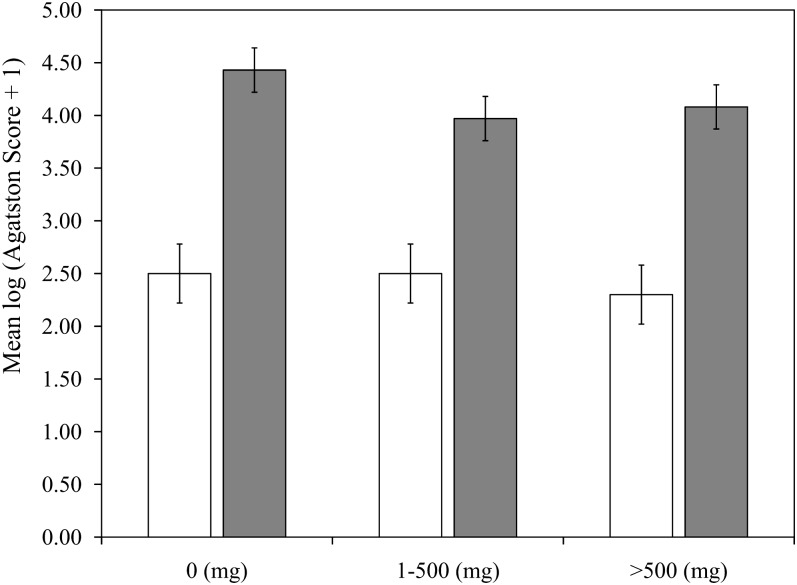

Mean Agatston scores, which were adjusted for age and energy, were similar across groups of total calcium intake (Figure 1) and dietary calcium intake (Figure 2) in women and men. Mean Agatston scores in women were 2.35 (95% CI: 2.03, 2.67), 2.56 (95% CI: 2.23, 2.88), 2.15 (95% CI: 1.82, 2.47), and 2.38 (95% CI: 2.05, 2.70) in the lowest to highest quartiles of total calcium, respectively (P-trend = 0.65) and 2.33 (95% CI: 2.00, 2.66), 2.28 (95% CI: 1.96, 2.61), 2.47 (95% CI: 2.14, 2.79), and 2.35 (95% CI: 2.02, 2.58), respectively, for dietary calcium (P-trend = 0.74). The findings in men also showed no effect of total or dietary calcium intake on Agatston scores, with P-trend values of 0.38 and 0.52 for total and dietary calcium, respectively. There were no significant linear trends between mean Agatston scores adjusted for age and energy and a higher intake of supplemental calcium in women (P = 0.31) or men (P = 0.07; Figure 3). Multivariable-adjusted mean Agatston scores were similar to age- and energy-adjusted values and were not associated with total, dietary, or supplementary calcium intake in women or men (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Mean (95% CI) coronary artery–calcification Agatston scores (2002–2005) adjusted for age and total energy according to total calcium intake quartile at baseline (1998–2001) in 690 women (open bars) and 588 men (filled bars) in the Framingham Offspring Study.

FIGURE 2.

Mean (95% CI) coronary artery–calcification Agatston scores (2002–2005) adjusted for age and total energy according to dietary calcium intake quartile at baseline (1998–2001) in 690 women (open bars) and 588 men (filled bars) in the Framingham Offspring Study.

FIGURE 3.

Mean (95% CI) coronary artery–calcification Agatston scores (2002–2005) adjusted for age and total energy according to supplemental calcium intake at baseline (1998–2001) in 690 women (open bars) and 588 men (filled bars) in the Framingham Offspring Study.

TABLE 2.

Multivariable-adjusted mean coronary artery–calcification Agatston score (2002–2005) according to quartiles of total, dietary, and supplemental calcium intake at baseline (1998–2001) in the Framingham Offspring Study1

| Log (Agatston score + 1) |

||

| Women | Men | |

| Total energy-adjusted calcium intake quartile | ||

| 1 | 2.36 (2.01, 2.71) | 4.32 (3.94, 4.70) |

| 2 | 2.52 (2.20, 2.84) | 4.39 (4.03, 3.75) |

| 3 | 2.16 (1.83, 2.48) | 4.19 (3.83, 4.55) |

| 4 | 2.39 (2.06, 2.73) | 4.37 (3.98, 4.75) |

| P-trend | 0.74 | 0.94 |

| Dietary energy-adjusted calcium intake quartile | ||

| 1 | 2.34 (2.01, 2.68) | 4.24 (3.87, 4.62) |

| 2 | 2.28 (1.96, 2.61) | 4.53 (4.17, 4.89) |

| 3 | 2.43 (2.10, 2.75) | 4.05 (3.69, 4.41) |

| 4 | 2.38 (2.05, 2.71) | 4.44 (4.07, 4.81) |

| P-trend | 0.74 | 0.92 |

| Supplemental calcium (mg/d) | ||

| 0 | 2.53 (2.24, 2.83) | 4.41 (4.20, 4.63) |

| 1–500 | 2.25 (1.96, 2.54) | 3.98 (3.54, 4.43) |

| >500 | 2.28 (1.98, 2.57) | 4.16 (3.37, 4.96) |

| P-trend | 0.46 | 0.21 |

All values are means; 95% CIs in parentheses. Model was adjusted for age (y) and total energy (kcal), BMI (kg/m2), smoking (never, past, or current), alcohol consumption (oz/wk), energy-adjusted total vitamin D intake (IU), and, for women, menopause status (postmenopausal or premenopausal) and hormone-replacement therapy (yes or no). In models with energy-adjusted dietary calcium as the main effect, supplementary calcium (mg) was included as a covariate. In models with supplementary calcium as the main effect, energy-adjusted dietary calcium (mg) was included as a covariate. Quartiles of total energy-adjusted calcium were as follows: quartile 1, ≤772 mg/d in women and ≤652 mg/d in men; quartile 2, 773–1127 mg/d in women and 653–803 mg/d in men; quartile 3, 1128–1557 in women and 804–1046 in men; and quartile 4, ≥1558 in women and ≥1047 in men. Quartiles of dietary energy-adjusted calcium were as follows: quartile 1, ≤408 mg/d in women and ≤587 mg/d in men; quartile 2, 409–550 mg/d in women and 588–721 mg/d in men; quartile 3, 551–714 mg/d in women and 722–896 mg/d in men; and quartile 4, ≥715 mg/d in women and ≥897 mg/d in men.

Additional adjustment for diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cholesterol, and aspirin use had little effect on results. Results were unchanged when we stratified by or adjusted for vitamin D intake or GFR. The exclusion of individuals with cardiovascular disease did not affect the findings. We performed an analysis in which coronary artery calcification was treated as a dichotomous outcome with individuals with any calcification (Agatston score ≥1) compared with individuals with no calcification (Agatston score = 0). Finally, we performed a Tobit analysis that was used for modeling outcome variables with floor effects, such as coronary artery calcification. Both of these approaches yielded similar findings.

DISCUSSION

In this community-based sample of women and men, baseline calcium intake from diet and supplements appeared to neither increase nor decrease vascular calcification, which is a measure of cardiovascular risk, after 4 y of follow-up. A lack of association with the Agatston score was consistent for total calcium intake (which ranged as high as 3000 mg/d), dietary calcium intake, and supplementary calcium intake, in both sexes. Consistent with our study, Wang et al (28) observed no effect of calcium treatment (600 or 1200 mg/d) on coronary calcium scores in 163 men (50% of subjects) and no effect of calcium treatment (1000 mg/d) on abdominal aortic calcification assessed by using lateral spine images from dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in 1471 women. Wang et al (28) did report that dietary calcium was inversely related to abdominal aortic calcification score at baseline in women but not in men (28), which is an observation that was not noted in the current study.

Vascular calcification is a highly regulated, active process with characteristics similar to bone formation (29, 30). Numerous cell types involved in bone turnover, including osteoblasts and osteoclasts, also participate in vascular calcification (31). Osteoclast-like cells have been shown in calcified arteries (12, 31). Many epidemiologic studies have shown an inverse association between various measures of bone health and vascular calcification (1, 2, 32, 33) and the incidence of cardiovascular outcomes (3, 4). The co-occurrence of calcium loss from the skeleton and deposition of calcium in the vasculature is far more complex than a simple transfer of calcium from bone to artery (34). The tight regulation of the calcium concentration in the blood argues against such a hypothesis of passive deposition. Although the knowledge of possible mechanisms shared in vascular and skeletal pathophysiology has significantly increased in the past 2 decades, our understanding in this area is not complete, particularly with respect to clinical implications (35, 36).

Although there are adverse effects of calcium supplementation on vascular calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease (37), the mechanism differs in adults with normal kidney function. Patients with chronic kidney disease, as well as those with diabetes, typically develop vascular calcification in the medial layers that causes arterial stiffness (38). In contrast, individuals with normal renal function tend to develop plaque calcification in the intima that causes reduced vascular compliance.

A potential role of calcium supplements in myocardial risk has created concern regarding the safety of calcium supplements for bone health (39, 40). However, in a recent report of recommendations for dietary reference intakes (41), the Institute of Medicine concluded that evidence from clinical trials currently does not support an effect of calcium intake on risk of cardiovascular disease. Although the discussion of methodologic issues of studies that reported an adverse effect of calcium supplements on cardiovascular events has been presented elsewhere (36, 42–44), some concerns include a lack of adjudicated endpoints, the undermining of random assignment, a low compliance with calcium supplements, and inadequate access to patient-level data.

Our study showed that calcium intake, whether from dietary or supplementary sources, was not associated with an increased coronary artery–calcification Agatston score. It is possible that calcium intake, particularly from supplements, was too low in participants to detect a potential effect. However, the highest quartile of total energy-adjusted calcium intake in our study ranged from 1558 to 2821 mg/d in women and from 1047 to 3050 mg/d in men, which are levels comparable to those of supplements in clinical trials of fracture outcomes and comparable to intakes in the general population for whom we wish to generalize our results.

Alternatively, the null results of our study may have been due to, in part, uncontrolled confounding in that participants with a high calcium intake may have been healthier (45) and, thereby, at lower risk of vascular calcification than were participants with a low calcium intake. We showed that some risk factors for vascular disease, such as increased BMI, smoking, hypertension, and coronary artery disease, were less frequent in women and men with high calcium intakes. However, the differences were not large, and in addition, adjustment for these factors did not change results. Also, information was available for a large number of confounders that were measured with a physical examination, laboratory testing, and the adjudication of diagnoses. Nonetheless, it is possible that a potential adverse association of calcium intake on vascular calcification could have been obscured by an inadequate control of confounders.

The assessment of diet is subject to error such that a nondifferential misclassification could have diluted an association between calcium intake and vascular calcification, particularly if the magnitude of the effect was small. Alternatively, the food-frequency questionnaire used in this study has been reproduced and validated for numerous nutrients in several populations (46–49), with a range of reliability from 64% to 79% for energy-adjusted calcium intake (50–52).

The use of calcium supplements is important for many older adults to ensure adequate intake for bone health. Current recommendations range from 1000 to 1200 mg Ca/d for adults aged ≥50 y (53). Adequate calcium intake has also been proposed as potentially beneficial for nonskeletal outcomes, including the prevention of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and vascular diseases (54, 55).

Our prospective study in a large, community-based population of women and men evaluated the relation between calcium intake, with an upper range as high as 3000 mg/d, on a specific measure of the presence and severity of coronary atherosclerosis (ie, coronary artery calcification), which is an independent predictor of cardiovascular events. We used state-of-the-art CT measures of coronary artery calcification, and we were able to take into account important factors in a study of calcium intake and vascular calcification such as vitamin D intake, prevalent coronary artery disease, and kidney function. Our results do not support a significant detrimental effect of calcium intake on coronary artery calcification.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—EJS: designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; SLB, CSF, KLT, TJW, UH, LAC, and CJO: contributed to writing the manuscript; and DPK: designed the research and contributed to writing the manuscript. EJS has received grants from Amgen related to studies of vascular calcification. TJW has provided consulting to and received honoraria and research support from Diasorin Inc. DPK has received grants from Amgen related to studies of vascular calcification and from Lilly and Merck to conduct clinical trials of osteoporosis that involved the administration of calcium supplements. SLB, CSF, KLT, UH, LAC, and CJO had no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hak AE, Pols HA, van Hemert AM, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Progression of aortic calcification is associated with metacarpal bone loss during menopause: a population-based longitudinal study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;20:1926–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiel DP, Kauppila LI, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, O'Donnell CJ, Wilson PW. Bone loss and the progression of abdominal aortic calcification over a 25 year period: the Framingham Heart Study. Calcif Tissue Int 2001;68:271–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samelson EJ, Kiel DP, Broe KE, Zhang Y, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, Wilson PW, Levy D, Williams SA, Vaccarino V. Metacarpal cortical area and risk of coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:589–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szulc P, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP, Delmas PD. Increased bone resorption is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events in men: the MINOS study. J Bone Miner Res 2009;24:2023–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson B, Towler DA. Arterial calcification and bone physiology: role of the bone-vascular axis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012;8:529–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Towler DA. Skeletal anabolism, PTH, and the bone-vascular axis. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26:2579–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shioi A, Katagi M, Okuno Y, Mori K, Jono S, Koyama H, Nishizawa Y. Induction of bone-type alkaline phosphatase in human vascular smooth muscle cells: roles of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and oncostatin M derived from macrophages. Circ Res 2002;91:9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tintut Y, Patel J, Parhami F, Demer LL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promotes in vitro calcification of vascular cells via the cAMP pathway. Circulation 2000;102:2636–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson KE, Bostrom K, Ravindranath R, Lam T, Norton B, Demer LL. TGF-beta 1 and 25-hydroxycholesterol stimulate osteoblast-like vascular cells to calcify. J Clin Invest 1994;93:2106–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parhami F, Morrow AD, Balucan J, Leitinger N, Watson AD, Tintut Y, Berliner JA, Demer LL. Lipid oxidation products have opposite effects on calcifying vascular cell and bone cell differentiation. A possible explanation for the paradox of arterial calcification in osteoporotic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997;17:680–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demer LL. Vascular calcification and osteoporosis: inflammatory responses to oxidized lipids. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:737–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucay N, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR, Morony S, Tarpley J, Capparelli C, Scully S, Tan HL, Xu W, Lacey DL, et al. Osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev 1998;12:1260–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collin-Osdoby P. Regulation of vascular calcification by osteoclast regulatory factors RANKL and osteoprotegerin. Circ Res 2004;95:1046–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raisz LG. Recent advances in bone cell biology: interactions of vitamin D with other local and systemic factors. Bone Miner 1990;9:191–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jie KG, Bots ML, Vermeer C, Witteman JC, Grobbee DE. Vitamin K status and bone mass in women with and without aortic atherosclerosis: a population-based study. Calcif Tissue Int 1996;59:352–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson RC, Leopold JA, Loscalzo J. Vascular calcification: pathobiological mechanisms and clinical implications. Circ Res 2006;99:1044–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolland MJ, Barber PA, Doughty RN, Mason B, Horne A, Ames R, Gamble GD, Grey A, Reid IR. Vascular events in healthy older women receiving calcium supplementation: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;336:262–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellasi A, Lacey C, Taylor AJ, Raggi P, Wilson PW, Budoff MJ, Vaccarino V, Shaw LJ. Comparison of prognostic usefulness of coronary artery calcium in men versus women (results from a meta- and pooled analysis estimating all-cause mortality and coronary heart disease death or myocardial infarction). Am J Cardiol 2007;100:409–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vliegenthart R, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Oei HH, van Dijck W, van Rooij FJ, Witteman JC. Coronary calcification improves cardiovascular risk prediction in the elderly. Circulation 2005;112:572–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feinleib M, Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. The Framingham Offspring Study. Design and preliminary data. Prev Med 1975;4:518–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willett WC, Sampson L, Browne ML, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. The use of a self-administered questionnaire to assess diet four years in the past. Am J Epidemiol 1988;127:188–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kannel WWP, Garrison R. The Framingham Study, section 35. Survival following initial cardiovascular events. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1998.

- 23.Abbott RDMD. The Framingham Study: An epidemiologic investigation of cardiovascular disease, Section 37: the probability of developing certain cardiovascular diseases in eight years at specified values of some characteristics. Bethseda, MD. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1987.

- 24.McNamara JR, Schaefer IJ. Automated enzymatic standardized lipid analyses for plasma and lipoprotein fractions. Clin Chim Acta 1987;166:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:461–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann U, Siebert U, Bull-Stewart A, Achenbach S, Ferencik M, Moselewski F, Brady TJ, Massaro JM, O'Donnell CJ. Evidence for lower variability of coronary artery calcium mineral mass measurements by multi-detector computed tomography in a community-based cohort–consequences for progression studies. Eur J Radiol 2006;57:396–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang TK, Bolland MJ, Pelt NC, Horne AM, Mason BH, Ames RW, Grey AB, Ruygrok PN, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Relationships between vascular calcification, calcium metabolism, bone density and fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25:2777–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demer LL. A skeleton in the atherosclerosis closet. Circulation 1995;92:2029–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tintut Y, Demer LL. Recent advances in multifactorial regulation of vascular calcification. Curr Opin Lipidol 2001;12:555–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doherty TM, Uzui H, Fitzpatrick LA, Tripathi PV, Dunstan CR, Asotra K, Rajavashisth TB. Rationale for the role of osteoclast-like cells in arterial calcification. FASEB J 2002;16:577–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farhat GN, Cauley JA, Matthews KA, Newman AB, Johnston J, Mackey R, Edmundowicz D, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Volumetric BMD and vascular calcification in middle-aged women: The study of women's health across the nation. J Bone Miner Res 2006;21:1839–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyder JA, Allison MA, Wong N, Papa A, Lang TF, Sirlin C, Gapstur SM, Ouyang P, Carr JJ, Criqui MH. Association of coronary artery and aortic calcium with lumbar bone density: the MESA Abdominal Aortic Calcium Study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:186–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abedin M, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Vascular calcification: mechanisms and clinical ramifications. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:1161–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Towler DA. Vascular calcification: a perspective on an imminent disease epidemic. IBMS BoneKEy 2008;5:41–58 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hennekens CH, Barice EJ. Calcium supplements and risk of myocardial infarction: a hypothesis formulated but not yet adequately tested. Am J Med 2011;124:1097–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West SL, Swan VJ, Jamal SA. Effects of calcium on cardiovascular events in patients with kidney disease and in a healthy population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5(suppl 1):S41–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao JS, Cheng SL, Sadhu J, Towler DA. Inflammation and the osteogenic regulation of vascular calcification: a review and perspective. Hypertension 2010;55:579–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, Grey A, MacLennan GS, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011;342:d2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Gallagher JC, Gallo RL, Jones G, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:53–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nordin BE, Lewis JR, Daly RM, Horowitz J, Metcalfe A, Lange K, Prince RL. The calcium scare–what would Austin Bradford Hill have thought? Osteoporos Int 2011;22:3073–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, Grey A, Reid IR, MacLennan GS, Gamble GD. Calcium and heart attacks reply. BMJ 2010;341:d4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Grey A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Calcium, vitamin D, and risk authors’ reply. BMJ 2011;342:d3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radimer K, Bindewald B, Hughes J, Ervin B, Swanson C, Picciano MF. Dietary supplement use by US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:339–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc 1993;93:790–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longnecker MP, Lissner L, Holden JM, Flack VF, Taylor PR, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. The reproducibility and validity of a self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire in subjects from South Dakota and Wyoming. Epidemiology 1993;4:356–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1114–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 1985;122:51–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munger RG, Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Kaye SA, Sellers TA. Dietary assessment of older Iowa women with a food frequency questionnaire: nutrient intake, reproducibility, and comparison with 24-hour dietary recall interviews. Am J Epidemiol 1992;136:192–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jain M, Howe GR, Rohan T. Dietary assessment in epidemiology: comparison on food frequency and a diet history questionnaire with a 7-day food record. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:953–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, McIntosh A, Rosenfeld S. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:1089–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Major GC, Alarie F, Dore J, Phouttama S, Tremblay A. Supplementation with calcium + vitamin D enhances the beneficial effect of weight loss on plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:54–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elwood PC, Strain JJ, Robson PJ, Fehily AM, Hughes J, Pickering J, Ness A. Milk consumption, stroke, and heart attack risk: evidence from the Caerphilly cohort of older men. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:502–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]