Abstract

Objective

To identify factors that influence medical students’ choice of family medicine versus another specialty and to analyze influential factors by urban versus rural background of students.

Design

Cross-sectional questionnaire survey conducted in 2010.

Setting

University of Alberta in Edmonton.

Participants

A total of 118 first-, 120 second-, and 107 third-year medical students.

Main outcome measures

Twenty-two factors influencing preferred career choice, type of community lived in (rural vs urban), and student age and sex.

Results

Overall, 283 (82.0%) students responded to the survey. Those who preferred family medicine rather than another specialty as a career option were older (≥ 25 years) (69.6% vs 40.9%, P < .001), female (69.6% vs 39.3%, P < .001), and had previously lived in rural locations (< 25 000 population) (46.8% vs 23.9%, P < .001). Four factors were significantly associated with students preferring family medicine compared with any other specialty: emphasis on continuity of care (87.3 vs 45.3%, P < .001); length of residency (73.4% vs 25.9%, P < .001); influence of family, friends, or community (67.1% vs 50.2%, P = .011); and preference for working in a rural community (41.8% vs 10.9%, P < .001). For students with urban backgrounds, the preference for family medicine was more strongly influenced by the opportunity to deal with a variety of medical problems; current debt load; and family, friends, or community than for those with rural backgrounds. Practice location preferences also differed between students from rural and urban backgrounds.

Conclusion

Medical students who prefer family medicine as a career choice appear to be influenced by a different set of factors than those who prefer other specialties. Being female; being older; having previously lived in a rural location; placing importance on continuity of care; desire for a shorter residency; and influence of family, friends, or community are associated with medical students preferring family medicine. Some differences in factors influencing career choice exist between medical students from rural versus urban backgrounds. To increase the supply of family physicians, medical schools might consider introducing elements into the admissions process and the medical curriculum that encourage family medicine as a career choice.

Résumé

Objectif

Identifier les facteurs qui font en sorte que les étudiants en médecine choisissent la médecine familiale plutôt qu’une autre spécialité et analyser ces facteurs en fonction de l’origine urbaine ou rurale des étudiants.

Type d’étude

Enquête transversale par questionnaire effectuée en 2010.

Contexte

L’Université de l’Alberta à Edmonton.

Participants

Étudiants en médecine des première (n = 118), deuxième (n = 120) et troisième années (n = 107).

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Vingt-deux facteurs qui influencent le choix de carrière, le type de communauté habitée (rurale ou urbaine), et l’âge et le sexe des étudiants.

Résultats

En tout, 283 étudiants ont répondu à l’enquête (82 %). Ceux qui préféraient la médecine familiale plutôt qu’une autre spécialité comme carrière éventuelle étaient plus âgés (25 ans) (69,6 % vs 40,9 %, P < ,001), étaient des femmes (69,6 % vs 39,3 %, P < ,001) et avaient auparavant vécu en milieu rural (population < 25 000) (46,8 % vs 23,9 %, P < ,001). Quatre facteurs présentaient une association significative avec la préférence des étudiants pour la médecine familiale plutôt qu’une autre spécialité : emphase placée sur la continuité des soins (87,3 vs 45,3 %, P < ,001); durée de la résidence (73,4 vs 25,9 %, P < ,001); influence de la famille, des amis ou de la communauté (67,1 vs 50,2 %, P = ,011); et préférence pour pratiquer dans une communauté rurale (41,8 vs 10,9 %, P < ,001). Chez les étudiants venant d’un milieu urbain, le fait de préférer la médecine familiale était plus fortement influencé par l’occasion de traiter une grande variété des problèmes médicaux, par le niveau actuel de leur dette, et par leur famille, amis et communauté que chez leurs collègues d’origine rurale. De plus, la préférence pour le lieu de pratique n’était pas la même pour les étudiants d’origine rurale et ceux d’origine urbaine.

Conclusion

Les étudiants en médecine qui envisagent de faire carrière en médecine familiale semblent influencés par un ensemble de facteurs différents de ceux qui influences les étudiants qui envisagent d’autres spécialités. Il y a une association entre être une femme, être plus âgé, avoir déjà vécu en milieu rural, attribuer de l’importance à la continuité des soins, désirer une résidence plus courte, et subir l’influence de la famille, des amis et de la communauté, et le fait de préférer la médecine familiale. Il existe certaines différences entre les étudiants d’origine rurale et ceux d’origine urbaine pour ce qui est des facteurs qui influencent le choix de carrière. Afin d’augmenter le nombre de médecins de famille, les facultés de médecine devraient envisager d’introduire dans leurs critères d’admission et dans le cursus médical des éléments qui favorisent de choix d’une carrière en médecine familiale.

For well over 20 years, there has been concern about a shortage of family physicians in Canada.1 Various strategies have been tried to address this problem,2 including medical education initiatives aimed at increasing the number of medical students who choose family medicine as a career option. Despite these efforts, there has been a declining interest in family medicine. In 1982, 40% of graduating medical students chose family medicine as a career option; only 32% selected it as their first choice in the 2010 Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) match, with as few as 23% choosing family medicine in some schools.3 This phenomenon is not unique to Canada, as other nations report similar declines.4–6 Reversal of this trend will require a better understanding of the complex array of factors that influences medical students’ choice of career.

By far most research findings on factors affecting medical students’ career choice are identified in the framework outlined by Bland et al.7 Student characteristics that have been reported as being predictive of medical students preferring family medicine or a primary care specialty include older age,8–10 female sex,9,11,12 non-single marital status,8,13,14 having a rural background,9,15 and not having parents with postgraduate university education.8 In terms of personal values, various studies have found that students who select family medicine as a career choice are more likely to have a societal orientation,8,14,16,17 possess attitudes favouring helping people over seeking opportunities for leadership,9 have a desire for intellectual challenge,9 and have volunteered in a developing country.8 In addition, students who choose family medicine also tend to desire a shorter postgraduate training period8 and are concerned about medical lifestyle.18,19 Students who choose a specialty career tend to be more influenced by prestige, income, opportunities for research, and faculty status.13,15,16

Knowledge of factors that influence medical students’ career choice can inform educators and policy makers regarding strategies to increase interest in family medicine and the supply of family physicians. To further advance the understanding of factors influencing career choice and to add current data to the existing body of research, we surveyed first-, second-, and third-year medical students. Given that rural background is associated with increased interest in family medicine,9 an examination of factors that influence career choices of students from rural backgrounds might provide insight into ways to increase the general appeal of family medicine. The purpose of this study was to examine factors that influence medical students’ career choice of family medicine versus specialty medicine and to analyze factors by rural versus urban background.

METHODS

Design and sample

A cross-sectional questionnaire survey of first-, second-, and third-year medical students at the University of Alberta in Edmonton was conducted during May 2010. The total population (N = 489) included 189 first-year, 156 second-year, and 144 third-year medical students.

Study setting

Undergraduate medical education at the University of Alberta encompasses 4 years. The first and second years are preclinical in nature and consist of organ-system blocks, patient-centred health, and community health. Third and fourth years are clinical clerkship years. During third year, students complete 6 core rotations in medicine, surgery, family medicine (4 weeks each in rural and urban areas), pediatrics, psychiatry, and obstetrics and gynecology, as well as elective experiences. A small group of third-year students complete their rotations in rural communities as part of the Integrated Community Clerkship program. Fourth-year students take part in sub-specialty medicine and surgery electives, as well as rotations in emergency medicine and geriatrics.

Study procedures

The survey was conducted in the classroom setting, either before or after class instruction. The study was explained to the students by an impartial individual who had no affiliation with the students. This individual explained the study, answered any questions, and collected completed questionnaires. The survey package contained a study information letter, a questionnaire, and a return envelope. To ensure confidentiality, completed questionnaires were returned in a sealed envelope and placed in a survey box in the classroom. Students also had the option of returning completed questionnaires by mail. All questionnaires were anonymous, such that no personally identifiable information was collected. The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board (Health Panel) at the University of Alberta.

Survey questionnaire

The questionnaire addressed 3 main areas: factors influencing preferred specialty choice; factors influencing desired location of future medical practice; and demographic information. Demographic characteristics included sex, age, year of medical school, marital status, ethnicity, financing of medical education, and if a parent was a physician. Students were asked to rate how important they perceived each of 22 factors to be in influencing their current preferred specialty using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unimportant) to 5 (very important). The factors influencing preferred career choice were based on an exit survey developed by the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Alberta. The list of medical career choices was adapted from the list used by CaRMS.3 Rural background was defined as having ever lived in a rural community of fewer than 25 000 people and an urban background was living in communities of 25 000 or more people. By definition, the urban background group had lived only in urban areas; those in the rural background group had to have lived in a rural area for some period of time. A population of 25 000 was used as the cutoff for rural background in order to include all small- and medium-sized rural communities and exclude all regional and metropolitan communities in Alberta (and most throughout Canada).

Data analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows and were primarily descriptive in nature, with frequency distributions and percentages. The χ2 test was used to test for relationships between discrete variables. An α level of .05 was used to test for statistical significance.

Career choice was classified as one of family medicine, emergency medicine, surgical specialty (cardiac surgery, general surgery, neurosurgery, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, or urology), or medical specialty (anatomic pathology, anesthesiology, community medicine, dermatology, diagnostic radiology, internal medicine, laboratory medicine, medical biochemistry, medical genetics, medical microbiology, neurology, neuropathology, nuclear medicine, pediatrics, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychiatry, radiation oncology, or other).

For the purposes of analysis, the rating scale was grouped into important (somewhat important and very important) or not important (very unimportant, somewhat unimportant, and neither unimportant nor important).

RESULTS

Respondents

The overall response rate was 82.0% (283 of 345), calculated as the total number of completed surveys divided by the total number of distributed surveys. The response rates were 75.4% (89 of 118), 91.7% (110 of 120), and 78.5% (84 of 107) for first-, second-, and third-year classes, respectively. Overall, the respondents were primarily single (84.6%), most had lived in urban settings (69.6%), and most did not have physician parents (82.5%) (Table 1). The overall mean (SD) age of respondents was 24.9 (2.3) years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents by preferred career choice

| DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS | FAMILY MEDICINE, N (%) (N = 79) | EMERGENCY MEDICINE, N (%) (N = 31) | SURGICAL SPECIALTIES, N (%) (N = 44) | MEDICAL SPECIALTIES, N (%) (N = 126) | TOTAL, N (%) (N = 280) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class year | |||||

| • First | 22 (27.8) | 11 (35.5) | 17 (38.6) | 38 (30.2) | 88 (31.4) |

| • Second | 27 (34.2) | 14 (45.2) | 18 (40.9) | 50 (39.7) | 109 (38.9) |

| • Third | 30 (38.0) | 6 (19.4) | 9 (20.5) | 38 (30.2) | 83 (29.6) |

| Sex* | |||||

| • Male | 23 (29.1) | 17 (54.8) | 35 (79.5) | 70 (55.6) | 145 (51.8) |

| • Female | 55 (69.6) | 14 (45.2) | 9 (20.5) | 56 (44.4) | 134 (47.9) |

| • Not recorded | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Age, y* | |||||

| • < 25 | 23 (29.1) | 18 (58.1) | 23 (52.3) | 73 (57.9) | 137 (48.9) |

| • ≥ 25 | 55 (69.6) | 13 (41.9) | 19 (43.2) | 47 (37.3) | 134 (47.9) |

| • Not recorded | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.5) | 6 (4.8) | 9 (3.2) |

| Race | |||||

| • White | 48 (67.6) | 23 (74.2) | 28 (63.6) | 71 (56.3) | 170 (60.7) |

| • Asian | 15 (19.0) | 5 (16.1) | 9 (20.5) | 32 (25.4) | 61 (21.8) |

| • South Asian | 8 (10.1) | 2 (6.5) | 5 (11.4) | 14 (11.1) | 29 (10.4) |

| • Aboriginal | 5 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 6 (2.1) |

| • Other | 3 (3.8) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (4.5) | 8 (6.3) | 14 (5.0) |

| Marital status | |||||

| • Single | 61 (77.2) | 26 (83.9) | 39 (88.6) | 111 (88.1) | 237 (84.6) |

| • Married or common law | 17 (21.5) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (11.4) | 14 (11.1) | 41 (14.6) |

| • Separated, divorced, or widowed | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) |

| Rural or urban origin* | |||||

| • Rural origin (< 25 000 population) | 37 (46.8) | 9 (29.0) | 8 (18.2) | 31 (24.6) | 85 (30.4) |

| • Urban origin (≥ 25 000 population) | 42 (53.2) | 22 (71.0) | 36 (81.8) | 95 (75.4) | 195 (69.6) |

| Physician parent | |||||

| • Yes | 16 (20.3) | 7 (22.6) | 9 (20.5) | 15 (11.9) | 47 (16.8) |

| • No | 63 (79.7) | 22 (71.0) | 35 (79.5) | 111 (88.1) | 231 (82.5) |

| • Not recorded | 0 (0) | 2 (6.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) |

P < .001.

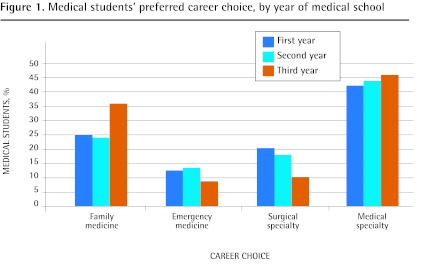

Career choice

Of the 280 respondents who selected from a list of 28 medical career options, 79 (28.2%) selected family medicine, 31 (11.1%) selected emergency medicine, 44 (15.7%) selected surgical specialties, and 126 (45.0%) selected medical specialties as their preferred career choice. There was a trend toward greater interest in family medicine as students progressed through medical school, especially from the preclinical to the clinical years (Figure 1). The preference for family medicine increased from 25.0% in the first-year class to 36.1% in the third-year class. In contrast, the preference for emergency medicine decreased from 12.5% to 7.2%, and for surgical specialties it decreased from 19.3% to 10.8%, from first to third year. Preference for the medical specialties remained fairly constant at 43.2% and 45.8% in the respective classes. Overall, 41.0% (55 of 134) of female and 15.9% (23 of 145) of male students preferred family medicine. Of the students who preferred family medicine, an overwhelming 69.6% were women. Of the students with rural backgrounds, 43.5% (37 of 85) chose family medicine as their preferred career choice, compared with only 21.5% (42 of 195) of students with urban backgrounds.

Figure 1.

Medical students’ preferred career choice, by year of medical school

Four factors were significantly associated with a preference for family medicine compared with the other specialties combined: emphasis on continuity of care (87.3% vs 45.3%, P < .001); length of residency (73.4% vs 25.9%, P < .001); influence of family, friends, or community (67.1% vs 50.2%, P = .011); and preference for working in a rural community (41.8% vs 10.9%, P < .001) (Table 2). In contrast, students who preferred specialty careers were more likely to be influenced by the opportunity to work on highly challenging cases (77.6% vs 53.2%, P < .001); the perceived intellectual content of the discipline (64.2% vs 48.1%, P = .014); an emphasis on procedural skills (67.7% vs 41.8%, P < .001); prestige (28.9% vs 10.1%, P < .001); income (58.2% vs 40.5%, P = .008); a preference for working in an urban centre (69.2% vs 35.4%, P < .001); the opportunity for research (30.8% vs 12.7%, P = .002); and mastering a small set of skills (54.7% vs 11.4%, P < .001).

Table 2.

Factors influencing medical students’ preferred career choice

| FACTORS | FAMILY MEDICINE, N (%) (N = 79) | EMERGENCY MEDICINE, N (%) (N = 31) | SURGICAL SPECIALTY, N (%) (N = 44) | MEDICAL SPECIALTY, N (%) (N = 126) | ALL SPECIALTIES COMBINED, N (%) (N = 201) | FAMILY MEDICINE VS ALL OTHERS, P VALUES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emphasis on continuity of care | 69 (87.3) | 8 (25.8) | 15 (34.1) | 68 (54.0) | 91 (45.3) | < .001 |

| Length of residency | 58 (73.4) | 8 (25.8) | 9 (20.5) | 35 (27.8) | 52 (25.9) | < .001 |

| Influence of family, friends, or community | 53 (67.1) | 11 (35.5) | 24 (54.5) | 66 (52.4) | 101 (50.2) | .011 |

| Positive experience with clinician or teacher of specialty | 52 (65.8) | 18 (58.1) | 38 (86.4) | 97 (77.0) | 153 (76.1) | .080 |

| Opportunity to work on acute medical problems | 49 (62.0) | 29 (93.5) | 37 (84.1) | 69 (54.8) | 135 (67.2) | .415 |

| Opportunity to work on highly challenging cases | 42 (53.2) | 23 (74.2) | 37 (84.1) | 96 (76.2) | 156 (77.6) | < .001 |

| Perceived intellectual content of discipline | 38 (48.1) | 14 (45.2) | 29 (65.9) | 86 (68.3) | 129 (64.2) | .014 |

| Preference for working in a rural community | 33 (41.8) | 8 (25.8) | 5 (11.4) | 9 (7.1) | 22 (10.9) | < .001 |

| Emphasis on procedural skills | 33 (41.8) | 24 (77.4) | 44 (100.0) | 68 (54.0) | 136 (67.7) | < .001 |

| Income | 32 (40.5) | 13 (41.9) | 26 (59.1) | 78 (61.9) | 117 (58.2) | .008 |

| Preference for working in an urban centre | 28 (35.4) | 17 (54.8) | 34 (77.3) | 88 (69.8) | 139 (69.2) | < .001 |

| Opportunity for research | 10 (12.7) | 2 (6.5) | 16 (36.4) | 44 (34.9) | 62 (30.8) | .002 |

| Master a small set of skills | 9 (11.4) | 7 (22.6) | 36 (81.8) | 67 (53.2) | 110 (54.7) | < .001 |

| Prestige | 8 (10.1) | 7 (22.6) | 18 (40.9) | 33 (26.2) | 58 (28.9) | < .001 |

| Specialty compatible with personality | 78 (98.7) | 31 (100.0) | 43 (97.7) | 122 (96.8) | 196 (97.5) | .525 |

| Opportunity to deal with a variety of medical problems | 75 (94.9) | 29 (93.5) | 37 (84.1) | 103 (81.7) | 169 (84.1) | .015 |

| Use a range of skills and knowledge in patient care | 73 (92.4) | 28 (90.3) | 37 (84.1) | 108 (85.7) | 173 (86.1) | .144 |

| Opportunity to teach | 51 (64.6) | 22 (71.0) | 33 (75.0) | 83 (65.9) | 138 (68.7) | .510 |

| Early exposure to discipline | 37 (46.8) | 14 (45.2) | 26 (59.1) | 57 (45.2) | 97 (48.3) | .830 |

| Overhead expenses | 37 (46.8) | 18 (58.1) | 23 (52.3) | 61 (48.4) | 102 (50.7) | .556 |

| Current debt load | 16 (20.3) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (9.1) | 16 (12.7) | 23 (11.4) | .057 |

There were some similarities and some differences between the specialties in terms of which factors were influential. Students interested in surgical specialties were more likely to be influenced by income potential and the prestige of the discipline, an emphasis on procedural skills, aspiring to work on highly challenging cases and acute medical problems, opportunities for research, positive experiences with clinicians or teachers in the specialty, and a preference for working in an urban centre. In comparison, those who preferred medical specialties were also more likely to be influenced by the perceived intellectual content of the discipline, income, a preference for working in an urban centre, and the desire for research opportunities. Students who preferred emergency medicine were more likely to desire to work on acute medical problems and placed a strong emphasis on procedural skills.

Rural versus urban background

Of all the respondents, 85 (30.4%) were classified as having rural backgrounds and 195 (69.6%) as having urban backgrounds. Students with rural backgrounds had lived on average 12.5 years in rural areas. Students from urban and rural backgrounds choosing family medicine had similar characteristics in terms of factors influencing career choice. The only difference between the 2 groups was preference for practice location. Students from urban backgrounds who chose family medicine were more likely to prefer urban practice locations, whereas students from rural backgrounds choosing family medicine preferred to practise in rural settings (P < .01).

Analysis within each category of student background revealed that the preference for family medicine versus other specialties was significantly influenced for students with urban backgrounds by family, friends, or community (P = .018); the opportunity to deal with a variety of medical problems (P = .045); and current debt load (P = .036). These factors did not influence those with rural backgrounds (Table 3). There were also differences between students with rural and urban backgrounds who preferred specialty careers. Whereas prestige (P = .010) and opportunities for research (P = .007) were significantly influential for students with urban backgrounds, income (P = .046) and positive experiences with clinicians or teachers of the particular specialty (P = .043) were more influential for students with rural backgrounds who selected specialty careers.

Table 3.

Factors influencing preferred career choice by urban versus rural background of students

| FACTORS |

URBAN BACKGROUND STUDENTS

|

RURAL BACKGROUND STUDENTS

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAMILY MEDICINE, N (%) (N = 42) | OTHER SPECIALTY, N (%) (N = 153) | P VALUE | FAMILY MEDICINE, N (%) (N = 37) | OTHER SPECIALTY, N (%) (N = 48) | P VALUE | |

| Emphasis on continuity of care | 37 (88.1) | 71 (46.4) | < .001 | 32 (86.5) | 20 (41.7) | < .001 |

| Length of residency | 30 (71.4) | 36 (23.5) | < .001 | 28 (75.7) | 16 (33.3) | < .001 |

| Influence of family, friends, or community | 30 (71.4) | 78 (51.0) | .018 | 23 (62.2) | 23 (47.9) | .191 |

| Positive experience with clinician or teacher of the specialty | 32 (76.2) | 117 (76.5) | .970 | 20 (54.1) | 36 (75.0) | .043 |

| Opportunity to work on highly challenging cases | 21 (50.0) | 116 (75.8) | .001 | 21 (56.8) | 40 (83.3) | .007 |

| Preference for working in a rural community | 8 (19.0) | 9 (5.9) | .007 | 25 (67.6) | 13 (27.1) | < .001 |

| Emphasis on procedural skills | 17 (40.5) | 103 (67.3) | .002 | 16 (43.2) | 33 (68.8) | .018 |

| Income | 20 (47.6) | 91 (59.5) | .169 | 12 (32.4) | 26 (54.2) | .046 |

| Preference for working in an urban centre | 22 (52.4) | 117 (76.5) | .002 | 6 (16.2) | 22 (45.8) | .004 |

| Opportunity for research | 4 (9.5) | 46 (30.1) | .007 | 6 (16.2) | 16 (33.3) | .074 |

| Master a small set of skills | 7 (16.7) | 85 (55.6) | < .001 | 2 (5.4) | 25 (52.1) | < .001 |

| Prestige | 5 (11.9) | 49 (32.0) | .010 | 3 (8.1) | 9 (18.8) | .162 |

| Opportunity to deal with a variety of medical problems | 40 (95.2) | 127 (83.0) | .045 | 35 (94.6) | 42 (87.5) | .267 |

| Current debt load | 10 (23.8) | 17 (11.1) | .036 | 6 (16.2) | 6 (12.5) | .626 |

DISCUSSION

Our study findings reveal that influences on the career choices of medical students are complex and multi-factorial, and that there are distinct differences in the factors that influence medical students who prefer family medicine compared with those who prefer specialty careers. This study also demonstrates differences in factors that influence medical career choice between students with urban and rural backgrounds. Students who prefer family medicine tend to place greater importance on continuity of care, desire a shorter residency period, and have a preference for working in rural communities. Interestingly, students with urban backgrounds are influenced to choose family medicine to a greater extent by family, friends, or the community than students with rural backgrounds are. In contrast, those who prefer specialty careers are influenced to a greater degree by prestige and income, procedural skills, research, and an urban orientation. These distinctive discipline-specific profiles of influential factors imply that medical students who prefer careers in family medicine possess different attributes to those who prefer specialty careers. This study reaffirms many known trends governing student career choice with more recent data and provides some insight into how decision factors are weighted differently for those who choose family medicine versus other specialties and between students with rural and urban backgrounds.

The relatively low interest in family medicine (28.2%) in our study is comparable to the 31.2% reported in a 2002 to 2004 survey of 8 Canadian medical schools8 and the 2010 CaRMS match results for the University of Alberta graduating medical students (only 29.5% selected family medicine during the first match).3 While the current emphasis on primary care reform in Alberta and Canada and the aging population are expected to increase the demand for family physicians, the declining interest in family medicine will likely create greater shortages. The pressure on medical schools and policy makers to implement innovative strategies to attract students into family practice is expected to intensify.

In our study, an overwhelming 69.6% of female students preferred family medicine as a career choice. The feminization of family medicine might continue to negatively affect the supply of family physicians, as female physicians are more likely to work part-time and to take time off to have families.17

Our study findings reveal that interest in family medicine appears to increase as students transition from the preclinical to the clinical years. This might be attributable to students having completed their family medicine clerkship rotation in third year. Increasing the number of family medicine experiences in the preclinical years, especially community-based experiences for urban students, could be beneficial in further increasing interest in family medicine. While our study was not designed to track those whose preferences switched into and out of family medicine during the course of medical school, given the observed differences in the influential factors for family medicine versus specialty career choices, we postulate that those who switch into family medicine might possess similar attributes to those who stay in family medicine throughout medical school. Ensuring that student exposure to family medicine focuses on dispelling myths and espousing the positive aspects of the discipline might be an effective method of raising student interest.

Many of the factors that influenced medical students’ choice of careers in this study have been described previously as reasons why fewer students are selecting family medicine.6,8,18,19 Specifically, prestige has been deemed an important influential factor in choosing a other specialty career. Increasing the prestige of family medicine is a difficult task given the hidden curriculum that pervades medical education, preconceived notions of the discipline, and the income differential between the other specialties and family practice. To address this issue, the Future of Medical Education in Canada project20 from the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada recommends an increased emphasis on generalism and addressing the hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education. The negative transmission of norms, values, and beliefs that is conveyed in formal educational content and informal social interactions against family medicine is a challenging issue for medical educators and policy makers to address. Increasing student exposure to family physicians in both the preclinical and clinical years might also go a long way to dispelling myths about low intellectual content of the field, the lack of opportunity to work on challenging cases, and an absence of procedural skills. Governments can assist medical schools by providing incentives and alternate payment models to encourage more family physicians to become involved in teaching and mentoring.

Our study reveals that a preference for family medicine is associated with a preference for working in a rural community. This implies that increasing admission of rural students into medical school would be expected to increase the supply of rural physicians. Interestingly, the study findings also indicate that students from urban backgrounds appear to be influenced to choose family medicine to a greater extent by family, friends, or the community than students from rural backgrounds are. This suggests that encouraging urban students to do extended family medicine clinical rotations in rural communities (such as the Integrated Clinical Clerkship program21) might encourage more urban students to consider careers in family medicine.

Limitations

Our study was limited by the cross-sectional nature of the survey, which provided a snapshot at a point in time and might not reflect changes over time. For logistic reasons, we were unable to survey the fourth-year class; therefore, the findings might not be generalizable to all undergraduate medical students. The questionnaire measured students’ “preferred” choice of medical career, and not “actual” choice. It is unknown whether students reported their unimpeded preferences or their realistic career choices. Determining the relative importance of the factors that influence career choice was also beyond the scope of this study. The questionnaire also might not have addressed the full breadth of factors that influence student interest in family medicine, although this was partially mitigated by including an “other” option for students to include alternative responses. The survey was conducted toward the end of each class year; carrying out the study at a different time during the year might have produced different results.

While much has been written about family physician shortages and the declining interest in family medicine, evaluation studies are very much needed to assess the effect of initiatives aimed at increasing interest in family medicine and the supply of family physicians. It would be informative to conduct a similar study in a medical school with a social accountability mandate and a predominantly community and rural focus. The criteria for student admission requirements and the influence of the philosophical and organizational milieu of medical education on the career choices of students require further investigation.

Conclusion

Medical students who prefer family medicine as a career choice appear to be influenced by a different set of factors than those who prefer specialty careers. A preference for family medicine is associated with placing a greater importance on continuity of care, a desire for a shorter residency, a preference for working in a rural community, and being influenced to a greater extent by family, friends, or the community. Female medical students, those 25 years of age and older, and those who have previously lived in rural locations also are more likely to prefer family medicine. While practice location differences exist between students from rural versus urban backgrounds, the preference for family medicine among students with urban backgrounds is more likely to be influenced by family, friends, or the community; the opportunity to deal with a variety of medical problems; and current debt load. Medical schools might consider introducing into the admissions process and the medical curriculum elements that would encourage family medicine as a career choice.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Research Office in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alberta for their assistance with this project.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

The purpose of this study was to examine factors that influence medical students’ career choice of family medicine versus specialty medicine and to analyze factors by rural versus urban background. Given that having a rural background is associated with increased interest in family medicine, an examination of factors that influence the career choices of students from rural backgrounds might provide insight into ways to increase the general appeal of family medicine.

Students from urban and rural backgrounds choosing family medicine were influenced by similar factors. Students from urban backgrounds who chose family medicine were more likely to prefer urban practice locations. Students with urban backgrounds were more likely to be influenced by family, friends, or community; the opportunity to deal with a variety of medical problems; and current debt load.

Interest in family medicine appeared to increase as students transitioned from the preclinical to the clinical years, possibly because students had completed their family medicine clerkship rotation in third year. Increasing the number of family medicine experiences in the preclinical years, especially community-based experiences for urban students, could be beneficial in further increasing interest in family medicine.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Cette étude avait pour but de cerner les facteurs qui font en sorte que les étudiants en médecine choisissent de faire carrière en médecine familiale plutôt que dans une autre spécialité et d’analyser ces facteurs en fonction de l’origine rurale versus urbaine des étudiants. Comme on observe une association entre le fait d’avoir un passé rural et un plus grand intérêt pour la médecine familiale, on pourrait mieux comprendre comment augmenter l’intérêt pour la médecine familiale si on examinait les facteurs qui influencent le choix de carrière des étudiants d’origine rurale.

Les étudiants d’origine urbaine ou rurale qui choisissent la médecine familiale étaient influencés par des facteurs semblables. Ceux d’origine urbaine qui choisissent la médecine familiale étaient plus susceptibles de préférer un lieu de pratique urbain. Ils étaient aussi plus susceptibles d’être influencés par leur famille, leurs amis ou leur communauté; par l’occasion de traiter une grande variété de problèmes médicaux; et par le niveau actuel de leur dette.

L’intérêt pour la médecine familiale semblait augmenter à mesure que les étudiants passaient des années précliniques aux années cliniques, possiblement parce que les étudiants avaient complété leurs stages de médecine familiale en troisième année. En multipliant les occasions de contact avec la médecine familiale durant les années précliniques, on pourrait augmenter l’intérêt pour la médecine familiale.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Drs Gill and McLeod initiated the study and were involved in developing the study design and survey questionnaire, interpreting study findings, and preparing the manuscript for submission. Ms Duerksen was involved in conducting the surveys, data analysis and interpretation, and preparing the manuscript for submission. Ms Szafran was responsible for overseeing the study, obtaining ethics approval, interpreting study findings, and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Chan BT. From perceived surplus to perceived shortage: what happened to Canada’s physician workforce in the 1990’s? Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2002. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?pc=PCC161. Accessed 2011 Jun 10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zink T, Center B, Finstad D, Boulger JG, Repesh LA, Westra R, et al. Efforts to graduate more primary care physicians and physicians who will practice in rural areas: examining outcomes from the University of Minnesota-Duluth and the Rural Physician Associate program. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):599–604. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2b537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Resident Matching Service . Reports and statistics, 2010. R-1 match reports. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2010. Available from: www.carms.ca/eng/operations_R1reports_10_e.shtml. Accessed 2011 Jan 2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blades DS, Ferguson G, Richardson HC, Redfern N. A study of junior doctors to investigate the factors that influence career decisions. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(455):483–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(6):502–12. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan J, Brown JB, Russell G. Choosing family medicine. What influences medical students? Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:1131–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bland CJ, Meurer LN, Maldonado G. Determinants of primary care specialty choice: a non-statistical meta-analysis of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70(7):620–41. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott I, Gowans M, Wright B, Brenneis F, Banner S, Boone J. Determinants of choosing a career in family medicine. CMAJ. 2011;183(1):E1–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassebaum DG, Szenas PL, Schuchert MK. Determinants of the generalist career intentions of 1995 graduating medical students. Acad Med. 1996;71(2):198–209. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199602000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright B, Scott I, Woloschuk W, Brenneis F, Bradley J. Career choice of new medical students at three Canadian universities: family medicine versus specialty medicine. CMAJ. 2004;170(13):1920–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson SR, Hoban JD, Mazmanian PE. Understanding primary care residency choices: a test of selected variables in the Bland-Meurer model. Acad Med. 2004;79(10 Suppl):S36–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200410001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefevre JH, Roupret M, Kerneis S, Karila L. Career choices of medical students: a national survey of 1780 students. Med Educ. 2010;44(6):603–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newton DA, Grayson MS, Whitley TW. What predicts medical student career choice? J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):200–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman K, Woloschuk W, Gowans M, Delva D, Brenneis F, Wright B, et al. The difference between medical students interested in rural family medicine versus urban family or specialty medicine. Can J Rural Med. 2008;13(2):73–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowman MA, Haynes RA, Rivo ML, Killian CD, Davis PH. Characteristics of medical students by level of interest in family practice. Fam Med. 1996;28(10):713–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fincher RM, Lewis LA, Jackson TW. Why students choose a primary care or nonprimary care career. The Specialty Choice Study Group. Am J Med. 1994;97(5):410–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarma S, Thind A, Chu MK. Do new cohorts of family physicians work less compared to their older predecessors? The evidence from Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(12):2049–58. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.047. Epub 2011 May 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosser WW. The decline of family medicine as a career choice. CMAJ. 2002;166(11):1419–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morra DJ, Regehr G, Ginsburg S. Medical students, money, and career selection: students’ perception of financial factors and remuneration in family medicine. Fam Med. 2009;41(2):105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada . The Future of Medical Education in Canada (FMEC): a collective vision for MD education. Ottawa, ON: Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada; 2010. Available from: www.afmc.ca/fmec/pdf/collective_vision.pdf. Accessed 2011 Jan 8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rural and Regional Health, Faculty of Medicine . Rural Integrated Community Clerkship program (Rural ICC) Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta; 2007. Available from: www.ruralandregionalhealth.med.ualberta.ca/ugme/clerkship.htm. Accessed 2011 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]