Abstract

Objective

To explore physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sexual and mood side effects of hormonal contraceptives, and to compare residents with practising doctors.

Design

A mixed-method study with faxed or e-mailed surveys and semistructured telephone interviews.

Setting

British Columbia.

Participants

A random sample of family doctors, all gynecologists, and all residents in family medicine and gynecology in the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia registry. A subsample was interviewed.

Main outcome measures

Estimates of rates of mood and sexual side effects of contraceptives in the practice population and how the physicians informed and advised patients about these side effects.

Results

There were 79 residents and 76 practising doctors who completed the questionnaires (response rates of 42.0% and 54.7% of eligible residents and physicians, respectively). The reference sources most physicians reported using gave the rates of sexual and mood side effects of hormonal contraceptives as less than 1%, and yet only 1 (0.6%) respondent estimated similar rates for mood side effects, and 12 (7.8%) for sexual effects among their patients. The most common answers were rates of 5% to 10%, with residents reporting similar rates to practising doctors. Practising doctors were more likely to ask about sexual and mood side effects than residents were (81.1% vs 24.1% and 86.3% vs 40.5%, respectively; P < .001). Practising doctors were also more likely to recommend switching to barrier methods (37.3% vs 16.5%; P = .003) or intrauterine devices (54.7% vs 38.0%; P = .038) than residents were and more likely to give more responses to the question about how they managed sexual and mood side effects (mean of 1.7 vs 1.1 responses, P = .001). In 14 of the 15 interviews, practising doctors discussed how they had learned about side effects mainly from their patients and how this had changed their practices.

Conclusion

Physicians’ perceived rates of mood and sexual side effects from hormonal contraception in the general population were higher than the rate of less than 1% quoted in the product monographs. Practising doctors reported that they learned about the type, frequency, and severity of side effects from their patients.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer les connaissances, attitudes et façons de faire des médecins en ce qui a trait aux effets indésirables des contraceptifs hormonaux, et comparer les résidents aux médecins en pratique.

Type d’étude

Études par méthodes mixtes, à l’aide d’enquêtes par télécopieur ou par courriel et d’entrevues téléphoniques.

Contexte

La Colombie-Britannique.

Participants

Un échantillon aléatoire de médecins de famille, tous les gynécologues et tous les résidents en médecine familiale et en gynécologie inscrits au registre du Collège des médecins et chirurgiens de la Colombie-Britannique.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Estimations des taux d’effets indésirables des contraceptifs sur l’humeur et l’activité sexuelle chez leurs clients, et types d’information et de conseils que les médecins donnent aux patients à propos de ces effets indésirables.

Résultats

Au total, 79 résidents et 76 médecins en pratique ont répondu au questionnaire (taux de réponse de 42,0 et 54,7 %, respectivement pour les résidents et les médecins). Les sources de références utilisées par la plupart des médecins donnaient des taux d’effets indésirables des contraceptifs hormonaux sur l’humeur et l’activité sexuelle inférieurs à 1 % et pourtant, seulement 1 des répondants (0,6 %) estimait des taux semblables pour les effets sur l’humeur de ses patients et 12 (7,8%), pour les effets sur l’activité sexuelle. Les réponses les plus fréquentes situaient les taux entre 5 et 10 %, les taux rapportés étant similaires pour les résidents et les médecins en pratique. Les médecins en pratique étaient plus susceptibles que les résidents de s’enquérir des effets indésirables sur l’humeur et l’activité sexuelle (81,1 vs 24,1 % et 86,3 vs 40,5 %, respectivement; P < ,001). Ces médecins étaient également plus susceptibles que les résidents de recommander de changer pour une méthode de barrière (37,3 vs 16,5 %; P = ,003) ou un stérilet (54,7 vs 38,0 %; P < ,038), et plus susceptibles de donner plus de réponses à la question portant sur la façon dont ils traitaient les effets sur l’activité sexuelle et sur l’humeur (moyenne de 1,7 vs 1,1 réponses, P = ,001). Dans 14 des 15 entrevues, les médecins en pratique ont mentionné que c’est surtout par l’intermédiaire de leurs patients qu’ils ont connu les effets indésirables et ils ont souligné comment cela avait changé leur pratique.

Conclusion

Les médecins croyaient que les taux d’effets indésirables des contraceptifs hormonaux sur l’humeur et l’activité sexuelle dans la population générale étaient plus élevés que le taux de 1 % mentionné dans les monographies des produits. Les médecins en pratique ont mentionné que ce sont leurs patients qui les ont informés du type, de la fréquence et de la gravité des effets indésirables.

Physicians can learn about drug side effects from a variety of sources. It is not unreasonable to hypothesize that residents receive most of their knowledge from lectures and research publications, while practising doctors supplement their knowledge with their patients’ experiences.

Side effects are concerning when they cause serious harm or discontinuation of medication. In the US National Survey of Family Growth, of 6724 reproductive-aged women who had ever used contraception, 29% indicated they had discontinued oral contraceptives (OCs) owing to dissatisfaction with the method.1 In a prospective study of 76 women in stable committed relationships, 1 year after starting OCs, only 38% continued with the original brand of OCs, 47% had discontinued the medication, and 14% had switched to another OC.2 Emotional and sexual side effects were the best predictors of discontinuation and switching, with emotional side effects, worsening of premenstrual syndrome, decreased frequency of sexual thoughts, and decreased psychosexual arousability categorizing 87% of cases. A study comparing side effects and continuation rates of 3 different hormonal contraceptives reported that “the analysis of adverse events revealed two crucial points for acceptability, compliance and continuation: poor cycle control and disturbance of sexual intercourse due to vaginal dryness and loss of desire.”3 In another study of 1086 German medical students, hormonal contraception was related to lower sexual functioning scores (ie, on the Female Sexual Functioning Index), especially desire and arousal.4

A 2006 review of 30 years of medical literature on the sexual effects of hormones (35 reports) stated, “Although sexual side effects have been noted in various subgroups of women using hormonal contraception, no consistent pattern of effect exists to suggest a hormonal or biological determinant.”5 A 2004 review of 30 original research papers published between 1959 and 1990 stated, “Overall, women experience positive effects, negative effects, as well as no effect on libido during OC use.”6 The Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (CPS), a commonly used drug reference book for doctors in Canada, quotes rates of less than 1% for mood and sexual side effects for hormonal contraceptives.7 A commonly used Web-based resource (UpToDate) does not mention mood or sexual side effects in its list of the adverse effects of hormonal contraception.8 A search of the literature revealed no reports dealing with this discrepancy in rates of sexual side effects or of physicians’ perceptions. There are some reports of similar problems with sexual side effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). For example, the 2011 CPS reports rates of 3% for decreased libido and 2% for impotence as the only sexual side effects of fluoxetine, and yet a review of 79 randomized controlled trials of SSRIs noted that the rates varied from 0% to 57.7% depending on whether patients were asked any specific questions about sexual side effects and which questions were asked.7,9 Randomized controlled trials are usually poorly equipped to assess side effects because they are focused on efficacy or effectiveness, have small samples (for rare events), and have short follow-up periods. Postmarketing observational studies usually report much higher rates of adverse events and side effects. This study aimed to explore physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sexual and mood side effects of hormonal contraceptives and to compare residents with practising doctors.

METHODS

This was a mixed-method study with a questionnaire survey of family doctors, gynecologists, and family practice and gynecology residents; semistructured interviews were undertaken with a subsample of participants. The questionnaires were faxed to every sixth family doctor in alphabetic listing in the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia (BC) registry and to every gynecologist in the same registry. The offices were telephoned by a research assistant to assess whether each doctor was eligible—that is, had a clinical practice in which he or she saw women for contraception needs and did not have an office policy of refusing all surveys. E-mails with a link to the online survey were sent to all family practice and gynecology residents at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, the sole medical school in BC. All residents were considered eligible. We used a modified Dillman tailored design method with pretesting and 3 faxes or e-mails, but with no incentive reward or introductory letter or postcard before the survey (owing to budgetary and time constraints).10 There were 15 questions that asked respondents to estimate the rates of mood and sexual side effects in their practice populations and asked how they informed and advised patients about these side effects. This survey was piloted on 10 physicians and revised appropriately. Only minor revisions were implemented following the pilot. To further examine the results of the survey, a physician, a medical student, and a counselor then interviewed a purposive subsample of 15 survey participants by telephone using semistructured interviews. We chose only practising doctors and second-year residents so they would have real experience with patients to discuss. We ensured that we had new and experienced doctors, those in urban, suburban, and rural practices, both male and female doctors, and both family doctors and gynecologists in our subsample. The initial interviews were recorded, transcribed, and e-mailed to the investigators, who discussed the emerging themes via e-mail. This information was used to explore some of the themes more thoroughly in subsequent interviews. After theme saturation was reached, the investigators met in person and a consensus was reached on the theme analysis.

The data from the surveys were entered into an SPSS database (PASW, version 18) and descriptive statistics were generated. Responses of residents were compared with those of practising doctors using χ2 statistics. Multivariate logistic regressions were used to adjust for the potential effect of sex and specialty. The study was approved by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia.

RESULTS

There were 79 residents and 76 practising doctors who completed the questionnaires (response rates of 42.0% and 54.7% of eligible residents and physicians, respectively). Of 542 faxed surveys, we found that the BC College registry was inaccurate for 17.3% (n = 94) of listings, 2.6% (n = 14) of possible participants were away, 18.5% (n = 100) were not eligible (eg, they saw only geriatric or oncology patients), and 36.3% (n = 197) had an office policy of not participating in any surveys. When we compared the respondents to the nonrespondents in terms of the information available from the BC College registry, we found that the nonrespondents were more likely to be male (P = .02), less likely to be white (P = .002), more likely to have urban-based practices (P = .002), and more likely to have been in practice for more than 15 years (P < .001).

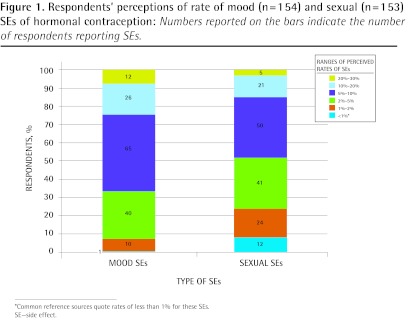

When asked to estimate what percentage of women complained of side effects, 1 (0.6%) respondent gave the rate of less than 1% for mood effects, and 12 (7.8%) gave this rate for sexual effects. The most common answers were rates of 5% to 10%, with residents providing similar estimates to practising doctors (Figure 1). When asked about the effect on discontinuation of OCs, residents perceived sexual side effects to be more important and practising doctors perceived mood side effects to be more important (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Respondents’ perceptions of rate of mood (n=154) and sexual (n=153) SEs of hormonal contraception: Numbers reported on the bars indicate the number of respondents reporting SEs.

*Common reference sources quote rates of less than 1% for these SEs.

SE—side effect.

Table 1.

Respondents’ perceptions of the effect of sexual and mood side effects on discontinuation of hormonal contraception

| SIDE EFFECTS |

NO. OF RESPONDENTS INDICATING SIDE EFFECTS WERE AMONG THE TOP 3 REASONS FOR DISCONTINUATION OF CONTRACEPTION

|

P VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRACTISING DOCTORS, N (%) (N = 76*) | RESIDENTS, N (%) (N = 79*) | ||

| Sexual side effects | 10 (17.5) | 57 (76.0) | .021 |

| Mood side effects | 36 (64.3) | 32 (43.8) | < .001 |

Responses for some questions are missing.

Practising doctors were more likely to report asking about sexual and mood side effects than residents were (81.1% vs 24.1% asked “at least sometimes” about sexual side effects, and 86.3% vs 40.5% asked about mood side effects; P < .001) (Table 2). These univariate differences were confirmed in multivariate logistic regression analysis that adjusted for sex and specialty. Practising doctors were more than 11 times more likely to ask about sexual side effects and almost 10 times more likely to ask about mood side effects than residents were. In addition, female respondents were more than twice as likely as their male counterparts to ask about mood side effects (results not shown). Practising doctors were also more likely to recommend switching to barrier methods (P = .003) and intrauterine devices (P = .038) than residents were (Table 2). In multivariate analysis, the difference was statistically significant for the barrier method (odds ratio 2.89; 95% CI 1.23 to 7.76; P = .015)—with practising doctors almost 3 times as likely as residents to recommend it—but not for the intrauterine device method.

Table 2.

Management of sexual and mood side effects of hormonal contraception

| PRACTICE | PRACTISING DOCTORS, N (%) (N = 76*) | RESIDENTS, N (%) (N = 79) | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asks about mood side effects (sometimes, usually, or always) | 63 (86.3) | 32 (40.5) | < .001 |

| Asks about sexual side effects (sometimes, usually, or always) | 60 (81.1) | 19 (24.1) | < .001 |

| Recommends changing to an intrauterine device | 41 (54.7) | 30 (38.0) | .038† |

| Recommends changing to a barrier method | 28 (37.3) | 13 (16.5) | .003 |

Responses for some questions are missing.

Not significant in multivariate model.

Practising doctors were more likely to give more responses to the question about what they recommended to women complaining about sexual and mood side effects than residents were, with a mean of 1.7 responses vs 1.1 responses (P = .001).

Of the 92 female respondents who had previously used hormonal contraception themselves, 19 (20.7%) reported that they had experienced mood side effects themselves and 29 (31.5%) reported sexual side effects.

Qualitative results

The 15 doctors interviewed included 2 second-year family practice residents, 1 practising obstetrician-gynecologist, 1 male family doctor, and 11 female family doctors. Seven doctors said they were in urban practices, 2 were in suburban practices, and 5 were in rural practices. They had been in practice for a total of 229 years, with a range of 0 to 45 years.

In 14 of the 15 interviews, the doctors discussed how they learned about the type, frequency, and severity of sexual and mood side effects mainly from their patients. Regarding the 10% to 15% rate of sexual side effects, doctors said the following:

I think I ... I learnt it from patients.

(71-year-old male family doctor)

[Y]ou get people complaining about it all the time and that’s inconsistent with what the drug companies will relay as the side effects .... So, if you listen to patients you’ll hear rates that are high enough that make you wonder what the true ... you know, what the real answer is.

(33-year-old female family doctor)

Eleven of the 15 doctors interviewed discussed how their practices had changed after they had observed these high rates of side effects in their patients:

Oh, definitely, I would say that when I first started practice I prescribed the pill without a lot of thought and without as long a discussion as I have now with people. So, yeah, my conversations have definitely changed over the years with people.

(33-year-old female family doctor)

I definitely listen to them more when they’re telling me they’re not taking this because of such-and-such, whereas before I might have just looked it up in the CPS and said, “Well, actually, that doesn’t happen.”

(52-year-old female family doctor)

When asked which side effects were most likely to cause women to discontinue hormonal contraception, 13 of the 15 doctors cited mood effects. The next most commonly given reason was irregular bleeding (10 of 15). Libido was reported as a less common cause of discontinuation; however, many doctors stressed the fact that it is particularly difficult to assess because patients are often reluctant to discuss sexual matters.

I would say mood would be number one that I’ve heard from the youth. “It makes me crazy, makes me crazy.” I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard that.

(36-year-old female family doctor)

I would say the emotional factors like libido and mood are the bigger players on having people not use the pill on an ongoing basis.

(33-year-old female family doctor)

You know, I think probably the mood and libido ones are more important … and I think that those are the times that women will decide to quit on their own without coming in to see me … whereas with the other, the physical ones, they’re more likely to come in and talk about it and, you know, maybe try another pill.

(Female family doctor with 30 years of experience)

Two doctors said that they thought the high rate of side effects they had seen in their practices was not representative of the general public: “[W]e don’t see the people who are happy. We don’t see the people who aren’t having troubles.” (42-year-old female family doctor)

When asked what resources they relied on, the most commonly used were the CPS (10 of 15), UpToDate (7 of 15), and drug company charts (6 of 15).

Five female physicians talked about learning from personal experience, others talked about learning from friends and colleagues, and only 1 mentioned lectures.

Actually, I went in to see my GP and said, “This stuff makes me want to kill my husband and children and that makes birth control sort of pointless.” I quit taking it. Which was one of the reasons that I started listening to the women a lot more when they started telling me about the side effects.

(52-year-old female family doctor)

When asked about how they query patients about side effects, only 6 of the 15 doctors reported asking specific questions. More often they would use open-ended general questions, or would not ask and would wait for patients to bring it up themselves.

People don’t report what you don’t ask them to. But the more you ask, the more you’ll find out about.

(Family doctor with 4 years of experience)

So I ask a very broad question, and, you know ... so they were just coming in for a renewal. I’ll say, “Any concerns with it? Any questions?” and then sometimes that comes up. Then they’ll say “Well, I’m just wondering. Ever since I started this, my libido doesn’t seem as good. Do you think it’s related, doc?”

(40-year-old female family doctor)

During the interviews, some doctors reflected on their practices and how they could be improved: “Actually, to ask about it is really a good idea. I think I have had a fear about planting that seed in their minds.” (Female family doctor with 30 years of experience)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report of how physicians learn about mood and sexual side effects of hormonal contraceptives. Practising doctors were more likely to ask about mood and sexual side effects and to recommend nonhormonal contraception for women complaining of these side effects. Most of the family doctors, gynecologists, and residents who answered the questionnaires or participated in the interviews in this study estimated the rates of mood and sexual side effects from hormonal contraceptives in their practices to be much higher than the rates quoted in the published resources they used for reference. Almost all of them attributed their knowledge of these side effects to what they observed in their patients. Practising doctors and residents had similar perceptions about rates of these side effects, but practising doctors were more likely to ask about side effects and more likely to recommend nonhormonal contraception to women complaining of these side effects.

The main limitation of this study was the low response rate. Unfortunately, there has been a trend toward lower response rates in studies of physicians’ knowledge and attitudes of various subjects.11 We know that in this study, our responders were more likely to be rural, female, white, and in practice less than 15 years compared with the nonrespondents. Knowing which doctors responded to the survey and which did not might help us interpret the results. It is likely that younger female physicians have more patients currently requesting contraception than older male physicians and so our sample might have a higher percentage of physicians with more current experience. Questionnaire studies like this one are limited by recall bias and self-reported data.

It has been shown that specific questions are more likely to elicit admissions of emotional and sexual side effects from contraceptives than open-ended questions are,12 and yet most doctors said they used open-ended questions. Many of the interviewees talked about how their practices changed as they began to integrate what they were hearing from their patients.

In a study of 661 family practice patients, only 69% of drug side effects were reported to their family doctors; physicians changed therapy in 76% of cases with reported side effects, and patients’ failure to report side effects was related to 21% of adverse drug reactions.13 Contraceptives are commonly used, so family doctors and gynecologists generally have extensive experience with them. With drugs that are used less often, doctors would likely rely to a greater extent on published reports and manufacturer’s information rather than patients.

Helping patients deal with sexual side effects of hormonal contraception is similar to the problem with SSRIs. It is always a difficult balancing act for family doctors to inform patients about side effects of medications without scaring them. As one of our interviewees said, “I have had a fear about planting that seed in their minds.”

Conclusion

Physicians’ estimated rates of mood and sexual side effects from hormonal contraception in women in their practices were higher than the less than 1% quoted in the product monographs. Practising doctors described how they learned about side effects from their patients and how they integrated their own experiences with evidence from published data. It is important for family physicians to help patients find contraception that does not interfere with their mood or sexual pleasure.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

In this study of physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sexual and mood side effects of hormonal contraceptives, practising doctors were more likely than residents to ask patients about mood and sexual side effects and to recommend nonhormonal contraception for women complaining of these side effects.

Most of the family doctors, gynecologists, and residents who answered the questionnaires or participated in the interviews in this study estimated the rates of mood and sexual side effects from hormonal contraceptives in their practices to be much higher than the rates quoted in the published resources they used for reference.

It is important for family physicians to help patients find contraception that does not interfere with their mood or sexual pleasure.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Dans cette étude qui traite des connaissances, attitudes et façons de faire des médecins en rapport avec les effets indésirables des contraceptifs hormonaux sur l’humeur et sur l’activité sexuelle, les médecins en pratique étaient plus susceptibles que les résidents de s’enquérir auprès de leurs patients de ces effets et de recommander aux femmes qui se plaignent de tels effets indésirables de recourir à des méthodes contraceptives non hormonales.

La plupart des médecins de famille, gynécologues et résidents qui ont répondu au questionnaire ou participé aux entrevues croyaient que les taux d’effets indésirables des contraceptifs hormonaux étaient beaucoup plus élevés que ceux mentionnés dans les publications qu’ils utilisaient comme référence.

Le médecin de famille se doit d’aider les patientes à trouver une méthode contraceptive qui n’interfère pas avec leur humeur ni avec le plaisir lié au sexe.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Moreau C, Cleland K, Trussell J. Contraceptive discontinuation attributed to method dissatisfaction in the United States. Contraception. 2007;76(4):267–72. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.06.008. Epub 2007 Aug 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders SA, Graham CA, Bass JL, Bancroft J. A prospective study of the effects of oral contraceptives on sexuality and well-being and their relationship to discontinuation. Contraception. 2001;64(1):51–8. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabatini R, Cagiano R. Comparison profiles of cycle control, side effects and sexual satisfaction of three hormonal contraceptives. Contraception. 2006;74(3):220–3. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.022. Epub 2006 Jun 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallwiener M, Wallwiener LM, Seeger H, Mueck AO, Zipfel S, Bitzer J, et al. Effects of sex hormones in oral contraceptives on the female sexual function score: a study in German female medical students. Contraception. 2010;82(2):155–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.022. Epub 2010 Feb 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaffir J. Hormonal contraception and sexual desire: a critical review. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32(4):305–14. doi: 10.1080/00926230600666311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis AR, Castaño PM. Oral contraceptives and libido in women. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2004;15:297–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compendium of pharmaceuticals and specialties: the Canadian drug reference for health professionals. 9th ed. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. UpToDate [website]. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, Inc; 2000. Available from: www.uptodate.com. Accessed 2011 Mar 2.

- 9.Haberfellner EM. A review of the assessment of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction used in randomized, controlled clinical trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2007;40(5):173–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet surveys: the tailored design method. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook JV, Dickinson HO, Eccles MP. Response rates in postal surveys of healthcare professionals between 1996 and 2005: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:160. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiebe ER, Trouton KJ, Dicus J. Motivation and experience of nulliparous women using intrauterine contraceptive devices. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32(4):335–8. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weingart SN, Gandhi TK, Seger AC, Seger DL, Borus J, Burdick E, et al. Patient-reported medication symptoms in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(2):234–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]