Abstract

Background

Biofilms are often antibiotic resistant, and it is unclear if prophylactic antibiotics can effectively prevent biofilm formation. Experiments were designed to test the ability of high (bactericidal) concentrations of ampicillin (AMP), vancomycin (VAN), and oxacillin (OXA) to prevent formation of suture-associated biofilms initiated with low (104) and high (107) numbers of Staphylococcus aureus.

Materials and methods

S. aureus biofilms were cultivated overnight on silk suture incubated in biofilm growth medium supplemented with bactericidal concentrations of AMP, VAN, or OXA. Standard microbiological methods were used to quantify total numbers of viable suture-associated S. aureus. Crystal violet staining followed by spectroscopy was used to quantify biofilm biomass, which includes bacterial cells plus matrix components. To observe the effects of antibiotics on the microscopic appearance of biofilm formation, biofilms were cultivated on glass slides, then stained with fluorescent dyes, and observed by confocal microscopy.

Results

In the presence of a relatively low inoculum (104) of S. aureus cells, bactericidal concentrations of AMP, VAN, or OXA were effective in preventing development of suture-associated biofilms. However, similar concentrations of these antibiotics were typically ineffective in preventing biofilm development on sutures inoculated with 107 S. aureus, a concentration relevant to contaminated skin. Confocal microscopy confirmed that bactericidal concentrations of AMP, VAN, or OXA inhibited, but did not prevent, development of S. aureus biofilms.

Conclusion

Bactericidal concentrations of AMP, VAN, or OXA inhibited formation of suture-associated biofilms initiated with low numbers (104), but not high numbers (107), of S. aureus cells.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Suture, Biofilm, Biomass, Confocal microscopy, Antibiotics, Ampicillin, Vancomycin, Oxacillin

1. Introduction

Microbial biofilms are involved in a wide variety of infectious processes, such as periodontitis, otitis media, ventilator- and cystic fibrosis–related pneumonias, endocarditis, biliary tract infections, prostatitis, osteomyelitis, burn wound infections, device-related infections, and wound infections [1–3]. Biofilm infections are especially troubling in clinical medicine because microbes residing within a biofilm are generally more antibiotic resistant than their planktonic (free-living) counterparts [1,4]. In addition to increased antibiotic resistance, biofilms exhibit increased resistance to ultraviolet damage, desiccation, and pH gradients (reviewed in [5]). Using Staphylococcus aureus suture-associated biofilms [6], we have reported that bacteria residing in the biofilm are antibiotic resistant, even though mechanically dispersed biofilm cells have susceptibilities comparable with planktonic bacteria [7]. Lewis [8,9] has described a small percentage of biofilm cells, termed “persister” cells, thought to be responsible for the antibiotic resistance of biofilms, and persister cells are currently the topic of a considerable research effort. Because the antimicrobial recalcitrance of biofilm infections is a daunting problem, we designed experiments to clarify the effect of prophylactic antibiotics on the development of S. aureus suture-associated biofilms.

Although prophylactic antibiotics are frequently given to prevent infections, little is known about the ability of antibiotics to actually prevent biofilm development (and there is some evidence that antibiotics can actually enhance biofilm development [10]). Unfortunately, there are no universally accepted methods for studying the ability of antibiotics to prevent biofilm formation. Bacterial antibiotic susceptibilities are assessed in clinical microbiology laboratories by incubating various concentrations of a drug with low numbers of rapidly growing bacteria. The resulting antibiotic concentration that results in bacterial killing is defined as the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC). If a drug was administered at a concentration resulting in a steady state MBC level in the patient’s blood (often difficult to obtain), one would expect that this drug should prevent susceptible bacteria from initiating a biofilm infection. We sought to test whether ampicillin (AMP), vancomycin (VAN), and oxacillin (OXA) at concentrations relevant to the MBC could prevent biofilm formation using two strains of S. aureus and then tested if these drug concentrations would inhibit development of suture-associated biofilms initiated with a low and high (but clinically relevant) inoculum of viable S. aureus.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antibiotics and S. aureus strains

S. aureus RN6390 and ATCC 25923 are wild type strains known to produce biofilms [6,7,11,12]. Bacterial inocula were washed cells from overnight cultures incubated at 35°C in tryptic soy broth, and bacterial concentrations were confirmed by standard microbiological methods. The antibacterial agents used in this study were all cell wall active agents and included AMP, VAN, and OXA (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc, St. Louis, MO). Using methodology compatible with CLSI guidelines [13], the MBCs of these antibiotics for planktonic cells of these two S. aureus strains have been published. The MBCs of AMP/VAN/OXA for strains RN6390 and ATCC 25923 are 0.5/2.0/0.5 μg/mL and 0.25/2.0/0.5 μg/mL, respectively [7]. MBC is defined as the minimum antibiotic concentration that results in 99.9% killing of the cells in the bacterial inoculum.

2.2. Effect of antibiotics on developing suture-associated S. aureus biofilms

Suture-associated biofilms were cultivated as described [6,7] with minor modifications. Briefly, each well of a 24-well microtiter plate contained a 1-cm segment of black braided 3–0 silk suture (Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, NJ) suspended in 1 mL of biofilm growth medium, namely 66% tryptic soy broth supplemented with 0.2% glucose [12] and additionally supplemented with varying concentrations of AMP, VAN, or OXA. Control wells contained no antibiotic. Each well was inoculated with 104 or 107 S. aureus and incubated overnight at 37°C with gentle rotation (50 rpm). These inocula were chosen as low and high inocula, based on the fact that high concentrations of bacteria on normal skin flora are 106–7/cm2 [14]. After overnight incubation of bacteria with suture, suture-associated biofilms were analyzed for numbers of viable bacteria and biofilm biomass as described below.

To assess the numbers of viable bacteria, each suture was gently rinsed, transferred to 2 mL of sterile phosphate buffered saline, sonicated at ~50 J at 100% amplitude for 5 s using a sonicator at 20 kHz (Sonics and Materials, Newtown, CT). Sonication had no noticeable effect on bacterial viability, and microscopy confirmed that sonicated bacteria were single-cell suspensions. Bacterial concentrations in sonicates were determined by standard microbiological methods, and the lower detection limit was 1.7 log10 colony forming units (CFUs) per suture. Biofilm biomass was measured with crystal violet as described [15] with minor modifications. Crystal violet is a basic dye that binds negatively charged surface molecules, including those on live and dead bacteria, as well as on matrix polysaccharides. Biofilm-laden sutures were rinsed with phosphate buffered saline, fixed in 99% methanol for 15 min, air dried, incubated 20 min with 0.5% crystal violet (Fisher Chemical, Pittsburgh, PA), washed, and then incubated 20 to 30 min in 33% acetic acid to release the crystal violet, with absorbance read at 590 nm. Statistical differences were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t-test. Bacterial numbers were converted to log10 before statistical analysis, and significance was set at P < 0.05.

2.2.1. Confocal microscopy

To facilitate microscopic observations, biofilms were cultivated overnight at 37°C on positively charged glass slides using biofilm growth medium inoculated with ~107/mL S. aureus and supplemented with either AMP (0.125 and 0.5 μg/mL), VAN (1 and 2 μg/mL), or OXA (0.125 and 0.5 μg/mL) or no drug. Adherent biofilms were gently rinsed with Hanks balanced salt solution, fixed for 10 min in cold methanol, and rehydrated in Hanks balanced salt solution. Fluorescent stains were purchased from Invitrogen, Eugene, OR. Samples were stained with a mixture of 10 μg/mL of the lectin wheat germ agglutinin (which binds the cell surface polysaccharide poly-N-acetylglucosamine in S. aureus cell walls [16]) conjugated to AlexaFluor 594 and 5 μg/mL of Hoechst 33342, a cell permeable nucleic acid stain. Hoescht dyes are very sensitive to the conformation and chromatic state of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and bind more readily to DNA than ribonucleic acid, and these dyes are thus considered a marker of genomic DNA. Stained samples were mounted in Vectashield Hardset (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), and images were acquired with a Cascade 1k EMCCD camera (Photo-metrics, Tucson, AZ) as wide field z-stacks using a 100×1.45 NA objective (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Z-stacks were taken at 0.2 μm intervals, and images are shown as best focus projections (Metamorph, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of bacterial inoculum on biofilm development in the presence of bactericidal concentrations of AMP, VAN, and OXA

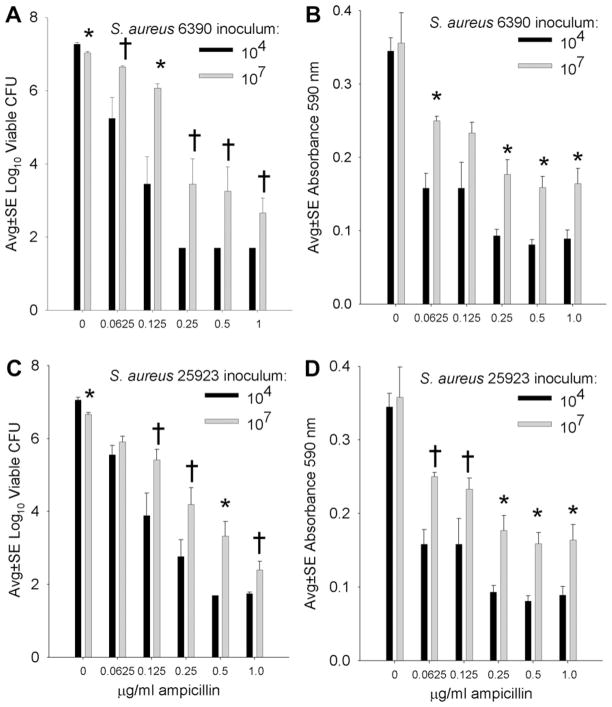

Figure 1 presents the effect of varying concentrations of AMP (including bactericidal concentrations 0.25 and 0.5 μg/mL) on the development of S. aureus biofilms on silk suture incubated overnight with low (104) and high (107) numbers of S. aureus. With an inoculum of 104 S. aureus, bactericidal concentrations of AMP effectively inhibited biofilm formation and the viable CFU recovered from suture were at the lower limits of assay detection (Fig. 1A and C). Consistent with this result, low biomass was detected in corresponding samples (Fig. 1B and D). When a high bacterial inoculum (107) was used, high concentrations of AMP (≥MBC) did not prevent biofilm development, as assayed by viable CFU and biofilm biomass (Fig. 1). Direct comparison of the ability of AMP to inhibit biofilm growth in the presence of low or high bacterial inocula typically revealed that AMP was significantly more effective in inhibiting biofilms initiated with the low (104) compared with the high (107) bacterial inoculum (Fig. 1). Similar observations were made with each of the two S. aureus strains used in this study.

Fig. 1.

Comparative effect of low (104) and high (107) inocula of S. aureus RN6390 (A, B) and ATCC 25923 (C, D) incubated overnight on silk suture in the presence of varying concentrations of AMP, where the MBC for S. aureus 6390 was 0.25 μg/mL and S. aureus 25923 was 0.5 μg/mL. A and C present the numbers of viable S. aureus recovered from suture-associated biofilms, and B and D present the biofilm biomass measured as absorbance of crystal violet. * and †indicate a difference compared with the corresponding lower inoculum at P <0.01 and 0.05, respectively. Each bar represents 10 to12 assays.

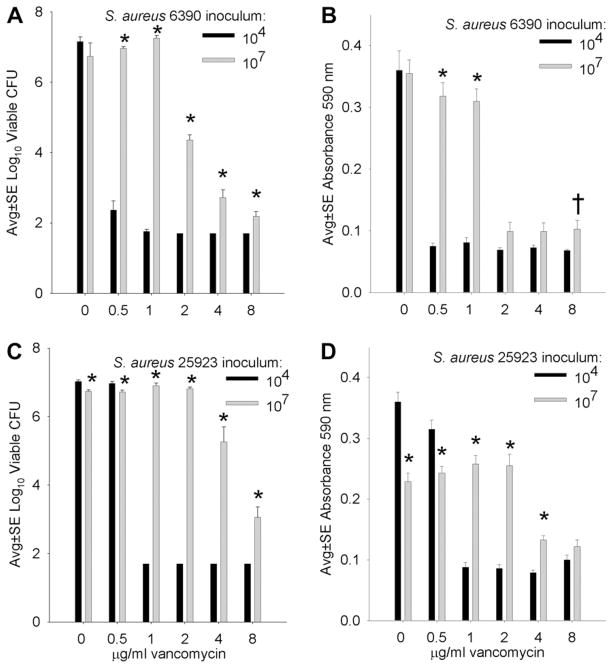

Compared with results obtained with AMP (Fig. 1), similar data were obtained from biofilms cultivated in high bactericidal (≥2 μg/mL) concentrations of VAN, that is, bactericidal concentrations of VAN were effective in limiting formation of biofilms initiated with lower (104) but not higher (107) S. aureus inocula (Fig. 2). Again, direct comparisons of results between the two inocula often revealed significantly more robust biofilm formation with the higher, compared with lower, S. aureus inoculum (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparative effect of low (104) and high (107) inocula of S. aureus RN6390 (A, B) and ATCC 25923 (C, D) incubated overnight on silk suture in the presence of varying concentrations of VAN, where the MBC for both S. aureus strains was 2 μg/mL. A and C present the numbers of viable S. aureus recovered from suture-associated biofilms, and B and D present the biofilm biomass measured as absorbance of crystal violet. * and †indicate a difference compared with the corresponding lower inoculum at P <0.01 and 0.05, respectively. Each bar represents eight assays.

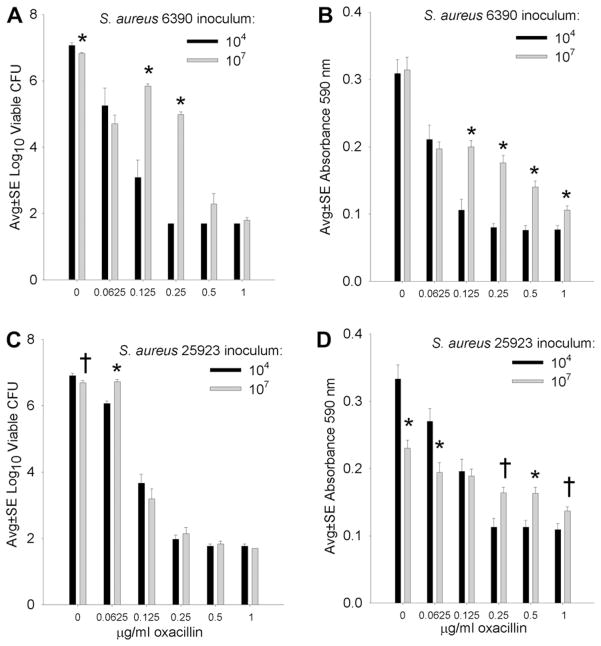

Figure 3 presents the effect of varying concentrations of OXA (including the bactericidal concentration 0.5 μg/mL) on the development of S. aureus biofilms on silk suture incubated overnight after inoculation with low (104) or high (107) numbers of S. aureus (Fig. 3). Although S. aureus ATCC 25923 appeared more susceptible to OXA than the RN6390 strain, bactericidal concentrations (0.5 and 1 μg/mL) effectively limited biofilm development in the presence of both low (104) and high (107) S. aureus inocula. Again, a general observation was that biofilm development depended on the antibiotic concentration and the size of the bacterial inoculum (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparative effect of low (104) and high (107) inocula of S. aureus RN6390 (A, B) and ATCC 25923 (C, D) incubated overnight on silk suture in the presence of varying concentrations of OXA, where the MBC for both S. aureus strains was 0.5 μg/mL. A and C present the numbers of viable S. aureus recovered from suture-associated biofilms, and B and D present the biofilm biomass measured as absorbance of crystal violet. * and †indicate a difference compared with the corresponding lower inoculum at P <0.01 and 0.05, respectively. Each bar represents 12 assays.

3.2. Effect of bactericidal concentrations of AMP, VAN, and OXA on microscopic appearance of biofilm development

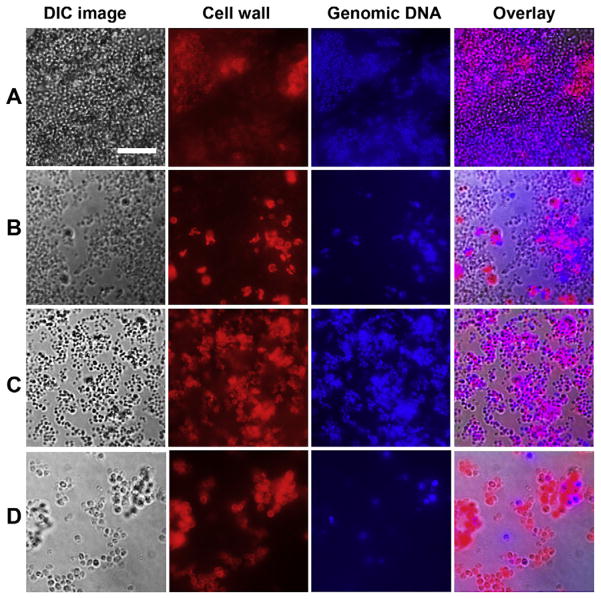

To facilitate microscopic observation of biofilm development in the presence of antibiotics, S. aureus biofilms were cultivated on glass slides, then observed by confocal microscopy using a method whereby intact S. aureus cell walls fluoresced red and intact genomic DNA fluoresced blue (Fig. 4). Antibiotic concentrations included 0.125 and 0.5 μg/mL AMP, 1 and 2 μg/ mL VAN, and 0.125 and 0.5 μg/mL OXA, and similar observations were made with both concentrations of a given antibiotic. In control biofilms cultivated without antibiotic, robust biofilms formed that had much heterogeneity and were up to 19 μm in depth. The general appearance of control biofilms could be described as hills and valleys of normally sized (~0.6 μm diameter) coccal cells (Fig. 4, row A). Although some biofilm formation was evident in the presence of all antibiotic concentrations (Fig. 4, rows B–D), cellular elements were noticeably sparser in the presence of AMP and OXA (Fig. 4, rows B and D). Biofilms cultivated in the presence of VAN (Fig. 4, row C) were not as dense as control biofilms, although some areas had robust growth comparable with controls. Biofilms cultivated in the presence of AMP (row B) and OXA (row D) had S. aureus cells that were often three to four times larger than normal cells, indicating that these cell wall active agents interfered with normal cell division. With each of the three antibiotics, cell wall and genomic DNA staining were more variable compared with S. aureus cells in control biofilms, suggesting antibiotic-induced alterations in the integrity of bacterial cell walls and genomic DNA. A general observation from these biofilms cultivated on glass slides using a high (107/mL CFU) S. aureus inoculum was that bactericidal concentrations of AMP, VAN, and OXA inhibited, but did not prevent, biofilm development (Fig. 4). This observation was consistent with the effect of antibiotics on development of suture-associated biofilms, where bactericidal concentrations of antibiotics were ineffective in preventing the development of biofilms initiated with a high (107), yet clinically relevant, number of viable S. aureus (Figs. 1–3).

Fig. 4.

S. aureus (rows A and D, strain 25923; rows B and C, strain 6390) biofilms cultivated overnight on glass slides in the presence of no drug (A), 0.125 μg/mL AMP (B), 2 μg/mL VAN (C), and 0.5 μg/mL OXA (D). Each row contains a light microscopy image using differential interference contrast microscopy, followed by corresponding best focus images from confocal z-stacks that localized cell wall material (red) and genomic DNA (blue) followed by an overlay of these three images. Note robust biofilm only in row A, relatively large S. aureus cells in the presence of AMP and OXA, and the variability in cell wall and genomic DNA staining in antibiotic-treated samples. All images are at the same magnification; scale bar is 10 μm.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to clarify the effect of bacterial inoculum on suture-associated biofilms incubated with high antibiotic concentrations. Studying the effects of antibiotics on biofilm formation can be problematic because of the lack of a standardized methodology to measure antibiotic resistance in biofilm-associated bacteria. Further, there is no standard methodology to measure the effect of various interventions, including antibiotics on biofilm development. We sought to test the effect of antibiotics on the development of S. aureus biofilms. Because MBC data are only available for planktonic bacteria, and not for biofilm-associated bacteria, we tested the effect of a range of antibiotic concentrations on the development of S. aureus biofilms initiated with low and high numbers of viable bacteria. To assess the effects of antibiotics on biofilm development, we used standard micro-biological methods to test bacterial viability, the crystal violet method to measure biofilm biomass, and confocal imaging to observe the effects of antibiotics on biofilm development at the cellular level. These techniques allowed us to correlate structural findings with objective measurements of bacterial viability and biofilm biomass.

We found differences in the effects of antibiotics on biofilm development, and these differences were dependent on the size of the bacterial inoculum used to initiate the biofilm. When the concentration of antibiotic was at or near the MBC, an S. aureus inoculum of 104 CFU/mL resulted in biofilm viability at the lower limit of assay detection and biomass measurements decreased correspondingly. When the larger inoculum (107 CFU/mL) was used, biofilm viability decreased with increasing antibiotic concentrations but remained detectable at antibiotic concentrations at or above the MBC. Because the MBC is strictly defined as the antibiotic concentration that kills 99.9% of inoculated bacteria, one might expect detectable viability in biofilms initiated with an inoculum of 107 bacteria. Also, as expected, biomass measurements paralleled the results on bacterial viability, and biofilms with higher numbers of bacteria had greater biomass.

Confocal microscopy revealed that biofilm structural formation was most robust in control specimens (Fig. 4 row A) and that antibiotic-treated specimens had some degree of biofilm formation (Fig. 4, rows B–D), consistent with the recovery of lower numbers of viable bacteria in antibiotic-treated samples (Figs. 1–3). Additional structural differences were appreciated in these overnight biofilm specimens, depending on the antibiotic used. S. aureus biofilms cultivated in the presence of the penicillins, AMP and OXA, revealed scattered, enlarged, bacterial forms (Fig. 4, rows B and C). Using planktonic cells of S. aureus, electron microscopic studies documented that, before penicillin-mediated cell death, disorganization of peptidoglycan cross wall architecture leads to the inhibition of cell division and the formation of “pseudomulticellular” staphylococci [17]. It is possible that the large bacterial forms seen by confocal microscopy after cultivation of S. aureus biofilms with AMP or OXA represented the pseudomulticellular forms previously noted on electron microscopic images [17]. Pseudomulticellular S. aureus may result from binding between antibiotic molecules and trans-peptidase enzymes also known as penicillin-binding proteins located on the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane and within the splitting-system, a structure found in bacterial cross walls important for daughter cell separation during cell division [17]. In contrast to the β-lactam antibiotics, AMP and OXA, large bacterial forms were not a feature of S. aureus biofilms grown in the presence of VAN, a glycopeptide antibiotic (Fig. 4, row C). Free floating in the periplasm, VAN does not appear to directly affect cell division [17,18]. VAN binds to the peptidoglycan dipeptide, D-alanyl-D-alanine thereby blocking transglycosylase and transpeptidase (penicillin-binding protein) activity and chain synthesis [18]. Although both VAN and the penicillins disrupt cell wall homeostasis, each of these agents has a unique mechanism of action consistent with the differences in the resulting microscopic appearance of antibiotic-treated S. aureus biofilms viewed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4).

In the clinical setting, tissue concentrations of antibiotics may vary considerably from the concentration that is achievable in the serum or in the laboratory setting. The data reported in this study attempt to answer the basic question of whether antibiotics can prevent biofilm formation and whether the original inoculum has an impact on the effect of antibiotics on biofilm formation. These results cannot be directly extrapolated to the clinical setting. Similarly, the suture material chosen for these investigation was selected because it provides an excellent substrate for biofilm formation and has yielded very reproducible results. Other suture types used in varying clinical situations may yield different results.

This study represents a novel investigation into the possibility that antibiotic exposure at the time of initial bacterial inoculation might alter or prevent biofilm development. Each antibiotic used in this study inhibited but did not prevent biofilm formation, particularly when larger bacterial inocula were used. In the clinical setting, prophylactic antibiotics are unlikely to reach tissue concentrations similar to those used in this investigation. Assuming that these in vitro findings are relevant to the clinical situation, these data suggest that prophylactic antibiotics may inhibit, but not prevent, infectious biofilm formation, particularly in the presence of a relatively high, yet clinically relevant, bacterial inoculum.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM095553 (to CW) and in part by funds from the Department of Surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (to DH). Parts of this work were performed in the Institute of Technology Characterization Facility, University of Minnesota, which receives partial support from NSF through the MRSEC (gs3) program.

Footnotes

Presented at the Seventh Annual Academic Surgical Congress (Association for Academic Surgery), Las Vegas, NV, February 14–16, 2012.

References

- 1.Fux CA, Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Stoodley P. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:34. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cogan NG, Gunn JS, Wozniak DJ. Biofilms and infectious diseases: biology to mathematics and back again. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;322:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cos P, Tote K, Horemans T, et al. Biofilms: an extra hurdle for effective antimicrobial therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2279. doi: 10.2174/138161210791792868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monds RD, O’Toole GA. The developmental model of microbial biofilms: ten years of a paradigm up for review. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:73. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry-Stanley MJ, Hess DJ, Barnes AMT, Dunny GM, Wells CL. Bacterial contamination of surgical suture resembles a biofilm. Surg Infect. 2010;11:433. doi: 10.1089/sur.2010.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells CL, Henry-Stanley MJ, Barnes AMT, Dunny GM, Hess DJ. Relationship between antibiotic susceptibility and ultrastructure of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms on surgical suture. Surg Infect. 2011;12:297. doi: 10.1089/sur.2010.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis K. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:48. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis K. Persister cells. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:357. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman LR, D’Argenio DA, MacCoss MJ, Zhang Z, Jones RA, Miller SI. Aminoglycoside antibiotics induce bacterial biofilm formation. Nature. 2005;436:1171. doi: 10.1038/nature03912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fux CA, Wilson S, Stoodley P. Detachment characteristics and oxacillin resistance of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm emboli in an in vitro catheter infection model. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4486. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4486-4491.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanks RMQ, Donegan NP, Graber ML, et al. Heparin stimulates Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4596. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4596-4606.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CLSI Guidelines. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Approved Standard M100-S16. 16. CLSI; Wayne, PA, USA: 2006. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis CP. Normal flora. In: Baron S, editor. Medical microbiology. 4. Galveston: The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. p. 114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peeters E, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Comparison of multiple methods for quantification of microbial biofilms grown in microtiter plates. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;72:157. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maira-Litran T, Kropec A, Abeygunawardana C, et al. Immunochemical properties of the staphylococcal poly-N-acetylglucosamine surface polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4433. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4433-4440.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giesbrecht P, Kersten T, Maidhof H, Wecke J. Staphylococcal cell wall: morphogenesis and fatal variations in the presence of penicillin. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1371. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1371-1414.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Collins JJ. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nature Rev/Microbiology. 2010;8:423. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]