Abstract

The race-specific peptide elicitor AVR9 of the fungus Cladosporium fulvum induces a hypersensitive response only in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants carrying the complementary resistance gene Cf-9 (MoneyMaker-Cf9). A binding site for AVR9 is present on the plasma membranes of both resistant and susceptible tomato genotypes. We used mutant AVR9 peptides to determine the relationship between elicitor activity of these peptides and their affinity to the binding site in the membranes of tomato. Mutant AVR9 peptides were purified from tobacco (Nicotiana clevelandii) inoculated with recombinant potato virus X expressing the corresponding avirulence gene Avr9. In addition, several AVR9 peptides were synthesized chemically. Physicochemical techniques revealed that the peptides were correctly folded. Most mutant AVR9 peptides purified from potato virus X::Avr9-infected tobacco contain a single N-acetylglucosamine. These glycosylated AVR9 peptides showed a lower affinity to the binding site than the nonglycosylated AVR9 peptides, whereas their necrosis-inducing activity was hardly changed. For both the nonglycosylated and the glycosylated mutant AVR9 peptides, a positive correlation between their affinity to the membrane-localized binding site and their necrosis-inducing activity in MoneyMaker-Cf9 tomato was found. The perception of AVR9 in resistant and susceptible plants is discussed.

The outcome of many plant-pathogen relationships is governed by the presence or absence of matching pathogen avirulence (Avr) genes and plant-resistance (R) genes. When both the Avr and the matching R gene are expressed, a resistance response is induced. This phenomenon has been described as the gene-for-gene interaction (Flor, 1971). To date, a variety of Avr and R genes have been cloned and sequenced. The cloned Avr genes include more than 30 bacterial genes (for review, see Dangl, 1994; Leach and White, 1996), as well as viral and fungal genes (van Kan et al., 1991; Joosten et al., 1994; Rohe et al., 1995; Taraporewala and Culver, 1996; Padgett et al., 1997). Although several R genes have been cloned (Staskawicz et al., 1995), only a few that have Avr genes with matching specificity have been isolated (presented in Table I). It has been proposed that race-specific resistance results from the direct interaction of the products of an Avr gene and the corresponding R gene (Gabriel and Rolfe, 1990; Staskawicz et al., 1995). At present, evidence supporting this hypothesis is available only for the interaction between one bacterial Avr-gene product, AvrPto, and its complementary R-gene product, Pto (Tang et al., 1996; Scofield et al., 1996).

Table I.

Matching pairs of cloned R and Avr genes

| R Gene | Isolated from | Matching Avr Gene | Pathogen | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pto | Tomato | AvrPto | Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato | Martin et al. (1993) |

| RPS2 | Arabidopsis | AvrRpt2 | P. syringae pv tomato | Bent et al. (1994) |

| RPM1/RPS3 | Arabidopsis | AvrRpm1/AvrB | P. syringae pv maculicola | Grant et al. (1995) |

| Bisgrove et al. (1994) | ||||

| Cf-4 | Tomato | Avr4 | C. fulvum | Thomas et al. (1997) |

| Cf-9 | Tomato | Avr9 | C. fulvum | Jones et al. (1994) |

The interaction between tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) and the fungal pathogen Cladosporium fulvum complies with the gene-for-gene relationship. The tomato R genes Cf-2, Cf-4, Cf-5, and Cf-9 confer resistance to races of C. fulvum that express the corresponding Avr genes Avr2, Avr4, Avr5, and Avr9, respectively. The sequences of these R genes predict that they encode extracytoplasmic glycoproteins containing imperfect, 24-amino acid LRRs, motifs involved in protein-protein interactions (Kobe and Deisenhofer, 1995; Jones and Jones, 1996). The Avr4 and Avr9 genes have been cloned and sequenced (van Kan et al., 1991; van den Ackerveken et al., 1992; Joosten et al., 1994). The Avr4 gene encodes a preproprotein of 135 amino acid residues. The mature AVR4 peptide elicitor, for which almost no structure-activity data are available, consists of 86 amino acids, of which 8 are Cys, potentially forming 4 disulfide bonds (Joosten et al., 1997). The Avr9 gene encodes a 63-amino acid preproprotein containing one potential glycosylation site (residues N-03, S-04, and S-05 of the mature peptide) (van den Ackerveken et al., 1993). The AVR9 elicitor predominantly present in C. fulvum-infected tomato plants contains 28 amino acids and is not glycosylated (van den Ackerveken et al., 1993). A variety of larger AVR9 peptides are found in in vitro-grown cultures of transgenic C. fulvum overexpressing AVR9 (van den Ackerveken et al., 1993). Peptides of 28 to 34 amino acids have been identified, some of which are N-glycosylated, containing two GlcNAc's and a variable number of Man residues (P.J.G.M. de Wit and P. Vossen, unpublished data). The global fold of the AVR9 peptide has been determined by 2D-NMR spectroscopy (Vervoort et al., 1997). The AVR9 elicitor contains a β-sheet of three antiparallel strands and three disulfide bonds arranged in a cystine knot (Isaacs, 1995). The AVR9 elicitor is structurally related to small inhibitor peptides, such as protease inhibitors and ion-channel blockers (Vervoort et al., 1997).

A high-affinity binding site for AVR9 is present on plasma membranes of tomato genotypes that are either susceptible (MM-Cf0) or resistant (MM-Cf9) to AVR9-producing races of C. fulvum. A binding site is also present on membranes of other solanaceous plant species (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). The affinity of AVR9 to the binding site is similar for tomato and for other solanaceous plants with a Kd of 70 pm. The binding site in tomato is specific for the AVR9 peptide, since it does not bind AVR4 or other small Cys-rich peptides (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). It is unknown whether the high-affinity binding site is required for the AVR9-induced HR in MM-Cf9 tomato plants.

Recently, we have assigned amino acid residues of the AVR9 peptide, which are important for necrosis-inducing activity in MM-Cf9 tomato plants, by independently substituting each amino acid of AVR9 for Ala or another amino acid (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997). Elicitor activity of mutant AVR9 peptides was studied by expressing the corresponding mutated Avr9 gene in MM-Cf9 tomato plants using the PVX expression system (Chapman et al., 1992). The severity of necrosis induced by each PVX::Avr9 construct was subsequently assessed. We identified amino acid substitutions resulting in AVR9 mutants with higher, similar, or lower necrosis-inducing activity compared with the wild-type AVR9 peptide. Some AVR9 mutants showed no necrosis-inducing activity (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997). The objective of this study was to determine whether the necrosis-inducing activity of mutant AVR9 peptides correlates with their affinity to the tomato-binding site, suggesting a key role for the binding site in the induction of AVR9/CF-9-dependent resistance. A selection of AVR9 peptides was either purified from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco (Nicotiana clevelandii), or was synthesized chemically (E. Mahé, P. Vossen, H.W. van den Hooven, D. Le-Nguyen, J.J.M. Vervoort, and P.J.G.M. de Wit, unpublished data). The affinity of the mutant AVR9 peptides to the tomato binding site was determined and their necrosis-inducing activity in MM-Cf9 tomato was analyzed. We show a positive correlation between binding affinity and necrosis-inducing activity for most of the mutant AVR9 peptides. The role of the AVR9 binding site in Cf-9-induced resistance is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of Mutant AVR9 Peptides from PVX::Avr9-Infected Plants

The necrosis-inducing activity of mutant AVR9 peptides has been assessed previously by determining systemic necrosis induced by mutant PVX::Avr9 derivatives on MM-Cf9 tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) plants (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997). Mutant AVR9 peptides with higher (R08K and R18K), lower (S05A, F10A, F10S, H22L, and H28L), or no detectable (F21A and L24S) necrosis-inducing activity in the PVX-based assay were selected for further studies. Several of these mutant peptides, including S05A, R08K, F10S, R18K, H22L, L24S, H28L, and wild-type AVR9, were isolated from the AF of tobacco (Nicotiana clevelandii L.) inoculated with the corresponding PVX::Avr9 derivative. Mutant PVX::Avr9 constructs were made as described previously (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997).

Plasmid DNA was isolated and infectious 5′ capped mRNA was obtained using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE in vitro transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Leaves of 4-week-old tobacco plants were inoculated with the infectious mRNA as described previously (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997). Ten to 14 days after inoculation, leaves showing systemic mosaic symptoms were harvested for preparation of sap containing the infectious virus. For the purification of each mutant AVR9 peptide, at least 25 5-week-old tobacco plants were inoculated with sap containing the corresponding infectious virus. After 2 weeks, leaves that showed mosaic symptoms were selected and the AF was isolated (de Wit and Spikman, 1982). Mutant AVR9 peptides were purified as described previously (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997). The peptides were further characterized by LpH-PAGE, ES-MS, 1D-NMR spectroscopy, and CD spectroscopy.

In addition, AVR9 was isolated from the AF of transgenic tomato plants expressing the Avr9 gene under transcriptional control of the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, as described by Honée et al. (1995). Transgenic tomato plants expressing the Avr9 gene were kindly provided by M. Stuiver (MOGEN International NV, Leiden, The Netherlands). AVR9 was also isolated from the AF of C. fulvum-infected tomato plants, as described by van den Ackerveken et al. (1993).

Chemical Synthesis of AVR9 Peptides

Wild-type AVR9 and mutant peptides with higher (R08K), lower (F10A), and no (F21A) necrosis-inducing activity were chemically synthesized and folded (E. Mahé, P. Vossen, H.W. van den Hooven, D. Le-Nguyen, J.J.M. Vervoort, and P.J.G.M. de Wit, unpublished data). These peptides were purified on reversed-phase HPLC and analyzed by LpH-PAGE, ES-MS, and 2D-NMR spectroscopy.

Quantification of AVR9 Peptides

LpH-PAGE (Reisfeld et al., 1962) was performed to estimate the concentrations of the mutant AVR9 peptides. Different dilutions of the peptides were analyzed on a gel, and the intensity of both the Coomassie blue- and silver-stained AVR9 peptide bands was visually compared with the intensity of 1 μg of the wild-type AVR9 isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato plants, which was used as a standard. The concentration of the standard AVR9 was determined by A280 measurements using a molar extinction coefficient of 1640, as determined by the GCG sequence-analysis software package (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI).

NMR and CD Spectroscopy

1D-NMR spectra were recorded as described by Vervoort et al. (1997). CD spectra were recorded on a Spectropolarimeter (model DP J-600, Jasco, Easton, MD) connected to an IBM personal computer. Quartz cells with a 0.1-cm path length were used in the wavelength region from 190 to 260 nm (scan speed, 50 nm min−1; time constant, 1 s; bandwidth, 1 nm). Ten scans were averaged and smoothed.

The global fold and disulfide bridging of the synthetic AVR9 peptides (R08K, F10A, and F21A) were investigated by 2D-NMR spectroscopy at 600 MHz and were compared with synthetic wild-type AVR9 (E. Mahé, P. Vossen, H.W. van den Hooven, D. Le-Nguyen, J.J.M. Vervoort, and P.J.G.M. de Wit, unpublished data ). 3JNH-Hα coupling constants were determined by inverse Fourier transformation (Szyperski et al., 1992).

MS

ES-MS of all peptides was performed on a Finnigan MAT SSQ-710 machine (Austin, TX). Ten micrograms of purified AVR9 was dissolved in a mixture of methanol:water (80:20, v/v) plus 1% acetic acid and infused at a flow rate of 1 μL min−1. For electrical contact a sheath flow of 1 μL min−1 was used. N2 was used as drying gas at a temperature of 250°C. The mass spectra were collected in the profile mode, scanning at 1 s per scan. For each sample 64 scans were averaged. The molecular mass was calculated with the deconvolution program BIOMASS (Finnegan MAT, Austin, TX).

Membrane Isolations and Competition Binding

Microsomal membranes were isolated from leaves of tomato MM-Cf0 and MM-Cf9 plants as described previously (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). Competition binding assays with mutant AVR9 peptides were performed as described previously (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996), using a volume of 100 μL per reaction. Ten micrograms of membrane protein was resuspended in 80 μL of binding buffer (10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, and 0.1% BSA) and 10 μL of 10−10 m 125I-AVR9 and 10 μL of competitor peptide were added. Binding was performed by incubation at 37°C for 3 h under gentle shaking in a water bath. Glass-fiber filters (GF/F, Whatman) were soaked for 1 to 2 h in 0.5% polyethylenimine, transferred to a Millipore filtration manifold, and washed with 5 mL of water and 2 mL of binding buffer. Filtration of the samples was carried out at 104 Pa and filters were subsequently washed with 12 mL of binding buffer. The filters were transferred to scintillation vials and 3 mL of LumaSafe Plus (Lumac B.V., Groningen, The Netherlands) was added. Radioactivity was counted in a scintillation counter (model LS-6000 TA, Beckman). Kd values were calculated according to the method of Hulme and Birdsall (1992) using the equation: RL = Rt × K × L/(1 + K × L + KA × A), where RL is the bound ligand, Rt is the receptor concentration, K is the affinity constant (1/Kd) of 125I-AVR9, L is the 125I-AVR9 concentration, KA is the affinity constant of the competitor peptide, and A is the competitor peptide concentration.

Necrosis-Inducing Activity Assays

Peptides were tested further for necrosis-inducing activity by injection assays. A dilution series of the peptides was prepared and 20 μL of each concentration was injected near the main vein of a MM-Cf9 leaflet (de Wit et al., 1985). Control injections were performed in MM-Cf0 leaflets.

RESULTS

Mutant AVR9 Peptides Are Folded Correctly

To test whether the various mutant AVR9 peptides were folded correctly, they were analyzed by NMR and CD spectroscopy. Mutant AVR9 peptides isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco were obtained in microgram amounts per plant, resulting in a total amount of 25 to 50 μg of peptide. 1D-NMR spectroscopy of these mutant AVR9 peptides showed characteristics also observed in the spectra of wild-type AVR9, indicating that there were no major structural differences between the peptides. CD spectra of the peptides showed typical β-sheet characteristics (data not shown).

In addition, milligram quantities of wild-type AVR9 and the mutant AVR9 peptides R08K, F10A, and F21A were chemically synthesized and the peptides were folded (E. Mahé, P. Vossen, H.W. van den Hooven, D. Le-Nguyen, J.J.M. Vervoort, and P.J.G.M. de Wit, unpublished data). The conformations of the synthetic AVR9 peptides were studied by 2D-NMR spectroscopy. The synthetic 28-residue AVR9 peptide adopted a similar conformation as the corresponding residues of the 33-residue AVR9 peptide isolated from in vitro-grown cultures of C. fulvum (H.W. van den Hooven and J.J.M. Vervoort, unpublished data). The mutants R08K and F10A displayed almost identical chemical shifts, 3JNH-Hα coupling, and nuclear Overhauser enhancement data as the synthetic wild-type AVR9, apart from the ring-current shift effects for the F10A mutant (E. Mahé, P. Vossen, H.W. van den Hooven, D. Le-Nguyen, J.J.M. Vervoort, and P.J.G.M. de Wit, unpublished data). Thus, the amino acid substitutions of R08K and F10A had little or no effect on the spatial structure and disulfide bonding of the molecule. F21A was the only mutant in which significant differences in chemical shifts and 3JNH-Hα coupling constants were observed for residues D-20, A-21, H-22, and K-23. However, the conformation of the F21A peptide outside of the mutated area showed no significant changes compared with the wild-type AVR9 (E. Mahé, P. Vossen, H.W. van den Hooven, D. Le-Nguyen, J.J.M. Vervoort, and P.J.G.M. de Wit, unpublished data). The chemical shift indices (Wishart et al., 1992), which are indicative of secondary structure in proteins, were virtually identical for all four synthetic AVR9 peptides. Thus, the global fold of the synthetic AVR9 peptides is almost identical, and the differences in necrosis-inducing activity reflect only the local effect of the amino acid substitution.

AVR9 Produced by Tomato and Tobacco Plants Is Glycosylated

The molecular masses of all mutant AVR9 peptides were determined by ES-MS (Table II). The wild-type AVR9 peptide elicitor, isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato leaves, and the synthetic wild-type AVR9 had experimental molecular masses of 3188.5 and 3189.1 D, respectively. This is in good agreement with the theoretical molecular mass of 3189.6 D for the 28-residue peptide containing three disulfide bonds. The chemically synthesized and folded peptides all showed the expected mass, indicating the presence of three disulfide bonds. However, the wild-type AVR9 peptide isolated and purified from PVX::Avr9-infected N. clevelandii showed an experimental mass of 3391.1 D, which is about 202 kD higher than expected. AVR9 has one potential glycosylation site (N-03, S-04, S-05), and the observed mass difference suggests that the peptide contains one additional N-acetyl-hexosamine residue.

Table II.

Results of ES-MS analysis of wild-type and mutant AVR9 peptides

| Peptide | Theoretical Massa | Major Peakb | Difference between Major Peak and Theoretical Massc | Second Peakd | Difference between Second Peak and Theoretical Mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | |||||

| AVR9 (WT)e | 3189.6 | 3188.5 ± 1.4 | 1.1 | ||

| AVR9 (SY)f | 3189.6 | 3189.1 ± 0.1 | 0.5 | ||

| AVR9 (NC)g | 3189.6 | 3391.1 ± 0.7 | 201.5 | ||

| AVR9 (LE)h | 3189.6 | 3390.5 ± 1.7i | 200.9 | 3189.8 ± 0.5i | 0.2 |

| S05A (NC) | 3173.6 | 3171.5 ± 0.3 | 2.1 | ||

| R08K (SY) | 3161.6 | 3160.6 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | ||

| R08K (NC) | 3161.6 | 3364.2 ± 0.1 | 202.6 | 3161.2j | 0.4 |

| F10A (SY) | 3113.5 | 3113.0 ± 0.5 | 0.5 | ||

| F10S (NC) | 3129.5 | 3332.3 ± 0.6 | 202.8 | 3129.3 ± 0.5k | 0.2 |

| R18K (NC) | 3161.6 | 3364.5 ± 0.1 | 202.9 | 3160.6 | 1.0 |

| F21A (SY) | 3113.5 | 3112.6 ± 0.3 | 0.9 | ||

| H22L (NC) | 3165.6 | 3369.6 ± 0.4 | 204.0 | 3165.3 | 0.3 |

| L24S (NC) | 3163.5 | 3367.4 ± 0.4 | 203.9 | ||

| H28L (NC) | 3165.6 | 3368.3 ± 0.6 | 202.7 | 3164.8 | 0.8 |

The molecular mass of the peptide containing three disulfide bonds was calculated.

Mass corresponding to the main peak in the spectrum.

An additional mass of 202 kD can represent the presence of one GlcNAc residue.

Mass corresponding to a second peak detected in some of the spectra. The peak height was generally less than 5% of the main peak.

WT, Wild-type AVR9, isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato.

SY, Chemically synthesized peptide.

NC, Peptides isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco.

LE, AVR9 isolated from transgenic tomato.

The two peaks showed similar heights.

Very small additional peaks of 3678 and 3686 D were observed, indicating attachment of larger molecules.

The height of this peak is about one-half that of the height of the main peak.

The S05A peptide has a mutation in this glycosylation site and showed a calculated molecular mass of 3171.5 D, which was close to the expected molecular mass of the nonglycosylated peptide with three disulfide bonds (3173.6 D). Except for the S05A mutant, all other mutant AVR9 peptides purified from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco showed a molecular mass 200.9 to 204.0 kD higher than the expected mass (Table II). Thus, the observed mass difference between the experimental and theoretical masses of the AVR9 peptides isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco is indeed likely to be caused by glycosylation. Because the glycosylation site in AVR9 predicts N-glycosylation, most probably a GlcNAc (Vliegenthart and Montreuil, 1995) is attached to the Asn (N-03) of these mutant peptides. When the effect of the glycosylation is taken into account, the experimental masses of all mutant AVR9 peptides isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco are consistent with their theoretical masses, confirming the altered amino acid sequence and the presence of three disulfide bridges. Most of the glycosylated AVR9 peptides also show one additional smaller peak in the mass spectrum, representing the nonglycosylated form of the peptide (<5% of the primary peak). Only for F10S was the peak height of the glycosylated peptide about twice the height of that of the nonglycosylated peptide (Table II).

To determine whether tomato can also glycosylate AVR9, we performed ES-MS experiments on wild-type AVR9 isolated from tomato plants transgenic for the Avr9 gene (G. Honée, unpublished results). The mass spectrum of this AVR9 showed two peaks with comparable intensities, representing the nonglycosylated peptide (3189.8 D) and AVR9 with an additional GlcNAc residue (3390.5 D). This shows that both glycosylated and nonglycosylated AVR9 peptides can be produced in plants.

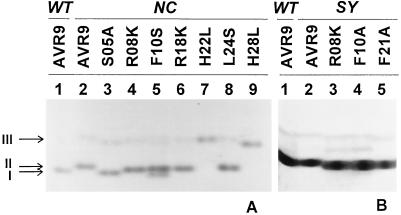

As shown in Figure 1, the glycosylated and nonglycosylated AVR9 peptides had different mobilities on native LpH-PAGE. The nonglycosylated wild-type AVR9 isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato (Fig. 1, arrow I) migrated slightly faster than the glycosylated wild-type AVR9 isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco (Fig. 1, arrow II). The migration patterns of the nonglycosylated S05A and the nonglycosylated AVR9 were the same. The other mutant AVR9 peptides isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco had the same mobility as the glycosylated wild-type AVR9. The two bands of the F10S mutant peptide represent both glycosylated and nonglycosylated forms. The H22L and H28L mutant peptides were less basic and migrated more slowly on the native LpH-PAGE. Figure 1B shows the results of native LpH-PAGE of the synthetic wild-type and mutant R08K, F10A, and F21A peptides. All synthetic AVR9 peptides migrated at the expected position, identical to the control (nonglycosylated) AVR9 isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato. In addition to the major band observed for all of the peptides, minor, slower-migrating bands were observed (Fig. 1, arrow III). These additional bands, observed for all AVR9 peptides in native LpH-PAGE, were not caused by differences in glycosylation, since they also occurred in the lanes containing chemically synthesized AVR9 peptides. These bands could represent slight alterations in the charge of the peptides, possibly resulting from deamination of Gln into Glu.

Figure 1.

A, Native LpH-PAGE of wild-type AVR9 isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato (WT) and wild-type and mutant AVR9 peptides from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco (NC). Approximately 1 μg was loaded per lane. B, LpH-PAGE of wild-type (WT) and chemically synthesized AVR9 peptides (SY). Approximately 2 μg was loaded per lane.

Mutant AVR9 Peptides Show Different Necrosis-Inducing Activities

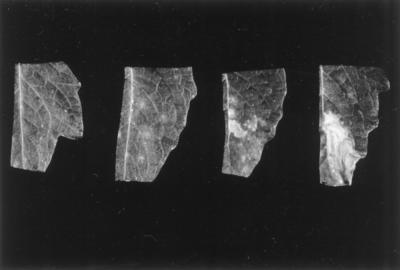

The necrosis-inducing activity of the various AVR9 peptides was tested by injecting 20 μL of the peptides with varying concentrations into leaflets of MM-Cf9 tomato plants. The observed necrosis was divided into four classes, as presented in Figure 2, varying from no necrosis to spreading necrosis. Table III shows a summary of the results of the necrosis-inducing activities of the mutant peptides. The wild-type AVR9 peptide isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato showed necrosis at concentrations of 0.3 μm and higher (Table III). The glycosylated wild-type AVR9 peptide isolated from the PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco showed similar necrosis-inducing activity as the nonglycosylated wild-type AVR9. The glycosylated and nonglycosylated R08K showed similar necrosis-inducing activities. This indicates that glycosylation does not affect the necrosis-inducing activity. The necrosis-inducing activity of the chemically synthesized wild-type AVR9 peptide was similar compared with the necrosis-inducing activity of wild-type AVR9 from C. fulvum-infected tomato. This was consistent with the 2D-NMR data, showing that the synthetic peptides are correctly folded. The necrosis-inducing activities of the two R08K mutants (synthetic and isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco) and of the R18K mutant (isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco) were stronger than that of wild-type AVR9. At 0.1 μm, these mutants induced necrosis, whereas wild-type AVR9 only induced chlorosis at this concentration (Table III). The necrosis-inducing activities of S05A, isolated from the PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco, and of the synthetic F10A mutant were slightly reduced; necrosis was induced at 1 μm and higher (Table III). Mutants F10S, H22L, and H28L, isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco, induced necrosis only at 3 μm and higher. The L24S isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco and the synthetic F21A did not show necrosis at the injected concentrations, but chlorosis was observed at 30 and 100 μm for the L24S and F21A mutants, respectively.

Figure 2.

Representation of four classes of AVR9-induced necrosis in MM-Cf9 leaflets as presented in Table III. Tomato (MM-Cf9) leaflets were injected with 20 μL of AVR9 isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato leaves. From left to right, concentrations of 0.03 μm (no necrosis), 0.1 μm (chlorosis), 0.3 μm (necrosis), and 10 μm (spreading necrosis).

Table III.

Necrosis observed upon injection of MM-Cf9 leaflets with wild-type and mutant AVR9 peptides of different concentrations

| Mutant | Necrosis

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 μm | 0.1 μm | 0.3 μm | 1 μm | 3 μm | 10 μm | 30 μm | 100 μm | |

| AVR9 (NC) | − | ± | + | + | ++ | ++ | NT | NT |

| AVR9 (WT) | − | ± | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| AVR9 (SY) | − | − | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| S05A (NC) | NT | − | − | + | + | NT | NT | NT |

| R08K (NC) | − | + | + | ++ | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| R08K (SY) | − | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| F10A (SY) | − | − | ± | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| F10S (NC) | NT | NT | − | ± | + | ++ | NT | NT |

| R18K (NC) | − | + | + | + | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| F21A (SY) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ± |

| H22L (NC) | NT | NT | − | ± | + | ++ | NT | NT |

| L24S (NC) | NT | NT | − | − | − | − | ± | NT |

| H28L (NC) | NT | NT | − | − | + | ++ | NT | NT |

Peptide designations are as in Table II. Examples of leaves showing no necrosis (−), chlorosis (±), necrosis (+), and spreading necrosis (++) are presented in Figure 2. The highest concentration tested (100 μm for all synthetic peptides and wild-type AVR9 and 1 to 10 μm for all other peptides) was also tested in MM-Cf0 leaflets. No necrosis or chlorosis was observed in MM-Cf0 for any of the peptides. NT, Not tested.

There was a clear correlation between the necrosis-inducing activity exhibited by a peptide injected in MM-Cf9 tomato leaflets and the systemic necrosis induced by the corresponding PVX::Avr9 derivative in MM-Cf9 plants described previously (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997). Fast and severe necrosis in the PVX-based assay corresponds to strong necrosis-inducing activity of the isolated peptide. Similarly, slow or little necrosis in the PVX-based assay corresponds to low necrosis-inducing activity of the isolated peptide. No necrosis induced by the PVX::Avr9 derivative concurs with no necrosis-inducing activity of the isolated peptide. Thus, the initial selection of peptides based on the PVX::Avr9-infected MM-Cf9 provides a reliable indication of the necrosis-inducing activity of the isolated AVR9 peptides (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997).

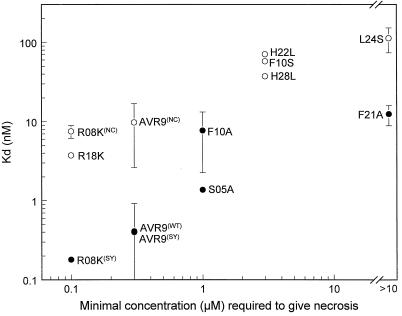

Mutant AVR9 Peptides Show Different Binding Affinities

To investigate a possible correlation between the necrosis-inducing activity of the various AVR9 peptides in MM-Cf9 plants and their affinity to the AVR9-binding site in tomato membranes, the Kd values of the peptides were determined by competition binding assays (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). The Kd values of the nonglycosylated peptides are summarized in Table IV. Figure 3 shows a scattergram in which the Kd values of the different AVR9 peptides are plotted against their necrosis-inducing activity. No accurate quantitative assay for the elicitor activity of AVR9 peptides was available and, therefore, the minimal concentration of a mutant AVR9 peptide required to induce necrosis (Table III) was used to indicate its activity. The binding affinity of most of the nonglycosylated AVR9 peptides correlated positively with their necrosis-inducing activity. The synthetic R08K mutant showed higher necrosis-inducing activity than wild-type AVR9 and also had a higher affinity to the binding site. Nonglycosylated mutants with low (S05A and F10A) and no detectable (F21A) necrosis-inducing activity had slightly lower (S05A) or much lower (F10A and F21A) affinities to the binding site. Nonbinding AVR9 mutants were not observed. Carboxy peptidase inhibitor and ω-conotoxin, two cystine-knotted peptides structurally homologous to AVR9, were included as the nonbinding controls (Sevilla et al., 1993; Chang et al., 1994; Vervoort et al., 1997). These did not compete for AVR9 binding, even at concentrations as high as 10 μm.

Table IV.

Affinities of mutant AVR9 peptides as determined by competition-binding analyses

| Peptide | Kd | n |

|---|---|---|

| nm | ||

| Nonglycosylated | ||

| AVR9 (WT) | 0.41 | 16 |

| AVR9 (SY) | 0.40 | 2 |

| S05A (NC)a | 1.37 | 1 |

| RO8K (SY) | 0.18 | 2 |

| F10A (SY) | 7.72 | 3 |

| F21A (SY) | 12.5 | 5 |

| CPIb | No comp. (>10,000) | 1 |

| CTX-GVIAb | No comp. (>10,000) | 1 |

| Glycosylated | ||

| AVR9 (NC) | 9.76 | 3 |

| R08K (NC) | 7.55 | 3 |

| F10S (NC)c | 57.7 | 2 |

| R18K (NC) | 3.74 | 2 |

| H22L (NC) | 70.8 | 2 |

| L24S (NC)d | 127 | 2 |

| L24S (NC)d | 98.1 | 2 |

| H28L (NC)e | 37.4 | 1 |

AVR9 (WT) indicates wild-type AVR9 isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato, (SY) indicates synthetic AVR9 peptides, and (NC) designates peptides isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco. n is the number of experiments. No comp., No competition of 125I-AVR9.

For S05A (NC) only one experiment could be performed because of the limited quantity of this peptide available.

Carboxy peptidase inhibitor (CPI) and ω-conotoxin GVIA (CTX-GVIA) are two peptides with structural homology to AVR9 (Isaacs, 1995).

Mixture of glycosylated and nonglycosylated peptides.

Results of two independent isolations from tobacco.

For H28L (NC) only one experiment could be performed because of the limited quantity of this peptide available.

Figure 3.

Scattergram showing the correlation between Kd values (Table IV) and necrosis-inducing activity of AVR9 peptides. The necrosis-inducing activity is represented as the minimal concentration required to induce necrotic lesions in MM-Cf9 tomato leaflets (Table III). Nonglycosylated peptides are represented by • and include all chemically synthesized peptides, AVR9 (WT) isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato, and the nonglycosylation mutant S05A isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco. The glycosylated peptides are represented by ○ and are all isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco. WT, SY, and NC are the same as in the legend to Figure 2. These designations are shown in the graph only for wild-type AVR9 and R08K, since these peptides were derived from different sources.

Table IV shows the Kd values of the glycosylated AVR9 peptides isolated from PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco. A positive correlation between binding affinity and necrosis-inducing activity was also observed for the glycosylated peptides. Comparison of both glycosylated R08K and R18K mutants with the glycosylated wild-type AVR9 showed a higher affinity of both mutant peptides and an increased necrosis-inducing activity. The glycosylated mutant peptides F10S, H22L, and H28L showed a lower affinity than the glycosylated wild-type AVR9 and a lower necrosis-inducing activity. The lowest affinity was observed for the inactive L24S mutant. The affinities of the glycosylated peptides were approximately 10- to 50-fold lower than the affinities of the nonglycosylated peptides.

All competition binding assays were performed using membranes of the tomato genotypes MM-Cf0 and MM-Cf9. The same differences in affinity were observed with membranes of MM-Cf0 plants as with the membranes of MM-Cf9 plants, indicating that the high-affinity binding sites in resistant and susceptible plants have identical binding properties. Also, in competition binding experiments to tobacco membranes (cv Petit Havana), which also have a high-affinity binding site for AVR9, the chemically synthesized AVR9 peptides showed values similar to those obtained for tomato membranes (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

Correlation between Necrosis-Inducing Activity and Binding Affinity of AVR9 Peptides

A high-affinity binding site for AVR9 is present in microsomal membrane fractions of solanaceous plant species (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). Our working hypothesis predicted that the high-affinity binding site for AVR9 is required for Cf-9-dependent HR. We used mutant AVR9 peptides to investigate a possible correlation between the affinity of these peptides to the binding site and their necrosis-inducing activity. Mutant AVR9 peptides were produced by expression of PVX::Avr9 derivatives in tobacco plants and by chemical synthesis. The mutant AVR9 peptides seemed to be correctly folded and, therefore, their necrosis-inducing activities and binding affinities are expected to reflect only the local effect of the amino acid substitution. AVR9 peptides produced by expression of PVX::Avr9 in tobacco are mostly glycosylated and contain one GlcNAc residue, whereas the AVR9 peptide isolated from C. fulvum-infected tomato is not glycosylated. Figure 3 shows that there is a positive correlation between necrosis-inducing activity of AVR9 peptides in MM-Cf9 plants and their affinity to the binding site for either the nonglycosylated or the glycosylated peptides. This suggests that the high-affinity binding site in MM-Cf9 may be required for Cf-9-dependent resistance.

In MM-Cf0 tomato plants, which also have a high-affinity binding site for AVR9, necrosis is not induced, suggesting that in MM-Cf9 at least one additional factor is involved in initiating the signal cascade that results in HR. This factor most probably is the CF-9 protein. Although there is a positive correlation between binding affinity and necrosis-inducing activity for most AVR9 peptides, the concentration of an AVR9 peptide required for the induction of necrosis is significantly higher than its Kd value. This might be attributable to the fact that the assay for HR is relatively insensitive. The assay for reactive oxygen species in leaves of MM-Cf9 is at least a 5-fold more sensitive, whereas the assay for generation of reactive oxygen species in Cf-9-transgenic tobacco cell cultures is even 100- to 500-fold more sensitive (C.F. de Jong, unpublished results). Although we found a positive correlation between binding affinity and necrosis-inducing activity for most AVR9 peptides, this did not hold for all peptides. The glycosylated and the nonglycosylated AVR9 peptides have similar necrosis-inducing activities, whereas their binding affinities are significantly different. Also, the F21A and L24S mutants showed no necrosis-inducing activity, but still showed low affinity to the binding site (discussed below).

The Kd value described here (0.41 ± 0.51 nm) is based on competition binding assays. This value is higher than the previously reported Kd value of 0.07 nm, which was based on saturation experiments (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). The latter is considered more accurate because it is determined by accurately quantified 125I-AVR9, whereas the Kd value calculated in competition assays is determined by less-accurately quantified, unlabeled AVR9.

Glycosylation of AVR9

In this study we have shown that glycosylation of AVR9 can occur in plants. AVR9 peptides with various degrees of glycosylation have also been found in culture filtrates of transgenic C. fulvum strains that overexpress the Avr9 gene (P.J.G.M. de Wit and P. Vossen, unpublished data). Thus, AVR9 can be glycosylated by different organisms. Usually, N-glycosylation in eukaryotes involves the attachment of two GlcNAcs and a number of Man residues (Vliegenthart and Montreuil, 1995). We have shown by MS that most of the wild-type AVR9 peptides produced in PVX::Avr9-infected tobacco contained one GlcNAc residue, whereas approximately one-half of the AVR9 isolated from Avr9-transgenic tomato contained one GlcNAc residue. The presence of nonglycosylated AVR9 peptides and the unusual attachment of only one GlcNAc residue suggest that glycosylation occurs partially, or that deglycosylation of AVR9 by glycosidases occurs in the apoplast. Deglycosylation of foreign peptides is a general phenomenon in plants (Cervone et al., 1989).

Although the necrosis-inducing activities of nonglycosylated and glycosylated AVR9 peptides are similar, they show a large difference in binding affinity. Nonglycosylated and glycosylated wild-type AVR9 (Table IV) show a 24-fold difference in affinity, whereas nonglycosylated R08K and glycosylated R08K (Table IV) show a 42-fold difference in affinity. It should be remembered that in the studies reported here, AVR9 is transiently expressed in tobacco by the PVX expression vector. It is uncertain whether glycosylation of AVR9 plays a role in the natural C. fulvum-tomato interaction. The observed difference in binding affinity between glycosylated and nonglycosylated peptides could be caused by either a higher solubility of glycosylated peptides in the in vivo assays or a lower solubility in the in vitro assays, in which the solubilized membranes contribute to a hydrophobic environment. For the cystine-knotted peptide ω-conotoxin, which is structurally related to AVR9, structure-function studies showed a poor correlation between binding to the N-type Ca channel and the channel-blocking activity (Lew et al., 1997). The authors hypothesized that this could be attributable to an altered conformation of the Ca channel in the in vitro assays. This might also partly explain the discrepancies between in vitro binding and in vivo activity of some mutant AVR9 peptides. Alternatively, discrepancies between binding and activity may suggest the existence of a second binding site that is insensitive to glycosylation of AVR9. This putative second receptor, which has remained undetected in our binding assays at present, could be the product of the Cf-9 R gene.

Inactive AVR9 Peptides

Not only the glycosylated versus the nonglycosylated peptides show a discrepancy between binding affinity and necrosis-inducing activity. The F21A and L24S mutants did not induce necrosis upon injection into MM-Cf9 leaflets up to concentrations of 100 and 30 μm, respectively, but still showed a low affinity to the binding site. Both peptides bound to the AVR9-binding site with a slightly lower affinity than the nonglycosylated (for F21A) or the glycosylated (for L24S) AVR9 mutants that exhibited low necrosis-inducing activity. Possibly, the in vivo binding conditions may not be optimal for F21A and L24S, their affinity may be too low to induce necrosis, or they may be degraded by tomato proteases before reaching the binding site. The latter suggestion might apply for the F21A peptide, which has similar affinity to the binding site as F10A, but no necrosis-inducing activity. Again, the presence of an as-yet-undetected second binding site may also explain the differences between binding affinity and necrosis-inducing activity of the two peptides.

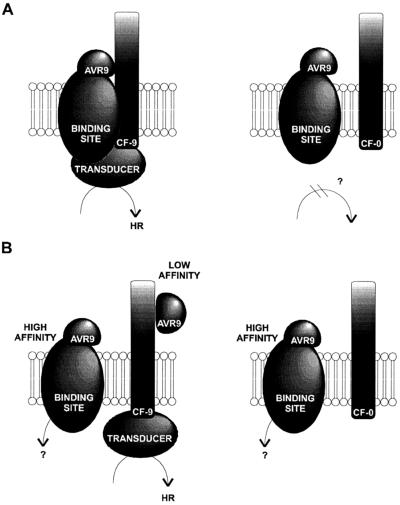

Models for the Role of the AVR9-Binding Site in Necrosis Induction

Here, we present two models of the role of the binding site in initiating the AVR9-CF-9-dependent HR. Based on the positive correlation between binding affinity and necrosis-inducing activity of AVR9 peptides (found in a certain range of concentrations), we postulate that the high-affinity binding site for AVR9 is required to initiate the resistance response in tomato plants carrying the Cf-9 R gene. However, based on the results presented, we cannot fully exclude the presence of an as-yet-undetected second binding site.

The initial model for the recognition of elicitors by resistant plants is the elicitor-receptor model, which assumes that R genes encode the receptors for the Avr-gene products (Gabriel and Rolfe, 1990). This model is unlikely for the AVR9-CF-9 interaction because we have shown that binding of AVR9 is not restricted to tomato plants carrying the Cf-9 R gene (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). As yet, the elicitor-receptor model has been verified only for the interaction between tomato and the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato, in which the resistance gene product Pto kinase and the avirulence gene product AvrPto were shown to interact in a two-hybrid assay (Scofield et al., 1996; Tang et al., 1996). It has been proposed that AvrPto mediates the interaction between the Pto kinase and the LRR-containing protein Prf, thereby activating the signal cascade. Similarly, binding of AVR9 could mediate the interaction between the AVR9-binding protein and the LRR protein CF-9. This is schematically represented in Figure 4A. Possibly, binding induces recruitment of CF-9 into the binding-site-AVR9 complex. The resulting CF-9-AVR9-binding-site complex will subsequently initiate the resistance signal cascade. This model is supported by the correlation between necrosis-inducing activity of several AVR9 peptides and their affinity to the high-affinity binding site, indicating that this binding site may be required for the induction of the resistance response.

Figure 4.

Two models of the perception of AVR9 by resistant (left, Cf-9) and susceptible (right, Cf-0) tomato genotypes. A, Model in which AVR9 binding mediates the interaction between CF-9 and the binding-site-AVR9 complex. B, Alternative model, in which the high-affinity binding site is not required to initiate HR, but HR is induced by low-affinity binding of AVR9 to CF-9.

However, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that CF-9 directly interacts with AVR9, as presented in Figure 4B. Given the observed correlation between affinity and activity of AVR9 peptides, this model would imply that the amino acids of AVR9 required to interact with the high-affinity binding site are similar to those required for binding to CF-9. However, a second binding site has never been detected in our binding assays using varying binding conditions and concentrations of 125I-AVR9 up to 10 nm. This may be because of its low affinity for AVR9 (Kd > 100 nm) or to a low abundance (<80 fmol/mg microsomal protein). A low abundance of CF-9 would be in agreement with the low abundance of Cf-9 mRNA (Jones et al., 1994).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Bianca van Haperen performed the binding experiments using tobacco membranes. We thank Rob van der Hoeven (Leiden, The Netherlands) for performing the ES-MS experiments. Renier van der Hoorn assisted in preparing Figure 4. Matthieu H.A.J. Joosten and Robert C. Schuurink are acknowledged for critically reading the manuscript. Jacques J.M. Vervoort (Wageningen, The Netherlands) is acknowledged for performing 1D-NMR and CD spectroscopy and for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations:

- AF

apoplastic fluid

- CD

circular dichroism

- 1D and 2D

one- and two-dimensional, respectively

- ES

electrospray

- HR

hypersensitive response

- LpH-PAGE

low-pH PAGE

- LRR

Leu-rich repeat motif

- MM

MoneyMaker

- PVX

potato virus X

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Netherlands Technology Foundation and coordinated by the Life Sciences Foundation through a grant provided to M.K.-G. and P.J.G.M.d.W. R.V. was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization Long-Term Fellowship and a Human Capital and Mobility grant (no. CHRX-CT93-0170) supplied by the European Commission (EC), and H.W.v.d.H. was supported by a EC Biotech grant (no. BIO4 CT96 0515). E.M. acknowledges support from European Union-Training and Mobility of Researchers (grant no. CHGE-CT94-0061).

LITERATURE CITED

- Bent AF, Kunkel BN, Dahlbeck D, Brown KL, Schmidt R, Giraudat J, Leung J, Staskawicz BJ. Rps2 of Arabidopsis thaliana: a leucine-rich repeat class of plant disease resistance genes. Science. 1994;265:1856–1860. doi: 10.1126/science.8091210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgrove SR, Simonich MT, Smith NM, Sattler A, Innes RW. A disease resistance gene in Arabidopsis with specificity for two different pathogen avirulence genes. Plant Cell. 1994;6:927–933. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.7.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervone F, Hahn MG, De Lorenzo G, Darvill A, Albersheim P. Host-pathogen interactions. XXXIII. A plant protein converts a fungal pathogenesis factor into an elicitor of plant defense responses. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:542–548. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.2.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J-Y, Canals F, Schindler P, Querol E, Avilés FX. The disulfide folding pathway of potato carboxypeptidase inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22087–22094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S, Kavanagh T, Baulcombe D. Potato virus X as a vector for gene expression in plants. Plant J. 1992;2:549–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1992.t01-24-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL. The enigmatic avirulence genes of phytopathogenic bacteria. In: Dangl JL, editor. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 192. Bacterial Pathogenesis of Plants and Animals: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1994. pp. 99–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit PJGM, Hofman AE, Velthuis GCM, Kuc JA. Isolation and characterization of an elicitor of necrosis isolated from intercellular fluids of compatible interactions of Cladosporium fulvum (syn. Fulvia fulva) and tomato. Plant Physiol. 1985;77:642–647. doi: 10.1104/pp.77.3.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit PJGM, Spikman G. Evidence for the occurrence of race- and cultivar-specific elicitors of necrosis in intercellular fluids of compatible interactions of Cladosporium fulvum and tomato. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1982;21:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Flor HH. Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1971;9:275–296. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel DW, Rolfe BG. Working models of specific recognition in plant microbe interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1990;28:365–391. [Google Scholar]

- Grant MR, Godiard L, Straube E, Ashfield T, Lewald J, Sattler A, Innes RW, Dangl JL. Structure of the Arabidopsis Rmp1 gene enabling dual specificity disease resistance. Science. 1995;269:843–846. doi: 10.1126/science.7638602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honée G, Melchers LS, Vleeshouwers VGGA, van Roekel JSC, de Wit PJGM. Production of the AVR9 elicitor from the fungal pathogen Cladosporium fulvum in transgenic tobacco and tomato plants. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;29:909–920. doi: 10.1007/BF00014965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme EC, Birdsall NJM. Strategy and tactics in receptor-binding studies. In: Hulme EC, editor. Receptor-Ligand Interactions: A Practical Approach, Vol 1. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 63–176. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs NW. Cystine knots. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:391–395. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Jones J. The role of leucine-rich repeat proteins in plant defences. Adv Bot Res. 1996;24:91–167. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DA, Thomas CM, Hammond-Kosack KE, Balint-Kurti PJ, Jones JDG. Isolation of the tomato Cf-9 gene for resistance to Cladosporium fulvum by transposon tagging. Science. 1994;266:789–793. doi: 10.1126/science.7973631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten MHAJ, Cozijnsen AJ, de Wit PJGM. Host resistance to a fungal tomato pathogen lost by a single base-pair change in an avirulence gene. Nature. 1994;367:384–386. doi: 10.1038/367384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten MHAJ, Vogelsang R, Cozijnsen TJ, Verberne MC, de Wit PJGM. The biotrophic fungus Cladosporium fulvum circumvents Cf-4-mediated resistance by producing unstable AVR4 elicitors. Plant Cell. 1997;9:367–379. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe B, Deisenhofer J. A structural basis of the interactions between leucine-rich repeats and protein ligands. Nature. 1995;374:183–186. doi: 10.1038/374183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooman-Gersmann M, Honée G, Bonnema G, de Wit PJGM. A high-affinity binding site for the AVR9 peptide elicitor of Cladosporium fulvum is present on plasma membranes of tomato and other solanaceous plants. Plant Cell. 1996;8:929–938. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.5.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooman-Gersmann M, Vogelsang R, Hoogendijk ECM, de Wit PJGM. Assignment of amino acid residues of the AVR9 peptide of Cladosporium fulvum that determine elicitor activity. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1997;10:821–829. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach JE, White FF. Bacterial avirulence genes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1996;34:153–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.34.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew MJ, Flin JP, Pallaghy PK, Murphy R, Whorlow SL, Wright CE, Norton RS, Angus JA. Structure-function relationships of ω-conotoxin GVIA: synthesis, structure, calcium-channel binding, and functional assay of alanine-substituted analogues. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12014–12023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GB, Brommonschenkel SH, Chungwongse J, Frary A, Ganal MW, Spivey R, Wu T, Earle ED, Tanksley SD. Map-based cloning of a protein kinase gene conferring disease resistance in tomato. Science. 1993;262:1432–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.7902614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett HS, Watanabe Y, Beachy RN. Identification of the TMV replicase sequence that activates the N gene-mediated hypersensitive response. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1997;10:709–715. [Google Scholar]

- Reisfeld RA, Lewis UJ, William DE. Disk electrophoresis of basic proteins and peptides on polyacrylamide gels. Nature. 1962;195:281–283. doi: 10.1038/195281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohe M, Gierlich A, Hermann H, Hahn M, Schmidt B, Rosahl S, Knogge W. The race-specific elicitor, NIP1, from the barley pathogen, Rhynchosporium secalis, determines avirulence on host plants of the Rrs1 resistance genotype. EMBO J. 1995;14:4168–4177. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scofield SR, Tobias CM, Rathjen JP, Chang JH, Lavelle DT, Michelmore RW, Staskawicz BJ. Molecular basis of gene-for-gene specificity in bacterial speck disease of tomato. Science. 1996;274:2063–2065. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla P, Bruix M, Santoro J, Gago F, Garcia AG, Rico M. Three-dimensional structure of ω-conotoxin GVIA determined by 1H NMR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:1238–1244. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staskawicz BJ, Ausubel FM, Baker BJ, Ellis JG, Jones JDG. Molecular genetics of plant disease resistance. Science. 1995;268:661–667. doi: 10.1126/science.7732374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyperski T, Güntert P, Otting G, Wüttrich K. Determination of scalar coupling constants by inverse Fourier transformation of in-phase multiplets. J Magn Reson. 1992;99:552–560. [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Frederick RD, Zhou J, Halterman DA, Jia Y, Martin GB. Initiation of plant disease resistance by physical interaction of AvrPto and Pto kinase. Science. 1996;274:2060–2063. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraporewala ZF, Culver JN. Identification of an elicitor active site within the three-dimensional structure of the tobacco mosaic tobamovirus coat protein. Plant Cell. 1996;8:169–178. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CM, Jones DA, Parniske MP, Harrison K, Balint-Kurti PJ, Hatzixanthis K, Jones JDG. Characterization of the tomato Cf-4 gene for resistance to Cladosporium fulvum identifies sequences that determine recognitional specificity in Cf-4 and Cf-9. Plant Cell. 1997;9:2209–2224. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.12.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Ackerveken GFJM, van Kan JAL, de Wit PJGM. Molecular analysis of the avirulence gene Avr9 of the fungal pathogen Cladosporium fulvum fully supports the gene-for-gene hypothesis. Plant J. 1992;2:359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1992.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Ackerveken GFJM, Vossen P, de Wit PJGM. The AVR9 race-specific elicitor of Cladosporium fulvum is processed by endogenous and plant proteases. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:91–96. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kan JAL, van den Ackerveken GFJM, de Wit PJGM. Cloning and characterization of cDNA of avirulence gene Avr9 of the fungal pathogen Cladosporium fulvum, causal agent of tomato leaf mold. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1991;4:52–59. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-4-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort J, van den Hooven HW, Berg A, Vossen P, Vogelsang R, Joosten MHAJ, de Wit PJGM. The race-specific elicitor AVR9 of the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum: a cystine-knot protein. Sequence-specific 1H NMR assignments, secondary structure and global fold of the protein. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vliegenthart JFG, Montreuil J. Primary structure of glycoprotein glycans. In: Montreuil J, Vliegenthart JFG, Schachter H, editors. Glycoproteins. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1995. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. The chemical shift index: a fast and simple method for the assignment of protein secondary structure through NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1647–1651. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]