Abstract

Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia worldwide. In Hispanic populations there are few validated tests for the accurate identification and diagnosis of AD. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale is an internationally recognized questionnaire used to stage dementia. This study's objective was to develop a linguistic adaptation of the CDR for the Puerto Rican population.

Methods

The linguistic adaptation consisted of the evaluation of each CDR question (item) and the questionnaire's instructions, for similarities in meaning (semantic equivalence), relevance of content (content equivalence), and appropriateness of the questionnaire's format and measuring technique (technical equivalence). A focus group methodology was used to assess cultural relevance, clarity, and suitability of the measuring technique in the Argentinean version of the CDR for use in a Puerto Rican population.

Results

A total of 27 semantic equivalence changes were recommended in four categories: higher than 6th grade level of reading, meaning, common use, and word preference. Four content equivalence changes were identified, all focused on improving the applicability of the test questions to the general population's concept of street addresses and common dietary choices. There were no recommendations for changes in the assessment of technical equivalence.

Conclusions

We developed a linguistically adapted CDR instrument for the Puerto Rican population, preserving the semantic, content, and technical equivalences of the original version. Further studies are needed to validate the CDR instrument with the staging of Alzheimer's disease in the Puerto Rican population.

Keywords: Dementia rating scales, Hispanics, Validation

Introduction

Prevalence estimates of mental illnesses in the United States (U.S.) show Alzheimer's disease (AD) to be the most common form of dementia (1,2). A recent statistical report of data on AD estimated over 5 million cases in 2008 (3). Given this figure, 13% of the U.S. population older than 65 years suffers from the disease. This prevalence is expected to reach 7.7 million in 2030.

In Puerto Rico, Alzheimer's disease ranked fifth among causes of mortality in 2004 (4). Although a completed prevalence study of AD is lacking in Puerto Rico, there is an ongoing prevalence study that will eventually supply this information (5). Extrapolating the U.S. prevalence data to Puerto Rico's elderly population (aged over 65) in 2008, we estimate there are 70,000 cases of AD on the Island. In view of the increasing Puerto Rican population aged over 65 years and the likely increased prevalence of AD, there is urgent need for valid and reliable methods for the early diagnosis and staging of dementia in this population.

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, developed at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, was first published by Hughes and coworkers in 1982 (6). Originally developed to measure the staging of dementia in Alzheimer's disease patients, it has been extended to other dementias and is used worldwide in memory assessment clinics, research studies, and clinical trials of potential therapeutic agents.

The CDR consists of independent semi-structured interviews that usually take place in a clinical setting performed face to face with the patient. Prior to the patient's interview a reliable informant (usually the spouse or a close family member) is interviewed to confirm the patient's cognitive abilities. It is considered a global clinical scale as it also measures social, behavioral, and functional changes in the patient's accustomed activities. It has several advantages: it is independent from other psychometric testing; it does not require a baseline evaluation; and the individual serves as his/her own control. It has been found to correlate with histological markers of dementia severity (7) and has a predictive value in AD longitudinal studies (8). CDR administration requires special training, as its high validity and reliability rely on the skills and judgment of the interviewer to obtain pertinent information (9).

The CDR Scale

The CDR evaluates cognitive performance in six domains: three cognitive (memory, orientation, and judgment and problem solving) and three functional (community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care). A worksheet includes the questions required for each domain evaluation individually rated on a 5-point scale, according to the level of impairment. A score of 0 suggests no impairment; a score of 0.5 indicates very mild impairment; a score of 1 indicates mild impairment; a score of 2 indicates moderate impairment; and a scale of 3 indicates severe impairment. Personal care is rated on a 4-point scale as there is no distinction, as above, between the no (0) and the very low (0.5) levels of impairment (10). The sum of the individual category ratings for each domain (sum of boxes) provides a quantitative expansion of the CDR that ranges from 0 (0 × 6 when there is no impairment in any domain) to 18 (3 × 6 when there is maximum impairment in all domains) (7).

A global score is then derived using the individual ratings in the six domains applying predefined rules. A global CDR score is also rated on a 5-point scale. A score of 0 suggests absence of dementia; 0.5, questionable or very mild dementia; 1, mild dementia; 2, moderate dementia; and 3, severe dementia (10). The 0.5 score is divided into two subcategories, very mild or incipient dementia and uncertain dementia (11). These subcategories include patients who have some cognitive impairment but not severe enough to interfere with their daily functions, and those who suffer another condition, such as depression, that may be the cause of their impairment. Some clinical studies have included two additional staging levels: 4 for patients with profound dementia and 5 for those with terminal dementia (12).

The CDR, revised by Morris in 1993, is currently used for the clinical and neuropsychological assessment of AD and other dementias of the elderly (10). This version has been translated into Bulgarian, Chinese, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, and Spanish (13,14). Although there are several Spanish translations of the CDR, none has been linguistically adapted or validated for the Puerto Rican population. Cross-cultural research literature shows that cultural and linguistic differences may affect the interpretation of quantitative neuropsychological instruments, thus limiting the reliable and valid interpretation of the scale when applied to a particular population. Even when translated versions are in a population's native language, there can be cultural differences in the verbal expression of concepts, in meaning, and in relevance that may affect confidence in the validity of results obtained using the translation (15).

Cultural adaptation of a tool involves the production of an equivalent instrument for a target population, one that measures the same phenomenon in both the original and the target cultures. The first phase of the process includes a translation of words and sentences from the original language to another and then further linguistic adaptation to the cultural context of the target population to ensure that the new version is conceptually and culturally pertinent. The second phase of the cultural adaptation includes a validation phase during which the instrument is proved to be psychometrically equivalent to the original version (16, 17).

In our study, the linguistic adaptation and psychometric validation of the CDR scale was aimed at providing a valid and reliable tool for the expansion of research efforts and early diagnosis of AD-related conditions in Puerto Rican Hispanics, allowing the comparison of results with other populations for whom the instrument has already been culturally adapted.

Materials and Methods

Preparatory Phase

The Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects (IRB) of the Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico approved the pilot project in January 2007. The first author (IOJ) was trained and certified as a CDR rater by the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. The ADRC gave permission to adapt the CDR instrument for use in a Puerto Rican population.

A translator was recruited to evaluate several Spanish-language versions of the CDR and to recommend the one closest to Puerto Rican Spanish. The recommendation was based on similarities in vocabulary between the chosen version and the Spanish used in Puerto Rico. The Argentinean version translated by Mapi Research Institute (Mapi) was recommended with replacement of some words with their Puerto Rican Spanish equivalents.

Linguistic Adaptation

Mapi, an internationally recognized institution in France, has ample expertise in the translation of patient-reported and clinical assessment instruments for cross-cultural use. The translation process used by Mapi includes the clarification of concepts investigated in the original instrument to ensure they are reflected appropriately in the target language, forward and back-translations to the target and source language, and a pilot testing (18).

Cross-cultural research methodology identifies five major dimensions to be considered in the equivalence process: 1) content equivalence (relevance of the content of items to each culture); 2) semantic equivalence (similar meaning of items in each culture); 3) technical equivalence (comparable method of measuring techniques in each culture); 4) criterion equivalence (capacity to measure the same phenomena among cultures); and 5) conceptual equivalence (capacity to measure the same basic construct among cultures) (19,20). The Mapi approach to translation for the Argentinean version preserved content, conceptual, and technical equivalence of the original CDR English version (18).

During the initial phase of the linguistic adaptation of the CDR to be used in Puerto Rico, a professional translator evaluated the semantic equivalence of Argentinean Spanish and Puerto Rican Spanish. During the translator's first revision of the CDR Argentinean version, some words were substituted for the corresponding words or phrases used in Puerto Rico. For example, because the word birome is not used in Puerto Rico, it was replaced by bolígrafo, the word commonly used for a ballpoint pen. The word geriátrico was replaced by hogar de ancianos, the common name in Puerto Rico for nursing homes, and premórbida, a medical term requiring a higher than 6th grade level of reading, was replaced by the phrase antes de enfermar, which means “before becoming sick”.

Focus Group

The focus group consisted of 7 persons (6 women and 1 man), ages 20 to 75 years, who were life-long residents of Puerto Rico. They considered themselves to be completely bilingual and represented diverse occupations (clinical psychologist, nurse, geriatric pharmacist, accountant, secretary, laboratory technician, and a student). The translator monitored the process and the PI served as moderator. After the individual evaluation, an additional 1½ hour group discussion followed. The focus group recommendations for changes coincided with many of the words the translator had identified as problematic in the Argentinean version. A discussion followed each recommendation with ample and enthusiastic participation. Proposed changes and recommendations were approved by consensus.

Procedure

After the translator's initial revision, the modified Argentinean version was evaluated in a pilot testing using a focus group method to assess cultural relevance, clarity, and suitability of the measuring technique; group members were asked to suggest modifications and to explain why the changes were needed. A self-administered written questionnaire to evaluate each CDR item was developed in a worksheet form (Table 1). The evaluation worksheet questionnaire required each focus group evaluator to identify words, terms, or phrases not pertinent to the Puerto Rican culture and to give reasons for their choices. An evaluation of the clarity of each item was also required; if an item was considered unclear, then evaluators were asked to recommend how to improve it. The translator was an observer during the focus group discussion, having interaction with the group only when a clarification was requested or any member of the focus group asked for expert advice. The translator kept a record of the focus group evaluators' comments and opinions, and served as quality check for the appropriateness of words recommended by group members to be used in place of terms in the Argentinean version.

Table 1. Focus Group Worksheet Questionnaire to Evaluate CDR Items.

Preguntas para Evaluar la Pertinencia de la Escala de Evaluación Clínica de Demencia (CDR) a la Cultura Puertorriqueña: Evaluador #______ Este instrumento ha sido diseñado para evaluar la pertinencia cultural de la versión al español de la escala de Evaluación Clínica de Demencia (CDR) al ser comparada con la versión Argentina. Se provee además, como referencia el documento original de la prueba en inglés para que lo utilice como referencia.

| Aspectos que considera no pertinentes a la cultura puertorriqueña (palabras, términos o frases), si alguno. | Razones por las que no son pertinentes y sugerencias de adaptaciones o cambios. | Claridad 1=Es claro 2=No es claro |

Provee ejemplo de cómo la pregunta sería más clara. | Cuan adecuada es la escala con que se responde a la pregunta. 1=Adecuada 2=No adecuada |

Provee ejemplo de cómo la escala sería más adecuada. |

| Memoria | |||||

| Orientación | |||||

| Juicio y Solución de Problemas |

|||||

| Actividades Comunitarias |

|||||

| Actividades Domésticas y Pasatiempos |

|||||

| Cuidado Personal |

The information gathered from the focus group was reviewed by investigators and the translator, who together classified the proposed changes on the basis of type of change and reason for change. After this analysis, an experimental version of the CDR for Puerto Rico was developed.

Further linguistic adaptation

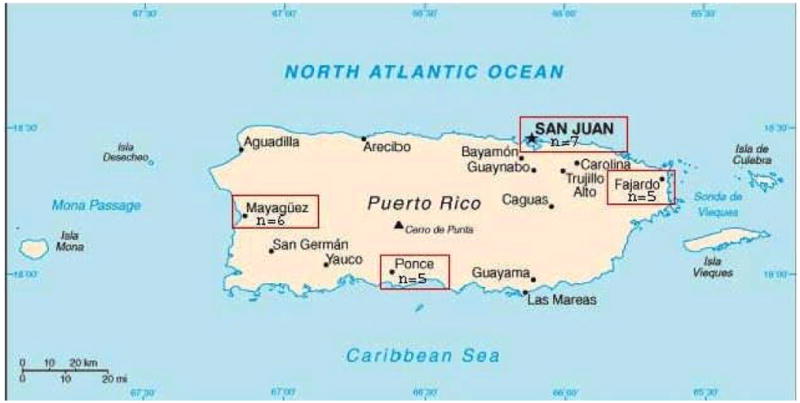

The experimental version of the CDR for Puerto Rico was used for further linguistic and cultural input. It was distributed to 23 individuals in waiting rooms for outpatient evaluations in different geographical areas of Puerto Rico located at the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus Intramural Practice at San Juan, the Hospital Interamericano de Medicina Avanzada (HIMA) San Pablo del Este at Fajardo, Dr. Pila Hospital at Ponce, and Ramón E. Betances Hospital at Mayagüez (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Community Participants from Different Geographical Areas of Puerto Rico.

Gender, age, and education of these participants are shown in Table 2. Seventy percent were female and 30% males. Their mean ages were 60.4 and 69.3 years, and the median levels of education were 7th and 8th grade, respectively.

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of Community Participants.

| Gender | Female | Male |

| N = 23 | n = 16 (70%) | n = 7 (30%) |

|

| ||

| Age, yrs. | ||

| Mean (SD) | 60.4 (13.1) | 69.3 (15.6) |

| Range | 42 - 78 | 48 -87 |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.3 (3.7) | 8.8 (3.8) |

| Median | 7th grade | 8th grade |

The 23 participants were asked to read the questionnaire and suggest changes that would improve a reader's understanding of the text. There were no time limitations for this activity. Only recommendations made by at least 8 of the 23 individuals were incorporated into the final version of the CDR for Puerto Rico.

Results

The focus group recommended 25 semantic changes from a total of 83 items. (Table 3). The semantic changes were divided into four categories depending on the reason for the change: higher than 6th grade level of reading, meaning, common use, and word preference. Four changes in content were also recommended. There were no recommendations for changes in the measuring scales used in the questionnaire. The presentation format and the 5-point scoring system were considered simple and easy to perform.

Table 3. Translator and Focus Group Modifications to the CDR Argentinean Spanish Version, March 2007.

| Categories | Argentinean Version | Modifications | Reason(s) for change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher than 6th grade level of reading | esporádico* | ocasional | Synonyms. “Esporádico” requires higher than 6th grade level of reading. |

| cotidianas* | diarias | Synonyms. “Cotidianas” requires higher than 6th grade level of reading. | |

| premórbida* | antes de enfermar | Synonyms. “Premórbida” requires higher than 6th grade level of reading; more a technical word used in medicine; would not be understood by lay public. | |

| sinfonía* | concierto | “Concierto” is a more general term used when speaking about going to an event at which music is played; “sinfonía” refers more specifically to a music category. | |

| Meaning | birome* | bolígrafo | “Birome” is the Argentinean word referring to a ballpoint pen. It is not used in other Spanish-speaking countries. |

| verduras* | vegetales | In the statement used, the examples “zanahoria-lechuga” are not classified as verduras in Puerto Rico. The term “verduras” is the name given to certain vegetables with edible roots. It is not used to name green leafy vegetables such as lettuce, broccoli, and others. | |

| posición social* | situación actual | “Posición social” refers to level or position in society that goes along with income, education earned, and other characteristics that confer standing. “Situación actual” refers to the situation of a person at a certain moment or present time. | |

| Common use | raramente* | rara vez | Synonyms. “Rara vez” is more common in Puerto Rico; it is similar to saying in English, rarely or on rare occasions. |

| casamiento* familiar | boda familiar | Synonyms. “Boda” is the word commonly used in Puerto Rico. | |

| fecha de casamiento* | fecha de su boda | Same as above. | |

| cañerías* | tuberías | Synonyms. “Tuberías” is the word used in Puerto Rico. | |

| geriátrico* | hogar de ancianos | Both words are used for nursing homes. “Hogar de ancianos” is the word commonly used in Puerto Rico. | |

| estantería* | librero | Synonyms. “Librero” is the word commonly used in Puerto Rico. | |

| barrio | vecindario | Synonyms. “Vecindario” is more common in Puerto Rico. | |

| electrodomésticos* | enseres eléctricos | Synonyms. “Enseres eléctricos” is the term commonly used in Puerto Rico. | |

| Word preference | se encuentra | está | Synonyms. “Está” is active voice. |

| se le debe dar de comer* | tiene que ser alimentado | “Tiene que ser alimentado” is the active voice; gives a clearer idea that the person always needs to be fed by another one. | |

| Content | Reconquista | Unión | The address in the memory test should be pertinent to Puerto Rico. Reconquista is not a common name for a street in Puerto Rico. Unión is a common name for a street in Puerto Rico. |

| Buenos Aires | Mayagüez | The address in the memory test should be pertinent to Puerto Rico. Mayagüez is a town on the west coast of the Island. | |

| rábano | zanahoria | “Rábano” is not a vegetable consumed by the general population in Puerto Rico. | |

| coliflor | lechuga | “Coliflor” is not a vegetable consumed by the general population in Puerto Rico. |

Translator initial modifications

Ref: Diccionario de la Lengua Española, Real Academia Española

María Moliner, Diccionario de Uso del Español. Madrid: Gredos, 1998

The educational level of understanding for the translation was established at the 6th grade level. Words requiring a higher than 6th grade level of reading were identified and substitutes were recommended. Words that would not be understood, either because they are not commonly used or because they denote a different concept in the Puerto Rican culture, were classified as changes in meaning. Synonyms, commonly used in Puerto Rico by the lay public, were classified as common use changes. Word preference mostly concerned use of the active voice, which the focus group considered to be clearer and easier to understand than passive voice.

Further linguistic adaptation followed the additional evaluation of the 23 individuals located in different areas of Puerto Rico who gave feedback on the focus group-modified version. Specifically, two additional semantic changes and five items for clarification were recommended (Table 4). For example, most of the participants did not understand the word esfínteres, and control del intestino y de la orina was recommended in its place. Clarification of content, as with the term sólidos simples, included the addition of examples such as cremas, viandas majadas, sopas. Another example of clarification of meaning is the use of ahora with un tiempo atrás, wording that makes it explicit that past activity and present activity are to be compared.

Table 4. Recommendations from community participants from different areas of Puerto Rico, July - October 2007.

| Categories | Focus group version | Recommendations | Reason (s) for change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher than 6th grade level of reading | Control de esfínteres | Control del intestino y la vejiga | “Esfínteres” requires higher than 6th grade level of reading. It is not understood by lay public. |

| Word preference | empresariales | de negocio | Synonyms. “De negocio” is a term more commonly used by lay public. |

| Clarification | Evalúe la capacidad de el/ella para…. | Evalúe la capacidad de el/ella para…. ahora con un tiempo atrás. | Clarifies the question which requires a comparison. |

| ¿Puede él/ella Comprender situaciones o explicaciones? | ¿Puede él/ella comprender situaciones o explicaciones sobre algún asunto que se le presente? | Clarifies the question. | |

| Sólidos simples | Incluir ejemplos: cremas, viandas majadas, sopas | Helps the reader understand what sorts of foods are considered simple solids. | |

| doméstica | En el hogar | Synonyms. “En el hogar” is used more commonly by lay public. | |

| pasatiempos | Add “intereses” | Clarifies the required information; not everybody has a hobby, but may have activities that evoke enthusiasm. |

Discussion

It is recognized in cross-cultural research literature that cultural and linguistic differences may affect the interpretation of quantitative neuropsychological instruments (19). Translation of an instrument is not enough to obtain language equivalence when the translated instrument is applied to a population from a different culture. A rigorous, systematic approach to the translation and validation process through a cross-cultural adaptation is needed to assure the equivalency necessary for clinical or research application (19).

Cross-cultural research methodology identifies five major equivalences to be considered in the adaptation process: content, semantic, technical, criterion, and conceptual. The Argentinean Spanish CDR version went through a detailed linguistic validation process in Mapi Research Institute comparable to the one proposed in the literature. In light of this rigorous and systematic procedure, it was decided to use the Argentinean translation for a linguistic adaptation to the Spanish used in Puerto Rico. Even though the semantic and content equivalences were maintained during the Mapi translation of the English language CDR into Argentinean Spanish, rewording of a number of items and changes in content were required to maintain the same meaning and relevance of content of the original English language version in the linguistic adaptation for the Puerto Rican population.

The CDR instrument was subjected to content, semantic, and technical assessment, and changes were recommended, accordingly, for its linguistic adaptation. The data obtained during this process supported the linguistic equivalence as the first step for the cultural adaptation of the instrument to the Puerto Rican population. The criterion and conceptual equivalences will be accomplished in the second phase of this study to complete the cultural adaptation to establish the psychometric properties of the instrument.

The focus group methodology was an effective way to obtain input about cultural relevance, clarity, and suitability of the format and measuring technique of the Argentinean version of the CDR for use in a Puerto Rican population. The worksheet developed to obtain feedback from focus group evaluators facilitated the needed systematic approach to data collection and interpretation, and it provided the structure for the focus group discussion. The diverse composition of the focus group with its broad range of ages and occupations provided wide-ranging input regarding the relevance of each item to the Puerto Rican culture. The evaluators' high proficiency in Spanish and English helped ensure that the words used were unambiguous, simple, and comprehensible to the Puerto Rican population without changing the original meaning.

The focus group identified words not commonly used in Puerto Rico, words meaning something different in Puerto Rico than in Argentina, words requiring a higher than 6th grade reading level, verbs that could be changed to active voice to facilitate the reader's understanding, and some content changes for phrases not pertinent to the culture. Substitutions were made so that the text was better suited to Puerto Ricans. These changes generated a more culturally suitable questionnaire, which could be understood by the majority of people, while the original concepts were preserved. Although the educational level of the 23 participants from the community was diverse, the 6th grade level of reading established for the translation worked for all members of the sampled population.

The further linguistic adaptation in the community also offered the opportunity to assess the cultural relevance of the CDR focus group version in different towns and to factor in possible idiomatic regional differences. Native Spanish-speaking people from different areas of Puerto Rico mainly suggested rewording items to use common words or adding words or phrases to clarify a concept. This further linguistic adaptation made the questionnaire more comprehensible to Puerto Ricans.

A limitation of the study is that the linguistic adapted CDR version applies only to native Spanish speaking Puerto Ricans. As mentioned before, the focus group and the individuals who gave feedback on the focus group CDR modified version were only native Spanish speaking Puerto Ricans. The study did not considered input from other Hispanics or Latino sub groups. For a cross-cultural equivalence instrument, which could be applied to these sub groups, a linguistic and cultural adaptation process should be implemented including them. Nevertheless, the linguistic adapted version obtained in this study provides a foundation for future cross-cultural efforts.

In conclusion, we applied cross-cultural research principles for the linguistic adaptation of the CDR scale to the Puerto Rican population. Key elements were a previous translation by Mapi, focus group evaluation, and input from persons living in different parts of the Island. Through this process, we obtained a linguistically adapted instrument for the Puerto Rican population while preserving the semantic, content, and technical equivalences of the original version. This is an important first step to establish the psychometric validity of the instrument upon completion of its cultural adaptation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dyhalma Irizarry, PhD, Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico for the revision of the manuscript, and Cruz M. Nazario, PhD, Graduate School of Public Health, and José R. Rodríguez, PhD, Río Piedras Campus, for their professional advice on the focus group methodology. The first author also thanks John C. Morris, MD, at the Washington University Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri, for her Clinical Dementia Rating training experience. This research is in partial fulfillment for the requisites of the Postdoctoral Master in Science in Clinical Research degree of Ilia Oquendo-Jiménez, PhD, at the Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico.

Funding: This investigation was partially supported by Grant Number R25 RR17589, RCMI Clinical Research Infrastructure Initiative (RCRII) Award, P20 RR011126, from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), National Institutes of Health, and S11 NS46278.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of Dementia in the United States: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29:125–132. doi: 10.1159/000109998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, et al. Alzheimer's disease in the U.S population: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures 2008. Alzheimer's Association; Chicago, Ill: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Informe Anual Estadísticas Vitales 2005. Departamento de Salud, Estado Libre Asociado; Puerto Rico: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JH, Barral S, Cheng R, Chacon I, et al. Age-at-onset linkage analysis in Caribbean Hispanics with familial late-onset Alzheimer's Disease. Neurogenetics. 2008 Feb;9(1):51–60. doi: 10.1007/s10048-007-0103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, et al. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg L, McKeel DW, Jr, Miller JP. Clinicopathological studies in cognitive healthy aging and Alzheimer' disease: relation of histologic markers to dementia severity, age, sex, and apolipoprotein E genotype. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:395–401. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg L, Danziger WL, Storandt M, et al. Predictive features in mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurology. 1984;34:563–569. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JC, Ernesto C, Schafer K, et al. Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies: the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study experience. Neurology. 1997;48:1508–1510. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, et al. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001 Mar;58(3):397–405. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JC, Borson S, Scanlan JM. Stage-specific prevalence of behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer's disease in a multi-ethnic community sample. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8:123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) http://cerad.mc.duke.edu/

- 14.Mapi Research Institute. http://www.mapi-institute.com/home [March 5, 2009]

- 15.Nelson MA, Palchanes K. A Literature Review of the Critical Elements in Translation Theory. J of Nurs Scholarship. 1994;26(2):113–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1994.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross- cultural research. J Cross-Cultural Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bracken BA, Barona A. State of the Art Procedures for Translating, Validating and Using Psychoeducational Tests in Cross –cultural Assessment. School Psychology International. 1991;12:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mapi Research Institute. http://www.mapi-institute.com/linguistic-validation [March 5, 2009]

- 19.Flaherty JA, Gaviria FM, Pathak D, et al. Developing instruments for cross-cultural psychiatric research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988 May;176(5):257–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matías-Carrelo L, Chavez LM, Negrón G, et al. The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of five outcome measures. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003;27:291–313. doi: 10.1023/a:1025399115023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]