To the Editor:

We congratulate Hoang et al1 from the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study on their article reporting a significant association between low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels and depression among the largest group of individuals in whom this potential link has been explored to date. The fact that this study was done as part of a medical student summer research program makes it even more impressive. In the same issue of Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Chamberlain et al2 report that among a cohort of patients with preexisting cardiovascular (CV) disease, depression independently predicted hospitalization and all-cause mortality over a 17-year follow-up period. We have recently documented strong independent associations between low vitamin D levels and adverse CV events,3-5 and some meta-analyses show that vitamin D supplementation appears to significantly lower all-cause mortality,6 whereas others do not.7 Thus, it is biologically plausible that vitamin D deficiency–induced depression may, in part, be responsible for increased CV risk associated with low vitamin D levels. Additionally, the tendency for depressed patients to stay indoors and be physically inactive (both risk factors for vitamin D deficiency) may lead to low vitamin D levels, which, in turn, are associated with increased CV risk.2 Although the study from Hoang et al1 demonstrates that the association between low 25(OH)D levels was independent of physical activity, we were surprised that these Cooper Center Longitudinal Study data were also not corrected for precisely measured levels of cardiorespiratory fitness.

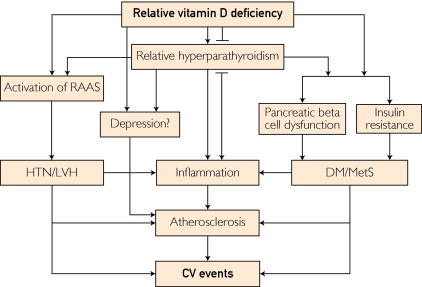

Vitamin D deficiency, besides being associated with depression, appears to increase the risk of developing inflammation, insulin resistance, diabetes, and atherosclerosis, and also activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which predisposes to hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy.3-5 All of these consequences of vitamin D deficiency, including depression, can adversely affect CV health and longevity (Figure).

FIGURE.

Potential mechanisms for CV effects of vitamin D deficiency. CV = cardiovascular; DM = diabetes mellitus; HTN = hypertension; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy; MetS = metabolic syndrome; RAAS = renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

From J Am Coll Cardiol,5 with permission.

An abnormally low vitamin D level, as defined by a serum 25(OH)D level less than or equal to 20 ng/mL, is present in 42% of the overall American adult population, 82% of black individuals, and 69% of the Hispanic population.3 The average 25(OH)D level in adults is 20 ng/mL8; a long-term daily intake of an additional 100 IU of vitamin D will increase this level by only about 1 ng/mL.3-5 Thus, supplementing the diet by the 600 to 800 IU daily as recommended by the Institute of Medicine's new guidelines9 would be expected to raise adult Americans' mean vitamin D levels to 26 to 28 ng/mL, which is still in the insufficient range (<30 ng/mL). Recently, the Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines10 suggested doses of 1000 to 2000 IU of vitamin D3 daily, which are much more likely to achieve a 25(OH)D level of at least 30 ng/mL.

Insufficient vitamin D causes musculoskeletal pain and weakness, and supplementing low 25(OH)D levels back into the normal ranges has been shown unequivocally to improve integrity and strength of bones and muscles and to reduce falls.4,5 Large randomized controlled trials are under way, and these should help to determine whether raising low vitamin D levels will also reduce risks for CV events, depression, and death. These results are not expected for several years (at least 3 years and possibly 5 years or more), and in the meanwhile it seems prudent to recommend a daily intake of 1500 to 2000 IU of vitamin D3 for most American adults. Recent data, including those from Mayo Clinic Proceedings,1,2 suggest that measuring vitamin D levels and normalizing deficiencies may be especially important for individuals with a history of depression and/or CV disease.

Footnotes

Dr O'Keefe is chief medical officer and founder of CardioTabs, a nutraceutical corporation that has vitamin D products.

References

- 1.Hoang M.T., Defina L.F., Willis B.L., Leonard D.S., Weiner M.F., Brown E.S. Association between low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and depression in a large sample of healthy adults: the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(11):1050–1055. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain A.M., Vickers K.S., Colligan R.C., Weston S.A., Rummans T.A., Roger V.L. Associations of preexisting depression and anxiety with hospitalization in patients with cardiovascular disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(11):1056–1062. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Keefe J.H., Lavie C.J., Holick M.F. Vitamin D supplementation for cardiovascular disease prevention. JAMA. 2011;306(14):1546–1547. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1465. author reply 1547-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J.H., O'Keefe J.H., Bell D., Hensrud D.D., Holick M.F. Vitamin D deficiency an important, common, and easily treatable cardiovascular risk factor? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(24):1949–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavie C.J., Lee J.H., Milani R.V. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: will it live up to its hype? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(15):1547–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjelakovic G., Gluud L.L., Nikolova D. Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007470.pub2. CD007470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elamin M.B., Abu Elnour N.O., Elamin K.B. Vitamin D and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1931–1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forrest K.Y., Stuhldreher W.L. Prevalence and correlates of vitamin D deficiency in US adults. Nutr Res. 2011;31(1):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross A.C., Taylor C.L., Yaktine A.L., Del Valle H.B. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holick M.F., Binkley N.C., Bischoff-Ferrari H.A. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]