Abstract

Stimuli-responsive materials are promising as smart materials for a range of applications. In this work, a photocrosslinkable, thermoresponsive macromer was electrospun into fibrous scaffolds containing gold nanorods (AuNRs). The resulting fibrous nanocomposites composed of poly (N-isopropylacrylamide-co-polyethylene glycol acrylate) (PNPA) and PEGylated AuNRs were crosslinked and swollen in water. AuNRs strongly absorb in the near infrared (NIR) region to generate heat and triggered the fiber thermal transition upon NIR exposure. During the thermal transition, scaffolds collapsed both macroscopically and microscopically, with individual fibers deswelling and pulling together. Exposure to a 1.1 W NIR laser decreased the diameter of swollen fibers by 34.7% from 1332 ± 193.3 to 868.9 ± 168.3 nm, and increased fiber density 116% from 209.5 ± 26.34 to 451.9 ± 23.68 fibers/mm. This transition was dependent on the incorporation of the AuNRs, and was utilized to trigger the release of encapsulated proteins from the nanocomposite fiber mats. The expulsion of water from fibers upon NIR exposure caused the release rate of incorporated protein to increase great than 10-fold, from 0.038 ± 0.052 without external stimulus to 0.462 ± 0.227 μg protein/mg polymer/min with NIR exposure. These results suggest that light-responsive fibrous nanocomposites can be utilized in applications such as drug delivery.

1. Introduction

Stimulus-responsive—or ‘smart’—polymers hold great promise for biomedical applications and have been widely investigated for applications from targeted drug delivery to tissue engineering to microfluidics [1]. N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAm) is a common building block for smart hydrogels, since it is hydrophilic at room temperature and its lower critical solution temperature (LCST) transition is well-characterized [2]. When the sample temperature surpasses the LCST, chains of NIPAm-based polymers undergo hydrophobic collapse. Homopolymers or copolymers of NIPAm have often been exploited as in situ gelling materials; because the base poly(NIPAm) LCST of 30–32 °C is below physiological temperature and these polymers form physical hydrogels once they are injected into an injury site and the temperature is elevated [3]. Copolymerization of NIPAm with highly hydrophilic monomers tends to increase the LCST of the resulting polymer, and this strategy has been used to form chemically crosslinked hydrogels that remain highly swollen at 37 °C [4]. These gels undergo a sharp deswelling upon additional heating, which has been utilized for temperature-controlled drug release [5].

While thermoresponsive materials are useful for in situ gelation or for applications where environmental variables can be easily controlled (e.g. microfluidics, separations), it is exceedingly difficult to produce large temperature changes in vivo to trigger the LCST transition or to control the transition of these materials with high spatial resolution. Moreover, most biological components are highly temperature-sensitive, so temperature fluctuations must be localized to prevent tissue necrosis. To circumvent this problem, one popular strategy has been to incorporate light- [6, 5] or magnetic field-responsive nanoparticles [7, 8] (NPs) into NIPAm scaffolds. Exposure to this additional stimulus causes the NPs to dissipate heat locally into the surrounding scaffold, triggering the LCST transition in a localized, spatially-defined manner. Gold NPs incorporated into polymeric networks have demonstrated robust heating platforms in response to light (i.e. the photothermal effect), and gold nanorods (AuNRs), specifically, have gained considerable attention for their ability to absorb near-infrared (NIR) light [9–11]. NIR light is of interest due to its ability to penetrate tissue, while being minimally absorbed by water and hemoglobin [12]. Consequently, it is highly desirable to develop NIR-light responsive systems that preferentially release their encapsulated contents upon NIR exposure. We recently reported a method to manipulate crosslinked polymer-AuNR composite microparticles, where NIR light triggered a temperature transition (i.e. glass transition temperature) in the microparticles, releasing encapsulated small-molecules [10, 11]. Others have utilized poly(NIPAm) derivatives with embedded gold NPs to induce drug release, though these polymer-nanoparticle composites have so far been limited almost exclusively to bulk and porous hydrogels and single-NP conjugates [13, 6, 5].

Fibrous polymeric carriers are a potentially useful class of materials for drug delivery and tissue engineering [14] and in recent years electrospun materials have emerged as alternatives for the controlled release of bioactive molecules [15–18]. A relatively simple technique for forming scaffolds composed of polymer nanofibers, electrospinning allows for the stable encapsulation of drugs or growth factors into nanofiber cores [19, 20]. These mats are also promising tissue engineering substrates, as fiber alignment has been shown to induce alignment of seeded cells [21] and their deposited extracellular matrix [22]. Aside from providing topographical cues to cells, electrospun mats are attractive because of the ease with which multiple fiber populations can be combined. Baker and coworkers simultaneously spun two fiber populations with poly(ethylene oxide) serving as a sacrificial polymer to increase the porosity of a poly(ε–caprolactone) fiber mat [23], and composites with two functional fiber types have been similarly fabricated [24]. Electrospinning has rarely been used to produce stimulus-responsive fibrous scaffolds, though the high relative surface area of fibers should impart very fast stimulus response times to electrospun scaffolds [25, 26]. Additionally, in the few reported examples of thermoresponsive fiber mats, crosslinking was accomplished by high-temperature curing for extended periods of time, which would likely denature incorporated growth factors or proteins [26, 25].

To design a broadly-useful polymer-nanoparticle composite, a photo-crosslinkable, thermoresponsive macromer was developed to allow for electrospinning and crosslinking at room temperature. NIR-absorbing AuNRs were incorporated into the precursor electrospinning solution, and electrospinning and UV-induced crosslinking yielded highly swellable fibrous mats that undergo rapid, reversible deswelling upon irradiation with an NIR laser. Initial trials show that the release of encapsulated proteins from the nanofiber-nanorod composite mats can be triggered by NIR irradiation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAm, Aldrich) was recrystallized from hexanes and polyethylene glycol acrylate (PEG-A; average Mn 375 Da, Aldrich) was passed through an inhibitor removal column prior to use. All other chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich (polyethylene oxide (PEO, MW ~900,000), acryloyl chloride, triethylamine, acrylamide, 2,2′-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated bovine serum albumin (FITC-BSA), HAuCl4•3H2O, NaBH4, AgNO3, L-ascorbic acid), Fisher Chemicals (ethyl ether, 1,4-dioxane, tetrahydrofuran (THF), dichloromethane (DCM)) or Fluka (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), PEG-SH (MW=5000)) and used as received. The photoinitiator Irgacure 2959 (I2959, Ciba) was dissolved into a stock solution of 0.5% w/v in deionized water for further use. Milli-Q (18Ω, Milli-Pore) water was used with all solutions in preparing AuNRs.

2.2. Synthesis of PNPA Macromer

Free radical copolymerization of 5.93 g NIPAm and 2.60 mL PEG-A (feed ratio 87:13) was carried out in 1,4-dioxane (5% w/v monomers to solvent) with 12.10 mg AIBN as a heat-activated radical initiator (1:810 ratio to total monomer). Monomers and initiator were added to 200 mL dioxane in a round-bottomed flask, which was subsequently sealed and purged with nitrogen gas for 15 min. The entire reaction was then heated to 65 °C and allowed to proceed for 12 h. After 12 h, polymerization was terminated by the addition of 4 mg of 4-methoxyphenol and the reaction was cooled to room temperature. The macromer poly(NIPAm-co-PEG) (PNP) was collected by concentration via rotoevaporation and then precipitation from hexanes. The recovered macromer was then twice redissolved in THF and precipitated from ethyl ether, and dried under vacuum for 12 h, yielding PNP as a white solid.

7.06 g PNP were dissolved in 200 mL DCM in an oven-dried three-neck round-bottomed flask fitted with an addition funnel filled with 50 mL additional DCM. The reaction was capped and placed on ice and purged with nitrogen gas for 20 min, following which 2.45 mL TEA were added to the PNP solution and 1.42 mg acryloyl chloride were added to the addition funnel via syringe. The acryloyl chloride solution (3% v/v) was added dropwise to the reaction over 30 min, and the reaction was maintained at low temperature for 4 h, yielding poly(NIPAm-co-PEG-A) (PNPA). The reaction was transferred to a single-necked flask, and DCM was partially removed by rotoevaporation, leaving a highly-concentrated macromer solution. To prevent PNPA from adhering to the sides of the flask, DCM was not completely removed. THF was added to this solution, causing most of the triethylammonium salt to precipitate, and the remaining DCM was removed by performing rotoevaporation at a temperature and pressure between the boiling points of DCM and THF. Following DCM removal, the solution was vacuum-filtered to remove TEA salts, and then was precipitated twice from ethyl ether. The resulting white solid was dried under vacuum for 12 hours, yielding 5.42 g PNPA that were stored at RT prior to use.

2.3. Synthesis of Gold Nanorods

AuNRs were synthesized using a seed-mediated growth method previously described in the literature [27]. A seed solution containing hydrochloroauric acid (HAuCl4), CTAB and sodium borohydride was added to a growth solution of HAuCl4, CTAB, ascorbic acid, and silver nitrate. AuNRs formed after several hours. The nanorods’ surface was then modified by drop-wise addition of mPEG-SH (MW=5000) [28].

2.4. NMR Characterization

NMR characterization was performed on a Bruker 360 MHz spectrometer operating at 300 K. Samples were recorded in deuterated DMSO, and the spectra were calibrated to the residual solvent peak (2.50 ppm).

2.5. UV-Vis Characterization

UV-Vis characterization was performed on a Tecan Infinite M200. Absorbance scans were performed with a 2 nm resolution from 300 nm to 1000 nm. Absorbance scans were performed in plastic cuvettes on a water-swollen, crosslinked PNPA mat for polymer absorbance readings and on an aqueous AuNR solution for AuNR absorbance measurements.

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Characterization

FT-IR characterization was performed on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 FT-IR Spectrometer. 16 scans for background and sample spectra were recorded for each sample with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Multi-polymer mats were scanned on two sides of the same scaffold.

2.7. Light Scattering

PNPA was dissolved in filtered deionized water at several concentrations between 0.25 mg/mL and 1.0 mg/mL, sonicated for 2h, filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE syringe filter and allowed to sit for 24h before the macromer molecular weight was determined by static light scattering. Measurements were performed in a Malvern Zetasizer ZS with a toluene standard, and weight-average molecular weight was calculated (along with the z-average radius of gyration Rg and second virial coefficient A2) according to the equation:

I(q, c) is the excess scattering intensity over solvent, c is the polymer concentration, q is the scattering vector

n is the solvent refractive index, λ = 532 nm is the wavelength of light, Θ = 173° is the scattering angle and K is the scattering constant equal to:

where NA is Avogadro’s number. The value chosen for dn/dc was 0.170, in accordance with reported literature values for multiple NIPAM-based copolymers [29, 30]. All calculations were performed by the instrument software. Dynamic light scattering measurements were obtained from samples at a concentration of 0.25 mg/ml.

2.8. Fabrication of Crosslinked Fibrous Scaffolds

Fibrous mats of PNPA either with or without AuNRs were formed via electrospinning. PEO was dissolved overnight prior to spinning at 4 wt% in deionized water, and PNPA was dissolved at either 20 wt% (without AuNRs) or 30 wt% (with AuNRs) in 0.5 wt% I2959 solution. The electrospinning solution was made by mixing PEO and 20% PNPA solution in a 1:1 ratio for scaffolds without AuNRs, and by mixing PEO, 30% PNPA solution and a 1.71×10−8 M solution of AuNRs in a 3:2:1 ratio, for a final solution concentration of 2% PEO and 10% PNPA both with and without nanorods. The solution was loaded into a 10-mL plastic syringe (Becton-Dickinson), which was fitted with an 18 gauge needle connected to a power supply and loaded into a syringe pump. Fibrous scaffolds were collected on a grounded rotating mandrel spinning at an angular velocity of 13.2 rad/sec. Scaffolds were formed with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/hr, a supplied voltage of 12–20 kV from a high-voltage power supply (Gamma High Voltage), and a distance of 9–15 cm from the collector. After electrospinning, the fibrous scaffold was removed from the collector for crosslinking. Sections of the scaffold were placed in a Petri dish in a sealable plastic cover, which was purged with nitrogen and sealed. The scaffolds were then exposed to 10 mW/cm2 365 nm collimated UV light (EXFO) for 30 min on each side to ensure complete crosslinking of the pendant vinyl groups on the PNPA macromer.

2.9. Swelling Ratio Measurements

Mass swelling ratios for bulk hydrogels were calculated by first forming bulk gels by exposing 10% w/v solutions of PNPA in I2959 solution to UV light, weighing the formed gels, and then equilibrating them in deionized water at varying temperatures. Initial equilibration at room temperature was performed for 24 h, and equilibration of gels at different temperatures was performed for 2 h. The swelling ratio was calculated as (Ws/Wd) where Ws is the weight of equilibrated gels and Wd is the macromer weight contribution to the weight of the gels. Mass swelling ratios for fibers were calculated analogously to those for bulk gels, and area swelling ratios for fibers were calculated as Aw/Ad where Aw is the area of the swollen scaffold and Ad is the area of the dry scaffold prior to immersion in water.

2.10. SEM and Backscatter

Fibers with and without AuNRs were distributed onto SEM plates and sputter coated. Fiber morphology was imaged using environmental scanning electron microscopy (FEI Quanta 600 ESEM), and backscatter micrographs were used to image nanorods within the fibers by virtue of the microspheres’ Z-contrast, where higher atomic numbers, Z, (i.e. gold) appeared as bright spots, a method previously employed by our group to image AuNRs in polymer composites [11].

2.11. Near-infrared (NIR) Laser Light Irradiation and Confocal Microscopy

Fibers with nanorods were swelled with an aqueous solution of FITC-BSA (1.0 mg/mL) to enable fluorescent imaging, and fiber morphology was visualized using an Axio Observer Z1 inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss). 1.5 micrometer slices were captured with a 63X objective and were reconstructed using LSM Image Browser (v4.2.0.121). An NIR laser (OEM Laser Systems, 808 nm, 1.1 W) was applied to the sample and images were taken before lasering, during lasering after 0.5 min, and after lasering for 1.0 min. Following 1.0 min of lasering, fibers were allowed to reswell for 3.0 min, at which time an image was taken to assess reswelling.

2.12. Fiber Diameter and Fiber Density Calculations

Fiber diameter was quantified for scaffolds in solution before, during, directly after, and 3 minutes after exposing samples to 808 nm laser light for 60 s. Confocal images were smoothed in ImageJ (NIH) before further calculation. To quantify fiber diameter, intensity profiles were taken in ImageJ across individual fibers, resulting in a Gaussian intensity distribution for each fiber. The full width at half-maximum intensity (FWHM) was calculated for each fiber using a custom MATLAB (Mathworks) script employing linear interpolation for intensity between pixels. Diameters were calculated for 20 fibers in each group, and statistical testing on the inter-group differences was performed by ANOVA and Bonferroni-Holm post-hoc tests using the Daniel’s XL Toolbox plugin for Microsoft Excel. Fiber density was calculated from the same confocal images, by taking horizontal intensity profiles at 10 different heights on each image. The number of fibers crossing each sampled intensity line was quantified by visual inspection of the intensity profile and corroboration with the raw confocal image. Daniel’s XL Toolbox in Excel was again used to perform ANOVA and Bonferroni-Holm post-hoc tests for significance.

2.13. NIR Transmittance Measurements

Samples with and without nanorods (+NR, −NR, respectively) were allowed to swell overnight in aqueous solution, after which they were exposed to 1.1 W NIR laser (OEM Laser Systems). Four cycles of 1.0 min laser ON and 4.0 min laser OFF were performed in triplicate to assess change in transmittance between fibers +NR and −NR. Transmittance values were recorded using a radiometer (OEM Laser Systems) every 5 seconds during laser exposure, and at 15 second intervals for the first 60 seconds after laser exposure.

2.14. Triggered Protein Release

Fiber samples of ~2.0 mg were allowed to swell in freshly-prepared 2.2 mg/mL FITC-BSA aqueous solution for one hour at 4 °C to allow for complete swelling of the network. Fibers were then transferred to fresh 4.0 mL Milli-Pore H2O (18.2Ω) for 30 minutes to wash FITC-BSA from the surface and equilibrate to room temperature, after which the samples were again transferred to fresh 2.0 mL of Milli-Pore H2O to begin the release study. One experimental set (+NR+Laser) and two control sample sets (+NR−Laser, −NR+Laser) were assessed. Lasered samples were incubated for three cycles of thirty minutes at room temperature (Laser OFF) followed by exposure to a 1.1 W NIR laser for 2.0 min (Laser ON), while non-lasered samples were incubated for the entirety of the experiment at room temperature. Aliquots at each time point were taken and stored at 4 °C. All sample sets were performed in triplicate. Each time point was assessed for FITC-BSA under fluorescence (excitation: 490 nm, emission: 525 nm) using a Tecan Infinite M200 (Männedorf, Switzerland). Release was normalized to the dry polymer weight of each sample.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Polymer and Bulk Gel Characterization

The PNPA macromer was prepared in a two-step reaction in order to first incorporate a hydrophilic co-monomer with NIPAm to increase the polymer LCST, and then to functionalize the random copolymer with photopolymerizable acrylates (figure 1a). The ratio of total PEG to NIPAm repeat units in the final macromer was calculated by integration of 1H NMR peaks and found to be 6.7:93.3, with 44.6% of the PEG units functionalized with a pendant acrylate group (figure 1b). The final ratio of PEG to NIPAm is significantly lower than the feed ratio—likely due to different reactivities of the two monomers—but the ratio could be easily tuned by adjusting the relative quantities of monomers in the first synthesis step. Using light scattering, the polymers were determined to have a number average size of 8.17 nm with a standard deviation of 30.1%, leading to calculation of an average molecular weight of the copolymer to be 49.9 kDa.

Figure 1.

(a) Synthesis of PNPA macromer. (b) 1H NMR spectrum of PNPA used for determining chemical composition.

We next characterized the properties of bulk gels of the PNPA polymer. The relatively low acrylate modification of the polymer (3.0 % of total repeat units) was still sufficient to enable rapid crosslinking within minutes of UV exposure. To probe the thermal responsiveness of PNPA gels, we measured the polymer swelling ratio at various temperatures from 20 to 45 °C (figure 2). Gels remained highly swollen up to approximately 30 °C, and then due to the hydrophilic to hydrophobic thermal transition, the swelling ratio dropped to nearly 1 between 30 and 40 °C. Based on this data, it is clear that the LCST of our specific formulation appears to be ~35 °C, which is higher than what is observed for pure poly(NIPAm), likely due to the incorporation of hydrophilic PEG. The exact temperature at which the LCST occurs could be tuned in an application-specific manner by varying the quantity of PEG incorporated in the first synthesis step, while acrylate density can be independently controlled with the stoichiometry of the second step (figure 1a) to maintain a specific crosslink density in PNPA hydrogels. Importantly, through incorporation of slightly more PEG-A, it should be possible to tune the final macromer to exhibit an LCST above 37 °C, to allow deswelling to be triggered in cell culture or in vivo.

Figure 2.

Mass swelling ratio of PNPA bulk polymer gels measured as a function of temperature.

3.2 Electrospun Fiber Characterization

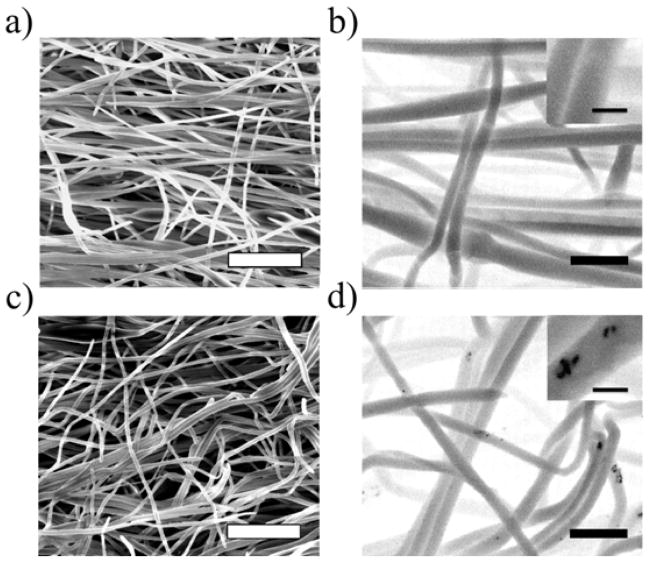

PNPA and initiator were successfully electrospun from an aqueous solution into fibrous scaffolds using PEO as a carrier polymer to increase the viscosity of the spinning solution. The use of water as a solvent for electrospinning is beneficial for biological applications. It removes the risk of trapping small amounts of organic solvent in the fiber mat, and the mild spinning conditions allow encapsulated proteins to maintain their functionality. SEM micrographs were taken of the PNPA mats spun with and without AuNRs (figure 3a, c), and show that fibers are largely distinct and free of beads, which have been common occurrences in past studies of electrospun NIPAm derivatives [32, 33]. The average diameters of dry fibers with and without AuNRs are 298 ± 61.2 nm and 308 ± 59.9 nm, respectively, and the incorporation of AuNRs (31.1±4.5 nm by 9.2±2.8 nm, length and width, respectively) does not appear to affect the morphology of electrospun fibers. Because AuNRs are much smaller than the fiber diameter and preserve fiber morphology, they can be directly added to the spinning solution, which simplifies the processing of the composite scaffold. To verify that nanorods added to the spinning solution are in fact encapsulated within fibers during electrospinning, backscatter micrographs were captured of fibers with and without AuNRs (figure 3b, d). It can be seen that AuNRs are pulled inside of individual fibers during electrospinning, and that they are diffuse across the entire mat. While mini-aggregates of nanorods can be seen in the backscatter images (figure 3d, inset), these are few in number and the PEGylation of the nanorods prevents them from aggregating so closely that their absorbance peak is shifted.

Figure 3.

SEM images of fibers (a) without and (c) with NRs (scale bars = 5 μm); Backscatter images of fibers (b) without and (d) with NRs (scale bars = 1 μm; inset scale bars = 200 nm).

The sensitivity of the PNPA/AuNR fibrous nanocomposites to NIR light is contingent upon NIR penetration into the water-swollen fibrous mats and recapitulation of the thermoresponsive character of PNPA in fiber form. PNPA fibrous gels exhibit negligible absorbance of light across the UV/visible/NIR spectrum including at the NIR laser wavelength of 808 nm (figure 4a). This minimal absorbance allows the laser to penetrate the composite scaffold and excite encapsulated AuNRs, which absorb strongly in the NIR. Exploring the thermal behavior of the fibrous gels, we found that similar to bulk gels, fibrous mats exhibit distinct deswelling around the LCST of the polymer, turning opaque and shrinking to ~25.0% of their maximum area, from 2.96 ± 0.143 times dry area to 0.74 ± 0.052 times (figure 4b). It is particularly interesting to note that at higher temperatures, the area of the fibrous gels is less than that of dry scaffolds, behavior that was not observed for the bulk polymer.

Figure 4.

(a) Absorbance of AuNRs and crosslinked PNPA fibrous gels with wavelengths used for crosslinking and AuNR NIR excitation highlighted by the arrows. (b) Areal swelling ratio of crosslinked fibrous PNPA scaffold as a function of temperature.

3.3 NIR-Induced LCST Transition in Fibrous Scaffolds

Successful incorporation of AuNRs into fibrous mats of PNPA allows us to explore if NIR irradiation triggers the collapse of these scaffolds. We first characterized the rate and reversibility of the thermal transition in response to NIR stimulation by monitoring the opacity of PNPA fibrous mats with and without AuNRs (figure 5). Composite fibers containing AuNRs exhibited a marked decrease in transmittance upon irradiation due to the increased opacity of the mat above its LCST, as well as an increase in nanorod concentration. The fiber mat rapidly relaxes upon removal of the NIR stimulus, with nearly complete recovery after 1 min and complete recovery at 4 min. Additionally, this behavior is repeatable, with multiple cycles of deswelling and reswelling possible in a short period of time. Fiber mats lacking AuNRs do exhibit a small decrease in transmittance upon irradiation, likely caused by background absorption of NIR light by the polymer and aqueous surroundings resulting in a slight increase the surface temperature of the mats. The change in transmittance, between 2 and 60 seconds of laser exposure is only 0.042 ± 0.0041 for scaffolds without NRs, compared to 0.579 ± 0.035 for scaffolds with nanorods. The absorption of NIR light by the AuNRs is also evident in the transmittance profiles; baseline values for nanocomposite transmittance (0.912 ± 0.029) are lower than those for pure polymer (0.972 ± 0.011) due to the inherent absorption of some NIR light by the encapsulated nanorods.

Figure 5.

Transmittance of 808 nm NIR light through water-swollen PNPA fiber mats across four cycles of 1 min NIR laser exposure and 4 min relaxation with (+NR) and without (−NR) AuNRs.

We next probed the macroscopic appearance of swollen fiber mats during NIR irradiation (figure 6a). Rapid collapse of the gel is readily observed within 1 minute of irradiation, with complete re-swelling upon removal of the stimulus within a few minutes. Furthermore, the focused nature of the laser beam allows the collapse to be spatially resolved, as regions without direct exposure to the laser do not undergo deswelling (not shown). While macroscopic deswelling is readily apparent during NIR exposure, whether the collapse was mediated by the drawing together of the fibers in the mat, or by deswelling of individual fibers, with each one acting like an individual hydrogel undergoing a volume phase transition was unclear. To probe the mechanism of deswelling, we used confocal microscopy to image fibers swollen with FITC-BSA while simultaneously irradiating with the laser (figure 6b). Interestingly, we found that both processes for deswelling occur simultaneously. The diameter of individual swollen fibers dropped from 1332 ± 192.8 nm before laser exposure to 868.9 ± 168.4 nm (mean ± s.d.) during laser exposure, and the rapid nature of fiber recovery is evident in the 1003 ± 114.1 nm fiber diameter observed immediately after switching off the laser, with almost full recovery after 3 min (figure 6c). The spacing between fibers (calculated at one specific orientation) also shrinks reversibly upon laser exposure (figure 6d), from 209.5 ± 26.34 fibers/mm when fully swollen to 451.2 ± 25.65 fibers/mm upon irradiation. The onset of water re-infiltration into the inter-fiber space was observed to be slightly less rapid than individual fiber re-swelling, as measured by imaging directly after removing the laser, but again almost complete re-swelling was observed after 3 min.

Figure 6.

(a) Macroscopic and (b) confocal microscopic images of AuNR-containing fibers at 0 (Before), 0.5 (During), and after 1.0 min laser exposure (After), as well as 3 min after laser treatment (Reswelled), demonstrating successful collapse and reswelling (scale bars = 2 mm and 20 μm, respectively). (c) Average diameter and (d) spatial density of PNPA fibers containing AuNRs before, during (after 0.5 min), and after 1.0 min NIR laser exposure, and after 3.0 min of reswelling. #Indicates statistical difference between each other (p < 0.01) and from unmarked groups (p < 0.001). *Indicates statistical difference from unmarked groups (p < 10−13).

3.4 NIR-Triggered Release from Fibrous Scaffolds

While AuNRs have been shown to incorporate into PNPA fibers and trigger reversible heating and fiber collapse upon laser irradiation, we aimed to demonstrate the application of this stimulus-responsiveness in molecule delivery. Proteins such as growth factors can be incorporated into nanofibrous mats and released in functional form [34], suggesting that the triggered collapse of nanofiber composites can be exploited to selectively trigger protein release from these scaffolds using NIR light (figure 7). To explore if NIR light could be used to induce release in our PNPA fiber system, fluorescent FITC-BSA was swollen into crosslinked fibrous mats, and release profiles were monitored with and without laser exposure (figure 8a). Following an initial burst release mediated by passive diffusion of protein adsorbed to or near the fiber surface, fibers were exposed to several cycles of 2.0 min NIR exposure (1.1 Watt) and demonstrated repeatable, reversible increases in release dependent on AuNR loading and subsequent laser exposure (figure 8b). For AuNR-loaded fibers exposed to the laser, the average release rate was 0.463 ± 0.227 μg FITC-BSA/mg polymer/min during laser exposure, and only 0.038 ± 0.052 μg FITC-BSA/mg polymer/min during periods of no exposure. The incorporation of AuNRs slightly increased the passive protein release rate compared to pure polymer, but this basal rate of release can be controlled in a facile manner by altering the acrylate density during synthesis of the macromer. The ability to trigger release of proteins from a fibrous scaffold may be useful for tissue engineering applications, where the spatial localization of release can be used to pattern a response or to deliver multiple doses of protein by irradiating select regions of a mat.

Figure 7.

Schematic of proposed release mechanism. (a) Irradiation causes local changes in fiber mats due to transition through LCST. (b) Top view and (c) cartoon cross-section of fibers: NIR irradiation collapses and draws together individual fibers, and encapsulated proteins (green circles) are released as fibers expel water. AuNRs (purple bars) are larger and remain within the fibers. The transition is reversible and repeatable.

Figure 8.

(a) FITC-BSA cumulative release (μg FITC-BSA per mg polymer) and (b) release rate (μg FITC-BSA per mg polymer per minute) from swollen fibrous mats with (+NR) and without (−NR) AuNRs. All samples were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, and lasered samples (+Laser) were then exposed to 2.0 min of 1.1W NIR light (808nm). Three cycles of 30 minutes without lasering (Laser OFF) and 2.0 min with lasering (Laser ON) were performed, while non-lasered (no Laser) samples were incubated for the same time (32 minutes per cycle) at room temperature. All groups were performed in triplicate and amount released was normalized to initial dry polymer weight. * Significantly different (p < 0.05) from other group in ON part of cycle, # Significantly different (p < 0.05) from same samples in OFF part of cycle.

4. Conclusions

We have shown that AuNRs can be stably incorporated into nanofibrous mats constructed by crosslinking an acrylate-bearing thermoresponsive macromer after electrospinning. These fibrous nanocomposites exhibited reversible collapse upon irradiation with NIR light, which was mediated by both fiber aggregation and individual fiber deswelling, and was spatially localized to the region of direct NIR exposure. Irradiation of the nanocomposite system has been demonstrated as a trigger for the release of encapsulated protein, but the composite may be useful in other applications as well. For example, multi-polymer fiber mats could be formed by spinning PNPA/AuNR fibers jointly with another photo-crosslinkable macromer, which could allow the PNPA to release encapsulated factors on demand while another material presents mechanical or biochemical cues to cells on a tissue engineering construct. Alternatively, a nanocomposite fiber mat could be used as a membrane covering for a microfluidic drug reservoir, allowing molecules to be released when NIR irradiation contracts the membrane to form mesoscopic pores. The proof of concept demonstrated here is a useful first step to developing functional, ‘smart’ nanofibrous scaffolds with a facile method of manipulation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant AR056624) and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (JSK). We thank Iris Kim for assistance with ESEM and backscatter imaging, and Dr. Harini Sundararaghavan for assistance with confocal microscopy.

References

- 1.Mano JF. Advanced Engineering Materials. 2008;10:515–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shibayama M, Suetoh Y, Nomura S. Macromolecules. 1996;29:6966–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan TT, Zhang YJ, Guan Y. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:1410–5. doi: 10.1021/bm900022m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang XF, Zhou L, Zhang X, Dai H. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2010;116:1099–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sershen SR, Westcott SL, Halas NJ, West JL. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2000;51:293–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<293::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bikram M, Gobin AM, Whitmire RE, West JL. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;123:219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu CY, Guo J, Yang WL, Hu JH, Wang CC, Fu SK. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2009;19:4764–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu HX, Wang CY, Gao QX, Liu XX, Tong Z. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6:275–81. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charati MB, Lee I, Hribar KC, Burdick JA. Small. 2010;6:1608–11. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hribar KC, Metter RB, Ifkovits JL, Troxler T, Burdick JA. Small. 2009;5:1830–4. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hribar KC, Lee MH, Lee D, Burdick JA. ACS Nano. 2011;5:2948–56. doi: 10.1021/nn103575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissleder R. Nature Biotechnology. 2001;19:316–7. doi: 10.1038/86684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei QS, Ji J, Shen JC. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2008;29:645–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sill TJ, von Recum HA. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1989–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chew SY, Wen J, Yim EKF, Leong KW. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2017–24. doi: 10.1021/bm0501149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loh XJ, Peh P, Liao S, Sng C, Li J. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;143:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thakur RA, Florek CA, Kohn J, Michniak BB. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2008;364:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng J, Aigner A, Czubayko F, Kissel T, Wendorff JH, Greiner A. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:1484–8. doi: 10.1021/bm0492576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanders EH, Kloefkorn R, Bowlin GL, Simpson DG, Wnek GE. Macromolecules. 2003;36:3803–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu XL, Zhuang XL, Chen XS, Wang XR, Yang LX, Jing XB. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2006;27:1637–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi JS, Lee SJ, Christ GJ, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ifkovits JL, Wu K, Mauck RL, Burdick JA. Plos One. 2010:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker BM, Gee AO, Metter RB, Nathan AS, Marklein RA, Burdick JA, Mauck RL. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker BM, Nerurkar NL, Burdick JA, Elliott DM, Mauck RL. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:101012. doi: 10.1115/1.3192140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Sutti A, Wang XG, Lin T. Soft Matter. 2011;7:4364–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal AK, Jassal M, Vishnoi A, Save NS. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2005;95:681–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sau TK, Murphy CJ. Langmuir. 2004;20:6414–20. doi: 10.1021/la049463z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao HW, Hafner JH. Chemistry of Materials. 2005;17:4636–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao J, Wu C. Macromolecules. 1997;30:6873–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo SZ, Hu XL, Zhang YY, Ling CX, Liu X, Chen SS. Polymer Journal. 2011;43:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdick JA, Prestwich GD. Advanced Materials. 2011;23:H41–H56. doi: 10.1002/adma.201003963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu SY, Wang ZM, Li JB, Ren J. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering. 2010;295:32–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rockwood DN, Chase DB, Akins RE, Rabolt JF. Polymer. 2008;49:4025–32. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim TG, Lee DS, Park TG. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2007;338:276–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haxaire K, Marechal Y, Milas M, Rinaudo A. Biopolymers. 2003;72:10–20. doi: 10.1002/bip.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]