Abstract

Objectives

Older adults with macular disease are at increased risk of memory decline and incident dementia. Low vision rehabilitation (LVR) aims to preserve independence in people with irreversible vision loss, but comorbid memory problems could limit the success of rehabilitation. This study examined whether performance on a brief memory test is related to functional outcomes among older patients undergoing LVR for macular disease.

Design

Observational cohort study of patients receiving outpatient LVR

Setting

Academic center

Participants

91 seniors (average age 80.1 years) with macular disease

Measurements

Memory was assessed at baseline with a 10-word list; memory deficit was defined as immediate recall of ≤ two words. Vision-related function was measured with the 25-item Visual Function Questionnaire (VFQ-25)administered at baseline and during subsequent interviews (mean length of follow up = 115 days). Linear mixed models (LMMs) were constructed to compare average trajectories of four VFQ-25 subscales: near activities, distance activities, dependency, and role difficulty.

Results

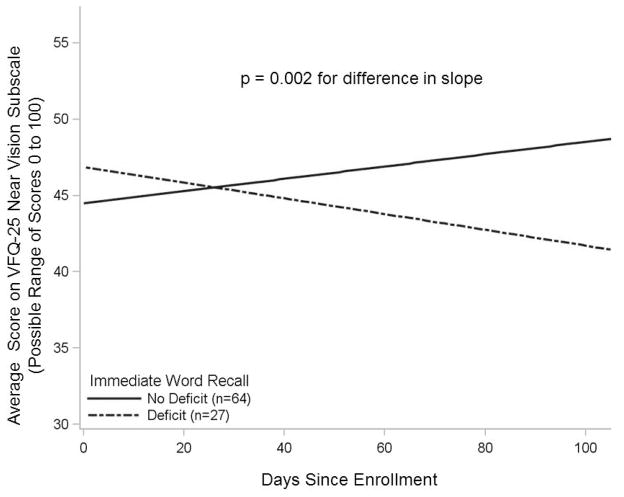

The 29.7% of patients with memory deficit tended to decline in ability to accomplish activities that involve near vision. Controlling for age, sex, and education, the functional trajectory of participants with memory deficit differed significantly from that of participants with better memory (p=0.002), who tended to report improvements in ability to accomplish near activities.

Conclusion

Among older adults receiving LVR for macular disease, those with memory deficit experienced worse functional trajectories in their ability to perform specific visually mediated tasks. A brief memory screen may help explain variability in rehabilitation outcomes and identify patients who might require special accommodations.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, comorbidity, disability, cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive impairment is more prevalent and more rapidly progressive in older adults with vision impairment1–3, and approximately 4% of community dwelling older adults experience both impairments4. In particular, age-related macular degeneration (AMD) has been associated with two-fold increased risk of cognitive decline and incident dementia5, 6, and recent studies suggest that macular disease patients tend to perform poorly on tests of memory 1, 7. This epidemiologic link between vision impairment and cognitive impairment is significant, in part, because comorbid cognitive impairment further increases a visually impaired older adult’s risk of disability4.

The functional consequences of vision loss are often addressed by referral to low vision rehabilitation (LVR). LVR is a multi-disciplinary service that incorporates the expertise of optometrists, occupational therapists, orientation and mobility specialists, and assistive technology (AT) specialists to promote independence among visually impaired individuals by equipping them with tools and training to accomplish specific visually mediated tasks8. However, if the patient’s ability to learn new techniques and adapt to new equipment is affected by comorbid memory problems, the benefits of LVR may be decreased.

Qualitative research has uncovered unmet needs among LVR patients with comorbid deficits in vision and cognition, and LVR providers expressed uncertainty about how to accommodate patients with memory problems9. Participants with memory problems may experience different outcomes in LVR either because they are less able to engage in training, or because services are rendered to them at a different pace or manner. The randomized, controlled LOVIT trial demonstrated effectiveness of outpatient LVR in preserving vision-related function, but LOVIT excluded individuals who screened positive for cognitive impairment10. Thus, the trial did not address whether cognitive deficits (such as memory problems) are associated with LVR outcomes.

This study aims to examine the association between memory deficit and functional outcomes in older adults receiving LVR. The specific objective is to determine whether performance on a simple memory test at baseline relates to longitudinal trajectories of visual function scores among older macular disease patients enrolled in an outpatient LVR program.

METHODS

Population and Setting

Recruited patients were aged 65 years or older with macular disease and initiating LVR in the Duke LVR Clinic between September 2007 and March 2008. Recruitment occurred on specific days during the study period; on recruitment days, all consecutive eligible patients were invited to participate. Of 139 invited patients, 103 (74.1%) signed consent forms and 101 completed memory testing at baseline. Those who declined did not differ significantly from study participants by sex, race, or age. Ten subjects lacked longitudinal functional data (mean age 80.6 ± 6.3 years, 9 female, 10 white, 3 with memory deficit). The remaining 91 subjects were included in this analysis. The study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

The Duke LVR Clinic coordinates a multi-disciplinary outpatient rehabilitation service within the Duke Eye Center. The LVR team is led by an optometrist and includes an AT specialist, an occupational therapist, and a low vision technician. New patients receive a standardized assessment and then, as is typical in LVR8, providers develop an individualized rehabilitation plan, based on participant needs and personal goals. Services may be delivered in the clinic or the patient’s home. Typical interventions include refraction, provision of and training for vision assistive equipment (VAE), or educational interventions such as preferred retinal locus (PRL) training or information about lighting. Over time, rehabilitation plans may be refined to suit a participant’s changing goals or needs.

Data Collection

Data were collected in person at baseline and during as many as three subsequent telephone interviews, with interviews separated by at least 30 days. Three follow-up interviews were completed by 86 of 91 (94.5%) study participants. The amount of time between interviews varied due to participant availability, such that follow-up periods ranged from 32 to 297 days (mean 115 ± 29 days). Data were collected by investigators who were not involved in the clinical care of the patients; the rehabilitation team was masked to data collected during the study.

Memory Testing

Cognitive testing was completed on the day of enrollment, in private exam rooms by individuals trained and supervised by a neuropsychologist to administer cognitive tests according to standardized instructions. The cognitive battery included several tests of memory, including immediate and delayed recall of a 10-item word list from the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status – modified (TICS-m) 11, 12 and Logical Memory tests of prose recall13. All memory scores were highly correlated with each other. In order to examine the most easily reproducible measure, memory deficit was defined as the lowest quartile of scores on the immediate recall task from the TICS-m. In this test, a list of ten words is read aloud and subjects are asked to recall as many words as possible immediately after hearing the list. The scores approximated a normal distribution (mean 3.5 ± 1.6, median and mode = 3, range = 0 to 8). Participants with memory deficit recalled two or fewer words.

Visual Function Tests

Vision-dependent function was assessed with the Version 2000 National Eye Institute Vision Function Questionnaire – 25 (VFQ-25), a well-validated tool for measuring the influence of visual symptoms on generic health domains and tasks of daily living14. The VFQ-25 was administered aloud to participants at baseline (in person) and during follow-up telephone interviews. Individual items from the VFQ-25 can be combined to derive 11 subscales that reflect the impact of impaired vision on specific domains of health, including activity-related function and psychological well-being. Possible scores on each scale are 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function.

Four VFQ-25 subscales were evaluated in this study: near activities, distance activities, role difficulties, and dependency15. The near activities and distance activities subscales were selected because items in these subscales are particularly sensitive to change through outpatient LVR16. The role difficulties and dependency subscales were selected because earlier work suggested that the presence of comorbid memory impairment is associated with greater dependency among visually impaired older adults4, 9.

The near activities score is based on responses to questions that assess how much difficulty participants have, as a result of their vision, with reading, cooking, sewing, fixing small things, or finding something on a crowded shelf. The distance activities score is based on responses to similar questions about difficulty seeing movies, plays, sporting events, and reading street signs or store names while riding along in a car. Participants can choose among responses indicating “no difficulty,” “a little difficulty,” “moderate difficulty,” “extreme difficulty,” “stopped doing the activity because of eyesight,” or “stopped doing the activity for other reasons.” The role difficulty score is based on participant response to the questions, “Do you accomplish less than you would like because of your vision?” and “Are you limited in how long you can work or do other activities because of your vision?” Participants choose between responses “[all, most, some, a little, none of] the time.” The dependency score is derived from participant response to the following statements: “I stay home most of the time because of my eyesight;” “Because of my eyesight, I have to rely too much on what other people tell me;” and “I need a lot of help from others because of my eyesight.” Participants indicate whether they believe these statements are “definitely true,” “mostly true,” “not sure,” “mostly false,” or “definitely false.”

Other Variables Collected

Information on demographics, living status, and physician-diagnosed medical conditions was collected in the baseline interview. The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was administered to each participant at baseline17. Information related to ophthalmologic medical history and visual acuity measures were abstracted from the Duke Eye Center chart by a certified ophthalmologic assistant using a standardized case report form.

Analysis

Linear mixed models (LMMs) were constructed to assess whether visual function outcomes differed over time among participants with memory deficit at baseline. LMMs are an appropriate method to compare differences in the longitudinal data from this study for several reasons. First, the time that elapsed between telephone interviews varied between participants. LMMs model rates of change in an outcome, which can be determined from two or more data points regardless of the amount of intervening time. Thus, mixed models are useful when there is high variability in participants’ length of follow-up and timing of repeated measurements. Second, mixed models appropriately handle observations that are not independent, such as repeated measurements of function. Finally, function is a dynamic variable and transient declines in function are common in old age and do not always reflect long-term functional trajectories18. Thus, it may be more appropriate to consider participants’ averaged functional trajectories, utilizing all available data on each participant, rather than relying on “change in function” between two arbitrary time points.

Tests of significance were conducted in models that included sex, age, education level, memory group (deficit or no deficit), time, and a memory group by time interaction term. The primary test of interest was whether the memory group by time interaction term was significant, because this test indicates whether the average functional trajectories are the same over time for participants with and without a memory deficit. A graphical representation of this relationship was obtained by displaying population lines calculated using parameter estimates from models that contained only memory group, time and the interaction term. Analyses were conducted with SAS software version 9.2 (Cary, NC); p value ≤ 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the cohort. Most participants were white, with the most common macular condition being AMD, which has a predilection for Caucasians. Persons with memory deficit tended to be older, less educated, more likely male, less often married and to endorse more comorbid medical diagnoses. A higher proportion of people with memory deficit had dry, as opposed to wet, AMD and a lower proportion had received intra-ocular treatment with steroids, laser, or anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Cohort

| Baseline Characteristics | Overall Cohort N=91 | Participants with Memory Deficita N=27 | Participants without Memory Deficit N=64 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in Years, Mean (SDb) | 80.1 (8.0) | 84.1 (7.6) | 78.4 (7.6) |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female, N(%) | 58 (63.7) | 15 (55.6) | 43 (67.2) |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Caucasian, N(%) | 87 (95.6) | 26 (96.3) | 61 (95.3) |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| ≤ High School, N(%) | 31 (34.1) | 12 (44.4) | 19 (29.7) |

| College, N(%) | 42 (46.2) | 11 (40.7) | 31 (48.4) |

| Beyond College, N(%) | 18 (19.8) | 4 (14.8) | 14 (21.9) |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | |||

| Married, N (%) | 42 (46.2) | 6 (22.2) | 36 (56.3) |

|

| |||

| Depression | |||

| % GDSc score ≥ 5 | 24 (26.4) | 8 (29.6) | 16 (25.0) |

|

| |||

| No. of 14 Comorbid Conditions Endorsedd | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.6) | 3.2 (1.7) | 2.5 (1.5) |

|

| |||

| TICS-mScoree Mean (SD) | 31.1 (5.1) | 27.1 (5.4) | 32.8 (3.9) |

| Min, Max | 7.0, 44.0 | 7.0, 35.0 | 25.0, 44.0 |

|

| |||

| Best Corrected Visual Acuity (ETDRSf) in Better Eye | |||

| Median | 20/50 | 20/50 | 20/50 |

| Interquartile Range | 20/40 to 20/100 | 20/50 to 20/100 | 20/40 to 20/100 |

|

| |||

| Type of Macular Disease | |||

| Wet AMDg, N(%) | 48 (52.7) | 11 (40.7) | 37 (57.8) |

| Dry AMD, N (%) | 18 (19.8) | 7 (25.9) | 11 (17.2) |

| Diabetic Macular Edema, N(%) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (3.7) | 0 |

| Epiretinal Membrane, N(%) | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 2 (3.1) |

| Otherh, N(%) | 17 (18.7) | 5 (18.5) | 12 (18.8) |

|

| |||

| History of Treatment with Intra-ocular Steroids, Laser, or anti-VEG-Fi | |||

| Agents, N(%) | 48 (52.8) | 10 (37.0) | 38 (59.4) |

|

| |||

| VFQ-25j Near Activities Score, Mean (SD) | 45.3 (24.4) | 47.5 (22.3) | 44.5 (25.3) |

|

| |||

| VFQ-25 Distance Activities Score, Mean (SD) | 49.6 (29.1) | 44.7 (32.0) | 51.6 (27.8) |

|

| |||

| VFQ-25 Dependency Score, Mean (SD) | 62.8 (29.3) | 61.6 (26.5) | 63.3 (30.6) |

|

| |||

| VFQ-25 Role Difficulty Score, Mean (SD) | 56.7 (28.0) | 52.4 (26.5) | 58.5 (28.6) |

Memory deficit was defined as present in participants who recalled ≤ two words from a 10-item word list during the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status, modified (TICS-m) Immediate Word Recall task.

SD = standard deviation

Depression defined as geriatric depression screen (GDS) score ≥ 517

Participants were asked whether a physician had ever diagnosed them with the following conditions: coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, arthritis, pulmonary disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, liver disease, kidney disease, cancer, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, hip fractures, ulcers

Global cognitive status was assessed with the modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status, which has a possible score range 0 to 50. A TICS-m score ≤ 27 is considered a positive screen for cognitive impairment.12

ETDRS = Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

AMD = age-related macular degeneration

Other primary macular diagnoses included: non-diabetic macular edema, branch retinal vein occlusion, choroidal neovascularization of the macula, pigment epithelial detachment, Stargardt’s Disease, Wagner’s Syndrome, myopic macular degeneration, presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, cone degeneration

VEG-F = vascular endothelial growth factor

VFQ-25 = 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire

Memory Deficit as a Predictor of Activities that Require Near or Distance Vision

In models adjusted for age, sex, and education, individuals who had memory deficit experienced significantly worse trajectories on the near vision activities subscale (p = 0.002). On average, these individuals’ VFQ-25 near vision subscale scores declined over time, whereas their peers with intact memory reported modest improvements in near vision activities (Figure 1). The numbers in Table 2 are derived from the linear mixed model that was fitted to this study’s data. Table 2 reports the VFQ-25 near vision activity subscale scores calculated for average study participants, with and without memory deficit, at 30 days, 60 days, and 90 days after beginning the LVR program.

Figure 1.

Low Vision Rehabilitation Participants with Memory Deficit Experienced Worse Functional Trajectories in Activities that Require Near Vision

In this observational study of 91 older adults with macular disease who were enrolled in outpatient low vision rehabilitation, visual function was assessed at baseline and during one to three follow-up interviews using the National Eye Institute Vision Function Questionnaire (VFQ-25). The near vision activities subscale of the VFQ-25 is based on participant response to questions that assess vision-related difficulty with reading, cooking, sewing, fixing small things, or finding something on a crowded shelf15. The data were used to construct linear mixed models to estimate average scores over time for participants with and without memory deficit. Memory was tested at baseline with a 10-item word list; memory deficit was present in participants who recalled ≤ 2 words immediately after the list was read aloud. Controlling for age, sex, and education level, VFQ-25 near vision activities subscale trajectories were worse among participants with memory deficit, compared to participants without memory deficit (p value 0.002, indicating a difference between groups in the rate of change of the VFQ-25 subscale over time). The VFQ-25 has a possible range of scores from 0 to 100; a 4- to 6-point change in VFQ-25 subscale scores is considered clinically significant19, 20.

Table 2.

VFQ-25 Near Activities Subscale Scores Calculated at 30, 60, and 90 days Post-enrollment in Low Vision Rehabilitation

| Memory Status | VFQ-25 Near Activities Subscale Scores (Range 0 to 100)* (95% Confidence Interval)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Days After Enrollment in LVR

| |||

| 30 days | 60 days | 90 days | |

| No Memory Deficit at Baseline | 45.5 (38.9 to 52.1) | 46.8 (40.3 to 53.3) | 48.0 (41.4 to 54.6) |

| Memory Deficit at Baseline | 41.5 (30.9 to 52.1) | 39.9 (29.4 to 50.4) | 38.4 (27.8 to 49.0) |

where y = VFQ-25 near activities score; m = 1 if memory deficit, 0 if no memory deficit; g = 1 if female, 0 if male; a = age in years; e = years of education; t = days since enrollment

To calculate the values in this table, we assumed average values of age, gender, and education within the study population: 80 years old, female, 14 years of education. We estimated such a patient’s VFQ-25 score at 30, 60, and 90 days following enrollment if she did, or did not, present with memory deficit.

The distance activities subscale scores did not change significantly over time and trajectories did not differ significantly among participants with or without memory deficit.

Memory Deficit as a Predictor of Role Difficulty or Dependency

In models adjusted for age, sex, and education, participants with memory deficit did not differ significantly from the rest of the cohort in their trajectories of the VFQ-25 role difficulty or dependency subscales. Overall, participants perceived an increasing level of difficulty with role performance, whereas VFQ-25 dependency scores did not change significantly over the study period.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of older patients receiving LVR for macular disease, memory deficit at baseline was associated with worse longitudinal outcomes related to specific tasks that require near vision. A 4- to 6-point change in VFQ-25 subscale score is considered clinically significant19, 20; thus, the functional trajectories observed in this study represent a meaningful difference in visual function between participants with and without memory problems. Consistent with some previous studies of treatment outcomes in LVR10, 16, participants with intact memory tended to report improvements in their ability to perform certain visually mediated tasks. However, this study is the first to demonstrate that older LVR patients with comorbid memory deficits may not experience similar gains in functional ability. This finding is significant, particularly in light of the frequent co-occurrence of memory problems in macular disease patients5, 6 and a previous observation that memory deficits are common among seniors receiving outpatient LVR1. Future research is needed to determine whether the functional outcomes of low vision patients with comorbid memory impairment might be improved by protocols to detect and accommodate this common comorbidity.

Efforts to promote independence in the face of vision loss – or any chronic condition - could be hindered by comorbid memory deficit. Yet cognitive evaluation is not routinely performed in many subspecialty services, including low vision rehabilitation. While this may be due in part to time constraints or to lack of personnel trained to administer cognitive tests, the current study found that a simple, fast memory screen (10-item word recall) distinguished individuals at risk for worse functional outcomes.

Although this study demonstrates a significant association between memory performance at baseline and subsequent functional trajectories in LVR, it does not determine why people with memory deficits experienced worse functional outcomes. One possibility is that memory impaired participants do not gain as much benefit from similar rehabilitation interventions, compared to their peers with intact memory. Another possibility is that people with memory impairments tend to receive a different array of services or their care is delivered in a different manner. LVR, like many rehabilitation services, is intentionally individualized in an effort to meet participant’s unique goals and needs. The present study did not assess specific aspects of care delivery or receipt of services that may have contributed to the observed differences in functional outcomes. A third possibility is that the relationship between memory deficit and functional trajectory was influenced by potential confounders (e.g., risk factors for functional decline that were more common among persons with memory deficit). Nonetheless, the finding that a brief memory test identified participants at risk of worse functional outcomes suggests an opportunity for improved care. Future research should investigate factors that contribute to the association described here and whether functional outcomes for LVR patients with memory problems may be improved by targeted accommodations.

Several limitations may impact the interpretation of results. First, although participants with and without memory deficits had similar visual acuity at baseline, the study did not measure or control for visual acuity at later time points. The relatively short duration of the study period (115 ± 29 days) makes it less likely that changes in visual acuity contributed substantially to the differing functional trajectories. Second, the accuracy of self-reported functional outcomes could be influenced by memory impairment. Nevertheless, the finding that memory deficits were associated with differences in perceived vision-related function is itself clinically relevant. Third, the same study personnel administered baseline and follow-up questionnaires and thus were not masked to cognitive status; the use of standardized tools to assess patient-reported functional outcomes should reduce potential bias.

This study found that LVR patients with intact memory experienced improvement in ability to perform specific visually mediated tasks, whereas their peers with poor word recall reported declining function on the same tasks. Future work should focus on rehabilitation strategies that optimize independence and quality of life for patients with comorbid vision loss and memory impairment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging K23 AG032867 (Beeson Award), 5P30AG028716 (Duke Pepper Center), the Brookdale Foundation, the American Federation for Aging Research, the John A Hartford Foundation, and the Durham VA Geriatrics Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC).

Sponsor’s Role: The funding agencies had no role in the conduct of the research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts relevant to this research.

Author Contributions:

Study concept and design: HEW, DW, LLS, SWC, GGP, DA, EM, CFP, LL, DCS, HJC

Acquisition of subjects or data: HEW, DW, SWC, GGP, DA

Analysis and interpretation of data: HEW, DW, LLS, SWC, GGP, DA, EM, CFP, LL, DCS, HJC

Preparation of the manuscript: HEW, DW, LLS, SWC, GGP, DA, EM, CFP, LL, DCS, HJC

Meeting: Some results were presented at the American Geriatrics Society meeting (May 2011)

References

- 1.Whitson HE, Ansah D, Whitaker D, et al. Prevalence and patterns of comorbid cognitive impairment in low vision rehabilitation for macular disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin MY, Gutierrez PR, Stone KL, et al. Vision impairment and combined vision and hearing impairment predict cognitive and functional decline in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1996–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reyes-Ortiz CA, Kuo YF, DiNuzzo AR, et al. Near vision impairment predicts cognitive decline: Data from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitson HE, Cousins SW, Burchett BM, et al. The combined effect of visual impairment and cognitive impairment on disability in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:885–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klaver CC, Ott A, Hofman A, et al. Is age-related maculopathy associated with Alzheimer’s Disease? The Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:963–968. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Leiby BE, et al. Activity loss is associated with cognitive decline in age-related macular degeneration. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemons TE, Rankin MW, McBee WL. Cognitive impairment in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study: AREDS report no. 16. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:537–543. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owsley C, McGwin G, Jr, Lee PP, et al. Characteristics of low-vision rehabilitation services in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:681–689. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence V, Murray J, Ffytche D, et al. “Out of sight, out of mind”: A qualitative study of visual impairment and dementia from three perspectives. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:511–518. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209008424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stelmack JA, Tang XC, Reda DJ, et al. Outcomes of the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Intervention Trial (LOVIT) Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:608–617. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.5.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt JSM, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neurosychiatr Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1988;1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welsh K, Breitner JCS, Magruder-Habib KM. Detection of dementia in the elderly using telephone screening of cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behavioral Neurol. 1993;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Psychological Corporation. WAIS-III: WMS III: Technical Manual. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Pitts J, et al. Psychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ). NEI-VFQ Field Test Investigators. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1496–1504. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.11.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, et al. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1050–1058. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stelmack JA, Stelmack TR, Massof RW. Measuring low-vision rehabilitation outcomes with the NEI VFQ-25. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2859–2868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill TM, Allore HG, Hardy SE, et al. The dynamic nature of mobility disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suner IJ, Kokame GT, Yu E, et al. Responsiveness of NEI VFQ-25 to changes in visual acuity in neovascular AMD: Validation studies from two phase 3 clinical trials. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3629–3635. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evaluation of minimum clinically meaningful changes in scores on the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) SST Report Number 19. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:205–215. doi: 10.1080/09286580701502970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]