Abstract

Context:

The newest variation of the i-gel supraglottic airway is a pediatric version.

Aims:

This study was designed to investigate the usefulness of the size 2 i-gel compared with the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway (PLMA) and classic laryngeal mask airway (cLMA) of the same size in anesthetized, paralyzed children.

Settings and design:

A prospective, randomized, single-blinded study was conducted in a tertiary care teaching hospital.

Methods:

Ninety ASA grade I–II patients undergoing lower abdominal, inguinal and orthopedic surgery were included in this prospective study. The patients were randomly assigned to the i-gel, PLMA and cLMA groups (30 patients in each group). Size 2 supraglottic airway was inserted according to the assigned group. We assessed ease of insertion, hemodynamic data, oropharyngeal sealing pressure and postoperative complications.

Results:

There were no differences in the demographic and hemodynamic data among the three groups. The airway leak pressure of the i-gel group (27.1±2.6 cmH2O) was significantly higher than that of the PLMA group (22.73±1.2 cmH2O) and the cLMA group (23.63±2.3 cmH2O). The success rates for first attempt of insertion were similar among the three devices. There were no differences in the incidence of postoperative airway trauma, sore throat or hoarse cry in the three groups.

Conclusions:

Hemodynamic parameters, ease of insertion and postoperative complications were comparable among the i-gel, PLMA and cLMA groups, but airway sealing pressure was significantly higher in the i-gel group.

Keywords: Classic laryngeal mask airway, i-gel, pediatric patients, ProSeal laryngeal mask airway

INTRODUCTION

Various types of supraglottic devices are widely used for securing and maintaining a patent airway for surgery requiring general anesthesia in children. They provide a perilaryngeal seal with an inflatable cuff, and are an alternative to tracheal intubation.[1] The i-gel airway is a novel and innovative supraglottic airway device made of a medical grade thermoplastic elastomer (styrene ethylene butadiene styrene (SEBS)), which is soft, gel-like and transparent.[2] The latest advent of the i-gel airway are its pediatric versions, which are now available in four different sizes – 1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5 – on the basis of body weight.[3] There are very few studies comparing the size 2 i-gel with ProSeal laryngeal mask airway (PLMA) and classic laryngeal mask airway (cLMA) of the same size to assess their performance in anesthetised and artificially ventilated children.

The purpose of this study was to compare the pediatric i-gel airway with the PLMA and cLMA for ease of insertion, oropharyngeal sealing pressure (OSP) and ease of gastric tube placement. We also compared the hemodynamic effects and postoperative complications, including blood staining, sore throat and hoarse cry.

METHODS

After approval from the Hospital Ethics Committee, 90 patients were studied. A randomized prospective study was planned to compare size 2 i-gel (Intersurgical Ltd., Wokingham, Berkshire, UK) with PLMA and cLMA of the same size.

The children included in the study were 1–6 years of age, ASA physical status I–II, weighing 10–20 kg and posted for elective surgeries of less than 1 h duration in the supine position including lower abdominal (e.g., colostomy closure), inguinal (e.g., herniotomy, circumcision) and orthopedic procedures (e.g., upper and lower limb surgeries). The following were excluded from the study: (i) patients with upper respiratory tract symptoms, (ii) those at risk of gastroesophageal regurgitation and (iii) those with airway-related conditions such a trismus, limited mouth opening, trauma or mass. Ninety patients were equally randomized to one of the three groups (i-gel, PLMA and cLMA) of 30 each for airway management using a computer-generated randomization program.

Written informed consent was taken from the parents prior to intervention and a standardized protocol for anesthesia was maintained for all cases. All the children were kept nil per mouth as per standard guidelines. They were premedicated with 0.3 mg/kg of midazolam syrup 1 h prior to induction of anesthesia. Induction of anesthesia included sevoflurane in oxygen with standard monitors placed. Anesthesia was maintained with 1–2% sevoflurane and 60% nitrous oxide in oxygen.

Once an adequate depth of anesthesia was achieved, the supraglottic device was inserted by the standard technique recommended by the manufacturer (introducer for PLMA, single-finger technique for cLMA). We considered easy up-and-down movement of the lower jaw, no reaction to pressure applied to both angles of the mandible and end-tidal sevoflurane concentration (EtSev) of 2.5% to indicate the adequate depth of anesthesia for insertion of the device. The technique for placement of i-gel is reviewed on the Web site. Each device was inserted by an experienced anesthesiologist who had performed at least 50 size 2 cLMA or PLMA and 20 size 2 i-gel placements.

The ease of insertion was graded as very easy, easy or difficult by the attending anesthesiologist. The device was inserted with “sniffing” position. The following manoeuvres were included: (i) chin lift, (ii) jaw thrust, (iii) head extension and (iv) neck flexion. If the device could be inserted without any manipulation, it was graded as “very easy.” If there was only one manipulation required, it was called “easy” and any difficulty more than that was graded as “difficult.” The number of attempts was noted, and it was considered a failure if the insertion was not successful in three attempts. The patient was then excluded from the study, and either a different size of the same device was inserted or the child was intubated with an endotracheal tube.

The device was fixed from maxilla to maxilla, and the cuff was inflated in the PLMA and cLMA groups using a cuff pressure monitor (Mallinckrodt Medical, Germany) to achieve a pressure of 60 cm H2O. This pressure was maintained throughout the surgery by continuous cuff pressure monitoring. A lubricated gastric tube was passed through the gastric channel in the i-gel and PLMA groups. The device was connected to a closed circle breathing system (Fabius® plus anesthesia work station, Draeger, Germany) and an effective airway was defined by a square wave capnograph trace, normal chest movements, stable oxygen saturation (SpO2) not less than 95% and bilateral auscultation of the chest.

At the end of the surgery, anesthetic agents were discontinued and the device was removed after the child was awake. Any blood staining of the device or tongue-lip-dental trauma was documented immediately in the post anaesthesia care unit and 24 h later. The parents were also asked about sore throat, hoarse cry or any other discomfort in the child's throat.

Monitoring devices (IntelliVue MP40™; Phillips Medical System, Eindhoven, Netherlands) were attached to the patient, including pulse oxymeter and noninvasive blood pressure. The following parameters were measured:

Hemodynamic parameters (heart rate and noninvasive blood pressure).

The OSP by closing the expiratory valve of the circle system at a fixed gas flow of 3 L/min, observing the airway pressure at which equilibrium was reached. At this point, gas leakage was heard at the mouth, at the epigastrium (epigastric auscultation) or coming out of the drainage tube (ProSeal and i-gel group). Manometric stability test was supposed to be the most reliable test.

Number of insertion attempts and ease of insertion.

Number of insertion attempts of gastric tube (ProSeal and i-gel groups).

-

Incidence of airway complications by these supraglottic devices:

- Presence of blood on LMA

- Tongue-lip-dental trauma

- Sore throat, hoarse cry.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Sample size was based on a crossover pilot study of 10 patients and was selected to detect a projected difference of 30% between the groups for airway sealing pressure for a type 1 error 0.05 and a power of 0.8. The demographic data (age, weight and height) were analyzed by ANOVA. The OSP and hemodynamic data were also compared using ANOVA. The insertion characteristics and complications were analyzed with chi-square test. Fisher's exact test was used to analyze the insertion attempts of gastric tube. Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as mean (SD). A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

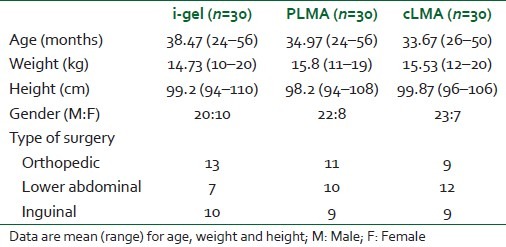

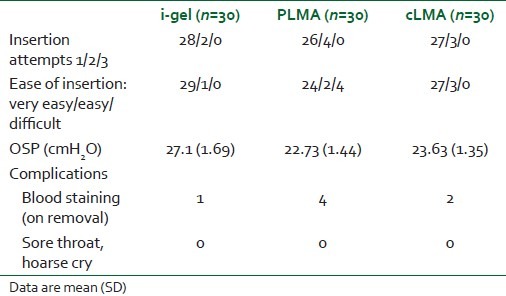

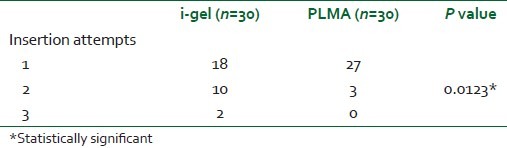

There was no significant difference in demographic data in the three groups [Table 1]. There were no failures in insertion of the airway in any group. The number of attempts of insertion was comparable and is shown in Table 2. Ease of insertion was similar in the i-gel and cLMA groups (no “difficult” insertion) compared with the PLMA group (four “difficult” insertions) [Table 2]. A gastric tube was easily passed through all PLMAs (10 Fr), but the recommended size (12 Fr) of the gastric tube for a size 2 i-gel was not easily passed through the airway. A significant number (P<0.05) of second and third attempts were required to insert a 12 Fr gastric tube through the gastric channel of the i-gel [Table 3]. The mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR) and SpO2 were comparable in all patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

Table 2.

Comparison in the three groups: i-gel, LMA ProSeal and LMA classic

Table 3.

Number of gastric tube insertion attempts

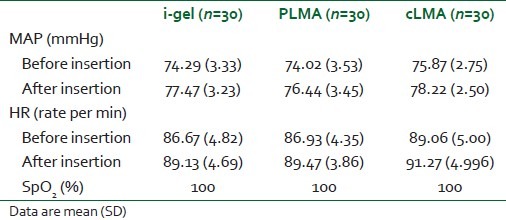

There was neither desaturation nor any significant change in MAP and HR before and after insertion of airway in any case, as shown in Table 4. There was no laryngospasm in any patient.

Table 4.

Hemodynamic parameters

The OSP was 27.1±1.69, 22.73±1.44, 23.63±1.35 cmH2O for the i-gel, PLMA and cLMA groups, respectively. The OSP between PLMA and cLMA was comparable, but there was a statistically significant difference between the i-gel and the other groups (P<0.05).

Blood staining was observed in four and two cases each in the PLMA and cLMA groups, respectively, and in one case in the i-gel group. There was no incidence of sore throat or hoarse cry in any of the three groups.

DISCUSSION

The i-gel is a new single-use, noninflatable supraglottic airway for use in anesthesia during spontaneous or intermittent positive-pressure ventilation.[4] The i-gel airway is an anatomically designed mask made of a gel-like thermoplastic elastomer with a soft durometer and gel-like feel.[5] The pediatric i-gel is a new smaller model of the well known i-gel used in adult patients. It has a channel for gastric catheter placement, except for size 1.[2] The soft, noninflatable cuff fits snugly onto the perilaryngeal framework, mirroring the shape of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, piriform fossae, perithyroid, peri-cricoid, posterior cartilages and spaces. Thus, each structure receives an impression fit, supporting the seal by enveloping the laryngeal inlet. The seal created is sufficient for both spontaneously breathing as well as paralyzed patients. Studies in adults have been promising, showing an easy insertion, high airway leak pressures and low complication rates, with few postoperative complaints.[6–10] In this study, we found that insertion of the i-gel was successful on the first attempt in 28 of 30 patients and comparable to 26 of 30 in the PLMA group and 27 of 30 in the cLMA group. A global study involving 50 children undergoing ventilation using the i-gel pediatric device was carried out over 2 months. In that study, the success rate for inserting the device was 80% on the first attempt and 100% after two attempts.[11,12] Other studies of using the pediatric i-gel[13] and LMAs[14,15] have shown similar results. The ease of insertion was graded as easy or very easy in all the cases in the i-gel and the cLMA groups and 86.67% (four of 30) in the PLMA groups. This higher number of difficult insertions in the PLMA group may be explained by the relative anatomy of the pediatric orohypopharynx and the bowl of the PLMA. The larger bowl of PLMA is more difficult to insert in the mouth and is more likely to fold over. Particularly, a relatively large tongue, a floppy epiglottis, a cephalad and more anterior larynx and frequent presence of tonsillar hypertrophy may disturb PLMA insertion in pediatric patients,[16] whereas the i-gel and cLMA are easier to insert because of a noninflatable cuff and smaller bowl, respectively.

Although the size 2 i-gel is supposed to allow a larger gastric tube (maximal 12 Fr) compared with the PLMA (10 Fr), we experienced difficulty in passing a 12 Fr tube through the gastric channel of the i-gel. The number of second attempts for passing the gastric tube (12 Fr) in the i-gel group was significantly higher compared with the PLMA group (10 Fr tube). As the diameter of the gastric channel is equal in both the i-gel and in the PLMA groups, of size 2,[17] we believe that a 10 Fr gastric tube would be a better option for the size 2 i-gel.

Comparisons of pediatric PLMA with cLMA have shown very little differences in the OSP because of absence of dorsal cuff in PLMA. Shimbori et al.[15] found an OSP of 18 cmH2O and 19 cmH2O with pediatric PLMA and cLMA, respectively, whereas Karippacheril et al.[14] reported 23.11 and 23.26 cmH2O for these devices. Goldmann et al.[18] measured an OSP of 18.8±4.8 cmH2O with size 2 PLMA and 15.0±4.5 cmH2O with the cLMA by detecting audible sounds at the mouth. Manometric stability method was used in both these studies. In our study, we observed an OSP of these three devices comparable to Goyal et al.[17] This observation is further substantiated by Beylacq et al. (25 cmH2O) and Bopp et al. (25.1±4.7 cmH2O).[13,11]

The incidence of complications (airway trauma and sore throat) was very low in all cases, except for blood staining in a few children in the PLMA and cLMA groups, which was neither clinically important nor statistically significant. Other studies have also reported a similar incidence.[13,14] Although i-gel inserts less pressure on the perilaryngeal tissue because of its noninflatable cuff, the incidence of sore throat was comparable in all three groups. This observation of our study is supported by the study of Wong et al.,[19] where they stated that sore throat could be minimal even with supraglottic devices with inflatable cuff, if the intracuff pressure remains less than 60 cm H2O.

CONCLUSION

From our study, we conclude that size 2 i-gel is comparable to PLMA and cLMA of the same size in terms of hemodynamic parameters, ease of insertion and post-operative complications. OSP is the only parameter that is significantly higher in the i-gel group. Size 2 i-gel is equally safe, efficient and cost-effective in children compared with other prototypical pediatric supraglottic airway devices. It has an added advantage of gastric channel, which is found only in PLMA and LMA supreme™. Therefore, i-gel should be more frequently used in children in both elective surgeries and in procedures requiring anesthesia outside the operating room.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verghese C, Brimacombe JR. Survey of laryngeal mask airway usage in 11,910 patients: safety and efficacy for conventional and nonconventional usage. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:129–33. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199601000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levitan RM, Kinkle WC. Initial anatomic investigations of the I-gel airway: A novel supraglottic airway without inflatable cuff. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1022–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Userguides/i.gel_users_Guide_English.pdf [Internet] 2010. [cited 2012 Jan10]. Available from: http://www.i.gel.com/

- 4.Gabbot DA, Beringer R. The iGEL supraglottic airway: A potential role for resuscitation? Resuscitation. 2007;73:161–4. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma S, Rogers R, Popat M. The I-gel™ airway for ventilation and rescue intubation. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:412–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson KM, Cook TM. Evaluation of four airway training manikins as patient simulators for the insertion of eight types of supraglottic airway devices. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:388–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.04983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keijzer C, Buitelaar DR, Efthymiou KM, Srámek M, ten Cate J, Ronday M, et al. A comparison of postoperative throat and neck complaints after the use of the i-gel and the La Premiere disposable laryngeal mask: A double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1092–5. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b6496a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francksen H, Renner J, Hanss R, Scholz J, Doerges V, Bein B. A comparison of the i-gel with the LMA-Unique in nonparalysed anaesthetised adult patients. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1118–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richez B, Saltel L, Banchereau F, Torrielli R, Cros AM. A new single use supraglottic airway device with a noninflatable cuff and an esophageal vent: An observational study of the i-gel. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1137–9. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318164f062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theiler LG, Kleine-Brueggeney M, Kaiser D, Urwyler N, Luyet C, Vogt A, et al. Crossover comparison of the laryngeal mask supreme and the i-gel in simulated difficult airway scenario in anesthetized patients. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:55–62. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a4c6b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bopp C, Chauvin C, Schwaab C, Mayer J, Marcoux L, Diemunsch P. L’I-gel en chirurgie pediatrique: serie initiale. 51eme Congres National d’Anesthesie et de Reanimation (SFAR) Paris, 23-26 September 2009. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2009:28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bopp C, Carrenard G, Chauvin C, Schwaab C, Diemunsch P. The I-gel in paediatric surgery: initial series. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Annual Meeting; New Orleans, USA, 17–21 October. 2009:A147. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beylacq L, Bordes M, Semjen F, Cros AM. The i-gel, a single use supraglottic airway device with a non-inflatable cuff and an esophageal vent: An observational study in children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:376–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karippacheril JG, Varghese E. Crossover comparison of airway sealing pressures of 1.5 and 2 size LMA-ProSeal™ and LMAClassic™ in children, measured with the manometric stability test. Pediatr Anesth. 2011;21:668–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimbori H, Ono K, Miwa T, Morimura N, Noguchi M, Hiroki K. Comparison of the LMA-ProSeal and LMAClassic in children. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:528–31. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ClinicalTrial.gov [Internet]. Comparison of Two Insertion Techniques of Proseal Laryngeal Mask airway by unskilled personnel in children. [updated 2010 Aug 30; cited 2012 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01191619 .

- 17.Goyal R, Shukla RN, Kumar G. Comparison of size 2 i-gel supraglottic airway with LMAProSeal™ and LMA-Classic™ in spontaneously breathing children undergoing elective surgery. Pediatr Anesth [Internet] 2011. Dec, [cited 2012 Jan10]. Available from: http://www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1460.9592.2011.03757.x . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Goldmann K, Jakob C. Size 2 ProSeal™ laryngeal mask airway: a randomized, crossover investigation with the standard laryngeal mask airway in paediatric patients. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:385–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong JG, Heaney M, Chambers NA, Erb TO, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Impact pf laryngeal mask airway cuff pressures on the incidence of sore throat in children. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:464–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.02968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]