Abstract

In wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings subjected to a mild water stress (water potential of −0.3 MPa), the leaf-elongation rate was reduced by one-half and the mitotic activity of mesophyll cells was reduced to 42% of well-watered controls within 1 d. There was also a reduction in the length of the zone of mesophyll cell division to within 4 mm from the base compared with 8 mm in control leaves. However, the period of division continued longer in the stressed than in the control leaves, and the final cell number in the stressed leaves reached 85% of controls. Cyclin-dependent protein kinase enzymes that are required in vivo for DNA replication and mitosis were recovered from the meristematic zone of leaves by affinity for p13suc1. Water stress caused a reduction in H1 histone kinase activity to one-half of the control level, although amounts of the enzyme were unaffected. Reduced activity was correlated with an increased proportion of the 34-kD Cdc2-like kinase (an enzyme sharing with the Cdc2 protein of other eukaryotes the same size, antigenic sites, affinity for p13suc1, and H1 histone kinase catalytic activity) deactivated by tyrosine phosphorylation. Deactivation to 50% occurred within 3 h of stress imposition in cells at the base of the meristematic zone and was therefore too fast to be explained by a reduction in the rate at which cells reached mitosis because of slowing of growth; rather, stress must have acted more immediately on the enzyme. The operation of controls slowing the exit from the G1 and G2 phases is discussed. We suggest that a water-stress signal acts on Cdc2 kinase by increasing phosphorylation of tyrosine, causing a shift to the inhibited form and slowing cell production.

A decrease in soil water potential due to drought or salinity decreases the rate of leaf expansion, whereas root expansion is much less affected (Munns and Sharp, 1993). If the root water potential decreases suddenly, the response of leaf expansion is so rapid and large (Cramer and Bowman, 1991) that it must be due to a change in the rate of expansion of existing cells, rather than to a change in the rate of production of new cells. However, when plants have grown for some time in soils of low water potential, smaller leaves with fewer cells are formed (Clough and Milthorpe, 1975; Randall and Sinclair, 1988; Lecoeur et al., 1995). These observations suggest that reduced cell formation during water stress may limit final leaf size.

Little is known about the effects of water stress on rates of cell division or on mitotic activity in leaves. Roots have received more attention. In roots there was a rapid decrease in mitotic activity after imposition of water stress (Yee and Rost, 1982; Robertson et al., 1990b; Bitonti et al., 1991; Bracale et al., 1997), and a similar response was found for soybean hypocotyls (Edelman and Loy, 1987). These sudden decreases in mitotic activity suggest, but do not prove, that water stress caused a sudden decrease in the rate at which new cells were being produced. To our knowledge, the only study to measure rates of cell production under water stress was done by Sacks et al. (1997), who found a 40% reduction in the rate of cell division in cortical cells of the primary root of water-stressed maize.

Evidence that the extent of cell production may limit growth has come from the stimulation of root growth that follows increased expression of a cyclin cell-cycle gene in Arabidopsis (Doener et al., 1996). The product of the cdc2 (cell-division-cycle) gene, the protein kinase p34cdc2 (Nurse, 1990), here referred to as Cdc2 kinase, plays a major role in driving the cell cycle. Genetic analysis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe has shown that cdc2 function is required at the start of the S phase and at entry into mitosis (Nurse and Bissett, 1981). The Cdc2 kinase is the first discovered member of a group of CDKs found in higher eukaryotes that require association with a cyclin protein to become enzymically active (Norbury and Nurse, 1992).

At mitosis the Cdc2 kinase is the dominant active CDK; at this time its activity is severalfold higher than at other times in the cell cycle (Tsai et al., 1991; for review, see Stern and Nurse, 1996). This drives the structural changes of nuclear envelope disassembly, chromosome condensation, and mitotic spindle assembly in yeasts and animals (for review, see Nurse, 1990; Nigg, 1995) and in plants (Hush et al., 1996). The importance of the Cdc2 kinase in cell division in plants was indicated by the ability of plant cdc2 genes to support division in yeasts (Hirt et al., 1991) or, in the negative mutant form, to block division in plants (Hemerly et al., 1995). The importance of Cdc2 is further indicated by the positive correlation of cdc2 gene expression with regions of cell division (Gorst et al., 1991; John et al., 1991; Martinez et al., 1992; Hemerly et al., 1993; for review, see John, 1996). Furthermore, a role of mitotically active CDK in driving plant mitosis is directly shown by the stimulation of mitosis that is induced by injection of the mitotically active form of plant Cdc2 protein into stamen hairs of Tradescantia virginiana (Hush et al., 1996).

Activation of Cdc2 kinase at the initiation of mitosis requires the binding of mitotic cyclin and the phosphorylation of Thr and Tyr residues before catalytic activity is released by the removal of phosphate from Tyr 15 (and also from Thr 14 in animal cells) by Cdc25 phosphatase (Norbury and Nurse, 1992). As cells approach mitosis there is a decline in the abundance of inactive Tyr-phosphorylated enzyme and an increase in active Tyr-dephosphorylated enzyme (Russell and Nurse, 1986, 1987; Moreno et al., 1990; Lew and Kornbluth, 1996). The same decline in Tyr phosphorylation of Cdc2 kinase has recently been detected as the mechanism of cytokinin induction of plant mitosis (Zhang et al., 1996). This is an important element in regulating plant cell division and here we report its contribution to environmental responses.

To investigate possible environmental influence over cell division in the developing leaf, we subjected wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings to a mild (soil) water stress at a very early stage of development and recorded the spatial extent of mitotic activity throughout leaf development. Previous publications showed that only in leaves that were very small at the onset of a water stress (e.g. 2% of final leaf area; 5% of final cell number) was the number of cells produced per leaf affected by stress (Clough and Milthorpe, 1975; Randall and Sinclair, 1988; Lecoeur et al., 1995). Calculations from Foard and Haber (1961) indicated that less than 3% of the mesophyll cells in the first leaf of a wheat seedling are formed during seed development; therefore, we used germinating wheat seedlings maintained in the dark at high humidity to study the effects of a mild and steady water stress that would have an impact on the plant at an early stage of leaf development.

We measured the effect of stress on the spatial extent of cell division throughout leaf development to locate the tissue most responsive to stress. We focused on mesophyll cells rather than other cell types because mesophyll cells are the major cell type in leaves and make the greatest contribution to the volume of this tissue. Epidermal cells, which have been the subject of most studies of cell expansion or division, have a much shorter zone of division than do mesophyll cells (associated with their larger final dimensions), and preliminary observations showed that their mitotic activity was restricted to the basal few millimeters of the leaf and terminated sooner than that of mesophyll cells (data not shown). We then investigated whether mild water stress in the wheat leaf affects regulation of the cell cycle by testing for effects on cell-cycle progression and on Cdc2 kinase activity. We report evidence that water stress has rapid effects on Tyr phosphorylation and activity of a Cdc2-like enzyme and propose that these contribute to reduced cell-division activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth Conditions

Wheat (Triticum aestivum cv Kite) seeds were soaked in water for 24 h in a Petri dish and then transferred to pots 10 cm wide and 25 cm deep containing vermiculite that was either fully or partially hydrated with water. Seeds were placed about 5 cm beneath the surface of the vermiculite. The level of hydration that reduced leaf elongation rate by about 50% was found to be 22% (grams of water per gram of vermiculite), which had a water potential of −0.3 MPa as determined with an isopiestic psychrometer (Boyer and Knipling, 1965). Seedlings were grown at 23°C in the dark in a humidified chamber. This method was chosen because the lack of transpiration meant that the soil water was not depleted and that the plant water potential would not change. Transplanting and nondestructive length measurements were done under a green safelight giving less than 0.1 μmol PAR m−2 s−1.

Measurement of Blade-Elongation Rate

Lengths of leaf 1 were measured from leaf base to tip with a ruler every 24 h on 30 replicates, and the position of the ligule was recorded under a dissecting microscope. Sheath lengths were subtracted from the total leaf length, and blade lengths were recorded until the blade was fully elongated. Seed reserves were still adequate for growth at this stage but were depleted before the sheath finished growing. This experiment was carried out four times. In one experiment the second leaf was dissected and measured.

Measurement of Mitotic Activity

For microscopic analysis 10 leaves with lengths closest to the mean of 30 leaves were chosen. Because the stressed leaves were elongating at only about one-half the rate of the controls, samples from the stressed plants were taken every 2nd d after d 2. Samples were always taken at the same time of day. The basal 30 mm of the shoot was excised, fixed in formalin-acetic acid-70% ethanol (1:1:18), dehydrated in an ethanol-t butanol series under vacuum, and infiltrated with paraffin (Paraplast Plus, Sherwood Medical Laboratories, St. Louis, MO; melting point 56–57°C) according to the method of Volenec and Nelson (1981). Longitudinal 8-μm-thick sections were hydrolyzed with 1 n HCl for 10 min at 60°C, stained with Schiff's reagent for 16 h by the Feulgen method, and counterstained with Fast Green (CI 42053, Sigma; 0.01% in 95% ethanol for 30 s).

The mitotic index of the mesophyll cells of the first leaf was estimated by scoring the percentage of cells in the two cell layers beneath each epidermis that were clearly in metaphase, anaphase, or telophase. Prophase was not always distinctive, therefore, this phase was not scored. This was done for consecutive fields of view; for a given section, cells along the entire meristem were examined. In total, 32 files of cells were measured in eight sections from four different leaf samples for each period. The position of the ligule was recorded. The data are presented as the distances from the base of the leaf or from the ligule, if present, in segments of 0.45 mm.

In harvesting plants at 24-h intervals, we assumed that there would be no synchrony of cell division, which is the usual situation for plants grown under constant conditions. This assumption was later confirmed by the absence of coordinated mitotic events observed across the tissue and by the constancy of CDK activity, which increases in the G2 phase (Zhang et al., 1996), but was found to have a similar activity in tissue harvested at many times during a 24-h time course (see Results).

Estimation of Final Cell Number per Leaf

Final cell size was measured in leaf blades harvested at d 7 (unstressed) or d 12 (stressed) of treatment in two additional experiments replicated for this purpose. Measurements of cell length were made on the layer of mesophyll cells below the epidermis after clearing with methanol (10 min at 70°C) and lactic acid. Because mature mesophyll cells in wheat vary in length and shape with position in the leaf (Jung and Wernicke, 1990), leaves were divided into quarters along their length, and the average cell length for each quarter was estimated. Ten cells were measured in each quarter of nine leaves from each of the two experiments (a total of 90 cells for each part of the leaf per treatment). The total number of cells produced in a given file along the blade of the fully expanded leaf of stressed plants was calculated from the lengths of the mature leaf and cells.

Plant Material for Cell-Cycle Experiments

For most experiments plants were harvested 48 h after transfer to vermiculite. At this stage the first leaf of the unstressed plants averaged 17 mm in length, and that of the stressed plants averaged 8 mm. At this stage the second leaf was only 2 mm long in the unstressed plants and one-half of this in the stressed plants. The shoot was cut at its base from the seed coat, and 3-mm segments were dissected starting from the base, covering the meristem, and in some experiments extending beyond it. In most experiments only the segments 0 to 3 mm and 3 to 6 mm from the base were examined, because these contained the most actively dividing tissue. Segments were frozen immediately in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C.

For the time-course experiment seeds were soaked for 24 h as usual and were then transplanted to pots containing fully hydrated vermiculite for another 36 h before a second transfer to pots containing either fully or partially hydrated vermiculite. The period of 36 h in well-watered conditions permitted the seedlings to grow sufficiently long to allow dissection into two 3-mm segments at the start of the stress treatment. This treatment is called the “transplantation protocol” to distinguish it from the procedure used in most of the experiments.

Biochemical Techniques

Purification of a Cdc2-like protein was carried out by grinding the leaf segments in liquid N2 and mixing vigorously at 0°C with NDE buffer (20 mm Hepes, 50 mm β-glycerophosphate, 15 mm MgCl2, 20 mm EGTA, 5 mm NaF, 2 mm DTT, 5 μm leupeptin, 5 μm pepstatin, 2 μg/mL aprotinin, 0.5 mm sodium orthovanadate, 10 μm ammonium molybdate, and 10 mg/mL sodium 4-nitrophenylphosphate, with PMSF added to 0.5 mm final concentration immediately before use), pH 7.4. Protein extracts were incubated for 2 h at 4°C with 40 μL of bead suspension (20-μL beads containing 8 mg p13/mL beads, which are hereafter referred to as p13 beads) to bind the Cdc2-like protein (John et al., 1991; Hepler et al., 1994).

The beads were washed twice at 0°C with 400 μL of 5 mm Na2HPO4, 4 mm NaH2PO4, 2 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P40, 5 μg/mL leupeptin, 0.1 mm sodium vanadate, and 50 mm NaF, pH 7.0, and then washed once with HBK (25 mm Hepes, 1 mm EGTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 160 mm KCl, and 1 mm DTT). Cdc2-like protein was eluted from the beads by incubation for 10 min at 4°C with 45 μL of free p13suc1 (0.5 mg/mL) in HBK, and the beads were discarded by centrifugation. The activity of the purified protein was measured immediately in a kinase assay. Linear recovery of enzyme was obtained from amounts of extract containing less than 350 μg of protein incubated with 20 μL of p13 beads.

The kinase assay was carried out on 20 μL of purified Cdc2-like protein in an incubation volume of 50 μL (John et al., 1991; Zhang et al., 1996), with the modification that 20 μL of the terminated assay was spotted onto Whatman P81 paper and washed five times for 3 min in 75 mm H2PO4, and the radioactivity was determined in a scintillation counter to quantify the amount of [32P]PO4 transferred to H1 histone.

To estimate the level of Cdc2-like protein relative to other proteins, total protein was extracted from leaf tissue, frozen, and ground in liquid N2 into NDE buffer (John et al., 1990). Fifty-microgram samples of leaf protein were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12% acrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with antibody against the 16-amino acid region EGVPSTAIREISLLKE, which is universally conserved in all known cdc2 molecules, as described previously (Lee and Nurse, 1987; John et al., 1989, 1990). Bound antibody was detected with 125I-anti-rabbit IgG F(ab′)2 at 0.5 mCi/L (IM1340, Amersham) visualized by 72-h exposure to a phosphor-imaging screen. Samples to be compared were electrophoresed and transferred onto the same piece of nitrocellulose.

To measure the Tyr-phosphorylation state, the enzyme was purified with p13suc1 beads from samples of extract containing 300 μg of protein, separated by 12% acrylamide SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, blocked with 1% BSA in buffered saline, and probed with anti-phospho-Tyr antibody (mouse monoclonal PY-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and rabbit anti-mouse antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) as described by Zhang et al. (1996). Bound antibody was detected with 125I-anti-rabbit IgG F(ab′)2 at 0.5 mCi/L (IM1340, Amersham) after 72 h of exposure to a phosphor-imaging screen.

Measurement of G1/G2 Frequency

The frequency of G1- and G2-phase nuclei was measured in longitudinal sections of leaves after 48 h of treatment, which were embedded in paraffin and stained by the Feulgen method. The cells measured were those in the two layers adjacent to both epidermes, i.e. the cells destined to become mesophyll cells. The intensity of nuclear staining was quantified using a Nikon Optiphot microscope with white light. Images obtained with a SIT television camera (Dage MTI, Michigan City, IN) were recorded in digitized form using an image-processing attachment (Image-1, Universal Imaging Corp., Chester, PA) and analyzed using imaging software (Image-1, version 4.0, Universal). A minimum area enclosing the whole nucleus was measured, and for each cell a background intensity was estimated from the average of three areas of the same size in the adjacent cytoplasm. The background was subtracted for each cell. Only nuclei in sharp focus were measured, and the focus was adjusted until all intact nuclei in the field of view had been measured. Data were collected from eight sections from three different leaves from each treatment.

RESULTS

Effect of Water Stress on Leaf-Blade Elongation

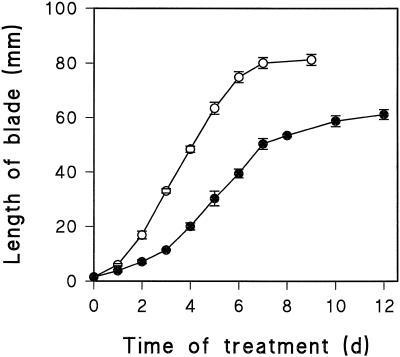

Water stress caused the rate of elongation of the leaf blade to decrease to 51% of the unstressed plants for the 1st d and then to an average of 41% for the next 4 d (Fig. 1). After this, the elongation rate of the unstressed plants slowed down, and that of the stressed plants continued for several more days, with the result that the final blade length of the stressed plants reached 73% of the unstressed plants.

Figure 1.

Increase in blade length of the first leaf of wheat in fully hydrated (unstressed; ○) and partially hydrated vermiculite at a water potential of −0.3 MPa (stressed; •). Treatment commenced at 24 h after imbibition. Bars show the ses of four experiments (n = 30).

The elongation rate of the second leaf was similarly affected. It was too small to be measured for the first 2 d of the treatment; then between d 3 and 5 it increased from 1.6 to 3.6 mm in length, and stress reduced this by one-half (data not shown).

Developmental Pattern of Mesophyll Cell Production in Unstressed Leaves

The cell-division activity in the unstressed wheat leaf blade throughout its development is summarized in Table I. This shows the length of the meristematic zone of mesophyll cells and the maximum mitotic index based on taking cells clearly in the mitotic phases of metaphase, anaphase, and telophase, but omitting prophase because its recognition was equivocal. After 24 h of imbibition, the mitotic index of mesophyll cells in the first leaf was about 3.5% at the leaf base, declining to 2.5% at the tip. One day later, the mitotic index was again about 3.5% at the base, declining gradually to 0 at the tip of the leaf, which was now 6 mm long. On d 2, mitotic activity in the leaf was at its maximum, both in terms of mitotic index and in the distance from the shoot base over which division occurred (Table I). The ligule started to develop at the base of the shoot meristem on d 2 and by d 3 had moved about 0.5 mm from the base. At this time, when the blade was 40% of its final length, the mitotic activity started to decline (Table I). By d 4, when the blade was about 60% of its final length, mitotic activity had declined further, and by d 5 was observed essentially only below the ligule, i.e. in sheath cells.

Table I.

Developmental pattern of mesophyll cell production in the first leaf of unstressed wheat seedlings

| Time | Blade Length | Meristematic Zone Length | Maximum Mitotic Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| d | mm | % | |

| 0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.6 ± 0.3 |

| 1 | 6 | 6 | 3.3 ± 0.3 |

| 2 | 17 | 8 | 4.4 ± 0.7 |

| 3 | 33 | 6 | 2.5 ± 0.5 |

| 4 | 48 | 4 | 1.1 ± 0.5 |

| 5 | 64 | 2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| 6 | 75 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 81 | 0 | 0 |

Measurements started after 24 h of imbibition. The final blade length was reached on d 7. The ligule was present at d 3; therefore, only activity distal to this is recorded. The data are an average of four separate experiments. ses are given for the mitotic index. ses for the blade length are shown in Figure 1. The meristem length is rounded off to the nearest 0.5 mm.

Comparison between Stressed and Unstressed Leaves in Spatial Extent and Duration of Mitotic Activity in Mesophyll Cells

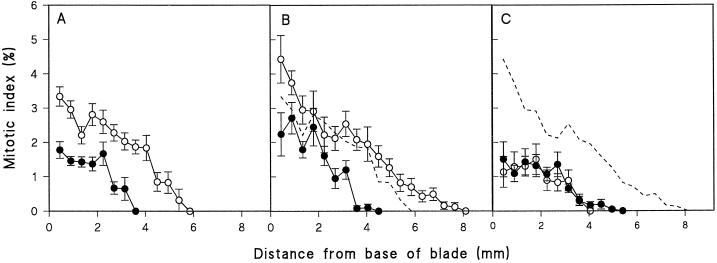

After only 1 d of treatment, the mitotic activity in the stressed leaves was much reduced, the maximum mitotic index being only one-half of that in the unstressed controls, and declining to 0 at the tip of the respective leaves from each treatment (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Mitotic index of mesophyll cells as measured in longitudinal sections taken from the blade of the first leaf of wheat seedlings from unstressed (○) and stressed treatments (•) as defined in Figure 1 after 1 d (A), 2 d (B), or 4 d (C) of treatment. Bars show the ses (n = 32). The dotted line on B and C is the “developmental control,” i.e. the mitotic index of unstressed leaves of the same size as the stressed leaves (see text for further explanation).

On d 2, when mitotic activity was at its greatest in both unstressed and stressed leaves, the maximum mitotic index in the stressed plants was only one-half of that in the controls, and the zone of division was much shorter (Fig. 2B). Comparison with unstressed leaves at a similar total length (seen in Fig. 2A, and superimposed on Fig. 2B as a dotted line) shows that the meristematic activity in the stressed leaf was still much reduced in comparison with a control leaf at a similar developmental stage.

On d 4 of treatment the division activity in the leaves of unstressed plants was nearing completion, whereas the activity in leaves of the stressed plants was continuing; therefore, the division activity of the two treatments coincided (Fig. 2C). However, the mitotic activity in the stressed leaves was much more reduced than in unstressed leaves of similar length, i.e. d-2 control leaves (superimposed as a dotted line in Fig. 2C). By d 5, the division of blade cells had almost ceased in the unstressed plants and mitotic activity occurred only below the ligule. In the stressed plants mitotic activity continued in blade tissue until d 7, and by d 8 division occurred only below the ligule (data not shown). Therefore, the duration of division was much longer in stressed leaves than in the controls, as was the duration of leaf elongation (Fig. 1).

The total number of cells produced per file was calculated from the final length of the mature leaf blade, which was 81 ± 2 and 59 ± 3 mm for unstressed and stressed plants, respectively (Fig. 1), and from the average length of mature cells, which was 66 ± 3 and 56 ± 2 μm for unstressed and stressed leaves, respectively. This showed that the stressed leaf produced 86% of the cells produced in the unstressed controls along a file. Transverse sections along the blade in both the meristematic zone and in the fully expanded leaves showed that there was no reduction in the number of files of cells in stressed leaves; therefore, the total number of cells in the whole blade of the stressed plants was also 86% of that in the controls.

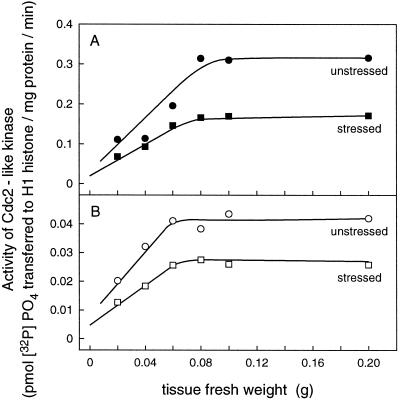

Effect of Water Stress for 48 h on Cdc2-Like Kinase Activity in the Leaf Base

The basal 6 mm of the shoot was dissected into two segments. The first segment contained the basal 3 mm of the shoot, and the second contained the region from 3 to 6 mm from the base. The kinase was purified from the tissue using p13suc1. Affinity chromatography using p13 beads and elution with free p13suc1 has previously been used to recover Cdc2-like protein from extracts of leaf meristem cells of wheat (John et al., 1991). Figure 3 shows recovery from different amounts of wheat tissue extract using 20 μL of p13 beads containing 160 μg of p13suc1. A linear recovery of activity was obtained for up to 0.06 g fresh weight of tissue from both stressed and unstressed plants. This indicates similar cell contents of the enzyme, since Cdc2 protein forms a semistable complex with p13suc1 (Brizuela et al., 1987; Endicott and Nurse, 1995), and the beads become saturated with kinase when all available sites are filled. This causes a plateau in recovery from increasing amounts of extract protein. In the experiments described in Figures 4–6, 0.05 g of seedling leaf tissue was used to avoid bead saturation. The data in Figure 3 indicate that the amount of the Cdc2-like protein was not altered by stress but the proportion of active enzyme was reduced.

Figure 3.

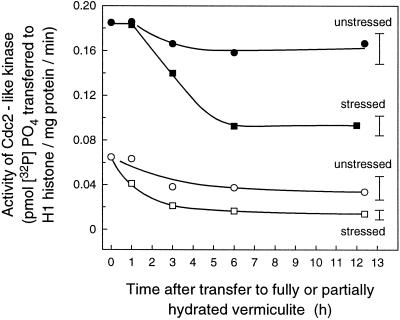

Recovery of Cdc2-like kinase using p13suc1 affinity chromatography with 20-μL p13 beads from extracts of leaf segments from unstressed (○, •) and stressed (□, ▪) plants after 48 h of treatment. A, Tissue 0 to 3 mm from leaf base. B, Tissue 3 to 6 mm from leaf base. Activity is related to milligrams of total extracted protein applied to p13 beads for purification prior to assay.

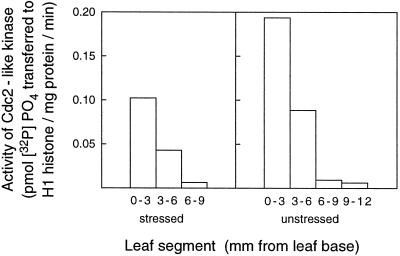

Figure 4.

Activity of Cdc2-like kinase purified from extracts of leaf segments taken sequentially from the bases of the leaves of stressed and unstressed plants after 48 h of treatment.

Figure 6.

Change with time in Cdc2-like kinase activity in leaves of plants that were first grown on fully hydrated vermiculite for 36 h and then transplanted to pots containing either fully or partially hydrated vermiculite at a water potential of −0.3 MPa (the transplantation protocol). Extracts were made from tissue 0 to 3 mm and 3 to 6 mm from the leaf base from unstressed and stressed plants and were purified before assay. •, Unstressed, 0 to 3 mm; ○, unstressed, 3 to 6 mm; ▪, stressed, 0 to 3 mm; and □, stressed, 3 to 6 mm. Bars show the average ses for all sampling times (mean of four assays).

Figure 4 shows the activity of an affinity-purified Cdc2-like enzyme from 48-h stressed and unstressed wheat seedlings taken up to 12 mm from the base of the leaf. Activity was about 50% lower in extracts from the stressed than the unstressed leaves in both the 0- to 3-mm and 3- to 6-mm segments, and only very low activity was detected 6 to 12 mm from the base.

The Cdc2-like activity in these extracts from the basal shoot tissue (Fig. 4) did not correlate perfectly with mitotic activity shown above for mesophyll cells in stressed and unstressed leaves from plants treated for the same period of time (Fig. 2B). This is because the basal shoot tissue contains a mixture of cell types. Mesophyll cells are the predominant cell type, but there are also cells in the epidermal and vascular tissue. Epidermal cell division in the developing leaf terminates well ahead of mesophyll cell division (because of their larger final length, their numbers are fewer), and division within the vascular tissue proceeds much later and farther from the base than does mesophyll tissue (U. Schuppler, P.-H. He, P.C.L. John, and R. Munns, unpublished observations). Nevertheless, there was strong similarity in the pattern of mitotic activity of mesophyll cells and Cdc2-like enzyme activity in the total shoot base, both in the degree of activity and in the spatial extent.

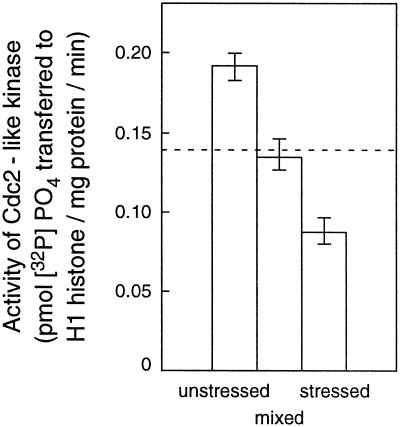

To test whether the lower kinase activity in extracts from the stressed leaves was due to the presence of nonspecific inhibitory or denaturing molecules that could have been elevated by stress, ground, frozen powder from unstressed leaves was mixed with equal amounts from stressed leaves before purification. The kinase activity of this mixture was compared with that of unmixed extracts. Assays were carried out in triplicate. Figure 5 shows that the activity of the mixed extracts from stressed and unstressed plants was the same as the average of the unmixed extracts, indicating that there was no in vitro inhibition of the activity in extracts from stressed tissue.

Figure 5.

Comparison of activity of Cdc2-like kinase purified from extracts of leaf segments taken from the basal 0 to 3 mm of leaves from unstressed and stressed leaves after 48 h of treatment with that purified from mixed extracts of the same tissues mixed in a 1:1 ratio. The broken line is the calculated mean of stressed and unstressed extracts. Bars show the ses (mean of three separate kinase assays).

Speed of Effect of Water Stress on Cdc2-Like Kinase Activity

Kinase activity was measured over time in plants that had been grown under unstressed control conditions in fully hydrated vermiculite for 36 h (rather then 24 h) after imbibition so that the first leaf was big enough to measure at the start of the stress (6–7 mm long). Plants were then transplanted to vermiculite at a water potential of −0.3 MPa or to fully hydrated vermiculite (the transplantation protocol). A response to water stress occurred by 3 h in the basal 3-mm segment, and activity declined to nearly 50% within 6 h (Fig. 6). In the adjacent segment, 3 to 6 mm from the base, reduction in activity was more rapid and detectable from 1 h after stress.

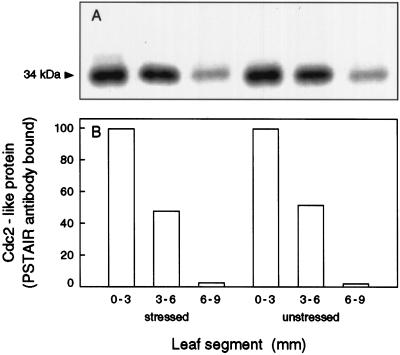

Effect of Water Stress on the Level of Cdc2-Like Protein

To further investigate the conclusion drawn from the experiments with p13-bead saturation (Fig. 3), that amounts of Cdc2-like protein were not altered by stress, the amount of protein was measured directly by probing western blots of total proteins extracted from stressed and control plants. The amount of the Cdc2-like protein was assayed by immunodetection of the PSTAIR region of Cdc2 proteins. An antibody raised against this peptide revealed a 15-fold higher concentration of Cdc2-like protein relative to total soluble proteins in the meristem region of the wheat leaf compared with other regions of the leaf (John et al., 1990). The same antibody was used to probe western blots of 50-μg protein samples from segments of 48-h stressed and unstressed plants (Fig. 7). Stress had not altered the amount of the Cdc2-like protein in either the first or second segments. This is consistent with the similar saturation of p13 beads by extracts (Fig. 3). The reduction of the kinase activity was therefore not due to a reduction in the level of PSTAIR-containing protein.

Figure 7.

Level of Cdc2-like protein in extracts from basal segments of stressed and unstressed leaf tissue after 48 h of treatment. A, Samples of total soluble protein separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred for western blotting, probed with PSTAIR antibody, and visualized with 125I-labeled anti-rabbit IgG F(ab′)2. B, Quantity of PSTAIR-containing 34-kD protein, in relative units measured by phosphor image analysis.

Effect of Water Stress on Frequency of G1- and G2-Phase Nuclei of Mesophyll Cells

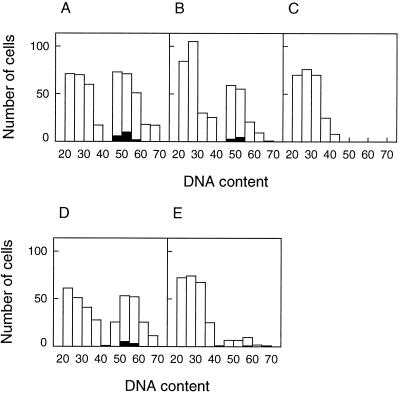

Water stress may affect Cdc2 kinase activity by slowing the progress between the G1 and S phase or between the G2 and M phase, with consequent changes in the abundance of G1 and G2 phase nuclei. Therefore, the DNA content of nuclei was estimated to establish the frequency of cells in the G1 and G2 phases. Because mitotic activity in mesophyll cells was observed up to 8 mm from the leaf base (Fig. 2), nuclei were measured in the basal 9 mm.

In the unstressed leaf the basal 3 mm, which contains the most actively dividing population of cells, approximately 50% of the cells were in G2 phase (Fig. 8A). In the next 3 mm 38% were in G2 phase (Fig. 8B). At 6 to 9 mm from the base of the leaf only G1 phase cells were observed (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8.

Frequency of mesophyll cell nuclei with DNA contents estimated by Feulgen stain, measured in longitudinal sections of leaves from unstressed and stressed plants after 48 h of treatment. A to C, Unstressed leaves. D to E, Stressed leaves. Mesophyll cells were scored in the basal 0- to 3-mm region of leaves (A and D) and the 3- to 6-mm region (B and E) and the 6- to 9-mm region of unstressed leaves only (C); cells in the 6- to 9-mm region of stressed leaves were entirely nonmitotic and arrested in G1 phase (not shown). Cells with DNA of 20 to 40 relative units were in G1 phase, and those with 45 to 70 units were in G2 phase. Open bars, Total nuclei; solid bars, nuclei in metaphase or anaphase.

In the stressed leaf the basal 3 mm resembled the control in having equal numbers of G1 phase and G2 phase nuclei (Fig. 8D), but in the next 3 mm there was a much reduced frequency of G2 cells, which contributed only 10% of the population (Fig. 8E). The lower incidence of G2 phase cells may reflect accelerated progression to cell differentiation, which in the wheat leaf requires arrest in the G1 phase.

Effect of Water Stress on Phosphorylation State of Cdc2-Like Protein

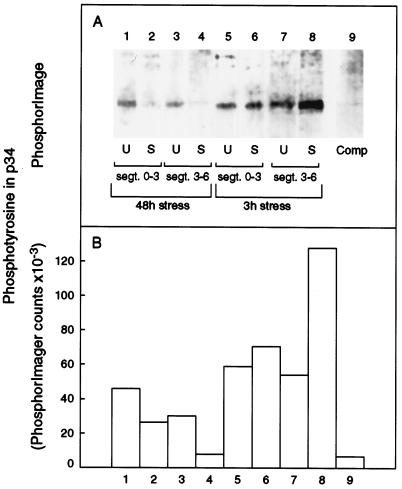

The early progress of mitosis in eukaryotes depends on the activation of the Cdc2 enzyme, which is determined by a decline in the inactive, Tyr-phosphorylated form. Using an anti-phospho-Tyr antibody, we assayed Tyr-phosphorylated Cdc2-like protein in unstressed and stressed tissue (Fig. 9) sampled after 3 h (lanes 5–9) and then after 48 h (lanes 1–4). As in the earlier time-course experiment, the transplantation protocol was followed (i.e. seedlings were grown in fully hydrated vermiculite for 36 h after imbibition before being transplanted to fully or partially hydrated vermiculite so that they were big enough to measure at the start of the stress). A markedly increased phospho-Tyr level was detected in the protein from the 3- to 6-mm segment after 3 h of stress (Fig. 9), which correlated with the rapid decline in enzyme activity in this segment (Fig. 6). A smaller increase in phospho-Tyr was apparent in the 0- to 3-mm segment (Fig. 9), which correlated with the smaller decline in activity that had developed in this segment by 3 h (Fig. 6). After 48 h of stress, levels of phospho-Tyr in the Cdc2-like protein of both leaf segments from stressed plants were lower than in controls, consistent with cells accumulating in G1 phase (Fig. 8) because of slow cell enlargement or a premature switch to differentiation. While in the G1 phase, Cdc2 protein is not phosphorylated at Tyr (Norbury and Nurse, 1992; Hayles et al., 1995; Stern and Nurse, 1996), and low activity arises by other mechanisms such as low G1-cyclin levels (Nasmyth, 1966; Sherr, 1996).

Figure 9.

Phospho-Tyr in 34-kD protein that was purified from 300-μg aliquots of total soluble protein by binding and elution with p13 beads. Alternate lanes carry purified enzyme from unstressed (U) and stressed (S) leaves taken from segments 0 to 3 mm (segt. 0–3) or 3 to 6 mm (segt. 3–6) from the base of the leaf. Plants were first grown on fully hydrated vermiculite for 36 h and then transplanted to pots containing either fully or partially hydrated vermiculite at a water potential of −0.3 MPa (the transplantation protocol). Plants were then sampled at 48 h (lanes 1–4) or 3 h (lanes 5–9). Lanes 1 through 8 were probed with anti-phospho-Tyr antibody and in lane 9 this antibody was precompeted (Comp) with 1 mm phospho-Tyr for 1 h before application to a duplicate of lane 8. A, Phosphor image of bound 125I second antibody. B, Quantification of phospho-Tyr in 34-kD protein measured by phosphor image analysis.

DISCUSSION

Effect of Water Stress on Mitotic Activity

Water stress quickly reduced the mitotic activity of mesophyll cells in the meristematic zone and reduced the zone of cell division. A shortening of the zone of cell division in roots by water stress has been reported for sunflower (Robertson et al., 1990b) and maize (Silk, 1992; Sacks et al., 1997). A rapid response of mitotic activity was observed in roots of fava beans exposed to −0.9 MPa PEG (Yee and Rost, 1982), of wheat and pea exposed to about −1.4 MPa mannitol (Bitonti et al., 1991; Bracale et al., 1997), and of sunflowers grown in aeroponic culture with reduced water supply (Robertson et al., 1990a, 1990b). In the studies with fava beans and sunflower, the mitotic index largely recovered after a few days, which suggests that the stress imposed was severe and sudden, and the plants later adjusted to some extent. In our experiments the stress was mild (−0.3 MPa), and the plant response was steady throughout.

Rates of cell division cannot be correctly inferred just from measurements of mitotic activity; there would be no change in the mitotic index or the spatial extent of mitosis if the cell-division rates changed in synchrony with growth rates (Ben-Haj-Salah and Tardieu, 1995; Sacks et al., 1997). However, the decrease in mitotic activity observed here does suggest that cell-division rates might be reduced. From the reduced zone of mitosis and the reduced incidence of mitotic activity in the basal 3 mm of the leaf, we consider it likely that there was a significant reduction in the rate at which cells were being produced. We consider it unlikely that the reduced mitotic index in stressed plants was due to cells passing more quickly through the phase of mitosis than in unstressed plants, in which the expansion phase was less inhibited. As water stress reduces rates of cell expansion in roots (Sharp et al., 1988) and leaves (Spollen and Nelson, 1994; Durand et al., 1995), it is more likely that water stress slows down the rate of cell expansion during the cell-enlargement phases of the cell cycle than that it hastens the mitotic phase in relation to the other phases.

A longer period of mitotic activity in the stressed leaves meant that the final number of cells produced was not so different from that in the unstressed leaves (86% of controls), but the time it took to achieve that final number, together with the incremental effect on subsequent leaves, means that growth of the stressed plant would decrease farther behind that of the controls.

Frequency of G1-/G2-Phase Cells

To test for possible preferential effects of a water-stress signal at particular cell-cycle control points, the abundance of cells in the G1 and G2 phases were measured. If progress through a G1 control point was preferentially slowed, we would expect to find an increased number of G1 phase cells and, conversely, preferential mitotic delay would increase the G2 cell population. However, we observed no shift in phase abundance when the first 3 mm of the meristem of stressed plants was compared with the control, although water stress did reduce the kinase activity in this segment and was earlier reported to reduce mitotic activity. The unchanged phase abundance therefore indicates that a mild water stress affected both G1 and G2 control points of the cell cycle in the basal part of the meristem. There is precedent for response at either control point since many plant cells arrest in G1 phase when differentiating, but under stress cells can alternatively arrest in G2 phase and can upon stimulation re-enter the cell cycle from either phase (Van't Hof, 1974, 1985; Bergounioux et al., 1988). The potential for arrest at a G2 control point is supported by the homogenous arrest of tobacco cells in late G2 phase when exposed to auxin without cytokinin (Zhang et al., 1996).

A control acting to prevent progress from G1 phase under stress was detected in cells at the distal margin of the meristem, where G1 phase cells increased from 62 to 90% in the 3- to 6-mm region after 48 h of stress (Fig. 8). Arrest in G1 phase is a component of normal leaf development and occurs as cells cease proliferation and switch to differentiation. Stress caused this to occur in cells nearer the base of the meristem. Both stressed and unstressed leaves showed a gradient of G1-phase cells increasing from 50% at the base to 100% in the cell-differentiation zone, but under stress a greater percentage of G1-phase cells was found in the 3- to 6-mm region. Inhibition of mitotic initiation has been detected in pea roots subjected to severe osmotic stress (Bracale et al., 1997), but the speed with which Cdc2 activity declined was not investigated.

Speed of Response of Cdc2-Like Kinase Activity

To assess the speed with which stress would affect cell-cycle catalysts, we measured an activity denoted as “Cdc2-like.” There may have been a contribution from Cdc2 variants, but the measured activity in the p13suc1 affinity-purified fraction was predominantly the mitotically active form of Cdc2, since activity of this enzyme is 4 times higher at mitosis than at other times in the cell cycle of plants (John et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 1996) and other organisms (for review, see Nurse, 1990; Stern and Nurse, 1996). We cannot eliminate the possibility of a minor contribution from variants of Cdc2, but activity from such variants has not yet been demonstrated unequivocally in plants. When assayed in animal cells with the H1 histone substrate used here (Tsai et al., 1991), activity from variants was at a low level compared with Cdc2 kinase.

The early decline in the Cdc2-like kinase activity (Fig. 6) indicates that the activation of the enzyme was directly affected by stress and is not consistent with the alternative possibility that slower cell growth might have slowed cell-cycle progress, leading to subsequent reduction in the number of cells approaching mitosis. This possibility must be seriously evaluated because a growth-dependent cell-cycle control point in the G1 phase has been detected in all eukaryotes studied. This control point is termed “start” in yeasts and “restriction point” in animal cells (Jagadish et al., 1977; Pardee, 1989), and an equivalent control point has been detected in unicellular green plants (Donnan and John, 1983; John et al., 1989). Given that the cell population is asynchronous, the decline in mitotic Cdc2 activity developed too rapidly (Fig. 4) to have feasibly resulted from slowed progression from the G1 phase, which would follow a lag equal to the minimum time required to progress from the late G1 control point to mitosis.

The length of the cell cycle of mesophyll cells in cereal leaves has been estimated at about 12 h (MacAdam et al., 1989); therefore, the lag could be approximately 6 h. Only after this time would cells that were in G1 at the time stress was imposed begin to be detected as failing to reach prophase and develop fully active kinase. The observed response (Fig. 6) was very different from this pattern; the response of the kinase activity to mild water stress began early and was completed rapidly. Within 3 h, activity in the 3- to 6-mm segment of stressed plants had declined by nearly 50%. To reinforce this argument, it is possible that the length of the cell cycle in wheat mesophyll cells may be greater than 12 h. The value of 12 h is for tall fescue (MacAdam et al., 1989); mesophyll cell-cycle length has not been assessed in wheat leaves, but epidermal cells of wheat were estimated to have a minimum cell-cycle length of 19 h (Beemster et al., 1997). If mesophyll and epidermal cells of wheat have the same cell-cycle length, then it is even less likely that the decline in Cdc2 activity detected here is merely due to a slowed progression from the G1 phase. We conclude that stress affected the Cdc2 kinase activity.

Activation State of Cd2-Like Kinase

Inactivation of the kinase by stress within 3 h was associated with an increase in the proportion of Tyr-phosphorylated protein, whereas the amount of protein remained constant. This change in phosphorylation state is consistent with the operation of a control during G2 phase that has been intensively studied in yeast and animal cells, in which mitotic activation of Cdc2 depends on the relative activities of inhibitory protein-Tyr kinases, especially Wee1 kinase, and the activating Cdc25 protein Tyr-phosphatase (Russell and Nurse, 1986, 1987; Millar et al., 1991; for review, see Norbury and Nurse, 1992; Lew and Kornbluth, 1996). In plant cells control of Cdc2 kinase activity by Tyr phosphorylation has also been detected at the initiation of mitosis, when increasing activity correlates with declining content of phospho-Tyr in the protein and with declining capacity for activation of isolated enzyme in vitro with purified Cdc25 enzyme (Zhang et al., 1996). Furthermore, a rate-limiting contribution of Cdc2 enzyme activity in mitosis is indicated by the ability of microinjected plant mitotic kinase to accelerate the prophase events of chromatin condensation: disassembly of the preprophase band and nuclear envelope breakdown (Hush et al., 1996).

The early response to water stress, a decrease in Cdc2-kinase activity within 3 h, must have derived largely from cells in prophase and metaphase, since these contain the most active forms of Cdc2 (Stern and Nurse, 1996; Zhang et al., 1996) and therefore contribute most of the activity in extracts from asynchronous meristems. In this early response the increase in Cdc2 phospho-Tyr and the decrease in Cdc2 activity indicate that the balance of kinase and phosphatase activities that control Cdc2 Tyr phosphorylation is responsive to stress in the plant. The inhibition of Cdc2 was reflected in an increased incidence of G2 phase cells, but as stress continued division was eventually completed, and by 48 h cells had accumulated in G1 phase. There was evidence that low activity of Cdc2 kinase in cells that arrested G1 phase arose from means other than Tyr phosphorylation, since levels of Cdc2 phospho-Tyr were low. This is consistent with evidence in other taxa that during G1 phase, Cdc2 phospho-Tyr is low or absent (Norbury and Nurse, 1992; Stern and Nurse, 1996); therefore, low activity derives from other mechanisms such as limiting G1 cyclin level (Sherr, 1996). However, the rapid inhibition of Cdc2 by Tyr phosphorylation is seen to contribute a fast-acting stress response and indicates that this control, which has been found to be important as a mitotic checkpoint mechanism in all eukaryotes (Nurse, 1994), is also caused by stress in the plant.

Mitotic Progression

A block to prophase is implied by the decline in Cdc2-like kinase activity that we observed under water stress, and there is direct evidence that plant cells do control cell-cycle progress at prophase. Extensive microscopic observation of live plant cells (Hepler, 1985) has revealed that they spend a prolonged but variable time (approximately 2 h) progressing through prophase, as seen by progressively increasing chromatin condensation. However, cells can spontaneously slow or reverse prophase right up to the time of nuclear envelope breakdown (Cleary et al., 1992; Hush et al., 1996). In the microscope-based experimental systems, physiological signals that can cause reversal of progress in prophase have not been investigated, but the present observations that water stress can reduce the activity of Cdc2 enzyme that drives prophase imply that in the intact plant stress can provide such a signal.

Model for Cell-Cycle Control in Water-Stressed Plants

Plants monitor the availability of water (for review, see Davies and Zhang, 1991; Munns and Sharp, 1993), and it is likely that a signaling pathway exists that integrates environmental stress with the control of cell division. Plant hormones have long been postulated as cell-division regulators during developmental and environmental responses (for review, see Evans, 1984; Munns and Sharp, 1993). The availability of water may be indicated by root-derived signals that are transmitted to leaves and affect leaf growth (Passioura, 1988; Davies and Zhang, 1991; Munns and Sharp, 1993). The process by which low soil water potential affects cell division in leaves is not known. It is possible that the water status of the dividing cells is altered, but no measurement of turgor of the dividing cells in leaves has been attempted, and no direct relation between water status and enzyme activity has been discovered. More likely is an altered hormonal balance influenced either by the water status of those cells or by a signal conveyed from roots to shoots.

Exogenous ABA application at high concentrations can reduce mitotic activity in roots (Robertson et al., 1990b; Müller et al., 1994), but this does not prove that endogenous ABA regulates cell-cycle progression. The effects of applied ABA on the proportion of cells in G1 and G2 phase are inconsistent. Applied ABA lengthened the phase of G2 relative to G1 in maize roots (Müller et al., 1994) but not in pea roots (Bracale et al., 1997). The latter study included a water-stress treatment that did lengthen the G2 phase relative to G1, but the stress was a very severe one (0.5 m mannitol). To our knowledge, the effects of exogenous application of ABA on cell-cycle progression in leaves has not been examined. A decreased supply of cytokinins from roots to leaves could conceivably control cell division in leaves of water-stressed plants, although there is no strong evidence to date (for review, see Munns and Cramer, 1996).

Unresolved also is the mechanism by which a root signal impinges on Cdc2 activity. In plant cells auxins are essential in promoting progress through the cell cycle, but cytokinins are most stringently required at the initiation of mitosis (Zhang et al., 1996). The signal could act directly on kinase or phosphatase modifiers of the Cdc2 enzyme but, alternatively, could act through a shift in general physiology related to growth rate. Additionally, if plants resemble metazoa in having a specific Cdc2 variant that is dedicated to S-phase events and is under the control of inhibitory Tyr phosphorylation, this phosphorylation could also underlie the accompanying decline in G1-/S-phase progression. We are currently unable to test this because kinase recovered by p13suc1 affinity is predominantly Cdc2 protein.

In fission yeast the growth rate clearly influences the timing of mitosis and, although the metabolites involved have not been identified, the mechanism is based on altered timing of Tyr phosphorylation in Cdc2 kinase (Russell and Nurse, 1986, 1987; Moreno et al., 1990; Lew and Kornbluth, 1996; Sveiczer et al., 1996). The requirement for cytokinin in plant cell division can be entirely met by expression of the Cdc2 Tyr-phosphatase Cdc25 (K. Zhang, L. Deiderich, F.J. Sek, P.J. Larkin, and P.C.L. John, unpublished observations), and the same Cdc2 phosphorylation is seen to occur under stress in the current study. However, it has not yet been tested whether this effect occurs solely through a mechanism that can be reversed by Cdc25 activity. A similar phosphorylation mechanism in wheat could account for the decline in mitosis.

Our model for the effect of mild water stress on leaf growth is that stress affects the cell cycle at control points in G1 phase and at late G2 phase. We propose that water stress induces a signal that increases the phosphorylation of Tyr at the active site of Cdc2 kinase and that this results in a predominance of the inactive form of the enzyme, with consequent inhibition of progression into mitosis, which is dependent on high activity of the enzyme. Since there is no long-term accumulation of cells in G2 phase, we deduce that there is also a slowing of progress from the G1 phase to the G2 phase, and in cells at the distal margin of the meristem this accumulation of cells in G1 phase accentuates a switch to cell differentiation that reduces meristem size.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. K. Zhang for advice and assistance in measuring Cdc2-phospho-Tyr, Drs. W. Silk and H. Skinner for helpful discussions, Dr. M. Westgate for assistance with psychrometry, and Dr. C. Wenzel for advice concerning microscopy.

Abbreviations:

- CDK

cyclin-dependent protein kinase enzyme

- p13suc1

13-kD universal mitotic protein with affinity for Cdc2 binding in vitro

Footnotes

This research was funded by the Cooperative Research Centre for Plant Science, Canberra, Australia.

LITERATURE CITED

- Beemster GTS, Masle J, Williamson RE, Farquhar GD. Effects of soil resistance to root penetration on leaf expansion in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): kinematic analysis of leaf elongation. J Exp Bot. 1997;47:1663–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Haj-Salah H, Tardieu F. Temperature affects expansion rate of maize leaves without change in spatial distribution of cell length. Analysis of the coordination between cell division and cell expansion. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:861–870. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.3.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergounioux C, Perennes C, Hemerly AS, Qin LX, Sarda C, Inzé D, Gadal P. Relation between protoplast division, cell-cycle stage and nuclear chromatin structure. Protoplasma. 1988;142:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bitonti MB, Ferraro F, Floris C, Innocenti AM. Response of meristematic cells to osmotic stress in Triticum durum. Biochem Physiol Pflanz. 1991;187:453–457. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JS, Knipling EB. Isopiestic technique for measuring leaf water potentials with a thermocouple psychrometer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;54:1044–1051. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracale M, Levi M, Savini C, Dicorato W, Galli MG. Water deficit in pea root tips: effects on the cell cycle and on the production of dehydrin-like proteins. Ann Bot. 1997;79:593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Brizuela L, Draetta G, Beach D. p13suc1 acts in the fission yeast cell cycle as a component of the p34cdc2 protein kinase. EMBO J. 1987;6:3507–3514. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary AL, Gunning BES, Wasteneys GO, Hepler PK. Microtubule and F-actin dynamics at the division site in living Tradescantia stamen hair cells. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:977–988. [Google Scholar]

- Clough BF, Milthorpe FL. Effects of water deficit on leaf development in tobacco. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1975;2:291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer GR, Bowman DC. Kinetics of maize leaf elongation. I. Increased yield threshold limits short-term, steady-state elongation rates after exposure to salinity. J Exp Bot. 1991;42:1417–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Davies WJ, Zhang J. Root signals and the regulation of growth and development of plants in drying soil. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Doerner PW. Cell cycle regulation in plants. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:823–827. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.3.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner PW, Jorgensen J-E, You R, Stepphun J, Lamb C. Control of root growth and development by cyclin expression. Nature. 1996;380:520–523. doi: 10.1038/380520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnan L, John PCL. Cell cycle control by timer and sizer in Chlamydomonas. Nature. 1983;304:630–633. doi: 10.1038/304630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand JL, Onillon B, Schnyder H, Rademacher I. Drought effects on cellular and spatial parameters of leaf growth in tall fescue. J Exp Bot. 1995;46:1147–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman L, Loy JB. Regulation of cell division in the subapical shoot meristem of dwarf watermelon seedlings by gibberellic acid and polyethylene glycol 4000. J Plant Growth Regul. 1987;5:140–161. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott JA, Nurse P. The cell cycle and suc1: from structure to function? Structure. 1995;5:321–325. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans ML. Functions of hormones at the cellular level of organization. In: Scott TK, editor. Hormonal Regulation of Development. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, New Series, Vol. 10. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1984. pp. 22–79. [Google Scholar]

- Foard DE, Haber AH. Anatomic studies of gamma-irradiated wheat growing without cell division. Am J Bot. 1961;48:438–446. [Google Scholar]

- Gorst J, Sek FJ, John PCL. Levels of p34cdc2-like protein in dividing, differentiating and dedifferentiating cells of carrot. Planta. 1991;185:304–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00201048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayles J, Nurse P. A pre-start checkpoint preventing mitosis in fission yeast acts independently of p34cdc2 tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1995;14:2760–2771. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemerly A, Engler JA, Bergounioux C, Van Montagu M, Engler G, Inzé D, Ferriera P. Dominant negative mutants of the Cdc2 kinase uncouple cell division from iterative plant development. EMBO J. 1995;14:3925–3936. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemerly AS, Ferriera P, Engler J de A, Van Montegue M, Engler G, Inzé D (1993) cdc2a expression in Arabidopsis is linked with competence for cell division. Plant Cell 5: 1711–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hepler PK. Calcium restriction prolongs metaphase in dividing Tradescantia stamen hair cells. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1363–1368. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.5.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Sek FJ, John PCL. Nuclear concentration and mitotic dispersion of the essential cell cycle protein p13suc1, examined in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2176–2180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pay HA, Gyorgyey J, Bako L, Newmeth K, Borge L, Schweyen R, Hirt J, Heberle-Bors E, Dudits D. Complementation of a yeast cell cycle mutant by an alfalfa cDNA encoding a protein kinase homologous to p34cdc2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1636–1640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hush JM, Wu L, John PCL, Hepler LH, Hepler PK. Plant mitosis promoting factor disassembles the microtubule preprophase band and accelerates prophase progression in Tradescantia. Cell Biol Int. 1996;20:275–287. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadish MN, Lorinez A, Carter BLA. Cell size and cell division in yeast cultured at different growth rates. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1977;2:235–237. [Google Scholar]

- John PCL. The plant cell cycle: conserved and unique features in mitotic control. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 1996;2:59–72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5873-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John PCL, Sek FJ, Carmichael JP, McCurdy DW. p34cdc2 homologue level, cell division, phytohormone responsiveness and cell differentiation in wheat leaves. J Cell Sci. 1990;97:627–630. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John PCL, Sek FJ, Hayles J. Association of the plant p34cdc2-like protein with p13suc1: implications for control of cell division cycles in plants. Protoplasma. 1991;161:70–74. [Google Scholar]

- John PCL, Sek FJ, Lee MG. A homologue of the cell cycle control protein p34cdc2 participates in the cell division cycle of Chlamydomonas and a similar protein is detectable in higher plants and remote taxa. Plant Cell. 1989;1:1185–1193. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.12.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John PCL, Zhang K, Dong C. A p34cdc2-based cell cycle: its significance in monocotyledonous, dicotyledonous and unicelluar plants. In: Ormrod JC, Francis D, editors. Molecular and Cell Biology of the Plant Cell Cycle. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993. pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jung G, Wernicke W. Cell shaping and microtubules in developing mesophyll of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Protoplasma. 1990;153:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lecoeur J, Wery J, Turc O, Tardieu F. Expansion of pea leaves subjected to short water deficit: cell number and cell size are sensitive to stress at different periods of leaf development. J Exp Bot. 1995;46:1093–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Nurse P. Complementation used to clone a homologue of the fission yeast cell cycle control gene cdc2. Nature. 1987;327:31–35. doi: 10.1038/327031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew DJ, Kornbluth S. Regulatory roles of cyclin dependent kinase phosphorylation in cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:795–804. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAdam JW, Volenec JJ, Nelson CJ. Effects of nitrogen on mesophyll cell division and epidermal cell elongation in tall fescue leaf blades. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:549–556. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.2.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez MC, Jorgensen J-E, Lawton MA, Lamb CJ, Doerner PW. Spatial pattern of cdc2 expression in relation to meristem activity and cell proliferation during plant development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7360–7364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar JBA, McGowan CH, Lenaers G, Johns R, Russell P. p80cdc25 mitotic inducer is the tyrosine phosphatase that activates p34Cdc2 kinase in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1991;10:4301–4309. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Nurse P, Russell P. Regulation of mitosis by cyclic accumulation of p80cdc25 mitotic inducer in fission yeast. Nature. 1990;344:549–552. doi: 10.1038/344549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller ML, Barlow PW, Pilet P-E. Effect of abscisic acid on the cell cycle in the growing maize root. Planta. 1994;195:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Munns R, Cramer GR. Is coordination of leaf and root growth mediated by abscisic acid? Opinion. Plant Soil. 1996;185:33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Munns R, Sharp RE. Involvement of abscisic acid in controlling plant growth in soils of low water potential. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1993;20:425–437. [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K. Putting the cell cycle in order. Science. 1996;274:1643–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Cyclin-dependent protein kinases; key regulators of the eukaryotic cell cycle. Bioessays. 1995;17:471–480. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbury C, Nurse P. Animal cell cycles and their control. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:441–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse P. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature. 1990;344:503–508. doi: 10.1038/344503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse P. Ordering S phase and M phase in the cell cycle. Cell. 1994;79:547–550. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse P, Bisset Y. Gene required in G1 for commitment to cell cycle and in G2 for control of mitosis in fission yeast. Nature. 1981;292:558–560. doi: 10.1038/292558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee AB. G1 events and regulation of cell proliferation. Science. 1989;246:603–608. doi: 10.1126/science.2683075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passioura JB. Root signals control leaf expansion in wheat seedlings growing in drying soil. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1988;15:687–693. [Google Scholar]

- Randall HC, Sinclair TR. Sensitivity of soybean leaf development to water deficits. Plant Cell Environ. 1988;11:835–839. [Google Scholar]

- Reed SI, Wittenberg C. Mitotic role for the CDC28 protein kinase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5697–5701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JM, Hubick KT, Yeung EC, Reid DM. Developmental responses to drought and abscisic acid in sunflower roots. 1. Root growth, apical anatomy, and osmotic adjustment. J Exp Bot. 1990a;41:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JM, Yeung EC, Reid DM, Hubick KT. Developmental responses to drought and abscisic acid in sunflower roots. 2. Mitotic activity. J Exp Bot. 1990b;41:339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Russell P, Nurse P. cdc25 functions as an inducer in the mitotic control of fission yeast. Cell. 1986;45:145–153. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell P, Nurse P. Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1, a gene encoding a protein kinase homolog. Cell. 1987;49:559–567. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks MM, Silk WK, Burman P. Effect of water stress on cortical cell division rates within the apical meristem of primary roots of maize. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:519–527. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.2.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp RE, Silk WK, Hsiao TC. Growth of the maize primary root at low water potentials. I. Spatial distribution of expansive growth. Plant Physiol. 1988;87:50–57. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk WK. Steady form from changing cells. Int J Plant Sci. 1992;153:S49–S58. [Google Scholar]

- Spollen WG, Nelson CJ. Response of fructan to water deficit in growing leaves of tall fescue. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:329–336. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.1.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern B, Nurse P. A quantitative model for the cdc2 control of S phase and mitosis in fission yeast. Trends Genet. 1996;12:345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveiczer A, Novak B, Mitchison JM. The size control of fission yeast revisited. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2947–2957. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.12.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai L-H, Harlowe E, Meyerson M. Isolation of the human cdk2 gene that encodes the cyclin A- and adenovirus E1A-associated p33 kinase. Nature. 1991;353:174–177. doi: 10.1038/353174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van't Hof J (1974) Control of the cell cycle in higher plants. In GM Padilla, IL Cameron, A Zimmerman, eds, Cell Cycle Control. Academic Press, New York, pp 77–85

- Van't Hof J. Control points within the cell cycle. Soc Exp Biol Semin Ser. 1985;26:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Volenec JJ, Nelson CJ. Cell dynamics in leaf meristems of contrasting tall fescue genotypes. Crop Sci. 1981;21:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Yee VF, Rost TL. Polyethylene glycol induced water stress in Vicia faba seedlings: cell division, DNA synthesis and a possible role for cotyledons. Cytologia. 1982;47:615–624. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Letham DSL, John PCL. Cytokinin controls the cell cycle at mitosis by stimulating the tyrosine dephosphorylation and activation of p34cdc2-like H1 histone kinase. Planta. 1996;200:2–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00196642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]