Abstract

Background:

The aim of our clinical trial was to assess the efficacy of 0.1% turmeric mouthwash as an anti-plaque agent and its effect on gingival inflammation and to compare it with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate by evaluating the effect on plaque and gingival inflammation and on microbial load.

Materials and Methods:

60 subjects, 15 years and above, with mild to moderate gingivitis were recruited. Study population was divided into two groups. Group A-30 subjects were advised chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash. Group B-30 subjects were advised experimental (turmeric) mouthwash. Both the groups were advised to use 10 ml of mouthwash with equal dilution of water for 1 min twice a day 30 min after brushing. Parameters were recorded for plaque and gingival index at day 0, on 14 th day, and 21 st day. Subjective and objective criteria were assessed after 14th day and 21st day. The N-benzoyl-l-arginine-p- nitroanilide (BAPNA) assay was used to analyze trypsin like activity of red complex microorganisms.

Results:

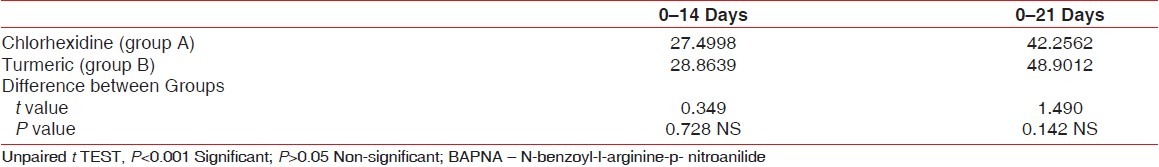

On comparison between chlorhexidine and turmeric mouthwash, percentage reduction of the Plaque Index between 0 and 21 st day were 64.207 and 69.072, respectively (P=0.112), percentage reduction of Gingival Index between 0 and 21st day were 61.150 and 62.545 respectively (P=0.595) and percentage reduction of BAPNA values between 0 and 21st day were 42.256 and 48.901 respectively (P=0.142).

Conclusion:

Chlorhexidine gluconate as well as turmeric mouthwash can be effectively used as an adjunct to mechanical plaque control in prevention of plaque and gingivitis. Both the mouthwashes have comparable anti-plaque, anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial properties.

Keywords: BAPNA, Chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash, turmeric mouthwash

INTRODUCTION

Dental plaque has been proved by extensive research to be a paramount factor in initiation and progression of gingival and periodontal diseases.[1] A direct relationship has been demonstrated between plaque levels and the severity of gingivitis. The most rational methodology toward the prevention of periodontal diseases would be regular, effective removal of plaque by the personal oral hygiene protocol. Procedures for plaque control include mechanical and chemical means. Mechanical means include brushing, flossing, use of interdental cleansing aids, and oral prophylaxis. These methods have proved to be very time consuming and their effectiveness would depend on skills and technique of the individual carrying out these procedures. Thus, chemical plaque control can be used as an adjunct to mechanical plaque control procedures.

Recently, a number of chemical agents have been advocated which are either available in a toothpaste/dentifrices or in the form of a mouthwash. Among them, chlorhexidine is regarded as gold standard in dentistry for the prevention of dental plaque. The various mouthwashes available today are having certain side effects and are also expensive. Chlorhexidine mouthwash though very effective also has certain side effects like brown discoloration of the teeth, oral mucosal erosion, and bitter taste.[2] Hence, there is a need of an alternative medicine that could provide a product already enmeshed within the traditional Indian set-up and is also safe and economical.

“AYURVEDA” (Ayu-life and Veda-science) system of Indian medicine has been used successfully for treating various systemic ailments. Turmeric, more commonly known as “HALDI”, in its various forms is a very auspicious element in many religious ceremonies in Hindu families. It is widely used as a household spice for various cuisines of the country. Turmeric possesses anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-microbial properties, along with its hepatoprotective, immunostimulant, antiseptic, antimutagenic, and many more properties.[3] It is for this concern that promotion of turmeric in dental terrain would prove beneficial.

Considering all above claims and facts, this study was carried out using the purest and soluble form of turmeric to test its anti-plaque and anti-inflammatory properties in the form of a mouthwash. Microbiological evaluation was carried out to prove the efficacy of experimental mouthwash.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

A total of 100 subjects of both the sexes visiting the Department of Periodontology, Bharati Vidyapeeth University Dental College and Hospital, Pune, were considered for the study. The patients who were invited to participate met the following inclusion criteria: (1) subjects of age 15 years and above; (2) subjects with mild to moderate gingivitis; (3) subjects having at least 20 erupted teeth. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of systemic diseases; (2)pregnant, lactating females; (3) history of any antibiotic therapy in past 3 months; (4) history of oral prophylaxis within 6 months previous to the study; (5) subjects with mouth breathing habit; (6) subjects using orthodontic and prosthodontic appliances; (7) subjects with deleterious habit like smoking.

Study design and clinical measurements

The clinical data was recorded in a case history proforma. The subjects were assessed for plaque and gingival inflammation by recording plaque index (Turesky-Gilmore-Glickman modification of the Quigley Hein 1970) and gingival index (Loe And Silness). After recording plaque index and gingival index thorough scaling and polishing was carried out to get subjects at the baseline. Instructions for maintenance of oral hygiene were given. No mouthwash was prescribed at this stage. Subjects were recalled after 1 month and they were assessed again for plaque and gingivitis.

Out of 100 subjects, 60 subjects with mild to moderate gingivitis were included in the study. Study population was divided into two groups. Group-A — 30 subjects were advised chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash. Group-B — 30 subjects were advised experimental (turmeric) mouthwash.

The preparation of above experimental mouthwash was carried out with help of Poona College of Pharmacy, Pune. Its composition was turmeric extract 0.1% (curcumin equivalent), eugenol 0.01%, and water q.s.

For a period of 21 days, both the groups were advised to use 10 ml of mouthwash with equal dilution of water for 1 min twice a day after 30 min of brushing. The parameters were recorded for plaque and gingival index at day 0, on 14th day, and 21st day. Subjective and objective criteria were assessed after 14th day and 21st day.

Subjective criteria

(1) Taste acceptability: 0-acceptable; 1-tolerable; 2- unacceptable; (2) Burning sensation: 0-absent; 1-present; (3) Dryness/soreness: 0-absent; 1-present.

Objective criteria

(1) Ulcer formation: 0-absent; 1-present; (2) Staining of teeth: 0 - absent; 1-present; (3) Staining of tongue: 0-absent; 1-present; (4) Allergy: 0-absent; 1-present.

Microbial evaluation

N-benzoyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide assay

For microbiological evaluation, a total of 60 subjects (30 from each group) were selected. The supra-gingival plaque samples were collected from the buccal surfaces of tooth numbers 16 and 36 with help of sterile Gracey curette on 0 and 21st day. The supra-gingival plaque samples were carried in transport media-Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) for microbiological study. The plaque samples were assessed for estimating trypsin like protease activity of the “Red Complex” microorganisms namely Tannerella forsythia, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Treponema denticola.[4]

The plaque collected was placed in preweighed coded microcentrifuge tubes. An amount of 1 ml of a solution containing the enzyme substrate (N-benzoyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide, BAPNA; Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was then added to the tubes. This suspension was vortexed and then placed in an ultrasound bath on ice for 10 min with 2-s cycles and 2-s intervals at 17 W using a 100 W ultrasonic processor. After 17 h of incubation at 37°C, the reaction was stopped with ice and by the addition of 100 ml of glacial acetic acid. The absorbance was read at 405 nm. The results were given in nanomoles of product per minute per milligram of dental plaque wet weight.[5]

Statistical analysis

Changes from baseline to different time intervals in various clinical parameters were analyzed by the paired t-test (Intragroup comparisons). Intergroup comparisons of post-treatment changes were analyzed by the unpaired t-test. A P<0.05 was considered as a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Total 60 subjects were finally included for statistical evaluation of clinical study as they could report for all the visits: 30 subjects from the chlorhexidine group and 30 subjects from the turmeric group.

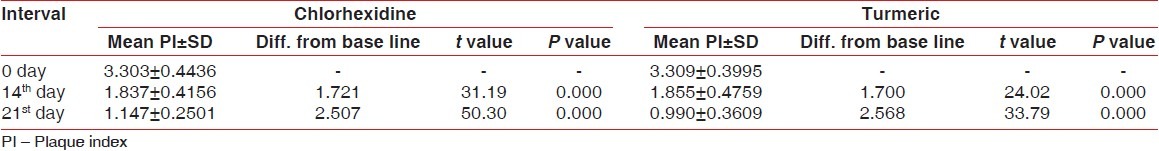

At baseline, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups with regards to plaque index and gingival index [Tables 1–4].

Table 1.

Plaque index

Table 4.

Percentage reduction of gingival index

Plaque index

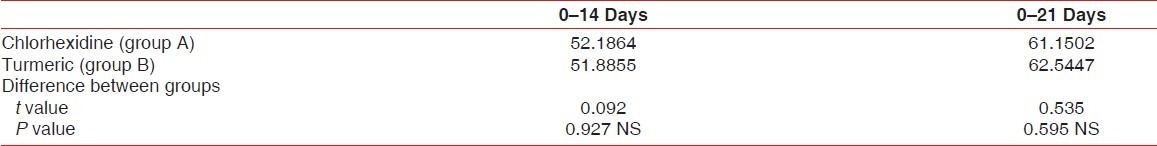

The Plaque index (PI) was reduced during the study in both groups, but no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups [Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1].

Table 2.

Percentage reduction of plaque index

Figure 1.

Plaque index (PI) over the period; comparison between the groups

Chlorhexidine mothwash (Group A)

The mean PI was 3.303±0.444 at day 0, 1.837±0.416 at day 14, and 1.147±0.250 at day 21 [Table 1].

The difference of mean plaque index between 0 and 14th day was 1.721 (statistically significant P<0.001) and between 0 and 21st day was 2.507 (statistically significant P<0.001) [Table 1].

Turmeric mouthwash (group B)

The mean PI value was 3.309±0.399 at day 0, 1.855±0.475 at day 14, and 0.990±0.0.361 at day 21 [Table 1].

The difference of mean plaque index between 0 and 14 th day was 1.700 (statistically significant P<0.001) and between 0 and 21 st day was 2.568 (statistically significant P<0.001) [Table 1].

On comparison between chlorhexidine and turmeric mouthwash, the percentage reduction of PI between 0 and 14th day were 43.760±10.576 and 43.776±11.321, respectively (P=0.995). The percentage reduction of PI between 0 and 21st day were 64.207±10.456 and 69.072±12.913 respectively (P=0.112) [Table 2].

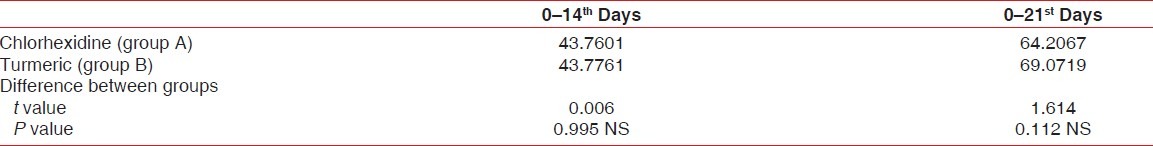

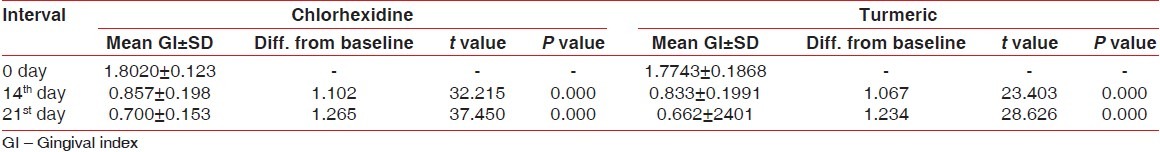

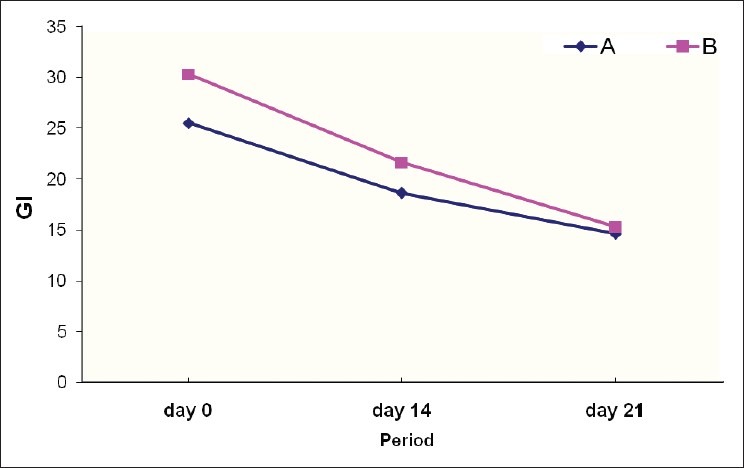

Gingival index

Gingival index was reduced during the study in both groups, but no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups [Tables 3 and 4, Figure 2].

Table 3.

Gingival index

Figure 2.

Gingival index (GI) over the period; comparison between the groups

Chlorhexidine mothwash (group A)

Mean GI was 1.802±.123 at day 0, 0.857±0.198 at day 14, and 0.700±0.153 at day 21 [Table 3].

The difference of mean gingival index between 0 and 14th day was 1.102 (statistically significant P<0.001) and between 0 and 21 st day was 1.265 (statistically significant P<0.001) [Table 3].

Turmeric mouthwash (group B)

The mean GI value was 1.774±0.187 at day 0, 0.833±0.199 at day 14, and 0.662±0.240 at day 21 [Table 3].

The difference of mean plaque index between 0 and 14th day was 1.067 (statistically significant P<0.001) and between 0 and 21 st day was 1.234 (statistically significant P<0.001) [Table 3].

On comparison between chlorhexidine and turmeric mouthwash, the percentage reduction of GI between 0 and 14 th day were 52.186±11.842 and 51.886±13.809, respectively (P=0.927). The percentage reduction of PI between 0-21st day were 61.150±8.300 and 62.545±11.796 respectively (P=0.595) [Table 4].

Microbial evaluation

N-benzoyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide assay

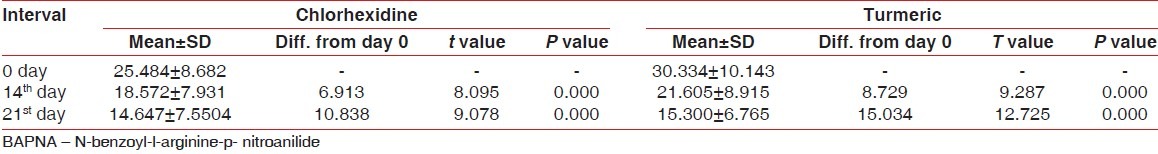

Tables 5 and 6 present the results of BAPNA at days 0, 14, and 21. Both groups, at 0,14th and 21st day, showed a statistically significant reduction of trypsin-like enzyme activity in supragingival biofilm, without a difference between the groups [Figure 3].

Table 5.

Values of BAPNA

Table 6.

Percentage reduction of BAPNA values

Figure 3.

BAPNA values over the period; comparison between the groups

Chlorhexidine mothwash (group A)

The mean BAPNA value was 25.484±8.682 nmoles/min/mg at day 0, 18.572±7.931 nanomoles/min/mg at day 14 and 14.647±7.550 nmoles/min/mg at day 21.

The difference of mean BAPNA values between 0 and 14th day was 6.913 (statistically significant P<0.001) and between 0 and 21 st day was 10.838 (statistically significant P<0.001) [Table 5].

Turmeric mouthwash (group B)

The mean BAPNA value was 30.334±10.143 nmoles/min/mg at day 0, 21.605±8.915 nmoles/min/mg at day 14 and 15.300±6.765 nmoles/min/mg at day 21 [Table 5].

The difference of mean BAPNA values between 0 and 14th day was 8.729 (statistically significant P<0.001) and between 0 and 21st day was 15.034 (statistically significant P<0.001) [Table 6].

DISCUSSION

Chlorhexidine has been regarded as a “gold” standard in dentistry for the prevention of plaque and gingivitis. Large reductions were found in plaque formation using chlorhexidine gluconate, applied topically or as a mouth rinse.[6–11] The results indicated that two daily mouth rinses with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate effectively prevented plaque formation. In our study, chlorhexidine mouthwash showed significant reduction in mean plaque score at 0,14th and 21st day from baseline similar to study by Loe.[6]

Our results related to turmeric are consistent with a study carried out by Bhandari[12] where an experimental mouthwash i.e., combination of four ayurvedic drugs (Beriberi Aristata, curcuma longa, Curcuma Amda, and Glycerrhiza ) was prescribed along with routine oral hygiene measures. Reduction in mean plaque index was observed from 0 to 21st day. In our study, similar results were obtained with subjects using experimental mouthwash i.e., turmeric mouthwash along with routine oral hygiene measures. This may be because of the anti-plaque effect of turmeric. A comparable anti-plaque effect was found with turmeric and chlorhexidine mouthwash in our study. This may be because of turmeric, which was in pure and completely water-soluble form, so the available concentration was more and it may also be because of its anti-plaque property. Significant plaque reduction from the baseline to day 14th and to day 21st was observed with both the mouthwashes.

Considering the anti- inflammatory effect of turmeric mouthwash, our results for the Gingival Index are consistent with the results of Bhandari Van der Weijden et al.[13] Grundemann et al.[10] , Leyes, et al.[11,12] A statistically significant reduction of gingival inflammation was observed in subjects using experimental mouthwash. In our study, the reduction in mean gingival score in subjects using turmeric mouthwash may be because of its anti-inflammatory property.

Arora[14] evaluated anti-inflammatory property of turmeric i.e., total petroleum ether extract of the rhizomes of turmeric and two of its constituents (fraction A and B) in rats and compared it with hydrocortisone acetate and phenylbutazone. The results showed significant reduction of inflammation (P<0.001) in all the groups. In our study, anti-inflammatory action of turmeric was evaluated on clinical parameters using the gingival index, which showed significant reduction. This suggests that turmeric has an anti-inflammatory property.

In studies carried out by Van der Weijden et al.[13] Grundemann et al.[10] , Leyes, et al.[11] significant reduction of gingival inflammation was observed in chlorhexidine mouthwash which is similar to the findings in our study. Taking into consideration all the findings of our study, it is clear that both the mouthwashes are equally effective in reducing the gingival inflammation.

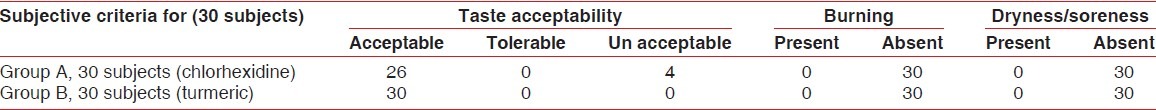

The turmeric mouthwash was acceptable in taste and was biocompatible. It has been observed in the present study from subjective and objective criteria [Tables 7 and 8] that bitter taste was experienced by four subjects using chlorhexidine mouthwash. Staining of tongue was observed in three subjects using turmeric mouthwash however it was temporary. Many other studies observed certain side effects with chlorhexidine mouthwash similar to our studies. (Lang et al.1988, Flotra et al. 1971, Leach 1977).[2] Thus, the results of our study show that the turmeric mouthwash is free of the side effects of bitter taste and staining which occur with the chlorhexidine mouthwash.

Table 7.

Subjective criteria

Table 8.

Objective criteria

Our clinical study was supported by the microbiological evaluation which strongly proved the efficacy of experimental mouthwash. The microbial evaluation was done by the BAPNA assay which quantitatively evaluates trypsin-like enzyme activity of important periodontal pathogens like T. forsythia, Treponema denticola, and P. gingivalis in the plaque sample (Syed, et al.).[4]

No studies have been carried out, to the best of our knowledge, comparing the effect of chlorhexidine or turmeric mouthwashes with the BAPNA assay. Other methods which are used for microbiological evaluation are culture methods, dark field microscopy, DNA Probes, immunological reagents, BANA assay, etc. The BANA (benzoyl-dl-arginine-naphthylamide) assay has the same principle as the BAPNA assay but is a qualitative test.

Ribeiro, et al.[5] determined the effect of mechanical supragingival plaque control on clinical and biochemical parameters of chronic periodontitis. The biochemical evaluation was done with the BAPNA test. The results showed a decrease from 51.44±20.78 to 38.64±12.34 (P=0.04). Similar reduction in BAPNA values were found in our study.

Drake et al.[15] studied the antibacterial effect of curcumin (turmeric). Bacterial colonies were inoculated into tryptic soya broth enriched cultures. The results of this study showed the curcumin inhibits the growth of C. gingivalis and P. melanogenica. In our study subjects using turmeric mouthwash showed similar significant reduction. This was comparable with the chlorhexidine group.

The findings of our study suggest that turmeric has got definite antimicrobial property. When studied microbiologically it was observed that reduction in mean BAPNA values (that permits the detection of microorganisms possessing trypsin-like enzymes such as T. forsythensis, Treponema denticola and P. gingivalis) was found to be similar in both the groups (Group-A and B) after 21 days. Thus it was found microbiologically that both the mouthwashes were equally effective.

From the overall results it can be concluded that turmeric mouthwash shows anti-plaque property comparable to chlorhexidine mouthwash. When effect on gingival inflammation was observed both the mouthwashes were found to be equally effective. When the subjective and objective criteria were evaluated it was observed that turmeric mouthwash shows better biocompatibility and acceptability by the subject. Microbiologically, both the mouthwashes were equally effective.

CONCLUSION

Based on the observations of our study, it can be concluded that chlorhexidine gluconate as well as turmeric mouthwash can be effectively used as an adjunct to mechanical plaque control in prevention of plaque and gingivitis. Both the mouthwashes have comparable anti-plaque, anti-inflammatory, and anti-microbial properties. Turmeric mouthwash was biocompatible and well accepted by all the subjects without side effects. Substantivity of turmeric mouthwash is required to be studied in the future.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fine HD. Chemical agents to prevent and regulate plaque development. Periodontol 2000. 1995;8:87–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1995.tb00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jan L. 4th ed. Blackwell Munksgaard; 2003. Textbook of Clinical Periodontology and Implantology Dentistry; p. 477. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivan Ross A. Chemical constituents, traditional and modern medicinal uses. Vol. 2. Tatowa, New Jersy: Humana press; 1999. Medicinal plant of the world Text book. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syed SA, Gusberti FA, Loesche WJ, Lang NP. Diagnostic potential of chromogenic substrates for rapid detection of bacterial enzymatic activity in health and disease associated periodontal plaques. J Periodontol Res. 1984;19:618–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1984.tb01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribeiro ED, Bittencourt S, Nociti-Junior FH, Sallum EA, Sallum AW, Casati MZ. The effect of one session of supragingival plaque control on clinical and biochemical parameters of chronic periodontitis. J Appl Oral Sci. 2005;13:275–9. doi: 10.1590/s1678-77572005000300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loe H, Schiott C. The effect of mouthrinse and topical application of chlorhexidine on the development of dentalplaque and gingivitis. J Periodontal Res. 1970;5:79–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1970.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindhe J, Hamp SE, Loe H, Schiott CR. Influence of topical applications of chlorhexidine on chronic gingivitis and gingival wound healing. Scand J Dent Res. 1970;78:471–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1970.tb02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst CP, Prockl K, Willershemsen B. The effectiveness and side effects of 0.1% chlorhexidine mouthrinse. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:443–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francetti L, del Fabbro M, Testori T, Weinstein RL. Chlorhexidine spray versus chlorhexidine mouthwash in the control of dental plaque after periodontal surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:425–30. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027006425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundenmann LJ, Timmerman MF, Ijserman Y, van der Velden U, van der Weijden GA. Reduction of stain, plaque and gingivitis by mouthrinsing with chlorhexidine and sodium perborate. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2002;109:225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leyes Borrajo JL, Garcia VL, Lopez CG, Rodriguez-Nuñez I, Garcia FM, Gallas TM, et al. Efficacy of chlorhexidine mouthrinses with and without alcohol: A clinical study. J Periodontol. 2002;73:317–21. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhandari H, Shankwalkar GB. Clinical assessment of action of combination of indigenous drugs on dental plaque, calculus and gingivitis. Dissertation submitted to the University of Bombay. 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Weijden GA, Timmer CJ, Timmerman MF, Reijerse E, Mantel MS, van der Velden U. The effect of herbal extract in an experimental mouthrinse on established plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:399–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora RB. Anti inflammatory studies on Curcuma Longa. Indian J Med Res. 1971;59:1289–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake D, Halt S, Schwartz J, et al. Effects of environmental agents on bacteria of the oral cavity. Clinical Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 2004 Seq no. 19. [Google Scholar]