Abstract

Objectives:

To assess oral hygiene status, oral hygiene practices and periodontal status among 14-17-year-old visually impaired, deaf and dumb, intellectually disabled and physically challenged and normal teenagers in the district of Nalgonda, South India.

Materials and Methods:

Seven hundred and fifty teenagers in the age group of 14-17 years, constituting visually impaired, deaf and dumb, intellectually disabled, physically challenged and normal teenagers, were studied. Oral hygiene status and periodontal status were assessed using clinical indices and compared.

Results:

Among the five groups chosen for the study, the intellectually disabled group had the highest plaque scores and poor oral hygiene. The visually impaired and deaf and dumb had better oral hygiene compared with other disability groups. Physically handicapped showed higher loss of attachment scores and deleterious and parafunctional habits. Normal teenagers had good oral hygiene and lower plaque scores. Oral health status relied basically on proper use of oral hygiene aids and training of the groups by their care takers.

Conclusion:

Disabled groups showed poor oral hygiene and higher incidence of periodontal disease, which may be attributed to the lack of coordination, understanding, physical disability or muscular limitations. Hence, more attention needs to be given to the dental needs of these individuals through ultimate, accurate and appropriate prevention, detection and treatment.

Keywords: Disabled children, oral health, oral hygiene, periodontal disease

INTRODUCTION

Health is “A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, rather than solely by an absence of disease or infirmity.”[1] Oral health and quality oral health care contribute to holistic health. It should be a right not a privilege. [ 2]

Handicap is the loss or limitation of opportunities to take part in the normal life of the community on an equal level with others due to physical and social barriers.[3] The barriers to oral health that people with disabilities experience will vary by age and the level of parental or social support received. These change throughout life, with particular problems associated with transitional periods.[3] Attitudes to oral health, oral hygiene and dental attendance and the relative value placed upon these factors must be viewed in the context of illness, disability, socioeconomic status and stresses imposed upon daily living for the individual, family and care takers.

Oral health may have a low priority in the context of these pressures and other disabilities, which are more life-threatening.[4] Hence, it requires a change in attitude and practice for parents/care takers to include oral health as part of routine care. Evidence confirms that uptake of screening services for people with learning disabilities are lower and that they have poor oral health when compared with the general population. Poor oral health may add an additional burden, whereas good oral health has holistic benefits in that it can improve general health, dignity and self-esteem, social integration and quality of life.[5]

In India, no single standard exists in order to evaluate disability. Different terms such as disabled, handicapped and crippled, physically challenged are used interchangeably. Nationwide surveys of oral condition of handicapped people are lacking. A higher proportion of untreated lesions in handicapped children compared with non-handicapped children has been documented throughout the world.[6] Hence, this study has attempted to assess the periodontal status and oral hygiene status among 14-17-year-old visually handicapped, intellectually disabled, deaf and dumb, physically challenged and normal teenagers in the district of Nalgonda in Andhra Pradesh.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 750 teenagers in the age group of 14-17 years were examined at five different educational institutions and five care homes in and around Nalgonda district of Andhra Pradesh. One hundred and fifty visually impaired, 150 intellectually disabled, 150 deaf and dumb and 150 physically handicapped were examined along with 150 normal healthy teenagers as the control group. The disabled teenagers were grouped based on the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.[1]

After obtaining consent from the caretaker or guardian, the oral hygiene status and periodontal status were assessed. All the teenagers were examined using a WHO questionnaire given in 1997, modified according to the study needs that included plaque index (Sillness and Loe),[6] simplified oral hygiene index (Greene and Vermillion)[6] and community periodontal index.[6] Teenagers from whom the proxy consent from the care takers could not be obtained and those suffering from other debilitating systemic conditions were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Board of the Kamineni Institute of Dental Sciences, Nalgonda.

The indices were recorded by three examiners who were calibrated prior to the study to reduce inter-examiner variability. The following clinical parameters were also compared between the teenagers of the five groups:

Disability and usage of dentrifice

Disability and usage of oral hygiene aids

Disability and frequency of tooth brushing

Disability and parafunctional habits

Disability and deleterious habits.

The mean scores were compared among the groups using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), Chi-square test and Tukey's HSD test.

RESULTS

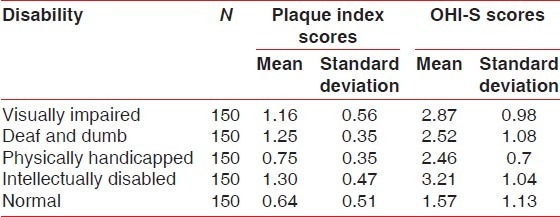

Table 1 shows the mean plaque index scores and OHI-S scores among the different disability groups. Among the groups, the intellectually disabled group had the highest mean plaque index score of 1.3±0.47, followed by deaf and dumb 1.25±0.35, visually impaired teenagers 1.16±0.56 and healthy teenagers 0.64±0.51. Among the groups, intellectually disabled had the highest mean OHI-S score of 3.21±1.04, followed by visually impaired 2.87±0.98 and deaf and dumb 2.52±1.08.

Table 1.

Mean plaque index and OHI-S scores among the different disability groups

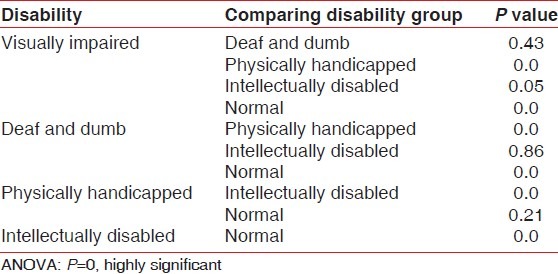

Table 2 compares the plaque index scores among different disability groups using Tukey HSD. The plaque index scores were significantly higher in the visually impaired when compared with normal, physically handicapped and intellectually disabled. Visually impaired teenagers showed no significant difference in plaque index scores when compared with deaf and dumb and deaf and dumb when compared with intellectually disabled.

Table 2.

Inter-group comparison of plaque index scores among different disability groups

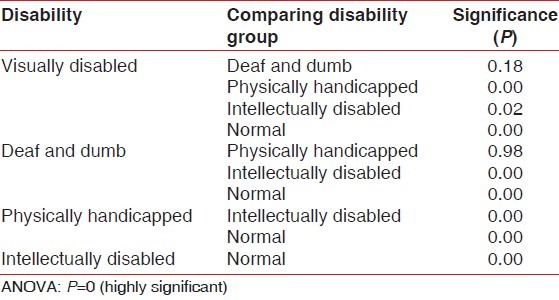

Table 3 compares the mean OHI-S scores among the different disability groups using Tukey HSD. The groups showed statistically significant difference in OHI-S scores, except for the deaf and dumb group, which showed no significant difference when compared with the physically handicapped group and visually disabled.

Table 3.

Inter-group comparison of mean OHI-S scores among different disability groups

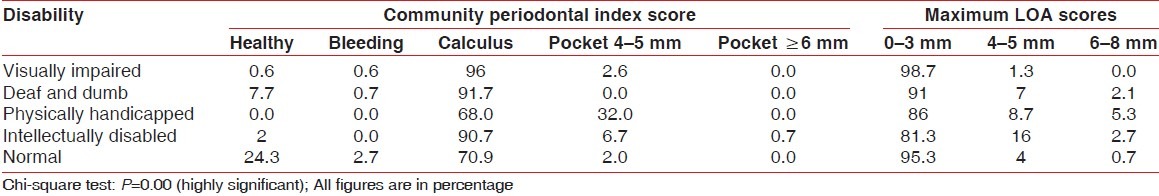

Table 4 shows the CPI and loss of attachment scores. Among the groups studied, visually impaired showed the highest calculus scores of 96%, followed by deaf and dumb, with scores of 91.7%. Pockets of 4-5 mm were highest in the physically handicapped with 32%, and 0.7% of intellectually disabled with pocket depth of 36 mm. Highest LOA of 6-8 mm was found in physically handicapped, with 5.3%, followed by 2.7% in intellectually disabled and LOA scores of 4.5 mm in 16% of the intellectually disabled and physically handicapped with 8.7%.

Table 4.

Mean CPI and loss of attachment scores among different disability groups

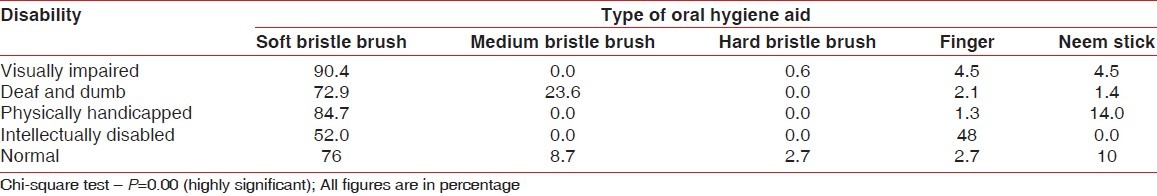

Table 5 shows the different oral hygiene aids among the disability groups. Use of finger as an oral hygiene aid was seen in 48% of the intellectually disabled group. The highest percentage of patients using soft bristle brush was seen in 90.4% in the visually impaired group, followed by the physically handicapped group with 84.7%; 14% of the physically handicapped group were found to be using neem stick.

Table 5.

Comparison of usage of different oral hygiene aids among disability groups

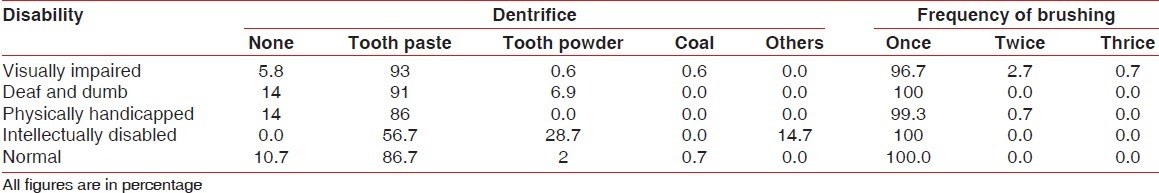

Table 6 shows the usage of dentifrice and frequency of brushing among different disability groups. Among the groups compared, the highest percentage of dentifrice used among all the groups was tooth paste. 28.7% of the intellectually disabled used tooth powder as a dentifrice. A comparison of the frequency of tooth brushing among the disability groups revealed that the maximum number of teenagers brushed once daily in the morning and only 2.7% of the normal teenagers brushed their teeth twice a day.

Table 6.

Usage of dentrifice and frequency of brushing among different disability groups

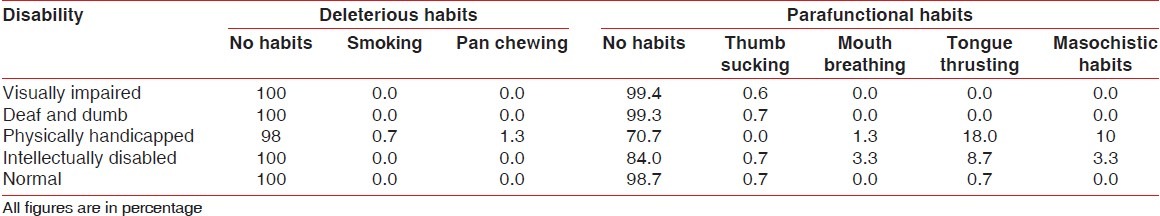

Table 7 lists out the deleterious habits and parafunctional habits among disability groups. Only 0.7% of the physically handicapped had smoking habit and 1.3% had pan chewing habit. Eighteen percent of the physically handicapped had tongue thrusting habit and 10% had masochistic habits. Tongue thrusting habit was also noticed in 8.7% of the intellectually disabled teenagers.

Table 7.

Deleterious and parafunctional habits among disability groups

DISCUSSION

The disabled and handicapped form a substantial section of the community. The effect of disabling conditions are many and varied, but one of the most common effects is inability to maintain oral health.[7] The three principal components - impairment, disability and handicap - would operate independently, with impairment addressing impact on the body; disability to impact on the person; and handicap to impact on the person interacting with the environment.[8]

In disabled individuals, the process of developing gingival/periodontal diseases does not differ from non-disabled individuals. Plaque control and gingival and periodontal health are frequently poor compared with children of same age without handicaps.[9] The main factor related to gingival/periodontal problems in disabled individuals is the inadequacy of the plaque removal from the teeth.

The present study showed that mean plaque index scores were very high among the visually impaired group. On evaluation of oral hygiene practices, most of the teenagers used soft tooth brush and tooth paste. On comparison, OHI-S scores were found to be high among the visually impaired and deaf and dumb. They also showed the highest incidence of calculus accumulation. Anaise[10] concluded that partially blind students had a lower mean plaque index value than the totally blind students. Dinesh[5] and Azrina[11] concluded that disabled children experience greater challenges to proper oral hygiene and health care, often due to a lack of basic manual skills and intellectual abilities that precludes adequate practices, such as tooth brushing. The degree of periodontal disease among this group was higher because of the difficulty to maintain oral hygiene without visual feedback of seeing whether plaque had been removed or gums were bleeding while brushing.

Physically handicapped showed moderate mean plaque levels. Thirty-two percent among them showed a pocket depth of 4-5 mm, and 8.7% showed loss of attachment of 4-5 mm. The higher plaque score and incidence of periodontal disease can be attributed to lack of manual dexterity, which was in accordance with studies conducted by Klaus Pieper.[11] On the contrary, Shaw et al.[12] assessed manual dexterity in their study, and showed that although periodontal health was poor among the group, it was not correlated with manual dexterity.

The intellectually disabled group studied showed the highest mean plaque index scores and poor oral hygiene. Forty-eight percent among them were using finger as an oral hygiene aid. Sixteen percent among them showed loss of attachment of 4-5 mm. Mitsea[13] concluded that the treatment needs regarding both dentitions are extremely high, especially in individuals with mental retardation, and the highest rate of malocclusion is observed in individuals with cerebral palsy. Fatima et al.,[14] Al-Qahtani et al.,[15] Akpata et al.[16] Kumar et al.[17] and Manish et al.[18] in their studies highlighted that more attention has to be given to the dental needs of these individuals.

Among all the groups studied, healthy teenagers showed the least plaque scores and good oral hygiene. The maximum number of teenagers brushed once daily, and 2.7% brushed their teeth twice a day.

As the study has shown, greater reliance must be placed on tactile stimuli, such as teaching the visually impaired person to detect plaque with the tongue. Therefore, to educate visually impaired people, a clear verbal instructions acting out by touch have to be used.[15] Hearing impaired showed lack of communication as a major hindrance for their access to oral health. This group depended upon their teachers trained in special education.[19] Motor coordination problems and muscular limitation in neuromuscularly disabled individuals along with the difficulty in understanding the importance of oral hygiene in mentally disabled individuals have resulted in the progression of inflammatory diseases.[14] More attention needs to be given to the dental needs of individuals with intellectual disability, through accurate and appropriate prevention, detection and treatment of these conditions.[20]

Frail, disabled persons have limited access to dental care, which is compounded by a shortage of dental professionals who are willing to treat these populations.[21] Increasing number of people with mental retardation no longer live in institutions, and they are dependent on dentists for care. Increasing dental school training and continuing education programmes are needed to meet this end.[22] School teachers need proper training and practical support from dentists experienced in dental health to train these disabled persons. Chemical plaque control has been recommended as an alternative and adjunctive to mechanical plaque control in these special patient groups.

The true measure of a society lies in the way it treats its older, handicapped and disadvantaged citizens. If good oral health is to become a reality in the future for people with special needs, it is essential that people in daily contact with the individuals become involved in oral care. With increasing number of people with special needs, the oral health fraternity should actively involve with other parts of the community to bring about general and social wellbeing and benefit them with sustained lifetime oral health.[23,24]

In conclusion, teenagers belonging to the disability groups inculcate habits under the influence of surroundings, capability and interest of parents and caretakers. The impairment leads to disability, and deprivation of these groups resulted in poor oral hygiene and subsequent periodontal diseases. A holistic approach is needed from periodontists and other specialists to achieve satisfactory periodontal health in these subjects. Constant motivation of the parent and caretakers to comply for the demands of the treatment and necessary training of the dental team in matters of behavior management and treatment strategies is needed to break the jinx that these special subjects are neglected by the society.

“Disabled doesnt mean worthless ….. its never about productivity, it is about humanity.”.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980. WHO. International classification of impairments, disabilities and handicaps: A manual of classification relating to the consequences of disease. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark CA, Vanek EP. Meeting the health care needs of people with limited access to care. J Dent Educ. 1984;48:213–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tesini DA. An annotated review of the literature of dental caries and periodontal disease in mentally retarded individuals. Spec Care Dentist. 1981;1:75–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1981.tb01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohmori I, Awaya S, Ishikawa F. Dental care for the severely handicapped children. Int Dent J. 1981;31:177–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiske J, Hyland K. Parkinson's disease and oral care. Dent Update. 2000;27:58–65. doi: 10.12968/denu.2000.27.2.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peter S. New Delhi: Arya (Medical) Publishing House; 2006. Essentials of preventive and community dentistry; pp. 124–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glassman P, Miller C. Dental disease prevention and people with special needs. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31:149–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacEntee MI. An existential model of oral health from evolving views on health, function and disability. Community Dent Health. 2006;23:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glassman P, Miller CE. Preventing dental disease for people with special needs: The need for practical preventive protocols for use in community settings. Spec Care Dentist. 2003;23:165–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2003.tb00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anaise JZ. Periodontal disease and oral hygiene in a group of blind and sighted Israeli teenagers (14-17 years) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1979;7:353–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1979.tb01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pieper K, Dirks B, Kessler P. Caries, oral hygiene and periodontal disease in handicapped adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986;14:28–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1986.tb01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw L, Shaw MJ, Foster TD. Correlation of manual dexterity and comprehension with oral hygiene and periodontal status in mentally handicapped adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:187–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsea AG, Karidis AG, Donta Bakoyianni C, Spyropoulos ND. Oral health status in Greek children and teenagers, with disabilities. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2001;26:111–8. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.26.1.705x15693372k1g7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bozkurt FY, Fentoglu O, Yetkin Z. The Comparison of various oral hygiene strategies in neuromuscularly disabled individuals. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2004;4:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al- Qahtani Z, Wyne AH. Caries experience and oral hygiene status of blind, deaf and mentally retarded female children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Odontostomatol Trop. 2004;27:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akpata ES, Al Shammery AR, Saeed HI. Dental caries, sugar consumption and restorative dental care in 12-13 year old children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:343–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S, Sharma J, Duraiswamy P, Kulkarni S. Determinants for oral hygiene and periodontal status among mentally disabled children and adolescents. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2009;27:151–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.57095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain M, Mathur A, Sawla L, Choudhary G, Kabra K, Duraiswamy P, et al. Oral health status of mentally disabled subjects in India. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:333–40. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oredugba FA. Oral health care knowledge and practices among group of a of deaf adolescents in Lagos, Nigeria. J Public Health Dent. 2004;64:118–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2004.tb02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owens PL, Kerker BD, Zigler E, Horwitz SM. Vision and oral health needs of individuals with intellectual disability. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2006;12:28–40. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan J. Why is Periodontal disease more prevalent and more severe in people with Downs syndrome. Spec Care Dentist. 2007;27:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2007.tb00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff AJ, Waldman HB, Milano M, Perlman SP. Dental students experiences with and attitudes toward people with mental retardation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:353–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pannuti CM, Saraiva MC, Ferraro A, Falsi D, Cai S, Lotufo RF. Efficacy of 0.5% chlorhexidene gel in control of gingivitis in Brazilian mentally handicapped patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:573–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldman HB, Swerdloff M, Perlman SP. You may be treating children with mental retardation and attention deficit hyperactive disorder in your dental practice. ASDC J Dent Child. 2000;67:241–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]