Abstract

Resorption of alveolar bone - a common sequel of tooth loss jeopardizes the functional and esthetic outcome of treatment, especially in the maxillary anterior areas. Therefore, augmentation of deficient alveolar ridges is an important aspect of dental implant therapy. A case of severe maxillary ridge deficiency successfully treated with horizontal ridge augmentation to facilitate implant placement is described. Ridge augmentation was achieved using a combination of autogenous block graft, particulate grafting, and guided bone regeneration (GBR). Follow-up was done next day, after ten days, three months, and six months. Various approaches can be followed in order to achieve an increase in the ridge width. In our case, we used a combination of different techniques for ridge augmentation. A significant improvement in ridge width was noticed at six months thus facilitating the placement of implants.

Keywords: Autogenous block graft, GBR, ridge augmentation

INTRODUCTION

Resorption of alveolar bone is a common sequel of tooth loss and presents a clinical problem, especially in the esthetic zone.[1] Implants placed without regard for prosthetic position often result in dental restorations that are functionally and esthetically compromised, and patients are left with less than optimal reconstruction.[2] The end goal of therapy is to provide a functional restoration that is in harmony with the adjacent natural dentition. To achieve this goal, augmentation of lost bone is often necessary.[1]

Bone is a dynamic structure with a continuous remodeling to ensure renewal of form and function.[1] Although bone tissue exhibits a large regeneration potential and may restore its original structure and function completely, bony defects may often fail to heal with bone tissue.[3] In order to facilitate and/or promote regeneration of lost bone, a variety of techniques may be employed, including particulate grafting, membrane use, block grafting, and distraction osteogenesis, either alone or in combination.[1] The biologic mechanisms forming the basis of bone augmentation include three basic processes: osteogenesis, osteoconduction, and osteoinduction.[3] Bone augmentation techniques may be used for the applications of extraction socket defect grafting, horizontal ridge augmentation, vertical ridge augmentation, and sinus augmentation.[1] We have described a case of horizontal ridge augmentation using a combination approach.

CASE REPORT

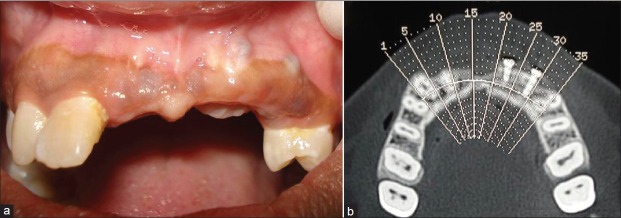

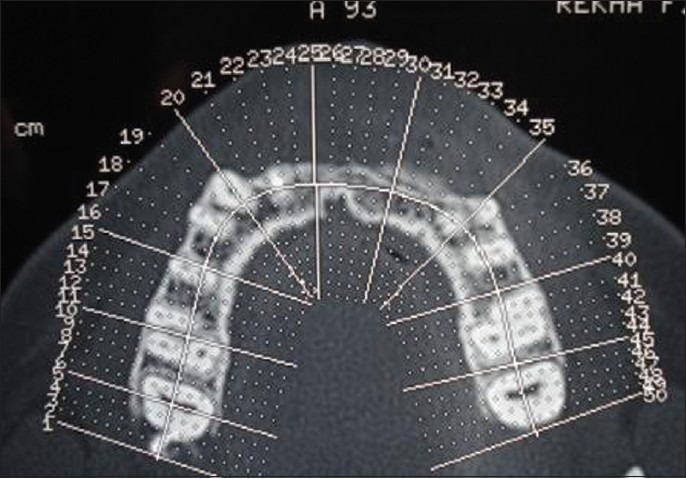

A 21-year-old female patient with missing maxillary central incisors, left lateral incisor, and left canine due to trauma wanted a permanent replacement of her missing teeth. Clinical examination [Figure 1], diagnostic impressions, face-bow transfers, bite registrations, photographs, radiographs, and a thorough history were obtained from the patient. A severe maxillary anterior ridge deficiency was noticed. To evaluate the bone width, ridge mapping was performed. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the edentulous area [Figure 2] was taken to accurately measure the available bone. The available bone dimensions were found to be as follows:

Figure 1.

Preoperative intra‑oral photograph

Figure 2.

CT scan of the edentulous area

Bone height at Tooth #11 = 16 mm

Bone height at Tooth #21 = 15 mm

Bone height at Tooth #22 = 15 mm

Bone height at Tooth #23 = 15 mm

Bone Width at Tooth # 11 = 3 mm

Bone Width at Tooth # 21 = 3 mm

Bone Width at Tooth # 22 = 3.5 mm

Bone Width at Tooth # 23 = 4 mm

Finding that the available bone width was inadequate for an implant supported bridge, we decided to horizontally augment the implant recipient site with a suitable substitute. Therefore, a ridge augmentation procedure using a combination of autogenous block graft (from mandibular symphysis), particulate graft and GBR was planned in order to achieve adequate ridge width to facilitate the placement of implants. The complete treatment plan was explained to the patient and duly signed consent was obtained. After completion of oral prophylaxis, surgical procedure was carried out at a later appointment.

Surgical procedure

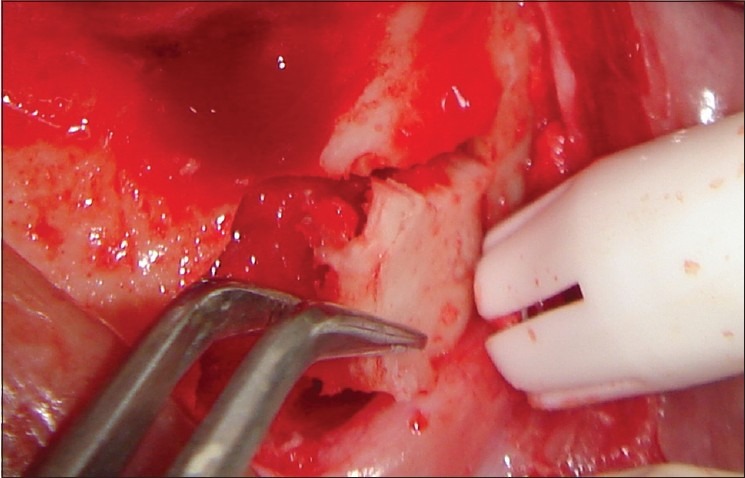

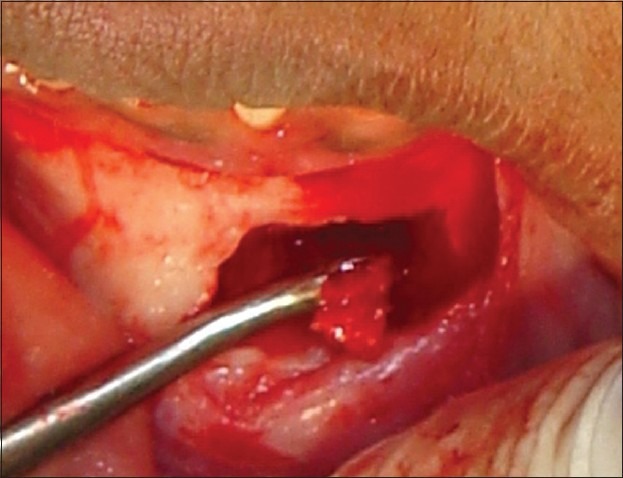

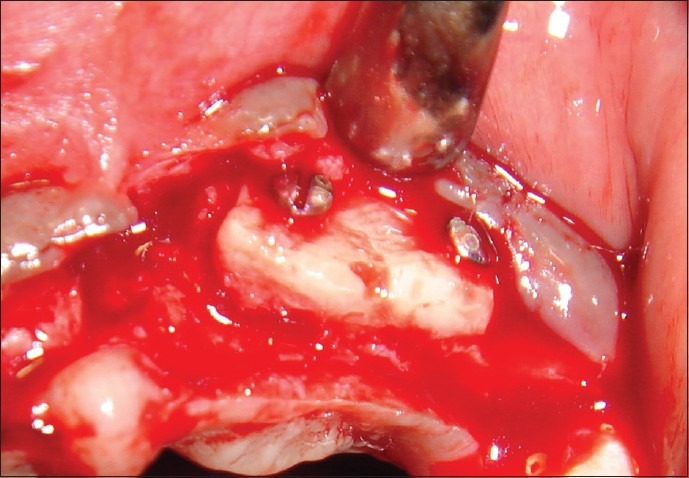

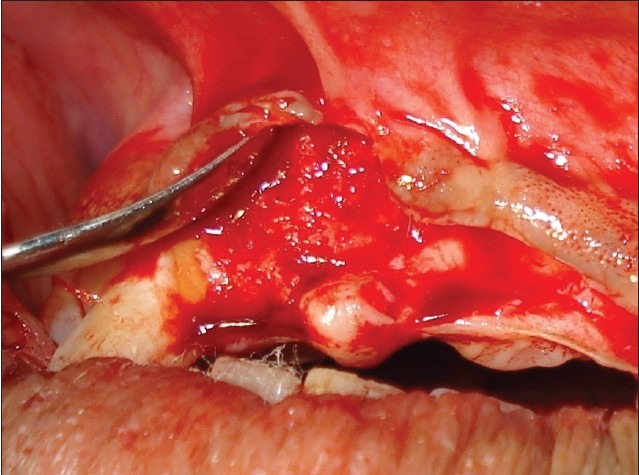

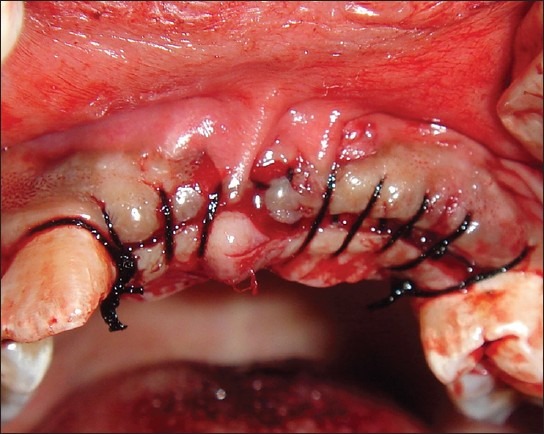

The donor and the recipient sites were anesthetized using 2% Lidocaine with 1: 100,000 epinephrine. Horizontal incision was given on the recipient site slightly lingual to the mid- crestal region. Full thickness flap was reflected. Bleeding points were created using a small round bur. Following the preparation of the recipient site, the donor site was reflected. An incision was placed about 10 mm below the mucogingival junction and extended between the distal aspects of the 2 mandibular canines. Full thickness flap was elevated with a periosteal elevator and reflected from the incision line to the inferior border of the mandible. A rectangular monocortical block graft was harvested from the mandibular symphyseal area [Figure 3]. Also, cancellous bone from the same area was obtained in the form of particulate graft with the help of a Molt curette [Figure 4]. The block graft was cut to appropriate size and anchored to fit the recipient site intimately. Once properly positioned, the graft was fixated with two titanium screws of 1.5 mm diameter each passing though the graft into the remaining native alveolar bone [Figure 5]. Particulate graft was placed in the right central incisor area since the length of the block graft was not sufficient to cover the entire edentulous span [Figure 6]. The entire area was covered with the help of a resorbable membrane* made of fish collagen [Figure 7]. Following this, the flap was replaced and the area was sutured [Figure 8]. Despite the use of periosteal releasing incision, we were not able to achieve a complete primary closure on the left side due to the size of the graft. However, the area was covered with a tin foil and a periodontal dressing was given over it in order to protect the recipient area.

Figure 3.

Monocortical block graft harvested from the mandibular symphyseal area

Figure 4.

Particulate graft harvested

Figure 5.

Block graft fixated to the recipient site

Figure 6.

Particulate graft placed

Figure 7.

GBR using fish collagen membrane

Figure 8.

Recipient site sutured

On reflection of the donor site, periapical granuloma was noticed with respect to the lower left central and lateral incisors, which had already been root canal treated. Hence, apicectomy was done for these teeth before closing the donor site [Figure 9]. Once the donor site was sutured [Figure 10], periodontal dressing was given for additional protection, and pressure bandage was given externally.

Figure 9.

Apicectomy done with respect to the lower left central and lateral incisors

Figure 10.

Donor site sutured

The patient was given post surgical instructions and oral hygiene instructions were reinforced. The patient was prescribed the antibiotic amoxicillin 500 mg three times daily for seven days to prevent nosocomial infection and anti-inflammatory agent ibuprofen 400 mg two times daily, for a period of five days. The use of 0.2% chlorhexidine mouth rinse two times a day was instituted for two weeks. Suture removal was done after 10 days. Post operative follow-up the next day, after 10 days, and three months showed uneventful healing at both the surgical sites. A removable partial denture was given to the patient provisionally. Significant improvement in the ridge width was noticed at six months [Figure 11]. All the initial examination procedures were repeated post operatively to aid in the final prosthetic plan. On re-examination, the available bone dimensions were as follows:

Figure 11.

Improved ridge width at 6 months. (a) Clinical picture; (b) CT scan

Bone height at Tooth #11 = 16 mm

Bone height at Tooth #21 = 15 mm

Bone height at Tooth #22 = 15 mm

Bone height at Tooth #23 = 15 mm

Bone Width at Tooth # 11 = 6 mm

Bone Width at Tooth # 21 = 4 mm

Bone Width at Tooth # 22 = 5.5 mm

Bone Width at Tooth # 23 = 7.5 mm.

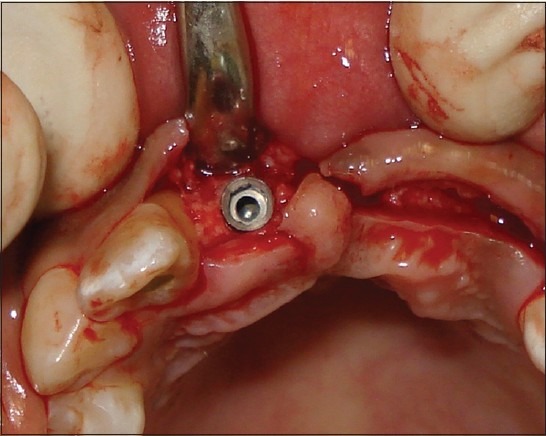

Dimensions of the available bone and clinical judgment aided in the selection of the right implant diameters for the patient. Two Implants† were placed, one at the right central incisor (diameter: 4.2 mm; length: 11.5 mm) and the other at the left canine area (diameter: 5 mm; length: 13 mm) [Figure 12]. Along with the abutments subsequently placed on the implants, teeth #12 and #24 were also used as abutments. Tooth preparation of the root canal treated #12 had to be done in such a way as to reduce the proclination of the tooth. A six unit implant supported bridge [Figure 13] was subsequently given to the patient.

Figure 12.

Placement of implant: Maxillary right central incisor

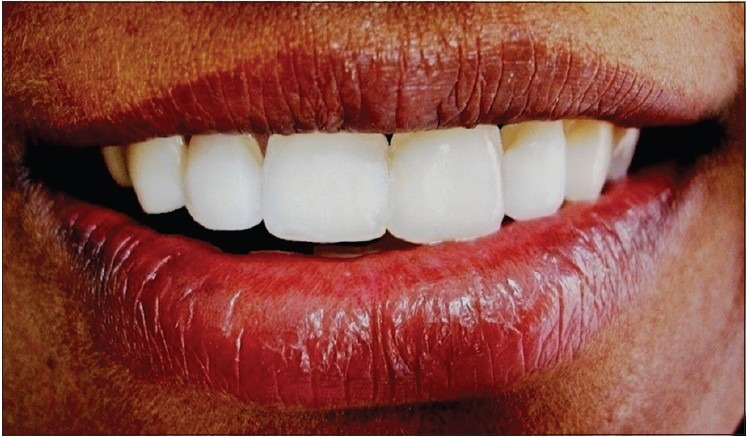

Figure 13.

Final prosthesis

DISCUSSION

Critical sized alveolar ridge defects may form following tooth loss, fractures, or pathological processes. Such defects compromise the ideal implant placement as prescribed prosthetically with an unfavorable outcome. Horizontal ridge augmentation has been described with the use of a variety of different techniques and materials.[1]

Guided tissue regeneration refers to the procedures attempting to regenerate specific anatomical structures through differential tissue responses.[4] GBR refers to the promotion of bone formation which is based on the principle of using barrier membranes for space maintenance over a defect promoting the ingrowth of osteogenic cells and preventing migration of undesired cells from the overlying soft tissues into the wound. A variety of nonresorbable and resorbable barrier membranes has been used in bone augmentation with the GBR concept.[1] We have used a resorbable collagen membrane in our case, in order to overcome some of the limitations of non resorbable membranes, such as the need for a second surgical procedure for their removal with the added risk of loss of some of the regenerated bone further to flap reflection. Also, an invitro study comparing resorbable and non resorbable membranes concluded that bioabsorbable membranes, particularly collagen and hyaluronic acid may promote bone regeneration through their activity on osteoblasts, thus suggesting that bioabsorbable membranes may be more suitable than non-resorbable membranes favoring bone regeneration and repair.[5]

Because of the lack of rigidity, most bioabsorbable membranes must be used in combination with a graft material for space maintenance in bone augmentation applications. Without underlying graft materials, barrier membranes may be compressed into the space of the bony defect by the overlying soft tissue during healing.[1] Therefore, a combination of particulate and monocortical block autografts was used along with the membrane. Autograft is considered the gold standard for most craniofacial bone grafting, including the treatment for various dental implant related defects. However, autografts have recognized limitations, such as donor site morbidity, potential resorption, size mismatch, and an inadequate volume of graft material.[1] In our case, we did not encounter any of these potential complications and uneventful healing was observed during the follow-up period. When using autogenous block grafting, a considerable amount of horizontal augmentation can be predictably added to the defect area. The stabilization and intimate contact of these block grafts to the recipient beds has been considered crucial for a successful outcome.[1] This was achieved with the help of bone fixation screws. Recipient bed preparation was done by creating several bleeding points to increase the rate of revascularization, the availability of osteoprogenitor cells, and the rate of remodeling. Autogenous bone grafts of both extra- and intraoral sources have been used in periodontal therapy due to their osteogenic potential.[6] The autogenous bone graft was obtained from the mandibular symphysis. Some advantages of this area for bone grafting procedures over other intra or extraoral sites are minimal resorption of the harvested bone graft, proximity to the recipient site and therefore reduced morbidity, no hospitalization, convenient surgical access, and no cutaneous scar formation.[7] Overall, larger bone volumes can be obtained from the symphysis compared to the ramus.[8]

This combination approach is useful in treating severe defects involving multiple missing teeth where individual approaches alone may not be sufficient to achieve the desired results. This is one of the few case reports using fish collagen membrane. Though the fish collagen membrane has been previously used for ridge augmentation in a case report,[9] to our knowledge, autogenous block and particulate graft in combination with a fish collagen membrane* has not been used previously.

In our case, we also carried out the procedure of apicectomy for the removal of periapical granuloma simultaneously when the flap was reflected at the donor site, thus avoiding the need for a second surgical procedure.

SUMMARY

Ridge augmentation of a long span edentulous area involving multiple missing teeth and severe ridge deficiency could be a challenging procedure, especially in the anterior area where both esthetics and function need to be restored. Since individual approaches may not provide the desired results, we used a combination of autogenous block graft, particulate graft and GBR with fish collagen membrane in order to achieve sufficient ridge width, thus facilitating the placement of implants.

Footnotes

Periocol GTR, Eucare Pharmaceuticals (P) Ltd., Chennai, India.

EZ Hi.Tec Implants system, Lifecare® devices (P) Ltd., Mumbai, India.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McAllister BS, Haghighat K. Bone augmentation techniques. J Periodontol. 2007;78:377–96. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klokkevold PR. Localized bone augmentation and implant site development. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, editors. Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006. pp. 1133–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang NP, Araujo M, Karring T. alveolar bone formation. In: Lindhe J J, Karring T, Lang NP, editors. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard; 2003. pp. 866–92. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinones CR, Caffesse RG. Current status of guided periodontal tissue regeneration. Periodontol 2000. 1995;9:55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1995.tb00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marinucci L, Lilli C, Baroni T, Becchetti E, Belcastro S, Balducci C, et al. In vitro comparison of bioabsorbable and non-resorbable membranes in bone regeneration. J Periodontol. 2001;72:753–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Position paper. Periodontal regeneration. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1601–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.9.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuler R, Verardi S, Ham BD. A new incision design for mandibular symphysis bone- grafting procedures. J Periodontol. 2005;76:846–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.5.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misch CM. Comparison of intraoral donor sites for onlay grafting prior to implant placement. Int J Oral Maxillo-fac Implants. 1997;12:767–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamed JB, Sudarsan S, Arun KV, Shivakumar B. Rehabilitation using single stage implants. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2009;13:32–40. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.51893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]