Abstract

Hemangiomas are common tumors characterized microscopically by proliferation of blood vessels. The congenital hemangioma is often present at birth and may become more apparent throughout life. They are probably developmental rather than neoplastic in origin. Despite their benign origin and behavior, hemangiomas in the oral cavity are always of clinical importance to the dental profession and require appropriate clinical management. This case report presents a case of capillary hemangioma of anterior palatal mucosa in a 13-year-old female.

Keywords: Capillary hemangioma, portwine stain, vascular malformations

INTRODUCTION

Vascular anomalies comprise of a widely heterogeneous group of tumors and malformations.[1] Hemangiomas are common tumors characterized microscopically by proliferation of blood vessels.[2] Hemangioma is sometimes congenital tumor, being present at birth, and then may exhibit no neoplastic tendency, only increasing in size at the same rate as the normal tissue.[3] There is a higher incidence in females (65%) than males (35%).[4] Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of the head and neck in children, but their occurrence on the palatal mucosa is extremely rare.[5] Hemangiomas may be cutaneous, involving skin, lips, and deeper structures; mucosal, involving the lining of the oral cavity; intramuscular involving masticatory and perioral muscles; or intra-osseous involving mandible and/or maxilla.[6]

The word “hemangioma” has been widely used in the medical and dental literature with reference to a variety of different vascular anomalies which has traditionally led to a significant amount of confusion regarding the nomenclature of these lesions.[7,8] In 1982, Mulliken and Glowacki described a classification scheme which is presently accepted. These vasoformative tumors are classified under 2 broad headings of hemangioma and vascular malformation. Hemangioma is further sub classified based on their histological appearance as: (1) capillary lesions; (2) cavernous lesions; and (3) mixed lesions.[7] A sclerosing variety also occurs that tends to undergo spontaneous fibrosis.[9]

Clinically hemangiomas are soft, sessile or pedunculated, and painless. They may be smooth or irregularly bulbous in outline. The color varies from deep red to purple and the tumor blanches on the application of pressure. This benign blood vessel tumor is occasionally seen on the palatal mucosa, where it occurs as a capillary or cavernous type, more commonly the former. Periodontally, these lesions often appear to arise from the interdental gingival papilla and to spread laterally to involve adjacent teeth.[10]

CASE REPORT

A female patient aged 13 years, reported to the Department of Periodontology, Govt. Dental College and Hospital, Patiala, with the chief complaint of a swelling in her anterior maxillary palatal mucosa since four to five months. She also complained of localized bleeding in that area on brushing. However, there was no pain, but slight discomfort while eating. Past history revealed that she had a swelling nine months back. It was initially small in size, gradually increased and stabilized after three to four weeks until the present size.

General examination

The patient was normally built for her age with no defect in gait or stature. There was no relevant medical history.

Intra-oral examination

On intra-oral examination, there was localized gingival growth between maxillary right central incisor and lateral incisor on the palatal aspect [Figure 1]. The lesion arised from interdental papillary region and was pedunculated with a distinct slender stalk. The lesion was bright-red, erythematous, and bilobulated with well-defined margins. The two distinct lobes measured about 5×4 cm and 3×2.5 cm in diameter. They were firm and rubbery in texture. No surface ulceration or secondary infection was noted. The labial gingiva in relation to both right central and lateral incisors was normal, while palatal surface in relation to right lateral incisor showed probing pocket depth of 4 mm accompanied with bleeding on probing. There was grade I mobility in right lateral incisor. The oral hygiene of the patient was reasonably good.

Figure 1.

Pre‑operative photograph showing localized gingival growth between maxillary right central incisor and lateral incisor on the palatal aspect

Investigations

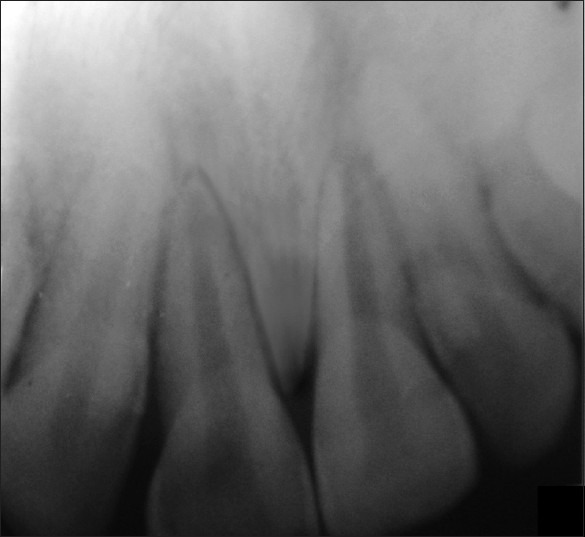

A complete hemogram, urine analysis, and intraoral periapical radiograph with respect to maxillary right central and lateral incisor (11, 12) were done. The laboratory investigations of blood and urine were within normal limits. Radiographically, there was no evidence of crestal bone loss and lamina dura was intact around the roots of both maxillary central and lateral incisors; however, slight rarefaction of bony trabeculae was noted [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

No evidence of crestal bone loss and lamina dura was intact around the roots of both maxillary central and lateral incisors

Management

Thorough scaling and root planing was carried out, and the patient was put on maintenance phase. After one week, surgical excision of the lesion was done under local anesthesia as a part of excisional biopsy. A thread was tied around stalk of pedunculated lesion and was stretched tightly so as to reduce the blood circulation to the lesion. The growth was then surgically excised along with the stalk and thorough curettage of the area was performed. The excised lesion was transported in 10% formalin to the laboratory for histopathological examination. Periodontal dressing was placed on the operated area, and the patient was given post-operative instructions; after one week, the dressing was removed. Lesion was completely healed after one month follow-up [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Post‑operative healed lesion at one month follow‑up

Histopathology report

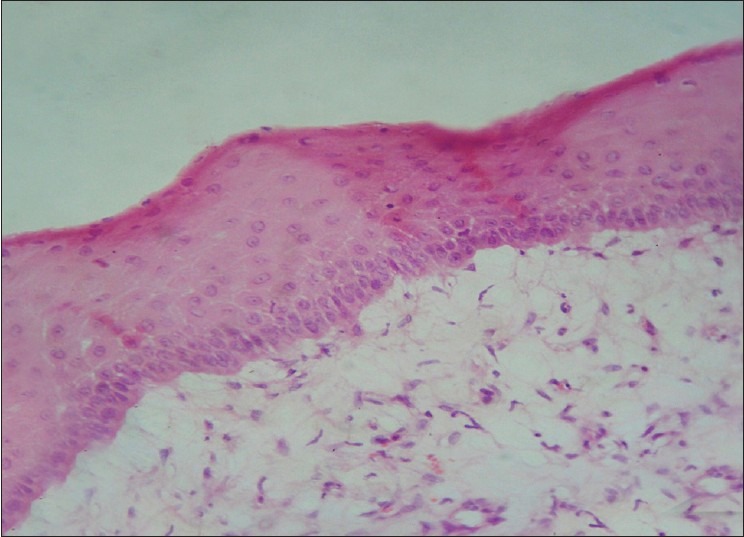

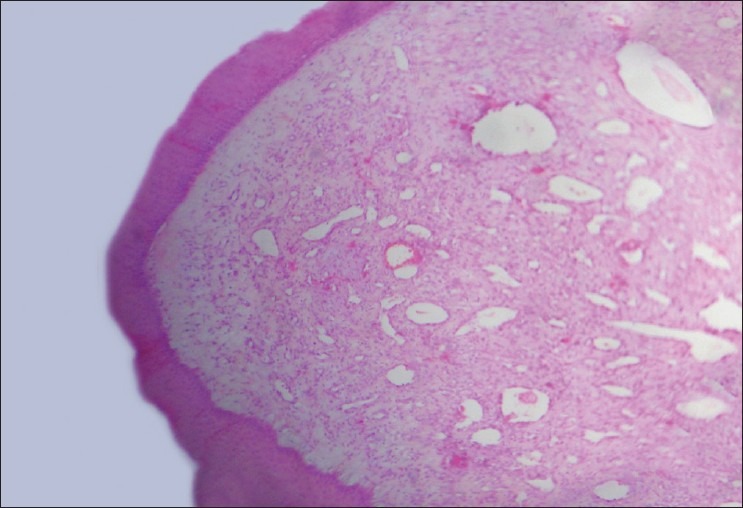

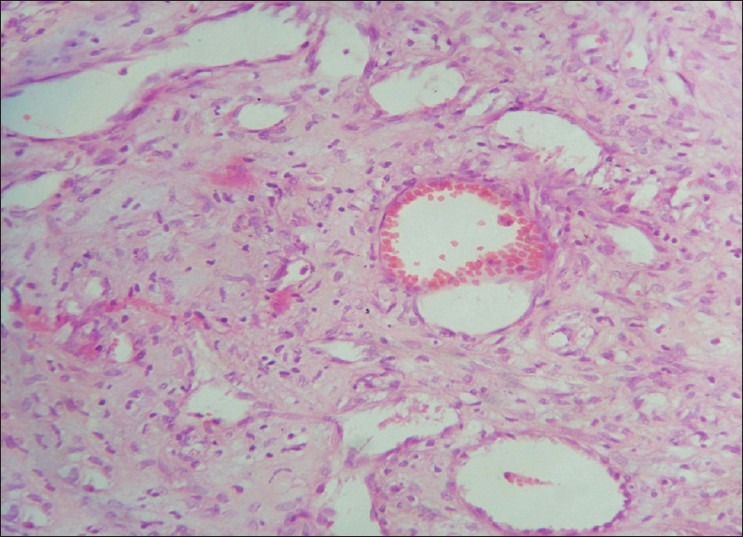

Histopathological examination revealed stratified squamous epithelium showed hypertrophy, hyperplasia with keratosis [Figure 4]. Beneath which many small and large thin-walled capillary channels were present. The capillaries were lined by a single layer of endothelial cells supported by a connective tissue stroma of varying density [Figure 5]. Sparse lymphocytes and plasma cells were seen scattered throughout stroma [Figure 6].

Figure 4.

Stratified squamous epithelium with hypertrophy, hyperplasia and keratosis. (H and E, 400×)

Figure 5.

Stratified squamous epithelium covering the connective tissue stroma involving small and large capillaries lined by a single layer of endothelial cells. (H and E, 40×)

Figure 6.

Capillaries with RBCs along with sparse lymphocytes and plasma cells scattered throughout stroma. (H and E, 400×)

Diagnosis

On the basis of history, clinical examination, and histopathological report, a diagnosis of capillary hemangioma was made.

DISCUSSION

Vascular lesions presenting as proliferations of vascular channels are tumor-like hamartomas when they arise in childhood; in adults (particularly elderly persons), benign vascular proliferations are generally varicosities. Approximately 85% of childhood-onset hemangiomas spontaneously regress after puberty, whereas a varix arises in older individuals, and once formed, does not regress.[11] Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of the head and neck in children, but their occurrence on the palatal mucosa is extremely rare.[5] In 80% of cases, hemangiomas occur as single lesions.[12] Moreover, capillary hemangiomas have a 3:1 female to male ratio and occur more frequently among Caucasians than other racial groups.[5]

They usually but not invariably follow a benign course. Although the exact cause is unknown, some authorities believe that this lesion is not true lesion, but rather a developmental anomaly or hamartoma.[2] it has also been hypothesized that angiogenesis likely plays a role in the vascular excess present. Cytokines, such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are known to stimulate angiogenesis. Excesses of these angiogenic factors or decreases of angiogenesis inhibitors (eg, gamma-interferon, tumor necrosis factor-beta, transforming growth factor-beta) have been implicated in the development of hemangiomas.[13]

Microscopically, capillary hemangioma is comprised of numerous intertwined capillary sized vessels lined by endothelial cells and usually filled with blood.[2]

Regarding treatment, most true hemangiomas require no intervention; they undergo spontaneous regression at an early age. Only 10-20% requires treatment because of their size, location or their behavior (Mullikan 1995).[14] Although different therapeutic procedures including microembolization, radiation, cryotherapy, sclerosing agents, corticosteroids and, recently, laser therapy have been reported, complete surgical excision of these lesions, if possible, offers the best chance of cure. In the present case, the treatment comprised of complete surgical excision of the lesion, care being taken to remove the entire base of the lesion followed by thorough curettage and root planing to remove the local factors from the area.[2]

The prognosis of hemangioma, in general, is excellent since it does not tend to recur or undergo malignant transformation following adequate treatment.[15]

In the case presented here, the patient was recalled at regular intervals and no sign of recurrence was reported till one year follow-up.

CONCLUSION

Early detection and biopsy is necessary to determine the clinical behavior of the tumor and potential dentoalveolar complications. Although a rare benign tumor of the oral cavity, capillary hemangioma is important to the periodontists because of its associated gingival vascular features and complications in the form of impaired nutrition and oral hygiene, increased accumulation of plaque and microorganisms, and increased susceptibility to oral infections, which can impair the systemic health of the affected individual. In addition, the periodontal surgical management of hemangiomas should be performed with caution because the tissues may bleed profusely intraoperatively and postoperatively.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang MW. Updated classification of hemangiomas and other vascular anomalies. Lymphat Res Biol. 2003;1:259–65. doi: 10.1089/153968503322758067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1983. A Textbook of Oral Pathology; pp. 154–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colyer JF, Sprawson E. 4th ed. London: Butterworth and Co; 1953. Dental surgery and Pathology; pp. 1042–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dilley DC, Siegel MA, Budnick S. Diagnosing and treating common oral pathologies. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1991;38:1227–64. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lale AM, Jani P, Coleman N, Ellis PD. A palatal hemangioma in a child. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:677–8. doi: 10.1017/s002221510014143x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun IF, Levy S, Hoffman J. The use of transarterial microembolization in the management of hemangiomas of the perioral region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:239–48. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller BU, Mulliken JB. The infant with a vascular tumour. Semin Perinatol. 1999;23:332–40. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(99)80041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hand JL, Frieden IJ. Vascular birth marks of infancy: Resolving nosologic confusion. Am J Med Genet. 2002;108:257–64. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin DC. Treatment of maxillary hemangioma with a sclerosing agent. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:247–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carranza FA. 1st ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co London; 1990. Glickman's Clinical Periodontology; pp. 335–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg MS, Glick M. Blue/purple vascular lesions. In: Burket S, editor. Oral medicine diagnosis and treatment. Canada: BC Decker; 2003. pp. 127–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders co; 2002. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology; pp. 467–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang J, Most D, Bresnick S, Mehrara B, Steinbrech DS, Reinisch J, et al. Proliferative hemangiomas: Analysis of cytokine gene expression and angiogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emedicine [Internet source]. Sloan SB. Oral Hemangioma Treatment & Management. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 18]. Superscript no. 26. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1080571-treatment .

- 15.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 2009. A Textbook of Oral Pathology; p. 143. [Google Scholar]