Abstract

During pregnancy, proper hepatobiliary transport and bile acid synthesis protect the liver from cholestatic injury and regulate the maternal and fetal exposure to bile acids, drugs, and environmental chemicals. The objective of this study was to determine the temporal messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein profiles of uptake and efflux transporters as well as bile acid synthetic and conjugating enzymes in livers from virgin and pregnant mice on gestational days (GD) 7, 11, 14, and 17 and postnatal days (PND) 1, 15, and 30. Compared with virgins, the mRNAs of most transporters were reduced approximately 50% in pregnant dams between GD11 and 17. Western blot and immunofluorescence staining confirmed the downregulation of Mrp3, 6, Bsep, and Ntcp proteins. One day after parturition, the mRNAs of many uptake and efflux hepatobiliary transporters remained low in pregnant mice. By PND30, the mRNAs of all transporters returned to virgin levels. mRNAs of the bile acid synthetic enzymes in the classic pathway, Cyp7a1 and 8b1, increased in pregnant mice, whereas mRNA and protein expression of enzymes in the alternative pathway of bile acid synthesis (Cyp27a1 and 39a1) and conjugating enzymes (Bal and Baat) decreased. Profiles of transporter and bile acid metabolism genes likely result from coordinated downregulation of transcription factor mRNA (CAR, LXR, PXR, PPARα, FXR) in pregnant mice on GD14 and 17. In conclusion, pregnancy caused a global downregulation of most hepatic transporters, which began as early as GD7 for some genes and was maximal by GD14 and 17, and was inversely related to increasing concentrations of circulating 17β-estradiol and progesterone as pregnancy progressed.

Key Words: pregnancy, transporter, liver, mice, bile acids, nuclear receptors

It is estimated that prescription drugs (excluding vitamins and minerals) are used in 35–64% of pregnant women in the United States (Daw et al., 2011). Pregnancy causes physiological changes in body weight, cardiac output, blood flow, and glomerular filtration that can influence drug disposition and action in pregnancy. The pharmacokinetics of some prescription drugs has been characterized in pregnant women (Beigi et al., 2011; Eyal et al., 2010; Freeman et al., 2008; Klier et al., 2007; Salman et al., 2010) and rodents (Zhang et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2008). There are also changes in the expression of metabolic genes in response to pregnancy that influence the disposition of chemicals (reviewed in Anderson, 2005). Further investigation is needed to better understand these adaptive molecular changes during pregnancy.

Research has largely focused on how pregnancy regulates the hepatic expression and function of drug metabolism enzymes. Pharmacokinetic assessments and in vitro mechanistic studies suggest upregulation of cytochrome P450 (Cyp) 2D6 and 3A and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A4 as well as repression of CYP1A2 during human pregnancies (Chen et al., 2009; Claessens et al., 2010; Hebert et al., 2008; Knutti et al., 1981). Expression profiling of livers from pregnant mice demonstrates some changes in metabolic genes similar to changes in humans (Koh et al., 2011; Luquita et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2008). Less is known about regulation of transporters responsible for chemical excretion during pregnancy in rodents. During late pregnancy, rats have reduced expression of uptake transporters including the sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (Ntcp, Slc10a1) and organic anion transporting polypeptide (Oatp, Slco) 1a4, as well as downregulation of several efflux transporters, such as the multidrug resistance–associated proteins (Mrp, Abcc) 2, 3, and 6 (Arrese et al., 2003; Cao et al., 2002). To date, most studies investigating transporters in pregnancy have focused on late gestation and the postpartum period (Cao et al., 2001, 2002). With the exception of the breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp, Abcg2) and the multidrug resistance protein (Mdr1, Abcb1) (Wang et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008), little is known about the regulation of maternal hepatic transporters in mice during early pregnancy, a period when altered chemical exposure may have critical influence on fetal development.

During pregnancy, rodents and humans exhibit elevated serum and hepatic bile acid levels (Heikkinen et al., 1981; Laatikainen and Ikonen, 1977; Milona et al., 2010). Transporters including NTCP, OATPs, bile salt export pump (BSEP, ABCB11), MRP3 and 4, and MDR are important in excreting endogenous substances such as bile acids. Genetic variants in BSEP and MRP2 as well as the farnesoid X receptor (FXR, NR1H4) contribute to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in humans (Dixon et al., 2009; Pauli-Magnus et al., 2010; Sookoian et al., 2008; Van Mil et al., 2007). These data support investigating transporter and bile acid regulation during pregnancy in order to better understand the consequences of loss-of-function genetic variants. Recent work suggests that pregnancy in mice resembles a state of FXR inactivation with downregulation of uptake and efflux transporters and a reduced capacity for downregulation of key bile acid synthetic enzymes, Cyp7a1 and 8b1, by the transcriptional repressor small heterodimeric partner (Shp, Nr0b2) (Milona et al., 2010). Likewise, coimmunoprecipitation experiments suggest that estradiol and/or its metabolites may interfere with FXR activity during pregnancy (Milona et al., 2010).

Mice are becoming more frequently used for perinatal exposure in toxicology studies. Therefore, it is necessary to dissect how pregnancy regulates transporters in this species. Likewise, a more comprehensive investigation of bile acid pathways including conjugating enzymes such as bile acid CoA ligase (Bal, Slc27a5) and bile acid CoA:amino acid N-acetyltransferase (Baat) during different periods of pregnancy is needed. The purpose of the current study was (1) to determine the temporal mRNA and protein expression patterns of maternal hepatobiliary transporters and bile acid synthetic and conjugating enzymes in relation to changes in liver weight and hormones, and (2) to assess whether expression and activity of transcription factor pathways mirror regulation of target genes in dams during pregnancy and lactation. Seven time points were selected that included a range of gestational days (GD7, 11, 14, and 17 with parturition on days 19–20) and postnatal days (PND1, 15, and 30). Candidate regulatory transcription factors include FXR, liver X receptor (LXR, NR1H2), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR, NR1I3), pregnane X receptor (PXR, NR1I2), and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha (PPARα, NR1C1). These transcription factors are important in regulating xenobiotic disposition, cholesterol and oxysterol homeostasis, and fatty acid metabolism and are altered by pregnancy in rodents (Sweeney et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Adult male and female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA) and allowed to acclimatize for at least 1 week. A subset of female mice was mated overnight with male mice and separated in the morning (designated GD0). Mice were allowed access to feed and water ad libitum. All mice were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited animal care facility in temperature-, light-, and humidity-controlled rooms. Mice were housed on corn-cob bedding and were given ad libitum access to water and standard rodent chow. Animal studies were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center and Rutgers University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Serum and livers were collected from pregnant and time-matched virgin mice (n = 3–4) on GD7, 11, 14, and 17 and PND1, 15, and 30. It should be noted that there were only two virgin mice on PND30. Parturition occurred between GD19 and 21. Pups were housed with dams until weaning on PND21. Dams had an average of 7.8±0.5 fetuses per litter. Livers were weighed, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until used for analysis.

Chemicals.

Unless otherwise specified, chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

Serum analytes.

Serum progesterone and 17β-estradiol were quantified using ELISA kits from Genway (San Diego, CA). Total serum bile acid levels were quantified by a colorimetric assay from Bioquant (San Diego, CA). All assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

RNA isolation.

Total RNA was isolated from frozen livers using RNA-Bee reagent (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, TX) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of total RNA in each sample was quantified spectrophotometrically at 260nm, and purity was confirmed by 260/280nm ratio. RNA integrity was assessed by visualization of 18S and 28S rRNA bands on formaldehyde-agarose gels.

mRNA quantification.

A combination of mRNA techniques was used for gene expression profiling depending upon the availability of primers and samples. Liver transporter and bile acid mRNA expression was determined by the Quantigene Plex 2.0 Reagent System (Panomics, Inc., Fremont, CA). Individual bead-based oligonucleotide probe sets specific for each gene examined were developed by Panomics, Inc. The Panomics plex set 321021 was used (information available at http://www.panomics.com). Ribosomal protein L13A (Rpl13a) mRNA expression was used as an internal control for each sample. Samples were analyzed by using a Bio-Plex System Array reader with Luminex 100 xMAP technology, and data were acquired using Bio-Plex Data Manager Software Version 5.0 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Panomics, Inc.). Briefly, 0.5 μg of total RNA was incubated overnight at 53°C with X-MAP beads containing oligonucleotide capture probes, label extenders, and blockers. The next day, beads and bound target RNA were washed and subsequently incubated with preamplifier at 46°C for 1h. Next, samples were washed and incubated with amplifier at 46°C for 1h. Subsequently, samples were washed and incubated with label probe (biotin) at 46°C for 1h. Samples were washed again and incubated with streptavidin-conjugated R-phycoerythrin, which binds biotinylated probes, at room temperature for 30min. Streptavidin-conjugated R-phycoerythrin fluorescence was then detected for each analyte within each sample. All data were standardized to Rpl13A and normalized to time-matched virgin mice.

Expression of transcription factors and their target genes with the exception of FXR and Shp was quantified by RT-qPCR. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated with the First Strand SuperScript cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA purity and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). For qPCR, specific forward and reverse primers for each gene were added to 1 µg of cDNA from each sample (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for detection of amplified products. qPCR was performed in a 384-well plate format using the ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Ct values were converted to △△Ct values by adjusting to Rpl13a.

The mRNA expression of mouse Bal, Baat, FXR, and Shp was quantified using the branched DNA signal amplification assay (QuantiGene, High Volume Branched DNA Signal Amplification Kit; Panomics, Inc.) (Hartley and Klaassen, 2000) using published sequences (Csanaky et al., 2009; Cui et al., 2012).

Western blot analysis.

Livers were homogenized in buffer containing 0.25M sucrose and 10mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Proteins (50 µg/lane) were electrophoretically resolved using polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen). Gels were transblotted overnight at 4ºC onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Western blot staining of Mrp2-4, 6, Bsep, and Ntcp was performed as described previously (Aleksunes et al., 2008). The following antibodies were used for Western blot staining of bile acid synthetic and conjugating enzymes: Cyp27a1 (Abcam, ab126785, 1:1000 primary dilution, Cambridge, MA), Cyp39a1 (Abcam, ab79981, 1:50 primary dilution), Baat (Abcam, ab83882, 1:1000 primary dilution), and Bal (Abcam, ab97884, 1:500 primary dilution). Equal protein loading was confirmed by β-actin. The β-actin antibody was purchased from Abcam (ab8227). Detection and semiquantification of protein bands were performed using a FluorChem imager (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Indirect immunofluorescence.

Livers were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound and brought to −20°C. Cryosections (6 μm) were thaw-mounted onto Superfrost glass slides (Fisher Scientific) and stored at −80°C with desiccant until use. Tissue sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5min. Immunofluorescence analysis was limited to Mrp2-4, 6, Bsep, and Ntcp. Liver sections were blocked with 5% goat serum/PBS with 0.1% Triton X (PBS-Tx) for 1h and then incubated with Mrp2, Mrp3 M3II-2, Mrp6 M6II-68, Ntcp K4, or Bsep K44 primary antibody diluted 1:100 in 5% goat serum/PBS-Tx for 2h at room temperature. Antibodies were provided by Dr Bruno Stieger (Mrp2, Ntcp, Bsep) and Dr George Scheffer (Mrp3, Mrp6). After incubation with primary antibody, the sections were washed and incubated for 1h with goat anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor 488 IgG (Invitrogen) diluted 1:200 in 5% goat serum/PBS-Tx. Sections were air dried and mounted in Prolong Gold with 4‘,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen). GD17 tissues were used for immunofluorescent staining because protein expression of efflux transporters as determined by Western blot was altered at this time point. Images were acquired on a Zeiss Observer D1 microscope (Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY) with an X-cite series 120Q fluorescent illuminator and a Jenoptik camera with ProgRes CapturePro 2.8 software (Jenoptik, Easthampton, MA). All sections were stained and imaged under uniform conditions for each antibody. Negative controls without antibody were also included (data not shown).

Statistical analysis.

The software program GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Differences between virgin mice and pregnant dams at each time point were determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Differences were considered statistically significance at p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

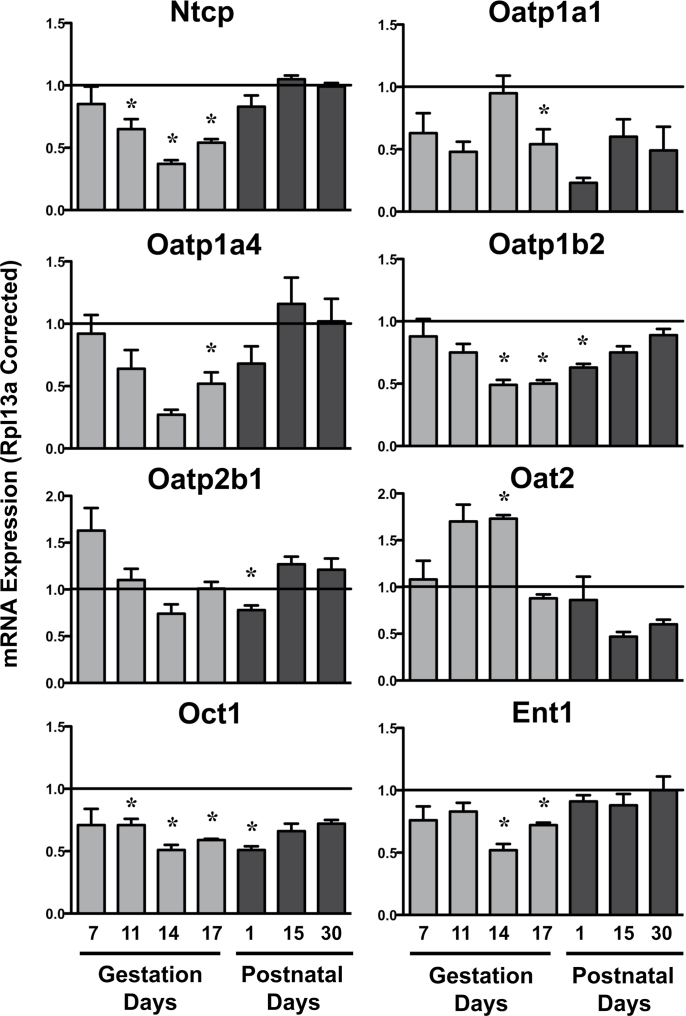

Hepatic Uptake Transporter mRNA in Pregnant and Lactating Mice

Expression of basolateral uptake transporters was largely unchanged on GD7 (Fig. 1). Levels of Ntcp, Oatp1a1, 1a4 (p = 0.07), 1b2, organic cation transporter 1 (Oct1, Slc22a1), and equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (Ent1, Slc29a1) mRNA decreased by at least 50% compared with virgin control mice between GD11 and 17. Conversely, organic anion transporter 2 (Oat2, Slc22a7) mRNA increased 70% on GD11 (p = 0.06) and 14. On PND1, mRNA expression of Oatp1a1, 1b2, 2b1, and Oct1 remained reduced, whereas Ntcp, Oatp1a4, Oat2, and Ent1 returned to baseline. No significant mRNA changes were observed on PND15 and 30.

FIG. 1.

Hepatic mRNA expression of uptake transporters in pregnant and lactating mice. mRNA expression of uptake transporters was quantified using total hepatic RNA from virgin and pregnant mice on GD7, 11, 14, and 17 and PND1, 15, and 30. Data were normalized to virgin controls at each time point (set to 1.0) and presented as mean relative expression ± SE. Light gray bars represent pregnant mice, and dark gray bars represent lactating mice. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) compared with time-matched virgin mice. It should be noted that the statistical analysis revealed a value of p = 0.06 for Oat2 mRNA on GD11 and PND15 and a value of p = 0.07 for Oatp1a4 mRNA on GD14.

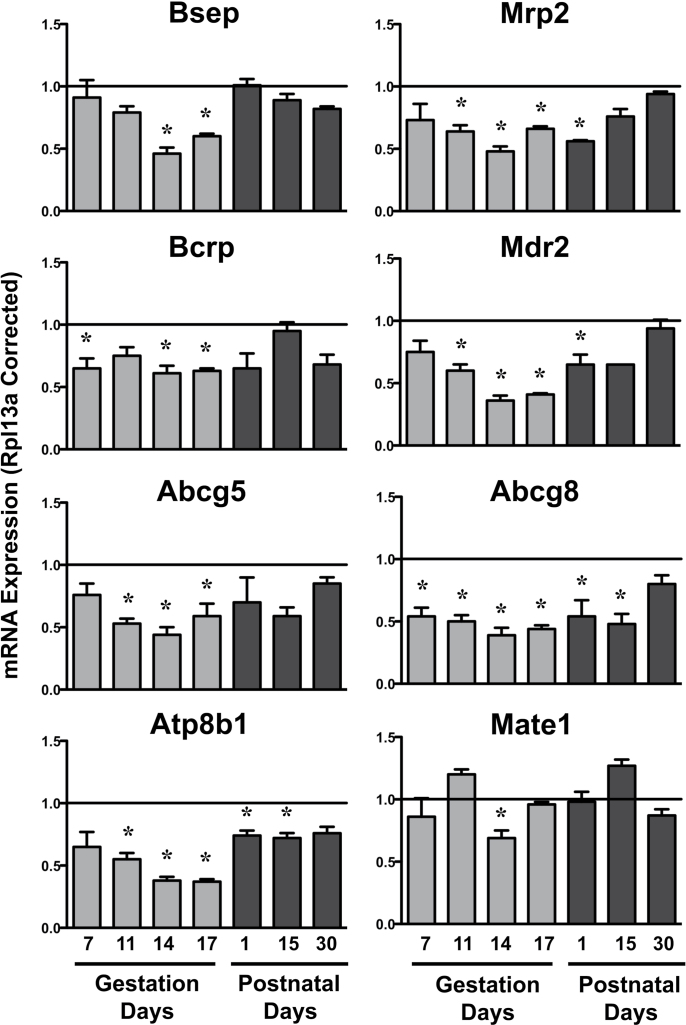

Hepatic Efflux Transporter mRNA and Protein in Pregnant and Lactating Mice

Compared with virgin controls, mRNA expression of some canalicular efflux transporters (Bcrp and Abcg8) began to decline as early as GD7 (Fig. 2). By GD11 and 14, all canalicular and most basolateral efflux transporter mRNAs were reduced (Figs. 2 and 3). Mdr2, Abcg5, Abcg8, Atp8b1, Mrp3, and Mrp6 mRNA in pregnant dams were downregulated by at least 50%, with marked repression of Mrp3 to approximately 14% of virgin controls on GD14 and 17. Interestingly, Mrp4 mRNA increased 63% on GD11 in pregnant dams. By PND1, mRNA levels of some efflux transporters remained low (Mrp2, Mdr2, Abcg8, Atp8b1, Mrp6), whereas the other transporters returned to virgin control levels. Notably, Atp8b1 and Abcg8 mRNA continued to be decreased on PND15. By PND30, the mRNA expression of all efflux transporters was similar to virgin control mice.

FIG. 2.

Hepatic mRNA expression of canalicular efflux transporters in pregnant and lactating mice. mRNA expression of canalicular efflux transporters was quantified using total hepatic RNA from virgin and pregnant mice on GD7, 11, 14, and 17 and PND1, 15, and 30. Data were normalized to virgin controls at each time point (set to 1.0) and presented as mean relative expression ± SE. Light gray bars represent pregnant mice, and dark gray bars represent lactating mice. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) compared with time-matched virgin mice.

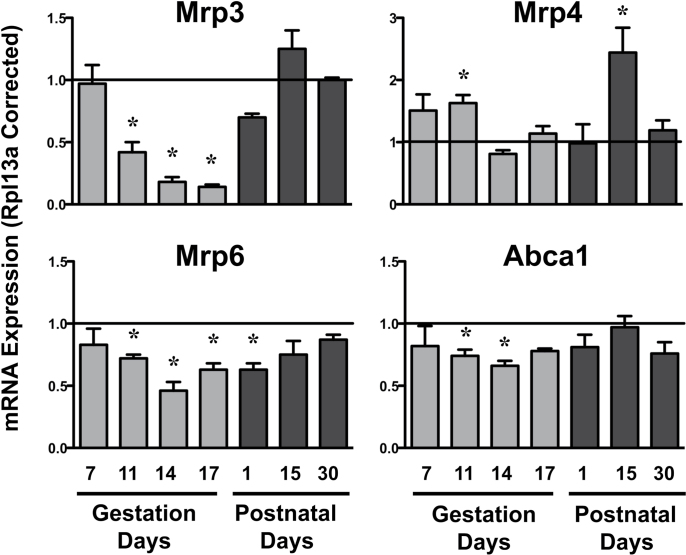

FIG. 3.

Hepatic mRNA expression of basolateral efflux transporters in pregnant and lactating mice mRNA expression of basolateral efflux transporters was quantified using total hepatic RNA from virgin and pregnant mice on GD7, 11, 14, and 17 and PND1, 15, and 30. Data were normalized to virgin controls at each time point (set to 1.0) and presented as mean relative expression ± SE. Light gray bars represent pregnant mice, and dark gray bars represent lactating mice. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) compared with time-matched virgin mice.

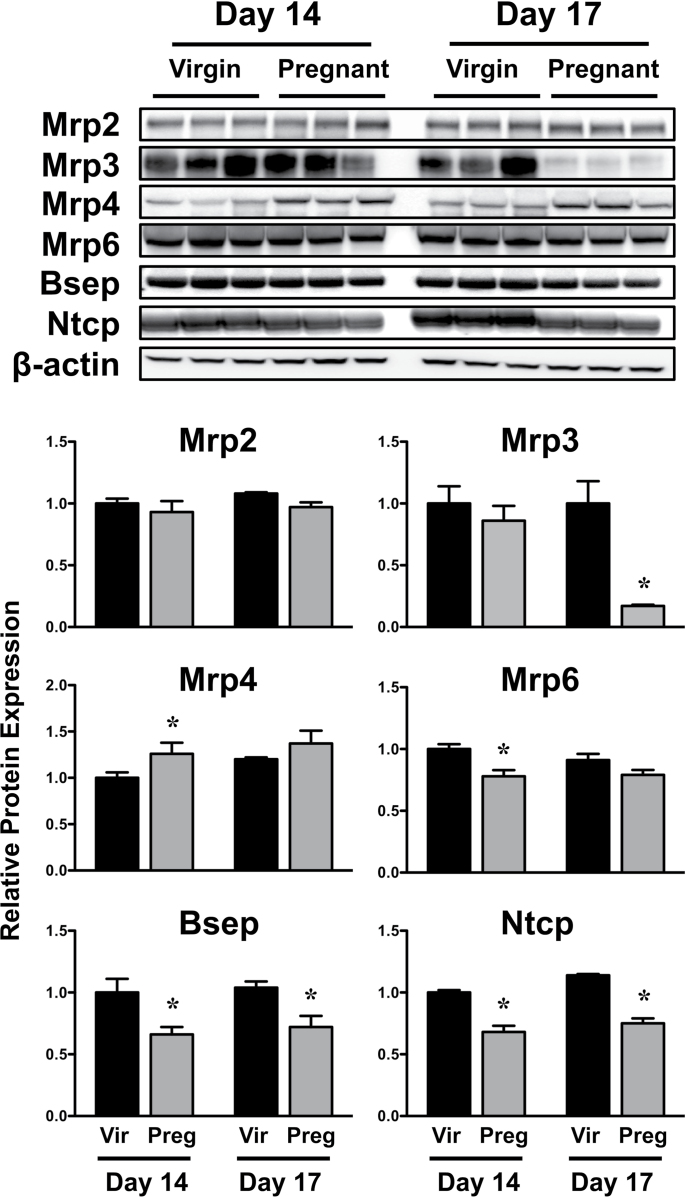

Western blot and immunofluorescent staining were performed on livers from virgin and pregnant mice on GD14 and 17 because the majority of mRNA changes occurred at these time points. Protein analysis was limited to a select number of transporters with antibodies capable of detection in mouse tissues. Expression of Bsep and Ntcp proteins was reduced 25–35% on GD14 and 17 (Fig. 4). In pregnant mice, Mrp3 protein was reduced to 17% of virgin control levels on GD17. Mrp6 protein was also reduced on GD14. There was a slight increase in Mrp4 protein on GD14.

FIG. 4.

Hepatic expression of transporter proteins in virgin and pregnant mice. Western immunoblots were performed using liver homogenates from virgin and pregnant mice on GD14 and 17 and protein band intensity was quantified. Data were normalized to virgin mice time matched to GD14 and presented as mean relative expression ± SE. Black bars represent virgin mice, and light gray bars represent pregnant mice. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) compared with time-matched virgin mice.

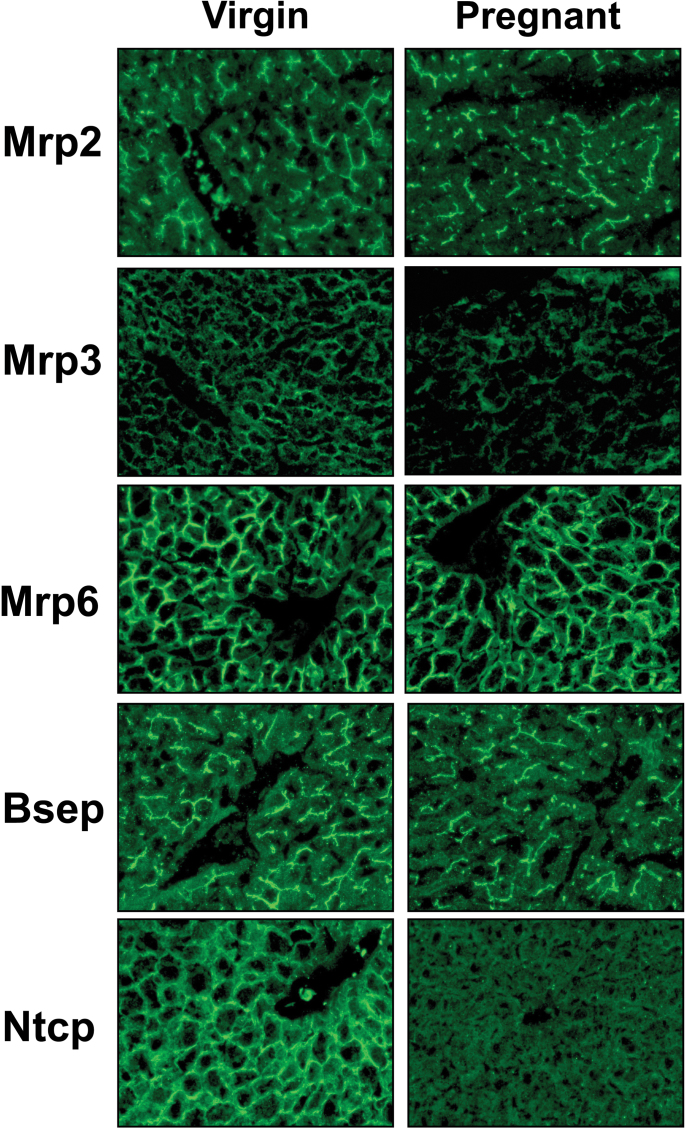

Indirect immunofluorescent staining of liver sections revealed basolateral expression of Mrp3, Mrp6, and Ntcp proteins and canalicular localization of Mrp2 and Bsep proteins (Fig. 5). The intensity of Mrp3 and Ntcp protein staining was markedly reduced in livers of pregnant dams on GD17. In addition, there were modest decreases in staining of Mrp2, Mrp6, and Bsep proteins. Mrp4 staining was low, and little difference was observed between virgin and pregnant mice (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Hepatic localization and staining of transporter proteins in virgin and pregnant mice. Indirect immunofluorescence (green) against canalicular transporters Mrp2 and Bsep and sinusoidal transporters Mrp3, Mrp6, and Ntcp was conducted on liver cryosections (6 μm) obtained from virgin and pregnant mice on GD17. Representative centrilobular regions are shown. Magnification ×40.

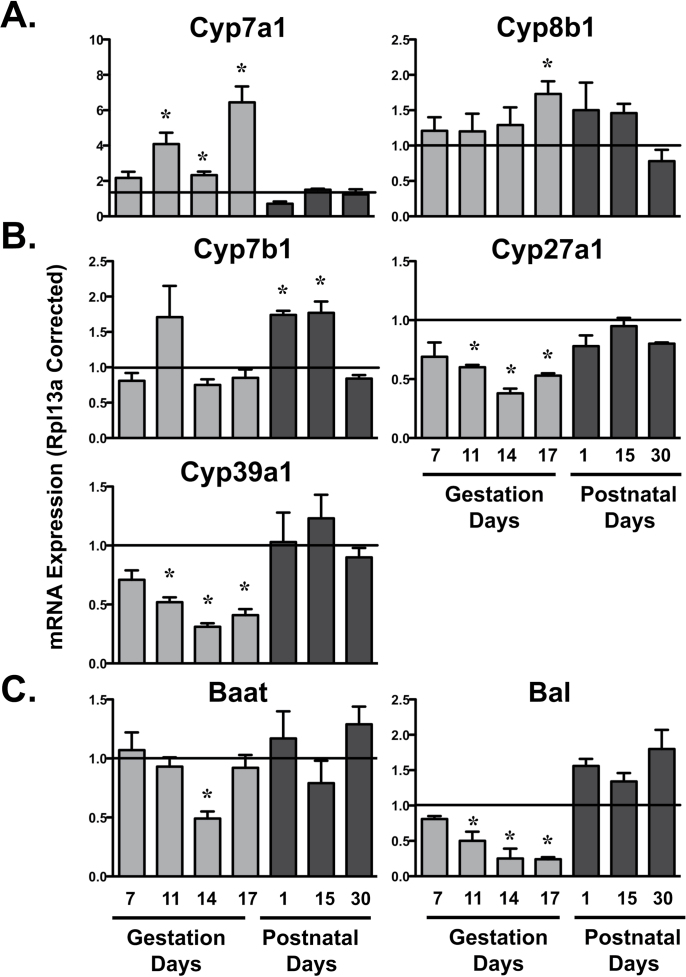

Hepatic Bile Acid Synthetic and Conjugating Enzyme mRNA and Protein in Pregnant and Lactating Mice

Expression of rate-limiting classic pathway bile acid synthetic genes, Cyp7a1 and 8b1, was upregulated in pregnant dams (Fig. 6A). Cyp7a1 mRNA increased between 2.2- and 6.5-fold during GD11 to 17, whereas Cyp8b1 mRNA increased only 73% on GD17. mRNA levels of alternate pathway bile acid genes, Cyp7b1, 27a1, and 39a1, were differentially expressed in time-dependent manners (Fig. 6B). Cyp27a1 and 39a1 mRNA decreased in pregnant dams up to 60–70% of virgin control mice between GD11 and 17 and returned to normal levels following parturition. Conversely, Cyp7b1 mRNA increased 75% in dams on PND1 and 15. Expression of bile acid conjugating genes was also quantified (Fig. 6C). Levels of Bal mRNA declined to 25% of virgin controls between GD11 and 17. Baat mRNA was reduced 50% on GD14.

FIG. 6.

Hepatic mRNA expression of bile acid synthetic and conjugating enzymes in pregnant and lactating mice mRNA expression of bile acid synthetic classic (A), alternative (B), and conjugation (C) enzymes was quantified using total hepatic RNA from virgin and pregnant mice on GD7, 11, 14, and 17 and PND1, 15, and 30. Data were normalized to virgin controls at each time point (set to 1.0) and presented as mean relative expression ± SE. Light gray bars represent pregnant mice, and dark gray bars represent lactating mice. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) compared with time-matched virgin mice.

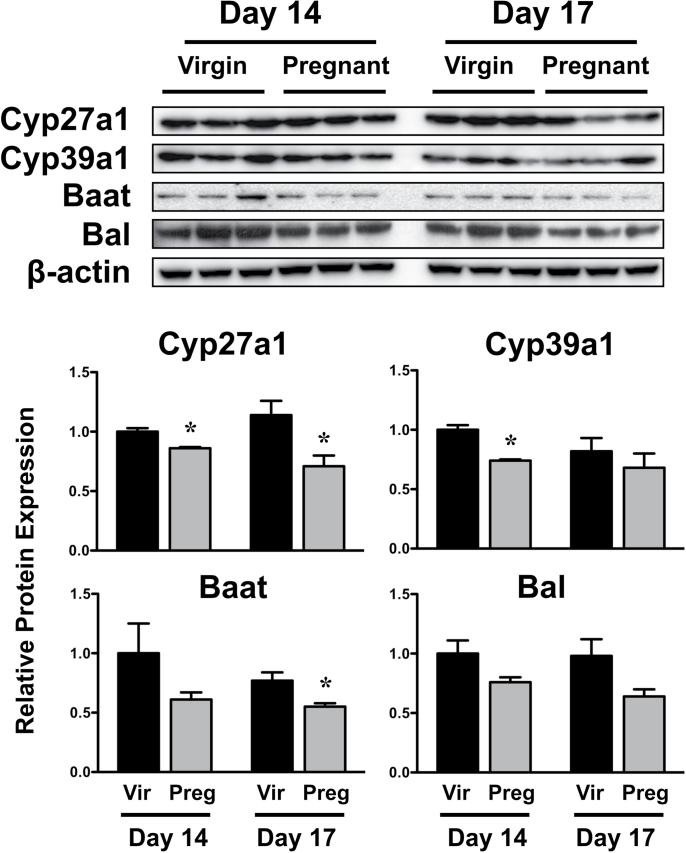

Western immunoblot analysis was conducted for enzymes involved in the alternate pathway of bile acid synthesis (Cyp27a1, 39a1) and conjugation of bile acids (Baat and Bal) (Fig. 7). Cyp27a1 and 39a1 protein decreased 15–25% in pregnant mice on GD14. Similarly, Baat protein levels were reduced on GD17. The protein expression of Bal also tended to decrease on GD14 and 17; however, these changes were not statistically significant.

FIG. 7.

Hepatic expression of bile acid synthesis and conjugating proteins in virgin and pregnant mice. Western immunoblots were performed using liver homogenates from virgin and pregnant mice on GD14 and 17 and protein band intensity was quantified. Data were normalized to virgin mice time matched to GD14 and presented as mean relative expression ± SE. Black bars represent virgin mice, and light gray bars represent pregnant mice. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) compared with time-matched virgin mice.

Liver and Body Weights in Pregnant and Lactating Mice

Because of the marked downregulation of transporters and alternate bile acid synthesis and conjugating enzymes between GD11 and 17, additional experiments were conducted to determine whether these mRNA and protein changes correlated with physiological changes of pregnancy. As expected, absolute liver and body weights were elevated in pregnant dams at all time points evaluated (Supplementary fig. 1). When expressed as a ratio of liver to body weight, notable increases were observed on GD7 and 11, and PND1, 15, and 30.

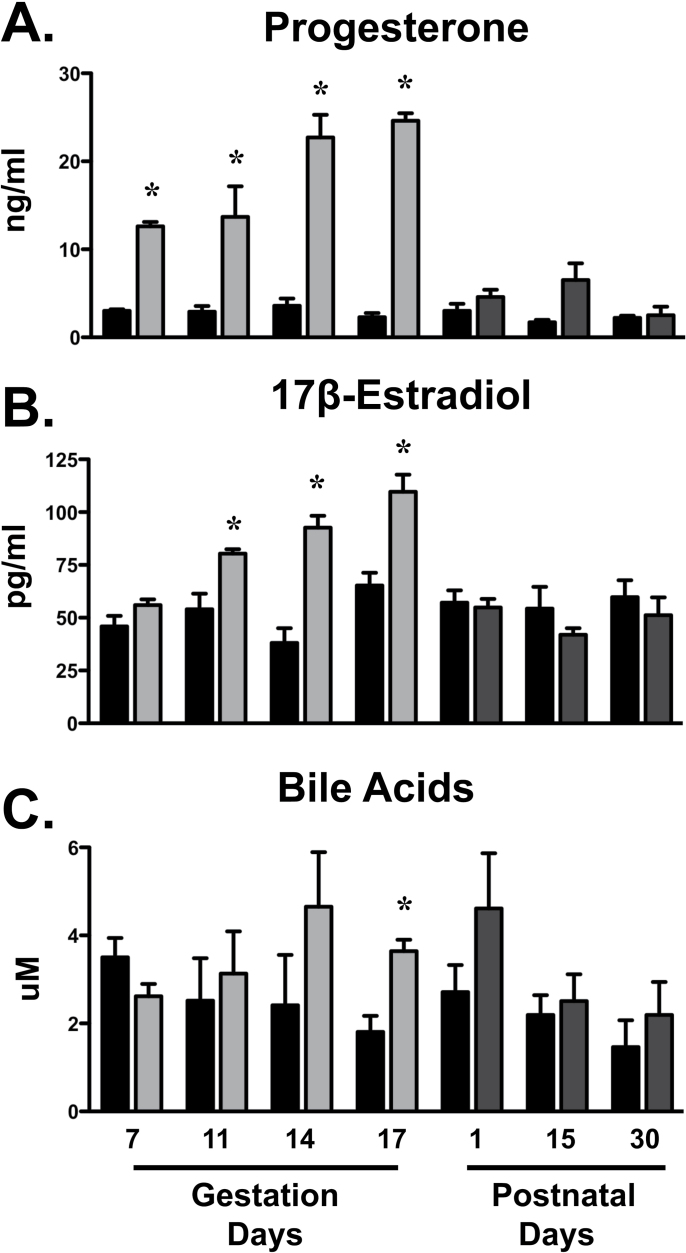

Serum Progesterone, Estradiol, and Bile Acids in Pregnant and Lactating Mice

Serum elevations in progesterone were observed as early as GD7 and reached maximal levels between GD14 and 17 (10-fold increase) (Fig. 8). Estradiol concentrations were enhanced in pregnant dams between GD11 and 17. In addition, serum bile acid levels tended to increase on GD14 and were doubled on GD17. Following parturition, progesterone and estradiol levels returned to virgin control levels. On PND1, concentrations of bile acids were increased 70% although not statistically significant. By PND15, bile acid concentrations were similar in dams and virgin control mice.

FIG. 8.

Serum hormone levels in pregnant and lactating mice Levels of progesterone (A), 17β-estradiol (B), and total bile acids (C) were quantified in serum from virgin and pregnant mice on GD7, 11, 14, and 17 and PND1, 15, and 30. Black bars represent virgin mice, light gray bars represent pregnant mice, and dark gray bars represent lactating mice. Data are presented as mean ± SE. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) compared with time-matched virgin mice.

Hepatic Transcription Factor–Related Pathways in Pregnant and Lactating Mice

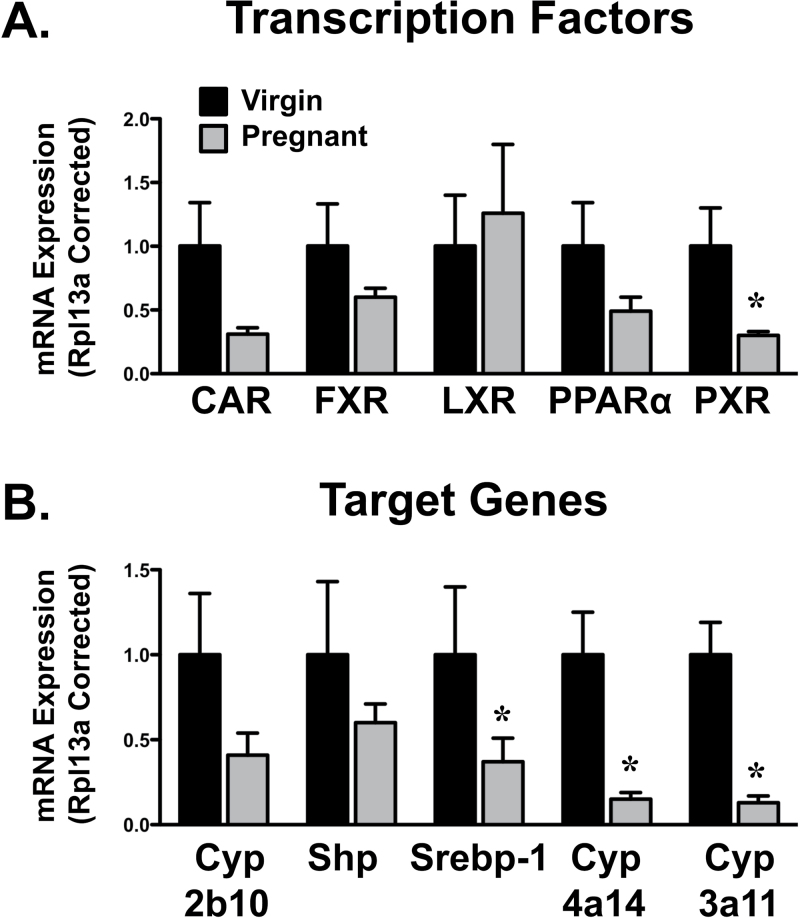

Transcription factors known to regulate transporter expression were quantified on GD14 when most gene changes were observed (Fig. 9A). PXR mRNA decreased 70% in pregnant dams. Similarly, there was a trend for reduced levels of CAR (p = 0.06), FXR, and PPARα in livers of pregnant mice. LXR mRNA was unchanged. Levels of the estrogen receptor alpha were increased 100% in pregnant mice on GD14 (data not shown).

FIG. 9.

Hepatic mRNA expression of transcription factor–related pathways in pregnant mice. mRNA expression of transcription factors (A) and prototypical genes (B) was quantified using total hepatic RNA from virgin and pregnant mice on GD14. Data were normalized to matched virgin controls (set to 1.0) and presented as mean relative expression ± SE. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) compared to time-matched virgin mice. It should be noted that the statistical analysis revealed a value of p = 0.06 for CAR mRNA.

Compared with virgin mice, target genes of transcription factors were also reduced during pregnancy (Fig. 9B). Srebp-1, Cyp4a14, and Cyp3a11, which are target genes of LXR, PPARα, and PXR, respectively, were decreased 60–85% in pregnant mice. Expression of the CAR and FXR target genes, Cyp2b10 and Shp, was also reduced although not statistically significant. Expression of the oxidative stress sensor Nrf2 and its target gene, NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1, was not altered during pregnancy (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the time-dependent regulation of hepatobiliary transporters and bile acid metabolism genes during pregnancy and lactation in mice. Pregnancy caused a global downregulation of most transporters, which began as early as GD7 for some genes and was maximal by GD14 and 17 (Table 1). The decreasing expression of transporters with the progression of pregnancy was inversely related to increasing concentrations of circulating 17β-estradiol and progesterone. Downregulation of Ntcp, some Oatps, and Mrp3 at the mRNA and protein levels is consistent with prior studies (Arrese et al., 2003; Cao et al., 2002; Milona et al., 2010). However, this is the first report of pregnancy-induced changes in Oat2, Oct1, Ent1, Mrp4, and Mate1 mRNA in livers of mice. Likewise, the upregulation of the classic bile acid synthesis genes, Cyp7a1 and 8b1, has been previously reported (He et al., 2007; Milona et al., 2010). In contrast, there has been little investigation of alternative and conjugating bile acid pathways during pregnancy. The elevated levels of serum bile acids during the end of pregnancy are likely a result of downregulation of uptake transporters, increased expression of classic pathway synthesis genes, and reduced mRNA levels of bile acid conjugating enzymes. It is difficult to determine the exact contribution of each of these pathways to the increased bile acid levels during pregnancy; however, their functional importance can be hypothesized based upon phenotypic changes in mice lacking key enzymes or transporters. For example, the genetic knockout of Cyp7a1 in mice can decrease fecal bile acids (Erickson et al., 2003; Wolters et al., 2002). Conversely, mice lacking Bsep have elevated circulating levels of bile acids (Zhang et al., 2012). The decreased expression of alternative bile acid genes may be an adaptive response to counterbalance the increased levels of bile acids.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Transporter and Bile Acid mRNA Changes in Mice During Pregnancy and Lactationa

| Gestation | Lactation | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | Days | |||||||||||||

| 7 | 11 | 14 | 17 | 1 | 15 | 30 | ||||||||

| Uptake | ||||||||||||||

| Ntcp | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Oatp1a1 | — | — | — | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Oatp1a4 | — | — | — | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Oatp1b2 | — | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | |||||||

| Oatp2b1 | — | — | — | — | ↓↓ | — | — | |||||||

| Oat2 | — | — | ↑↑ | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| Oct1 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | |||||||

| Ent1 | — | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Canalicular efflux | ||||||||||||||

| Bsep | — | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Mrp2 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | |||||||

| Bcrp | ↓↓ | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | |||||||

| Mdr2 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | |||||||

| Abcg5 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Abcg8 | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | |||||||

| Atp8b1 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | |||||||

| Mate1 | — | — | ↓↓ | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| Basolateral efflux | ||||||||||||||

| Mrp3 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Mrp4 | — | ↑↑ | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| Mrp6 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | |||||||

| Abca1 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| Bile acids | ||||||||||||||

| Cyp7a1 | — | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Cyp7b1 | — | — | — | — | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | — | |||||||

| Cyp8b1 | — | — | — | ↑↑ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Cyp27a1 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Cyp39a1 | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Bal | — | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | — | — | — | |||||||

| Baat | — | — | ↓↓ | — | — | — | — | |||||||

aStatistically significant changes are designated as ↑↑ or ↓↓ compared with virgin controls at each time point. Dashes denote no statistical change.

A number of efflux transporter genes begin to decline by GD7 to 11. In general, most uptake transporter mRNA decreased by GD11, which may be a response to limit cellular accumulation of chemicals secondary to impaired efflux. General retention of substances in the circulation (reduced uptake) or in the liver (reduced efflux) may be a mechanism to prevent excretion of nutrients needed for fetal development and maternal energy. There could be consequences of reduced biliary circulation of bile acids. For example, reduced enterohepatic recirculation of bile acids may impair the absorption of vitamins in the intestine during a time when the nutritional demands of the dam are greatest. Therefore, future investigations should systematically assess transporter expression in the intestines of rodents during pregnancy. For example, Mottino et al. (2002) have demonstrated increased intestinal expression of the apical bile acid transporter Asbt in the ileum during the postpartum period and suggested that this adaptive change could improve the retention of bile acids within the body. Additional work from the same group demonstrates unchanged intestinal Mrp2 expression of rats during pregnancy with induction during lactation (Mottino et al., 2001). Because Mrp2 is localized to the apical surface of enterocytes, it has been proposed that upregulation of Mrp2 after parturition may be a mechanism to prevent systemic absorption of dietary toxins into lactating dams.

It should be noted that two transporters, Oat2 and Mrp4, were modestly increased during pregnancy. Although the exact mechanism responsible for these changes is unclear, it can be hypothesized that elevated sex hormones may increase their expression. For example, Oat2 mRNA is modestly inducible in rat kidneys by exogenous estradiol and progesterone treatment (Ljubojević et al., 2007). This is supported by increased estrogen receptor alpha mRNA expression in the livers of pregnant mice on GD14 (data not shown). Because progesterone can functionally inhibit Mrp4 activity (Wielinga et al., 2003), upregulation of Mrp4 mRNA and protein may counteract this inhibition. However, further studies are needed to determine whether the concentrations of progesterone observed in pregnant mice (Fig. 8) can impair Mrp4 function in vivo. Although there is some evidence to support this speculation, additional work is necessary to definitively determine the mechanisms underlying Oat2 and Mrp4 upregulation during pregnancy.

Additional work in our laboratory demonstrates downregulation of phase II glucuronidation and glutathione conjugation genes in pregnant mice (data not shown). Reduced formation of glucuronide and glutathione conjugates parallels the decline in transporters that are responsible for their extrusion including Mrp3 (Akita et al., 2002; Hirohashi et al., 1999; Keppler et al., 1997, 1998; Müller et al., 1996). Alternatively, expression of sulfotransferase enzymes and sulfonation activity is enhanced in livers of mice during pregnancy, which may be an additional reason why Mrp4 mRNA is upregulated, because this transporter participates in the efflux of sulfate conjugates to sinusoidal blood (Zelcer et al., 2003).

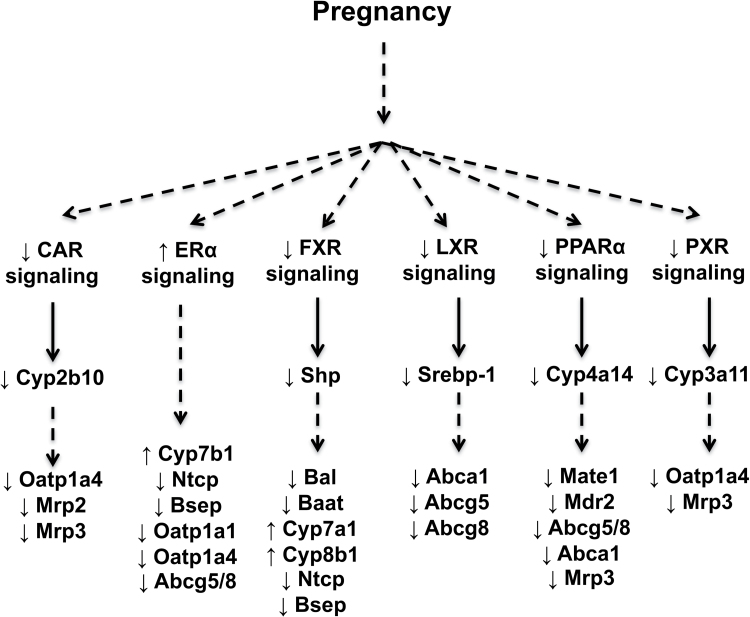

Similar to prior reports (Koh et al., 2011; Sweeney et al., 2006), the expression of a number of nuclear receptors was reduced in livers of pregnant mice in the present study (Figs. 9 and 10). Most notable was the downregulation of the LXR, PPARα, and PXR signaling pathways. There were also trends for reduced activity of CAR and FXR signaling similar to the downregulation previously reported in rodent livers (He et al., 2007; Milona et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2008), although large variability in time-matched virgin levels prevented the detection of statistical differences. In most cases, the mRNA of each transcription factor and its target gene were reduced. In the case of LXR, its mRNA was unchanged, whereas its target gene Srebp1 was markedly reduced. Prior studies demonstrate the ability of LXR to regulate Abca1, Abcg5, and Abcg8 (Repa et al., 2002) and support the downregulation of these genes as a consequence of impaired LXR signaling during pregnancy. Likewise, PPARα can also regulate these genes in coordination with LXR (Kok et al., 2003b) and may contribute to their downregulation, as well as Mate1 (data not shown), Mdr2 (Kok et al., 2003a), and Mrp3 (Moffit et al., 2006). Although the declines in FXR and Shp mRNA were not statistically significant, Milona et al. (2010) have suggested that pregnancy is a condition of impaired FXR signaling that leads to increased Cyp7a1 and 8b1 mRNA. Reduced expression of Bsep, Ntcp, Bal, and Baat could also be the direct or indirect result of altered FXR signaling (Ananthanarayanan et al., 2001; Gerloff et al., 2002; Milona et al., 2010; Pircher et al., 2003). In addition, downregulation of CAR and PXR signaling may coordinately reduce levels of Oatp1a4 and Mrp3 mRNA (Cheng et al., 2005; Maher et al., 2005; Stedman et al., 2005).

FIG. 10.

Proposed signaling pathways regulating transporter and bile acid gene expression during pregnancy. Pregnancy elevates levels of sex hormones and bile acids, which may be involved in the global downregulation of multiple transcription factors as demonstrated in the current and previous studies (Koh et al., 2011; Sweeney et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2006). Target genes were decreased or tended to be reduced for each transcription factor, which provides potential mechanisms for the differential expression of transporter and bile acid genes in the livers of mice during pregnancy.

Activation of ERα during pregnancy could also be involved in the repression of hepatobiliary transporters. Administration of repeated hepatotoxic doses of 17α-ethinylestradiol to wild-type mice causes hepatomegaly and hepatocyte degeneration, which are not observed in ERα-null mice (Yamamoto et al., 2006). In addition, 17α-ethinylestradiol toxicity was associated with downregulation of Bsep, Ntcp, Oatp1a1 and 1a4, as well as Abcg5 and 8 mRNA that was ERα-dependent. It was also demonstrated that reduced transporter mRNA expression was not due to FXR, CAR, or PXR in male mice (Yamamoto et al., 2006). It is possible that ERα participates in transporter downregulation during normal pregnancies; however, extrapolation of the findings from a hepatotoxicity study of 17α-ethinylestradiol should be done cautiously.

The precise mechanism responsible for downregulation of numerous nuclear receptors is unclear. There is the potential for sex hormones, such as 17β-estradiol, to directly alter nuclear receptor function as suggested for FXR (Milona et al., 2010) or to downregulate transcription of nuclear receptor mRNA as observed for PPARα (Jeong and Yoon, 2007). An alternate explanation could be that elevated levels of endogenous ligands such as bile acids, oxysterols, and triglycerides during pregnancy initiate a compensatory downregulation of their receptors. There is also the potential for global regulation of nuclear receptors by upstream liver-specific transcription factors including hepatocyte nuclear factors (HNF). mRNA levels of HNF 1α, 4α, and 1b were unchanged, whereas HNF3α was reduced in a separate study of pregnant mice on GD14 (data not shown). Future studies should also consider other signaling pathways including HNF3α, Sp1, and STAT proteins, which are capable of coordinately regulating large gene networks in the liver (Leuenberger et al., 2009).

In conclusion, there is a global decline in expression of uptake and efflux transporters in the livers of pregnant mice, similar to what has been reported for rats. In addition, two liver transporters Oat2 and Mrp4 are modestly increased during pregnancy. Additional analysis suggests that elevated bile acids during late pregnancy are due to increased mRNA expression of classic bile acid synthesis enzymes rather than alternative pathway enzymes. These findings are compelling and suggest that the liver reduces hepatobiliary excretion as pregnancy progresses, possibly to retain nutrients or to compensate for increases in hepatic perfusion. Translational studies are needed to better understand whether human livers demonstrate similar changes in the expression of hepatobiliary transport genes. Nonetheless, the fact that developmental toxicology studies are frequently performed in rodents and rabbits, these data provide novel information that can be used to better interpret data from in vivo studies during pregnancy.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK080774, DK081461); National Institutes of Health Environmental Health Sciences (ES019487, ES020522, ES009649, ES007079); National Center for Research Resources (RR021940), a component of the National Institutes of Health; NIEHS sponsored UMDNJ Center for Environmental Exposures and Disease (NIEHS P30ES005022).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for antibodies provided by Dr Bruno Stieger (University of Zurich, Switzerland) and Dr George Scheffer (VU Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The authors would like to thank Dr Belén Tornesi and Dr Brian Enright for critical review of the manuscript, and the graduate students and fellows of the Klaassen laboratory for contributions to this project.

REFERENCES

- Akita H., Suzuki H., Hirohashi T., Takikawa H., Sugiyama Y. (2002). Transport activity of human MRP3 expressed in Sf9 cells: Comparative studies with rat MRP3. Pharm. Res. 19 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksunes L. M., Slitt A. L., Maher J. M., Augustine L. M., Goedken M. J., Chan J. Y., Cherrington N. J., Klaassen C. D., Manautou J. E. (2008). Induction of Mrp3 and Mrp4 transporters during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity is dependent on Nrf2. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 226 74–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthanarayanan M., Balasubramanian N., Makishima M., Mangelsdorf D. J., Suchy F. J. (2001). Human bile salt export pump promoter is transactivated by the farnesoid X receptor/bile acid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 276 28857–28865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. D. (2005). Pregnancy-induced changes in pharmacokinetics: A mechanistic-based approach. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 44 989–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrese M., Trauner M., Ananthanarayanan M., Pizarro M., Solís N., Accatino L., Soroka C., Boyer J. L., Karpen S. J., Miquel J. F., et al. (2003). Down-regulation of the Na+/taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide during pregnancy in the rat. J. Hepatol. 38 148–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigi R. H., Han K., Venkataramanan R., Hankins G. D., Clark S., Hebert M. F., Easterling T., Zajicek A., Ren Z., Mattison D. R., et al. (2011). Pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir among pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 204(6 Suppl 1)S84–S88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Huang L., Liu Y., Hoffman T., Stieger B., Meier P. J., Vore M. (2001). Differential regulation of hepatic bile salt and organic anion transporters in pregnant and postpartum rats and the role of prolactin. Hepatology 33 140–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Stieger B., Meier P. J., Vore M. (2002). Expression of rat hepatic multidrug resistance-associated proteins and organic anion transporters in pregnancy. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 283 G757–G766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Yang K., Choi S., Fischer J. H., Jeong H. (2009). Up-regulation of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A4 by 17beta-estradiol: A potential mechanism of increased lamotrigine elimination in pregnancy. Drug Metab. Dispos. 37 1841–1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Maher J., Dieter M. Z., Klaassen C. D. (2005). Regulation of mouse organic anion-transporting polypeptides (Oatps) in liver by prototypical microsomal enzyme inducers that activate distinct transcription factor pathways. Drug Metab. Dispos. 33 1276–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens A. J., Risler L. J., Eyal S., Shen D. D., Easterling T. R., Hebert M. F. (2010). CYP2D6 mediates 4-hydroxylation of clonidine in vitro: Implication for pregnancy-induced changes in clonidine clearance. Drug Metab. Dispos. 38 1393–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanaky I. L., Aleksunes L. M., Tanaka Y., Klaassen C. D. (2009). Role of hepatic transporters in prevention of bile acid toxicity after partial hepatectomy in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 297 G419–G433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J. Y., Aleksunes L. M., Tanaka Y., Fu Z. D., Guo Y., Guo G. L., Lu H., Zhong X. B., Klaassen C. D. (2012). Bile acids via FXR initiate the expression of major transporters involved in the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids in newborn mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 302 G979–G996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw J. R., Hanley G. E., Greyson D. L., Morgan S. G. (2011). Prescription drug use during pregnancy in developed countries: A systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 20 895–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon P. H., van Mil S. W., Chambers J., Strautnieks S., Thompson R. J., Lammert F., Kubitz R., Keitel V., Glantz A., Mattsson L. A., et al. (2009). Contribution of variant alleles of ABCB11 to susceptibility to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gut 58 537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson S. K., Lear S. R., Deane S., Dubrac S., Huling S. L., Nguyen L., Bollineni J. S., Shefer S., Hyogo H., Cohen D. E., et al. (2003). Hypercholesterolemia and changes in lipid and bile acid metabolism in male and female cyp7A1-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 44 1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyal S., Easterling T. R., Carr D., Umans J. G., Miodovnik M., Hankins G. D., Clark S. M., Risler L., Wang J., Kelly E. J., et al. (2010). Pharmacokinetics of metformin during pregnancy. Drug Metab. Dispos. 38 833–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. P., Nolan P. E., Jr, Davis M. F., Anthony M., Fried K., Fankhauser M., Woosley R. L., Moreno F. (2008). Pharmacokinetics of sertraline across pregnancy and postpartum. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 28 646–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff T., Geier A., Roots I., Meier P. J., Gartung C. (2002). Functional analysis of the rat bile salt export pump gene promoter. Eur. J. Biochem. 269 3495–3503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D. P., Klaassen C. D. (2000). Detection of chemical-induced differential expression of rat hepatic cytochrome P450 mRNA transcripts using branched DNA signal amplification technology. Drug Metab. Dispos. 28 608–616 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. J., Yamauchi H., Suzuki K., Ueno M., Nakayama H., Doi K. (2007). Gene expression profiles of drug-metabolizing enzymes (DMEs) in rat liver during pregnancy and lactation. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 83 428–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert M. F., Easterling T. R., Kirby B., Carr D. B., Buchanan M. L., Rutherford T., Thummel K. E., Fishbein D. P., Unadkat J. D. (2008). Effects of pregnancy on CYP3A and P-glycoprotein activities as measured by disposition of midazolam and digoxin: A University of Washington specialized center of research study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 84 248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen J., Mäentausta O., Ylöstalo P., Jänne O. (1981). Changes in serum bile acid concentrations during normal pregnancy, in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and in pregnant women with itching. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 88 240–245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirohashi T., Suzuki H., Sugiyama Y. (1999). Characterization of the transport properties of cloned rat multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 (MRP3). J. Biol. Chem. 274 15181–15185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S., Yoon M. (2007). Inhibition of the actions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha on obesity by estrogen. Obesity (Silver Spring). 15 1430–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler D., König J., Büchler M. (1997). The canalicular multidrug resistance protein, cMRP/MRP2, a novel conjugate export pump expressed in the apical membrane of hepatocytes. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 37 321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler D., Leier I., Jedlitschky G., König J. (1998). ATP-dependent transport of glutathione S-conjugates by the multidrug resistance protein MRP1 and its apical isoform MRP2. Chem. Biol. Interact. 111-112 153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klier C. M., Mossaheb N., Saria A., Schloegelhofer M., Zernig G. (2007). Pharmacokinetics and elimination of quetiapine, venlafaxine, and trazodone during pregnancy and postpartum. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 27 720–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutti R., Rothweiler H., Schlatter C. (1981). Effect of pregnancy on the pharmacokinetics of caffeine. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 21 121–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh K. H., Xie H., Yu A. M., Jeong H. (2011). Altered cytochrome P450 expression in mice during pregnancy. Drug Metab. Dispos. 39 165–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok T., Bloks V. W., Wolters H., Havinga R., Jansen P. L., Staels B., Kuipers F. (2003a). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha)-mediated regulation of multidrug resistance 2 (Mdr2) expression and function in mice. Biochem. J. 369(Pt 3), 539–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok T., Wolters H., Bloks V. W., Havinga R., Jansen P. L., Staels B., Kuipers F. (2003b). Induction of hepatic ABC transporter expression is part of the PPARalpha-mediated fasting response in the mouse. Gastroenterology 124 160–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laatikainen T., Ikonen E. (1977). Serum bile acids in cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 50 313–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuenberger N., Pradervand S., Wahli W. (2009). Sumoylated PPARalpha mediates sex-specific gene repression and protects the liver from estrogen-induced toxicity in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119 3138–3148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubojević M., Balen D., Breljak D., Kusan M., Anzai N., Bahn A., Burckhardt G., Sabolić I. (2007). Renal expression of organic anion transporter OAT2 in rats and mice is regulated by sex hormones. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 292 F361–F372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquita M. G., Catania V. A., Pozzi E. J., Veggi L. M., Hoffman T., Pellegrino J. M., Ikushiro Si, Emi Y., Iyanagi T., Vore M., et al. (2001). Molecular basis of perinatal changes in UDP-glucuronosyltransferase activity in maternal rat liver. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298 49–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher J. M., Cheng X., Slitt A. L., Dieter M. Z., Klaassen C. D. (2005). Induction of the multidrug resistance-associated protein family of transporters by chemical activators of receptor-mediated pathways in mouse liver. Drug Metab. Dispos. 33 956–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milona A., Owen B. M., Cobbold J. F., Willemsen E. C., Cox I. J., Boudjelal M., Cairns W., Schoonjans K., Taylor-Robinson S. D., Klomp L. W., et al. (2010). Raised hepatic bile acid concentrations during pregnancy in mice are associated with reduced farnesoid X receptor function. Hepatology 52 1341–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffit J. S., Aleksunes L. M., Maher J. M., Scheffer G. L., Klaassen C. D., Manautou J. E. (2006). Induction of hepatic transporters multidrug resistance-associated proteins (Mrp) 3 and 4 by clofibrate is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 317 537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottino A. D., Hoffman T., Jennes L., Cao J., Vore M. (2001). Expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 in small intestine from pregnant and postpartum rats. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280 G1261–G1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottino A. D., Hoffman T., Dawson P. A., Luquita M. G., Monti J. A., Sánchez Pozzi E. J., Catania V. A., Cao J., Vore M. (2002). Increased expression of ileal apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter in postpartum rats. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver. Physiol. 282, G41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M., de Vries E. G., Jansen P. L. (1996). Role of multidrug resistance protein (MRP) in glutathione S-conjugate transport in mammalian cells. J. Hepatol. 24(Suppl. 1)100–108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli-Magnus C., Meier P. J., Stieger B. (2010). Genetic determinants of drug-induced cholestasis and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Semin. Liver Dis. 30 147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pircher P. C., Kitto J. L., Petrowski M. L., Tangirala R. K., Bischoff E. D., Schulman I. G., Westin S. K. (2003). Farnesoid X receptor regulates bile acid-amino acid conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 278 27703–27711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa J. J., Berge K. E., Pomajzl C., Richardson J. A., Hobbs H., Mangelsdorf D. J. (2002). Regulation of ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8 by the liver X receptors alpha and beta. J. Biol. Chem. 277 18793–18800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salman S. Rogerson S. J. Kose K. Griffin S. Gomorai S. Baiwog F. Winmai J. Kandai J. Karunajeewa H. A. O’Halloran S. J. et al. (2010). Pharmacokinetic properties of azithromycin in pregnancy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 360–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sookoian S., Castaño G., Burgueño A., Gianotti T. F., Pirola C. J. (2008). Association of the multidrug-resistance-associated protein gene (ABCC2) variants with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J. Hepatol. 48 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stedman C. A., Liddle C., Coulter S. A., Sonoda J., Alvarez J. G., Moore D. D., Evans R. M., Downes M. (2005). Nuclear receptors constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor ameliorate cholestatic liver injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 2063–2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney T. R., Moser A. H., Shigenaga J. K., Grunfeld C., Feingold K. R. (2006). Decreased nuclear hormone receptor expression in the livers of mice in late pregnancy. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 290 E1313–E1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mil S. W., Milona A., Dixon P. H., Mullenbach R., Geenes V. L., Chambers J., Shevchuk V., Moore G. E., Lammert F., Glantz A. G., et al. (2007). Functional variants of the central bile acid sensor FXR identified in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology 133 507–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wu X., Hudkins K., Mikheev A., Zhang H., Gupta A., Unadkat J. D., Mao Q. (2006). Expression of the breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp1/Abcg2) in tissues from pregnant mice: Effects of pregnancy and correlations with nuclear receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 291 E1295–E1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielinga P. R., van der Heijden I., Reid G., Beijnen J. H., Wijnholds J., Borst P. (2003). Characterization of the MRP4- and MRP5-mediated transport of cyclic nucleotides from intact cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278 17664–17671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters H., Elzinga B. M., Baller J. F., Boverhof R., Schwarz M., Stieger B., Verkade H. J., Kuipers F. (2002). Effects of bile salt flux variations on the expression of hepatic bile salt transporters in vivo in mice. J. Hepatol. 37 556–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Moore R., Hess H. A., Guo G. L., Gonzalez F. J., Korach K. S., Maronpot R. R., Negishi M. (2006). Estrogen receptor alpha mediates 17alpha-ethynylestradiol causing hepatotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 281 16625–16631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelcer N., Reid G., Wielinga P., Kuil A., van der Heijden I., Schuetz J. D., Borst P. (2003). Steroid and bile acid conjugates are substrates of human multidrug-resistance protein (MRP) 4 (ATP-binding cassette C4). Biochem. J. 371(Pt 2)361–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Wu X., Wang H., Mikheev A. M., Mao Q., Unadkat J. D. (2008). Effect of pregnancy on cytochrome P450 3a and P-glycoprotein expression and activity in the mouse: Mechanisms, tissue specificity, and time course. Mol. Pharmacol. 74 714–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li F., Patterson A. D., Wang Y., Krausz K. W., Neale G., Thomas S., Nachagari D., Vogel P., Vore M., et al. (2012). Abcb11 deficiency induces cholestasis coupled to impaired beta-fatty acid oxidation in mice J. Biol. Chem. 287, 24784–24794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang H., Unadkat J. D., Mao Q. (2007). Breast cancer resistance protein 1 limits fetal distribution of nitrofurantoin in the pregnant mouse. Drug Metab. Dispos. 35 2154–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Naraharisetti S. B., Wang H., Unadkat J. D., Hebert M. F., Mao Q. (2008). The breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp1/Abcg2) limits fetal distribution of glyburide in the pregnant mouse: An Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit Network and University of Washington Specialized Center of Research Study. Mol. Pharmacol. 73 949–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.