Abstract

Context:

Suicidal ideation in depressed patients is a serious and emergent condition that requires urgent intervention. Intravenous ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, has shown rapid antidepressant effects, making it a potentially attractive candidate for depressed patients with suicidal risk.

Aims:

In India few studies have corroborated such findings; the present study aimed to assess the effectiveness and sustainability of antisuicidal effects of ketamine in subjects with resistant depression.

Settings and Design:

Single-center, prospective, 4 weeks, open-label, single-arm pilot study.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-seven subjects with DSM-IV major depression (treatment resistant) were recruited. The subjects were assessed on Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI), 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). After a 2-week drug-free period, subjects were given a single intravenous infusion of ketamine hydrochloride (0.5 mg/kg) and were rated at baseline and at 40, 80, 120, and 230 minutes and 1 and 2 days postinfusion.

Results:

The ketamine infusion was effective in reducing the SSI and HDRS scores, the change remained significant from minute 40 to 230 at each time point.

Conclusions:

The real strength of this study rests in documenting the rapid albeit short-lasting effect of ketamine on suicidal ideation in depressed patients.

Keywords: Glutamate, ketamine, suicidal cognition, treatment-resistant depression

INTRODUCTION

Vast majority of psychiatric patients who display suicidal behavior have major depressive disorder (MDD). Severity of depression has thus been associated with more suicide attempts. Among the enrolees in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, 16.5% reported previous suicide attempts.[1]

Suicidal ideation in patients with MDD is a serious and emergent clinical condition that mandates immediate attention and treatment. A recent study of patients who attempted suicide found that 74% said the decision-making period (i.e., the period between decision and attempt) was very short.[2] Though the identification of risk factors is key to suicide prevention, one crucial factor regards the timing of suicidal behavior.

Numerous studies have found that individuals with affective disorders are at greatest risk of death from any cause, including suicide, in the first 2 years after their diagnosis.[3] More specifically, studies have consistently identified the emergency room, the inpatient unit, time after discharge, and time after initiating an antidepressant as time points where individuals are particularly vulnerable to suicidal ideation.[4–7]

In clinical practice these circumstances offer the possibility to intervene quickly and decisively to prevent suicidal behavior. Current therapeutic options for severe mood disorders are limited by the slow time course of change in suicidal thoughts. For instance, in major depressive disorder (MDD) patients receiving thrice-weekly electroconvulsive therapy, suicidal thoughts persisted in 62% of patients after 1 week of treatment and 39% after 2 weeks.[8] Furthermore, conventional antidepressants may produce slower and less robust response in patients with moderate to high suicide risk than in nonsuicidal patients.[9]

Various therapeutic interventions to reduce suicide risk in serious psychiatric disorders are effective in long-term suicide prevention - most notably lithium for the treatment of bipolar disorder[10] and, to a lesser extent, MDD,[11] as well as the atypical antipsychotic clozapine in schizophrenia.[12]

Recent evidence suggests that a single subanesthetic dose of intravenous (IV) ketamine, a glutamate-modulating agent, acutely reduces depressive symptoms in approximately 70% of MDD patients 24 hours after infusion.[13]

Despite advances in psychopharmacology, the acute pharmacological management of suicidal risk in MDD remains comparatively underinvestigated.[14]

Thus, it appears that agents targeting the glutamatergic system may be key to developing a new generation of improved treatments for this devastating condition.

In India till date very few studies have corroborated such findings, the present study aimed to assess the efficacy and sustainability of antisuicidal effects of ketamine in subjects with treatment resistant MDD (TRD).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This present study was a single center, prospective, 4-week, open-label, single-arm pilot study to assess the clinical utility and efficacy of single subanesthetic infusion of ketamine on suicidal ideation.

Twenty-seven patients aged 18-65 years participated in this study between February 2011 and November 2011. Participants fulfilled the criteria for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) for MDD (treatment resistant). Treatment resistance was defined as two or more failed, adequate antidepressant trials in the current episode, as determined by the Antidepressant Treatment History Form.[15] DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of MDD were established by Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P).[16]

Subjects were psychotropic medication-free for 2 weeks before infusion (4 weeks for fluoxetine); were free of substance abuse/dependence for 6 months; denied lifetime use of ketamine and phencyclidine (PCP); had no lifetime history of psychotic disorder, mania, or hypomania; and had no clinically unstable medical or neurological conditions. All subjects were in good physical health as determined by medical history, complete physical examination, blood laboratory results, electrocardiogram, chest radiography, and urinalysis and toxicology findings. Subjects had a negative urine toxicology screen. Patients received a complete description of the study, and written informed consent was subsequently obtained.

The study was approved by the Institutional ethics committee and was carried out in psychiatry critical care unit of a tertiary teaching hospital having major drainage from urban areas and nearby industrial townships.

Patients were kept under continuous observation by psychiatrists during the entire study period. Patients were admitted to hospital and received a single infusion racemic ketamine hydrochloride (0.5 mg/kg diluted in 0.9% saline, administered over 40 minutes) by IV pump by an anesthesiologist and kept under continuous cardio respiratory monitoring. Subjects were rated 60 minutes prior to the infusion (baseline) and at 40, 80, 120, and 230 minutes, as well as 1 and 2 days postinfusion. Rating scales included the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS),[17] HDRS-suicidality item (HDRS-SI), the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI).[18] Previous studies have identified a cut-off score >3 as indicating significant suicidal ideation on the SSI; and without significant suicidal ideation (SSI <4) at baseline.[19] Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; a positive-symptom subscale), which was used.[20] All items on each scale were used. There were no dropouts from the study.

RESULTS

Data were described using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significant effects were examined with simple effect tests. Within group analysis of change of HDRS scores and SSI over time was compared to baseline using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. Significance was evaluated at P<0.05.

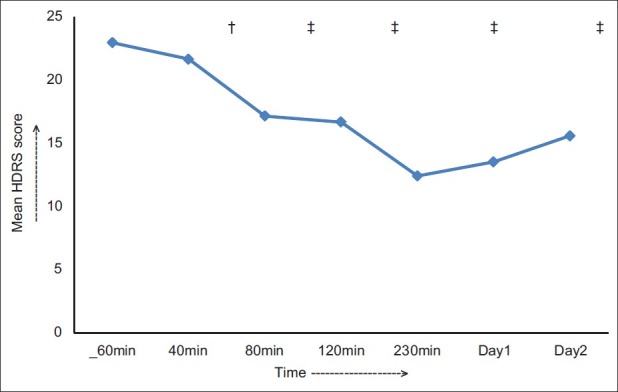

Table 1 describes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects participating in the study. The overall sample (n=27) had a mean±SD age of 49.44±8.10 years. The sample had 14 women and 13 men, with a mean body weight of 63.44 kg; 30.8% had a lifetime diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence. The mean±SD length of illness was 24.22±10.81 years, and the mean±SD of current depressive episode was 23.6±21.5 months. The mean number of previous depressive episodes was 6.5. Five patients had previously received electroconvulsive therapy. All subjects had adequate antidepressant trials for the current major depressive episode.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

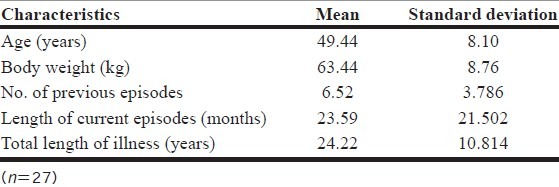

To study the effect of ketamine on suicidal ideation (SSI scores) the repeated measures analysis of variance with Huynh-Feldt correction was applied as the sphericity assumption was not met. The ketamine infusion was effective in reducing the SSI scores, and the main effect of time measurement was significant, F (1.29, 33.58)=17.29, P<0.001, partial eta squared=0.4. Mean±SD scores declined by four points from baseline (4.85± 5.37) to 40 minutes postinfusion (0.78±1.48; P=0.001). The change remained significant from minute 40 to minute 230 postinfusion at each time point. The maximum change was detected at 40 minutes (0.78±1.48; P=0.001), with more than 80% change over baseline. The change was not significant from day 1 onward, with scores approaching baseline by day 2 (4.41±4.8; P=0.534). Figure 1 depicts the change in mean SSI scores over time.

Figure 1.

The change in the mean SSI score scores over time, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.001

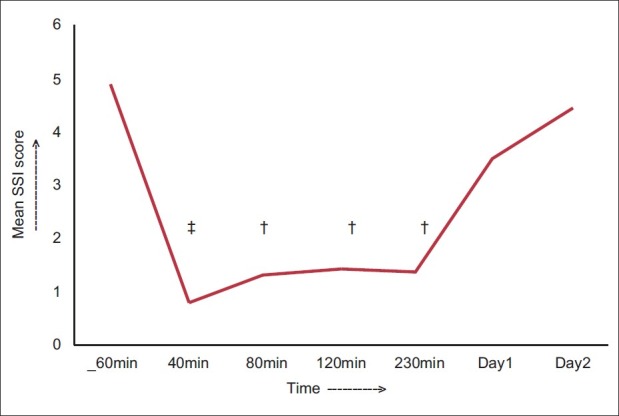

Figure 2 shows the change in HDRS-SI (suicide- subscale) scores over time. There was significant improvement following ketamine infusion F (1.97, 51.09)=15.57, P<0.001 partial eta squared=0.38. Post hoc results reveal that the change was significant from 40 minutes to 230 minutes postinfusion. Compared to baseline scores (1.37±1.33) maximum reduction in scores was at 40 minutes (0.41±0.57, P=0.001) with more than 70% reduction. The change was not significant from day 1 onward.

Figure 2.

The change in the mean HDRS SI scores over time, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.001

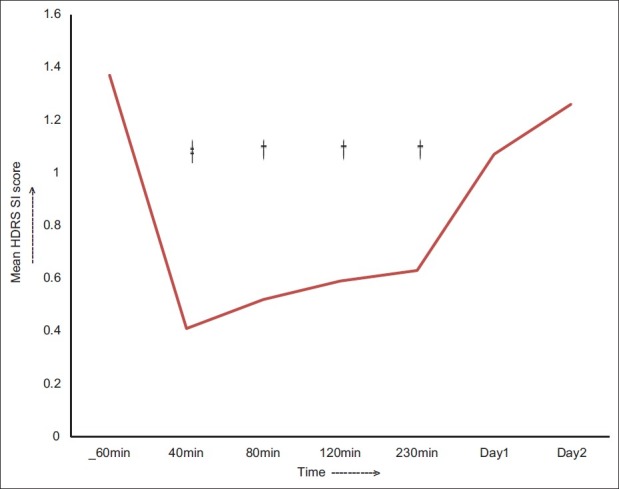

The ketamine infusion was effective in reducing the HDRS scores, and the main effect of time measurement was significant F (2.14, 55.69)=124.65; P<0.001, partial eta squared=0.83. Mean±SD HDRS scores declined by 6 points from baseline (22.96±1.2) to 80 minutes postinfusion (17.5±5.34) (P<0.01). The change remained significant from minute 80 to day 2 postinfusion at each time point. The maximum change was detected at 230 minutes (12.41±3.38; P< 0.001), with more than 45% change over baseline. The change remained significant up to day 2 (15.6±4.64; P<0.001). Figure 3 depicts the change in mean HDRS scores over time.

Figure 3.

The change in the mean HDRS scores over time, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.001

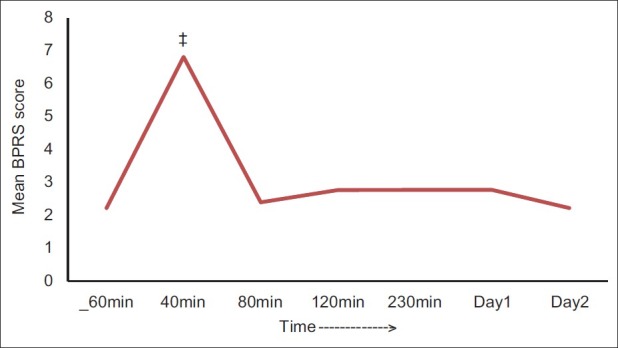

Figure 4 shows the change in BPRS (a positive-symptom subscale) scores over time. Post hoc results reveal that the change was significant only at 40 minutes postinfusion compared with baseline scores (P<0.001) and was not statistically significant any time after that.

Figure 4.

The change in the mean BPRS scores over time, ‡P<0.001

Adverse effects such as elevated blood pressure, euphoria, headache, increased thirst, and dizziness occurring with ketamine administration ceased within 60 minutes. No serious adverse events occurred during the study.

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of this open-label study conducted in Indian subjects was that that a single low dose of IV ketamine has speedy effects on suicidal cognition in TRD. This study found that ketamine induced a rapid and dramatic response in ameliorating suicidal ideation in the context of MDD, which was statistically significant from minute 40 to minute 230 postinfusion but was relatively ill-sustained, with score change not being statistically significant from day 1 onward compared with baseline scores.

Several therapeutic interventions to reduce suicide risk in major psychiatric disorders are effective in long-term suicide prevention, most notably lithium for the treatment of bipolar disorder[10] and, to a lesser extent, MDD.[11] With regard to second-generation antipsychotic drugs, a recent controlled study found that risperidone compared to placebo significantly reduced suicidal ideation in patients with MDD; however the effects of risperidone augmentation were apparent at 2 weeks posttreatment.[21]

The slow onset of action of antidepressants has prompted considering the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for severely depressed patients, as a treatment modality for suicidal ideation.[22]

Comparing our results with the findings of DiazGranados et al.[23] we confirmed the rapid antisuicidal effect of ketamine, the longer follow-up period; use of HDRS-SI subscale in this study allowed us to obtain additional information regarding time of onset, course of response, and degree of improvement, enhancing the strength of this study. Compared to the previous study we found similar onset of decline in SSI scores. We detected robust improvement in HDRS-SI scores, at 40 minutes with more than 70% change over baseline. Decline in both SSI and HDRS-SI scores remained significant up to 230 minutes postinfusion.

While comparing our results with the findings of Zarate et al.,[24] we corroborated the rapid antidepressant effect of ketamine. Compared with the previous study, our study detected an earlier onset of antidepressant response (80 minutes vs. 110 minutes), significant change in HDRS scores from baseline sustained for a shorter period.

Early preclinical studies postulated that ketamine's mechanism of action is initially mediated by NMDA antagonism but subsequently involves enhanced throughput of a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA). Recent studies suggest that ketamine probably acts by disinhibiting GABAergic inputs and thereby accentuating the firing rate of glutamatergic neurons, increasing the presynaptic release of glutamate, and resulting in increased extracellular levels of glutamate. This increased glutamate release preferentially favors AMPA receptors over NMDA receptors, because the latter are blocked by ketamine; the net effect of ketamine's antidepressant effect on a cellular level is thus an enhanced glutamatergic throughput of AMPA relative to NMDA.[25,26]

The real strength of this study rests in documenting the rapid, albeit short-lived, antidepressant and antisuicidal effect of ketamine in an Indian subpopulation with TRD, highlighting the aspect that improvement associated with ketamine infusion reflects a lessening of core depressive symptomatology and is disconnected from ketamine-induced euphoria and psychotomimetic symptoms [Figure 4] and that ketamine exerts its effects remarkably, considering its short half-life,[27] which might be useful clinically.

Our preliminary results need to be interpreted with caution given the small group size and the open-label nature of the study. Nevertheless, the significant and often quick response seen in some individuals who were refractory to many traditional antidepressants suggests that directly modulating the glutamatergic system may ultimately be effective in treating suicidal ideation. It is important to note that the improvement in suicidal ideation observed here occurred in the context of severe depression.

However, several limitations do exist and the results of this preliminary study should be interpreted cautiously; as the sample size was small, there was no placebo arm. The results might not be generalized to all populations as all patients do not respond to ketamine the same way. Blood levels of ketamine or its metabolites were not collected; differences in drug metabolism could have contributed in part to the findings. Whether ketamine rapidly reduces suicidal ideation in patients with a diagnosis other than MDD is unknown.

The speedy onset and robust improvement we observed suggests that IV ketamine, administered in the hospital setting with appropriate safety monitoring, may offer an attractive intervention for acutely suicidal depressed patients. These findings highlight the possibility of quick intervention strategies to prevent suicidal behavior, which could have enormous public health impact. However further in-depth relapse prevention strategies[28] or newer therapeutic protocols for sustained antisuicidal effects need to be explored.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Claassen CA, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Husain MM, Zisook S, Young E, et al. Clinical differences among depressed patients with and without a history of suicide attempts: Findings from the STAR*D trial. J Affect Disord. 2007;97:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deisenhammer EA, Ing CM, Strauss R, Kemmler G, Hinterhuber H, Weiss EM. The duration of the suicidal process: How much time is left for intervention between consideration and accomplishment of a suicide attempt? J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt IM, Kapur N, Webb R, Robinson J, Burns J, Shaw J, et al. Suicide in recently discharged psychiatric patients: A case-control study. Psychol Med. 2009;39:443–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janofsky JS. Reducing inpatient suicide risk: Using human factors analysis to improve observation practices. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills PD, DeRosier JM, Ballot BA, Shepherd M, Bagian JP. Inpatient suicide and suicide attempts in Veterans Affairs hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:482–8. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeager KR Y, Saveanu R, Robers AR, et al. Measured response to identified suicide risk and violence: what you need to know about psychiatric patient safety. Brief Treat Crisis Interven. 2005;5:121–141. (text book) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jick H, Kaye JA, Jick SS. Antidepressants and the risk of suicidal behaviors. JAMA. 2004;292:338–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellner CH, Fink M, Knapp R, Petrides G, Husain M, Rummans T, et al. Relief of expressed suicidal intent by ECT: A consortium for research in ECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:977–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szanto K, Mulsant BH, Houck P, Dew MA, Reynolds CF., 3rd Occurrence and course of suicidality during short-term treatment of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:610–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Davis P, Pompili M, Goodwin FK, Hennen J. Decreased risk of suicides and suicide attempts during long-term lithium treatment: A meta-analytic review. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:625–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzzetta F, Tondo L, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ. Lithium treatment reduces suicide risk in recurrent major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:380–3. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, Altamura AC, Anand R, Bertoldi A, et al. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:82–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathew SJ, Murrough JW, Aan Het Rot M, Collins KA, Reich DL, Charney DS. Riluzole for relapse prevention following intravenous ketamine in treatment-resistant depression: A pilot randomized, placebo-controlled continuation trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:71–82. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Antisuicide properties of psychotropic drugs: A critical review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2004;12:14–41. doi: 10.1080/10673220490425924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sackeim HA. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 16):10–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams AR. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV TR Axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The scale for suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holi MM, Pelkonen M, Karlsson L, Kiviruusu O, Ruuttu T, Heilä H, et al. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI) in adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeves H, Batra S, May RS, Zhang R, Dahl DC, Li X. Efficacy of risperidone augmentation to antidepressants in the management of suicidality in major depressive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1228–336. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel M, Patel S, Hardy DW, Benzies BJ, Tare V. Should electroconvulsive therapy be an early consideration for suicidal patients? J ECT. 2006;22:113–5. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiazGranados N, Ibrahim LA, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Henter ID, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. Rapid resolution of suicidal ideation after a single infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1605–11. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05327blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:856–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moghaddam B, Adams B, Verma A, Daly D. Activation of glutamatergic neurotransmission by ketamine: A novel step in the pathway from NMDA receptor blockade to dopaminergic and cognitive disruptions associated with the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2921–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maeng S, Zarate CA, Jr, Du J, Schloesser RJ, McCammon J, Chen G, et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: Role of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:349–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White PF, Schuttler J, Shafer A, Stanski DR, Horai Y, Trevor AJ. Comparative pharmacology of the ketamine isomers: Studies in volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 1985;57:197–203. doi: 10.1093/bja/57.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao TS, Andrade C. Innovative approaches to treatment- refractory depression: The ketamine story. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:97–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.64573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]