To The Editor

CFS a complex disorder characterized by unexplained severe fatigue for over 6 months with a broad range of additional symptoms involving the nervous, endocrine and immune systems, and an estimated prevalence of 1%1. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are prescribed off label for a number of painful diseases that are often comorbid, such as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), fibromyalgia, interstitial cystitis, and irritable bowel syndrome, the symptoms of which are worsened by stress2. However, there is no known mechanism to explain the apparent beneficial action of TCAs3.

Mast cells and their mediators have been implicated in inflammatory diseases4, including CFS5. Mast cells are located perivascularly in close proximity to neurons in the thalamus and hypothalamus, especially the median eminence6, where they are juxtaposed to corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)-positive nerve processes7. CRH activates mast cells to release vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)8, which could participate in neurogenic inflammation and contribute to the pathogenesis of CFS. Such mediators may be released locally in the brain or may cross the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), which can be disrupted by stress, subsequent to mast cell activation9. Given the above, we hypothesized that TCAs may be helpful through inhibition of mast cell release of pro-inflammatory mediators.

LAD2 human mast cells10 were cultured mast cells were pre-incubated for 10 min with each one of the following drugs: the tricyclic amitriptyline (AMI), the specific serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram (CIT), the dopamine and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake inhibitor (DNRI) bupropion (BUP), the specific NE reuptake inhibitor tomoxetine (TOM), the tricyclic phenothiazine prochlorperazine (PRO), purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), before stimulation for 24 hrs with SP (10 μM from Sigma).

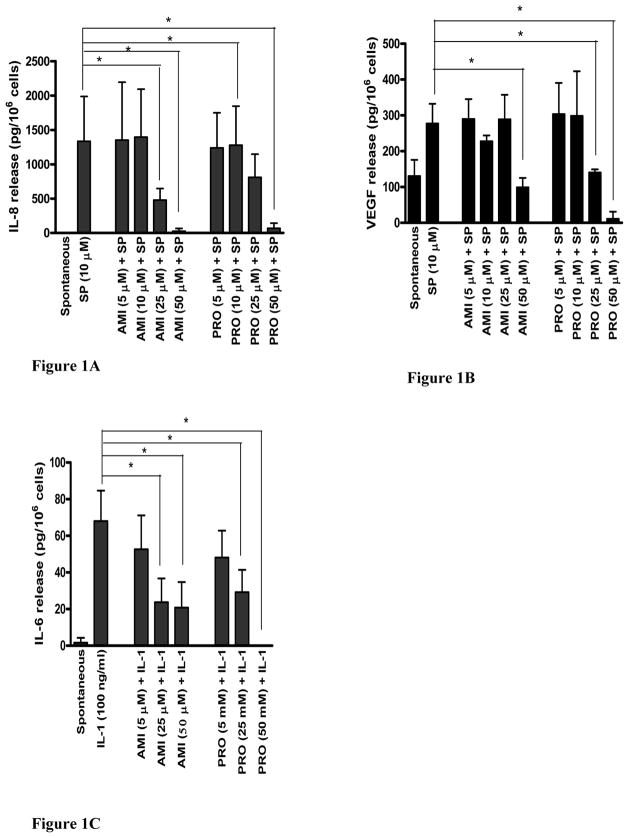

AMI (25 and 50 μM) inhibited (Fig. 1A) IL-8 release by 64.2% (from 1334 ±267 to 478±69 pg/μl) and 98.1% (from 1334 ±267 to 25 ±16 pg/μl, N=3, n=6, p<0.05), respectively. PRO (50 μM) inhibited SP-induced IL-8 release by 95% (Fig. 1A). AMI (50 μM) also significantly inhibited SP (10 μM)-induced VEGF release (Fig. 2B) by 64.3% (from 277.4 ±54.7 to 98.9 ±26.5 pg/μl, N=3, n=6, p<0.05). PRO (50 μM) inhibited VEGF release by 96% (Fig. 1B). All other antidepressants had no effect on either IL-8 or VEGF release; cell viability was unaffected (not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of AMI and PRO on SP-induced (A) IL-8 and (B) VEGF release from LAD2 cells, as well as on (C) IL-1-induced IL-6 release from HMC-1 cells. Drugs were added to the cells at the concentrations indicated for 10 min prior to stimulation with SP (10 μM) or prior to stimulation with IL-1 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hr (N=3, n=6). AMI, BUP, CIT, TOM, PRO and SP were dissolved in 0.1% acetic acid and stored at −20° C. All drugs were thawed at room temperature the day of the experiment. The final concentration of the vehicles did not have an effect (data not shown). The cell viability for all experiments following incubation with the highest concentrations of the drugs tested for 24 hr was >90% by Trypan blue exclusion. LAD2 leukemic mast cells were cultured using StemPro-34 serum free media (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 ng/ml recombinant human stem cell factor (rhSCF, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. HMC-1 leukemic mast cells were cultured using IMDM (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 5 ml of 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 50 ml FCS, and 52 μl α-thioglycol). The cultures were used during their logarithmic growth. IL-6, IL-8 and VEGF release in cell-free supernatants were measured by ELISA (R&D Systems). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (picograms per 106 cells) of “net” release (spontaneous release was ubtracted before inhibition calculations were performed) from three or more experiments (N), each performed in triplicate (n). Results were analyzed with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test. Statistical significance was set at p< 0.05.

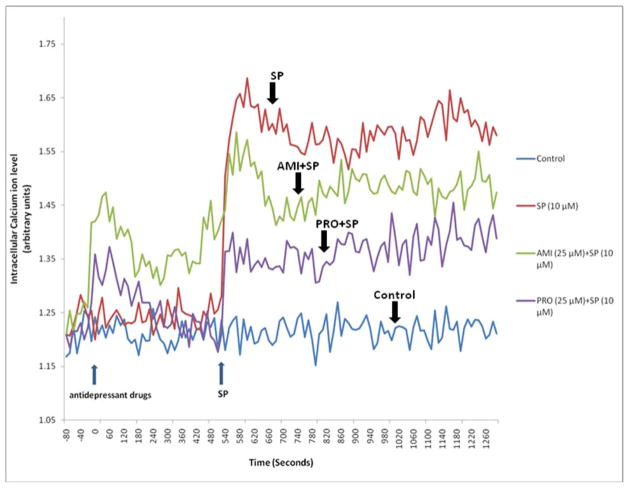

FIGURE 2.

Effect of AMI and PRO on LAD2 intracellular calcium ion levels. LAD2 cells were pre-incubated with the calcium indicator FURA2 AM (Invitrogen) for 20 min, washed and then incubated with either drug (25 μM) for 10 min prior to addition of SP(10 μM) during which time continuous recordings were obtained at 37°C. Fluorescence was recorded using MDC FlexStation II (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA) at excitation wavelength of 340 nm/380 nm and emission wavelength of 510 nm. The graph is a representative one of three similar experiments.

In view of the fact that only AMI had any inhibitory effect, we investigated the effect of AMI on mast cell activation by an inflammatory trigger.LAD2 cells do not synthesize IL-6, while HMC-1 cells response to IL-1 by secreting only IL-6. HMC-1 cells (1 × 105 cells/200 μl) were pre-incubated with AMI (5, 25 and 50 μM) for 10 min before stimulation with IL-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 hrs (Fig. 1C). AMI (25 and 50 μM) significantly inhibited IL-6 release by 65.1% (from 68.0 ±16.6 to 23.7 ±13.0 pg/μl) and 69.4% (from 68.0 ±16.6 to 20.8 ±13.9 pg/μl), respectively (N=3, n=6, p<0.05). PRO (50 μM) inhibited VEGF release by 100% (Fig. 1C).

In an effort to understand the mechanism of the inhibitory action of AMI and PRO on LAD2 secretion, we investigated their effect on intracellular calcium ions. SP rapidly (2 min) increased intracellular calcium ion levels that decreased by 20 min (Fig. 2). Both AMI and PRO decreased the SP-induced cytosolic calcium increase (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

Our findings may be supported by the results of a meta analysis of fibromyalgia clinical trials that concluded that only TCAs had a large effect on pain reduction, while SSRIs had a small effect11; it should be noted, however, that serum antidepressant levels had not been measured to assess patient compliance, and no study controlled for the concurrent consumption of analgesic medications. It is interesting that the tricyclic phenothiazine prochlorperazine, commonly used as an antiemetic, was also a potent inhibitor of human mast cell activation. The concentration of AMI and PRO shown here to effectively inhibit mast cell secretion is about 10 times higher than what might be expected from the maximal daily dose (e.g. assuming one compartment model for an 80 kg subject, the AMI max dose of 150 mg would yield a serum level of 6 μM). However, brain mast cells may be more susceptible to the action of AMI than the human cultured LAD2 leukemic mast cells.

The mechanism through which TCAs can inhibit mast cell secretion is still not clear. Here we show that AMI and PRO can decrease intracellular calcium ion levels. We had previously shown that the inhibitory effect of AMI on rat peritoneal mast cells could be overcome by calcium ions12. Other authors had reported that AMI and desipramine (1 μM) partially prevented intracellular calcium increase due to N-methyl-D-aspartate in cerebellar granule neurons13. The tricyclic phenothiazine chlorpromazine could inhibit the calcium flux due to compound 48/80 in rat peritoneal mast cells14, and its inhibitory effect could be overcome by the presence of extracellular calcium15.

Mast cells are important for allergic reactions and in immunity16, but also in inflammatory conditions4. In addition to allergic triggers, a number of neuropeptides can also stimulate mast cell secretion including SP17. Mast cells secrete numerous vasodilatory and proinflammatory mediators, including IL-6, IL-8 and VEGF. IL-8 was shown to be elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of CFS patients18. IL-6 and IL-8 were elevated in the serum of CFS patients with symptom flare following moderate exercise19, while another study using Multiplex microbead arrays reported high plasma IL-6, low IL-8, and no change in TNF levels in female CFS subjects at rest as compared to controls20. However, both the source and the methodologies differed between these two studies.

The ability of AMI, but not other antidepressants, to inhibit human mast cell release of pro-inflammatory cytokines may be relevant to their apparent benefit in CFS. PRO may also be useful.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by NIH grant R21AR47652 to TCT. AC was a PREP (Post-Baccalaureate Research Experience Program) student supported by NIH grant R25 GM066567. We thank Amgen, Inc. for their generous gift of rhSCF, Drs. D. Metcalfe and A. S. Kirshenbaum (NIH, Bethesda, MD) for providing the LAD2 cells, and Dr. Joseph Butterfield (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) for providing the HMC-1 cells.

Abbreviations

- AMI

Amitriptyline

- BUP

bupropion

- CFS

chronic fatigue syndrome

- 5-HT

5-hydroxy tryptamine

- CIT

citalopram

- DNRI

dopamine-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

- FM

fibromyalgia

- PRO

prochlorperazine

- SCF

recombinant human stem cell factor

- SNRI

serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

- SP

subatance P

- SSRI

serotonin specific reuptake inhibitor

- TOM

tomoxetine

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Avellaneda FA, Perz MA, Izquierdo MM, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;(Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aaron LA, Buchwald D. Chronic diffuse musculoskeletal pain, fibromyalgia and co-morbid unexplained clinical conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17(4):563–74. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(03)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pae CU, Marks DM, Patkar AA, et al. Pharmacological treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome: focusing on the role of antidepressants. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(10):1561–70. doi: 10.1517/14656560902988510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theoharides TC, Cochrane DE. Critical role of mast cells in inflammatory diseases and the effect of acute stress. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;146:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theoharides TC, Papaliodis D, Tagen M, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome, mast cells, and tricyclic antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(6):515–20. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000193483.89260.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollard H, Bischoff S, Llorens-Cortes C, et al. Histidine decarboxylase and histamine in discrete nuclei of rat hypothalamus and the evidence for mast cells in the median eminence. Brain Res. 1976;118:509–13. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rozniecki JJ, Dimitriadou V, Lambracht-Hall M, et al. Morphological and functional demonstration of rat dura mast cell-neuron interactions in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 1999;849:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theoharides TC, Donelan JM, Papadopoulou N, et al. Mast cells as targets of corticotropin-releasing factor and related peptides. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:563–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esposito P, Chandler N, Kandere K, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and brain mast cells regulate blood-brain-barrier permeability induced by acute stress. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2002;303:1061–1066. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.038497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirshenbaum AS, Akin C, Wu Y, et al. Characterization of novel stem cell factor responsive human mast cell lines LAD 1 and 2 established from a patient with mast cell sarcoma/leukemia; activation following aggregation of FcepsilonRI or FcgammaRI. Leuk Res. 2003;27:677–82. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauser W, Bernardy K, Uceyler N, et al. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(2):198–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theoharides TC, Bondy PK, Tsakalos ND, et al. Differential release of serotonin and histamine from mast cells. Nature. 1982;297:229–31. doi: 10.1038/297229a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai Z, McCaslin PP. Amitriptyline, desipramine, cyproheptadine and carbamazepine, in concentrations used therapeutically, reduce kainate- and N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced intracellular Ca2+ levels in neuronal culture. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;219(1):53–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90579-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson HG, Miller MD. Inhibition of histamine release and ionophore-induced calcium flux in rat mast cells by lidocaine and chlorpromazine. Agents Actions. 1979;9(3):239–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01966694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peachell PT, Pearce FL. Divalent cation dependence of the inhibition by phenothiazines of mediator release from mast cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;97(2):547–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galli SJ, Kalesnikoff J, Grimbaldeston MA, et al. Mast cells as “tunable” effector and immunoregulatory cells: recent advances. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:749–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theoharides TC, Zang B, Kempuraj D, et al. IL-33 augments substance P-induced VEGF secretion from human mast cells and is increased in psoriatic skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4448–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000803107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Natelson BH, Weaver SA, Tseng CL, et al. Spinal fluid abnormalities in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(1):52–5. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.1.52-55.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White AT, Light AR, Hughen RW, et al. Severity of symptom flare after moderate exercise is linked to cytokine activity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychopsysiology. 2010;47:615–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher MA, Zeng XR, Barnes Z, et al. Plasma cytokines in women with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Transl Med. 2009;7:96. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-96. (on line) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]